Abstract

Numerous attempts to produce anti-viral vaccines by harnessing memory CD8-T cells have failed. A barrier to progress is that we do not know what makes an antigen a viable target of protective CD8 T-cell memory. We found that in mice susceptible to lethal mousepox (the mouse homolog of human smallpox), a dendritic cell vaccine that induced memory CD8 T-cells fully protected mice when the infecting virus produced antigen in large quantities and with rapid kinetics. Protection did not occur when the antigen was produced in low amounts, even with rapid kinetics, and protection was only partial when the antigen was produced in large quantities but with slow kinetics. Hence, the amount and timing of antigen expression appear to be key determinants of memory CD8 T-cell anti-viral protective immunity. These findings may have important implications for vaccine design.

Introduction

CD8 T-cells scan the surface of professional antigen presenting cells (pAPC) in secondary lymphoid organs in search of an antigenic peptide bound to major histocompatibility class I (MHC I) molecules. In all cells, MHC I molecules bind peptides derived from the normal degradation of the cellular proteome and display them at the cell surface (1). These self-peptides normally do not induce a CD8 T-cell response. However, when cells become infected by a virus, some of the peptides presented by MHC I derive from the degradation of viral proteins. When the cells presenting viral peptides are pAPC, specific CD8-T cells become activated, increase their numbers, distribute throughout the body, and kill any cell that presents their cognate peptide on MHC I. After the infection subsides, an expanded pool of virus-specific CD8 T-cells remains. These cells, known as memory CD8 T-cells, can potentially protect from subsequent infections by viruses carrying the cognate peptide (2). Thus, memory CD8 T-cells induced by vaccines can theoretically protect from virulent viruses. Yet, while CD8 T-cell vaccines have been effective in some experimental setups, they have failed to fulfill their promise (3, 4). A reason for this failure might be that we do not know what makes an antigen an effective target of protective memory CD8 T-cells.

Orthopoxviruses (OPV) are a genus of DNA viruses that include the agent of human smallpox variola virus (VARV), vaccinia virus (VACV), that was used as the vaccine that eradicated smallpox, and ectromelia virus (ECTV), a pathogen of the laboratory mouse. Following footpad infection, ECTV’s rapidly disseminates through the lympho-hematogenous route, causing a lethal disease known as mousepox in susceptible but not in resistant strains of mice. The main target organs of ECTV are the liver and the spleen where it causes massive necrosis in mousepox-susceptible but not in mousepox resistant strains. Indeed, death in susceptible strains is thought to be due to the liver necrosis.

As with many other viruses, the anti-OPV CD8 T-cell responses are directed to multiple peptides; the one eliciting the strongest CD8 T-cell response is called immunodominant and those that induce lower responses are called subdominant. The immunodominant peptide of ECTV and also VACV is TSYKFESV (amino acid single letter code) (5). It is derived from the degradation of the high-abundance protein B8, an IFN-γ decoy receptor encoded by the early/late genes B8R in VACV and EVM158 in ECTV (6). TSYKFESV binds with high affinity to the mouse MHC I molecule Kb which is present in both, mousepox resistant C57BL/6 (B6) and mousepox-susceptible B6.D2-(D6Mit149-D6Mit15)/LusJ (B6.D2-D6) mice, a B6 congenic recombinant inbred strain.

After footpad infection with ECTV, B6 mice show few signs of disease, and mount strong anti-viral CD8 T-cell responses to multiple peptides, but dominated by anti-TSYKFESV cells (5, 7). Conversely, male B6.D2-D6 die of mousepox with almost absent CD8 T-cell responses and extreme lymphopenia in secondary lymphoid organs (7, 8). Yet, the inadequate B6.D2-D6 responses to ECTV are not due to an intrinsic defect in CD8 T-cell immunity because they mount very strong CD8 T-cell responses to VACV, including to TSYKFESV. Notably, B6.D2-D6 mice can be protected from mousepox by memory CD8 T-cells specific for TSYKFESV and to some but not all subdominant peptides (7). Thus, not all immunogenic peptides are obligate targets of protective memory CD8 T-cells suggesting a possible reason for the failure of many CD8 T-cell vaccines.

