Abstract

Background

Currently, no pharmacogenetic tests for selecting an opioid dependence pharmacotherapy have been approved by the FDA.

Objectives

Determine the effects of variants in 11 genes on dropout rate and dose in patients receiving methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00315341).

Methods

Variants in 6 pharmacokinetic genes (CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, CYP3A4) and 5 pharmacodynamic genes (HTR2A, OPRM1, ADRA2A, COMT, SLC6A4) were genotyped in samples from a 24-week, randomized, open-label trial of methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone for the treatment of opioid dependence (n = 764; 68.7% male). Genotypes were then used to determine the metabolism phenotype for each pharmacokinetic gene. Phenotypes or genotypes for each gene were analyzed for association with dropout rate and mean dose.

Results

Genotype for 5-HTTLPR in the SLC6A4 gene was nominally associated with dropout rate when the methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone groups were combined. When the most significant variants associated with dropout rate were analyzed using pairwise analyses, SLC6A4 (5-HTTLPR) and COMT (Val158Met; rs4860) had nominally significant associations with dropout rate in methadone patients. None of the genes analyzed in the study were associated with mean dose of methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone.

Conclusions

This study suggests that functional polymorphisms related to synaptic dopamine or serotonin levels may predict dropout rates during methadone treatment. Patients with the S/S genotype at 5-HTTLPR in SLC6A4 or the Val/Val genotype at Val158Met in COMT may require additional treatment to improve their chances of completing addiction treatment. Replication in other methadone patient populations will be necessary to ensure the validity of these findings.

Keywords: Opioid dependence, methadone, buprenorphine, pharmacogenetics, COMT, SERT

Introduction

Opioid dependence is an ongoing health crisis in many parts of the world and millions of individuals in the United States are currently using prescription opioid analgesics for non-medical reasons or heroin (National Survey on Drug Use and Health). The number of opioid-related overdose deaths in the United States has almost quadrupled over the last decade (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Data across a large number of studies reveal that many patients with opioid dependence continue illicit opioid use despite being enrolled in a methadone or buprenorphine treatment program (1). An additional subset of patients drops out of the program and likely relapses as well.

Pharmacological treatments for psychiatric disorders, including substance use disorder, can have high rates of failure (e.g. relapse and/or dropout), resulting in significant costs to both patients and society. This is true of both methadone and buprenorphine, two opioid agonists used in the treatment of opioid dependence (1). Understanding the factors that predict effective opioid dependence treatment is essential so that individuals with high-risk of treatment failure may be identified and alternative or additional treatment and support options may be provided to them.

Opioid dependence treatment outcome is a complex trait that is dependent on both genetic and environmental components, as well as gene-environment interactions (2–4). Socioeconomic measurements, such as employment status and education level, and factors such as peer groups and relationship stability are strong predictors of treatment outcome (3). Co-morbidities such as depression have also been correlated with continued drug use during opioid dependence treatment (3, 5, 6). In contrast to these environmental and co-morbid factors, there has been little success identifying genetic variants that predict the efficacy of pharmacological addiction treatments. This lack of confirmed pharmacogenetic markers is the result of studies with relatively small sample size, lack of independent populations for replication studies, and the polygenic natures of both addiction and response to addiction pharmacotherapy.

Pharmacogenetic variants can be broadly defined as either pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic in nature. Pharmacokinetic variants affect the bioavailability of the medication in the body, while pharmacodynamic variants directly or indirectly alter the downstream effects of the medication. The CYP450 gene family encodes enzymes that metabolize a wide variety of compounds, including many opioids. Buprenorphine is primarily metabolized by CYP3A4 but little is known about the effects of CYP3A4 status on required dose or outcomes in buprenorphine patients (7). In vitro experiments suggest the possibility of minor roles for other enzymes including CYP2C9 and CYP1A2 as well (8, 9). In contrast, methadone is primarily metabolized by CYP2B6. Additional evidence indicates that CYP2D6, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4 can also metabolize this medication to varying degrees (10–13). Polymorphisms in all four genes alter the metabolism rate of the resulting enzymes and may affect methadone pharmacokinetics. Genetic variants of CYP2B6 are associated with plasma concentrations of methadone and CYP2B6 or CYP2C19 genotypes have been shown in recent studies to predict stabilized methadone doses, although earlier research on CYP2B6 did not observe such an association (10, 14–19). One study suggests that CYP3A4 genotype may also be associated with withdrawal symptoms and adverse reactions in methadone maintenance populations (20). Some non-enzyme proteins can also affect bioavailability; a variant in ABCB1, which encodes a drug efflux pump, has been associated with methadone dose and plasma concentration (10, 14).

In contrast to pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics is a broader category covering genes that may affect medication response. A small number of pharmacodynamic variants have been identified in opioid dependence treatment. Variants in ARRB2 and DRD2 were found to be associated with methadone response in a European cohort (21). Since ARRB2 regulates internalization of the mu-opioid receptor, the primary target of methadone, and dopamine is released downstream of opioid signaling, both genes are logical pharmacogenetic candidates for the medication (22). Polymorphisms in intron 1 of OPRD1 have also been linked to treatment outcome on methadone and buprenorphine (2, 4). The biological mechanisms underlying these effects are less clear since the classical targets of these medications are the mu- and kappa-opioid receptors rather than the delta-opioid receptor, although mu-delta receptor dimers may be involved (23). A common non-synonymous variant in OPRM1 (rs1799971) is another likely candidate for pharmacodynamics effects on opioid dependence treatment, although a previous study found no association (24). Additional candidates are functional variants in genes connected to depression/anxiety (e.g. COMT, SLC6A4, HTR2A) or ADHD (e.g. ADRA2A). These psychiatric disorders been shown to negatively affect opioid dependence treatment outcomes (3, 6, 25). To date, no pharmacogenetic findings in opioid dependence treatment have been successfully replicated and the FDA has not approved any pharmacogenetic tests for selecting an opioid dependence medication.

