Hydrogen gas (H2) is an essential element for microbes that inhabit anaerobic environments. H2 production acts to recycle electrons that accumulate during fermentation, whereas oxidation of H2 liberates those reducing equivalents and couples them to reactions that drive metabolism. Biological H2 metabolism and the interspecies transfer of H2 are of principal importance to the maintenance of energetic processes within microbial systems, and as such, [FeFe]- and [NiFe]-hydrogenase enzymes can be viewed as fundamental components of energy transduction pathways in biology.1

[FeFe]-hydrogenase (HydA), in particular, has been the focus of considerable biochemical analyses given its tendency to generate molecular H2 at turnover rates that approximate 20000 events per second.2 The catalytic prowess of HydA makes this enzyme and its catalytic cluster, termed the H-cluster, fascinating targets for the development of biohydrogen production technologies and biohybrid devices. The promise of such technological advances to enable movement away from traditional fossil fuels underscores the importance of unravelling the complex mechanisms of H-cluster assembly and hydrogen catalysis in HydA.

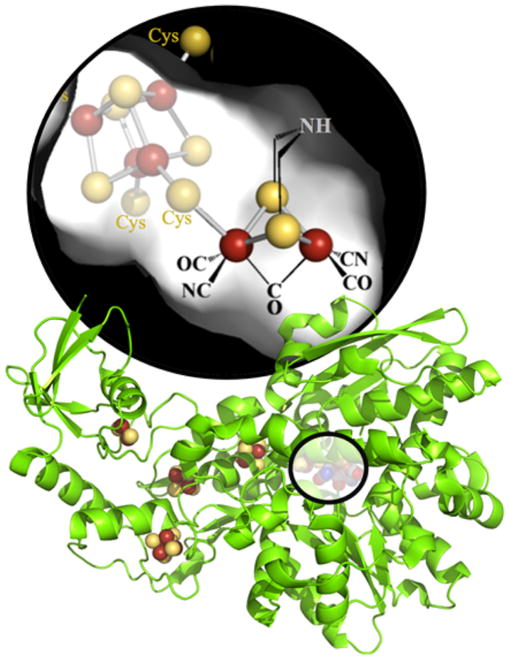

The catalytic H-cluster in HydA is an unusual modified iron–sulfur cluster that consists of a [4Fe-4S] cubane ([4Fe-4S]H) bridged through a cysteine thiolate to an organometallic 2Fe subcluster ([2Fe]H) that contains three carbon monoxides (CO), two cyanides (CN–), and a bridging dithiomethylamine (DTMA) as ligands (Figure 1). While the general iron–sulfur cluster assembly machinery, such as the Isc and Suf protein systems, can synthesize the [4Fe-4S]H cluster, construction of [2Fe]H requires specialized machinery provided by the hydrogenase accessory proteins HydE, HydF, and HydG. HydE and HydG are members of the radical S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) superfamily; these enzymes coordinate a site-differentiated [4Fe-4S] cluster that promotes the coordination and reductive cleavage of SAM.3 HydE is believed to be responsible for DTMA synthesis, although both its substrate and its reaction mechanism are currently unresolved. HydG, on the other hand, is known to catalyze the conversion of tyrosine into p-cresol, and the CO and CN− that become [2Fe]H cluster ligands (see ref 3 and references cited therein). The GTPase HydF is a scaffold or carrier for the [2Fe]H cluster.

Figure 1.

[FeFe]-hydrogenase from Clostridium pasteurianum I (CpI) (PDB ID: 3C8Y). The H-cluster, magnified at the top, is located in HydA, as highlighted by the overlay on the green ribbon cartoon of the crystal structure. The accessory iron–sulfur clusters and the H-cluster are shown as spheres, with iron colored rust and sulfur colored yellow.

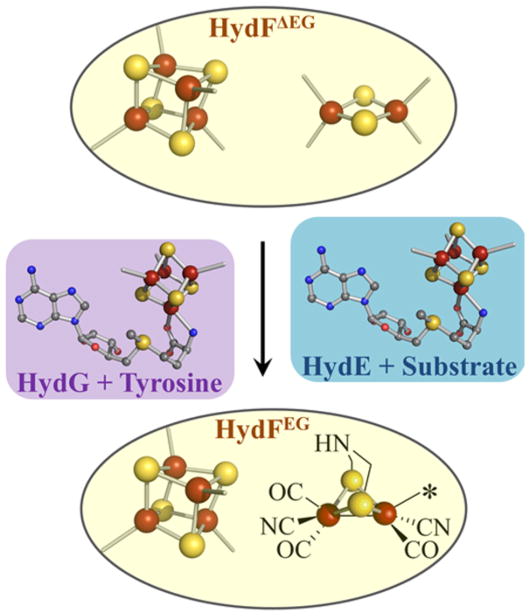

This third player in the H-cluster biosynthetic pathway, HydF, when co-expressed with HydE and HydG (HydFEG) results in Fourier transform infrared vibrational spectra consistent with Fe–CO and Fe–CN− species bound to the protein (see ref 3 and references cited therein). Importantly, while expression of HydF by itself (HydFΔEG) is not capable of affecting maturation of HydA when HydA is expressed in the absence of HydE, HydF, and HydG (HydAΔEFG), HydFEG does promote the in vitro activation of HydAΔEFG (see ref 3 and references cited therein). As HydAΔEFG is known to coordinate only the [4Fe-4S]H component of the H-cluster, together these results point to assembly and delivery of the [2Fe]H cluster by HydFEG (Figure 2). While this biochemical evidence provides support for the central role of HydF in H-cluster maturation, it does not establish whether this protein acts as a scaffold (wherein the [2Fe]H cluster is synthesized on HydF) or carrier (wherein HydF accepts a preassembled [2Fe]H cluster) during maturation.

