Abstract

Value, like beauty, exists in the eye of the beholder. This article places the value of clinical sleep medicine services in historical context and presents a vision for the value-based sleep of the future. First, the history of value and payment in sleep medicine is reviewed from the early days of the field, to innovative disruption, to the widespread adoption of home sleep apnea testing. Next, the importance of economic perspective is discussed, with emphasis on cost containment and cost-shifting between payers, employers, providers, and patients. Specific recommendations are made for sleep medicine providers and the field at large to maximize the perceived value of sleep. Finally, alternate payment models and value-based care are presented, with an eye toward the future for clinical service providers as well as integrated health delivery networks.

Citation:

Wickwire EM, Verma T. Value and payment in sleep medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(5):881–884.

Keywords: alternative payment models, health economics, home sleep apnea tests, population health, value-based medicine

HISTORY OF VALUE AND PAYMENT IN SLEEP MEDICINE

According to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, more than 2,000 sleep centers were accredited between the years 1977 and 2000 in the United States.1 In addition to the confluence of rising obesity rates and increasing awareness regarding sleep disorders, the primary economic driver of this remarkable growth was the profitability of the attended polysomnography (PSG). For example, between the years 2005 and 2011, Medicare payments for PSG services increased 39%, from $407 million to $565 million.2 From the perspective of the health care system or sleep specialist, this laboratory-based testing system was highly efficient, providing reliably accurate diagnoses, substantial revenue, and profitable growth. However, from the perspective of federal and private payers, sleep testing services represented a rapidly increasing cost with an uncertain return on investment. Not surprisingly, commercial insurance payers began to seek ways to reduce costs in sleep medicine, resulting in the widespread adoption of home sleep apnea tests (HSATs). From the perspective of the health care system or provider, the use of HSATs has negatively affected, at minimum, profitability. But from the payer perspective, the advent of HSAT has been highly valuable, resulting in increased efficiency and substantial cost savings. As has been seen in other marketplaces following disruptive innovation, HSAT technology will continue to improve over time and capture increased market share.3,4

VALUE IS IN THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER: PERSPECTIVE IN HEALTH ECONOMIC EVALUATIONS

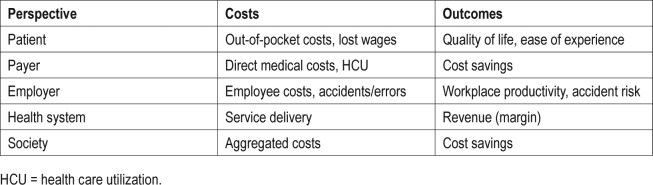

Like beauty, value exists in the eye of the beholder. Thus, perspective is foundational to health economic evaluations designed to measure value. Depending on the research question of interest, health economic studies can be designed, performed, and interpreted from a range of perspectives such as the patient perspective, payer perspective, employer perspective, health system perspective, or societal perspective (see Table 1). Each possible perspective weighs costs and emphasizes outcomes of interest to the specified stakeholders (see Table 1). Because of these differences in costs and outcomes, a given procedure—HSAT, for example—can be highly cost-effective from one perspective but cost-ineffective from another. As sleep medicine seeks to define, demonstrate, and maximize its value to diverse stakeholders, the importance of appreciating these multiple perspectives and points of view cannot be overstated. After all, sleep services are reimbursed based on the value perceived by others outside the sleep community.

Table 1.

Common perspectives, costs, and outcomes in health economic evaluations.

HEALTH INSUR ANCE PLANS ARE DIFFERENTIATED BY FINANCIAL RISK

Currently, most insured individuals in the United States participate in an employer-sponsored health plan. Beyond features and benefits, these plans are distinguished primarily by the level of financial risk to the employer or plan sponsor. At one end of the spectrum, self-funded or administrative services only plans represent the greatest level of risk to the employer, with minimal risk to the insurance company. In exchange for this risk, the employer receives the greatest control over design and administration of the plan—but they are also liable for the variable costs of health services delivered to beneficiaries. Highly customized plans are subject to federal and state regulations and typically developed in conjunction with an insurance company, which subsequently performs all administrative functions in support of the plan (eg, processing claims and payments). To protect against catastrophic loss, self-insured employers may also purchase stop-loss insurance. Because of the potential for cost savings, an increasing number of large employers (ie, > 1,000 employees) are self-funding health plans for their employees.5 At the other end of the risk spectrum, fully insured plans represent the lowest level of risk to the employer. In exchange for this reduced risk, employers lose control over details of the plan, instead selecting from a fixed menu of plans designed and administered by an insurance company. Employer costs are fixed based on the number of employees and dependents covered. The insurance company is financially responsible for claims submitted and pays claims based on the benefit design of the policy.