The Starting Treatment with Agonist Replacement Therapy (START) clinical trial was a 24-week, randomized, open-label trial of methadone and Suboxone® (buprenorphine/naloxone) for the treatment of opioid dependence and was conducted through the National Institute on Drug Abuse’s Clinical Trials Network. To determine the effect of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic genes on opioid dependence treatment, we analyzed the START samples with Assurex Health GeneSight® Analgesic, Psychotropic and ADHD panels and analyzed the association between genotype and both dropout rate and mean dose. This study includes the first reported analyses of several variants, as well as attempted replications of previous findings, with regards to OUD treatment.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Procedures

The demographics, methodology and results for the START trial are described in the main study publication (26). Briefly, opioid dependent patients were recruited for treatment at federally licensed opioid agonist replacement programs in the United States between May 2006 and October 2009. The study was approved by institutional review boards at all participating sites. Participants provided written informed consent for the main START trial and the secondary genetics study. Trial oversight was provided by the NIDA Clinical Trials Network Data Safety and Monitoring Board. All patients were at least 18 years of age and met DSM-IV-TR criteria for opioid dependence. Ethnicity was determined by self-report. Exclusion criteria included: cardiomyopathy, liver disease, acute psychosis, blood levels of alanine amino transferase or aspartate amino transferase greater than 5 times the maximum normal level, and poor venous access. Patients were randomized to 24 weeks of open-label buprenorphine/naloxone (hereafter “buprenorphine”) or methadone treatment.

A flexible dosing approach was used, with dose changes allowed during the study. The initial dose of buprenorphine was 2 to 8mg, which could be increased to 16mg on the first day in the case of persistent withdrawal. The dose could be further increased in subsequent days to a maximum dose of 32mg; the mean daily dose was 16.5 ± 7.2 mg and the mean maximum dose was 24.0 ± 8.2mg. The maximum initial dose of methadone was limited to 30mg, with an additional 10mg allowed on the first day for persistent withdrawal as stipulated by US statute. Methadone could be increased in subsequent days by 10mg increments with no maximum dose. The mean daily methadone dose was 72.8 ± 33.0mg and the mean maximum dose was 95.8 ± 43.1mg. Participants came to the clinic daily for observed dosing except on Sundays and holidays or when take-home medications were permitted by local regulations. Urine samples were tested weekly for the presence of opioids other than the one prescribed. Samples testing positive for methadone were counted as positive for buprenorphine patients, but not for methadone patients.

Genotyping

DNA was extracted from whole blood and stored at −20°C prior to genotyping. Genotyping was performed in batches of 82–95 samples at Assurex Health Laboratory (Mason, Ohio). Polymorphisms were genotyped in 11 genes previously associated with opioid metabolism or efficacy: 6 pharmacokinetic genes (CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, CYP3A4) and 5 pharmacodynamic genes (HTR2A, OPRM1, ADRA2A, COMT, SLC6A4). The serotonin-transporter-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) in the promoter of SLC6A4 was genotyped by the capillary electrophoresis of PCR products on QIAxcel instrument (QIAgene) and genotypes were called using QIAgene Screengel Software 1.2.0 and 1.4.0.0. Analysis of CYP2D6 was completed by using xTAG® kits (Luminex Molecular Diagnostics). All other genes were analyzed using custom xTAG® assays (Luminex Molecular Diagnostics). The following pharmacokinetic genetic variants were genotyped: CYP1A2 −3860G>A, −2467T>delT, −739T>G, −729C>T, −163C>A, 125C>G, 558C>A, 2116G>A, 2473G>A, 2499A>T, 3497G>A, 3533G>A, 5090C>T, 5166G>A, 5347C>T; CYP2B6 *1, *4, *6, *9; CYP2C19 *1, *2, *3, *4, *5, *6, *7, *8, *17; CYP2C9 *1, *2, *3, *4, *5, *6; CYP2D6 *1, *2, *2A, *3, *4, *5, *6, *7, *8, *9, *10, *11, *12, *14, *15, *17, *41, gene duplication; CYP3A4 *1, *13, *15A, *22. The following pharmacodynamic genetic variants were genotyped: HTR2A −1438G>A (rs6311); OPRM1 118A>G (rs1799971); ADRA2A −1291C>G (rs1800544); COMT Val158Met (rs4680). Genotypes for Luminex assays were called using TDAS LMS 2.4 software. CYP450 genotypes were converted to metabolism status phenotypes based on available literature. Initial call rates for all assays were >95%. All uncalled samples were re-genotyped. In total, 761 of 764 samples were successfully genotyped for all analyzed alleles. All biallelic variants were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in both treatment groups (p > 0.05) with the exception of rs1800544 in methadone patients (p = 0.003).

Statistical analysis

Dropout rate was used as the outcome measurement. Dropout was defined as failure to provide a urine drug screen for opioids on the final week of the trial (week 24). The effects of phenotype or genotype of each gene were analyzed for methadone only, for buprenorphine only, and for both medications combined. Dose was used as a covariate in all dropout analyses with subjects binned into quintiles by mean dose. Logistic regression was used to model dropout rate as a function of phenotype for each pharmacokinetic gene. Dropout rate was analyzed using chi-square tests for allelic associations for each pharmacodynamic gene. Mean dose was analyzed independently for each medication separately using one-way ANOVA models, where average dose during the 24-week follow-up period was modeled as a function of phenotype or genotype for each gene. Pairwise comparisons between phenotypes or genotypes of genes were performed. Multiple testing correction was performed using the false discovery rate (FDR) procedure. Statistical significance was defined as p≤0.05 after correction, while nominal significance was defined as p≤0.05 prior to correction. P-values presented in the results are not corrected for multiple testing. SAS v9.4 was used for all analyses.

