Abstract

Health utility, a summary measure of quality of life, has not been previously used to compare outcomes among childhood cancer survivors and individuals without a cancer history. We estimated health utility (0, death; 1, perfect health) using the Short Form-6D (SF-6D) in survivors (n = 7105) and siblings of survivors (n = 372) (using the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort) and the general population (n = 12 803) (using the Medical Expenditures Panel Survey). Survivors had statistically significantly lower SF-6D scores than the general population (mean = 0.769, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.766 to 0.771, vs mean = 0.809, 95% CI = 0.806 to 0.813, respectively, P < .001, two-sided). Young adult survivors (age 18-29 years) reported scores comparable with general population estimates for people age 40 to 49 years. Among survivors, SF-6D scores were largely determined by number and severity of chronic conditions. No clinically meaningful differences were identified between siblings and the general population (mean = 0.793, 95% CI = 0.782 to 0.805, vs mean = 0.809, 95% CI = 0.806 to 0.813, respectively). This analysis illustrates the importance of chronic conditions on long-term survivor quality of life and provides encouraging results on sibling well-being. Preference-based utilities are informative tools for outcomes research in cancer survivors.

Health utility is a summary measure of health-related quality of life, estimated using preference or desirability for living in a particular state of health compared with other states of health or death. While generally used to calculate quality-adjusted life expectancy in cost-effectiveness studies, utilities also provide informative estimates of quality of life as an outcome ( 1 ). To date, this approach has not been used to quantify the impact of cancer treatment–related toxicity in long-term adult survivors of childhood cancer. Expressed on a standardized scale, in which 0 represents death and 1.0 represents perfect health, utility measures allow comparisons of quality-of-life outcomes between patient groups (eg, cancer patients vs HIV patients) and the general US population.

Over 83% of children diagnosed with cancer today will become five-year survivors ( 2 ). Despite this remarkable achievement, 40% of childhood cancer survivors face disabling, severe or life-threatening conditions that threaten to undermine their initial cancer success ( 3 ). The burden of childhood cancer may also impact siblings who experience emotional distress and diminished parental attention because of caregiving demands ( 4 ). Better quantifying the impact of treatment-related toxicity can help identify high-risk groups for interventions that may improve survivor health and well-being, as well as inform the treatment choices for newly diagnosed children.

We estimated health utility scores for childhood cancer survivor (n = 7105) and sibling (n = 372) participants in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) and used the Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (MEPS) as the population comparator (n = 12 803). The CCSS is a multi-institutional, retrospective cohort of more than 14 000 five-year survivors of childhood cancer diagnosed before the age of 21 years between 1970 and 1986 and approximately 4000 siblings ( 5–8 ); the cohort is followed prospectively to document the development of largely self-reported chronic conditions. MEPS is a nationally representative survey of the US noninstitutionalized civilian population age 18 years and older (see Supplementary Materials , available online, for additional details) ( 9 ). Both the CCSS and MEPS collected health status data in 2003 that allowed for the calculation of health utilities via a common metric, the Short Form-6D (SF-6D) ( 10 , 11 ).

We estimated SF-6D utilities for the entire survivor and sibling samples and within sex- and age-specific groups. Among the survivors, we estimated utilities within each original cancer diagnosis group by treatment exposure and by chronic conditions reported in follow-up. Chronic conditions were classified by severity using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE version 4.03) ( 12 ). We assessed differences in health utility across groups by comparing mean values (using Welch’s two-sided t test) and used multivariable linear regression based on a stepwise selection approach to determine the influence of original cancer, treatment, and chronic condition characteristics (using the F-test). Because the large sample size of the CCSS and MEPS can influence statistical significance, we focused on identifying differences in utility scores that were both statistically significant and clinically meaningful to patients ( 13 ). We considered P values of .05 or less to be statistically significant and, based on published results among several patient groups ( 14 , 15 ), defined a minimally important difference (MID) as a .03-point difference in SF-6D score. Statistical analyses were performed in SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