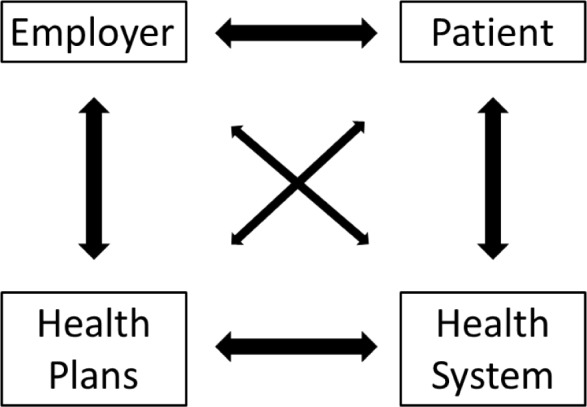

COST-SHIFTING AND COST CONTAINMENT

From the payer perspective, cost savings is the key health economic outcome. Thus, payers and plan sponsors (ie, employers) employ multiple strategies to reduce costs. At the level of plan design, high-deductible plans have been developed, which seek to transfer risk and “cost-shift” to the covered beneficiary (see Figure 1). For example, a health savings account (HSA) typically does not pay claims until the individual or family has met a predetermined annual deductible, which is usually high (eg, $3,000). In exchange for these higher deductibles, beneficiaries incur reduced up-front costs because the annual premiums tend to be lower than premiums for fully insured plans, which explains why such plans are typically preferred by healthier individuals. Deductible expenses and co-pays can be paid from the HSA, which is controlled by the employee or covered beneficiary. The Internal Revenue Service establishes annual limits for pre-tax contributions to an HSA (eg, $3,400 per individual or $6,750 per family in 2017, with amounts increased by $1,000 for individuals older than 65 years).

Figure 1. Cost shifting and transfer of risk among stakeholders.

Health plans are differentiated primarily by financial risk to the employer or plan sponsor, and the insurance company. In effort to reduce costs, employers and payers seek to “cost shift” expenses to patients and health providers.

In addition to plan design and cost shifting, employers and plan sponsors frequently require verification of medical necessity for high-cost and/or high-volume procedures. Broadly speaking, these efforts to contain costs are considered utilization management (UM), and administration of UM programs can be managed internally by a payer or outsourced to a third-party UM vendor. In sleep medicine, UM efforts to date have focused on reducing spending associated with diagnostic testing by requiring preauthorization for in-laboratory PSG. As sleep specialists are well aware, most health plans consider attended PSG medically necessary only in the presence of significant medical comorbidity. Further, although certain suspected sleep diagnoses warrant attended PSG, it is important to realize that from the payer perspective, occult obstructive sleep apnea can exacerbate symptoms of many these other sleep disorders (eg, parasomnias, limb movements, and hypersomnias). Thus, an HSAT is frequently required to rule out obstructive sleep apnea even when other sleep disorders are suspected. Health plan sleep policies are edited and revised regularly, typically yearly.

HSAT: RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PROVIDERS

From the provider perspective, the single greatest change to the practice of sleep medicine has been the rapid adoption of HSAT. At the same time that HSAT has reduced costs for payers, HSAT has reduced revenues for providers. This has radically altered the way in which sleep medicine is practiced and in certain regions challenged the viability of sleep medicine itself.6 In addition to transitioning diagnostic testing from PSG to HSAT, sleep medicine providers have experienced a dramatic increase in administrative burden associated with preauthorization documentation for both PSG and HSAT. Although sleep medicine providers would benefit from guidance regarding standardized workflow and preauthorization procedures, inconsistent policies across payers make actionable recommendations difficult. Further, payers vary widely in their adherence to American Academy of Sleep Medicine practice parameters and clinical guidelines. There is a dramatic need for a central or standardized repository of payer policies to reduce provider administrative burden and to guide health care consumers in evaluating sleep coverage of insurance plans.

Despite these inconsistencies, several recommendations can be made to improve workflow, increase efficiency, and provide optimal sleep medicine care. First, sleep providers must stay up to date regarding the policies of each payer with whom they work. Each payer will provide a list of specific requirements and associated clinical documentation for preauthorization of PSG or HSAT—the more closely these guidelines are followed, the smoother the preauthorization process will be. When policies are unclear (eg, indications for attended versus at-home titration), written guidance from payers and monitor updates should be requested. Second, sleep providers should strive to build relationships with the peer reviewers employed by payers. Because peer reviewers are not required by law to be sub-specialists, many peer reviewers have limited understanding of sleep disorders testing or treatment. Nonetheless, establishing collegial working relationships and educating peer reviewers regarding sleep and sleep disorders can go a long way. Sleep medicine providers should be straightforward and provide accurate information based on unambiguous clinical documentation. Third, when adverse outcomes are reached via peer review, sleep providers and patients can also appeal payer decisions. Payers are highly regulated and can suffer regulatory consequences for high numbers of number of appeals. Fourth, sleep medicine providers have strength in numbers. In other areas of medicine, practice groups are increasingly joining forces to negotiate more favorable contractual terms. Finally, it should be noted that patients are increasingly motivated to use social media to voice dissatisfaction with businesses, including insurance payers. Of course, social media can be a double-edged sword and presents its own challenges.