Due to small numbers of individuals in particular phenotypic or genotypic groups, the following groups were combined for all statistical analyses: CYP1A2 − extensive (n = 344) and intermediate metabolizers (n = 3); CYP3A4 − poor (n = 1) and intermediate metabolizers (n = 73); OPRM1 (rs1799971) − A/G (n = 142) and G/G (n = 8) genotypes.

Results

Population Demographics

Demographic information for the study population is provided in Table 1. The genetics arm of the study only enrolled a subset of the patients who were initially randomized in the START trial (764 of 1,267 patients). Buprenorphine patients in the genetics study were significantly more likely to drop out of the study than methadone patients (Chi-square p=0.001) by Week 24. A similar effect was previously found when analyzing the two medications using the entire randomized population (27). Due to increased dropout rate among buprenorphine patients, randomization was changed during the main START trial from 1:1 (buprenorphine:methadone) to 2:1. To ensure that unequal randomization did not skew the genetic profile of either medication group, the allele frequencies for the pharmacodynamic genes and the phenotype frequencies for the pharmacokinetic genes analyzed in this study were compared between the methadone and buprenorphine groups (Supp. Table 1). The allele and phenotype frequencies were not statistically different between the two treatment groups.

Table 1.

Demographics of the methadone and buprenorphine medication groups in the genetics arm of the START trial.

| Methadone | Buprenorphine | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients (% Male) | 354 (66.4%) | 410 (70.7%) |

| European-American (%) | 295 (83.3%) | 304 (74.1%) |

| African-American (%) | 35 (9.9%) | 44 (10.7%) |

| Other Ethnicities (%) | 34 (9.6%) | 62 (15.1%) |

| Dropout Rate | 12.7% | 22.7% |

Pharmacogenetics of Dropout Rate

The metabolism statuses for six genes encoding CYP450 enzymes previously shown to metabolize opioids were analyzed with regards to dropout rate in the methadone and buprenorphine groups, as well as both groups combined. None of the analyzed genes were associated with dropout rate (Table 2). The genotypes for an additional five genes previously linked to the pharmacodynamics of opioid analgesia were also analyzed with regards to dropout rate. Genotype for 5-HTTLPR in the SLC6A4 gene was nominally associated with dropout rate when methadone and buprenorphine groups were combined (p=0.027) (Table 2). This association was not significant after correction for multiple testing.

Table 2.

Phenotypic/genotypic analysis of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic genes and dropout rates for the methadone, buprenorphine, and combined treatment groups using logistic regression.

| Methadone | Buprenorphine | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Gene | Phenotype/Genotype | N | Dropout Rate (%) | p-value | N | Dropout Rate (%) | p-value | Combined p-value |

|

| ||||||||

| Pharmacokinetic | ||||||||

| CYP1A2 | IM+EM | 159 | 13.2% | 0.848 | 187 | 20.3% | 0.294 | 0.498 |

| UM | 193 | 12.4% | 222 | 24.8% | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| CYP2B6 | PM | 26 | 23.1% | 0.231 | 35 | 17.1% | 0.439 | 0.727 |

| IM | 129 | 10.9% | 120 | 27.5% | ||||

| EM | 185 | 11.9% | 238 | 21.0% | ||||

| UM | 12 | 25.0% | 16 | 25.0% | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| CYP2C9 | PM | 14 | 14.3% | 0.682 | 12 | 41.7% | 0.176 | 0.496 |

| IM | 100 | 10.0% | 107 | 26.2% | ||||

| EM | 238 | 13.9% | 290 | 20.7% | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| CYP2C19 | PM | 10 | 20.0% | 0.867 | 8 | 37.5% | 0.717 | 0.803 |

| IM | 76 | 11.8% | 80 | 25.0% | ||||

| EM | 253 | 13.0% | 302 | 21.5% | ||||

| UM | 13 | 7.7% | 19 | 26.3% | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| CYP2D6 | PM | 52 | 15.4% | 0.798 | 54 | 27.8% | 0.276 | 0.383 |

| IM | 88 | 10.2% | 94 | 23.4% | ||||

| EM | 190 | 13.2% | 234 | 20.1% | ||||

| UM | 22 | 13.6% | 27 | 33.3% | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| CYP3A4 | PM + IM | 36 | 8.3% | 0.427 | 38 | 13.2% | 0.147 | 0.085 |

| EM | 316 | 13.3% | 371 | 23.7% | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Pharmacodynamic | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| ADRA2A (rs1800544) | C/C | 168 | 13.1% | 0.763 | 202 | 22.8% | 0.964 | 0.802 |

| C/G | 136 | 13.2% | 160 | 22.5% | ||||

| G/G | 48 | 10.4% | 47 | 23.4% | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| COMT (rs4680) | A/A | 80 | 6.3% | 0.099 | 87 | 20.7% | 0.524 | 0.091 |

| A/G | 182 | 13.7% | 194 | 21.1% | ||||

| G/G | 90 | 16.7% | 128 | 26.6% | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| HTR2A (rs6311) | A/A | 60 | 16.7% | 0.422 | 66 | 30.3% | 0.221 | 0.079 |

| A/G | 189 | 10.6% | 198 | 20.2% | ||||

| G/G | 103 | 14.6% | 145 | 22.8% | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| OPRM1 (rs1799971) | A/A | 284 | 12.3% | 0.444 | 328 | 22.6% | 0.907 | 0.601 |

| A/G+G/G | 68 | 14.7% | 81 | 23.5% | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| SLC6A4 (5-HTTLPR) | S/S | 66 | 21.2% | 0.089 | 78 | 28.2% | 0.269 | 0.027 |

| S/L | 171 | 9.9% | 189 | 19.1% | ||||

| L/L | 115 | 12.2% | 142 | 24.7% | ||||

PM = poor metabolizer; IM = intermediate metabolizer; EM = extensive metabolizer; UM = ultrarapid metabolizer; S = short allele; L = long allele

