Summary

Although challenging, adults can learn non-native phonetic contrasts with extensive training [1, 2], indicative of perceptual learning beyond an early sensitivity period [3, 4]. Training can alter the low-level sensory encoding of newly acquired speech sound patterns [5]; however, the time-course, behavioral-relevance, and long-term retention of such sensory plasticity is unclear. Some theories argue that sensory plasticity underlying signal enhancement is immediate and critical to perceptual learning [6, 7]. Others, like the reverse hierarchy theory (RHT), posit a slower time-course for sensory plasticity [8]. RHT proposes that higher-level categorical representations guide immediate, novice learning; while lower-level sensory changes do not emerge until expert stages of learning [9]. We trained 20 English-speaking adults to categorize a non-native phonetic contrast (Mandarin lexical tones) using a criterion-dependent sound-to-category training paradigm. Sensory and perceptual indices were assayed across operationally-defined learning phases (novice, experienced, over-trained, and 8-week retention) by measuring the frequency-following response, a neurophonic potential that reflects fidelity of sensory encoding, and the perceptual identification of a tone continuum. Our results demonstrate that while robust changes in sensory encoding and perceptual identification of Mandarin tones emerged with training and were retained, such changes followed different timescales. Sensory changes were evidenced and related to behavioral performance only when participants were over-trained. In contrast, changes in perceptual identification reflecting improvement in categorical percept emerged relatively earlier. Individual differences in perceptual identification, and not sensory encoding, related to faster learning. Our findings support the RHT: sensory plasticity accompanies, rather than drives, expert levels of non-native speech learning.

Keywords: perceptual learning, plasticity, perceptual identification, sensory encoding, frequency-following response, auditory, reverse hierarchy theory

In Brief

Reetzke et al. show that as adults are trained to categorize non-native speech sounds, sensory encoding of non-native speech sound patterns improves only after an expert-level of behavioral performance. Training-induced changes in sensory encoding relate to behavioral performance and endure beyond the period of training.

Results and Discussion

Sound-to-category training paradigm

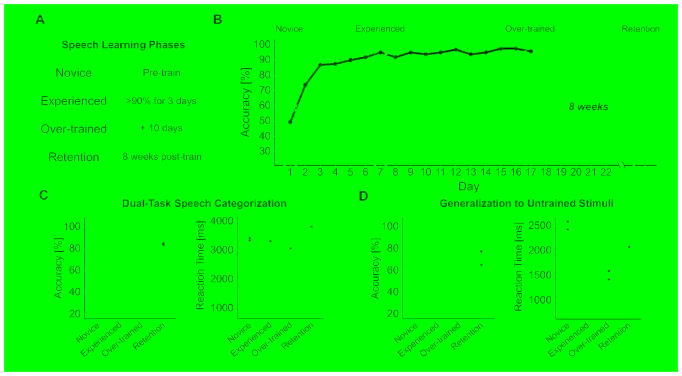

We trained 20 native English-speaking adults using a criterion-dependent sound-to-category training paradigm (see STAR Methods) [10]. As shown in Figure 2, A and B, each participant was monitored across three operationally defined learning phases until criterion behavioral performance was achieved and maintained. Participants were considered novice during the first training session. Participants took 4–13 days (M = 7.10, SD = 2.81) to reach the experienced learning phase, which was defined as maintaining behavioral accuracy comparable to native Mandarin participants (> 90% accuracy) for three consecutive days. Participants were then over-trained for ten additional days beyond the experienced phase to ensure stability in behavioral categorization. After 8-weeks post-training, retention of speech categorization expertise was evaluated [11]. To further test participants’ behavioral mastery of Mandarin lexical tone categorization, at each phase we probed learning through two secondary tasks (Figure 1B): speech categorization under a dual-task constraint and generalization to untrained stimuli.

Figure 2. Operationally defined speech learning phases and behavioral results.

(A) The four speech learning phases defined. (B) Subject-by-day learning curves (n = 20) from the speech training task. The gray rectangle denotes ± SEM for Chinese participants (target criterion for learners); the dashed gray line indicates chance level (25% accuracy) for Mandarin lexical tone categorization. The emphasized black learning curve is a representative participant tracked across all learning phases. Accuracy and median reaction time results across learning phases for (C) speech categorization under dual-task constraint and (D) generalization to untrained stimuli. The center line on each box plot denotes the median accuracy or reaction time, the edges of the box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the whiskers extend to data points that lie within 1.5 times the interquartile range. Points outside this range represent outliers. Gray rectangles denote ± SEM for Chinese participants.

