Abstract

Coproheme decarboxylases (ChdC) catalyze the hydrogen peroxide-mediated conversion of coproheme to heme b. This work compares the structure and function of wild-type (WT) coproheme decarboxylase from Listeria monocytogenes and its M149A, Q187A, and M149A/Q187A mutants. The UV–vis, resonance Raman, and electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopies clearly show that the ferric form of the WT protein is a pentacoordinate quantum mechanically mixed-spin state, which is very unusual in biological systems. Exchange of the Met149 residue to Ala dramatically alters the heme coordination, which becomes a 6-coordinate low spin species with the amide nitrogen atom of the Q187 residue bound to the heme iron. The interaction between M149 and propionyl 2 is found to play an important role in keeping the Q187 residue correctly positioned for closure of the distal cavity. This is confirmed by the observation that in the M149A variant two CO conformers are present corresponding to open (A0) and closed (A1) conformations. The CO of the latter species, the only conformer observed in the WT protein, is H-bonded to Q187. In the absence of the Q187 residue or in the adducts of all the heme b forms of ChdC investigated herein (containing vinyls in positions 2 and 4), only the A0 conformer has been found. Moreover, M149 is shown to be involved in the formation of a covalent bond with a vinyl substituent of heme b at excess of hydrogen peroxide.

Coproheme decarboxylase (ChdC, formerly HemQ) is a key element in the coproporphyrin-dependent heme biosynthetic pathway of mainly monoderm, but also some diderm, archaea, and intermediate bacteria.1−5 In fact, it catalyzes the decarboxylation of the two propionate groups at positions 2 and 4 of iron-coproporphyrin III (coproheme) to form heme b. Many recent publications have elucidated the physiological role of ChdC,3,6,7 but its structure–function relationship is still not completely understood.

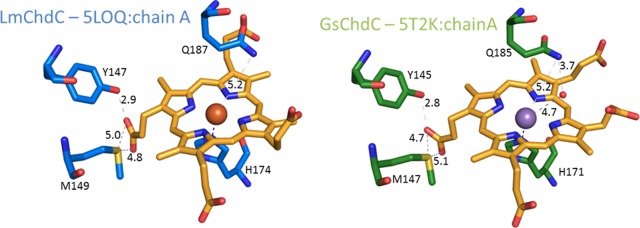

The interaction of apo-ChdC with coproheme has been recently investigated by means of spectroscopic techniques for both Listeria monocytogenes (Lm)8−10 and Staphylococcus aureus (Sa).11−13 Moreover, the crystal structures of the homopentameric coproheme-ChdC from Listeria monocytogenes (coproheme-LmChdC) at 1.69 Å resolution (5LOQ)9 and of Geobacillus stearothermophilus (Gs) ChdC with manganese-coproporphyrin III at 1.8 Å resolution (5T2K)12 have been published. Both structures show that the coproheme iron of ChdC is weakly bound by a proximal histidine (H174 in Lm). On the distal side, no water molecules are coordinated to the iron atom, suggesting the presence of a 5-coordinated iron9 in agreement with the resonance Raman (RR) spectra.9,11 The distal Gln residue (Q187 in Lm), conserved in Firmicutes ChdC, has been shown to be particularly important in the stabilization of the distal side since it interacts with incoming exogenous ligands, such as CO.12 This residue is involved in a H-bond network with an Arg residue (R133 in Lm, R131 in Sa), propionate 6, and a water molecule.12 Furthermore, it controls together with a second Arg side chain (R179 in Lm) the substrate access channel of the active site.9 The two available structures of ChdC coproporphyrin III complexes show differences in the orientation of the cofactor. In the GsChdC manganese-coproporphyrin III complex unreactive propionates p6 and p7 are solvent exposed,12 whereas in the LmChdC iron-coproporphyrin III complex reactive p2 and unreactive p7 are facing the solvent.9 Clearly, this issue is critically important for the discussion of this reaction. After thorough examination of the electron densities in the respective structures (5LOQ and 5T2K) and unpublished additional experiments on LmChdC, we have re-evaluated our analysis and now believe that the more appropriate interpretation of the structural data is that presented in the structure of GsChdC (5T2K).12

In the present paper, we compare the structure and function of wild-type (WT) coproheme-LmChdC (hereafter indicated as coproheme-WT) and its M149A, Q187A, and M149A/Q187A mutants. It should be noted that M149 interacts with p2 (5T2K) and not, as previously erroneously reported, with p4 (5LOQ).9 All the data are compared with those obtained for a reference protein, horse heart (HH) Mb (HHMb, hereafter Mb), reconstituted with coproheme.

The UV–vis, RR, and EPR data presented herein clearly show that the ferric form of the WT protein is a pentacoordinate quantum mechanically mixed-spin (5cQS). The QS state reflects a quantum mechanical admixture of intermediate (S = 3/2) and high (S = 5/2) spin states and is very unusual in biological systems. It has been found to be a distinctive characteristic of ferric cytochromes c′,14 model complexes, and Family 3 of the peroxidase-catalase superfamily.15−17 However, the structural origin and functional significance of the QS states remains elusive. Interestingly, exchange of the Met149 by Ala dramatically alters the heme coordination, since only a minor species analogous to the 5cQS observed for the WT remains, while the main species corresponds to a 6-coordinate (6c) LS species with the N atom of the Q187 residue being bound to the heme iron. Intriguingly, the activity of the mutant remains similar to that of the WT.

Moreover, in this work, we identify M149 as the amino acid that cross-links with the product heme b. In fact, we have previously reported that upon reaction with H2O2, coproheme is converted by ChdC to heme b via a three-propionate intermediate (monovinyl, monopropionate deuteroheme) and, finally, at excess hydrogen peroxide becomes cross-linked to the protein moiety.9

Experimental Procedures

Generation of LmChdC Variants

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed to obtain the LmChdC M149A, Q187A, and M149A/Q187A variants using the QuikChange Lightning Kit (Agilent Technologies). The plasmid (pETM11) encoding the N-terminal TEV-cleavable 6×His tagged fusion protein of LmChdC wild-type (ORF annotated as lmo2113 in the EGD-e genome, accession no. NC003210) was used as template for the single mutants, the template for the double mutant was the plasmid encoding LmChdC M149A. To exchange the methionine (atg) at position 149 to alanine (gcg, underlined) the following primers were used: 5′-gcctaaaaagcatatttgtttctacccagcgagtaaaaaaagggatggc-3′ and 5′-gccatccctttttttactcgctgggtagaaacaaatatgctttttaggc-3′. To exchange the glutamine (caa) at position 187 to alanine (gcg, underlined) the following primers were used: 5′-gaagctatgctggcaaagtacaagcgatcattggtggctccattg-3′ and 5′-caatggagccaccaatgatcgctt gtactttgccagcatagcttc-3′. Total volume of mutagenesis PCR was 20 μL. The PCR products were digested with dpnI and transformed into E. coli XL Gold cells. Cells were cultivated overnight at 37 °C and plasmid DNA, carrying LmChdC M149A, Q187A, and M149A/Q187A variants, was extracted using the Monarch Plasmid Mini Prep Kit (New England BioLabs Inc.) and sent for sequencing.

Expression and Purification of LmChdC Wild-Type and Variants

WT and variants were subcloned into a modified version of the pET21(+) expression vector with an N-terminal StrepII-tag, cleavable TEV protease, or into a pETM11 expression vector with an N-terminal, TEV cleavable 6×His-tag, expressed in E. coli Tuner (DE3) cells (Merck/Novagen) and purified via a StrepTrap HP or a HisTrap HP 5 mL column (GE Healthcare). The respective tag was cleaved off and the pure protein was obtained after a preparative size exclusion chromatography step (HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 pg; GE Healthcare), as described in detail previously.8 The comparison of coproheme-WT and M149A obtained with and without His-Tag (Figure S1) shows that while WT is not affected by the purification technique, the mutant is more sensitive. In particular, qualitatively the protein gives rise to the same mixture of coordination and spin states (see below), but the amount of 6cLS increases in the protein purified using the His-Tag. However, the heme b proteins, obtained upon addition of H2O2 to the coproheme complexes, are the same using a protein purified with or without His-Tag (data not shown).

Sample Preparation

Apo-Mb (horse heart, Sigma) was prepared using a modified extraction method by Teale, as described previously.8,18,19 Ferric coproheme was purchased from Frontier Scientific, Inc. (Logan, Utah, USA) as lyophilized powder. A coproheme solution at pH 7.0 in 50 mM Hepes buffer was prepared by dissolving the coproheme powder in a 0.5 M NaOH solution. A small concentrated aliquot of this solution was then mixed with an appropriate volume of 50 mM Hepes buffer, pH 7.0.

All the protein–coproheme complexes were prepared by adding the coproheme solution at pH 7.0 to the apo-proteins dissolved in 50 mM Hepes buffer, pH 7.0. The ferric heme b-LmChdC complexes of WT and variants were prepared by adding small aliquots of a concentrated solution of H2O2 in 50 mM Hepes buffer, pH 7.0, to the corresponding coproheme-LmChdC complex. The imidazole complexes of coproheme-WT and coproheme-Mb were prepared by adding small aliquots of a 0.1 M imidazole solution in 50 mM Hepes buffer at pH 7.0 to coproheme-WT and coproheme-Mb solutions until no further UV–vis spectral changes were observed.

