Summary

The ability of an environmental exposure (i.e. endocrine disruptor) during sex determination to reprogramme the male germline and promote an epigenetic transgenerational disease phenotype suggests that environmental factors and compounds may permanently alter the germline epigenome. This epigenetic transgenerational phenomenon will be discussed with respect to adult-onset germline disease (e.g. testicular cancer). A thorough literature review is not provided, rather a perspective is provided on how this epigenetic transgenerational toxicology should be considered in germ cell disease and testicular cancer.

Keywords: Epigenetics, Transgenerational, Endocrine Disruptors, DNA Methylation, Sex Determination

Review

Epigenetics refers to factors around the genome that do not directly involve DNA sequence to regulate the genome. Epigenetic regulation of the genome involves factors such as chromatin structure, histone modifications and DNA methylation. The DNA sequence of the genome is the essential building block of the individual and species. Therefore, the stability of the genome sequence is critical and is not readily mutated, modified or altered. The majority of environmental factors and toxicants have not been shown to directly modify DNA sequence, but promote more complex molecular origins of disease (Cunniff, 2001; Zlotogora, 2003). Many environmental factors from nutrition to environmental toxicants can alter epigenetic factors such as DNA methylation or chromatin structure (Issa, 2002; Gluckman & Hanson, 2004). A consideration of this environment–genome interaction requires epigenetic regulation to be considered as a component of the molecular basis of these environmental interactions with the genome.

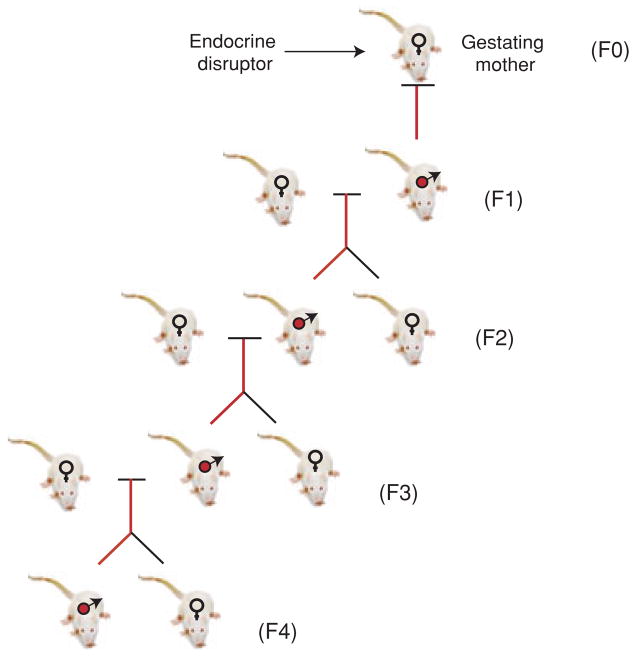

A transgenerational phenomenon is defined as the ability of an acquired physiological phenotype or disease to be transmitted to subsequent generations through the germline. A refinement of this definition is that the subsequent generation is not directly exposed to the environmental factor or toxicant. For example, the exposure of a gestating mother exposes the F0 generation mother, the F1 generation embryo and the germline of the F2 generation (Fig. 1). As multiple generations are exposed, the phenotypes in the F0, F1 and F2 generations could be due to the toxicology of the direct exposure and not necessarily transmitted through an alternate mechanism. Therefore, in the example above, the F3 generation would be the first unequivocal transgenerational generation. This does not rule out that the F2 generation does not involve a transgenerational phenotype, but simply points out a limitation to this conclusion due to the direct exposure. A multigenerational exposure can transmit a phenotype due to the toxicology of the direct exposure; however, a transgenerational phenotype requires the transmission of a phenotype independent of direct exposure.

Figure 1.

Epigenetic transgenerational adult onset disease transmitted through the male germline.