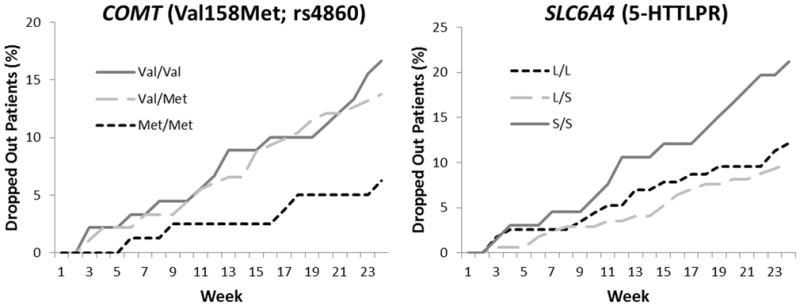

To determine the specific genotypes or phenotypes underlying the most significant p-values, pairwise analyses were performed for the phenotypes or genotypes of the four genes with nominal p-values < 0.10: CYP3A4, COMT (rs4680), SLC6A4 (5-HTTLPR), and HTR2A (rs6311) (Table 3). No significant effects were observed for CYP3A4 (EM vs IM+PM). In the combined medication group, nominally significant pairwise comparisons were observed for COMT (Val/Val (G/G) vs Met/Met (A/A), p=0.031), SLC6A4 (L/S vs S/S, p=0.0076), and HTR2A (A/A vs A/G, p=0.029). The effect in HTR2A was not present in either of the medication groups alone. In both COMT and SLC6A4, however, the effects were significant in the methadone only group (p=0.037 and p=0.029, respectively) but not the buprenorphine only group. Figure 1 presents the cumulative percentage of methadone patients who dropped out by each week of the trial based on either COMT (Figure 1a) or SLC6A4 (Figure 1b) genotype. By week 24, methadone patients with the Val/Val genotype in COMT had dropped out at a significantly higher rate (16.7%) than patients with the Met/Met genotype (6.3%, p=0.037) (Figure 1a). When the data were analyzed by SLC6A4 genotype, significantly more methadone patients with the S/S genotype left treatment (21.2%) compared to patients with the L/S genotype (9.9%, p=0.029) (Figure 1b).

Table 3.

Pairwise analyses of associations between dropout rate and phenotypes or genotypes for genes most significantly associated with dropout rate in prior analysis. PM = poor metabolizer; IM = intermediate metabolizer; EM = extensive metabolizer; S = short allele; L = long allele; OR = Odds Ratio, CI = Confidence Intervals. Higher odds ratios indicate a higher likelihood of a patient dropping out of treatment.

| Both Medications (n = 764) | Methadone (n = 354) | Buprenorphine (n = 410) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Comparison | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) |

| CYP3A4 | EM vs IM+PM | 0.085 | 1.95 (0.91 – 4.19) | 0.427 | 1.66 (0.48 – 5.77) | 0.147 | 2.06 (0.78 – 5.44) |

| COMT (rs4680) | G/G vs A/G | 0.192 | 1.32 (0.87 – 2) | 0.713 | 1.14 (0.56 – 2.34) | 0.300 | 1.32 (0.78 – 2.23) |

| G/G vs A/A | 0.031 | 1.82 (1.06 – 3.15) | 0.037 | 3.16 (1.07 – 9.31) | 0.377 | 1.34 (0.7 – 2.58) | |

| A/G vs A/A | 0.223 | 1.38 (0.82 – 2.32) | 0.051 | 2.76 (0.99 – 7.68) | 0.959 | 1.02 (0.54 – 1.9) | |

| SLC6A4 (5- HTTLPR) | L/S vs L/L | 0.168 | 0.74 (0.48 – 1.14) | 0.503 | 0.77 (0.36 – 1.65) | 0.287 | 0.75 (0.44 – 1.27) |

| L/S vs S/S | 0.008 | 0.52 (0.32 – 0.84) | 0.029 | 0.41 (0.19 – 0.91) | 0.121 | 0.61 (0.33 – 1.14) | |

| L/L vs S/S | 0.161 | 0.7 (0.43 – 1.15) | 0.143 | 0.54 (0.23 – 1.23) | 0.533 | 0.82 (0.44 – 1.53) | |

| HTR2A (rs6311) | A/A vs A/G | 0.029 | 0.57 (0.35 – 0.94) | 0.213 | 0.58 (0.25 – 1.36) | 0.083 | 0.57 (0.3 – 1.08) |

| A/G vs G/G | 0.196 | 0.76 (0.5 – 1.15) | 0.404 | 0.73 (0.35 – 1.52) | 0.608 | 0.87 (0.51 – 1.48) | |

| A/A vs G/G | 0.291 | 1.32 (0.79 – 2.23) | 0.621 | 1.26 (0.51 – 3.09) | 0.204 | 1.53 (0.79 – 2.96) | |

Figure 1.

Cumulative dropout rate for opioid dependent patients treated with methadone by genotype at either COMT (rs4680) or SLC6A4 (5-HTTLPR). Cumulative dropout for each week of the trial was defined as the percentage of patients who did not submit a urine sample on that week or at any subsequent week. Chi-square analyses were used to compare dropout at week 24 of the study by rs4680 or 5-HTTLPR genotype. A) Patients with the Val/Val genotype in COMT dropped out at a significantly higher rate by week 24 (16.7%) than patients with the Met/Met genotype (6.3%, p = 0.037). B) Significantly more patients with the S/S genotype in SLC6A4 dropped out of by week 24 treatment (21.2%) compared to patients with the L/S genotype (9.9%, p = 0.029).

Pharmacogenetics of Mean Dose

Phenotypes for all CYP450 enzymes and genotypes for all five pharmacodynamic genes were analyzed for association with mean dose of methadone and buprenorphine separately (Table 4). No significant associations were observed.

Table 4.

