Abstract

Alopecia areata (AA)-like disease is characterized by multifocal patchy hair loss in humans, rodents, dogs, and horses. Remarkable similarities between human and nonhuman AA cases have been reported in terms of clinical presentation, histology, and immune mechanisms of the disease. Canine AA-like lesions most often consist of well-demarcated alopecic patches, frequently but not only involving the face and the head, which extend to the ear pinnae and legs. In some cases, hair loss can have a more generalized distribution. As in humans, hair regrowth is most commonly spontaneous in canine AA-like disease and the resistant cases usually respond to glucocorticoids or cyclosporine treatment. Diagnosis of AA in veterinary medicine relies on presentation, histopathology, and immunohistochemistry and on regrowth following therapy. This case report describes the first dermoscopic evaluation of AA-like disease in a dog with a clinical presentation of symmetrical hair loss.

Keywords: Alopecia areata, Dog, Dermoscopy, Immune-mediated bulbitis, Cyclosporine

Established Facts

• Remarkable similarities between human and canine alopecia areata (AA) have been reported in terms of clinical presentation, histology, and immune mechanisms of the disease.

• Dermoscopic features for canine AA-like are not reported.

Novel Insights

• The main dermoscopic features observed in this case of canine AA are plugging of the follicular infundibulum with a yellow-brown material (yellow-brown dots), few broken hairs and thinning short regrowing hairs arising individually from follicular ostia. No tapering hair or coudability hair was observed.

Introduction

Alopecia areata (AA)-like disease is an occasional cause of alopecia in dogs as well as in other mammalians. Most cases in veterinary medicine have been described in horses. AA-like disease is considered rare; however, its prevalence might be higher than currently perceived because minor forms and cases undergoing spontaneous regression may go underdiagnosed in veterinary medicine [1].

Comparative analysis of AA-like hair disorders reveals remarkable similarities between human and other species in terms of clinical presentation, microscopical features, and immune reactions involved in disease pathogenesis [2]. AA-like disease has been described in several canine breeds and in mongrels, but Dachshund seems a predisposed breed from which all the reported cases were taken. Canine AA-like lesions consist of well-demarcated alopecic patches frequently involving the face and head and extending to the ear pinnae and legs [1]. In some cases, hair loss can have a more generalized distribution and two dogs developing diffuse alopecia also including vibrissae and eyelashes have recently been reported [3, 4]. In dogs with variable hair coat color, hair loss usually occurs first in dark brown or black areas and in a minority of cases the growth of white hair may precede the first alopecic lesions [1].

The usefulness of trichoscopy (hair and scalp dermoscopy) has been reported for hair loss diseases in human dermatology. In noncicatricial alopecias such as AA and androgenetic alopecia, suggestive trichoscopic findings are represented by specific hair shaft and follicular opening abnormalities. For AA trichoscopic findings of black dots, tapering hairs, broken hairs, yellow dots, and clustered short vellus hairs are reported as useful indicators of this condition [5].

This case report describes the dermoscopic and histopathological features of AA-like disease in a dog with a clinical presentation of symmetrical hair loss.

Case Report

An 11-year-old intact female Dachshund dog presented with a 4-month history of progressive alopecia. Hair loss began on the ventral neck and progressed to the chest, abdomen, head, and proximal limbs. At the time of presentation, general physical examination was unremarkable. Dermatological examination revealed symmetrical alopecia of temporal, periocular and postauricular regions of the head, and alopecia was also present in proximal limbs and the ventral aspect of the trunk (Fig. 1). The skin was hyperpigmented in the alopecic areas. Differential diagnoses included endocrine diseases, canine pattern alopecia, and immune-mediated folliculitis.

Fig. 1.

Clinical aspect of alopecia areata in a Dachund dog: symmetrical alopecia of the head, neck, and ventral aspect of the trunk.

Complete blood count, routine clinical biochemistry, and urine cortisol/creatinine ratio were within normal laboratory reference ranges.

Dermoscopy of skin lesions was performed without immersion fluid at 10-fold magnification with a nonpolarized dermoscope (Heine Delta 20, Heine Optotechnik GmbH & Co., Herrsching, Germany) connected to a digital camera (Nikon D3100, Europe BV).