Environmental exposures have been reported to promote several transgenerational disease states (Anway & Skinner, 2006). Generally, an embryonic or early postnatal exposure is required for these transgenerational phenotypes to develop. An example includes the ability of an embryonic diethylstibesterol exposure to promote F2 generation female and male reproductive tract defects (Newbold et al., 1998). Another example is the ability of embryonic nutritional defects (i.e. caloric restriction) to promote an F2 generation diabetes phenotype (Zambrano et al., 2005). The reproducibility and frequency of these disease phenotypes suggests that they are likely epigenetic and not the outcome of DNA sequence mutations. The potential that these exposure phenotypes are epigenetic transgenerational phenotypes remains to be directly demonstrated, but suggests such a phenomenon may exist.

Recently the observation was made that the transient exposure of an F0 generation gestating rat at the time of embryonic sex determination to an endocrine disruptor can promote an adult-onset disease of spermatogenic defects and male subfertility in 90% of all male progeny across four generations (F1–F4) (Anway et al., 2005) (Fig. 1). This transgenerational phenotype was only transmitted through the male germline (sperm) and was not passed through the female germline (oocyte). Currently it is unknown why the phenotype is only transmitted through the male germline, but may involve a protection of the oocyte due to its arrest in meiosis or unique mechanisms found only in male testis development. Prior to 120 days of age the primary disease phenotype was a male testis and spermatogenic cell defect (Anway et al., 2005, 2006b). When the animals were allowed to age up to 1 year the transgenerational disease phenotype included the development of numerous disease states involving a 20% frequency of tumour development, 50% frequency of prostate disease, 40% frequency in kidney disease, 30% immune abnormalities and 30% severe infertility in the males of F1–F4 generations (Anway et al., 2006a). Females also developed transgenerational disease, but did not transmit it to subsequent generations. The clinical pathology and disease phentotypes have been thoroughly described (Anway et al., 2006a), but no testicular cancer was observed. This transgenerational (F1–F4) phenotype was induced by exposure to the endocrine disruptor vinclozolin, which is an anti-androgenic compound used as a fungicide in the fruit industry (e.g. wineries) (Kelce et al., 1994). The phenotype was also promoted by the pesticide methoxychlor which is a mixture of oestrogenic anti-oestrogenic and anti-androgenic metabolites (Anway et al., 2005). The ability of endocrine disruptors to promote adult-onset disease has been previously reviewed (Gluckman & Hanson, 2004). This is a large class of environmental toxicants ranging from plastics to pesticides (Heindel, 2005). The impact of exposure to individual compound vs. a mixture of compounds on this or most phenotypes is unknown and remains to be elucidated. These environmental toxicants generally do not promote DNA sequence mutations. The frequency of the transgenerational phenotype described above (30–90%) also could not be attributed to DNA sequence mutations that occur at a frequency generally less than 0.01% (Barber et al., 2002). The hypothesis was developed that the transgenerational phenotype described above was an epigenetic transgenerational phenotype (Anway et al., 2005; Anway & Skinner, 2006).

The potential epigenetic mechanism involved in this transgenerational phenotype was investigated through the analysis of control and vinclozolin F3 generation sperm DNA (Chang et al., 2006). A methylation-sensitive restriction enzyme analysis identified 25 DNA sequences/genes in the vinclozolin generation sperm that had an altered DNA methylation pattern and most were confirmed with bisulphite sequencing and shown to be transgenerational (Chang et al., 2006). Therefore, the endocrine disruptor exposure during sex determination reprogrammed the epigenetic programming of the developing male germline and induced the presence of new imprinted-like genes/DNA sequences that are transmitted through the male germline (i.e. paternal allele) transgenerationally. This was associated with an alteration in the transcriptomes of different organs and induction of disease phenotypes (Anway et al., 2005, 2006a). Previous studies have shown that the germ cells during sex determination undergo a de-methylation and re-methylation (Yamazaki et al., 2003) such that a reprogramming of DNA methylation of the germline by endocrine disruptors is possible. Therefore, the epigenetic transgenerational phenotype appears to involve an endocrine disruptor (i.e. vinclozolin) exposure during embryonic sex determination to epigenetically reprogramme (i.e. DNA methylation) the male germline and induce new imprinted-like DNA sequences that are transmitted through the male germline to all subsequent progeny (F1–F4) (Fig. 1) to then cause a dysregulation of the genome to alter transcriptomes in a variety of organs and appear to promote transgenerational disease (Anway et al., 2005, 2006a; Chang et al., 2006).