Figure 2.

Hypothetical maturation scheme depicting [2Fe]H assembly on HydF. Spectroscopic results provide precedence for the [4Fe-4S], [2Fe-2S], and [2Fe]H cluster states associated with HydFΔEG and HydFEG. SAM is shown coordinated to the site-differentiated [4Fe-4S] cluster in both HydG and HydE. The color scheme in this figure is as follows: iron, rust; sulfur, yellow; nitrogen, blue; oxygen, red; carbon, gray.

A critical determinant in clarifying the function of HydF relates to establishing the iron–sulfur cluster states that are associated with it prior to its loading by HydE and HydG (HydFΔEG). While preliminary work provided spectroscopic evidence for both [2Fe-2S]2+/+ and [4Fe-4S]2+/+ clusters being associated with HydFΔEG, subsequent studies of HydFΔEG challenged the existence of a [2Fe-2S] cluster. These discrepancies led to our recent reexamination of this issue.4 We assessed iron–sulfur cluster spectroscopic features and followed changes to the quaternary structure in HydFΔEG as a function of sample handling. Our analysis demonstrates that freshly purified, as-isolated, and chemically reconstituted HydFΔEG preparations all coordinate a [2Fe-2S]2+/+ cluster, with the 1+ state giving rise to the g ~ 2 electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) signal commonly observed in HydFΔEG.4 Moreover, we determined that the [2Fe-2S]2+/+ cluster signal intensity can be affected both by the use of a reducing agent (dithiothreitol, dithionite, or deazariboflavin-mediated photo-reduction) and by sample handling. Midpoint potentiometric experiments provided estimates for the [2Fe-2S]2+/+ (Em ≥ −200 mV) and [4Fe-4S]2+/+ (Em = −368 mV) cluster redox potentials, which were consistent with the observation that strong reducing agents caused conversion of [2Fe-2S]+ clusters to a diamagnetic state, concomitant with the production and signal intensification of [4Fe-4S]+ cluster signals (Figure 2).4 Outstanding questions from this work4 related to the proximity of the [4Fe-4S]+ and [2Fe-2S]+ clusters and whether the dimer and tetramer oligomeric states coordinate distinct iron–sulfur cluster species. Insight into these issues was gained via the analysis of spin relaxation times using pulsed EPR in HydFΔEG samples exhibiting both [4Fe-4S]+ and [2Fe-2S]+ cluster EPR signals.5 Simulations of relaxation rates established that the HydFΔEG [2Fe-2S]+ cluster is not near, or directly bridged to, the [4Fe-4S]+ cluster. As these HydFΔEG samples were predominantly dimeric in nature, this suggests that the [2Fe-2S]+ and [4Fe-4S]+ clusters are coordinated within different monomeric subunits of the dimer at a distance of ≥ 25 Å, or one population of dimeric HydFΔEG contains only the [2Fe-2S]+ cluster while another population of the dimeric enzyme contains only the [4Fe-4S]+ cluster. While the [2Fe-2S] cluster ligand environment in HydF is undetermined, our results suggest that conserved CXHX46–53CXXC motif residues coordinate the cluster. Examining the biosynthetic role of this HydF, we show that dimeric HydFEG productively interacts with HydAΔEFG and transfers the [2Fe]H cluster to afford HydA activation.5 Together, the observations indicate a specific role for the HydF dimer in the H-cluster biosynthetic pathway.

These results demonstrate that prior to interacting with HydE and HydG, HydFΔEG is primarily dimeric and binds redox active [4Fe-4S] and [2Fe-2S] clusters; however, these iron–sulfur clusters are not poised to create an H-cluster-like 6Fe species upon delivery of ligands by HydE and HydG. It is clear that additional work is required to better comprehend the maturation steps pertaining to how and in what order HydE and HydG interact with HydF, and what, specifically, each radical SAM enzyme delivers to HydF. Regardless, the definitive observation of a redox active [2Fe-2S] cluster on HydFΔEG provides a foundation for understanding the role that this cluster may play in the maturation of the [2Fe]H-coordinated HydFEG dimer state.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Our work on [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturation is supported by U.S. Department of Energy Grant DE-FG02-10ER16194 (to J.B.B. and E.M.S.).

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Peters JW, Schut GJ, Boyd ES, Mulder DW, Shepard EM, Broderick JB, King PW, Adams MW. [FeFe]-and [NiFe]-hydrogenase diversity, mechanism, and maturation. Biochim Biophys Acta, Mol Cell Res. 2015;1853:1350–1369. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Madden C, Vaughn MD, Diez-Perez I, Brown KA, King PW, Gust D, Moore AL, Moore TA. Catalytic turnover of [FeFe]-hydrogenase based on single-molecule imaging. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:1577–1582. doi: 10.1021/ja207461t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shepard EM, Mus F, Betz JN, Byer AS, Duffus BR, Peters JW, Broderick JB. [FeFe]-Hydrogenase Maturation. Biochemistry. 2014;53:4090–4104. doi: 10.1021/bi500210x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shepard EM, Byer AS, Betz JN, Peters JW, Broderick JB. A Redox Active [2Fe-2S] Cluster on the Hydrogenase Maturase HydF. Biochemistry. 2016;55:3514–3527. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shepard EM, Byer AS, Aggarwal P, Betz JN, Scott AG, Shisler K, Usselman RJ, Eaton GR, Eaton SS, Broderick JB. Electron Spin Relaxation and Biochemical Characterization of the Hydrogenase Maturase HydF: Insights into [2Fe-2S] and [4Fe-4S] Cluster Communication and Hydrogenase Activation. Biochemistry. 2017;56:3234–3247. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]