The main dermoscopic features observed in alopecic areas were plugging of the follicular infundibulum with a yellow-brown material (yellow-brown dots) (Fig. 2c, d, white arrows), few broken hairs (Fig. 2d, black arrows), and thinning short regrowing hairs arising individually from follicular ostia (Fig. 2c, black arrows). Honeycomb-like pigmented network was also detected on the bold interfollicular skin that was exposed to the sun (Fig. 2c, red arrows). No tapering hair or coudability hair was observed.

Fig. 2.

Dermoscopic features of alopecic areas on the head (a, c) and on the trunk (b, d) at 10- (a, b) and 20-fold (c, d) magnification. Follicular infundibula mostly devoid of hair and containing yellow-brown material (yellow-brown dots) are the most common feature on both sites (c, d, white arrows). Also note thinning short regrowing hairs arising individually from follicular ostia (c, black arrows), broken hairs (d, black arrows), and honeycomb-like pigmented network on the interfollicular skin (c, red arrows).

Multiple skin biopsies were taken from the head, trunk, and limbs in the same areas evaluated by dermoscopy. Tissue samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, routinely processed, cut in 5-μm-thin sections, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For immunohistochemistry, paraffin sections (4–6 μm) were mounted onto poly-L-lysine-coated slides, deparaffinized and hydrated through graded ethanol solutions. Endogenous peroxidase was quenched with hydrogen peroxide (0.3%) and sodium azide (0.1%) in Tris buffer (0.1-M solution, pH 7.5) for 30 min. Following heat-induced antigen retrieval for 4 min, primary antibodies anti-CD3 epsilon chain (CD3–12, rabbit polyclonal, 1:10, Serotec, Oxford, UK) and anti-CD79a (Hm57, mouse monoclonal, 1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA) were applied. Secondary detection was performed with the avidin-biotin enzyme complex (Vectastain®, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 30 min and developed with the peroxidase amino-9-ethyl-carbazole substrate kit (Dako®, Glostrup, Denmark). Smears were counterstained with Mayer hematoxylin for 3 min and coverslipped with an aqueous mounting medium (Glycerol, Sigma-Aldrich®, St. Louis, MO, USA). Negative controls consisted of substitution of specific antibodies with an isotype-matched, irrelevant monoclonal antibody or omission of the primary antibody. Sections of canine-reactive peripheral submandibular lymph node were used as positive controls.