Materials and Methods

Viruses

Stocks were produced and titers determined as previously (9). ECTV recombinants were generated as previously (10). The scheme for the construction of the viruses in this paper is depicted in Figure S1A.

RT-qPCR (RNA transcription followed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction)

L929 cells (ATCC) in 24 well plates were infected with 1 plaque-forming unit/cell and RNA was extracted at the indicated times. When indicated, AraC (Sigma-Aldrich) was added at a concentration of 40 μg/ml. qPCR was performed as previously (11).

Western Blot

We used standard procedures. Rabbit polyclonal anti-B8 (12) was from Dr. R. Mark Buller (Saint Louis University, Mo). Rabbit polyclonal anti-EVM166 has been described (13). Anti-beta actin antibody was from Abcam.

Mice, vaccination and infection

B6 mice were from Taconic and B6.SJL (CD45.1) mice were from NCI. B6.D2-D6 mice were bred at FCCC. Vaccination with dendritic cells (DC) pulsed with TSYKFESV (DC-TSYFESV) was as before. This results in ~4% of the CD8 T-cells specific for TSYKFESV one month after boosting (7). Unless indicated, mice were infected with ECTV in the left footpad with 30 μl PBS containing 3×103 pfu and monitored as before (14). These studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of FCCC.

Histopathology

Was as previously (13).

Flow cytometry

Was as previously (14). Abs to CD4, CD8a, CD45.2 and CD69 were from Biolegend. Anti-human/mouse Granzyme B (GzmB) was from Caltag. H-2Kb:Ig recombinant fusion protein (Dimer-X, BD) incubated with synthetic peptides was used as recommended by the manufacturer.

Data display and statistical analysis

Unless indicated, data correspond to one representative experiment of at least two similar experiments with groups of three to six mice. Statistical analysis was performed using Graph Pad Prism software. One-way ANOVA, unpaired two-tailed t, Mann-Whitney or Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) tests were used as applicable.

Results

We made ECTV lacking EVM158 but producing VACV B8 (from an introduced VACV B8R gene) driven by the promoters of the VACV genes B8R, C3L, and D2L (hereafter, ECTV pB8R, pC3L and pD2L, respectively). Because these viruses carried the E. coli gene gpt for selection, we also made an EVM158-null virus that carried gpt but not B8R (herein ECTV gpt) (Figure S1). We made the viruses producing VACV B8 and not ECTV B8 because VACV B8 fully conserves TSYKFESV, but does not bind mouse IFN-γ (6). We chose the promoters of B8R, C3L, and D2L given their expected levels of expression according to Assarsson et al. (15).

During OPV infection, early genes are expressed before and late genes are expressed after DNA replication (16). In cells infected with ECTV pB8R and pD2L, expression of B8R was detectable by RT-qPCR at 2 h post-infection (hpi) and continuously increased up to 24 hpi (the last time point tested) suggesting B8R is an early/late gene in ECTV pB8R and pD2L. Yet, expression was always higher in cells infected with ECTV pB8R than with pD2L. In cells infected with ECTV pC3L, B8R expression was not detectable at 2 hpi, was low at 3 hpi, and steadily increased up to 24 hpi (Figure S1C) suggesting B8R is a late gene in ECTV pC3L. Infection for 8 h in the presence of cytosine arabinoside (araC), which prevents the expression of late but not early viral genes (17), significantly decreased the expression of B8R in cells infected with ECTV pC3L but not with ECTV pB8R or ECTV pD2L (Figure S1D) further suggesting that B8R is early/late in ECTV pB8R and pD2L, and late in ECTV pC3L. Western blot (WB) at 6 hpi showed that cells infected with ECTV pB8R produced more B8 than cells infected with ECTV pD2L and cells infected with ECTV pC3L did not produce B8 (Figure 1A). Control WB for actin and the viral protein EVM166 demonstrated similar loading and infection efficiency, respectively. Serial dilution indicated that the difference in B8 content between cells infected with pB8R and pD2L was ~3-fold (Figure 1B). WB at 24 hpi showed that cells infected with ECTV pB8R and p3CL produced high amounts of B8 while cells infected with p2DL produced less (Figure 1C). Serial dilution showed that cells infected with ECTV p3CL and pB8R contained similar amounts of B8 (Figure 1D) while those infected with pD2L contained ~30-fold less (Figure 1E). Thus, ECTV pB8R produces relatively high and ECTV pD2L produces low amounts of B8 protein during early and late infection (early/late high and early/late low, respectively), and ECTV pC3L produces high amounts of B8 protein but only late (late/high). Importantly, all the viruses remained similarly fully virulent because 3,000 plaque forming units (pfu) killed B6.D2-D6 mice with indistinguishable kinetics. Control mousepox-resistant B6 mice infected with ECTV gpt survived the infection (Figure 1E).