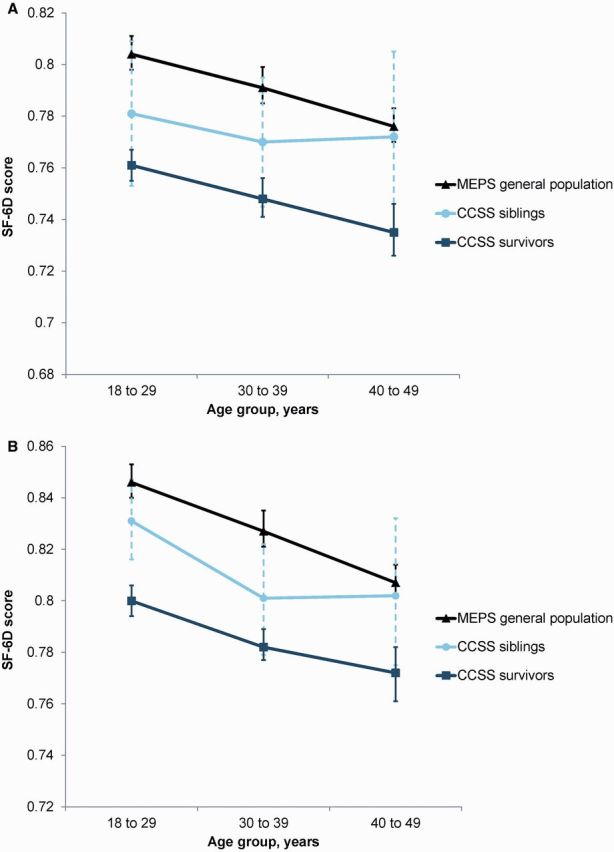

We restricted the analysis to individuals age 18 to 49 years at the time of the health status survey. The MEPS sample consisted of 12 803 individuals, and the CCSS included 7105 survivors and 372 siblings ( Supplementary Table 1 , available online). SF-6D utilities for survivors were statistically significantly lower compared with general population estimates (mean = 0.769, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.766 to 0.771, vs mean = 0.809, 95% CI = 0.806 to 0.813, respectively, P < .001) and reached MID overall and in each age group ( Table 1 ). For both women and men, SF-6D utilities for survivors age 18 to 29 years were similar to general population estimates for people age 40 to 49 years ( Figure 1 ). No clinically meaningful differences in SF-6D scores were detected between siblings of survivors and the general population (mean = 0.793, 95% CI = 0.782 to 0.805, vs mean = 0.809, 95% CI = 0.806 to 0.813, respectively).

Table 1.

Sex-specific SF-6D utility scores for CCSS survivors, CCSS siblings, and MEPS general population: overall and by age-stratum

| Sex and age | Survivors Mean (95% CI) | Siblings Mean (95% CI) | MEPS * Mean (95% CI) | Survivors vs MEPS |

Siblings vs MEPS |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P † | Met MID ‡ criteria? | P † | Met MID ‡ criteria? | ||||

| Both sexes | |||||||

| Overall | 0.769 (0.766 to 0.771) | 0.793 (0.782 to 0.805) | 0.809 (0.806 to 0.813) | <.001 | Yes | .05 | No |

| 18 to 29 y | 0.779 (0.774 to 0.783) | 0.808 (0.791 to 0.826) | 0.826 (0.820 to 0.831) | <.001 | Yes | .22 | No |

| 30 to 39 y | 0.766 (0.761 to 0.770) | 0.784 (0.766 to 0.803) | 0.810 (0.804 to 0.815) | <.001 | Yes | .05 | No |

| 40 to 49 y | 0.753 (0.746 to 0.760) | 0.787 (0.765 to 0.809) | 0.791 (0.787 to 0.796) | <.001 | Yes | .79 | No |

| Women | |||||||

| Overall | 0.751 (0.747 to 0.755) | 0.774 (0.760 to 0.791) | 0.790 (0.787 to 0.795) | <.001 | Yes | .03 | No |

| 18 to 29 y | 0.761 (0.755 to 0.767) | 0.781 (0.753 to 0.809) | 0.804 (0.798 to 0.811) | <.001 | Yes | .09 | No |

| 30 to 39 y | 0.748 (0.741 to 0.756) | 0.770 (0.745 to 0.795) | 0.791 (0.785 to 0.799) | <.001 | Yes | .10 | No |

| 40 to 49 y | 0.735 (0.726 to 0.746) | 0.772 (0.746 to 0.805) | 0.776 (0.770 to 0.783) | <.001 | Yes | .75 | No |

| Men | |||||||

| Overall | 0.787 (0.783 to 0.791) | 0.813 (0.798 to 0.829) | 0.827 (0.823 to 0.832) | <.001 | Yes | .08 | No |

| 18 to 29 y | 0.800 (0.794 to 0.806) | 0.831 (0.809 to 0.852) | 0.846 (0.840 to 0.853) | <.001 | Yes | .11 | No |

| 30 to 39 y | 0.782 (0.777 to 0.789) | 0.801 (0.774 to 0.831) | 0.827 (0.821 to 0.835) | <.001 | Yes | .14 | No |

| 40 to 49 y | 0.772 (0.761 to 0.782) | 0.802 (0.767 to 0.837) | 0.807 (0.801 to 0.814) | <.001 | Yes | .59 | No |

*The reported Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (MEPS) results incorporate sampling and poststratification weights, yielding nationally representative estimates. We include imputed scores in our analyses ( 16 ), which were included in the MEPS dataset, calculated using a proprietary algorithm of QualityMetric, Inc., which is now part of Optum (Eden Prairie, MN). We used the unweighted number of respondents from MEPS for conservatism in the statistical testing. CCSS = Childhood Cancer Survivor Study; CI = confidence interval; MEPS = Medical Expenditures Panel Survey; MID = minimally important difference; SF-6D = Short Form-6D.