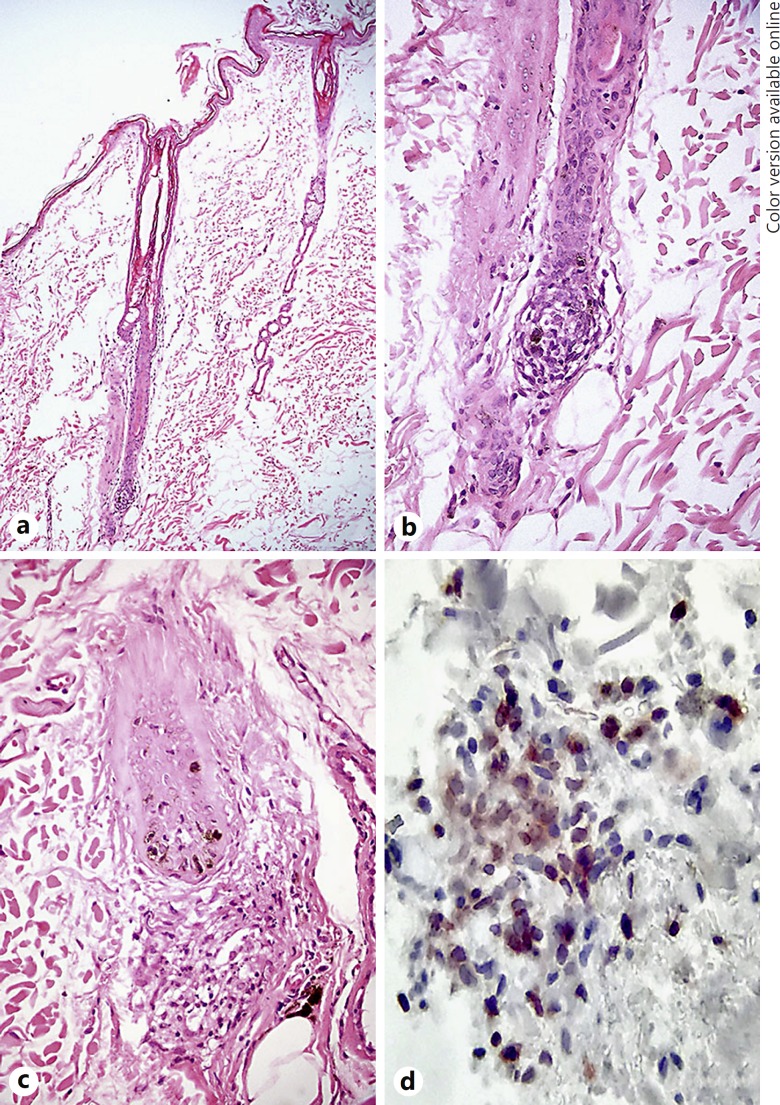

Routine microscopic examination showed similar lesions in all samples. Moderate, diffuse infundibular keratosis and diffuse follicular atrophy, dystrophy, and miniaturization of growing hair follicles were observed (Fig. 3a). In the deep dermis, rare residual small anagen bulbs were infiltrated by small mature lymphocytes and occasional foamy reactive macrophages (Fig. 3b). In the peribulbar dermis, mild pigmentary incontinence, fibrosis, and occasional histiocytes were also present. Occasional bulbar keratinocyte pyknosis and nuclear fragmentation consistent with apoptosis were also present (Fig. 3c). Isthmic and infundibular areas were unaffected. Immunohistochemistry demonstrated a prevalence of CD3-positive bulbar infiltrating small mature T lymphocytes (Fig. 3d).

Fig. 3.

Histologic features. a Haired skin, dog: severe hair follicle atrophy is visible. Only one hair follicular unit with a bulb in deep location is visible. Loss of the normal arrangement in compound hair shafts is also evident. HE. ×4 magnification. b Haired skin, dog: the hair bulb is characterized by intracellular edema of keratinocytes and mild infiltration of hair bulb and dermal papilla by small mature lymphocytes and abnormal distribution (likely reduction) of melanocytes. HE. ×200 magnification. c Haired skin, dog: atrophic hair follicle with thickened fibrous sheath and underlying area of focal histiocytic and lymphocytic inflammation with pigmentary incontinence corresponding to the pre-existing hair bulb area. HE. ×200 magnification. d Haired skin, dog: numerous CD3-positive mature and reactive T cells in a residual hair bulbar area. Anti-CD3, carbazole chromogen, Mayer hematoxylin counterstain. ×400 magnification.

Morphological and immunohistochemical characteristics confirmed the diagnosis of follicular atrophy with T cell bulbitis consistent with canine AA-like disease. Some microscopic features of hair follicle miniaturization suggested the concurrent presence of a pattern alopecia.

As no spontaneous hair regrowth was observed in 4 months, the dog was treated with oral cyclosporine 5 mg/kg once daily (Atoplus, Elanco Italia SpA, Sesto Fiorentino, Florence, Italy) for 45 days. The drug was discontinued because no improvement was observed. One month later, the hair regrew only on the head (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Follow-up after 6 months: hair regrowth on the dog's head.

Discussion

Mammalian domesticated species may develop similar conditions as described in humans and often function as good spontaneous models of the human disease counterpart. Approximately 400 inherited disorders have been characterized in domesticated dogs, most of which are relevant and spontaneous models of human diseases. AA-like disease is characterized by hair loss in people, rodents, dogs, and horses and share clinical and pathological features as wells as the same pathogenesis and, treatment response. The fact that antibodies to anagen hair follicles in rats, mice, dogs, and horses are similar and cross-react with tissues from different species is likely to reflect a high level of antigen conservation in the hair follicles of many mammalian species [2].

Paralleling human disease, canine AA-like is theorized to have a T-cell-mediated autoimmune origin. Even if the paucity of reported cases and the poor characterization of natural diseases in dogs prevent the assessment of their scientific value, there has also been some progress in the evaluation of the immune status of AA in dogs [6, 7, 8]. Indeed, a study from Tobin et al. [7] assessed AA-like hair loss in 25 client-owned dogs using AA-associated clinical, histological and immunological criteria [9, 10]. In this study, skin biopsy specimens revealed a predominantly T lymphocyte infiltration in and around hair follicles and hair bulbs. T cells infiltrating hair bulb epithelium itself were mainly CD8+, while CD4+ T cells predominated in the peribulbar T cell infiltrate. Furthermore, canine AA-like disease has been associated with deposition of both autoantibodies and complement around hair follicles and with circulating antibodies (IgM and IgG) to hair follicle-specific antigens. These findings in AA-like-disease-affected dogs closely parallel those reported in people with AA suggesting that the canine species could represent a useful homologue for the study of this autoimmune disease [7].