The Fe(II)-CO adducts at pH 7.0 were prepared by flushing the ferric coproheme/heme b complexes with 12CO or 13CO (Rivoira, Milan, Italy), and then reducing the coproheme/heme b by addition of a freshly prepared sodium dithionite solution (20 mg mL–1).

Sample concentrations, in the range of 15–100 μM for UV–vis and RR measurements, were determined using an extinction coefficient (ε) of 128 800 M–1 cm–1 at 390 nm (coproheme);9 68 000 M–1 cm–1 at 395 nm (coproheme-WT and variants);10 85 800 M–1 cm–1 at 391 nm (coproheme-Mb); 76 600 M–1 cm–1 at 410 nm (heme b-LmChdC WT and variants).10

Electronic Absorption

Electronic absorption spectra were recorded using a 5 mm NMR tube (300 nm min–1 scan rate) or a 1 mm cuvette (600 nm min–1 scan rate) at 25 °C by means of a Cary 60 spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies) with a resolution of 1.5 nm. Absorption spectra were measured both prior to and after RR measurements to ensure that no degradation occurred under the experimental conditions used. For the differentiation process, the Savitzky–Golay method was applied using 15 data points (LabCalc, Galactic Industries, Salem, NH). No changes in the wavelength or in the bandwidth were observed when the number of points was increased or decreased.

Resonance Raman (RR)

The resonance Raman (RR) spectra were obtained at 25 °C using a 5 mm NMR tube by excitation with the 356.4 and 406.7 nm lines of a Kr+ laser (Coherent, Innova300 C, Coherent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Backscattered light from a slowly rotating NMR tube was collected and focused into a triple spectrometer (consisting of two Acton Research SpectraPro 2300i instruments and a SpectraPro 2500i instrument in the final stage with gratings of 3600 grooves/mm and 1800 grooves/mm) working in the subtractive mode, equipped with a liquid nitrogen-cooled CCD detector. A cylindrical lens was used to focus the laser beam on the coproheme-Mb-CO adducts.

For the low temperature experiments, a 50 μL drop of the sample was put in a 1.5-cm-diameter quartz crucible that was positioned in a THMS600 cryostat (Linkam Scientific Instruments, Surrey, UK) and frozen. After freezing the sample, the cryostat was positioned vertically in front of the triple spectrometer and the laser light was directed onto the quartz window. To avoid sample denaturation, the laser position was changed frequently. The sample temperature was maintained at 80 K.

A spectral resolution of 1.2 cm–1 and spectral dispersion of 0.40 cm–1/pixel were calculated theoretically on the basis of the optical properties of the spectrometer for the 3600 grating; for the 1800 grating, used to collect the RR spectrum obtained at λexc 406.7 nm of coproheme alone, the spectral resolution was 4 cm–1 and spectral dispersion 1.2 cm–1/pixel. The RR spectra were calibrated with indene and carbon tetrachloride as standards to an accuracy of 1 cm–1 for intense isolated bands. All RR measurements were repeated several times under the same conditions to ensure reproducibility. To improve the signal-to-noise ratio, a number of spectra were accumulated and summed only if no spectral differences were noted. All spectra were baseline-corrected.

Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (EPR)

EPR was performed on a Bruker EMX continuous wave (cw) spectrometer, operating at X-band (9 GHz) frequencies. The instrument was equipped with a high sensitivity resonator and an Oxford Instruments ESR900 helium cryostat. Spectra were recorded under nonsaturating conditions using 2 mW microwave power, 100 kHz modulation frequency, 1 mT modulation amplitude, and 40 ms conversion time, 40 ms time constant, and 2048 points. Samples (100 μL of 100–300 μM) of recombinant WT, M149A variant and coproheme-Mb were prepared in 50 mM Hepes buffer, pH 7.0, transferred into Wilmad quartz tubes (3 mm inner diameter), and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. In order to remove O2, the tubes were flushed with argon while the sample was kept frozen on dry ice. The measurements were performed at 10 K, after testing temperatures between 4 and 20 K to determine the optimum nonsaturating experimental conditions. The spectra were simulated with the Easyspin toolbox for Matlab20 using a weighted sum of simulations of the individual high-spin (HS) and low-spin (LS) species. The rhombicity was obtained from gxeff and gyeff and the relative intensities were calculated on the basis of the simulations, following the procedure of Aasa and Vanngard to account for the different integral intensity per unit spin of species that display different effective g values (as found in LS and HS centers).21,22

Enzymatic Activity of LmChdC Variants

Conversion to heme b of the coproheme complexes of LmChdC M149A, Q187A, and M149A/Q187A was followed spectroscopically on a Hitachi U3900 spectrophotometer using a quartz cuvette in a thermostated cuvette-holder (25 °C) under constant stirring, analogous to the procedure used to determine the activity of the wild-type protein.9 Briefly, Michaelis–Menten parameters were determined using the initial linear phase of increase in absorbance at 410 nm (ε410 = 76 600 M–1 cm–1).10 1 μM coproheme complexes of the LmChdC mutants M149A, Q187A, and M149A/Q187A in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, were used and the reactions were started by the addition of 20–200 μM H2O2 (Sigma); the concentrations were checked spectrophotometrically prior to each measurement (ε240 = 39.4 M–1 cm–1).23 The production rates of heme b (μM s–1) were plotted against H2O2 concentrations and the KM and Vmax calculated using a Hanes plot [extraction of catalytic parameters from the slope (1/Vmax) and the intercept (KM/Vmax)].

Titrations to determine the reaction stoichiometry of H2O2 to coproheme catalyzed by the LmChdC mutants M149A, Q187A, and M149A/Q187A were performed and monitored spectrophotometrically and via mass spectrometry as described previously.9 Mass spectrometry was set up to detect small molecules (coproheme, heme b, and monovinyl, monopropionate deuteroheme) as well as the entire protein, to detect eventual protein modifications.

Binding of Coproheme to the LmChdC Variants

The kinetics of coproheme binding to the apo-LmChdC M149A, Q187A, and M149A/Q187A variants was measured using a stopped-flow apparatus equipped with a diode array detector (model SX-18MV, Applied Photophysics), in the conventional mode. The optical quartz cell with a path length of 10 mm had a volume of 20 μL. The fastest mixing time was 1 ms. All measurements were performed at room temperature and in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. The concentration of coproheme in the cell was 1 μM and ChdC was present in excess (3.5 μM), to ensure pure spectral species of the coproheme bound proteins. The reactions were simulated and rates estimated using Pro-Kineticist software (Applied Photophysics).

Results

Binding of Coproheme to LmChdC

Insertion of coproheme into the protein leading to the formation of the WT complex causes an overall red-shift of the UV–vis spectrum. The binding of coproheme to WT has been followed monitoring the UV–vis spectral variations and shows a biphasic behavior, with a very rapid first phase (kon ∼ 1.5 × 108 M–1 s–1) and a slower second rearrangement phase (krearr ∼ 2 × 106 M–1 s–1).5,10 The kinetics of coproheme binding by apo-M149A is also biphasic (Figure S2) with similar apparent binding constants (kon ∼ 1.6 × 108 M–1 s–1; krearr ∼ 9 × 106 M–1 s–1). When the distal glutamine (Q187) is exchanged by an alanine, coproheme binding (kon) is slowed down (kon ∼ 9.4 × 107 M–1 s–1; krearr ∼ 2 × 106 M–1 s–1). In the LmChdC double mutant M149A/Q187A, the binding behavior is even more altered with estimated binding constants of kon ∼ 1.5 × 107 M–1 s–1 and krearr ∼ 7.0 × 105 M–1 s–1. The observed intermediate spectrum (representing the end of the first binding phase) also differs from the respective spectra observed in the WT and the other variants. The spectrum shows maxima similar to those found in free coproheme, although with lower extinction coefficients (Figure S2E).

Conversion of Coproheme to Heme b

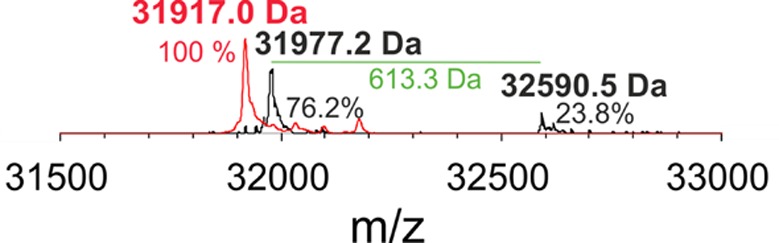

A 2-fold stoichiometric excess of H2O2 mediates the conversion of the coproheme complex into heme b. Upon addition of excess hydrogen peroxide, the prosthetic group is modified and becomes covalently bound to the protein as demonstrated by mass spectrometric analysis (Figure 1). In fact, typically, unmodified heme b does not bind to the protein and is lost during sample preparation and measurement. However, at excess H2O2 a total mass of 32 950.5 Da was detected, which corresponds to the mass of LmChdC WT plus heme b (Figure 1).9 By contrast, in LmChdC M149A the mass was 31 917.0 Da even after incubation with excess of hydrogen peroxide (Figure 1). This clearly identifies M149 as the site of covalent cross-linking. It is reasonable to assume that in the WT protein, excess H2O2 mediates the linkage between the vinyl substituent at position 2 of heme b and M149 via a sulfonium ion bond as has been demonstrated for human myeloperoxidase.24−27

Figure 1.

