1. Jumping in the pool

“I think that he is freer than I am. I think it comes to personality too,.. I think I’m more anxiety driven, you know… I feel like I’m positive, but I’m wary. I don’t know that he is wary. I think he’s ready to jump in the pool. And I’m like aaww oo man eehh.. ok I’ll jump in the pool. And he’s just like… let’s jump.”

The angst and apprehension expressed by this musician when describing his experience improvising brings to light the demands improvisation makes on a musician’s ability to negotiate the uncertainty that characterizes unstructured performance contexts. It is this lack of structure that is the source of its complexity, its unpredictable nature that makes it both a challenging subject of study as well as a useful example of the under-determination of most of human behaviors. Music improvisation is situated within a culture and tradition of musical performance whose genres, scales, chords, and motifs can provide guidance for navigating these unrehearsed exchanges. But even with these structural elements, improvisation is still capable of generating wonder and surprise in both performers and listeners. Take for example the transcription of a brief excerpt of the improvisation between two piano players provided in Figure 11. These musicians perform with an open-ended backing track, a rhythmic-less drone consisting of the pitches D and A. At the point where the score begins they have already been improvising for about two minutes, trading highly chromatic, rapidly moving lines. As Player 1 is finishing a descending line he reaches a slowing point, and in this brief rest the improvisation takes on new life. The players arrive at a sudden harmonic congruence (at measure 5) where at the same moment Player 2 lands on the major triad associated with the tonal center, Player 1 begins to outline notes of the triad mixed in with natural upper harmonic extensions. In this moment the musical quality shifts significantly where the chromatic tendencies that previously characterized the performance are now abandoned and the harmony remains rooted in D major for the remainder of the performance.

Figure 1.

Musical score of a selected excerpt of one of the improvised performances included in this study.

In attempting to understand how these musicians are able to coordinate this shift in musical expression, it is worth giving attention to the use of the word “land” to describe how Player 2 arrives at playing the harmonic triad. It might sound as if this harmonic transition was the result of some outside physical force, which by chance happened to coordinate with Player 1’s actions. But when considering what they are playing before this shift, there is nothing explicit in the musical structure that indicates this transition. And yet somehow they arrive there, and arrive there together, collectively moving the sound into a new space of musical expression. An analysis of the previous seconds, minutes, or hours of performance, or a detailed account of their musical education and performance history will not provide a definitive answer about how musicians “know” what to play—and when—in a particular performance. In the opening quote, for instance, the musician is not describing characteristics about himself and his co-performer that are specific to musical experiences; the “wariness” and the “free” nature of his co-performer shape their behavior in social contexts in general. Differences in training and performance history can make individuals very different musicians, but they are also very different people. And in instances of musical improvisation where the indeterminacy is much like that of everyday social interactions, what it is that makes the musicians different people can significantly contribute towards the performance dynamics that emerge.

A significant proportion of contemporary research in music performance has been focused on understanding what musical interaction can tell us about human interaction in general (D’Ausilio et al., 2015; Moran, 2014; Sawyer, 2003), specifically empathy and its relationship to musical production and perception (Clarke, DeNora & Vuoskoski, 2015; Greenberg, Rentfrow, and Baren-Cohen, 2015; Krueger, 2013; Rabinowitch, 2015; Sevdalis & Keller, 2012). A few researchers have developed unique methods that explore social abilities within improvisatory coordination (Novembre et al., 2015; Hart et al. 2014; Noy 2014) where leader and follower roles are allowed to emerge and develop spontaneously within the task constraints. Music improvisation in particular lends itself to the examination of social connection, where in producing a cohesive performance players must listen and respond to each other’s musical actions. Communication between performers is often understood to entail the abstraction of musical production into representational imagery (Keller, 2008, Keller & Appel, 2010), but in the case of improvisation this communication is also considered to be specified in the movement dynamics of performers (Walton, Chemero & Richardson, 2014). When playing without the guide of musical notation, the ongoing movements of musicians operate to construct and constrain the flow of the performance from moment-to-moment (Walton, 2016).

Current research has also focused on how “embodied” musical performance is, or the extent to which body movement is a primary constituent of musical knowledge (Maes 2016; Maes et al., 2014; Leman & Maes, 2014; Geeves & Sutton, 2014). However, discussion about whether motor processes are “effects”, “mediators” or “causes”, doesn’t necessarily contribute to the understanding of how individuals actually engage in such a skill. Take the famous anecdote of Herbie Hancock recalling a performance with Miles Davis where he thought he played a “wrong note”, and Davis responded in such a way that “made it right”– inspiring Brian Eno’s oblique strategy: “honor your mistake as a hidden intention”. The point here is not whether or not the musical action was a mistake or an intentional act, but that in the context of improvisation performers have the choice to treat it as either. Accordingly, rather than simply exploring the self-evident fact that musical performance is embodied, one should explore how the different environmental constraints and information available shapes the behavior that emerges, where movements are part of the continuous information available to performers in guiding their musical actions. Indeed, listening and responding requires the physical movements of each player’s musical production to continuously anticipate and adapt to those of their co-performer’s, and so the music is in fact constituted by the self-organized dynamics of bodily coordination that emerge from this process (Borgo, 2005; Linson & Clarke, in press; Walton et al., 2015). We call the empathy that enables this sort of skillful, unreflective, improvised coordination ‘sensorimotor empathy’ (Chemero, 2016) to differentiate it from the explicit theorizing or simulation of the mental states of others (Gallese 2001; Steuber 2006). Here the act of musicians allowing their musical expression to be constrained by their co-performers takes the social, communicative, and even aesthetic component of improvisation and grounds it in the body.

The experiments described in this paper examine the coordination that emerges when skillful jazz musicians “jump in the pool” together. This takes on the challenge of understanding these spontaneous embodied musical exchanges, by applying and expanding upon nonlinear methods of dynamical systems to quantify the coordination that emerges between improvising musicians. These methods have proven their ability to reveal new structure within the complexity of music performance (Demos, Chaffin & Kant, 2014; Loehr, Large & Palmer, 2011, Maes et al., 2014) as well as pedagogy (Laroche & Kaddouch, 2015) and are particularly well suited for improvisation (Walton et al., 2015). Due to the open nature of improvised performances, it is difficult to make specific predictions about what exactly musicians will play and when. What these methods can reveal is how the dynamics of musician’s musical movements adapt in response to changes in the environment and the actions of co-performers, and provide insight into which kinds of dynamics result in more successful and creative performances. Accordingly, the first experiment applies these methods to examine the self-organized patterns of coordination between the bodily movements and musical expression that emerges between pairs of jazz pianists within the context of different performance constraints. Experiment 2 looks at how these patterns of coordination affect listener evaluations of the music being produced.

2. Freedom & constraint in music improvisation

2.1 Method

2.1.1 Participants

Six pairs of musicians were recruited from the local music community as well as the University of Cincinnati’s College-Conservatory of Music (CCM). The pairs had 8 to 46 years of training in piano performance (M = 19.7, SD = 12.5) and 4 to 46 years of experience with improvisation (M = 14.9, SD = 13.5) and ranged in age from 18 to 59 years (M = 30.4, SD = 14.3).

2.1.2 Procedure and Design

Participants played standing with an Alesis Q88, 88-key semi-weighted USB/MIDI keyboard controller, directly facing one another while their movements were recorded using a Latus Polhemus, wireless motion tracking system (at 96 Hz), see Figure 2. Participants were equipped with motion sensors attached to their forehead, and both their left and right forearms (positioned on the forearm directly above the point where the wrist bends). Ableton Live 9.0.5 was used to record all of the MIDI key presses and the resulting audio signal during the musical improvisation. Pairs were instructed to develop 2-minute improvised duets under vision and no-vision conditions, over different backing tracks. The vision and no-vision manipulation simply involved placing a curtain between musicians for half of the performances.