Figure 1. Generation and characterization of ECTV producing variable amounts of B8 protein.

A) B-SC-1 cells were infected with 5 PFUs of the indicated viruses. At 6 hpi, the cells were lysed and analyzed by WB. The same membrane was probed with Abs to B8, EVM166 or β-actin as indicated. B) The lysates of ECTV pB8R infected cells at 6 hpi were diluted as indicated and compared to those from undiluted pD2L infected cells. C) As in A but with lysates from 24 h infected cells. D) The lysates of ECTV pB8R and pC3L infected cells at 24 hpi were diluted in parallel. E) The lysates of ECTV pB8R infected cells at 24 hpi were diluted as indicated and compared to those from undiluted pD2L infected cells. F) B6.D2-D6 and B6 mice were infected with the indicated viruses and survival was monitored. Data are representative of two similar experiments.

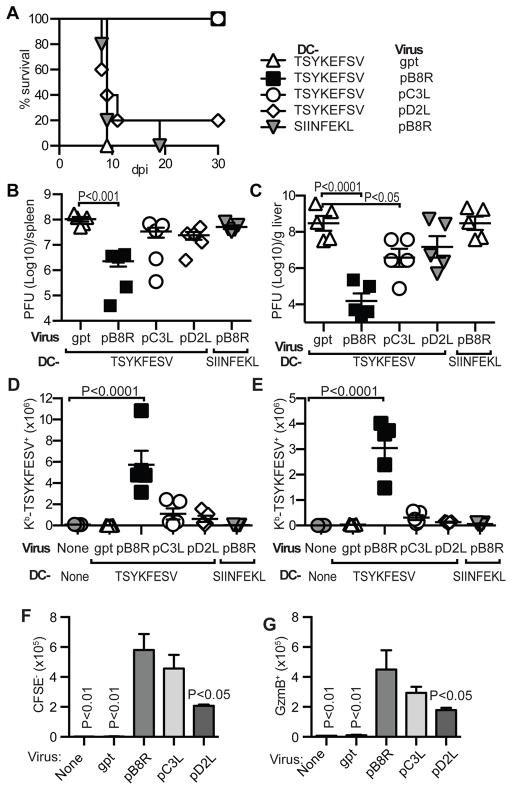

We have shown that memory CD8 T-cells induced by vaccination with DC-TSYKFESV protect B6.D2-D6 mice from death and pathology caused by wild type (WT) ECTV (7). Hence, we vaccinated B6.D2-D6 mice with DC-TSYKFESV or DC-SIINFEKL as control. As before (7) this resulted in ~4% TSYKFESV+ CD8+ T cells (data not shown). Next, we challenged the vaccinated mice with the different viruses to determine survival, virus loads, histopathology, and memory CD8 T-cell responses (experimental scheme in Figure S2A). DC-TSYKFESV vaccinated mice were fully and significantly protected from death caused by ECTV pB8R (early/late high) or ECTV pC3L (late high) but not from ECTV pD2L (early/late low) or control ECTV gpt. Control mice immunized with DC-SIINFEKL succumbed to ECTV pB8R (Figure 2A). Thus, DC-TSYKFESV vaccination fully protect from lethality when B8 is produced in high amounts whether early/late (ECTV pB8R) or only late (ECTV pC3L) but do not protect when B8 is produced early/late but in low amounts (ECTV pD2L). This was not due to diverging virulence of the viruses because pB8R (full protection) and pD2L (no protection) were both fully lethal not only at 3000 pfu (Figure 1E) but also at 300 pfu and partially lethal at 30 pfu (data not shown).