Cross-linking of heme b to LmChdC mediated by excess hydrogen peroxide. Mass spectrometric analysis of the entire protein of LmChdC WT (apo-form 31 977.2 Da; cross-linked 32 590.5 Da, black) and LmChdC M149A (31 917.0 Da, red). The green line with its label shows the mass difference between apo-LmChd WT and holo-LmChdC WT. The Coproheme-LmChdC complexes were titrated with H2O2 up to a 2-fold excess; subsequently, the mass spectroscopic measurements were performed on heme b-LmChdC WT and heme b-LmChdC M149A.

The decarboxylation of the propionate groups at positions 2 and 4 of coproheme leading to the formation of heme b is a relatively slow process.2,9,11 Steady-state kinetic parameters and the determination of the stoichiometry of LmChdC WT were reported in a previous study.9 In WT and the mutant M149A full conversion of coproheme to heme b requires the addition of two stoichiometric equivalents of hydrogen peroxide (Figure S3A,D). The activity of the M149A variant is characterized by an apparent kcat/KM value of 1.5 × 102 M–1 s–1 (Figure S3E), which is only slightly lower than that for the WT (1.8 × 102 M–1 s–1).9 Interestingly, the KM value for the M149A variant is approximately 4.7-fold higher and the turnover number (kcat) is also increased 4-fold compared to the WT. This indicates impaired accessibility or binding of H2O2 for the variant, which agrees well with the increased amount of the 6cLS species as demonstrated below. Conversely, the stoichiometry of coproheme conversion to heme b upon addition of hydrogen peroxide differs in the Q187A and M149A/Q187A variants. Approximately 3 equiv of hydrogen peroxide is needed to fully convert coproheme to heme b (Figure S3B-D). Steady-state kinetic parameters for the Q187A mutant show that the KM value is 5.6-fold higher than for the WT, whereas the turnover number (kcat) is almost identical.9 Due to pronounced heme bleaching and precipitation upon addition of hydrogen peroxide (Figure S3C), it was impossible to reliably determine the catalytic parameters for the double M149A/Q187A mutant.

The formation of the vinyl groups upon conversion of the coproheme complex into heme b leads to an overall red-shift of the electronic absorption spectra compared to the coproheme complexes (Figure S4, panel A) and to the appearance of two ν(C=C) vinyl stretching modes in the high frequency region of the RR spectrum at 1621 and 1632 cm–1 (Figure S4, panel B). A vinyl stretch frequency of 1632 cm–1 is quite high and indicates a fairly low degree of conjugation between the vinyl double bond and the porphyrin macrocycle.28 A lower degree of conjugation for one of the vinyl modes can explain the blue shift (by about 3–4 nm) of the Soret maximum of the heme b- LmChdC WT and mutant complexes compared to a 6cLS protein characterized by a heme group with both vinyl groups conjugated, as for the Mb-Im complex, which has a Soret maximum at 414 nm (data not shown) and both vinyl bands coincident at 1621 cm–1.29 All the spectra are typical of a main 6cLS species (pink bands), characterized by a Soret band at 410–411 nm, visible bands at 533 and 568 nm, and RR core size bands at 1503 (ν3), 1580 (ν2), and 1638 (ν10) cm–1. Interestingly, in the M149A mutant, the ν3 and ν2 bands are very broad, and the maxima are shifted toward higher frequencies with respect to those of the other proteins. This might be due to the presence of two different 6cLS forms, one corresponding to the form present in all proteins (ν3 and ν2 bands at 1503 and 1580 cm–1, respectively) whose sixth ligand has not been identified, and the other with the Q187 as the sixth ligand (ν3 and ν2 bands at 1507 and 1588 cm–1, respectively), as observed for the coproheme complex (see below).

In the spectra of the WT, Q187A, and M149A/Q187A proteins, even at very high H2O2:protein molar ratios (R > 10), a residual 5cHS species remains, as suggested by the band at 396 nm observed in the second derivative UV spectra, and the ν3 and ν2 bands at 1491 and 1574 cm–1, respectively, in the RR spectra.

Interestingly, the spectroscopic studies of the ferric heme b wild-type ChdC from M. tuberculosis(1) and S. aureus(11) indicate that the proteins are 5-coordinate (5c) high spin. Clearly, these results suggest that the heme cavity architecture of LmChdC is different.

Characterization of WT and Mutant Ferric Coproheme Containing Proteins

Figure 2 shows the UV–vis absorption spectra together with their second derivative spectra (D2) of coproheme and its complexes with Mb, LmChdC, and its M149A mutant in which the conserved Met residue, which interacts with the propionate in position 2, is replaced by the apolar Ala residue. Unlike heme b, that has two propionates and two vinyl groups, coproheme has 4 propionates and no vinyl groups. Consequently, due to the lack of vinyl conjugation, an overall blue-shift of the UV–vis spectrum with respect to heme b proteins is predicted.28 Moreover, the ν2 core-size marker band in the RR spectrum is up-shifted by up to 12 cm–1.30

Figure 2.

UV–vis absorption and second derivative (D2) spectra of coproheme and the coproheme complexes with LmChdC WT, its M149A mutant, and Mb. The band wavelengths assigned to 5cHS, 5cQS, 6cHS, and 6cLS species are indicated in orange, olive green, blue, and magenta, respectively, (see text). The spectra have been shifted along the ordinate axis to allow better visualization. The 450–700 nm region of coproheme and the coproheme complexes spectra is expanded 20- and 9-fold, respectively. The excitation wavelengths used for the RR experiments are also shown in light violet (the 356.4 nm line) and in violet (the 406.7 nm line).

Visual inspection of the electronic absorption spectra shows that the coproheme molecule and the coproheme-LmChdC complex give rise to very similar spectra. The coproheme molecule is characteristic of a pure 5cHS species, with a Soret band at 390 nm, visible bands at 492 and 530 nm, and a CT1 band at 614 nm (Figure 2). The Soret band of the coproheme-LmChdC WT complex broadens with a maximum at 393 nm (396 nm in the D2 spectrum), and in the visible region, bands at 494 and 538 nm and a CT1 band at 630 nm are observed.9,10

The case of the M149A mutant is quite different. The UV–vis spectrum of the coproheme-M149A variant is clearly a mixture of the species observed for the WT and another form, characterized by a Soret band at 406 nm, Q bands at 518 and 555 nm. A species analogous to the latter form is observed in the spectrum of the coproheme-Mb complex, which also shows two Soret bands, particularly evident in the second derivative spectrum, at 392 and 406 nm.

Figure 3 shows the corresponding RR spectra taken with two excitation wavelengths (356.4 and 406.7 nm). The UV–vis spectrum indicates that coproheme is characterized by a pure 5cHS state with core-size RR bands, observed for both excitation wavelengths, at 1493 (ν3), 1585 (ν2), and 1628 (ν10) cm–1. On the contrary, the RR spectra of the coproheme-WT complex, taken with excitation wavelengths at 356.4 and 406.7 nm, i.e., on the blue and red sides of the Soret maximum, respectively, are very similar and clearly indicate the presence of two species. A minor species with core size marker bands at 1490 (ν3), 1585 (ν2), and 1628 (ν10) cm–1, analogous to the 5cHS form observed for pure coproheme, and a main species with core size marker bands at 1503 (ν3), 1579 (ν2), and 1635 (ν10) cm–1. The assignment of this latter form is not straightforward, since although the RR might correspond to a 6cLS species, there is no evidence for such a species in the UV–vis spectrum. In fact, the Soret band at 393 nm and CT band at 630 nm are consistent with a 5cHS species.

Figure 3.

High frequency region RR spectra obtained at room temperature, with the 356.4 (Panel A) and 406.7 nm (Panel B) excitation wavelengths, of coproheme, and the coproheme complexes of LmChdC WT, its M149A mutant, and Mb. The band wavenumbers assigned to 5cHS, 5cQS, 6cHS, and 6cLS species are indicated in orange, olive green, blue, and magenta, respectively (see text). The spectra have been shifted along the ordinate axis to allow better visualization. Experimental conditions: (A) laser power at the sample 5 mW, average of 10 spectra with 120 min integration time (Coproheme); laser power at the sample 2 mW; average of 7 spectra with 70 min integration time (WT), 8 spectra with 80 min integration time (M149A), and 24 spectra with 240 min integration time (Mb). (B) laser power at the sample 5 mW; average of 2 spectra with 10 min integration time with 1800 grating (Coproheme), 9 spectra with 90 min integration time (WT), 4 spectra with 40 min integration time (M149A), and 6 spectra with 60 min integration time (Mb).