Phenotypic/genotypic analysis of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic genes and mean dose for the methadone and buprenorphine treatment groups using one-way ANOVA

| Methadone | Buprenorphine | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Gene | Phenotype/Genotype | N | Mean Dose ± SD (mg) | p-value | N | Mean Dose ± SD (mg) | p-value |

|

| |||||||

| Pharmacokinetic | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| CYP1A2 | IM+EM | 159 | 72.4 ± 30.2 | 0.83 | 187 | 17.0 ± 7.1 | 0.36 |

| UM | 193 | 73.2 ± 35.3 | 222 | 16.0 ± 7.1 | |||

|

| |||||||

| CYP2B6 | PM | 26 | 64.4 ± 33.8 | 0.19 | 35 | 14.7 ± 6.1 | 0.15 |

| IM | 129 | 70.7 ± 30.0 | 120 | 15.7 ± 6.8 | |||

| EM | 185 | 74.6 ± 34.8 | 238 | 17.0 ± 7.4 | |||

| UM | 12 | 86.2 ± 28.8 | 16 | 17.7 ± 6.2 | |||

|

| |||||||

| CYP2C9 | PM | 14 | 71.5 ± 23.0 | 0.90 | 12 | 15.4 ± 5.4 | 0.65 |

| IM | 100 | 74.1 ± 33.1 | 107 | 16.0 ± 7.0 | |||

| EM | 238 | 72.4 ± 33.5 | 290 | 16.7 ± 7.2 | |||

|

| |||||||

| CYP2C19 | PM | 10 | 66.4 ± 37.5 | 0.91 | 8 | 14.4 ± 5.8 | 0.42 |

| IM | 76 | 73.3 ± 33.3 | 80 | 15.5 ± 7.4 | |||

| EM | 253 | 73.1 ± 33.0 | 302 | 16.8 ± 7.0 | |||

| UM | 13 | 69.7 ± 29.3 | 19 | 15.8 ± 8.3 | |||

|

| |||||||

| CYP2D6 | PM | 52 | 77.8 ± 33.2 | 0.19 | 54 | 16.0 ± 6.3 | 0.87 |

| IM | 88 | 77.4 ± 31.3 | 94 | 16.6 ± 7.9 | |||

| EM | 190 | 69.7 ± 34.1 | 234 | 16.4 ± 7.1 | |||

| UM | 22 | 69.9 ± 27.2 | 27 | 17.3 ± 6.4 | |||

|

| |||||||

| CYP3A4 | PM + IM | 36 | 79.3 ± 39.2 | 0.22 | 38 | 16.0 ± 7.3 | 0.71 |

| EM | 316 | 72.1 ± 32.2 | 371 | 16.5 ± 7.1 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Pharmacodynamic | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| ADRA2A (rs1800544) | C/C | 168 | 73.4 ± 32.4 | 0.76 | 202 | 17.1 ± 7.3 | 0.07 |

| C/G | 136 | 73.7 ± 35.2 | 160 | 16.3 ± 7.1 | |||

| G/G | 48 | 68.2 ± 28.6 | 47 | 14.2 ± 6.3 | |||

|

| |||||||

| COMT (rs4680) | A/A | 80 | 74.4 ± 29.9 | 0.27 | 87 | 16.4 ± 7.2 | 0.82 |

| A/G | 182 | 74.5 ± 32.7 | 194 | 16.7 ± 7.0 | |||

| G/G | 90 | 67.9 ± 36.0 | 128 | 16.2 ± 7.3 | |||

|

| |||||||

| HTR2A (rs6311) | A/A | 60 | 74.7 ± 29.6 | 0.62 | 66 | 18.0 ± 7.8 | 0.12 |

| A/G | 189 | 73.7 ± 33.4 | 198 | 15.9 ± 7.2 | |||

| G/G | 103 | 70.2 ± 34.2 | 145 | 16.5 ± 6.7 | |||

|

| |||||||

| OPRM1 (rs1799971) | A/A | 284 | 72.5 ± 34.2 | 0.85 | 328 | 16.4 ± 7.4 | 0.94 |

| A/G+G/G | 68 | 74.7 ± 28.5 | 81 | 16.7 ± 4.7 | |||

|

| |||||||

| SLC6A4 (5-HTTLPR) | S/S | 66 | 71.0 ± 39.1 | 0.82 | 78 | 16.2 ± 6.7 | 0.23 |

| S/L | 171 | 72.6 ± 30.0 | 189 | 17.1 ± 7.5 | |||

| L/L | 115 | 74.2 ± 33.7 | 142 | 15.7 ± 6.8 | |||

PM = poor metabolizer; IM = intermediate metabolizer; EM = extensive metabolizer; UM = ultrarapid metabolizer; S = short allele; L = long allele

Discussion

Metabolism phenotypes in a flexible dosing scheme

Pharmacokinetic genetic variants affect the bioavailability of medications, generally by altering metabolism of the medication. In our analysis, the metabolism statuses of the CYP450 enzymes were not associated with the mean dose of either methadone or buprenorphine during the study. CYP2B6 was a likely candidate for predicting optimal methadone dose since the gene encodes the primary enzyme responsible for metabolizing methadone. However, the previous analyses of the CYP2B6 effect on methadone dose have yielded mixed results. Two older studies found no effect of CYP2B6 metabolism status on require methadone dose, while a more recent study from Levran et al found that the reduced function CYP2B6*6 allele was associated with lower doses of methadone (10, 16, 19). In the case of the START trial, poor metabolizers tended to be prescribed lower doses (mean dose ± SD: 64.4±34.4mg) than ultrarapid metabolizers (mean dose ± SD: 86.2±30.1mg), but this effect was not significant (p-value=0.19). The lack of significance is the likely result of relatively small numbers of patients in the two phenotypic groups (n=26 for poor metabolizers and n=12 for ultrarapid metabolizers), as well as large variability in mean dose across the patient population. Optimal dose may ultimately be affected by numerous environmental and genetic factors, limiting the predictive value of CYP2B6 phenotype alone.

