Abstract

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is a worldwide infectious disease caused by flagellate protozoa of the genus Leishmania. In America, the species most commonly responsible for CL are L. mexicana and L. brasiliensis. Usually, in America, it is transmitted by sand flies mainly of the genus Lutzomyia and Psychodopygus. CL most commonly affects exposed areas and is characterized by an erythematous infiltrated and ulcerated papular or nodular lesion. We report a 28-year-old male, with a 6-month history and a previous trip to the forest in the south of Mexico. He presented with an asymptomatic erythematous plaque on his scalp, with slow and progressive nodular lesions with central crusted ulceration, with a raised and well-defined border. On videodermoscopy, we observed erythematous gummy lesions, yellowish scabs, and white star, dotted, hairpin, and glomerular patterns of vessels.

Keywords: Videodermoscopy, Scalp, Cutaneous leishmaniasis

Established Facts

• Leishmaniasis on the scalp has rarely been reported.

Novel Insights

• This is the second published case report of leishmaniasis on the scalp worldwide and, to our knowledge, the dermoscopic features have not been previously reported.

Introduction

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is an infectious disease caused by flagellate protozoa of the genus Leishmania. In the new world, the species responsible for CL are usually L. mexicana and L. brasiliensis [1, 2]. In America, usually vectors such as Lutzomyia and Psychodopygus transmit the infection [3, 4]. CL has a worldwide distribution, occurring predominantly in Mexico, Central and South America, the Mediterranean area, Asia, and Africa [1, 3]. The most commonly affected areas are the exposed parts of the body, and the initial lesion is an erythematous infiltrated papule or nodule and later on develops a central ulcer and crusting [1].

Dermoscopy is a noninvasive diagnostic technique that facilitates the in vivo observation of the skin. It can be used for diagnoses of various skin diseases, especially pigmented and nonpigmented tumors as well as inflammatory, parasitic, and infectious diseases [1, 5].

CL features are generalized erythema (most common), yellow tears, hyperkeratosis, central erosion, ulceration, a white starburst-like pattern, and other types of vascular structures [1, 5, 6].

Case Report

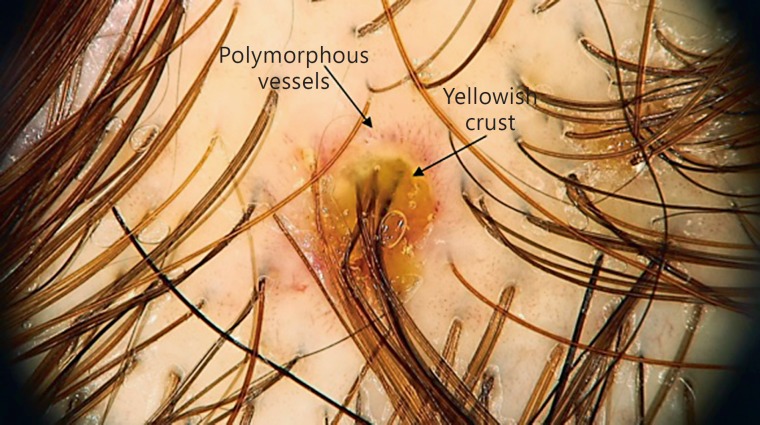

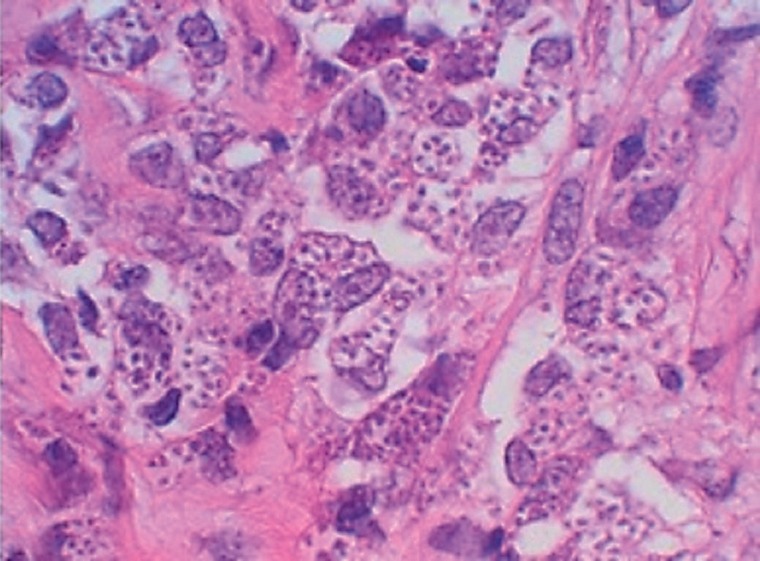

We present the case of a 28-year-old male with a 6-month history of an asymptomatic erythematous plaque on his scalp, with slow and progressive nodules with central ulceration and yellowish crusting, with raised and well-defined borders (Fig. 1a). Videodermoscopy showed erythema and a yellowish crust surrounded by polymorphous vessels (Fig. 2). Amastigotes were observed on Giemsa stain (impronta), and a histopathological study showed hyperkeratosis, ulceration with fibrin and cellular debris, irregular acanthosis, areas of spongiosis and exocytosis of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and some polymorphonuclear cells. In the superficial, middle, and deep dermis, a dense inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, polymorphonuclear foci, and histiocytes was observed, some of them with numerous inclusion bodies, these structures are also extracellular. Dilation and congestion of blood vessels and countless leishmania bodies were observed (Fig. 3). Initial treatment included intralesional meglumine antimoniate, 3 times (every 3 weeks) and, later on, oral itraconazole 200 mg daily during 2 months with a good response (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

a Macroscopic view of the ulcerated nodular lesion. b Patient remission.