Unlike the WT, the RR spectra of the coproheme-M149A variant taken with the two excitation wavelengths are quite different. The spectrum obtained with the 356.4 nm laser line, in resonance with the Soret band at 396 nm, is almost identical to that observed for the WT, in terms of both the band frequencies and intensities. In contrast, the most intense RR bands in the spectrum obtained with the 406.7 nm laser line, in resonance with the Soret band at 406 nm, are at 1507 (ν3), 1593 (ν2), and 1640 (ν10) cm–1. This spectrum is assigned to a 6cLS heme. Interestingly, the spectrum very closely resembles that of the coproheme-Mb complex. Two Soret bands, particularly evident in the second derivative spectrum, at 392 and 406 nm are observed. The Soret at 406 nm, Q bands at 525 and 555 nm, and the RR bands at 1508 (ν3), 1594 (ν2), and 1641 (ν10) cm–1 are assigned to a 6cLS species. These RR bands are strongly intensified with 406.7 nm excitation, but markedly lose intensity in the spectrum obtained with 356.4 nm excitation, in resonance with the Soret band at 392 nm. This Soret band, together with the bands at 486 and 614 nm, is assigned to the overlapping contribution of a 5cHS and a 6cHS species that, however, can be easily distinguished in the RR spectrum. The bands at 1495 (ν3), 1584 (ν2), and 1630 (ν10) cm–1 are assigned to a 5cHS species and those at 1483 (ν3), 1575 (ν2), and 1618 (ν10) cm–1 to a 6cHS species. Therefore, as expected, with the 356.4 nm excitation, not only does the 6cLS spectrum markedly decrease in intensity, but interestingly, the ν2 band almost disappears. The loss of the ν2 band with this excitation is taken as a useful marker for the assignment of 6cLS species. In order to confirm these findings, we added imidazole to the WT in order to obtain a 6cLS heme as a model compound.

The exogenous imidazole does not bind completely the coproheme iron (Figure 4). Nevertheless, the bis-His complex is clearly observed, and is characterized by the same spectroscopic features observed for the 6cLS of the coproheme-Mb complex, its adduct with imidazole, and the coproheme-M149A mutant [Soret band at 403 and 407 nm in D2, visible bands at 525 and 555 nm; core size RR bands at 1505 (ν3), 1590 (ν2) and 1637 (ν10) cm–1], all assigned to a 6cLS species. Taken together, these observations also strongly indicate that the heme state of coproheme-WT, characterized by a Soret at 393 nm (Figure 2) and RR bands at 1503 (ν3), 1579 (ν2), and 1635 (ν10) cm–1 (Figure 3), cannot be a 6cLS form. In analogy with the heme containing peroxidases belonging to Family 3 of the peroxidase-catalase superfamily, this form is assigned to a quantum mechanically mixed-spin (QS) state.15−17 In fact, as previously reported,15,31 the 5cQS species gives rise to (i) an electronic absorption spectrum similar to that of a 5cHS heme but with a shorter wavelength transitions; (ii) a CT band at 630–635 nm; (iii) RR core size marker bands frequencies similar to that of a 6cLS species; (iv) EPR spectra with g12 values in the range 4 < g12 < 6.

Figure 4.

UV–vis absorption and second derivative spectra (D2) (Panel A) and RR spectra in the high frequency region (Panel B) of the coproheme complexes of WT and Mb with and without the addition of imidazole (ImH). The band wavelengths and wavenumbers assigned to 5cHS, 5cQS, 6cHS, and 6cLS species are indicated in orange, olive green, blue, and magenta, respectively (see text). The spectra have been shifted along the ordinate axis to allow better visualization. The 450–700 nm region of the spectra in Panel A is expanded 10-fold. Experimental conditions of the RR spectra: 406.7 nm excitation wavelength, laser power at the sample 5 mW; average of 9 spectra with 90 min integration time (WT), 10 spectra with 100 min integration time (WT + ImH), 5 spectra with 50 min integration time (Mb + ImH), and 6 spectra with 60 min integration time (Mb).

To gain further insight into the spin state and heme coordination of this species, the X-band EPR spectrum of the coproheme-WT complex was recorded (Figure S5 and Table 1). Three different species are present. The most abundant is characterized by g values at 5.90, 5.10, 2.00 (g12 = 5.50), which confirms the presence of a 5cQS species. A 5cHS (6.30, 5.45, 2.00; g12= 5.88), and a small amount of a 6cLS species (2.90, 2.27, 1.60) that is absent in the RR room temperature spectrum, are also observed. In the case of the M149A mutant, in agreement with the RR spectra, the most abundant species is a 6cLS form (2.96, 2.27, 1.60). Its g1 value (2.96) is slightly higher than that of the WT LS species, possibly suggesting a more axial interaction of the heme ligand. Moreover, two different 5cHS species are present, one of which (6.30, 5.45, 2.00; g12 = 5.88) is identical to that observed in the WT sample. In agreement with the RR spectra, the coproheme-Mb EPR spectrum is characterized by a dominant 6cLS form (2.97, 2.27, 1.60), and two 5cHS species. One of the latter, the least abundant species, displays a very small rhombicity (5.90, 5.85, 1.99; g⊥ = 5.88); hence, it can effectively be considered to be very close to a 6cHS form. Nevertheless, an alternative simulation using a pure 6cHS state produced a slightly poorer correspondence between experimental and simulated spectra.

Table 1. EPR Parameters of the Coproheme Complexes of LmChdC WT, Its M149 Mutant and Mb, Compared to Those of Soybean Peroxidase (SBP).

|

g strain |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | g1 | g2 | g3 | g12 | Assignment | Ra % | Ib % | g1 | g2 | g3 |

| WT | 6.30 | 5.45 | 2.00 | 5.88 | 5cHS | 5.3 | 19 | 0.35 | 0.20 | 0.025 |

| 5.90 | 5.10 | 2.00 | 5.50 | 5cQS | 5.0 | 70 | 0.25 | 1.00 | 0.05 | |

| 2.90 | 2.27 | 1.60c | 6cLS | 11 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.15 | |||

| M149A | 6.30 | 5.45 | 2.00 | 5.88 | 5cHS | 5.3 | 12 | 0.35 | 0.20 | 0.025 |

| 5.97 | 5.73 | 2.00 | 5.85 | 5cHS | 1.5 | 23 | 0.30 | 0.40 | 0.015 | |

| 2.96 | 2.27 | 1.60c | 6cLS | 65 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.15 | |||

| Mb | 6.20 | 5.57 | 2.00 | 5.89 | 5cHS | 4.0 | 36 | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.025 |

| 5.90 | 5.85 | 2.00 | 5.88 | 5cHS | 0.3 | 15 | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.015 | |

| 2.97 | 2.27 | 1.60c | 6cLS | 49 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.15 | |||

| SBPd | 5.89 | 4.85 | 2.00 | 5.37 | 5cQS | |||||

| 3.25 | 2.07 | 6cLS | ||||||||

The g values of the 6cLS species for all three cases are similar to those of a bis-His heme coordination where the two imidazole planes are approximately parallel.32,33 Nevertheless, although there is a His residue in the coproheme-Mb complex, there are no His residues in the distal cavity of ChdC.9 A possible alternative explanation of the g1 signal for ChdC might be an OH--Fe-His species where the OH– ligand is strongly H-bonded, as reported for HRPC and HRPA2 at alkaline pH.34,35 However, the H-bonding partner in the ChdC distal cavity is not obvious and at alkaline pH we did not observe any 6cLS hydroxo complex formation. In fact, in glycine, the buffer binds the heme iron, and with other buffers (e.g., borate) at alkaline pH we observed the release of the coproheme from the complex (data not shown). Conversely, the observation that the core-size RR bands of the coproheme-Mb-His complex are identical to those assigned to the 6cLS in coproheme-Mb (Figure 3B) is in complete agreement with the bis-His coordination determined from the EPR analysis.

Table 1 reports the EPR parameters of the coproheme complexes of LmChdC WT, its M149 mutant and Mb, compared to those of soybean peroxidase (SBP). Tables S1 and S2 report the assignment of the UV–vis maxima and the main RR core-size marker bands of the various species.

To clarify this apparently inconsistent set of data and identify the nature of the sixth ligand in the LS coproheme-LmChdC complexes, we have considered which other key residues in the distal cavity might be able to bind the Fe atom via a N atom. Since the distal Gln residue (Q187 in Lm), conserved in Firmicutes ChdC, has been shown to be particularly important in the stabilization of the distal side due to its interaction with incoming exogenous ligands, such as CO,12 we focused on this residue by studying the single Q187A and double Q187/M149A variants.

Figure 5 compares the UV–vis and second derivative (D2) spectra (Panel A) and RR spectra in the high frequency region (Panel B) of the coproheme complexes of WT, and the Q187A, M149A/Q187A, and M149A mutants. In the absence of Q187, the spectra resemble very closely that of the WT and the 6cLS species, observed in the coproheme-M149A spectra (pink bands), completely disappears. Clearly, this allows us to conclude that the 6cLS species observed in this mutant is due to the Q187 residue, through binding of its N atom to the heme iron. Mutation of the Q187 residue also gives rise to a small amount of a 6cHS species (blue bands, ν3 and ν10 at 1482 and 1614 cm–1, respectively) at the expense of the 5cQS form. This suggests that the mutation also alters the H-bonding network involving the conserved distal Arg133, propionate 6 and a water molecule.12

Figure 5.

UV–vis absorption and second derivative (D2) spectra (Panel A) and RR spectra in the high frequency region (Panel B) of the coproheme complexes with WT and the Q187A, M149A/Q187A, and M149A mutants. The band wavelengths and wavenumbers assigned to 5cHS, 5cQS, 6cHS, and 6cLS species are indicated in orange, olive green, blue, and magenta, respectively. The spectra have been shifted along the ordinate axis to allow better visualization. The 450–700 nm region of the spectra in Panel A is expanded 9-fold. Experimental conditions of the RR spectra: 406.7 nm excitation wavelength, laser power at the sample of 5 mW, average of 9 spectra with a 90 min integration time (WT), 14 spectra with a 140 min integration time (Q187A), 10 spectra with a 100 min integration time (M149A/Q187A), and 4 spectra with a 40 min integration time (M149A).

