Abstract

Introduction

Advances in longevity and medicine mean that many more people in the UK survive life-threatening diseases but are instead susceptible to life-limiting diseases such as dementia. Within the next 10 years those affected by dementia in the UK is set to rise to over 1 million, making reliance on family care of people with dementia (PWD) essential. A central challenge is how to improve family carer support to offset the demands made by dementia care which can jeopardise carers’ own health. This review investigates ‘what works to support family carers of PWD’.

Methods

Rapid realist review of a comprehensive range of databases.

Results

Five key themes emerged: (1) extending social assets, (2) strengthening key psychological resources, (3) maintaining physical health status, (4) safeguarding quality of life and (5) ensuring timely availability of key external resources. It is hypothesized that these five factors combine and interact to provide critical biopsychosocial and service support that bolsters carer ‘resilience’ and supports the maintenance and sustenance of family care of PWD.

Conclusions

‘Resilience-building’ is central to ‘what works to support family carers of PWD’. The resulting model and Programme Theories respond to the burgeoning need for a coherent approach to carer support.

Keywords: adult resilience, Alzheimer's disease, dementia, family carers, realist review

Introduction

Dementia constitutes one of the most serious challenges facing families and health and social care services in the UK.1 Increasing longevity in the UK has led to an ageing UK population and a 62% rise in the number of people with dementia (PWD) since 2007.2 Advances in medicine mean that many more people are surviving life-threatening diseases but susceptible to life-limiting diseases such as dementia.3 Within the next 10 years the number of people affected by dementia in the UK is set to rise to over 1 million and it is estimated this number will exceed 2 million by 2051.4 The most prevalent form of dementia is Alzheimer's disease which accounts for around 62% of all cases.5 Since there is no cure for their illness PWD will increasingly find themselves in situations in which their lives need to be managed in older age.6 The relatively prolonged pathology of Alzheimer's disease which lasts up to 15 years7 and the progressive and severe disabilities it can produce make long-term care essential.8

However, a central difficulty remains that formal care services are not equipped to take over the responsibility for long-term care. Complete reliance on formal care provision is estimated at £119 billion9 which exceeds the entire UK 2015/16 NHS budget, set at £93 billion.10 Current policy and guidelines therefore support the continuation of long-term, informal care provision via family care,11 a view that meets the desires of the majority of PWD who prefer to live out their lives within the community they belong9 and of their family members who largely endorse this choice. At present, a major obstacle to achieving this is that the majority of family carers of PWD rely on ‘trial and error’ approaches to carrying out the carer role12 that cannot guarantee long-term success.13

An alternative is to develop our understanding of ‘what works to support family carers of PWD’, and crucially also how, i.e. the underlying contexts and mechanisms that generate effective and sustained family care. This would pave the way for the more strategic provision of family support that maximizes those resources carers already possess while finding more effective ways to allocate external support, e.g. from formal health-care services.13 Optimizing family carer support should also focus on measures that safeguard the health of family carers themselves, a factor that remains critical to enabling longer-term family care of PWD.

The present review forms part of a wider project that will subsequently be informed by field work to further examine and explore the findings.

Objectives and focus of review

A recurring theme in family carer research is the polarity of carer response to the challenges of taking on the role.14 While some carers become overwhelmed by the experience others appear to not only maintain stability but may even report improvements over time.14 The review investigates key factors that relate to ‘what works to support family carers of PWD’ and how this knowledge might be more widely promoted to benefit all carers of PWD.

Methods

Rationale

Traditional review methods such as systematic review and meta-analysis tend to focus on outcomes to provide information that is mainly descriptive and assume outcomes are generated by linear causation.15 However, where complex social issues are investigated causation may often be non-linear, requiring approaches with greater explanatory power that offer comprehensive explanations of ‘process’. A Realist approach16,17 was deemed appropriate based on its ability to provide useful tools for synthesizing complex and wide-ranging evidence from the diverse sources predicted to emerge and to illuminate not only ‘what works’ but also ‘how’. While full Realist reviews engage in a much longer exploration of the literature and period of ‘testing’, rapid realist reviews (RRRs) have recently emerged to facilitate a speedier transition from research to policy and practice.18 This is particularly useful during the initial phases of a multi-phase project where research findings need to be rapidly adapted and iteratively refined to take account of emerging evidence. RRRs have proved effective where there is a small but emerging body of evidence on which future policies might be based but where there is insufficient evidence to support a Realist Synthesis of the existing literature.19 These criteria applied to the present study.

The present RRR attempts to adhere to the Realist publication standards guidelines20 as faithfully as possible. However, the recency of RRRs as an approach means there is also some necessary reliance on the handful of RRRs already in existence to inform the methodology employed. In particular, replication of the five step review process employed by Willis et al.19 to streamline and accelerate the review process. Further, since the present review forms part of a PhD thesis the expert, practitioner and lay expertise normally offered by an expert/reference panel was instead provided by the Supervision team who represent the co-authors of the review.

Scoping review

The search process involved an initial scoping review based on the Google and Google Scholar search engines to identify relevant abstracts. This indicated that the evidence base was relatively narrow with little consensus regarding the broad question of ‘what works to support family carers of PWD’. A comprehensive second string search of the literature via electronic databases (including grey literature) was deemed essential in order to derive sufficient evidence to formulate reasonable hypotheses.

Searching processes

The second string search of the literature was conducted using more refined search terms and guided by inclusion criteria (see Table 1). This included filtering of articles to achieve breadth of coverage, relevance and depth.

Table 1.