Fig. 2.

Microdermoscopic view (×50) of the ulcerated nodular lesion.

Fig. 3.

Microscopic view of the histopathological lesion. ×40.

Discussion

CL is an infectious diseases caused by flagellate protozoa of the genus Leishmania. It is mainly caused by L. major, L. infantum, L. tropica, L. aethiopica, and L. donovani infantum; however, in the new world, the species responsible for CL are usually L. mexicana and L. brasiliensis [1, 2].

The clinical diagnosis is confirmed with a simple test finding the microscopic amastigotes in Giemsa-stained smears obtained from the infected skin, lymph node, bone marrow, spleen, or spinal-fluid as well as by the growth of promastigotes in Novy-MacNeal-Nicolle medium in up to 40% of cases. Another diagnostic test is the demonstration of leishmanial DNA by PCR [3].

Histopathological findings are consistent with a tuberculoid granuloma with lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma and epithelioid cells [2]. Dermoscopy may reduce the need for more invasive and expensive diagnostic tests for CL [1, 5].

In a study conducted in Iran by Taheri et al. [1], the most common dermoscopic finding of CL was generalized erythema, followed by a white starburst-like pattern (parakeratotic hyperkeratosis located around the lesions), central ulcers, yellowish hues and yellow teardrop-like structure, and hyperkeratosis. The most common vascular feature was dotted, followed by hairpin-like, linear irregular, comma-shaped and glomerular-like pattern of vessels with arborizing telangiectasia, and corkscrew vessels [1].

In Turkey, Ayhan et al. [5] found that the vascular structures observed on dermoscopy were most commonly polymorphic vessels, followed by hairpin-like and arborizing vessels. The most common nonvascular structure was erythema, followed by crusting, erosion/ulceration, and teardrop-like structures. They concluded that teardrop-like structures may be specific to leishmaniasis localized on the face and neck [5].

In our case, we observed similar clinical and dermoscopic features on the scalp, where the characteristic lesions had a yellowish crust surrounded by polymorphous vessels; we did not observe the typical teardrop-like structures and white star pattern.

Our findings probably differ from those described in the literature because our study included only patients with leishmaniasis on the face, neck, and extremities, and none with lesions on the scalp.

The clinical differential diagnosis of this scalp localization of CL is kerion celsi. Clinical features of kerion celsi range from mild scaling with little hair loss to large inflammatory and pustular plaques with extensive alopecia. In our case, we found nodules with central ulceration and yellowish crusting, with raised and well-defined borders, without alopecia [7]. In addition, the most common dermoscopic findings of kerion celsi are perifollicular scaling and broken hairs. These differ from the dermoscopic findings of CL [8].

Treatment of CL includes topical agents (cryotherapy, sublesional application of the 5-valent antimonial preparation meglumine antimoniate [Glucantim, amp. 5 mL], ointments containing 15% paromomycin and 10% urea, a local thermal therapy at temperatures of 40–42°C, and systemic agents [pentavalent antimonial drugs and antibiotics such as sodium stibogluconate and meglumine antimoniate, pentamidine, paromomycin, miltefosine]) [1, 6, 9]. In cases caused by L. mexicana, there is a good response with itraconazole 200–400 mg per day for 1–2 months [10].

We treated our patient with intralesional meglumine antimoniate on 3 occasions and oral itraconazole 200 mg for 2 months with an excellent response, since the lesions were completely healed.

This is the second case described in the literature of CL of the scalp and the first one describing trichoscopic findings.

Statement of Ethics

This study did not require approval by the institute's committee on human research. The patient gave consent for the use of anonymized photographs for research purposes.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Taheri AR, Pishgooei N, Maleki M, Goyonlo VM, Kiafar B, Banihashemi M, et al. Tropical medicine rounds: Dermoscopic features of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Int J Dermatol. 2013:1361–1366. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marovt M, Kokol R, Stanimirović A, Miljković J. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: a case report. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2010;19:41–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neupane S, Sharma P, Kumar A, Paudel U, Pokhrel DB. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: report of rare cases in Nepal. Nepal Med Coll J. 2008;10:64–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cembrero-saralegui H, Pérez MM, Imbernón-moya A. Dermoscopy of acute cutaneous leishmaniasis. Med Clin (Barc) 2017;148:e29. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ayhan E, Ucmak D, Baykara SN, Akkurt ZM, Arica M. Clinical and dermoscopic evaluation of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:193–201. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dobrev HP, Nocheva DG, Vuchev DI, Grancharova RD. Cutaneous leishmaniasis - dermoscopic findings and cryotherapy. Folia Med (Plovdiv) 2015;57:65–68. doi: 10.1515/folmed-2015-0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hay RJ. Tinea capitis: current status. Mycopathologia. 2017;182:87–93. doi: 10.1007/s11046-016-0058-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brasileiro A, Campos S, Cabete J, Galhardas C, Lencastre A, Serrao V. Trichoscopy as an additional tool for the differential diagnosis of tinea capitis: a prospective clinical study. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:208–209. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antinori S, Gianelli E, Calattini S, Longhi E, Gramiccia M, Corbellino M. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: an increasing threat for travellers. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005;11:343–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.01046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torres-Guerrero E, Quintanilla-Cedillo MR, Ruiz-Esmenjaud J, Arenas R. Leishmaniasis: a review. F1000Res. 2017;6:750. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.11120.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]