† P values based on Welch’s two-sided t test.

‡Defined as a .03-point difference in SF-6D score compared with MEPS.

Figure 1.

Comparison of age-specific SF-6D utility scores among Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) survivors, CCSS siblings, and Medical Expenditures Panel Survey general population by sex. Similar to the general population, SF-6D utility scores for survivors and siblings decreased with age for both women (A) and men (B) . CCSS = Childhood Cancer Survivor Study; MEPS = Medical Expenditures Panel Survey; SF-6D = short form-6D.

Among survivors, differences in SF-6D scores did not reach MID when comparing across original cancer diagnoses, younger vs older age at diagnosis, or different treatment exposure groups ( Supplementary Table 2 , available online). However, SF-6D scores did vary by the number and severity of chronic conditions reported ( Table 2 ). Survivors who reported no conditions had SF-6D scores comparable with general population estimates (mean = 0.809, 95% CI = 0.804 to 0.815, vs mean = 0.809, 95% CI = 0.806 to 0.813, respectively, P = .99). In contrast, compared with those who reported no conditions, SF-6D scores reached MID and were statistically significantly lower in survivors who reported two or more conditions ( P < .001). Survivors with multiple severe, disabling or life-threatening conditions (CTCAE grades 3 or 4) had even greater decrements compared with the general population (see also Supplementary Figure 1 , available online). Multivariable models found that older attained age, female sex, and number of chronic conditions were associated with statistically significant SF-6D score decrements ( P < .003) ( Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Figure 2 , available online).

Table 2.

SF-6D utility scores for CCSS survivors by number and severity of chronic conditions *

| Characteristic | No. | SF-6D Mean (95% CI) | Compared with no conditions |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P † | Met MID ‡ criteria? | |||

| No conditions | 1475 | 0.809 (0.804 to 0.815) | Reference | Reference |

| No. of conditions, grades 1-4 | ||||

| 1 | 1538 | 0.795 (0.789 to 0.800) | <.001 | No |

| 2 | 1113 | 0.772 (0.765 to 0.779) | <.001 | Yes |

| ≥3 | 2979 | 0.735 (0.729 to 0.739) | <.001 | Yes |

| No. of conditions, grades 3-4 only § | ||||

| 1 | 286 | 0.785 (0.771 to 0.798) | <.001 | No |

| 2 | 518 | 0.725 (0.713 to 0.736) | <.001 | Yes |

| ≥3 | 198 | 0.695 (0.677 to 0.713) | <.001 | Yes |

| Maximum severity of condition(s) ‖ | ||||

| Grade 1 | 1532 | 0.777 (0.771 to 0.782) | <.001 | No |

| Grade 2 | 1623 | 0.772 (0.766 to 0.778) | <.001 | Yes |

| Grade 3 | 1604 | 0.746 (0.739 to 0.752) | <.001 | Yes |

| Grade 4 | 871 | 0.727 (0.718 to 0.736) | <.001 | Yes |

*Childhood Cancer Survivor Study reported health conditions were graded by severity based on the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE version 4.03) as follows: grade 1 (mild), grade 2 (moderate), grade 3 (severe or disabling), and grade 4 (life-threatening) ( 12 ). CCSS = Childhood Cancer Survivor Study; CI = confidence interval; MID = minimally important difference; SF-6D = Short Form-6D.

† P values based on Welch’s two-sided t test.

‡Defined as a .03-point difference in SF-6D score compared with survivors with no conditions.

§Individuals may have also reported grade 1 or 2 conditions.

‖For individuals who had more than one condition, severity was based on maximum grade.

Using the CCSS cohort, the current analysis documents that chronic conditions substantially and negatively affect the quality of life of adult survivors of childhood cancer. In particular, the number and severity of chronic conditions are largely responsible for poor health-related quality of life as estimated with utility scores, not original cancer diagnosis or treatment. Moreover, our analysis shows that younger survivors (age 18-29 years) report a quality of life comparable with general population individuals who are approximately two decades older, adding to the growing evidence that survivors experience accelerated aging because of chronic conditions ( 17 ). Our findings are encouraging for the 20% of survivors who reported no chronic conditions, as well as for siblings of childhood cancer survivors; both groups’ utility scores were similar to those from the general population.