Figure 2. Only ECTV expressing high amounts of early antigen is effectively controlled by anti-TSYKFESV memory cells in mousepox susceptible B6.D2-D6 mice.

A–E) B6.D2-D6 mice were immunized with DC-TSYFESV or DC-SIINFEKL and challenged with different viruses (see experimental scheme in Figure S2A). A) Survival of mice immunized/challenged as indicated. DC-TSYKFESV/pB8R and DC-TSYKFESV/p3CL vs. DC-TSYKFESV/pD2L P=0.012. DC-TSYKFESV/pB8R and DC-TSYKFESV pC3L vs. DC-TSYKFESV/gpt and DC-SIINFEKL/pB8R P=0.002. All other comparisons were not significant. B) Virus titers at 7 dpi in the spleens of mice immunized and challenged as indicated (n=5/group, the experiment was repeated twice, only statistically significant differences are shown). C) As in C but in the liver (representative viral immunohistochemistry of livers are shown in Figure S2B). D–E) Absolute number of Kb-TSYKFESV+ CD8 T-cells in the spleens (D) and livers (E) of mice immunized and infected as indicated (n=5/group, the experiment was repeated twice, only statistically significant differences are shown, representative flow cytometry plots used for the calculations are shown in Figure S2C). F–G) Splenocytes from DC-TSIKFESV immunized B6 mice were labeled with CFSE and adoptively transferred into B6.CD45.1. The mice were infected with the indicated viruses and at 7 dpi the response of the transferred cells was analyzed (see experimental scheme in Figure S2D and gating strategy in Figure S2E). F) Number of Kb-TSYKFESV+ CD45.2+ CFSE− cells/spleen. G) Number Kb-TSYKFESV+ CD45.2+ GzmB+ cells/spleen. Data are representative of two similar experiments with 2–4 mice/group. P values are compared to pB8R.

While protection from death is essential, vaccines should also protect from pathology. Notably, mice immunized with DC-TSYKFESV controlled the replication ECTV pB8R (early/late high) in the spleen (Figure 2B) and liver (Figure 2C) significantly better than the replication of all the other viruses, including ECTV pC3L (late high). Consistently, the livers of mice infected with ECTV pB8R had much less staining with an antibody to the viral protein EVM135 than the livers of mice infected with the other viruses (Figure S2B). Thus, DC-TSYKFESV immunization protected from lethal mousepox caused by ECTV pB8R (early/late high) and pC3L (late high), but only those infected with ECTV pB8R were protected from high virus loads and organ pathology. These findings indicated that the timing of antigen expression is critical for protection against pathology and disease.

Next, we analyzed the memory CD8 T-cell recall responses of DC-TSYKFESV-immunized B6.D2-D6 mice at 7 days after challenge with the different viruses. Only the mice infected with ECTV pB8R had significantly more TSYKFESV-specific CD8 T-cells in their livers and spleens than mice challenged with ECTV gpt (Figure 2D and E and Figure S2C). The ability of ECTV pB8R to induce a strong memory CD8 T-cell responses in susceptible mice was likely associated with increase antigen presentation, because when we adoptively transferred CFSE labeled splenocytes from DC-TSYKFESV immunized B6 mice into B6-CD45.1 mice (experimental scheme in Figure S2D), donor anti-TSYKFESV memory CD8 T-cells proliferated and expanded to a significantly larger extent in mice challenged with ECTV pB8R than in mice challenged with ECTV pD2L (Figure 2F and S2E) and also more of them produced GzmB (Figure 2G and S2E). Thus, only a virus that rapidly produced high amounts of B8 significantly recalled and expanded the anti-TSYKFESV memory CD8 T-cells in mousepox-susceptible B6.D2-D6 mice and induced better proliferation and effector differentiation in mousepox-resistant B6-CD45.1 mice.