Search process, search terms and number of abstracts selected per database to be assessed against the inclusion criteria as a precursor to selection for extraction

| ’Scoping Review’ based on the Google & Google Scholar search engines to glean background information concerning the research question: ‘What works to support family carers of PWD?’ This confirmed the initial contention that there was a relatively narrow database surrounding this question. | ’Second string search’ of more bespoke databases related to the scientific, medical, physical, psychological and social science bases of the research question. Principally, this included any documents relating to the family care of PWD or Alzheimer's disease; any efforts or interventions designed to support family carers; barriers to support & current health policies relating to this. | ’Third string iterative search’ based around selection of ‘resilience’ and ‘resilience-building’ representing the most plausible overarching candidate mechanism & middle-range-theory to account for the more specific carer outcome of supporting the long-term maintenance & sustenance of the family care of PWD. |

Search Results

|

Search Terms

|

Inclusion criteria descriptions:

(1) Article discusses dementia within the context of family care, informal care and unpaid care.

(2) Article discusses Alzheimer's disease within the context of family care, informal care and unpaid care.

(3) Article discusses what works to support the care of PWD/Alzheimer's disease.

(4) Article discusses potential barriers to the care of PWD/Alzheimer's disease.

(5) Article discusses potential interventions employed to support the care of PWD/Alzheimer's disease.

(6) Article discusses the health policies surrounding the care of PWD/Alzheimer's disease.

(7) Article discusses the health policies surrounding the care of PWD/Alzheimer's disease and offers recommendations for the future based on research evidence and stakeholders’ experiences.

aArticles meeting any of the above criteria were retrieved for full text screening, even where only one criterion might be met. Full text articles meeting inclusion criteria proceeded to full extraction. Articles not meeting any of the above criteria were excluded from Results, but where relevant helped to inform the background and introduction to the review.

Five main databases were interrogated for relevant abstracts that focused on both general and specific information and also included information on the psychological dimension of dementia care since it is well established that the majority of carers of PWD will encounter psychological challenges.21 Searches also included grey literature based on voluntary sector reports. Articles meeting any of the inclusion criteria were retrieved for full text screening. Full text articles meeting inclusion criteria proceeded to full extraction (further details concerning this process can be obtained by contacting the corresponding authors). Articles not meeting any of the above criteria were excluded from the results, but where relevant helped to inform the background to the project.

Data extraction

Selection and appraisal of the documents identified five broad themes encompassing different areas of family carer support (see Results). While this proved helpful in providing some necessary coherence to the findings what was notably absent was a means to provide cohesion among these disparate categories. A main setback to providing more effective carer support is that at present interventions tend to lack coordination.22 A unified theory was therefore needed to explain all the observed patterns and uniformities in the data, i.e. an overarching middle-range theory (MRT).23 This required further consideration of what in Realist terms the principal ‘outcome’ was intended to be with regard to the majority of interventions explored by the review. Thus, ‘outcome’ was more clearly operationalized as ‘those measures designed to augment carers’ capacity to maintain and sustain the longer-term family care of PWD despite the challenges this may present’.

Retroductive inquiry, including exploration of a range of potential MRTs, was conducted to establish how this outcome might be generated. These included factors previously associated with the ability to maintain a carer role despite adverse circumstances: extraversion,24 optimism25 and hardiness.26 However, a main drawback is that these primarily represent personality traits. As such they are relatively stable in later adulthood27 and not therefore amenable to interventions designed to modify them to improve health outcomes. A further MRT that was considered was ‘fear’ and in particular, fear of the consequences of cessation of family care and subsequent institutionalization of the PWD as a potential overarching mechanism driving the maintenance of family care. However, it seemed doubtful that the chronic experience of fear provides any long-term solution to ‘what works to support family carers’.

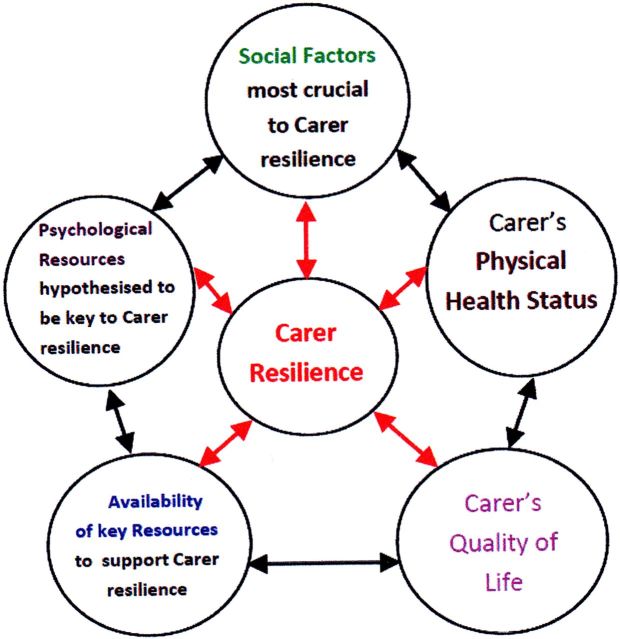

Ultimately, the contention was raised that what connected all the carer support measures examined was their ability to contribute to ‘carer resilience’ to generate the outcome of sustaining long-term family care of PWD (see Fig. 1). ‘Resilience’ is here operationalized as ‘Resilience bolstered by assets and resources28 that combine to provide a cumulative buffer against adversity29 as well as by supportive behavioural choices and actions’. ‘Mechanisms’ is defined here as (a) those key resources that remain external to the family carer such as principal social assets and key service support resources; (b) those key resources that remain internal to the family carer such as carers’ physical health status and psychological resources associated with resilience-building; and (c) how all these combine to influence carers’ quality of life (QOL). This definition remains consistent with recent Realist interpretation of ‘mechanism’ as a combination of resources, some of which will originate from external sources and some of which are inherently internal resources including inner reasoning/actioning (for a review see Dalkin et al.30). Although there appeared to be an implicit logic to this suggestion that seemed self-evident, re-engagement with the literature was warranted to substantiate this theory.