Figure 2.

Musicians performed improvised duets while their head, left arm, and right arm movements were recorded as well as the music produced on 88-key MIDI keyboards.

Musicians improvised with two different backing tracks: a swing and a drone backing track2. The swing backing track was the bass line of a chord progression from the jazz standard used by Keller, Weber and Engel (2011), titled: “There’s No Greater Love”. This track has a key and time signature (4/4), with the chord changes played on loop in an octave lower than that typically used. Finally, the drone backing track was a pair of pitches, D and A, that were played for the entire duration of the two minutes. While both of the tracks reference certain genres of music, drones being essential to the harmonic base of traditional Indian classical music, and the chord progression of the swing track highly characteristic of performing any jazz standard, the latter was most likely a more prominent part of most of the musicians’ training. Because drones aren’t used in jazz as often, the swing backing track (i.e., chord progression of a jazz standard) was more characteristic of their previous performance experiences.

At the beginning of the experiment, the musicians first performed two individual warm-up trials, where they improvised once over each backing track while their co-participant sat outside the performance room. Then together the pairs performed two blocks of four, two-minute improvised duets for a total of eight duets (2 conditions × 2 backing tracks × 2 blocks). After the musicians completed all of the improvisational trials they each were interviewed separately. During these interviews the video and audio from the last block of trials was played back using a laptop computer. The interview method used was an adaptation of that used by Norgaard (2011). The following was be read by the experimenter before the interview:

As you are watching and listening to your performance, try to narrate your conscious thinking, considering questions like, “Where did that come from?” We are looking for a narration similar to a director’s commentary on a DVD. We are particularly interested in how you are able to play with the backing track as well as with your co-performer. We are also interested in your creative process. How are you making decisions about what to play and when in your improvisation?

As the musicians watched the videos of their performances, the experimenters asked follow-up questions to explore and clarify points, as well as probed on interesting themes that emerged in their descriptions (Charmaz, 2006).

2.1.3 Analyses

The coordination that emerged between the improvising musicians with respect to their body movements and their musical production was analyzed using cross recurrence quantification analysis (CRQA). CRQA is a non-linear analysis method that quantifies the dynamic (time-evolving) similarity between two behaviors by identifying whether behavioral states in the two series reoccur over time (Marwan, 2008; Webber & Zbilut, 1992; 1994). Defined at a more intuitive level, CRQA assesses whether the points in behavioral event-series visit the same states over time and then quantifies the dynamic patterns of these time-evolving recurrences using a range of different statistics. Here we report the two most commonly employed statistics: Percent Recurrence (%REC), which measures the percentage of recurrent points between two behavioral time- or event-series, indexing the amount of shared activity between the two behavioral systems; and MaxLine: which corresponds to the length of the longest sequence of recurrent states observed between two behavioral time- or event-series, indirectly indexing the strength of the localized state coupling (manifested as repeated state sequences or behavioral trajectories) that exists between the two behavioral systems (Richardson et al., 2007). CRQA has been used to examine the nonlinear dynamics of numerous forms of interpersonal coordination, including rhythmic interpersonal synchrony (Richardson, Marsh & Schmidt, 2008; Richardson et al., 2005), the postural entrainment of conversing individuals (Shockley, Santana & Fowler, 2003; Shockley, 2005), and interpersonal timing behavior (Coey, Washburn & Richardson, 2014), as well as the non-stationary coordination of gestural activity and verbal communication between adults and infants and their caregivers (e.g., Dale & Spivey, 2005; Dale & Spivey, 2006; Fusaroli, Rączaszek-Leonardi & Tylén, 2014; Romero et al., 2016). This strengths of this analysis are that it does not require any a priori assumptions about the structure or stationarity of the data being analyzed, making it particularly appropriate for quantifying the fluctuations of improvised musical production. Also it can be applied to wide range of different types of time series, as Webber and Zbilut (2005) explain: if it “wiggles in time (physiology) or space (anatomy)”, recurrence analysis can quantify it (p. 81). And so both the dynamics inter-musician movement coordination and as well as playing behavior can be evaluated with CRQA, allowing one to measure the changes in both the musical structure (i.e., notes) as well as the interpersonal motor coordination using the same analysis metrics.

Cross Recurrence Quantification Analysis of Notes

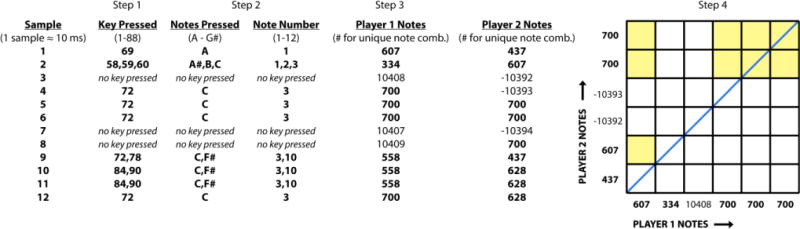

MIDI output provided the number of each key (from 1 to 88) as well as the on and off time for each key pressed. This was used to create an event series for each player that captured what notes and/or combinations of notes they pressed for each time point in the performance. Each key pressed was first assigned a number 1-12 representing the note of that key (A, A#, B, C#, etc.) so that a key press for a given note would be considered recurrent if the same note was repeated, regardless of the octave. Then the total number of unique combinations of notes pressed by both players was determined and each was assigned a code number. This code number was then substituted for the note or note combination it represented in order to generate a time series of code numbers for each player (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Timing of the playing behavior was preserved by using non-repeating random numbers to represent points in the performance when no keys were being pressed. Because CRQA is used to examine patterns that recur within a time series, non-repeating random numbers instead of zeros assured that “non-playing” moments were not quantified as recurrent states. While these “non-playing” moments are just as important to musical composition, this analysis focused specifically on how musicians coordinate the harmonic component of their playing behavior.

Figure 3.

The MIDI output of one player from Ableton provided information about the keys musicians pressed, as well as the duration of each key pressed, at a resolution of 96 Hz. Step 1 shows how a time series was generated that captured the number of each key pressed at each time point, as well as when there were no keys pressed. In Step 2 the note of each key is identified and assigned a number 1-12 such that a “C” was considered the same note regardless of which octave it was played in. Step 3 demonstrates how a code number was then generated for each unique combination of notes pressed. Time is preserved in the time series by inserting a non-repeating random number for time points where no key was pressed. The random numbers in Player 1 times series are positive, the random numbers in Player 2’s time series are negative, to assure that they don’t count as recurrent points. Then Steps 1-3 are repeated for the MIDI output of the second player, with the same set of code numbers used to identify notes and combination of notes played. The two time series are plotted against each other to identify when the musicians repeated each other’s musical states. This captures when musicians play the exact same thing at the same time (when a yellow recurrent point falls on the blue diagonal line), but more importantly when they repeat each other’s notes later in the performance (as when Player 2 repeats the note combination “700” after Player 1).

Figure 4.

The illustration of a portion of the recurrence plot from Figure 3 in relation to the actual recurrence plot from the full performance. %REC is calculated according to the percentage of “light blue” in the recurrence plot, MaxLine represents the length of the longest diagonal line of light blue points on the plot.