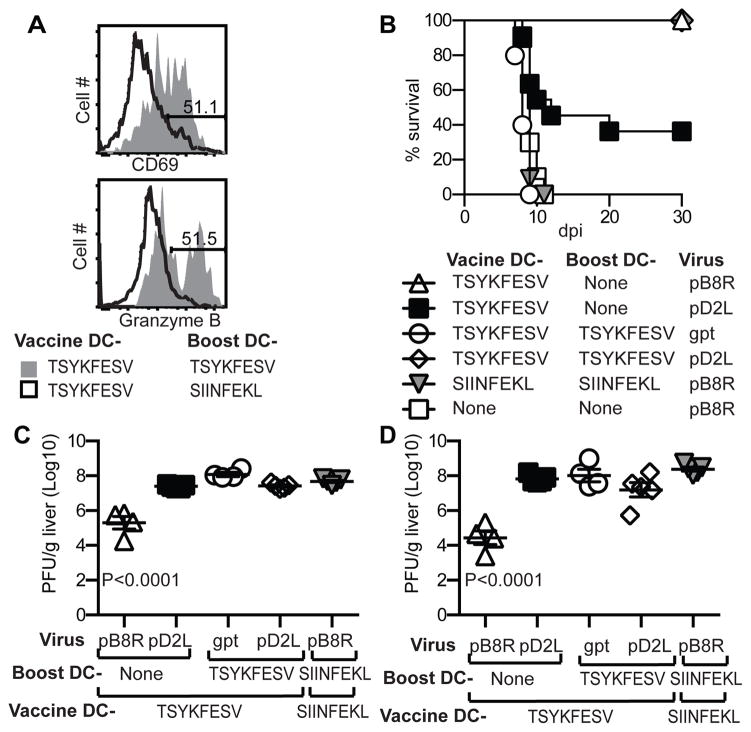

We next asked whether reactivating the memory CD8 T-cells could improve protection from ECTV pD2L. We vaccinated B6.D2-D6 mice with DC-TSYKFESV or DC-SIINFEKL (as control) as in the experiments above, but some mice were boosted three days before analysis and/or virus challenge with DC-TSYKFESV or DC-SIINFEKL (experimental scheme in Figure S2F). Boosting with DC-TSYKFESV but not with DC-SIINFEKL resulted in the expression of granzyme B (GzmB) and CD69 in anti-TSYKFESV CD8 T-cells indicating that they had become effectors (Figure 3A). Mice vaccinated and boosted with DC-TSYKFESV survived infection with ECTV pD2L (Figure 3B). However, the protection induced by boosting was incomplete, because similarly treated mice had high virus loads in liver (Figure 3C) and spleen (Figure 3D) 7 days after challenge, had a significant reduction in the cellularity of their spleens, which is a typical sign of mousepox (Figure S2G), and had wide dispersal of the virus in their livers as determined by immuno-histochemistry (Figure S2H). Thus, while effector CD8 T-cells can improve survival, they do not protect from disease when the virus produces the antigen in low quantities.

Figure 3. Pre-activating anti-TSYKFESV memory CD8 T-cells increases survival but does not protect B6-D2-D6 mice from pathology following low-antigen producing ECTV infection.

Mousepox susceptible B6.D2-D6 mice were immunized (2X) with DC-TSYKFESV or DC-SIINFEKL. One month later, the memory cells were re-activated with DC-TSYFESV or DC-SIINFEKL and three days later the splenocytes were collected for analysis or the mice infected as indicated (see experimental scheme in Figure S2F). A) Flow cytometry showing CD69 and granzyme B expression in TSYKFESV+ CD8+ splenocytes from mice immunized with DC-TSYKFESV and reactivated as indicated. B) Survival of the indicated mice. Data correspond to two pooled experiments with 5 mice/group in each (total displayed is 10 mice/group. P=0.0018 for DC-TSYKFESV Memory/pD2L vs. DC-TSYKFESV Effectors/pD2L). C) Virus titers at 7 dpi in the spleens of mice immunized and challenged as indicated (n=5/group, the experiment was repeated twice, only statistically significant differences are shown, spleen cell counts are shown in Figure S2G). D) As in C but in the liver (representative viral immunohistochemistry of livers is shown in Figure S2H).