Fig. 1.

Initial model outlining five main areas for family carers support based around the MRT that resilience is central to 'what works' to support the long-term maintenance and sustenance of family care.

A third string literature search was therefore conducted to establish how ‘resilience’ might be related to the support of family carers of PWD. This revealed that ‘resilience’ was related to each of the five themes (see Table 2) and supported the MRT that ‘resilience’ and the related process of ‘resilience-building’ might represent the cornerstone supporting those factors that work to support family carers of PWD.

Table 2.

Programme theories based upon ‘what works to support family carers of PWD’ and links with resilience

| Action Theme | (C) Context provided by Strategy/Intervention | (M) Potential Mechanisms & How they may operate to instil Resilience to generate (O) outcome-defined as ‘support for family carers of PWD’ & Bases for links with Resilience. References are in superscript. |

|---|---|---|

| Action Theme 1: Extending Social Assets | (i) Strong Relational support network | Social support provides effective support for carers;31 provides protective factor against carer depression;32 reinforces ability to cope;31 reduces number of hours engaged in daily care by a single family member; moderates perceived QOL;33 Social support has often been correlated with resilience33–36 |

| (ii) Good relationship with PWD | Reduces potential social tensions alleviates anxiety/stress37 reduces behavioural management issues that can otherwise promote high levels of stress;38,39 positive reappraisal of carer events promotes a positive carer-PWD atmosphere40 | |

| (iii) Fostering effective Service provider support for carers | Additional emotional support provides an extra buffer against carer depression;41 greater trust needed to be fostered between service providers & carers;42 telephone support can provide effective emotional support43 | |

| (iv) Carers & PWD well integrated within dementia friendly community | Encourages acceptance of carers & PWD within the community reducing potential anxiety/tension;44 facilitates socialization within the community to encourage wider social support & wider engagement in social activities to enhance QOL44 | |

| (v) Regular Voluntary sector support & close links with other carers | Less formal peer support reduces social isolation & increases emotional support remove potential triggers for carer depression;32,45,46 older carers may have no relational network & may therefore rely more on the voluntary sector for support47 | |

| Action Theme 2: Strengthen Key Psychological Resources available to carer | (i) Self-efficacy (SE) (the belief that one has the capability to successfully engage in specific actions and exercise control over events that affect one's life)48 | Raises carer perception of controllability over care situation to reinforce carers’ internal locus of control, self reliance, resilience & perceived capacity to master new domains;48 high locus of control linked to lower carer perception of care as ‘burden’.49 Perception of care as ‘burden’ is linked to cessation of family care;49 SE has demonstrated success by enabling carers to select more effective behavioural choices & actions in relation to dementia care which fosters resilience.50 High SE is linked to robustness51 which has close associations with resilience. |

| (ii) Hope (a future goal orientation, the belief that goals can be attained, & the cognitive-motivational beliefs that pathways to goals can be created & pursued) 52 | Mediates psychological distress;53 remaining positive in outlook provides a buffer against depression;54 mobilizes resources to adapt to changes;55 promotes problem-solving & growth-seeking behaviours;56 reducing social isolation & increasing carer locus of control boosts hope.57 Resilience can be ‘bolstered by supportive behavioural choices and actions’,29 i.e. encouraging carers to become more proactive in self-help via problem-solving and growth-seeking behaviours56 | |

| (iii) Coping ability (the process by we which peopl manage stress)58 | Acceptance-based coping may permit meaning & growth to be derived from the care situation;59 perceived ability of carers to cope may provide a buffer against sleep loss;60 coping strategies can be learned & adapted;61 carers may require different coping strategies at different stages of dementia: e.g. problem-solving to begin with, cognitive reappraisal during middle stages & behaviour management during later stages;38,39 carers with fewer coping strategies may be more vulnerable to stress;62 enhancing carer coping skills is high on the agenda where carer interventions are generally considered.37 Positive coping skills have been identified as important to resilience.33 | |

| Action Theme 3: Maintaining Carer's Physical Health Status | (i) Perceived level of carer health | Carers’ health is mutually bound to the PWD's health rather than mutually exclusive35 Carers’ health status ultimately decides between maintenance of family care or cessation46 Safeguarding carers’ own health remains a priority in dementia care via a supportive health-care system42 While the actual physical health status of carers remains crucial so too does how well they perceive their general health, e.g. perceived levels of stress can make a unique contribution to depression63 & carers of PWD are vulnerable to depression.21 Strong links have been drawn between the maintenance of good physical health & resilience.64 |

| (ii) Objective measures of carer health as defined by General Practitioner (GP) check ups | The importance of maintaining carers’ health in order to sustain family care of PWD via regular contact with GP,65 a factor recognized by the as reflected in the Carers Act (2014).66 | |

| (iii) Adherence to a healthy, balanced diet | Since chronic fatigue is a commonly cited issue among long-term carers67 the regular inclusion of slow-burning starches to increase energy & stamina might provide a necessary boost to carers’ energy levels. Since the majority of carers of PWD are 60 years of age or over46 they may be vulnerable to anaemia, the commonest haematological condition found among older population groups.68 Anaemia caused through iron deficiency can lead to symptoms of general fatigue. An iron rich diet &/or the use of iron supplements may therefore prove beneficial for carers of PWD. | |