CYP2B6 phenotype did not predict whether or not patients completed the trial. Therefore, it is not clear whether metabolism status is a relevant factor in treatment efficacy when a flexible dosing scheme is used. Patients in such a treatment plan eventually reach an appropriate dose, albeit after varying amounts of time. Further research should examine withdrawal and wellbeing in methadone patients based on CYP2B6 status. Prescription of higher starting doses of methadone and quicker dose escalation in faster metabolizers may reduce withdrawal symptoms and improve overall wellbeing in this subset of patients, even if it does not affect the dropout rate.

CYP3A4 metabolism status was also not associated with dropout rate in either the methadone or buprenorphine group, although CYP3A4 status showed a trend towards association with dropout rate when the two treatment groups were combined. This trend is notable since CYP3A4 is predicted to metabolize both medications and the effect of CYP3A4 phenotype on dropout rate was in the same direction in both treatment groups. It is possible, due to the low frequency of intermediate and poor CPY3A4 metabolizers, that CYP3A4 status might be significant and medication-independent in a larger population of opioid dependent patients.

Serotonin, dopamine, and dependence

Pharmacodynamic variants affect the downstream effects of the medication rather than altering metabolism. The most significant finding in the current study was for SLC6A4, which was associated with the dropout rate in methadone patients. SLC6A4 encodes a serotonin transporter (5-HTT; SERT) that is responsible for the uptake of serotonin from the synapse. The promoter polymorphism analyzed in this study (5-HTTLPR) has both a long (L) and short (S) allele. The short allele of the locus has previously been associated with reduced SLC6A4 mRNA expression in vitro and is linked to a number of psychiatric and neurological phenotypes, including an increased risk of opioid dependence in some studies (28, 29). Given the known effects on SLC6A4 expression, individuals with the S/S genotype would be predicted to have reduced amounts of serotonin transporter and a commensurate increase in baseline synaptic serotonin levels. A small imaging study of opioid dependent patients (n = 9) found that reduced availability of SLC6A4 protein in the brain was associated with increased time to relapse (30). Based on these findings, if patients with the S/S genotype have decreased serotonin transporters one might have expected them to be doing better than other patients in the START trial rather than worse. However, methadone patients with the S/S genotype at 5-HTTLPR in the START trial were actually less likely to complete the trial than patients with the L/S genotype.

The observed association may be related to the potential role of methadone as a serotonin-specific reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). SSRIs block the serotonin transporter, resulting in increased synaptic serotonin and elevated mood. Methadone maintenance patients have been shown to have reduced serotonin transporter availability in the midbrain compared to controls and patients with opioid dependence undergoing psychotherapy alone (31). These data agree with other evidence indicating that methadone can function as a mild SSRI (reviewed in (32)), suggesting that methadone use should lead to increases in synaptic serotonin concentrations.

Although the role of serotonin-related activity in mediating methadone efficacy is unclear, serotonin mediates feelings of well-being and SSRIs are classically used as anti-depressants. A history of depressive symptoms is associated with poor outcomes during both methadone and buprenorphine treatment for opioid dependence, and simultaneous treatment of the depression may improve efficacy of addiction treatment (5, 6, 33). Studies have shown that patients undergoing withdrawal show decreases in serotonin levels and withdrawal symptoms can be reduced by treatment with SSRIs, regardless of whether the withdrawal was caused by abstinence or administration of an opioid receptor antagonist (34, 35).

Some studies have also suggested that depressed patients with the S/S genotype at 5-HTTLPR receive less benefit from SSRIs than other patients (36, 37). If part of methadone’s effectiveness as an opioid dependence medication comes from SSRI activity, then that might explain why individuals with the S/S genotype were less likely to complete the START trial. These patients may have depressive symptoms that are not being treated by methadone due to their reduced expression of SLC6A4. Given the available evidence, the underlying mechanism connecting 5-HTTLPR genotype to methadone efficacy is still unclear. Future studies will need to assess the effect of genotype by treatment interaction on serotonin levels, as well as determine the effect of the 5-HTTLPR genotype on mood in the context of methadone treatment.

An association was also observed between the dropout rate in methadone patients and genotype at a non-synonymous variant in COMT (catechol-O-methyltransferase), a gene encoding one of the enzymes responsible for metabolizing dopamine. A common non-synonymous variant (rs4680; Val158Met) occurs in COMT and alters the activity level of the enzyme; the Met allele is associated with reduced function compared to the Val allele. This altered function has been connected to several psychiatric phenotypes. Individuals with the Met/Met genotype are more risk averse than those with the Val/Val genotype and may have better working memory and attentional control (38, 39). Met/Met individuals also showed significantly greater reward from positive experiences than Val/Val individuals, although no consistent association between the polymorphism and opioid dependence has been shown (40, 41).

Met/Met methadone patients in the START trial had a 6.25% dropout rate compared with a 17% rate for Val/Val patients. Since Met/Met individuals are predicted to have increased levels of dopamine, it is possible patients with this genotype find methadone more rewarding than other patients and are, therefore, more likely to stay in treatment. An alternate hypothesis is that the mood and personality differences associated with COMT genotype may simply make Met/Met patients more amenable to treatment in general. This latter explanation would fit with data from a recently published longitudinal study of Chinese opioid dependent patients (42). Patients who were not receiving methadone were enrolled in the study after undergoing mandatory detoxification and followed for five years. Patients carrying the Met allele were more likely than Val/Val individuals to be receiving methadone maintenance therapy and to be abstinent from heroin at the five year time point (42). Since no clear association between Val158Met genotype and susceptibility to opioid dependence has been established, these findings may indicate that the polymorphism affects the maintenance phase of opioid dependence but not necessarily initiation of the disorder.

5-HTTLPR and Val158Met genotype only had effects on dropout rate in the methadone group; however, the effect of these polymorphisms in the buprenorphine group is directionally the same as that of the methadone group. This is reflected in the pairwise comparisons in the combined treatment group (Table 3). As with CYP3A4 status, these two polymorphisms may have significant effects on buprenorphine dropout rate that were unable to be detected in the current study due to sample size. Subsequent analyses in larger populations will have to be performed to study this hypothesis.