It was possible that anti-TSYKFESV memory CD8 T-cells failed to protect from a virus producing low B8 because the amount of B8 was insufficient for the display of Kb-TSYKFESV complexes at the surface of infected cells in vivo. Alternatively, Kb-TSYKFESV complexes could be displayed but at densities that were insufficient to recall a protective memory CD8 T-cell response in susceptible mice. Thus, we next tested whether the different viruses could elicit anti-TSYKFESV CD8 T-cell responses in mousepox resistant B6 mice. We found that B6 mice infected with ECTV pB8R, pC3L or pD2L but not ECTV gpt had significantly more TSYKEFSV-specific cells than uninfected mice at 7 dpi. However, the anti-TSYKFESV responses were highest in mice infected with ECTV pB8R (early/late high), intermediate in mice infected with ECTV pC3L (late high), and lowest in mice infected with ECTV pD2L (early/late low) (Figure 4A and B), while the overall anti-ECTV CD8 T cell responses (the sum of all the specificities), as determined by gzmB staining of total CD8 T cells, were similar for all the viruses (Figure 4A and C). While these results confirm that the the amount of antigen affects the magnitude of the primary CD8 T-cell response (18), when compared to other known ECTV epitopes (5, 7), the anti-TSYKFESV response was immunodominant in mice infected with ECTV pB8R, and codominant with ECTV pC3L or pD2L (Figure 4D). Thus, in vivo, Kb-TSYFESV is displayed at the surface of cells in sufficient amounts to elicit dominant or co-dominant CD8 T-cell response for all viruses in mousepox resistant mice.

Figure 4. ECTV pB8R, pC3L, and pD2L efficiently induce anti-TSYKFESV CD8 T-cell responses in mousepox resistant B6 mice.

B6 mice were infected with the indicated viruses and at 7 dpi the CD8 T cell responses were analyzed and compared to uninfected controls. A) Representative flow cytometry plots gated on CD8 T-cells. The frequencies of cells in each quadrant are indicated. B) Absolute number of CD8 that stained with Kb-TSYKFESV dimers. Data correspond to the mean ± SEM of three mice/group and are representative of two similar experiments. P<0.0001 uninfected vs. pB8R or pC3L, P<0.05 for pB8R vs. pC3L, P<0.0001 for pB8R vs. pD2L, P<0.01 for pC3L vs. pD2L. C) Absolute number of GzmB+ cells among total CD8 T-cells in mice challenged with the indicated viruses. Data correspond to mean ± SEM of three mice/group and representative of two similar experiments. P<0.0001 for uninfected vs all others. All other comparisons were non-significant. D) The magnitude of the CD8 T-cell responses to various epitopes were determined using Kb-dimers loaded with the indicated peptides. Viruses as indicated at the top of each graph. Data correspond to two pooled experiments with three mice/group each and is displayed as mean ± SEM. For uninfected, all comparisons were non-significant. For WT, P<0.0001 for TSYKFESV vs. all others except SIFRLNI (P<0.05); all other comparisons were non-significant. For gpt, all comparisons were non-significant. For pB8R P<0.0001 for TSYKFESV vs. all others except SIFRLNI (P<0.001); other comparisons were not significant. For pC3L, P<0.01 for TSYKFESV vs. all others except SIFRFLNI (ns); all other comparisons were non-significant. For pD2L, P<0.01 for TSYKFESV vs. STNFNNL, P<0.05 for TSYKFESV vs. SIFRFLNI. All other comparisons were non-significant.

Discussion

We show that memory CD8 T-cells are efficiently recalled and fully protect a susceptible host from disease and/or death only when their cognate antigen is produced in relatively large quantities and with rapid kinetics. Notably, ECTV pC3L (late high) and pD2L (early/late low) were not good targets of protective anti-TSYKFESV memory CD8 T-cells despite that the amounts of B8 they produced resulted in presentation of Kb-TSYKFESV complexes sufficient to elicit co-dominant anti-viral CD8 T-cell response in resistant mice. Hence, epitopes that induce potent primary CD8 T-cell responses may not induce protective recall responses, and the amount of antigen produced by the virus might be more important for the recall of memory CD8 T-cells in susceptible hosts than for the elicitation of a primary response in resistant hosts. Pre-activating the memory cells before challenge with pD2L (early/late low) significantly improved survival but did not prevent pathology, suggesting that low-expressed antigens are also inadequate targets for secondary effector CD8 T-cells. In addition, our data also demonstrate that the amount of antigen produced by a virus affects the strength but is not critical for the induction of a strong primary CD8 T-cell response in genetically resistant hosts.