The EPR data are in very good agreement not only with the RR spectra at room temperature but also with those obtained at 80 K (Figures 6 and S6). The comparison between the 80 K RR spectra obtained for excitation at 356.4 and 406.7 nm confirms the presence of a 5cQS species (ν3 1507, ν2 1584, and ν10 1637 cm–1), a 5cHS species (ν3 1490, ν2 1570 and ν10 1627 cm–1), and a 6cLS form (ν3 1507, ν2 1594 and ν10 1640 cm–1) for the WT, and mainly a 6cLS (ν3 1510, ν2 1597, and ν10 1643 cm–1) with only a small amount of 5cHS (ν3 1490, ν2 1570, and ν10 1627 cm–1) for the M149 mutant (Figure S6). The 80 K RR spectrum of coproheme-Mb complex is also characterized mainly by a 6cLS species (ν3 1511, ν2 1599, and ν10 1646 cm–1) and a small amount of 5cHS (ν2 1588 cm–1) and 6cHS (ν2 1575 cm–1) states. The slight differences between the RR frequencies of the 6cLS species of the M149A mutant and WT is consistent with the EPR analysis and suggests that the two 6cLS species differ in terms of ligand type or strength of ligand interaction with the heme iron. Moreover, the absence of any 5cQS species in the EPR and 80 K RR spectra in the mutant suggests that a structural rearrangement may occur following mutation.

Figure 6.

Heme coordination for the coproheme complexes of LmChdC, its M149A mutant, and Mb determined by RR and EPR spectroscopy at room and low temperatures..

The previously reported analysis of ferric coproheme-LmChdC, based principally on UV–vis and EPR spectroscopies at pH 7, concluded that the protein was characterized by the existence of a predominant high-spin state and a minor low spin form.10 The apparent contrast in assignment of the dominant spin state with that of the present study can be understood by taking into account a critically important difference between the respective samples. The previous study was conducted on proteins in phosphate buffer, which is known to cause possible artifacts in the EPR spectrum at low temperature.36 Accordingly, although the previously reported EPR spectrum has some similarities with that presented here, there are also important clear differences.

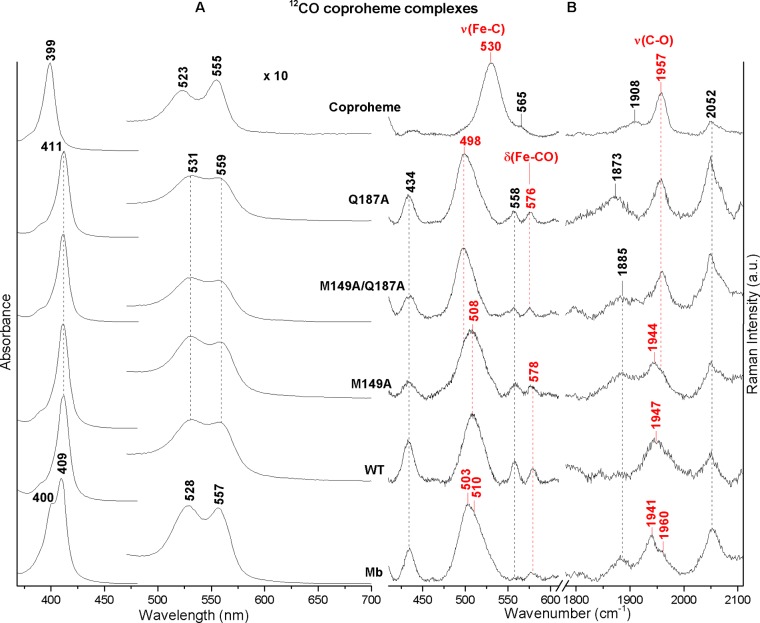

CO Complexes of the Coproheme and Heme b WT and Mutant Proteins

In order to probe the properties of the distal cavity we studied the CO complexes of both the coproheme and heme b WT and mutants. In fact, CO is a sensitive probe for investigating distal and proximal effects on ligand binding of heme proteins since back-donation from the Fe dπ to the CO π* orbitals is modulated by polar interactions with distal protein residues, which alters the electron distribution in the FeCO unit changing the order of the C–O bond, and by variations in the donor strength of the trans ligand.37 A positively charged electrostatic field or H-bond residues favors back-donation, strengthening the Fe–C bond and correspondingly weakening the C–O bond, thereby increasing the ν(FeC) vibrational frequencies and decreasing the ν(CO) frequencies. Conversely, a negatively charged electrostatic field has the opposite effect.38

As for heme protein-CO complexes, the ferrous coproheme proteins bind CO giving rise to a 6cLS species. The UV–vis spectra (Figure 7, panel A) are all blue-shifted compared to heme b CO complexes (see below) due to the lack of conjugation of the vinyl groups in the coproheme complexes. Accordingly, the UV–vis spectrum of the coproheme-CO complex is characterized by a Soret band at 399 nm, 12 nm blue-shifted compared to that of the free heme-CO complex,39 with ν(FeC) and ν(CO) stretching modes at 530 and 1957 cm–1 (Figure 7, panel B), very similar to those observed for the heme-CO complex (at 530 and 1955 cm–1).39 The electronic absorption spectra of the WT and its selected mutants (M149A, Q187A, and M149A/Q187A) are very similar, with Soret, α, and β bands at 411, 531, and 559 nm, respectively. Interestingly, the corresponding spectrum of coproheme-Mb-CO shows two bands in the Soret region at 400 and 409 nm. However, the RR spectra obtained with both the 406.7 and 413.1 nm excitation wavelengths are identical (data not shown). For both excitation wavelengths, on the basis of the isotope shift in 13CO versus 12CO (Figure S7), two CO conformers have been identified characterized by (i) ν(FeC) at 503 cm–1 and ν(CO) at 1956 cm–1, and (ii) ν(FeC) at 510 cm–1 and ν(CO) at 1941 cm–1. Moreover, a weak band at 578 cm–1 assigned to the δ(FeCO) bending mode is observed (Figure 7, panel B). Coproheme-WT shows only one conformer with ν(FeC) at 508 cm–1 and ν(CO) at 1947 cm–1, similar to the frequencies observed in the M149A variant (508 and 1944 cm–1). In this variant, however, a second conformer is observed, characterized by ν(FeC) at 498 cm–1 and ν(CO) at 1957 cm–1, which is the only form present in the Q187A and M149A/Q187A mutants.

Figure 7.

UV–vis (panel A) and RR (panel B) spectra in the low (left) and high (right) frequency regions of the 12CO adducts of the coproheme complexes of Mb, WT, M149A, M149A/Q187A, Q187A, and coproheme. The frequencies of the ν(FeC), δ(FeCO), and ν(CO) modes are indicated in red. The spectra have been shifted along the ordinate axis to allow better visualization. Panel A: the 480–700 nm region is expanded 10-fold. Panel B: experimental conditions: Mb and coproheme: λexc 406.7 nm, laser power at the sample 5 mW, average of 4 spectra with 40 min integration time and 10 spectra with 100 min integration time in the low and high frequency regions, respectively (Mb), average of 6 spectra with 60 min integration time and 12 spectra with 120 min integration time in the low and high frequency regions, respectively (coproheme); WT and its mutants, λexc 413.1 nm, laser power at the sample 1–3 mW; average of 28 spectra with 280 min integration time and 22 spectra with 220 min integration time in the low and high frequency regions, respectively (WT), average of 6 spectra with 60 min integration time and 18 spectra with 180 min integration time in the low and high frequency regions, respectively (M149A), average of 6 spectra with 60 min integration time and 15 spectra with 150 min integration time in the low and high frequency regions, respectively (M149A/Q187A), and average of 9 spectra with 90 min integration time and 15 spectra with 150 min integration time in the low and high frequency regions, respectively (Q187A).

Figure 8 shows a plot of the ν(FeC) versus ν(CO) frequencies of the coproheme complexes of LmChdC and its variants, Mb, coproheme, and the coproheme complexes of SaChdC and its variants.12 A negative linear correlation between the ν(FeC) and ν(CO) frequencies has been found for a large class of heme protein CO complexes and heme model compounds containing His as the fifth iron ligand. The line reported in Figure 8 has been obtained according to eq 1 of ref (37). The ν(FeC)/ν(CO) position along the correlation line reflects the type and strength of distal polar interactions. Above the imidazole back-bonding correlation line another parallel line is typical of heme proteins or model compounds with a trans ligand weaker than His,40 or no ligand at all.37,41 Similar to the free heme-CO complex, the free coproheme-CO complex lays on this line, in agreement with the formation of a 5cHS complex.39 The two conformers found for the Mb complex are reminiscent of those established for (heme b) sperm whale (SW) MbCO. At neutral pH two main conformers have been identified by RR and IR spectroscopy for the CO adduct of SWMb, named A1 (508/1946 cm–1) and A3 (518/1932 cm–1), with A1 being the main species. In addition, a very weak species (A0, 493/1965 cm–1) is observed at neutral pH that increases at acid pH at the expense of the A1 conformer.42,43 The position of the distal His has been identified to be responsible for the different forms, which correspond to a closed (A1) and an open form (A0).43 Unlike SWMb, for HHMb only one species has been identified by RR corresponding to form A1,44 while two ν(CO) stretching modes (at 1944 and 1932 cm–1) have been observed in the IR spectrum,45 suggesting the presence also of form A3. By analogy, we name the two conformers observed in the coproheme-Mb complex A1 (510/1941 cm–1) and A0 (503/1956 cm–1), however, this latter form is not completely open but shows only a decreased polar interaction with the distal residues.