The current study suggests that functional polymorphisms related to synaptic dopamine or serotonin levels may predict dropout rates during methadone treatment. Patients with the S/S genotype at 5-HTTLPR in SLC6A4 or the Val/Val genotype at Val158Met (rs4860) in COMT may require additional treatment, either pharmaceutical or psychiatric, to improve their chances of completing treatment for their addiction. There are some potential limitations to this study. First, none of the associations were significant following correction for multiple testing. This increases the possibility that the findings for SLC6A4 and COMT are false positives. Second, genotypes for ancestry informative markers were not available for analysis. Although the samples were predominantly from patients of European descent (78.4%), population stratification could potentially be affecting the results if there are specific differences between ethnic groups in allele frequencies and outcome measurements. Finally, START participants were randomized for the main trial and not the secondary genetics arm analyzed here. Potentially relevant factors may therefore not be truly randomized in the genetics samples, which could affect the analyses of dose and dropout. These limitations mean that replication in other methadone patient populations will be necessary to ensure the validity of these findings.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources:

Main START study funding came from the National Institute on Drug Abuse through the Clinical Trials Network (CTN) through a series of grants provided to each participating node: the Pacific Northwest Node (U10 DA01714), the Oregon Hawaii Node (U10 DA013036), the California/Arizona Node (U10 DA015815), the New England Node (U10 DA13038), the Delaware Valley Node (U10 DA13043), the Pacific Region Node (U10 DA13045), and the New York Node (U10 DA013046). R.C.C was supported by NIDA grant K01 DA036751. W.H.B was supported by the Delaware Valley Node (U10 DA13043) and by R21 DA036808.

We thank Sandra Gunselman and Nina King for their help with genotyping and Michael Jablonski for his help on collaborations.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