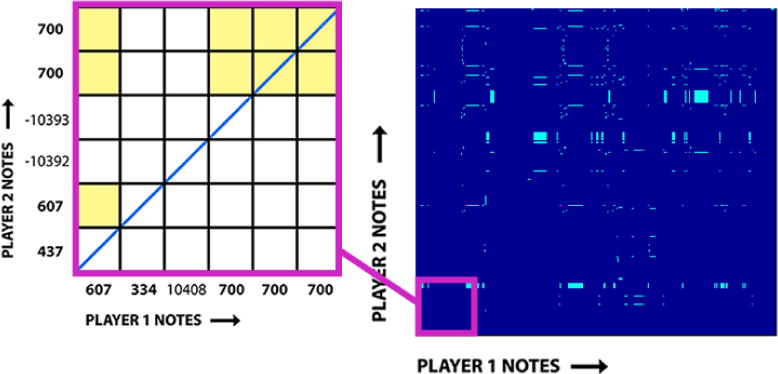

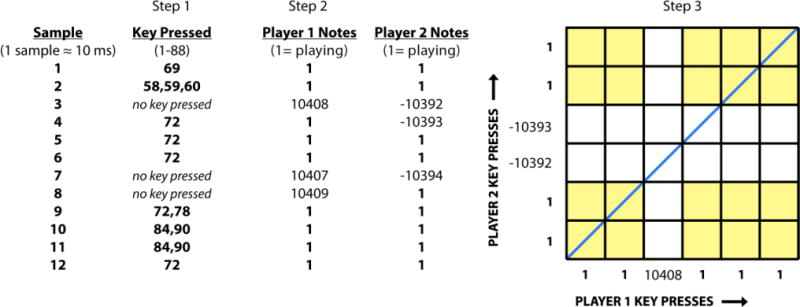

Cross Recurrence Quantification Analysis of Key Press Timing

In order to capture a more general measure of the rhythmic similarity in the timing of the musicians’ playing behavior, an event series was created for each player that represented the timing of their key presses. If any key or keys were pressed at a given time point, that time point was given the value of “1”, for illustration see Figure 5. If a key wasn’t being pressed it was assigned a random number so that it would not be quantified as a recurrent point as described above. Therefore recurrence in this case demonstrates more broadly when the musicians were pressing keys with the same temporal pattern, regardless of which keys were pressed. This analysis was meant to capture the complexity in how musicians repeat specifically the temporal aspect of each other’s playing sequences, often not repeating each other’s exact notes but transposing riffs or repeating “shapes”. It can also capture how left hands are engaged in “comping”, or synchronizing behavior in order to create a rhythmic foundation for the performance (note that the squares along the main diagonal indicated in blue on the cross-recurrence plot correspond to completely synchronous playing behavior).

Figure 5.

For key press timing the same MIDI output is used for each player, except in Step 1 any instance of any key or combination of keys being played is given a “1” in the time series, and an instance where nothing was played is assigned a random number. The random numbers in Player 1 times series are positive, the random numbers in Player 2’s time series are negative, to assure that they don’t count as recurrent points.

Cross Recurrence Quantification Analysis of Movement

Continuous CRQA was performed on the side-side movements of the musicians’ heads, left arms, and right arms that were captured using the Polhemus wireless motion sensors3. Continuous CRQA has been used in the authors’ previous work to quantify coordination in interpersonal oscillatory limb movements (Richardson et al., 2008; 2015). It differs from the categorical CRQA used to assess musical coordination in the MIDI data in that it determines the degree of recurrent activity using a method called phase space reconstruction. For a detailed explanation and examples of the application of this method see Webber & Zbilut (2005) and Richardson et al. (2008).

2.2 Results

A repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess differences in coordination (i.e., in notes, key press timing, and body movements) when the musicians improvised with the swing versus drone backing track. Because pairs performed in each experimental condition twice, the coordination measures for these trials were averaged for each of the six pairs and submitted to 2 × 2 ANOVAs that included both the backing track (swing/drone) and the vision manipulation (vision/no vision). Because there were no significant main effects of vision, nor any interaction effects of vision and backing track, only the main effects of backing track are reported.

2.2.1 Coordination in the musicians’ playing behavior

The results of the CRQA for coordination in the musicians’ playing behavior are summarized in Table 1. For the combination of notes played by the musicians, there was no significant main effect of backing track for %REC, F(1,5) = 4.41, p = .098, ηp2= .543, but there was for MaxLine, F(1,5) = 6.61, p = .050, ηp2= .569, where musicians repeated each other’s note combinations in significantly longer sequences when improvising with the drone backing track compared to the swing backing track. For key press timing there was also a significant effect of backing track on %REC, F(1,5) = 1561, p = .011, ηp2= .757, as well as MaxLine, F(1,5) = 14.81, p = .012, ηp2= .718, where musicians repeated each other’s key press timing more and in longer sequences when performing with the drone backing track compared to when performing with the swing backing track.

Table 1.

Results of CRQA for both the notes/combination of notes played as well as key press timing.

| Cross Recurrence Measure | df | F | p | ηp2 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Note(s) % REC | 5 | 04.14 | .098 | .543 | Drone: | 2.37* | 1.06 |

| Swing: | 1.21* | 0.48 | |||||

| Note(s) MaxLine | 5 | 06.61 | .050* | .569 | Drone: | 379.17 | 178.40 |

| Swing: | 120.44 | 77.77 | |||||

| Key Press Timing %RFC | 5 | 15.61 | .011* | .757 | Drone: | 42.62 | 9.74 |

| Swing: | 25.13 | 7.01 | |||||

| Key Press Timing MaxLine | 5 | 14.81 | .012* | .718 | Drone: | 1457 | 535.53 |

| Swing: | 596 | 333.14 |

2.2.2 Coordination in the musicians’ movements

Continuous CRQA was used to evaluate the coordination that emerged in the side-to-side movements of the musicians’ heads, left arms and right arms. Again, for clarity, the results are summarized in Table 2. For %REC of the musicians’ head movements there was no difference across backing tracks F(1,5) = 5.89, p = .060, ηp2= .541. However, MaxLine was significantly higher for the drone track F(1,5) = 6.56, p = .051, ηp2= .568, indicating that the musicians repeated each other’s head movement sequences more often when improvising with the drone compared to the swing track. The musicians’ left arm movements were also more recurrent with each other when performing with the drone track, such that there was a significant effect of backing track for %REC F(1,5) = 22.90, p = .005, ηp2= .821, as well as for MaxLine F(1,5) = 43.59, p = .001, ηp2= .897. There was also a main effect of backing track for %REC for the right arm movements F(1,5) = 30.55, p = .003, ηp2= .859, with more recurrence observed when improvising with the drone backing track compared to the swing backing track. Finally, there was an effect of backing track for right arm MaxLine F(1,5) = 14.07, p = .013, ηp2= .738, with longer sequences of recurrent activity in the movement of the musician’s right arms when improvising with the drone backing track.

Table 2.

Results of CRQA for on the musicians’ head, left arm, and right arm movements.