Figure 8.

Back-bonding correlation line of the ν(Fe–C) and ν(C–O) stretching frequencies of the coproheme-CO complexes of Mb (blue solid squares), SaChdC WT, and selected mutants (green solid triangles), LmChdC WT and selected mutants (red solid circles), heme, and coproheme. The three conformers of SWMb (heme b) are also reported (black solid squares). The dotted lines indicate the approximate delineation between the frequency zones of the A0, A1, and A3 states discussed in the text. The frequencies and references of the ν(Fe–C) and ν(C–O) stretching modes of the various CO adducts are reported in Table 2.

CO binds WT giving rise to only one conformer with frequencies that are similar to those of the more polar conformer (A1), while the M149A variant shows both the A1 and A0 forms. Since the A1 species disappears upon replacement of the Q187 residue, its presence is due to the H-bonding stabilization of CO by this residue. These results are in a very good agreement with those previously reported for the SaChdC–CO complexes. In particular, the WT complex showed a moderate H-bond donation or electrostatic interaction with the bound CO and the distal Q185 residue.12

Unlike the coproheme-CO complexes, the heme b protein CO adducts show very similar 6cLS CO spectra, with an overall 3–4 nm blue-shift of the UV–vis spectra compared to HHMb (Figure S8, panel A), consistent with the frequency upshift of one vinyl mode (data not shown) observed for the ferric heme b proteins and, hence, lower vinyl conjugation with the heme. On the basis of their isotope shifts in 13CO (Figure S9), the ν(FeC) bands of the WT and mutant CO adducts have been assigned to the band around 500 cm–1 present in all the proteins. The corresponding ν(CO) stretching mode is observed at 1960 cm–1 in the WT. Unfortunately, due to the high fluorescent background the corresponding ν(CO) stretching modes for all the mutants are not clearly defined. This form, similar to that found for the heme b SaChdC–CO complexes12 and identical to the A0 form found in the coproheme-CO complexes (Figure 8), shows a low polar interaction with distal residues (Table 2).

Table 2. ν(Fe–C) and ν(C–O) Stretching Modes Frequencies (cm–1) of the Coproheme- and Heme b-CO Adducts of the Proteins and Model Compounds Reported in Figure 8.

| Conformers | ν(FeC) | ν(CO) | ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| coproheme | ||||

| HH | ||||

| Mb | A0 | 503 | 1960 | This work |

| Mb | A1 | 510 | 1941 | This work |

| Lm ChdC | ||||

| WT | A1 | 508 | 1947 | This work |

| M149A | A1 | 508 | 1944 | This work |

| M149A | A0 | 498 | 1957 | This work |

| Q187A | A0 | 498 | 1957 | This work |

| M149A/Q187A | A0 | 498 | 1957 | This work |

| SaChdC | ||||

| WT | A1 | 513 | 1941 | (12) |

| Y145S | A1 | 508 | 1949 | (12) |

| R218A | A1 | 507 | 1947 | (12) |

| Q185A | A0/A1 | 498 | 1953 | (12) |

| R131A | A1 | 506 | 1950 | (12) |

| K149A | A1 | 507 | 1941 | (12) |

| Coproheme | 530 | 1957 | This work | |

| Heme b | ||||

| SW | ||||

| Mb | A3 | 517 | 1932 | (42,43) |

| Mb | A1 | 508 | 1944 | (42,43) |

| Mb | A0 | 493 | 1965 | (42,43) |

| HH | ||||

| Mb | A3 | - | 1932 | (45) |

| Mb | A1 | 509 | 1944 | (44) |

| Lm ChdC WT | A0 | 500 | 1960 | This work |

| Sa ChdC WT | A0 | 498 | 1958 | (12) |

| Heme b | 530 | 1955 | (39) | |

Discussion

The electronic absorption spectra of coproheme-LmChdC WT are very similar to the corresponding spectra of SaChdC, the latter being characterized by Soret, visible α/β, and CT1 bands at 394, 497/533, and 630 nm, respectively. However, the RR spectra of the two proteins are different. In particular, the coproheme-SaChdC complex is characteristic of a 5cHS form and no species with high frequencies corresponding to a QS state have been observed.11

The QS spin state is very rare in heme proteins. Moreover, not only is its possible involvement in protein function unclear, but the structural determinants of 5cQS vs 5cHS spin states have also been a matter of extensive debate and remain elusive.14,15 The formation of a 5cQS heme has been mainly associated with a weak axial ligand. However, this feature does not appear to be sufficient to cause a QS state. In fact, while the lack of a H-bonding partner for the proximal imidazole ligand may account for the presence of a 5cQS state in cytochromes c′,14 heme-containing peroxidases are characterized by a conserved strong H-bond between the Nδ atom of the imidazole ligand and the carboxylate of an aspartic side chain, which acts as H-bond acceptor, imparting an imidazolate character to the histidine ligand.15,16 Interestingly, in both ferrous coproheme-LmChdC and -SaChdC, the ν(Fe-Im) stretching mode is observed at 214 cm–1,9,11 confirming that the Nε of the imidazole of the proximal His (H174) is weakly bonded to the heme iron in agreement with the crystal structure (5LOQ). However, as mentioned above, coproheme-SaChdC does not display a QS state.11

As an initial step in the decarboxylase reaction mechanism, coproheme decarboxylases must bind the substrate coproheme prior to reaction with hydrogen peroxide. The coproheme binding constants for LmChdC and SaChdC have been reported previously10 and have demonstrated that the large substrate finds its way into the binding pocket very rapidly. Coproheme binding to the M149A variant is WT-like (Figure S2), but the final spectrum differs from that of WT in terms of its spin states (Figure 2). Binding of coproheme (kon) to the Q187A variant and the double mutant M149A/Q187A is significantly lower than for WT, whereas the second phase, referred to as the rearrangement phase, is similar to the WT protein in these variants. The M149A variant is an exception since the rearrangement phase is faster (Figure S2). The residue Q187, which acts as internal ligand causing the 6cLS in the M149A variant, is part of the active site and is located on the distal heme side. In the available crystal structures, its amino acid side chain has been found to point away from the heme and is more than 5 Å distant from the heme iron (Figure 9). Therefore, the distal cavity appears to be very flexible, and its flexibility appears to be confirmed by the finding that in the M149A variant two CO conformers have been found which resemble the open (A0) and closed (A1) conformations observed in SWMb-CO.43 We suggest that the Q187 residue has a similar role to that of the distal His in native SWMb: in the absence of the Q187 residue only the A0 conformer is observed in the single Q187A and M149A/Q187A double variants. The interaction between M149 and propionyl 2 has an important role in keeping the Q187 residue correctly positioned to close the distal cavity. This is confirmed by the CO adducts of the two heme b-ChdCs considered herein, both of which show only the A0 conformer.

Figure 9.

Active site architecture of LmChdC and GsChdC. LmChdC is depicted in blue and GsChdC in green. Distances are shown as gray dashes and labeled in black.

Interestingly, Q187 is not essential for the reactivity of coproheme with hydrogen peroxide to yield the three-propionate intermediate and, subsequently, heme b; however, its role is clearly non-negligible. Therefore, it is suggested to be important for the active site architecture. Moreover, the Q187A and M149A/Q187A variants are much more prone to heme bleaching during the catalytic reaction than the WT and M149A single variant (Figure S3). The stoichiometric excess of hydrogen peroxide needed to fully convert coproheme to heme b is WT-like for the M149A mutants, whereas when Q187 is mutated the reaction is less efficient and a higher excess of hydrogen peroxide is needed (Figure S3D). Since the turnover number (kcat) for the Q187A mutant is WT-like, but the KM-value is 5.6-fold higher and heme bleaching is more pronounced in this variant, Q187 most probably has a significant role in binding and stabilization of the incoming hydrogen peroxide (Figure S3E). A similar role for this residue was already proposed in SaChdC.12 Q187 is conserved in Firmicutes (clade 1); in active ChdCs from Actinobacteria (clade 2) an alanine can be found at the corresponding position.5 Interestingly, actinobacterial ChdCs are not prone to heme bleaching and convert coproheme more efficiently to heme b than ChdCs from Firmicutes.5 In these clade 2 ChdCs another player has to take over the role of Q187 in LmChdC. The 4.7-fold higher KM-value of the M149A variant (Figure S3E) compared to the WT can be explained by the presence of the 6cLS species resulting from the binding of the Q187 residue, which has to be displaced by the incoming hydrogen peroxide. Therefore, M149 is also suggested to be important for the active site architecture, as upon its exchange with alanine, Q187 moves closer to the heme iron and can act as a low-spin ligand.