This epigenetic transgenerational toxicology provides a mechanism for environmental toxicants to promote transgenerational phenotypes and adult-onset disease. A large number of studies have demonstrated that embryonic or postnatal exposures can induce adult-onset disease (Gluckman & Hanson, 2004; Heindel, 2005). The mechanism for this fetal basis of adult-onset disease is largely unknown, but probably, in part, involves alterations in the epigenome. Many adult-onset disease phenotypes are not transgenerational, but manifest in the individual exposed. These individual disease exposures and phenotypes may also involve epigenetic mechanisms. A recent study demonstrated a pubertal exposure to bisphenol A promoted an alteration in DNA methylation of a number of genes and in the adult associated with a high frequency of prostate disease (Ho et al., 2006). Therefore, either an embryonic, postnatal or adult exposure could cause an epigenetic event that alters the physiology of a tissue and promotes disease. It is likely that rapidly developing organs that have the ability to alter a critical developmental step will be more sensitive to environmental exposures and epigenetic modifications. This epigenetic mechanism may be important for individual exposures and disease phenotypes. Therefore, a critical mechanism in the ability of an environmental exposure to induce an abnormal phenotype or physiology will likely be an epigenetic mechanism. Understanding toxicology on a molecular level is essential for the identification of biomarkers and the development of therapies to treat exposures. Epigenetics will be an important process to consider in the investigation of environmental exposures, environment–genome interactions and the toxicology of specific compounds.

The epigenetic transgenerational phenotype previously observed involves the epigenetic reprogramming of the male germline that promotes a spermatogenic cell defect in the adult (Anway et al., 2005, 2006b; Chang et al., 2006). This germ cell defect was detected by an increased spermatogenic cell apoptosis in stage 11 tubules, reduced sperm number and decreased motility (Anway et al., 2005, 2006b). The spermatogenic cell defect increased in frequency as the animals aged and was detected in F1–F4 generations (Anway et al., 2006a). Therefore, an environmental compound (i.e. endocrine disruptor) appears to induce a permanent male germline epigenetic change through the induction of new imprinted-like genes (Chang et al., 2006). The ability of environmental factors to epigenetically reprogramme the germline suggests fetal exposures can promote adult-onset defects and abnormalities in the germline. The possibility that the epigenetic changes in the germline may eventually promote germ cell tumours and testicular cancer now needs to be considered. The rat model used did not develop testicular cancer. Observations demonstrate that environmental exposures during embryonic sex determination can epigenetically reprogramme the male germline to then promote adult-onset spermatogenic cell defects transgenerationally. How this change in the germline epigenome may influence germ cell disease and testis cancer remains to be investigated.

The current hypothesis for germ cell tumours and testis cancer involves the development early in life of carcinoma in situ and subsequently testicular cancer (Rajpert-De Meyts, 2006). Observations suggest abnormal germ cell development and differentiation will eventually lead to germ cell tumour development. The epigenetic transgenerational phenotype described suggests environmental factors may promote an abnormal germline epigenome that can cause germline disease. The possibility that epigenetic abnormalities may be involved in germline tumours and testicular cancer now needs to be investigated. The current focus has been on germ cell chromosomal and DNA sequence abnormalities (Almstrup et al., 2005), but epigenetic changes are also likely involved. Elucidation of the epigenetic mechanisms potentially involved in germ cell disease and tumours will provide insights into how environmental factors may influence the disease, develop a better understanding into the causal mechanism of the disease and develop novel molecular markers for testicular cancer.

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge the assistance of Ms Jill Griffin and Ms Rochelle Pedersen in preparation of the manuscript. This research was supported in part by grants from the USA National Institutes of Health, NIH/NIEHS.