| Cross Recurrence Measure | df | F | p | ηp2 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head Side-to-side %REC | 5 | 05.89 | .060 | .541 | Drone: | 1.43 | 0.49 |

| Swing: | 0.89 | 0.77 | |||||

| Head Side-to-side MaxLine | 5 | 06.56 | .051 | .568 | Drone: | 405.96 | 85.23 |

| Swing: | 310.92 | 104.41 | |||||

| LArm Side-to-side %REC | 5 | 22.90 | .005* | .821 | Drone: | 2.94 | 1.83 |

| Swing: | 1.01 | 0.83 | |||||

| LArm Side-to-side MaxLine | 5 | 43.59 | .001** | .897 | Drone: | 5177.42 | 1818.94 |

| Swing: | 3508.02 | 1763.97 | |||||

| RArm Side-to-side %REC | 5 | 30.55 | .003* | .859 | Drone: | 1.49 | 0.58 |

| Swing: | 0.50 | 0.17 | |||||

| RArm Side-to-side MaxLine | 5 | 14.07 | .013* | .738 | Drone: | 5507.67 | 2073.37 |

| Swing: | 4781.79 | 1561.41 |

2.2.3 Surrogate Analysis

A surrogate analysis was performed to evaluate how much of the coordination was the result of musicians interacting with each other in real time, as opposed to coordination that would be expected from two musicians performing with the same backing track. To do so, “virtual” pairs were created where the time series of each player was matched up with the time series of players from other musician pairs. They were matched such that each virtual pair was made up of time series from players performing in in the same block, condition, and with the same backing track. The same CRQA analysis that was run on the real pairs was used to analyze these virtual pairs and the resulting measures were averaged. This average represented the amount of coordination to be expected between two musicians’ playing behavior just by virtue of doing the same task, in the same block, under the same vision conditions, and playing with the same backing track. Note that such coordination does not correspond to chance coordination per say, but rather reflects the degree to which the musical coordination observed between improvising musicians is defined and constrained by a particular backing track. A 2 × 2 × 2 with ANOVA, with pair type (real vs. virtual) in addition to backing track and condition was used to evaluate significant differences between the average coordination found in the virtual pairs and coordination between the real pairs (same values as used in the analyses above). While the effects of backing track for the virtual pairs were consistent with those for the real pairs (more coordination when playing with the drone), there were no significant interactions between pair type and backing track or condition. The results of the surrogate analysis are displayed in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

Results of surrogate analysis for CRQA on the musicians’ playing.

| Cross Recurrence Measure | df | F | p | ηp2 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Note(s) %RLC | 1 | 105.7 | .000* | .955 | Real: | 1.79 | 0.14 |

| Virtual: | 0.41 | 0.02 | |||||

| Note(s) MaxLine | 1 | 34.02 | .002* | .872 | Real: | 315.77 | 29.38 |

| Virtual: | 164.83 | 5.55 | |||||

| Key Press Timing %REC | 1 | .065 | .810 | .013 | Real: | 33.87 | 2.66 |

| Virtual: | 33.47 | 1.07 | |||||

| Key Press Timing MaxLine | 1 | .006 | .994 | .001 | Real: | 1027 | 119 |

| Virtual: | 1019 | 38 |

Table 4.

Results of surrogate analysis for CRQA on the musicians’ movements

| Cross Recurrence Measure | df | F | p | ηp2 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head Side-to-side %REC | 1 | .774 | .419 | .134 | Real: | 1.16 | 0.23 |

| Virtual: | 1.34 | 0.54 | |||||

| Head Side-to-side MaxLine | 1 | .334 | .588 | .063 | Real: | 358.44 | 28.73 |

| Virtual: | 373.16 | 9.77 | |||||

| LArm Side-to-side %REC | 1 | 4.85 | .079 | .492 | Real: | 1.60 | .287 |

| Virtual: | 1.080.89 | ||||||

| LArm Side-to-side MaxLine | 1 | .245 | .642 | .047 | Real: | 398.79 | 65.75 |

| Virtual | 371.05 | 14.65 | |||||

| RArm Side-to-side %REC | 1 | 23.27 | .005* | .823 | Real: | 1.20 | 0.58 |

| Virtual: | 1.67 | 0.84 | |||||

| RArm Side-to-side MaxLine | 1 | 6.23 | .005 | .555 | Real: | 354.13 | 14.43 |

| Virtual: | 404.02 | 13.69 |

The results from the surrogate analysis of the playing behavior reveal that for the key press timing, there were no significant differences between real and virtual pairs for %REC, F(1,5) = .065, p = .810, ηp2= .013 or Maxline, F(1,5) = .006, p = .994, ηp2= .001. However, real pairs showed significantly more coordination in the notes they played when compared with the virtual pairs, for %REC F(1,5) = 105.7, p = .000, ηp2= .955 and MaxLine F(1,5) = 34.02, p = .002, ηp2= .872. The key press timing measure therefore must capture coordination that is driven primarily by the structure of the backing track, where the coordination of musical expression is dependent upon real time interaction between performers.

When comparing differences in movement coordination between real and virtual pairs, overall there was not a significant difference. However there was one significant difference for %REC in right arm movement, F(1,5) = 23.27, p = .005, ηp2= .823, where there was also a significant interaction between pair type and backing track F(1,5) = 19.08, p = .007, ηp2= .792. Post-hoc analyses of the interaction between pair type and backing track revealed this difference was only significant for when the musicians were performing with the drone backing track. Interestingly, the significant difference in the movements of the right arm showed an opposite direction of effect when compared to the musical CRQA, specifically for the less structured performance context. It is important to note that while the movements of the right and left arm are distinguishable in the analysis of movement coordination, the MIDI data does not specify which hand played which keys. In trying to understand these results one could speculate that the musicians would be less coordinated in their right arm movements because they were attempting to play melodic lines that weren’t highly synchronized, but more complementary to their co-performer. This may have occurred exclusively when they were improvising with the drone backing track because unlike the swing backing track it didn’t provide guidance or precedent for when and how they should take turns playing melodic leads (i.e. “trading fours” in jazz performance). Overall all, clearer interpretation of these results would be facilitated by further application of these recurrence methods to a wider range of musical performance contexts.

2.3 Discussion

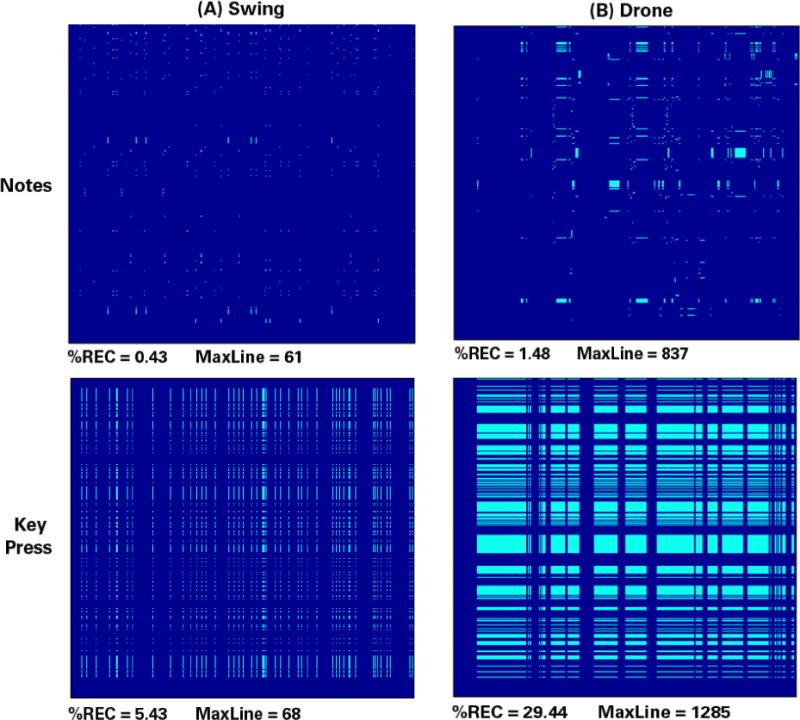

The measures used above to quantify coordination, even though taking into consideration the notes played by the performers, are still far from capturing all of the complexities of coordination inherent to musical expression. But even in the case that there are infinite ways musicians can respond to each other in the pitches, chords and timbre afforded by their instrument, these responses are still situated within patterns of synchronization and coordination. It is this coordination, this initial commitment to cooperation, that then allows for the performers’ individual natures to interact in ways that can significantly expand the musical possibilities. The CRQA results for both the movement and musical coordination that emerged between musicians indicates that the musicians’ playing behavior was harmonically and rhythmically more similar when improvising with the drone compared to when they were playing with the swing backing track, reflected by the increased coordination in both what the musicians played and how they moved together, see Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Example cross recurrence plots from a pair of musicians improvising with the swing backing track (column A) and the drone backing track (column B). The top row displays the CRQA plots and measures for the notes the musician’s played, the bottom row shows the recurrence between their key press patterns. Visual inspection of the amount of recurrence in these plots (i.e. the amount light blue) demonstrate how for the drone backing track musicians were significantly more coordinated in their musical expression.