As in humans, hair regrowth is most commonly spontaneous in canine AA-like disease. Indeed, in a large case study, 60% of dogs underwent spontaneous hair regrowth within months from initial diagnosis and the resistant cases went in remission with glucocorticoids or cyclosporine [7]. The dog of this report had only a partial delayed response to a short course of cyclosporine (1.5 months). Only one previous report has documented a similar clinical course in a cross-breed hunting dog [3]. Whether this outcome is due to the low level of cyclosporine in the skin of the treated dog or to a form of AA-like disease partially responsive to cyclosporine has not unfortunately been elucidated yet. A second option for this case could have been the coexistence of two conditions, AA-like disease and pattern alopecia, even if the latter occurs generally at a younger age.

The usefulness of trichoscopy has recently been suggested for the diagnosis of several conditions also in veterinary dermatology. Comma-like hairs have been described as the main characteristic features both in cats and dogs with dermatophytosis [11, 12, 13]. Canine pattern alopecia has been evaluated by dermoscopy in 20 short-haired dogs [14] and hair shaft thinning, scattered circle hairs, plugging of the follicular infundibulum with a yellow-brown material and honeycomb-like pattern pigmentation in sun-exposed areas were reported as the prevalent features.

Various dermoscopic features in human AA have been described and correlation between these features and disease severity and activity have been reported in a large study involving 300 patients affected by different stages and different subtypes of the diseases [5]. Yellow dots and short vellus hair are indicated as the most sensitive markers for AA diagnosis and black dots, tapering hairs and broken hairs as the most specific markers.

In our case, dermoscopic evaluation revealed plugging of the follicular infundibulum with a yellow-brown material (yellow-brown dots) and various hair shaft abnormalities were evidenced including broken hairs and thinning short regrowing hairs arising individually from follicular ostia. The observed features are indicative of a hair growth disturbance but are not specific. Yellow-brown dots that represent follicular infundibulum filled with sebum and keratin have also been reported in canine pattern alopecia [14], canine demodicosis [15] and also observed in some disorders of hair follicle cycling as hypercortisolism (unpublished data). Broken hairs are also a nonspecific finding and are also observed in friction alopecia (self-induced).

As in previous studies of canine pattern alopecia, only fair agreement was observed between dermoscopic and histopatological findings of follicular hyperkeratosis. This might have been influenced by histological processing that reduces the amount of sebum in the follicular infundibula. Thinning and short regrowing hair observed in dermoscopy in this case correlated with the miniaturization of growing follicles observed by histology. As previously reported in canine pattern alopecia, honeycomb-like hyperpigmentation pattern on bald skin were also observed in this dog. These features were more evident on the head than on the ventral trunk and neck. As demonstrated in people, these features result from solar exposure in thinning and completely balding areas and possibly in our case the head was as much involved as the most sun-exposed areas compared to the ventral skin.

Histopathology was consistent with AA-like disease characterized by infiltration of residual bulbs of anagen hairs by small mature lymphocytes. These findings closely resembled previous canine AA cases and paralleled microscopical features of human AA. The presence of reactive macrophages in bulbs and peribulbar dermis has also been reported in dogs and humans with AA. Also dendritic antigen-present cells have been observed and are considered relevant in disease emergence. The T cell phenotype of infiltrating small mature lymphocytes in this case was consistent with previous descriptions. Unfortunately, antibodies detecting CD8 and CD4 antigens in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded material are not available for dogs. In dogs, CD8 T cells represent the major component of the bulbar inflammation in AA-like disease [6] and apoptosis of bulbar keratinocytes has been demonstrated by in situ nicked DNA end-labelling [7]. Last but no least, autoantibodies reactive to multiple hair structures have been detected by indirect immunofluorescence in dogs and intense specific reactivity to trichohyalin protein has been demonstrated [7].