| (iv) Regular physical activity | Regular physical activity carries physical & psychological health benefits for carers69 & may include brisk walking for 15 min/day to increase cardiovascular fitness and promote anxiolytic effects that can reduce sensitivity to stress. Exercise may be combined with pleasurable activities to promote positive affect & enhance QOL;70 Exercise can promote SE.71 | |

| (v) Perception of generally good quality/quantity of sleep | Carer sleep deprivation caused by the sundowning phenomenon associated with PWD remaining active during the night can induce sleep deprivation, exhaustion & ultimately reduce carers’ perception of being able to cope46 & is a key predictor of cessation of family care,72 possibly via its links with depression.63 Promotion of uptake of respite care may provide one way of supporting carers’ management of sleep. Supportive behavioural choices and actions enhance resilience29 & these might include maintaining an energy balance between effort expended in carrying out the daily care of PWD and appropriate dietary intake as well as regular physical activity.The combination of healthy diet & regular physical activity has been found to contribute to resilience in older age73 & this is relevant to the majority of carers of PWD who are aged 60 or over.46 | |

| Action Theme 4: Safeguard Carer's QOL | (i) Opportunities to experience positive affect (feelings of active pleasure) | QOL is an important mediator of carer health & wellbeing74 with low QOL associated with burnout & depression75 which in turn predict cessation of family care;72 key to maintaining carer QOL is ensuring that time is set aside each day to engage in activities that by sustaining hobbies, interests and outlets for activities outside the care environment & this has been shown to exert a positive impact on carers;70 frequent engagement in pleasurable activities that promote positive affect promotes health benefits.73 Some authors have explicitly operationalized ‘resilience’ as QOL, emphasizing the close links between the two;33 experiencing positive emotions (positive affect) via daily life experiences correlates with individual resilience76 |

| (ii) Maintenance of affect balance | Maintaining affect balance is important in order to keep moods & emotions in check & to ensure that emotional experiences are not continually negatively biased; ability to self-moderate positive affect (how pleasurable experiences are perceived) may be higher in older adults than for their younger counterparts,77 perhaps due to increased emotional maturity & emotional strength. However, this still relies on maintaining opportunities to engage in positive affect in the first instance.78 External resources may need to be made available in order to ensure this, e.g. respite care, day care, sitting services. | |

| (iii) Subjective experience of life, living & domains of life such as work, leisure & family remain generally positive | Subjective experience of care as ‘burden’ is strongly linked to the cessation of family care of PWD.79 By contrast, ability of carers to frame their experiences more positively can mediate the impact of the chronic stress commonly associated with carers of PWD;80 cognitive reappraisal is a learned strategy that can be taught to carers of PWD & has shown success in promoting positive subjective experience81 | |

| (iv) Finding Self-development, Growth & Meaningfulness in life through the care experience | The concept of finding ‘caregiver meaning’ through the experience of caring for a PWD represents a useful and adaptive coping strategy82 that may be more readily accepted as we move into our 1950s.83 This factor is relevant since the majority of carers of PWD are aged 60 or over.46 Finding positive dimensions to the carer experience such as finding growth, meaning & development through it can provides a constructive coping strategy to mediate the impact of chronic stress on carers of PWD.84 Both the availability of emotional support & engagement in pleasurable activities to experience positive affect may contribute to this adaptive coping strategy. More complex techniques such as cognitive restructuring may demand more intensive external support, i.e. via mindfulness training. The ability to perceive meaning in life despite adverse circumstances has been identified as a factor relating to resilience.85 | |

| Action Theme 5: Ensure timely Availability of Key External Resources | A central issue is that a reported 47% of family carers of PWD do not receive any external support at all.42 How carers of PWD cope may be very much dependent on the external resources available.40 ‘Resilience’ is here defined as ‘resilience bolstered by assets and resources’28 that combine to provide a cumulative buffer against adversity’.29 External resources that have demonstrated success in supporting carers of PWD despite the multiple challenges they face include but are not limited to: | |

| ||

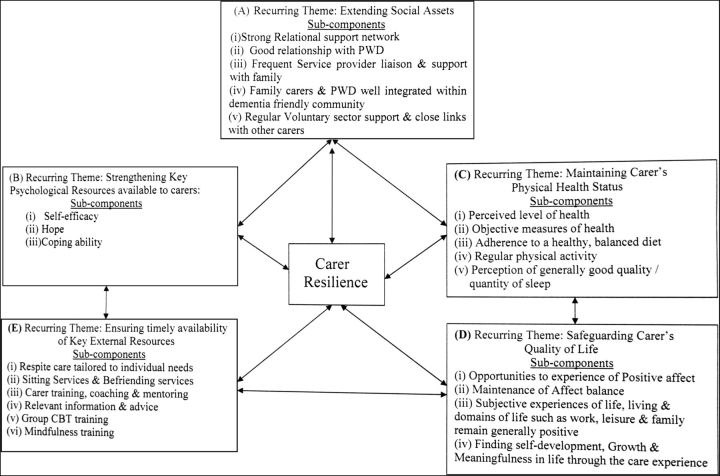

‘Unpacking’ the underlying mechanisms within the interventions uncovered by the third string literature search revealed several salient sub-components (strategies, programmes or interventions) within each of these five domains (see Fig. 2). These were explored to examine how they might be adapted, combined and usefully exploited to strengthen carer resilience. For example, QOL was found to be an important mediator of carer health and wellbeing,31 with low QOL associated with burnout and depression,75 symptoms commonly experienced by carers of PWD21 as well as predictors for cessation of family care.88,95 Key to maintaining carer QOL is ensuring time is set aside to sustain hobbies and interests which has been shown to exert a positive impact on carers.70 Frequent engagement in pleasurable activities that promote positive emotions promotes health benefits73 and has been correlated with individual resilience.76 However, maintaining opportunities to engage in QOL may require differentiated (i.e. day, overnight or more extended) availability of external resources such as respite care which has demonstrated effectiveness in extending family care of PWD86 (further examples are illustrated in Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Expanded framework for how carer resilience might be generated to support family carers of PWD. 'Quality of Life' is defined here according to the WHO interpretation: 'individuals' perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns—a broad ranging concept affected in a complex way by the person's physical health, psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, personal beliefs and their relationship to salient features of their environment.101 Each of the remaining four themes are defined by their sub-components. Specific definitions are provided for the psychological resources: (i) self-efficacy, (ii) hope and (iii) coping ability (see Table 2).