These results are surprising when compared to the results of the qualitative analysis of the post-session interviews. These interviews were analyzed using grounded theory (Charmaz, 2006) using the NVivo software package, in order to identify higher-order themes in the musicians’ descriptions of their experiences improvising (for more details see Walton, 2016). While their playing was overall more similar and more coordinated for the drone, they reported experiencing more freedom in the performance. One player discussed the openness of the drone backing-track: “The options are pretty much endless with this one, there are less limitations with that one note going and you can kind of just build whatever you want”. Another musician explained how this lack of limitation provided space to more freely engage with his co-performer: “…because there wasn’t a lot of outside information to deal with, it allowed us to really interact with each other”. And yet another musician went further to say that this had a significant impact on the quality of the performance: “… playing with a backing track, there is no room to grow as a whole… it’s tough to tell a story. We did it best on the drone, where we started out with simple ideas and grew in dynamics, rhythm, and added different harmonies.” The lack of structure provided by the drone better supported exchange between the performers, and made it possible for musicians to work together to build their own unique musical narrative. Thus the cross recurrence analysis of both the musicians’ movement and musical coordination provided a way for quantifying the self-imposed structure in response to the lack of constraint of the drone backing track that would not be fully captured in verbal reports of the musicians’ experience.

The results here demonstrate the challenge in understanding the complex dynamics of interpersonal coordination, where understanding how these dynamics emerge from and interact with the structure of the behavioral context is key to understanding the system’s behavior. In this case different performance contexts required that certain relationships within the system be more constrained and synchronized, while other relationships be more complementary. Furthermore, the experiences of individuals engaging in this coordination had more to do with the way that they were able to co-create structure, and is relevant for considering how the environment supports the emergence of collaboration and novel behavior. Constraints are often understood according to how they limit possibility for action. But here we see an example of creative freedom engendered by constraint, where the drone track demanded a commitment to synchronization in order to maintain a common structure from which could emerge turn-taking dynamics that allowed the musician’s individuality to flourish. This study provides an example of how performance constraints can support collaborative dynamics in musical exchanges that are truly social. But these results in particular give an account of only the musicians’ experience of the performance constraints. Experiment 2 explores the relationship between the movement and musical coordination that emerged in these different contexts of social interaction and the quality of the music produced, or how this musical collaboration is experienced by listeners.

3. The sounds of music

3.1 Method

3.1.1 Participants

An initial sample of 61 participants from the University of Cincinnati’s participant pool were recruited to listen to recordings of the music produced by the improvising musicians. Listeners had an average of 3.2 years of musical experience, and 1.17 years experience improvising, but 46% of listeners had no musical experience at all, and 65% no experience improvising.

3.1.2 Method & Procedure

Surveys were programmed and administered through the Qualtrics web-based survey platform, hosted through an account licensed to the University of Cincinnati. The survey consisted of four two-minute songs, one from each condition: swing-no vision, swing-vision, drone-no vision, drone-vision. Thus, there were twenty-four different recordings used for the listener evaluations. The link to the survey was sent to participants through email, and they could fill out the survey anywhere from any device; their only instructions were to listen with headphones and listen to the recordings in their entirety. Participants would press play to listen to the recording, and when it finished playing they were able to navigate to the next page where they responded to three different statements about the recording using a 4-point Likert scale. The statements were listed as follows: “The musicians in this improvisation are coordinated”, “This improvisation is harmonious” and “I enjoyed listening to this improvisation”. There were no instructions provided to participants regarding the criteria they should use in evaluating the pieces according to these terms. As noted above most of the participants had little if any musical experience, let alone experience with musical evaluation, so it was not necessarily expected that each participant would base their rating on the same qualities of the music. The goal was to capture a more general attunement to whether a musical interaction is “coordinated”, referring to a more technical component of the music, “harmonious” which implicates the aesthetic qualities of the music, and “enjoyment” or personal preference for the music. Participants answered these questions for each of the four pieces, and at the end of the survey answered demographic questions that included their age, area of study, years of experience with music performance, and years of experience with improvisation.

3.1.3 Analyses

The amount of time spent on each page of the survey was recorded, and if the participant navigated to the next page without listening to the entire song, their data was eliminated. The remaining scores were then averaged across participants for each track. The Pearson’s r correlation coefficient was calculated to evaluate the relationships between these averaged listener ratings of “coordination” “harmony” and “enjoyment”, and the CRQA measures of the coordination in the musicians’ notes, key presses, head movements, left arm movements, and right arm movements for each recording.

3.2 Results

Table 3 displays correlations between the listener ratings and coordination of the musicians playing behavior, or how much the musicians repeated each other’s notes/combination of notes as well as overall key press timing. There were significant correlations between listener ratings and how much the musicians coordinated their key press timing when improvising with the drone track. Listeners rated performances with the drone as more harmonious when the MaxLine in the musicians’ key press timing was higher r(10) = .669, p = .017. There was also a positive correlation with key press timing, where the degree that listeners enjoyed the track was associated with a higher MaxLine in key press timing, r(10) = .632, p = .028.

There was also a relationship between the listener ratings and the movement coordination that emerged between the improvising musicians. Table 4 displays correlations between the listener ratings and head movement coordination, as measured by the %REC and MaxLine. For %REC there was a negative correlation between how “coordinated” the listeners rated a track and the coordination between the musicians’ head r(10) = −.602, p = .038 and left arm movements r(10) = −.617, p = .033. There was also a negative correlation between the musician’s left arm movement coordination and how “harmonious” the track was rated by listeners r(10) = −.676, p = .016. For how much the listeners reported enjoying listening to the performance, there was negative correlation between “enjoyment” and the coordination of the musicians’ head movements r(10) = −.625, p = .030.

3.3 Discussion

After examining how constraints on the dynamics of musical and movement coordination support collaboration between performers in Experiment 1, Experiment 2 aimed to identify how these dynamics might play a role in shaping the experience of listeners. With respect to how the coordination of the musician’s playing was related to the listener ratings, the results in Experiment 2 are interesting in light of the increased coordination for the drone track found in Experiment 1. In Experiment 1 there was more coordination in key press timing when the musicians were performing with the drone backing track, and in Experiment 2 how “harmonious” listeners rated the performance was significantly related to the length of the recurrent sequences in the musicians’ key press timing. This suggests that listeners may be attuned to the way the improvising musicians worked together to build the narrative of the performance. It also indicates that the perception of aesthetic harmoniousness is related to the rhythmic similarity captured by the key press timing.

With respect to the movement coordination that emerged between musicians, the negative correlations between left arm coordination and listener evaluation measures allude to the ways in which a successful improvised performance may be about how the coordination between musicians reflects complementary rather than purely synchronous behavior. For example there are positive correlations between the degree of recurrent structure of the musicians’ key press timing and listener ratings, but overall negative correlations between ratings and the degree of coordination in the musicians’ arm movements. This may indicate that the co-construction of musical expression, while involving similar rhythmic qualities of playing, requires more difference in movement across the keyboard as captured by the coordination in left arm movements. This provides a demonstration of the subtlety required to understand coordination in the unconstrained context of everyday interactions (Schmidt et al., 2014; 2016). Additionally, given that the listeners were only listening to the audio of the performance and not watching a video, it is interesting to find significant relationships in listener experience and musicians’ head movements. The head movement may be considered to have an indirect relationship to the dynamics of the music produced, but as indicated by these results may play an important role in the resulting temporal structure of an improvisation. This is consistent with previous work that has explored the contribution of head movement to expressivity in solo piano performance (Castellano et al., 2008, Sudnow, 1978), and in joint musical action might play a role in how co-performers communicate and establish a rhythm within performance.