Limitations to our study include that chronic conditions in the CCSS were self-reported, although estimated SF-6D scores reflect quality of life decrements that may be associated with undiagnosed or unreported conditions. Additionally, the MEPS comparison group includes participants with and without chronic conditions prevalent in the general population (hypertension, heart disease, high cholesterol, emphysema, chronic bronchitis, diabetes, cancer, arthritis, or stroke). However, if we restrict the comparison to include only MEPS participants and survivors with any chronic condition, SF-6D scores were similar (mean = 0.758, 95% CI = 0.752 to 0.765, vs mean = 0.758, 95% CI = 0.755 to 0.762, respectively, P = .99), providing further support that cancer survivorship itself is not associated with quality-of-life decrements. As with all utility measures, the SF-6D may not fully capture the entirety of well-being ( 18 ). We defined the MID based on criteria established by individuals without a cancer history ( 14 , 15 ); survivors may view smaller (or larger) differences to be clinically meaningful.

Our findings, which represent the first use of utility scores to illuminate quality-of-life differences among adult survivors of childhood cancer and nonsurvivors, highlight the importance of chronic conditions on health-related quality of life for childhood cancer survivors and provide encouraging results on the impact of the cancer experience on long-term sibling well-being. Use of utility scores may provide a novel framework for clinicians and researchers engaged in pediatric cancer treatment and trials as they consider therapy choices for childhood cancer.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (U24CA55727, G. T. Armstrong, Principal Investigator). Support to St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital was also provided by the Cancer Center Support (CORE) grant (CA21765) and the American Lebanese-Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC). Dr. Yeh was supported by the National Cancer Institute (K07CA143044).

Notes

The study funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russel LB, Weinstein MC , eds. Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine . New York: : Oxford University Press; ; 1996. . [Google Scholar]

- 2. Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M , et al. . SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2012, http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2012/ , based on November 2014 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2015. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Accessed July 18, 2015. .

- 3. Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA , et al. . Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer . N Engl J Med. 2006. ; 355 ( 15 ): 1572 – 1582 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Woodgate RL. Siblings' experiences with childhood cancer: a different way of being in the family . Cancer Nurs . 2006. ; 29 ( 5 ): 406 – 414 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Phillips SM, Padgett LS, Leisenring WM , et al. . Survivors of childhood cancer in the United States: prevalence and burden of morbidity . Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev . 2015. ; 24 ( 4 ): 653 – 663 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Robison LL, Armstrong GT, Boice JD , et al. . The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: a National Cancer Institute-supported resource for outcome and intervention research . J Clin Oncol. 2009. ; 27 ( 14 ): 2308 – 2318 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Robison LL, Mertens AC, Boice JD , et al. . Study design and cohort characteristics of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: a multi-institutional collaborative project . Med Pediatr Oncol. 2002. ; 38 ( 4 ): 229 – 239 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Leisenring WM, Mertens AC, Armstrong GT , et al. . Pediatric cancer survivorship research: experience of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study . J Clin Oncol . 2009. ; 27 ( 14 ): 2319 – 2327 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . Medical Expenditures Panel Survery (MEPS). http://www.ahrq.gov/research/data/meps/index.html . Accessed January 14, 2014.

- 10. Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36 . J Health Econ . 2002. ; 21 ( 2 ): 271 – 292 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brazier JE, Roberts J . The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-12 . Med Care . 2004. ; 42 ( 9 ): 851 – 859 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program . Common Termiology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), version 4.03 . Bethesda, MD: : National Cancer Institute; . [Google Scholar]

- 13. McGlothlin AE, Lewis RJ. Minimal clinically important difference: defining what really matters to patients . JAMA . 2014. ; 312 ( 13 ): 1342 – 1343 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Feeny D, Spritzer K, Hays RD , et al. . Agreement about identifying patients who change over time: cautionary results in cataract and heart failure patients . Med Decis Making. 2012. ; 32 ( 2 ): 273 – 286 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Walters SJ, Brazier JE. What is the relationship between the minimally important difference and health state utility values? The case of the SF-6D . Health Qual Life Outcomes . 2003. ; 1 : 4 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity . Med Care. 1996. ; 34 ( 3 ): 220 – 233 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Robison LL, Hudson MM. Survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: life-long risks and responsibilities . Nat Rev Cancer. 2014. ; 14 ( 1 ): 61 – 70 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen G, Khan MA, Iezzi A, Ratcliffe J, Richardson J. Mapping between 6 Multiattribute Utility Instruments . Med Decis Making. 2016. ; 36 ( 2 ): 160 – 175 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.