The additional microscopic finding of miniaturization could not be explained by the sole diagnosis of AA. This observation, in conjunction with trichoscopic findings and the partial response to cyclosporine, lead to the interpretation of two diseases developing concurrently such as AA and tardive onset acquired pattern alopecia (pattern baldness). Dachshunds are the most common and predisposed breed to pattern baldness development. This disease also resembles acquired human pattern baldness although androgen dependence has not been demonstrated in dogs. Clinical presentation is similar among humans and dogs and is represented by slow progressive thinning of hair coat with conversion of normal primary hairs to secondary hairs.

In conclusion, we describe the case of canine AA-like disease. Dermoscopic features observed in this case were considered not specific but clinical and histopathological features were consistent with a diagnosis of AA-like disease possibly associated with canine pattern alopecia. Treatment with oral cyclosporine was associated with partial clinical resolution.

Statement of Ethics

Informed owner consent was obtained before dermoscopy and biopsy procedures and all procedures were performed under good clinical practices in accordance with ethical guidance published in No. 289 of the national Gazzetta Ufficiale, December 10, 1996, pp. 47–53.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Tobin DJ. Alopecia areata. In: Mecklenburg L, Linek M, Tobin DJ, editors. Hair Loss Disorders in Domestic Animals. Ames: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. pp. 253–267. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McElwee KJ, Boggess D, Olivry T, Oliver RF, Whiting D, Tobin DJ, Bystryn JC, King LE, Jr, Sundeberg JP. Comparison of alopecia areata in human and non-human mammalian species. Pathobiology. 1998;66:90–107. doi: 10.1159/000028002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ginel PJ, Blanco B, Perez-Aranda M, Zafra R, Mozos E. Alopecia areata universalis in a dog. Vet Dermatol. 2015;26:379–383. doi: 10.1111/vde.12232. e87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Outerbridge CA, White SD, Affolter VK. Alopecia universalis in a dog with testicular neoplasia. Vet Dermatol. 2006;27:513–e139. doi: 10.1111/vde.12380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inui S, Nakajima T, Nakagawa K, Itami S. Clinical significance of dermatoscopy in alopecia areata: analysis of 300 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:688–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olivry T, Moore PF, Naydan DK, Puget BJ, Affolter VK, Kline AE. Antifollicular cell-mediated and humoral immunity in canine alopecia areata. Vet Dermatol. 1996;7:67–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3164.1996.tb00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tobin DJ, Gardner SH, Luther PB, Dunston SM, Lindsey NJ, Olivry T. A natural canine homologue of alopecia areata in humans. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:938–950. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2003.05610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tobin DJ, Olivry T. Spontaneous canine model of alopecia areata. In: Chan LS, editor. Animal Models of Human Inflammatory Skin Disease. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2004. pp. 469–482. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olsen E, Hordinsky M, McDonald-Hull S, Price V, Roberts J, Shapiro J, Stenn K. Alopecia areata investigational assessment guidelines. National Alopecia Areata Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40((2 Pt 1)):242–246. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70195-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olsen EA, Hordinsky MK, Price VH, Roberts JL, Shapiro J, Canfield D, Duvic M, King LE, Jr, McMichael AJ, Randall VR, Turner ML, Sperling L, Whiting DA, Norris D, National Alopecia Areata Foundation Alopecia areata investigational assessment guidelines-Part II. National Alopecia Areata Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:440–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scarampella F, Zanna G, Peano A, Fabbri E, Tosti A. Dermoscopic features in 12 cats with dermatophytosis and in 12 cats with self-induced alopecia due to other causes: an observational descriptive study. Vet Dermatol. 2015;26:282–e63. doi: 10.1111/vde.12212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong C, Angus J, Scarampella F, Neradilek M. Evaluation of dermoscopy in the diagnosis of naturally occurring dermatophytosis in cats. Vet Dermatol. 2016;27:275–e65. doi: 10.1111/vde.12333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scarampella F, Zanna G, Peano A. Dermoscopic features in canine dermatophytosis: some preliminary observations. Vet Dermatol. 2017;28:255–256. doi: 10.1111/vde.12407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zanna G, Roccabianca P, Zini E, Legnani S, Scarampella F, Arrighi S, Tosti A. The usefulness of dermoscopy in canine pattern alopecia: a descriptive study. Vet Dermatol. 2017;28:161–e34. doi: 10.1111/vde.12359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scarampella F, Zanna G. Dermoscopy in canine and feline alopecia. In: Tosti A, editor. Dermoscopy of the Hair and Nails. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2015. pp. 145–158. [Google Scholar]