In exploring auditory perception Clarke (2005) considers how listeners discover “what sounds are the sound of”. He makes the case that this discovery process when listening to music is not qualitatively different than when we perceive sounds in our everyday environment. Sounds provide information about events in our environment, often in relation to the motion of objects, ourselves, and others. Thus we develop a perceptual attunement, where sounds specify what is moving and happening around us. This relationship between sound and motion is also important to our experience of musical recordings. Listening to the radio or a CD is obviously a different case of musical engagement than going to a live concert, but the sounds of the recording still specify real events: the movements of the performers (Clarke, 2005). Additionally, Iyer (2002; 2004), Shove and Repp, (1995), Repp (1992) and Truslit (1938) have provided key initial explorations of the different ways that constraints on biological motion, whether it be of the limbs, breath, or the heart beat, relate to both the production and perception of the spatio-temporal properties of music.

The results presented here suggest that listeners respond to not only what part of the performer is moving, and how is it moving, but also how those movements relate to those of co-performers. That is, the events specified by sounds necessarily include not only movements of performers but also how performers are coordinating their movements together. In fact, examining music in relation to the action capabilities of individual bodies leaves out the majority of musical listening that involves hearing the coordination of many. When listening to a quartet, band, or orchestra, how the musicians collectively coordinate their musical movements is arguably the primary determinant of the quality of the musical experience. In the case of this study, it may be incorrect to say listeners “hear” the way the musicians are moving their heads. However, the results do seem to indicate that listeners are attuned to the way the head movements structure the dynamics that emerge and evolve across the timespan of the performance.

The fact that the musicians’ movements affected the experience of the music is also interesting in light of the question of who was listening. The listeners in this study were primarily non-expert musicians, with virtually no experience with music improvisation in particular. Lack of common musical education, previous experience, difference in perception of criteria, language, personal preference, and in this case even the listening environment are some of the many factors that introduce variability to how the listeners respond to a given piece of music at a given time. But while the importance of head movement coordination in this study will not always prove relevant to all listening experiences, it seems possible to identify how in different contexts the self-organized interactions of a system’s components gives rise to sounds that have certain meaning to listeners (“coordination, “enjoyment”, etc.).

When considering the importance of coordination to many of our experiences, it in fact isn’t surprising that interpersonal coordination would be an important part of our perceptual sensitivity to sounds. Phillip-Silvers and Keller (2012) argue that our ability to entrain with others and our environment begins at the very early stages of development, where at the “roots” of our ability to coordinate musically are more general turn-taking skills that involve anticipating and adapting to movements of those around us. Clarke (2005) claims that music has the power to induce the experience of musical “agents”. The results of the current study provide initial evidence for how the movement of those agents constitutes a common ground for our perception of music, where not only our engagement in musical production but also musical listening is rooted in our ability to coordinate with the world and others.

4. Making waves

We have seen, in Experiment 1, that skilled musicians playing along with one another and an unstructured backing track coordinate with one another more than when they are playing along with a structured backing track. From the post-session interviews, we also found that the performance context that brought about the increase in coordination created an increased opportunity for interpersonal connection and opportunity for creativity. We also found, in Experiment 2, that listeners can hear the patterns of coordination that musicians create together and that it influences their perceptions of aesthetic features of the recordings. Taken together then, the current results reveal how different constraints on improvisation shape the experience of musicians as well as the musical and movement dynamics that emerge (and are heard). Discovering performance contexts capable of successfully facilitating these dynamics is not about imposing structure on a performance, but how the context demands participants to co-determine that structure.

When describing his experience improvising with the drone backing track, one musician explains: “There’s no time, it’s just a steady tone, …we created time between us”. While a lot of research aims to understand the power in our ability to synchronize, or keep time together, when it comes to understanding music performance as a social interaction, it is more important how we create time together. Talking about how performers’ musical actions “overlap”, how they “fill in gaps” or “compensate” for one another is still considering them first as individual entities who then must find a way to co-exist through the coordination of their playing. But when musicians create time together, they are no longer behaving as individuals but as a single, collective unit – flexibly navigating the shared temporal landscape conceived by their musical actions (Laroche, Berardi & Brangier, 2014). Doing so requires sensorimotor empathy, the ability to skillfully and implicitly coordinate your actions with another person. We do this in everyday conversation (Richardson, Dale, & Marsh, 2014; Schmidt et al., 2012; 2014; Shockley, Richardson, & Dale 2009; Dale et al., 2013; Fusaroli et al., 2014), but it is more visible and more striking in a musical context. Collective musical improvisation demands openness and adaptation to maintain “group flow” (Hart & Di Blasi, 2013; Sawyer, 2006), and also an immense trust in the collective ability to build a foundation from which the performance will be developed, despite the possible wariness or anxiety that this may induce. But “mistakes” or “surprises” are defined by how their actions deviate in relationship to this foundation performers create together. And in the concession, adjustment, and opposition to this co-determined “time” is where each performer’s individuality, their different personalities create the possibility for something truly novel and unexpected.

The creation of time is about the creation of the beat, and the beat is felt physically with every key press, foot tap, breath, and head sway. Musicians’ movements define the structure and can also stretch, obscure or accentuate its parts, the minor but powerful temporal deviations from the force of the rhythm are considered to be the source of “groove” in music (Iyer, 2002; Janata, Tomic & Haberman, 2012; Pressing, 2002). Consider the positive correlation between the coordination of the musicians’ key press timing and how “harmonious” the performances were rated, as well as the negative correlation between head and left arm coordination and the “harmonious” ratings. It seems the physical rigor of creating this structure, and the ways musicians engage in the freedom to deviate from it, is salient to listeners. And while an expert examination of a musical score can provide information about harmonic congruence as demonstrated in the excerpt described in the introduction, what may be more universally relevant is how they negotiate the risks of taking these liberties. Whether it is characterized by excitement or hesitation, it is the manner in which the musicians “jump in the pool” that may be most essential to the meaning of music for listeners.

It might be difficult to conceive of how this force can be felt by listeners who are not actively engaged, or even present for the improvisational performance. Studies have looked at how music induces movement in listeners (Hurley, Martens & Janata, 2014; Ross et al., 2016; Stupacher, Hove & Janata, 2016; Van Dyck et al., 2013) but they are not bi-directionally coupled with performers and so cannot alter the evolution of the musical events. As discussed previously, however, their perception is rooted in their general ability to take part in this active engagement with their environment. And so when listening to the way that musicians take risks, adapt to and defy the beat, their perceptual sensitivity to the musical coordination allows them to follow alongside the performers, anticipating their musical choices (Huron, 2006) and experiencing anxiety and surprise as they succeed or fall flat.

The “sudden” harmonic congruence or surprising “mistakes” that result from these deviations and risks are a crucial part of how performers discover new musical spaces. As improvising musicians engage in sensorimotor empathy to co-create these spaces by “feeling-into” and “feeling-out” possibilities with their musical movements, this allows for the creation of new social spaces. Think about how music can “move” us. The driving force of a drum line in a military march, or the riots following Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring are some more literal examples that come to mind. But music is also capable of expanding our openness to unfamiliar social realms that initially make us cautious or uneasy. It can cultivate a willingness to inhabit these social spaces, if even for a brief moment of musical time, our will steadied by the universal familiarity of the rhythms of human motion. It is this common ground of the embodied aesthetic of musical collaboration that inspires the motion necessary to create new possibilities, and bigger waves.

Table 3.