EMERGING ALTERNATE PAYMENT MODELS SUPPORT VALUE-BASED CARE

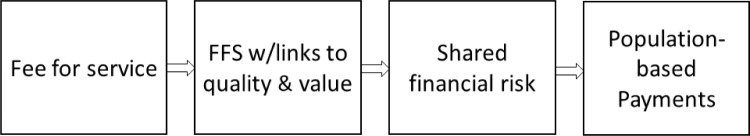

New payment models are required to encourage and support the transition from volume-based fee for service to value-based care. Therefore, diverse stakeholders including policymakers, payers, and provider health systems are heavily invested in the development and implementation of alternate payment models (APMs). Indeed, various APMs have already been implemented and are affecting the way that patients are referred, the manner in which the diagnosis is made, and methods of treatment in primary care and specialty settings. Although a detailed presentation of various APMs is beyond the scope of this article, readers are referred to the excellent APM Framework produced by the multi-stakeholder Health Care Payment & Learning Action Network for further insight7 (see Figure 2). Within this framework, payment models exist along with a value-based continuum ranging from fee for service not linked to quality or value (Category 1) to patient-centered, population-based payments delivered to integrated finance and health delivery systems (ie, joint insurance payer and health systems; Category 4). Midpoints along the continuum represent steps toward value-based care, with payments for increasing provider accountability, such as foundational payments for operational infrastructure (health information technology), bonus payments for value-based practices (reporting and performance), and shared financial risk (portion of payment is based on realized cost savings). In sleep medicine, the effect of APMs will vary depending on practice location (rural versus urban) and practice setting (small group versus large health system), which affect not only supply and demand but also financial infrastructure and economy of scale.

Figure 2. The transition from volume to value.

Alternate payment models seek to increase value by moving from volume-based fee-for-service (FFS) payments to value-based care. Beginning with the status quo, sequential steps first link FFS payments to indicators of quality and value, then share financial risk, and finally provide fixed payments for managing population health.

THE FUTURE IS NOW: HOW TO MA XIMIZE VALUE AND PAYMENT IN SLEEP MEDICINE

The need for sleep medicine services has never been greater.

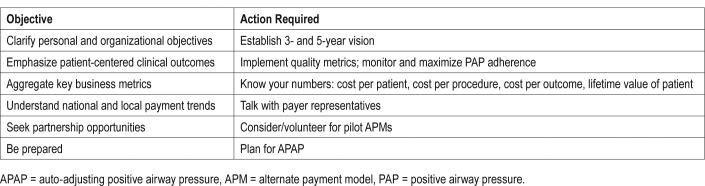

However, sleep medicine providers must adapt and adjust in order to survive and thrive within a new framework of patient-centered care and value-based payments. Table 2 presents actionable recommendations for practitioners and organizational leaders. This will require greater familiarity with payment trends including APMs and a dramatic increase in data-driven decision-making based on costs and patient-centered outcomes. Regardless of practice setting or location, fast-paced change is underway and will dramatically affect the way that sleep medicine is practiced and reimbursed.

Table 2.

Recommendations for sleep specialists.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors have seen and approved this manuscript. Dr. Wickwire's institution has received research funding from Merck, ResMed, and the American Sleep Medicine Foundation. He has moderated non-commercial scientific discussion and consulted for Merck and is an equity shareholder in WellTap. Dr. Verma is an employee of Tufts Health Plan. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of Tufts Health Plan.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Accreditation Growth: More than 2,000 Sleep Centers and Labs Now Accredited. American Academy of Sleep Medicine website. [Accessed July 23, 2017]. https://aasm.org/aasm-accreditation-growth-more-than-2000-sleep-centers-and-labs-now-accredited. Published May 27, 2010.

- 2.United States Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2013. Questionable billing for polysomnography services. Report No. OEI-05-12-00340. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bower JL, Christensen CM. Disruptive technologies: Catching the wave. J Prod Innova Manag. 1996;1(13):75–76. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christensen CM, Raynor ME, McDonald R. Disruptive innovation. Harv Bus Rev. 2015;93(12):44–53. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fronstin P. Self-insured health plans: State variation and recent trends by firm size. EBRI Notes. 2012;33(11):2–10. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quan SF, Epstein LJ. A warning shot across the bow: the changing face of sleep medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9(4):301–302. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Health Care Payment and Learning Action Network. Alternative Payment Model (APM) Framework Refresh. [Accessed July 23, 2017]. Health Care Payment and Learning Action Network website https://hcp-lan.org/groups/apm-refresh-white-paper. Published July 11, 2017.