Genotyping on Assurex Health GeneSight® Analgesic, Psychotropic and ADHD panels was performed by Assurex Health Inc. as an in-kind donation. J.L., A.G., and B.M.D. are employees and shareholders of Assurex Health Inc. The authors declare no other conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2:CD002207. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crist RC, Clarke TK, Ang A, Ambrose-Lanci LM, Lohoff FW, Saxon AJ, et al. An intronic variant in OPRD1 predicts treatment outcome for opioid dependence in African-Americans. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013 Sep;38(10):2003–10. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brewer DD, Catalano RF, Haggerty K, Gainey RR, Fleming CB. A meta-analysis of predictors of continued drug use during and after treatment for opiate addiction. Addiction. 1998 Jan;93(1):73–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clarke TK, Crist RC, Ang A, Ambrose-Lanci LM, Lohoff FW, Saxon AJ, et al. Genetic variation in OPRD1 and the response to treatment for opioid dependence with buprenorphine in European-American females. Pharmacogenomics J. 2014 Jun;14(3):303–8. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2013.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Senbanjo R, Wolff K, Marshall EJ, Strang J. Persistence of heroin use despite methadone treatment: poor coping self-efficacy predicts continued heroin use. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2009 Nov;28(6):608–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nunes EV, Levin FR. Treatment of depression in patients with alcohol or other drug dependence: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004 Apr 21;291(15):1887–96. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.15.1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iribarne C, Picart D, Dreano Y, Bail JP, Berthou F. Involvement of cytochrome P450 3A4 in N-dealkylation of buprenorphine in human liver microsomes. Life Sci. 1997;60(22):1953–64. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moody DE, Slawson MH, Strain EC, Laycock JD, Spanbauer AC, Foltz RL. A liquid chromatographic-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometric method for determination of buprenorphine, its metabolite, norbuprenorphine, and a coformulant, naloxone, that is suitable for in vivo and in vitro metabolism studies. Anal Biochem. 2002 Jul 1;306(1):31–9. doi: 10.1006/abio.2002.5673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Picard N, Cresteil T, Djebli N, Marquet P. In vitro metabolism study of buprenorphine: evidence for new metabolic pathways. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005 May;33(5):689–95. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.003681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crettol S, Deglon JJ, Besson J, Croquette-Krokar M, Hammig R, Gothuey I, et al. ABCB1 and cytochrome P450 genotypes and phenotypes: influence on methadone plasma levels and response to treatment. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006 Dec;80(6):668–81. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kharasch ED, Stubbert K. Role of cytochrome P4502B6 in methadone metabolism and clearance. J Clin Pharmacol. 2013 Mar;53(3):305–13. doi: 10.1002/jcph.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Totah RA, Sheffels P, Roberts T, Whittington D, Thummel K, Kharasch ED. Role of CYP2B6 in stereoselective human methadone metabolism. Anesthesiology. 2008 Mar;108(3):363–74. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181642938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerber JG, Rhodes RJ, Gal J. Stereoselective metabolism of methadone N-demethylation by cytochrome P4502B6 and 2C19. Chirality. 2004 Jan;16(1):36–44. doi: 10.1002/chir.10303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee HY, Li JH, Sheu YL, Tang HP, Chang WC, Tang TC, et al. Moving toward personalized medicine in the methadone maintenance treatment program: a pilot study on the evaluation of treatment responses in Taiwan. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:741403. doi: 10.1155/2013/741403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kharasch ED, Regina KJ, Blood J, Friedel C. Methadone Pharmacogenetics: CYP2B6 Polymorphisms Determine Plasma Concentrations, Clearance, and Metabolism. Anesthesiology. 2015 Nov;123(5):1142–53. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levran O, Peles E, Hamon S, Randesi M, Adelson M, Kreek MJ. CYP2B6 SNPs are associated with methadone dose required for effective treatment of opioid addiction. Addict Biol. 2013 Jul;18(4):709–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2011.00349.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsai HJ, Wang SC, Liu SW, Ho IK, Chang YS, Tsai YT, et al. Assessment of CYP450 genetic variability effect on methadone dose and tolerance. Pharmacogenomics. 2014 May;15(7):977–86. doi: 10.2217/pgs.14.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang SC, Ho IK, Tsou HH, Liu SW, Hsiao CF, Chen CH, et al. Functional genetic polymorphisms in CYP2C19 gene in relation to cardiac side effects and treatment dose in a methadone maintenance cohort. OMICS. 2013 Oct;17(10):519–26. doi: 10.1089/omi.2012.0068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crettol S, Deglon JJ, Besson J, Croquette-Krokkar M, Gothuey I, Hammig R, et al. Methadone enantiomer plasma levels, CYP2B6, CYP2C19, and CYP2C9 genotypes, and response to treatment. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005 Dec;78(6):593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen CH, Wang SC, Tsou HH, Ho IK, Tian JN, Yu CJ, et al. Genetic polymorphisms in CYP3A4 are associated with withdrawal symptoms and adverse reactions in methadone maintenance patients. Pharmacogenomics. 2011 Oct;12(10):1397–406. doi: 10.2217/pgs.11.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oneda B, Crettol S, Bochud M, Besson J, Croquette-Krokar M, Hammig R, et al. beta-Arrestin2 influences the response to methadone in opioid-dependent patients. Pharmacogenomics J. 2011 Aug;11(4):258–66. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2010.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gainetdinov RR, Premont RT, Bohn LM, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG. Desensitization of G protein-coupled receptors and neuronal functions. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:107–44. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujita W, Gomes I, Devi LA. Mu-Delta opioid receptor heteromers: New pharmacology and novel therapeutic possibilities. Br J Pharmacol. 2014 Feb 26; doi: 10.1111/bph.12663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crettol S, Besson J, Croquette-Krokar M, Hammig R, Gothuey I, Monnat M, et al. Association of dopamine and opioid receptor genetic polymorphisms with response to methadone maintenance treatment. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008 Oct 1;32(7):1722–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kolpe M, Carlson GA. Influence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms on methadone treatment outcome. Am J Addict. 2007 Jan-Feb;16(1):46–8. doi: 10.1080/10601330601080073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saxon AJ, Ling W, Hillhouse M, Thomas C, Hasson A, Ang A, et al. Buprenorphine/Naloxone and methadone effects on laboratory indices of liver health: a randomized trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013 Feb 01;128(1–2):71–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hser YI, Saxon AJ, Huang D, Hasson A, Thomas C, Hillhouse M, et al. Treatment retention among patients randomized to buprenorphine/naloxone compared to methadone in a multi-site trial. Addiction. 2014 Jan;109(1):79–87. doi: 10.1111/add.12333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cao J, Hudziak JJ, Li D. Multi-cultural association of the serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4) with substance use disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013 Aug;38(9):1737–47. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muller CP, Homberg JR. The role of serotonin in drug use and addiction. Behavioural brain research. 2015 Jan 15;277:146–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin SH, Chen KC, Lee SY, Yao WJ, Chiu NT, Lee IH, et al. The association between availability of serotonin transporters and time to relapse in heroin users: a two-isotope SPECT small sample pilot study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012 Sep;22(9):647–50. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yeh TL, Chen KC, Lin SH, Lee IH, Chen PS, Yao WJ, et al. Availability of dopamine and serotonin transporters in opioid-dependent users--a two-isotope SPECT study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012 Mar;220(1):55–64. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2454-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gillman PK. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors, opioid analgesics and serotonin toxicity. Br J Anaesth. 2005 Oct;95(4):434–41. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dreifuss JA, Griffin ML, Frost K, Fitzmaurice GM, Potter JS, Fiellin DA, et al. Patient characteristics associated with buprenorphine/naloxone treatment outcome for prescription opioid dependence: Results from a multisite study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013 Jul 1;131(1–2):112–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gray AM. The effect of fluvoxamine and sertraline on the opioid withdrawal syndrome: a combined in vivo cerebral microdialysis and behavioural study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002 Jun;12(3):245–54. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(02)00028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harris GC, Aston-Jones G. Augmented accumbal serotonin levels decrease the preference for a morphine associated environment during withdrawal. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001 Jan;24(1):75–85. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00184-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smeraldi E, Zanardi R, Benedetti F, Di Bella D, Perez J, Catalano M. Polymorphism within the promoter of the serotonin transporter gene and antidepressant efficacy of fluvoxamine. Mol Psychiatry. 1998 Nov;3(6):508–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Serretti A, Kato M, De Ronchi D, Kinoshita T. Meta-analysis of serotonin transporter gene promoter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) association with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor efficacy in depressed patients. Mol Psychiatry. 2007 Mar;12(3):247–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Farrell SM, Tunbridge EM, Braeutigam S, Harrison PJ. COMT Val(158)Met genotype determines the direction of cognitive effects produced by catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibition. Biol Psychiatry. 2012 Mar 15;71(6):538–44. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blasi G, Mattay VS, Bertolino A, Elvevag B, Callicott JH, Das S, et al. Effect of catechol-O-methyltransferase val158met genotype on attentional control. J Neurosci. 2005 May 18;25(20):5038–45. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0476-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wichers M, Aguilera M, Kenis G, Krabbendam L, Myin-Germeys I, Jacobs N, et al. The catechol-O-methyl transferase Val158Met polymorphism and experience of reward in the flow of daily life. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008 Dec;33(13):3030–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gatt JM, Burton KL, Williams LM, Schofield PR. Specific and common genes implicated across major mental disorders: a review of meta-analysis studies. J Psychiatr Res. 2015 Jan;60:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Su H, Li Z, Du J, Jiang H, Chen Z, Sun H, et al. Predictors of heroin relapse: Personality traits, impulsivity, COMT gene Val158met polymorphism in a 5-year prospective study in Shanghai, China. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2015 Dec;168(8):712–9. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]