Our work seems to contradict the dogmatic view that the amount of peptide-MHC at the surface of target cells may not be important for memory CD8 T-cell protection. This idea likely arose from the finding that in vitro, one or a few peptide-MHC complexes are sufficient for CD8-T cell-mediated killing (19). While for technical reasons we were unable to directly quantify Kb-TSYKFESV complexes or processed TSYKFESV, from the B8 expression data and the experiments with adoptively transferred memory cells, we propose that in vivo, a relatively high density of peptide-MHC at the surface of infected cells is necessary for full anti-viral protection by secondary effectors. A possible reason for our finding may be that protection requires not only cytotoxicity but also rapid CD8 T-cell expansion, which requires high levels of peptide-MHC at the surface of antigen-presenting cells (20). This is supported by our adoptive transfer experiments.

Our results show that insufficient quantity of antigen produced by the pathogen may explain why many naturally immunogenic peptides fail to recall protective memory CD8 T-cell responses. This finding contrasts with the prevalent view that the obstacle for the production of protective CD8 T-cell vaccines is in the induction of a sufficient number of high quality memory cells (21, 22). We have previously shown that TSYKFESV-specific memory CD8 T-cells deficient in IFN-γ (which by definition are “poor quality”) fully protect B6.D2-D6 mice from ECTV WT lethality and pathology (23). Thus, for protective immunity, antigen amount might be more important than memory CD8 T-cell quality. In summary, our results suggest that the vaccines more likely to succeed are those that induce memory CD8 T-cells directed to antigens produced in large amounts and possibly at early stages of the virus life cycle and are likely to fail when the antigenic protein is produced in low amounts. Our results are in principle applicable to a poxvirus and likely useful to develop novel vaccines to large DNA viruses. Whether it also applies to smaller RNA viruses, needs to be tested, but, it may be complicated to do because of the difficulty at unlinking genetic manipulation and virulence in this type of viruses. It would also be of interest to determine if this also applies to cancer vaccines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Fox Chase Cancer Center Laboratory Animal, Biostatistics, Flow Cytometry, Histopathology, and Tissue Culture Facilities, Thomas Jefferson University laboratory animal facility, Ms. Felicia Roscoe for technical work, Dr. Andres Klein-Szanto for histopathology, and Dr. Samuel Litwin for statistical analyses.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants R01AI065544 and R01AI110457 to L.J.S. S.R. was partly supported by NIH grant No. 2T32 CA-009037 to FCCC. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