References

- Almstrup K, Ottesen AM, Sonne SB, Hoei-Hansen CE, Leffers H, Rajpert-De Meyts E, Skakkebaek NE. Genomic and gene expression signature of the pre-invasive testicular carcinoma in situ. Cell and Tissue Research. 2005;322:159–165. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-1084-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anway MD, Skinner MK. Epigenetic transgenerational actions of endocrine disruptors. Endocrinology. 2006;147(6 Suppl):S43–S49. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anway MD, Cupp AS, Uzumcu M, Skinner MK. Epigenetic transgenerational actions of endocrine disruptors and male fertility. Science. 2005;308:1466–1469. doi: 10.1126/science.1108190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anway MD, Leathers C, Skinner MK. Endocrine disruptor vinclozolin induced epigenetic transgenerational adult-onset disease. Endocrinology. 2006a;147:5515–5523. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anway MD, Memon MA, Uzumcu M, Skinner MK. Transgenerational effect of the endocrine disruptor vinclozolin on male spermatogenesis. Journal of Andrology. 2006b;27:868–879. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.106.000349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber R, Plumb MA, Roux I, Dubrova YE. Elevated mutation rates in the germ line of first- and second- generation offspring of irradiated male mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:6877–6882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102015399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HS, Anway MD, Rekow SS, Skinner MK. Transgenerational epigenetic imprinting of the male germline by endocrine disruptor exposure during gonadal sex determination. Endocrinology. 2006;147:5524–5541. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunniff C. Molecular mechanisms in neurologic disorders. Seminars in Pediatric Neurology. 2001;8:128–134. doi: 10.1053/spen.2001/26446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gluckman PD, Hanson MA. Developmental origins of disease paradigm: a mechanistic and evolutionary perspective. Pediatric Research. 2004;56:311–317. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000135998.08025.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heindel JJ. The fetal basis of adult disease: role of environmental exposures–introduction. Birth Defects Research. Part A, Clinical and Molecular Teratology. 2005;73:131–132. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho SM, Tang WY, Belmonte de Frausto J, Prins GS. Developmental exposure to estradiol and bisphenol A increases susceptibility to prostate carcinogenesis and epigenetically regulates phosphodiesterase type 4 variant 4. Cancer Research. 2006;66:5624–5632. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issa JP. Epigenetic variation and human disease. Journal of Nutrition. 2002;132(8 Suppl):2388S–2392S. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.8.2388S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelce WR, Monosson E, Gamcsik MP, Laws SC, Gray LE., Jr Environmental hormone disruptors: evidence that vinclozolin developmental toxicity is mediated by antiandrogenic metabolites. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 1994;126:276–285. doi: 10.1006/taap.1994.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbold RR, Hanson RB, Jefferson WN, Bullock BC, Haseman J, McLachlan JA. Increased tumors but uncompromised fertility in the female descendants of mice exposed developmentally to diethylstilbestrol. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:1655–1663. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.9.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajpert-De Meyts E. Developmental model for the pathogenesis of testicular carcinoma in situ: genetic and environmental aspects. Human Reproduction Update. 2006;12:303–323. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmk006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki Y, Mann MR, Lee SS, Marh J, McCarrey JR, Yanagimachi R, Bartolomei MS. Reprogramming of primordial germ cells begins before migration into the genital ridge making these cells inadequate donors for reproductive cloning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:12207–12212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2035119100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambrano E, Martinez-Samayoa PM, Bautista CJ, Deas M, Guillen L, Rodriguez-Gonzalez GL, Guzman C, Larrea F, Nathanielsz PW. Sex differences in transgenerational alterations of growth and metabolism in progeny (F2) of female offspring (F1) of rats fed a low protein diet during pregnancy and lactation. Journal of Physiology. 2005;566(Pt 1):225–236. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.086462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotogora J. Penetrance and expressivity in the molecular age. Genetics in Medicine. 2003;5:347–352. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000086478.87623.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]