Furthermore, we propose that M149 is involved in the formation of a covalent bond with one vinyl substituent of modified heme b mediated by excess hydrogen peroxide (Figure 1). Most probably a sulfonium ion linkage is established, as has been demonstrated for human myeloperoxidase24 and the S160M variant of ascorbate peroxidase.46 This (autocatalytic) radical mechanism typically starts by the formation of Compound I upon reaction of the ferric heme b enzyme with hydrogen peroxide. In these peroxidases Compound I initiates this reaction by oxidizing the adjacent Met side chain. In coproheme decarboxylases, Compound I is hypothesized to be the redox intermediate that leads to initiation of coproheme decarboxylation.9,12,46 It cannot be excluded that the observed cross-linking might be an in vitro artifact that occurs due to the use of H2O2 concentrations higher than those found under physiological conditions. Nevertheless, it is also possible that it is physiologically relevant as a potential rescue mechanism to avoid undesirable oxidative side reactions. In the latter scenario, heme b would be covalently sequestered in the case where too much H2O2 is present and, subsequently, the protein together with the linked heme would be degraded. The equilibrium of heme biosynthesis and degradation is crucial to any organism and utilizes many different strategies.47

Conclusions

In this work we have presented a thorough investigation of the active site architecture of coproheme decarboxylase WT and selected variants from Listeria monocytogenes using various spectroscopic techniques and also probed the impact of conserved active site amino acids on its catalytic activity. The M149 and Q187 residues are conserved throughout the clade 1 coproheme decarboxylases, which are constituted by representatives from Firmicutes, Thermi, and Euryarcheota.5,17 In contrast to coproheme-SaChdC WT, ferric coproheme-LmChdC WT is predominantly characterized by the uncommon 5cQS state, even though the same conserved residues constitute the active site architecture. Further differences between LmChdC and SaChdC concern the degree of heme bleaching during the reaction of the coproheme-bound ChdC with hydrogen peroxide. SaChdC requires a higher stoichiometric excess (5-fold)12 for complete turnover (coproheme to heme b) than LmChdC (2-fold).9 Heme bleaching in the WT enzymes is more pronounced in SaChdC, as no isosbestic point can be observed in the UV–vis spectra of hydrogen peroxide titrations of the coproheme-bound enzyme,11 in contrast to LmChdC.9 Interestingly, in a similar manner, superimposable active site architectures of chlorite dismutases from different phylogenetic clades display surprisingly pronounced differences concerning catalytic parameters, ligand binding constants, or inactivation mechanisms.48−51 M149 and Q187 have been shown to be structurally important for the active site architecture of the coproheme-bound enzyme, as highlighted by the observed catalytic and spectroscopic differences of the mutants. The features of the respective active site architectures of other ChdCs will be the targets of further investigation to gain a more comprehensive insight into the function and mechanism of ChdCs. Notably, a phenylalanine can be found at the M149 position in clade 2 and 4 ChdCs5 and an alanine (clade 2) or leucine (clade 4) at the Q187 position.

Acknowledgments

We thank Daniel Maresch for technical support performing mass spectrometry analysis. This project was supported by the Austrian Science Fund, FWF [stand-alone project P29099].

Glossary

Abbreviations

- coproheme

iron coproporphyrin III

- ChdC

coproheme decarboxylase

- LmChdC

ChdC from Listeria monocytogenes

- WT

wild-type of ferric coproheme-LmChdC

- Mb

ferric myoglobin

- HH

horse heart

- SW

sperm whale

- coproheme-Mb

coproheme bound myoglobin complex

- M149A

LmChdC Met149Ala variant

- Q187A

LmChdC Gln187Ala variant

- M149A/Q187A

LmChdC Met149Ala/Gln187Ala double variant

- SBP

soybean peroxidase

- CT1

charge-transfer band due to a2u(π) → eg(dπ) transition

- 5c

five-coordinated

- 6c

six-coordinated

- HS

high spin

- LS

low spin

- RR

resonance Raman

- EPR

electron paramagnetic resonance

- QS

quantum mechanically mixed spin

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00186.