Results

Initial searches identified 217 documents that met the inclusion criteria following screening. Selection and appraisal of the documents identified five broad themes encompassing different areas of family carer support (see Fig. 1). Data synthesis and analysis led to the refinement and consolidation of the five recurrent themes identified from the literature. This led to the contention that ‘resilience’ might be strongly associated with achieving this more specific ‘carer support’ outcome.

The third string literature search revealed several salient sub-components (i.e. specific or individual strategies, programmes or interventions) within each of these five domains (see Fig. 2) and related Programme Theories (PTs) (see Table 2 below).

Main findings of the study

RRR was chosen as a research method capable of detailed investigation of ‘what works’ as well as ‘how’ via explanations for the underpinning mechanisms by which certain strategies or interventions might work and to bring some much needed consensus to this emergent topic. Investigation of ‘What works to support family carers of PWD’ based on the findings from a comprehensive search of the published literature spanning the past decade, including grey literature, revealed multiple strategies or interventions from a diverse range of findings. However, a main difficulty found was the lack of coherence among the disparate findings. This prevented a more co-ordinated, strategic approach towards carer support that harnessed the most effective strategies, based not only on a knowledge of ‘what works’ but also ‘how it works’.

The MRT that ‘resilience’ and its contingency ‘resilience-building’ might play a central role as the underpinning mechanism that generates support for family carers of PWD, by augmenting carers’ capacity to maintain and sustain the longer-term family care of PWD, crucially serves to provide a unifying principle. Crucially, this offers a means to establish a more comprehensive, coherent and cohesive framework for supporting family carers that harnesses the benefits of multiple strategies. These can be usefully adapted, combined and strategically exploited around the clearer premise of ‘strengthening carer resilience’. The MRT serves to demystify and ‘unpack’ what it is that we mean when we are discussing ‘supporting carers’ and how this might be achieved, i.e. ‘what works’. This helps to meet the burgeoning need to unravel some of the complexity inherent to ‘what works to support carers of PWD’ and to bring some much needed consensus in response to this important question. The resulting model and PTs provide a relatively comprehensive and cohesive framework for how carer resilience might be generated. They also provide a framework for subsequent empirical testing (see Table 2).

The MRT is also supported by more recent interpretations of ‘resilience’ that emphasize its role as a ‘process’ that develops across the lifespan,96 as adults continue to develop cumulative strength and knowledge based on their experiences of how to adapt to changing circumstances and new challenges (for a review, see Luthar et al.97). Moreover, a view that is beginning to take hold is that older adults possess a lifetime's accumulation of experiences of striving and succeeding in overcoming adversity, making resilience a developmental process that continues across the course of adults’ lifespan.98 A greater accumulation of such experiences over time may mean that older adults who represent the majority of carers of PWD46 may actually be better placed than their younger counterparts in terms of their potential to harness and exploit this valuable resource.98 Of particular interest to the present research is how ‘resilience’ as a process might be susceptible to mediation to support carers, a concept which has recently become a central component of the ‘Changing Minds, Improving Lives’ programme which forms part of the current modernization of dementia services in Scotland.99

Arguably, this calls for a move away from traditional ‘burden of care’ models than automatically predict poor carer outcomes irrespective of any carer support that may be provided. Focussing attention on carer ‘resilience’ and ‘resilience-building’ effectively reframes how we perceive the carer role and how carers themselves can perceive it, with the emphasis switched to how caregiving can be made successful.

What is already known on this topic

Advances in longevity and medicine mean that many more people in the UK survive life-threatening diseases but are instead susceptible to life-limiting diseases such as dementia. Within the next 10 years those affected by dementia in the UK is set to rise to over 1 million, making reliance on family care of PWD essential. A central challenge is how to improve family carer support to offset the demands made by dementia care which can jeopardise carers’ own health. This review explored the contribution of over a thousand published documents that related to dementia care. What was notably absent was any consensus in the data regarding ‘what works to support family carers of PWD’ and more fundamentally ‘how’ the disparate array of strategies ‘work’. This is despite a burgeoning need to find a coherent approach to family carer support.

What this study adds

The present review adds to the existing literature by highlighting the potential for a more coherent and cohesive means of organizing and orchestrating support for family carers of PWD from within five key areas that focus positively and constructively on the relative strengths of family carers, particularly their capacity for resilience and resilience-building. This MRT crucially serves to unravel some of the complexity inherent to what supports carers of PWD by offering a guiding principle and clear rationale to inform the mobilization of a wider range of individual and external resources that can be combined and integrated to promote a more holistic, comprehensive and positive approach to supporting carers than might otherwise be achieved. The resulting model and PTs respond to the burgeoning need for a more coherent and strategic approach to carer support that harnesses the benefits of a wider range of resources. Arguably, this calls for a paradigm shift in how family care of dementia is perceived, i.e. away from traditional ‘burden of care’ models that focus on failure and towards models of care that reinforce the sustainability of family care, i.e. by harnessing family carers’ potential for resilience and strength.