References

- 1.York IA, Rock KL. Antigen processing and presentation by the class I major histocompatibility complex. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:369–396. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Welsh RM, Selin LK, Szomolanyi-Tsuda E. Immunological memory to viral infections. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:711–743. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banchereau J, Palucka AK. Dendritic cells as therapeutic vaccines against cancer. Nature reviews Immunology. 2005;5:296–306. doi: 10.1038/nri1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palucka K, Banchereau J. Dendritic-cell-based therapeutic cancer vaccines. Immunity. 2013;39:38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tscharke DC, Karupiah G, Zhou J, Palmore T, Irvine KR, Haeryfar SM, Williams S, Sidney J, Sette A, Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. Identification of poxvirus CD8+ T cell determinants to enable rational design and characterization of smallpox vaccines. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2005;201:95–104. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alcami A, Smith GL. Vaccinia, cowpox, and camelpox viruses encode soluble gamma interferon receptors with novel broad species specificity. Journal of virology. 1995;69:4633–4639. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4633-4639.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Remakus S, Rubio D, Ma X, Sette A, Sigal LJ. Memory CD8+ T cells specific for a single immunodominant or subdominant determinant induced by peptide-dendritic cell immunization protect from an acute lethal viral disease. Journal of virology. 2012;86:9748–9759. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00981-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang M, Orr MT, Spee P, Egebjerg T, Lanier LL, Sigal LJ. CD94 Is Essential for NK Cell-Mediated Resistance to a Lethal Viral Disease. Immunity. 2011;34:579–589. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang M, Sigal LJ. Direct CD28 costimulation is required for CD8+ T cell-mediated resistance to an acute viral disease in a natural host. Journal of immunology. 2006;177:8027–8036. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.8027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu RH, Cohen M, Tang Y, Lazear E, Whitbeck JC, Eisenberg RJ, Cohen GH, Sigal LJ. The orthopoxvirus type I IFN binding protein is essential for virulence and an effective target for vaccination. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2008;205:981–992. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubio D, Xu RH, Remakus S, Krouse TE, Truckenmiller ME, Thapa RJ, Balachandran S, Alcami A, Norbury CC, Sigal LJ. Crosstalk between the type 1 interferon and nuclear factor kappa B pathways confers resistance to a lethal virus infection. Cell host & microbe. 2013;13:701–710. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bai H, Buller RM, Chen N, Green M, Nuara AA. Biosynthesis of the IFN-gamma binding protein of ectromelia virus, the causative agent of mousepox. Virology. 2005;334:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu RH, Rubio D, Roscoe F, Krouse TE, Truckenmiller ME, Norbury CC, Hudson PN, Damon IK, Alcami A, Sigal LJ. Antibody inhibition of a viral type 1 interferon decoy receptor cures a viral disease by restoring interferon signaling in the liver. PLoS pathogens. 2012;8:e1002475. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu RH, Fang M, Klein-Szanto A, Sigal LJ. Memory CD8+ T cells are gatekeepers of the lymph node draining the site of viral infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:10992–10997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701822104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Assarsson E, Greenbaum JA, Sundstrom M, Schaffer L, Hammond JA, Pasquetto V, Oseroff C, Hendrickson RC, Lefkowitz EJ, Tscharke DC, Sidney J, Grey HM, Head SR, Peters B, Sette A. Kinetic analysis of a complete poxvirus transcriptome reveals an immediate-early class of genes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:2140–2145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711573105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baldick CJ, Jr, Moss B. Characterization and temporal regulation of mRNAs encoded by vaccinia virus intermediate-stage genes. Journal of virology. 1993;67:3515–3527. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3515-3527.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taddie JA, Traktman P. Genetic characterization of the vaccinia virus DNA polymerase: cytosine arabinoside resistance requires a variable lesion conferring phosphonoacetate resistance in conjunction with an invariant mutation localized to the 3′-5′ exonuclease domain. Journal of virology. 1993;67:4323–4336. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.4323-4336.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wherry EJ, McElhaugh MJ, Eisenlohr LC. Generation of CD8(+) T cell memory in response to low, high, and excessive levels of epitope. Journal of immunology. 2002;168:4455–4461. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sykulev Y, Joo M, Vturina I, Tsomides TJ, Eisen HN. Evidence that a single peptide-MHC complex on a target cell can elicit a cytolytic T cell response. Immunity. 1996;4:565–571. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80483-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valitutti S, Muller S, Dessing M, Lanzavecchia A. Different responses are elicited in cytotoxic T lymphocytes by different levels of T cell receptor occupancy. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1996;183:1917–1921. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griffiths KL, Khader SA. Novel vaccine approaches for protection against intracellular pathogens. Current opinion in immunology. 2014;28C:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baz A, Jackson DC, Kienzle N, Kelso A. Memory cytolytic T-lymphocytes: induction, regulation and implications for vaccine design. Expert review of vaccines. 2005;4:711–723. doi: 10.1586/14760584.4.5.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Remakus S, Rubio D, Lev A, Ma X, Fang M, Xu RH, Sigal LJ. Memory CD8(+) T cells can outsource IFN-gamma production but not cytolytic killing for antiviral protection. Cell host & microbe. 2013;13:546–557. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.