UV–vis absorption, second derivative, and high frequency region RR spectra; Coproheme binding to the LmChdC variants; Enzymatic activity of the LmChdC M149A, Q187A, and M149A/Q187A variants; EPR spectra; UV–vis and RR core size band assignments of coproheme and coproheme complexes; UV–vis and RR spectra in the low and high frequency regions (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Dailey T. A.; Boynton T. O.; Albetel A. N.; Gerdes S.; Johnson M. K.; Dailey H. A. (2010) Discovery and Characterization of HemQ: an essential heme biosynthetic pathway component. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 25978–25986. 10.1074/jbc.M110.142604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailey H. A.; Gerdes S.; Dailey T. A.; Burch J. S.; Phillips J. D. (2015) Noncanonical coproporphyrin-dependent bacterial heme biosynthesis pathway that does not use protoporphyrin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112, 2210–2215. 10.1073/pnas.1416285112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailey H. A.; Dailey T. A.; Gerdes S.; Jahn D.; Jahn M.; O’Brian M. R.; Warren M. J. (2017) Prokaryotic Heme Biosynthesis: Multiple Pathways to a Common Essential Product. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 81 (1), e00048–16. 10.1128/MMBR.00048-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosugi N.; Araki T.; Fujita J.; Tanaka S.; Fujiwara T. (2017) Growth phenotype analysis of heme synthetic enzymes in a halophilic archaeon, Haloferax volcanii. PLoS One 12, e0189913. 10.1371/journal.pone.0189913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfanzagl V.; Holcik L.; Maresch D.; Gorgone G.; Michlits H.; Furtmüller P. G.; Hofbauer S. (2018) Coproheme decarboxylases - Phylogenetic prediction versus biochemical experiments. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 640, 27–36. 10.1016/j.abb.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs C.; Dailey H. A.; Shepherd M. (2016) The HemQ coprohaem decarboxylase generates reactive oxygen species: implications for the evolution of classical haem biosynthesis,. Biochem. J. 473, 3997–4009. 10.1042/BCJ20160696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayfield J. A.; Hammer N. D.; Kurker R. C.; Chen T. K.; Ojha S.; Skaar E. P.; DuBois J. L. (2013) The chlorite dismutase (HemQ) from Staphylococcus aureus has a redox-sensitive heme and is associated with the small colony variant phenotype,. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 23488–23504. 10.1074/jbc.M112.442335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofbauer S.; Hagmüller A.; Schaffner I.; Mlynek G.; Krutzler M.; Stadlmayr G.; Pirker K. F.; Obinger C.; Daims H.; Djinović-Carugo K.; Furtmüller P. G. (2015) Structure and heme-binding properties of HemQ (chlorite dismutase-like protein) from Listeria monocytogenes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 574, 36–48. 10.1016/j.abb.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofbauer S.; Mlynek G.; Milazzo L.; Puhringer D.; Maresch D.; Schaffner I.; Furtmüller P. G.; Smulevich G.; Djinovic-Carugo K.; Obinger C. (2016) Hydrogen peroxide-mediated conversion of coproheme to heme b by HemQ-lessons from the first crystal structure and kinetic studies.. FEBS J. 283, 4386–4401. 10.1111/febs.13930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofbauer S.; Dalla Sega M.; Scheiblbrandner S.; Jandova Z.; Schaffner I.; Mlynek G.; Djinovic-Carugo K.; Battistuzzi G.; Furtmüller P. G.; Oostenbrink C.; Obinger C. (2016) Chemistry and Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Heme b-HemQ and Coproheme-HemQ.. Biochemistry 55, 5398–5412. 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celis A. I.; Streit B. R.; Moraski G. C.; Kant R.; Lash T. D.; Lukat-Rodgers G. S.; Rodgers K. R.; DuBois J. L. (2015) Unusual Peroxide-Dependent, Heme-Transforming Reaction Catalyzed by HemQ. Biochemistry 54, 4022–4032. 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celis A. I.; Gauss G. H.; Streit B. R.; Shisler K.; Moraski G. C.; Rodgers K. R.; Lukat-Rodgers G. S.; Peters J. W.; DuBois J. L. (2017) Structure-Based Mechanism for Oxidative Decarboxylation Reactions Mediated by Amino Acids and Heme Propionates in Coproheme Decarboxylase (HemQ). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 1900–1911. 10.1021/jacs.6b11324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streit B. R.; Celis A. I.; Shisler K.; Rodgers K. R.; Lukat-Rodgers G. S.; DuBois J. L. (2017) Reactions of Ferrous Coproheme Decarboxylase (HemQ) with O2 and H2O2 Yield Ferric Heme b. Biochemistry 56, 189–201. 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hough M. A.; Andrew C. R. (2015) Cytochromes c’: Structure, Reactivity and Relevance to Haem-Based Gas Sensing. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 67, 1–84. 10.1016/bs.ampbs.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smulevich G.; Feis A.; Howes B. D. (2005) Fifteen years of Raman spectroscopy of engineered heme containing peroxidases: what have we learned?. Acc. Chem. Res. 38, 433–440. 10.1021/ar020112q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smulevich G., Howes B. D., and Droghetti E. (2016) Structural and Functional Properties of Heme-containing Peroxidases: a Resonance Raman Perspective for the Superfamily of Plant, Fungal and Bacterial Peroxidases, In Heme Peroxidases (Raven E., and Dunford B., Eds.), pp 61–98, The Royal Society of Chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- Zámocký M.; Hofbauer S.; Schaffner I.; Gasselhuber B.; Nicolussi A.; Soudi M.; Pirker K. F.; Furtmüller P. G.; Obinger C. (2015) Independent evolution of four heme peroxidase superfamilies. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 574, 108–119. 10.1016/j.abb.2014.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teale F. W. (1959) Cleavage of the haem-protein link by acid methylethylketone. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 35, 543. 10.1016/0006-3002(59)90407-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le P.; Zhao J.; Franzen S. (2014) Correlation of heme binding affinity and enzyme kinetics of dehaloperoxidase. Biochemistry 53, 6863–6877. 10.1021/bi5005975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll S.; Schweiger A. (2006) EasySpin, a comprehensive software package for spectral simulation and analysis in EPR. J. Magn. Reson. 178, 42–55. 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peisach J.; Blumberg W. E.; Ogawa S.; Rachmilewitz E. A.; Oltzik R. (1971) The effects of protein conformation on the heme symmetry in high spin ferric heme proteins as studied by electron paramagnetic resonance,. J. Biol. Chem. 246, 3342–3355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aasa R.; Vänngard T. (1975) EPR signal intensity and powder shapes. Reexamination. J. Magn. Reson. 19, 308–315. 10.1016/0022-2364(75)90045-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson D. P.; Kiesow L. A. (1972) Enthalpy of decomposition of hydrogen peroxide by catalase at 25 degrees C (with molar extinction coefficients of H 2 O 2 solutions in the UV). Anal. Biochem. 49, 474–478. 10.1016/0003-2697(72)90451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler T. J.; Davey C. A.; Fenna R. E. (2000) X-ray crystal structure and characterization of halide-binding sites of human myeloperoxidase at 1.8 A resolution. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 11964–11971. 10.1074/jbc.275.16.11964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zederbauer M.; Furtmüller P. G.; Ganster B.; Moguilevsky N.; Obinger C. (2007) The vinyl-sulfonium bond in human myeloperoxidase: impact on compound I formation and reduction by halides and thiocyanate,. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 356, 450–456. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.02.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogioni S.; Stampler J.; Furtmüller P. G.; Feis A.; Obinger C.; Smulevich G. (2008) The role of the sulfonium linkage in the stabilization of the ferrous form of myeloperoxidase: a comparison with lactoperoxidase,. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 1784, 843–849. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battistuzzi G.; Stampler J.; Bellei M.; Vlasits J.; Soudi M.; Furtmüller P. G.; Obinger C. (2011) Influence of the covalent heme-protein bonds on the redox thermodynamics of human myeloperoxidase. Biochemistry 50, 7987–7994. 10.1021/bi2008432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzocchi M.; Smulevich G. (2003) Relationship between heme vinyl conformation and the protein matrix in peroxidases. J. Raman Spectrosc. 34, 725–736. 10.1002/jrs.1037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feis A.; Tofani L.; De Sanctis G.; Coletta M.; Smulevich G. (2007) Multiphasic kinetics of myoglobin/sodium dodecyl sulfate complex formation. Biophys. J. 92, 4078–4087. 10.1529/biophysj.106.100693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S.; Spiro T. G.; Langry K. C.; Smith K. M.; Budd D. L.; La Mar G. N. (1982) Structural correlations and vinyl influences in resonance Raman spectra of protoheme complexes and proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 104, 4345–4351. 10.1021/ja00380a006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Indiani C.; Feis A.; Howes B. D.; Marzocchi M. P.; Smulevich G. (2000) Effect of low temperature on soybean peroxidase: spectroscopic characterization of the quantum-mechanically admixed spin state. J. Inorg. Biochem. 79, 269–274. 10.1016/S0162-0134(99)00156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker F. (1999) Magnetic spectroscopic (EPR, ESEEM, Mossbauer, MCD and NMR) studies of low-spin ferriheme centers and their corresponding heme proteins. Coord. Chem. Rev. 185–6, 471–534. 10.1016/S0010-8545(99)00029-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brautigan D. L.; Feinberg B. A.; Hoffman B. M.; Margoliash E.; Preisach J.; Blumberg W. E. (1977) Multiple low spin forms of the cytochrome c ferrihemochrome. EPR spectra of various eukaryotic and prokaryotic cytochromes c. J. Biol. Chem. 252, 574–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes B. D.; Feis A.; Indiani C.; Marzocchi M. P.; Smulevich G. (2000) Formation of two types of low-spin heme in horseradish peroxidase isoenzyme A2 at low temperature. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 5, 227–235. 10.1007/s007750050367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg W. E.; Peisach J.; Wittenberg B. A.; Wittenberg J. B. (1968) The electronic structure of protoheme proteins. I. An electron paramagnetic resonance and optical study of horseradish peroxidase and its derivatives,. J. Biol. Chem. 243, 1854–1862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams-Smith D. L.; Bray R. C.; Barber M. J.; Tsopanakis A. D.; Vincent S. P. (1977) Changes in apparent pH on freezing aqueous buffer solutions and their relevance to biochemical electron-paramagnetic-resonance spectroscopy. Biochem. J. 167, 593–600. 10.1042/bj1670593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiro T. G.; Wasbotten I. H. (2005) CO as a vibrational probe of heme protein active sites. J. Inorg. Biochem. 99, 34–44. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips G.; Teodoro M.; Li T.; Smith B.; Olson J. (1999) Bound CO is a molecular probe of electrostatic potential in the distal pocket of myoglobin. J. Phys. Chem. B 103, 8817–8829. 10.1021/jp9918205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ye X.; Yu A.; Georgiev G. Y.; Gruia F.; Ionascu D.; Cao W.; Sage J. T.; Champion P. M. (2005) CO rebinding to protoheme: investigations of the proximal and distal contributions to the geminate rebinding barrier. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 5854–5861. 10.1021/ja042365f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel K.; Kozlowski P.; Zgierski M.; Spiro T. (2000) Role of the axial ligand in heme-CO backbonding; DFT analysis of vibrational data. Inorg. Chim. Acta 297, 11–17. 10.1016/S0020-1693(99)00253-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ray G.; Li X.; Ibers J.; Sessler J.; Spiro T. (1994) How far can proteins bend the FeCO unit. - Distal polar and steric effects in heme proteins and models. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116, 162–176. 10.1021/ja00080a019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howes B. D.; Helbo S.; Fago A.; Smulevich G. (2012) Insights into the anomalous heme pocket of rainbow trout myoglobin. J. Inorg. Biochem. 109, 1–8. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morikis D.; Champion P.; Springer B.; Sligar S. (1989) Resonance Raman investigations of site-directed mutants of Myoglobin - Effects of distal Histidine replacement. Biochemistry 28, 4791–4800. 10.1021/bi00437a041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smulevich G.; Mantini A. R.; Paoli M.; Coletta M.; Geraci G. (1995) Resonance Raman studies of the heme active site of the homodimeric myoglobin from Nassa mutabilis: a peculiar case. Biochemistry 34, 7507–7516. 10.1021/bi00022a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao S.; Ishikawa H.; Yamada T.; Mizutani Y.; Hirota S. (2015) Carbon monoxide binding properties of domain-swapped dimeric myoglobin. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 20, 523–530. 10.1007/s00775-014-1236-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe C. L.; Ott M.; Patel N.; Singh K.; Mistry S. C.; Goff H. M.; Raven E. L. (2004) Autocatalytic formation of green heme: evidence for H2O2-dependent formation of a covalent methionine-heme linkage in ascorbate peroxidase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 16242–16248. 10.1021/ja048242c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon J. R.; Heinrichs D. E. (2015) Recent developments in understanding the iron acquisition strategies of gram positive pathogens. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 39, 592–630. 10.1093/femsre/fuv009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geeraerts Z.; Celis A. I.; Mayfield J. A.; Lorenz M.; Rodgers K. R.; DuBois J. L.; Lukat-Rodgers G. S. (2018) Distinguishing active site characteristics of chlorite dismutases with their cyanide complexes. Biochemistry 57, 1501–1516. 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b01278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geeraerts Z.; Rodgers K. R.; DuBois J. L.; Lukat-Rodgers G. S. (2017) Active Sites of O2-Evolving Chlorite Dismutases Probed by Halides and Hydroxides and New Iron-Ligand Vibrational Correlations. Biochemistry 56, 4509–4524. 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffner I.; Mlynek G.; Flego N.; Pühringer D.; Libiseller-Egger J.; Coates L.; Hofbauer S.; Bellei M.; Furtmüller P. G.; Battistuzzi G.; Smulevich G.; Djinovic-Carugo K.; Obinger C. (2017) Molecular Mechanism of Enzymatic Chlorite Detoxification: Insights from Structural and Kinetic Studies. ACS Catal. 7, 7962–7976. 10.1021/acscatal.7b01749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofbauer S.; Gruber C.; Pirker K. F.; Sündermann A.; Schaffner I.; Jakopitsch C.; Oostenbrink C.; Furtmüller P. G.; Obinger C. (2014) Transiently produced hypochlorite is responsible for the irreversible inhibition of chlorite dismutase. Biochemistry 53, 3145–3157. 10.1021/bi500401k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.