The resulting model and PTs also provide a platform from which to conduct subsequent empirical testing of the hypotheses and to investigate how further contexts might be created that similarly promote resilience in carers, as well as how resilience might support adult health more generally.

RRRs lend themselves to emerging research topics such as the present study by producing explanatory accounts of what works based on a wide range of sources, while the streamlined review process provides a rapid and timely response to pressing policy needs.

Limitations to this study

The model does not represent an exhaustive taxonomy. Rather, it serves to highlight main areas hypothesized to support carers. Both the model and PTs remain iterative and subject to further refinement during subsequent ‘testing’ and as new evidence emerges from future research.

The review presents a challenge to the traditional biomedical interpretation of adult resilience that emphasizes resilience deficits and decline100 rather than an opportunity to exploit it as a key resource in the promotion of strength and growth in health contexts. The question of how family carers of PWD can best be supported and how resilience may more generally contribute to the health of older adults remain emergent areas for research.

Further studies are also warranted that focus more exclusively on how different social contexts and associated demographic factors influence how resilience operates.

RRRs represent a recently developed methodology, subject to further iterative refinement.

Funding

Mark Parkinson is a PhD student funded by Fuse, the Centre for Translational Research in Public Health (www.fuse.ac.uk). Fuse is a UK Clinical Research Collaboration (UKCRC) Public Health Research Centre of Excellence. Funding for Fuse from the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Medical Research Council, the National Institute for Health Research, under the auspices of the UKCRC, is gratefully acknowledged. The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily represent those of the funders or UKCRC. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Milne A. The ‘D’ word: reflections on the relationship between stigma, discrimination and dementia. J Ment Health 2010;19(3):227–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Prescribing and Primary Care Team. The Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC). Quality Outcomes Framework, Recorded Dementia Diagnoses – 2013–14, Provisional Statistics. England: Crown Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ham C, Dixon A, Brooke B. Transforming the Delivery of Health and Social Care: The Case for Fundamental Change. England: The King's Fund, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alzheimer's Society. Dementia UK Overview, 2nd edn.London: Alzheimer's Society Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5. The Alzheimer's Society Demographics and Statistics. 2013. http://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/documents_info.php?documentID=412 (6 December 2015, date last accessed).

- 6. WHO Mental Health and Older Adults Fact Sheet 2016. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs381/en/ (August 2016, date last accessed).

- 7. Vitaliano PP, Zhang J, Scanlan JM. Is caregiving hazardous to one's physical health? A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 2003;129:946–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yokoi T, Okamura H. Why do dementia patients become unable to lead a daily life with decreasing cognitive function. Dementia 2012;12(5):551–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carers UK and the University of Leeds. Carers UK Valuing Carers 2011: Calculating the Value of Carers’ Support. London: Carers UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Roberts A, Marshall L, Charlesworth A. A Decade Of Austerity? The Funding Pressures Facing the NHS from 2010/11 to 2021/22. London: Nuffield Trust, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11. H.M. Government. Caring for our Future. Reforming Care and Support. London: Crown Press, 2012. Department of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gaugler JE, Kane RL, Kane RA et al. The longitudinal effects of early behavior problems in the dementia caregiving career. Psychol Aging 2005;20:100–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nolan M, Ryan T, Enderby P et al. Towards a more inclusive vision of dementia care practice and research. Dementia 2002;1(2):193–11. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gaugler JE, Davey A, Pearlin LI et al. Modeling caregiver adaptation over time: the longitudinal impact of behavior problems. Psychol Aging 2000;15(3):437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pawson R. Evidence-based policy – the promise of realist synthesis. Evaluation 2002;8(3):340–58. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pawson R. Evidence-based Policy: A Realist Perspective. London: Sage Publications, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pawson R. The Science of Evaluation: A Realist Manifesto. London: Sage, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Saul JE, Willis CD, Bitz J et al. A time-responsive tool for informing policy making: the rise of rapid realist review. Implement Sci 2013;5(1):103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Willis CD, Saul JE, Bitz J et al. Improving organizational capacity to address health literacy in public health: a rapid realist review. Public Health 2014;128(6):515–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G et al. RAMESES publication standards: realist syntheses. BMC Med 2013;11(1):21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hirst M. Carer distress: a prospective, population-based study. Soc Sci Med 2005;61(3):697–08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Oliver D. Leading Change in Diagnosis and Support for People Living with Dementia. The King's Fund 2015. http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/blog/2015/02/leading-change-diagnosis-and-support-people-living-dementia (16 March 2015, date last accessed).