Correlations with listener ratings and %REC and MaxLine fоr notes played and key press timing.

| %REC Survey Question (rated on a 4−point Likert scale) |

Swing | Drone | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Note(s) | Key Press | Note(s) | Key Press | ||

| The musicians in this improvisation are coordinated. | r | .423 | .231 | .243 | .487 |

| p | .171 | .471 | .446 | .109 | |

| This improvisation is harmonius. | r | .047 | .275 | −.167 | −.070 |

| p | .886 | .386 | .604 | .828 | |

| I enjoyed listening to this improvisation. | r | .034 | −.210 | .117 | .332 |

| p | .916 | .516 | .718 | .292 | |

|

MaxLine Surv ey Question (rated on a 4−point Likert scale) |

Swing | Drone | |||

| Note(s) | Key Press | Note(s) | Key Press | ||

|

| |||||

| The musicians in this improv isation are coordinated. | r | .325 | −.029 | −.204 | .501 |

| p | .303 | .930 | .525 | .097 | |

| This improvisation is harmonius. | r | −.230 | −.350 | −.041 | .669* |

| p | .472 | .264 | .900 | .017 | |

| I enjoyed listening to this improvisation. | r | −.188 | −.445 | −.088 | .632* |

| p | .559 | .147 | .787 | .028 | |

Table 4.

Correlations with listener ratings and %REC and MaxLine in the musicians’ head, left arm, and right arm movements.

| %REC Survey Question (rated on a 4−point Likert scale) |

Swing | Drone | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head | LArms | RArms | Head | LArms | RArms | ||

| The musicians in this improvisation are coordinated. | r | .024 | −.118 | .077 | −.602* | −.617* | −.364 |

| p | .941 | .715 | .812 | .038 | .033 | .245 | |

| This improvisation is harmonius. | r | .047 | −.157 | −.417 | −.561 | −.676* | −.481 |

| p | .886 | .626 | .177 | .058 | .016 | .113 | |

| I enjoyed listening to this improvisation. | r | −.400 | −.277 | −.349 | −.625* | −.519 | −.378 |

| p | .197 | .384 | .266 | .030 | .084 | .225 | |

|

MaxLine Survey Question (rated on a 4−point Likert scale) |

Swing | Drone | |||||

| Head | LArms | RArms | Head | LArms | RArms | ||

|

| |||||||

| The musicians in this improvisation are coordinated. | r | .061 | −.188 | .017 | −.474 | −.507 | .177 |

| p | .851 | .558 | .958 | .119 | .093 | .581 | |

| This improvisation is harmonius. | r | −.400 | −.369 | −.168 | −.536 | −.676* | −.117 |

| p | .197 | .237 | .602 | .072 | .016 | .716 | |

| I enjoyed listening to this improvisation. | r | −.471 | −.378 | −.391 | −.613* | −.617* | −.176 |

| p | .122 | .226 | .209 | .034 | .033 | .585 | |

Acknowledgments

The research presented was completed as part of the first authors Masters work (Walton, 2016). The research was also supported, in part, by funds from the National Institutes of Health (R01GM105045). The authors would like thank Dr. Michael Riley (University of Cincinnati), Dr. Charles Coey (College of the Holy Cross), and Dr. Richard C. Schmidt (College of the Holy Cross) for their support and for the helpful comments they provided in relation to this work. A special thanks to Adam Petersen and Josh Jessen for assistance in conceptualizing the study and composing the backing tracks, Ben Sloan for sound engineering, and Stephen Patota for transcribing the included excerpt.

Footnotes

The video for this excerpt can be viewed at: http://www.emadynamics.org/music-improvisation-video.

The musicians also improvised with an ostinato track in 7/8 time, but these results are omitted for this publication.

The phase space embedding time lag was 25 samples and 5 embedding dimensions, and a recurrence radius of 10% of the mean rescaled distance between points.

Contributor Information

Ashley E. Walton, Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, USA.

Peter Langland-Hassan, Department of Philosophy, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, USA.

Anthony Chemero, Department of Psychology, Department of Philosophy, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, USA.

Heidi Kloos, Department of Psychology, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, USA.

Michael J. Richardson, Department of Psychology and Perception in Action Research Centre, Faculty of Human Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Works Cited

- Borgo D. Sync or swarm: improvising music in a complex age. New York: The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano G, Mortillaro M, Camurri A, Volpe G, Scherer K. Automated analysis of body movement in emotionally expressive piano performances. Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 2008;26(2):103–119. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chemero A. Sensorimotor Empathy. Journal of Consciousness Studies. 2016;23(5–6):138–152. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke EF. Ways of listening: An ecological approach to the perception of musical meaning. Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke E, DeNora T, Vuoskoski J. Music, empathy and cultural understanding. Physics of life reviews. 2015;15:61–88. doi: 10.1016/j.plrev.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coey CA, Washburn A, Richardson MJ. Recurrence Quantification as an Analysis of Temporal Coordination with Complex Signals. In: Marwan N, Riley M, Giuliani A, Webber CL, editors. Translational Recurrences: From Mathematical Theory to Real-World Applications. Springer; International Publishing: 2014. pp. 173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Dale R, Fusaroli R, Duran N, Richardson DC. The self-organization of human interaction. Psychology of learning and motivation. 2013;59:43–95. [Google Scholar]

- Dale R, Spivey MJ. 27th Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2005. Categorical recurrence analysis of child language; pp. 530–535. [Google Scholar]

- Dale R, Spivey MJ. Unraveling the dyad: Using recurrence analysis to explore patterns of syntactic coordination between children and caregivers in conversation. Language Learning. 2006;56(3):391–430. [Google Scholar]

- Demos AP, Chaffin R, Kant V. Toward a dynamics theory of body movement in musical performance. Frontiers in Psychology. 2014;5(477):1–6. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusaroli R, Rączaszek-Leonardi J, Tylén K. Dialog as interpersonal synergy. New Ideas in Psychology. 2014;32:147–157. [Google Scholar]

- Gallese V. The ‘shared manifold’ hypothesis. From mirror neurons to empathy. Journal of consciousness studies. 2001;8(5–6):33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Geeves A, Sutton J. Embodied cognition, perception, and performance in music. Empirical Musicology Review. 2014;9:248–253. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg DM, Rentfrow PJ, Baron-Cohen S. Can music increase empathy? Interpreting musical experience through the empathizing–systemizing (ES) theory: Implications for Autism. Empirical Musicology Review. 2015;10(1–2):80–95. [Google Scholar]

- Hart Y, Noy L, Feniger-Schaal R, Mayo AE, Alon U. Individuality and togetherness in joint improvised motion. PloS one. 2014;9(2):e87213. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart E, Di Blasi Z. Combined flow in musical jam sessions: A pilot qualitative study. Psychology of Music. 2013 0305735613502374. [Google Scholar]

- Hurley BK, Martens PA, Janata P. Spontaneous sensorimotor coupling with multipart music. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2014;40(4):1679. doi: 10.1037/a0037154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huron DB. Sweet anticipation: Music and the psychology of expectation. MIT press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer V. Embodied Mind, Situated Cognition, and Expressive Microtiming in African-American Music. Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 2002;19:387–414. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer V. Uptown Conversations: the New Jazz Studies. New York: Columbia University Press; 2004. Exploding the Narrative in Jazz Improvisation; pp. 393–403. [Google Scholar]

- Janata P, Tomic ST, Haberman JM. Sensorimotor coupling in music and the psychology of the groove. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2012;141(1):54. doi: 10.1037/a0024208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller PE, Appel M. Individual differences, auditory imagery, and the coordination of body movements and sounds in musical ensembles. Music Perception. 2010;28:27–46. [Google Scholar]