- 23. Merton R. Social Theory and Social Structure. New York: Free Press, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Melo G, Maroco J, de Mendonça A. Influence of personality on caregiver's burden, depression and distress related to the BPSD. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2011;26(12):1275–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Carter PA, Acton GJ. Personality and coping: predictors of depression and sleep problems among caregivers of individuals who have cancer. J Gerontol Nurs 2006;32(2):45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Garrosa E, Moreno-Jimenez B, Liang Y et al. The relationship between socio-demographic variables, job stressors, burnout, and hardy personality in nurses: an exploratory study. Int J Nurs Stud 2008;45(3):418–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Costa PT Jr., McCrae RR. ‘Set like plaster’: evidence for the stability of adult personality In: Heatherington T, Weinberger J (eds). Can Personality Change? Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1994:21–40. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fergus S, Zimmerman MA. Adolescent resilience: a framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Ann Rev Public Health 2005;26:399–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schoon I. Risk and Resilience: Adaptations in Changing Times. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dalkin SM, Greenhalgh J, Jones D et al. What's in a mechanism? Development of a key concept in realist evaluation. Implement Sci 2015;10(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mittelman MS, Haley WE, Clay OJ et al. Improving caregiver well-being delays nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2006;67(9):1592–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gallagher D, Ni Mhaolain A, Crosby L et al. Self-efficacy for managing dementia may protect against burden and depression in Alzheimer's caregivers. Aging Ment Health 2011;15(6):663–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hildon Z, Montgomery SM, Blane D et al. Examining resilience of quality of life in the face of health-related and psychosocial adversity at older ages: what is ‘right’ about the way we age. Gerontologist 2010;50(1):36–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maddi SR. Hardiness: the courage to grow from stresses. J Posit Psychol 2006;1(3):160–8. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Masten A. Ordinary magic: resilience processes in development. Am Psychol 2001;56(3):227–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. O'Dwyer ST, Moyle W, Zimmer-Gembeck M et al. Suicidal ideation in family carers of people with dementia: a pilot study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013;28(11):1182–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Payne S. Resilient carers and caregivers In: Monroe B, Oliviere D (eds). Resilience in Palliative Care – Achievement in Adversity. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007:83–97. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Farran CJ, Gilley DW, McCann JJ et al. Efficacy of behavioral interventions for dementia caregivers. West J Nurs Res 2007;29(8):944–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sorenson S, Duberstein P, Gill D et al. Dementia care: mental health effects, intervention strategies, and clinical implications. Lancet Neurol 2006;14:961–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nolan M, Ingram P, Watson R. Working with family carers of people with dementia ‘Negotiated'coping as an essential outcome. Dementia 2002;1(1):75–93. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Benbow SM, Ong YL, Black S et al. Narratives in a users’ and carers’ group: meanings and impact. Int Psychogeriatr 2009;21(1):33–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dowrick A, Southern A. Alzheimer's Society Report September 2014. Opportunity for Change. London: Alzheimer's Society Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Salfi J, Ploeg J, Black ME. Seeking to understand telephone support for dementia caregivers. West J Nurs Res 2005;27(6):701–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Milnac ME, Sheeran TH, Blissmer B et al. Resnick B, Gwyther LP, Roberto KA (eds). Resilience in Ageing: Concepts, Research & Outcomes. New York: Springer, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Egdell V. Development of support networks in informal dementia care: guided, organic, and chance routes through support. Can J Aging 2012;31(04):445–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Newbronner L, Chamberlain R, Borthwick R et al. A Road Less Rocky: Supporting Carers of People With Dementia. London: Carers Trust, 2013. Research Report. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012;380(9836):37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bandura A.. Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control. London: Macmillan, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bruvik FK, Ulstein ID, Ranhoff AH et al. The effect of coping on the burden in family carers of persons with dementia. Aging Ment Health 2013;17(8):973–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hepburn K, Lewis M, Tornatore J et al. The Savvy Caregiver program: the demonstrated effectiveness of a transportable dementia caregiver psychoeducation program. J Gerontol Nurs 2007;33:30–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Au A, Lai MK, Lau KM et al. Social support and well-being in dementia family caregivers: the mediating role of self- efficacy. Aging Ment Health 2009;13(5):761–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Snyder CR. The past and possible futures of hope. J Soc Clin Psychol 2000;19(1):11–28. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rustøen T, Cooper BA, Miaskowski C. A longitudinal study of the effects of a hope intervention on levels of hope and psychological distress in a community-based sample of oncology patients. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2010;15:351–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sun H, Tan Q, Fan G et al. Different effects of rumination on depression: key role of hope. Int J Ment Health Syst 2014;8(1):1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Piazza D, Holcombe J, Foote A et al. Hope, social support and self-esteem of patients with spinal cord injuries. J Neurosci Nurs 1991;23(4):224–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bays C. Older adults descriptions of hope after a stroke. Unpublished Doctoral dissertation. University of Cincinnati, Ohio, 1995.

- 57. Lohne V, Severinsson E. Hope during the first months after acute spinal cord injury. J Adv Nurs 2004;47(3):279–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Li R, Cooper C, Bradley J et al. Coping strategies and psychological morbidity in family carers of people with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2012;139:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Folkman S. Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Soc Sci Med 1997;45(8):1207–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Peel E. The living death of Alzheimer's versus ‘Take a walk to keep dementia at bay’: representations of dementia in print media and carer discourse. Sociol Health Illn 2014;36(6):885–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Suls J, David JP. Coping and personality: third time's the charm. J Pers 1996;64:993–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Aschbacher K, Patterson TL, von Känel R et al. Coping processes and hemostatic reactivity to acute stress in dementia caregivers. Psychosom Med 2005;67:964–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Simpson C, Carter P. Short-term changes in sleep, mastery & stress: impacts on depression and health in dementia caregivers. Geriatr Nurs (Minneap) 2013;34(6):509–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mehta M, Whyte E, Lenze E et al. Depressive symptoms in late life: associations with apathy, resilience and disability vary between young‐old and old‐old. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2008;23(3):238–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Downs M, Turner S, Bryans M et al. Effectiveness of educational interventions in improving detection and management of dementia in primary care: cluster randomised controlled study. Br Med J 2006;332(7543):692–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. The Carers Act. Gov. UK. 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/care-act-2014-part-1-factsheets/care-act-factsheets (15 October 2015, date last accessed).

- 67. Corbin J, Strauss A. Unending Work and Care: Managing Chronic Illness at Home. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Mukhopadhyay D, Mohanaruban K. Iron deficiency anaemia in older people: investigation, management and treatment. Age Ageing 2002;31(2):87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Alzheimer's Society. Fact Sheet: ‘Carers: Looking after Yourself’. 2015. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/documents_info.php?documentID=1 (11 November 2015, date last accessed).

- 70. Schindler M, Engel S, Rupprecht R. The impact of perceived knowledge of dementia on caregiver burden. GeroPsych 2012;25(3):127. [Google Scholar]

- 71. McAuley E, Katula J. Physical activity interventions in the elderly: influence on physical health and psychological function. Ann Rev Gerontol Geriatr 1998;18(1):111–54. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Schoenmakers B, Buntinx F, Delepeleire J. Factors determining the impact of care-giving on caregivers of elderly patients with dementia. A systematic literature review. Maturitas 2010;66(2):191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Clark PG, Blissmer BJ, Greene GW et al. Maintaining exercise and healthful eating in older adults: the SENIOR project II: Study design and methodology. Contemp Clin Trials 2011;32(1):129–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Qureshi H, Bamford C, Nicholas E et al. Outcomes in Social Care Practice: Developing an Outcome Focus in Care Management and Use Surveys. York: Social Policy Research Unit, University of York, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Takai M, Takahashi M, Iwamitsu Y et al. The experience of burnout among home caregivers of patients with dementia: Relations to depression and quality of life. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2009;49(1):e1–e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Cohen CA, Gold DP, Shulman KI et al. Positive aspects of caregiving: an overlooked variable in research. Can J Aging 1994;13:378–91. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Pinquart M. Age differences in perceived positive affect, negative affect, and affect balance in middle and old age. J Happiness Stud 2001;2(4):375–405. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Carstensen LL, Isaacowitz DM, Charles ST. Taking time seriously: a theory of socioemotional selectivity. Am Psychol 1999;54(3):165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Etters L, Goodall D, Harrison BE. Caregiver burden among dementia patient caregivers: a review of the literature. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2008;20(8):423–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Hilgeman M, Allen R, DeCoster J et al. Positive aspects of caregiving as a moderator of treatment outcome over 12 months. Psychol Aging 2007;22:361–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Nolan M, Lundh U. Satisfactions and coping strategies of family carers. Br J Community Nurs 1999;4(9):470–5. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Noonan AE, Tennstedt SL, Rebelsky FG. Making the best of it: themes of meaning among informal caregivers to the elderly. J Aging Stud 1996;10:313–27. [Google Scholar]

- 83. Diener E, Suh E. Measuring quality of life: economic, social, and subjective indicators. Soc Indic Res 1997;4:189–216. [Google Scholar]

- 84. Farran CJ, Keane-Hagerty E, Salloway S et al. Finding meaning: an alternative paradigm for Alzheimer's disease family caregivers. Gerontologist 1991;31(4):483–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Heisel MJ, Flett GL. Psychological resilience to suicide ideation among older adults. Clin Gerontol 2008;31(4):51–70. [Google Scholar]

- 86. Eagar K, Owen A, Williams K et al. Effective Caring: a Synthesis of the International Evidence on Carer Needs and Interventions; Vol. 1 and 2 University of Wollongong: Centre for Health Service Development, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Charlesworth G, Shepstone L, Wilson E et al. Does befriending by trained lay workers improve psychological well-being and quality of life for carers of people with dementia, and at what cost? A randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Assess (Rockv) 2008;12(4):314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Argimon JM, Limon E, Vila J et al. Health-related quality of life in carers of patients with dementia. Fam Pract 2004;21(4):454–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Yeandle S, Wigfield A (eds). Training and Supporting Carers: The National Evaluation of the Caring with Confidence Programme. Leeds, CIRCLE: University of Leeds, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 90. Daly L, McCarron M, Higgins A et al. ‘Sustaining Place’–a grounded theory of how informal carers of people with dementia manage alterations to relationships within their social worlds. J Clin Nurs 2013;22(3–4):501–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Barnes M, Henwood F, Smith N, Waller D. External Evaluation of the Alzheimer's Society Carer Information and Support Programme (CrISP). Brighton: University of Brighton Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 92. Cheng ST, Lam LC, Kwok T et al. Self-efficacy is associated with less burden and more gains from behavioral problems of Alzheimer's disease in Hong Kong Chinese caregivers. Gerontologist 2013;53(1):71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Oken BS, Fonareva I, Haas M et al. Pilot controlled trial of mindfulness meditation and education for dementia caregivers. J Altern Complement Med 2010;16(10):1031–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Markut LA, Crane A. Dementia Caregivers Share Their Stories: A Support Group in a Book. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 95. Lightbody P, Gilhooly M. The continuing quest for predictions of breakdown of family care of elderly people with dementia In: Marshall M. (ed). State of the Art in Dementia Care. London: Centre for Policy on Ageing, 1997:211–6. [Google Scholar]

- 96. Earvolino-Ramirez M. Resilience: a concept analysis. Nurs Forum 2007;42(2):73–82. Blackwell Publishing. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev 2000;71(3):543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Kenyon G, Bohlmeijer E, Randall WL (eds). Storying Later Life: Issues, Investigations, and Interventions in Narrative Gerontology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 99. Huggins G, Whorisky M, Semple L et al. Focus on Dementia: Changing Minds, Improving Lives in Scotland Annual Report. August 2015 http://www.qihub.scot.nhs.uk/media/865790/interim%20report%20final%20for%20printing%2026%20aug%202015.pdf (October 2015, date last accessed).

- 100. Bennett KM. How to achieve resilience as an older widower: turning points or gradual change. Ageing Soc 2010;30(3):369. [Google Scholar]

- 101. World Health Organisation Measuring Quality of Life. Division of Mental Health & Prevention of Substance Abuse 1997. http://www.who.int/mental_health/media/68.pdf (April 2016, date last accessed).