- Keller PE. Joint action in music performance. In: Morganti F, Carassa A, Riva G, editors. Enacting intersubjectivity: A cognitive and social perspective to the study of interactions. Amsterdam: IOS Press; 2008. pp. 205–221. [Google Scholar]

- Keller PE, Weber A, Engel A. Practice makes too perfect: Fluctuations in loudness indicate spontaneity in musical improvisation. Music Perception. 2011;29:107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger J. Empathy, Enaction, and Shared Musical Experience. In: Cochrane T, Fantini B, Scherer K, editors. The Emotional Power of Music: Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Musical Expression, Arousal, and Social Control. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013. 2013. pp. 177–196. [Google Scholar]

- Laroche J, Berardi AM, Brangier E. Embodiment of intersubjective time: relational dynamics as attractors in the temporal coordination of interpersonal behaviors and experiences. 2014 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laroche J, Kaddouch I. Spontaneous preferences and core tastes: embodied musical personality and dynamics of interaction in a pedagogical method of improvisation. Frontiers in psychology. 2015;6 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leman Marc, Maes Pieter-Jan. The Role of Embodiment in the Perception of Music. Empirical Musicology Review. 2015;9(3–4):236–246. [Google Scholar]

- Linson A, Clarke EF. Distributed cognition, ecological theory, and group improvisation. In: Clarke E, Doffman M, editors. Distributed Creativity: Improvisation and Collaboration in Contemporary Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press; (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Loehr J, Large EW, Palmer C. Temporal coordination in music performance: Adaptation to tempo change. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2011;37(4):1292–1309. doi: 10.1037/a0023102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes PJ. Sensorimotor grounding of musical embodiment and the role of prediction: a review. Frontiers in psychology. 2016;7 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes PJ, Leman M, Palmer C, Wanderley M. Action-based effects on music perception. Frontiers in psychology. 2014;4:1008. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.01008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marwan N. A historical review of recurrence plots. European Physical Journal. 2008;164:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Moran N. Social implications arise in embodied music cognition research which can counter musicological “individualism”. Frontiers in psychology. 2014;5:676. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norgaard M. Descriptions of Improvisational thinking by Artist-Level Jazz Musicians. J Res Music Educ. 2011;59:109–127. doi: 10.1177/0022429411405669. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Novembre G, Varlet M, Muawiyath S, Stevens CJ, Keller PE. The E-music box: an empirical method for exploring the universal capacity for musical production and for social interaction through music. Royal Society open science. 2015;2(11):150286. doi: 10.1098/rsos.150286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noy L. The mirror game : a natural science study of togetherness. In: Citron A, Aronson-Lehavi S, Zerbib D, editors. Performance Studies in Motion. London: Bloomsbury Methuen Drama; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips-Silver J, Keller PE. Searching for roots of entrainment and joint action in early musical interactions. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2012;6:26. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pressing J. Black Atlantic rhythm: Its computational and transcultural foundations. Music Perception. 2002;19:285–310. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitch TC, Knafo-Noam A. Synchronous rhythmic interaction enhances children’s perceived similarity and closeness towards each other. PloS one. 2015;10(4):e0120878. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repp BH. Music as Motion: A Synopsis of Alexander Truslit’s 1938 “Gestaltung und Bewegung in der Musik”. Haskins Laboratories Status Report on Speech Research. 1992:265–278. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson MJ, Harrison SJ, Kallen RW, Walton A, Eiler B, Schmidt RC. Self-Organized Complementary Coordination: Dynamics of an Interpersonal Collision-Avoidance Task. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2015;41:665–79. doi: 10.1037/xhp0000041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson MJ, Dale R, Marsh KL. Complex Dynamical Systems in Social and Personality Psychology: Theory, Modeling and Analysis. In: Reis HT, Judd CM, editors. Handbook of Research Methods in Social and Personality Psychology. 2nd. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson MJ, Lopresti-Goodman S, Mancini M, Kay BA, Schmidt RC. Comparing the attractor strength of intra- and interpersonal interlimb coordination using cross recurrence analysis. Neuroscience Letters. 2008;438:340–345. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.04.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson MJ, Marsh KL, Schmidt RC. Effects of visual and verbal information on unintentional interpersonal coordination. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2005;31:62–79. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.31.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero V, Fitzpatrick P, Schmidt RC, Richardson MJ. Using Cross-Recurrence Quantification Analysis to Understand Social Motor Coordination in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. In: Webber CL Jr, et al., editors. Recurrence Plots and Their Quantifications: Expanding Horizons, Springer Proceedings in Physics 180. Switzerland: Springer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ross JM, Warlaumont AS, Abney DH, Rigoli LM, Balasubramaniam R. Influence of musical groove on postural sway. 2016 doi: 10.1037/xhp0000198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer RK. Group-creativity: musical performance and collaboration. Psychology of Music. 2006;34:148–165. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer RK. Group Creativity: Music, Theatre, Collaboration. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt RC, Morr S, Fitzpatrick P, Richardson MJ. Measuring the dynamics of interactional synchrony. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 2012;36:263–279. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt RC, Nie L, Franco A, Richardson MJ. Bodily synchronization underlying joke telling. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2014 doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevdalis V, Keller PE. Perceiving bodies in motion: expression intensity, empathy, and experience. Experimental Brain Research. 2012;222:447–453. doi: 10.1007/s00221-012-3229-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shockley K. Cross recurrence quantification of interpersonal postural activity. Tutorials in contemporary nonlinear methods for the behavioral sciences. 2005:142–177. [Google Scholar]

- Shockley K, Santana MV, Fowler CA. Mutual interpersonal postural constraints are involved in cooperative conversation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2003;29:326–332. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.29.2.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shockley K, Richardson DC, Dale R. Conversation and coordinative structures. Topics in Cognitive Science. 2009;1(2):305–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-8765.2009.01021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shove P, Repp BH. Musical motion and performance: theoretical and empirical perspectives. In: Rink J, editor. The Practice of Performance. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press; 1995. pp. 55–82. [Google Scholar]

- Stueber KR. Rediscovering empathy: Agency, folk psychology, and the human sciences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stupacher J, Hove MJ, Janata P. Audio features underlying perceived groove and sensorimotor synchronization in music. Music Perception. 2016;33(5):571–589. [Google Scholar]

- Sudnow D. Ways of the Hand. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Truslit A. Gestaltung und Bewegung in der Musik. Berlin: Chr. Friedrich Vieweg; 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyck E, Moelants D, Demey M, Deweppe A, Coussement P, Leman M. The impact of the bass drum on human dance movement. Music Perception. 2013;30:349–359. [Google Scholar]

- Walton A, Richardson MJ, Chemero A. Self-organization and Semiosis in Jazz Improvisation. International Journal on Signs and Semiotics Systems 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Walton A, Richardson MJ, Langland-Hassan P, Chemero A. Improvisation and the self-organization of multiple musical bodies. Frontiers in Psychology: Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology. 2015 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton A. Music Improvisation: Spatiotemporal Patterns of Coordination. Master’s Thesis. 2016 Available from OhioLink Electronic Theses and Dissertation Center. ( http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=ucin1457619683)

- Webber CL, Jr, Zbilut JP. Recurrence quantification analysis of nonlinear dynamical systems. In: Riley MA, Van Orden GC, editors. Contemporary nonlinear methods for behavioral scientists: A webbook tutorial. 2005. pp. 26–94. [Google Scholar]

- Zbilut JP, Webber CL. Embeddings and delays as derived from quantification of recurrence plots. Physics letters A. 1992;171(3–4):199–203. [Google Scholar]

- Webber CL, Zbilut JP. Dynamical assessment of physiological systems and states using recurrence plot strategies. Journal of applied physiology. 1994;76(2):965–973. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.2.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]