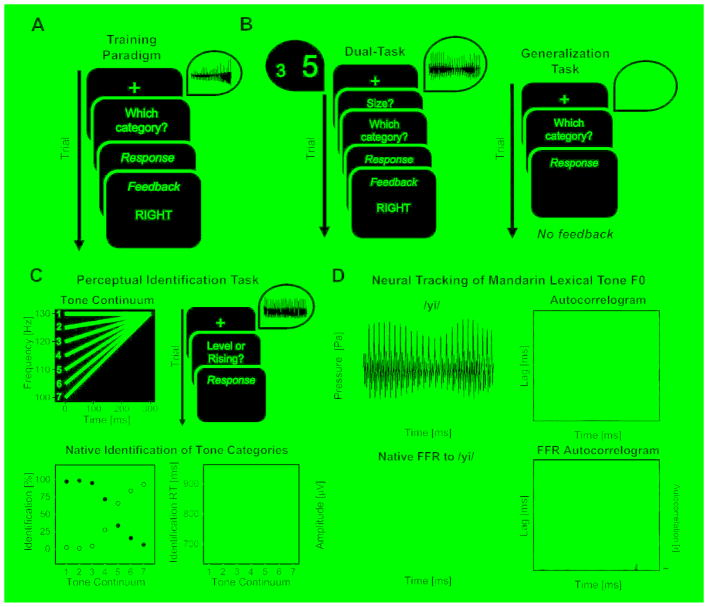

Figure 1. Experimental Methods.

(A) Trial procedure for the sound-to-category training task. Each trial began with a fixation cross in the center of the screen for 750 ms. A Mandarin lexical tone was presented for a fixed duration (440 ms). Participants were given unlimited time to categorize the tone into categories 1, 2, 3 or 4. Corrective feedback (1000 ms) was presented 500 ms following participants’ response. (B) Dual-Task (left) required participants to make ‘value' and ‘size' judgment responses while categorizing the Mandarin lexical tones. The generalization task (right) required participants to categorize stimuli produced by untrained speakers (denoted by the blue waveform). (C) Perceptual Identification Task. At the top, the seven-step tone continuum from the level (red) to the rising (blue) Mandarin lexical tone, and the trial procedure used to probe perceptual identification of tone categories (see STAR Methods). At the bottom, the average identification function from native Mandarin participants (n = 13) and identification reaction times for tone identification. Closed and open circles correspond to mean identification percentage for the level and rising Mandarin lexical tones, respectively. Despite the continuous acoustic change, native Mandarin speakers exhibit a steep perceptual identification slope near the category boundary at the midpoint of the continuum (tone token 4), and are slower to label stimuli near the boundary [51–53]. Shaded areas and error bars denote ± SEM. (D) Neural Tracking of Mandarin Lexical Tone F0. Waveform and autocorrelogram of an example Mandarin lexical tone (top), and corresponding frequency-following response (FFR) and autocorrelogram from a native Mandarin speaking participant (bottom). The autocorrelogram provides visualization of autocorrelation over a 40-ms sliding window, and allows an estimation of the extent to which the FFR follows F0 changes characterizing the Mandarin tone stimulus (see STAR Methods). The colors represent the strength range of the correlation from high (white; value = 1) to low (dark red; value = −1).

To examine training-induced changes in perceptual identification, we assayed identification accuracy and reaction times for tones drawn randomly from a seven-step tone continuum that ranged from the level to the rising Mandarin lexical tone (Figure 1C). To examine training-induced changes in sensory encoding of non-native speech sound patterns, we measured neural tracking of the four Mandarin lexical tone fundamental frequency (F0) contours using the frequency-following response (Figure 1D), a pre-attentive measure of synchronous sound-evoked neural activity that encodes acoustic details of the incoming stimulus along the early auditory pathway (see STAR Methods) [12–14]. English learners' performance on all tasks was compared to native Chinese participants whose categorization performance was used to establish the training criterion.

Speech categorization under dual-task constraint

One standard for determining mastery of perceptual learning is to examine the extent to which that behavior is automatic, or maintained while performing another task in parallel under a dual-task constraint [15–17]. As demonstrated in Figure 2C, initially learners’ speech categorization under dual-task constraint significantly differed from native participants [accuracy: b = −0.399, SE = 0.036, t = −11.117, p < 0.001; reaction time: b = 586.100, SE = 192.840, t = 3.039, p = 0.004]. However, once learners reached the experienced phase, speech categorization was not statistically different from native participants [accuracy: b = −0.037, SE = 0.036, t = −1.028, p = 0.307; reaction time: b = 260.200, SE = 192.840, t = 1.349, p = 0.183]. This high level of performance was maintained at the over-trained phase [accuracy: b = −0.018, SE = 0.036, t = −0.490, p = 0.626; reaction time: b = 61.000, SE = 192.840, t = 0.316, p = 0.753], and retained 8-weeks post-training [accuracy: b = −0.038, SE = 0.036, t = −1.046, p = 0.299; reaction time: b = 67.150, SE = 192.840, t = 0.348, p = 0.729].

Generalization to untrained stimuli

A critical test of the mastery of perceptual learning is the extent to which learning generalizes beyond trained stimuli [11]. As shown in Figure 2D, novice learners significantly differed in categorization of untrained stimuli relative to native participants [accuracy: b = −0.400, SE = 0.036, t = −11.124, p < 0.001; reaction time: b = 444.160, SE = 99.750, t = 4.453, p < 0.001]. Once learners reached the experienced phase, performance was not statistically different from native participants [accuracy: b = −0.056, SE = 0.036, t = −1.565, p = 0.121; reaction time: b = 170.720, SE = 99.750, t = 1.711, p = 0.092]. Maintenance of performance was observed at the over-trained learning phase [accuracy: b = −0.039, SE = 0.036, t = −1.078, p = 0.287; reaction time: b = 35.770, SE = 99.750, t = 0.359, p = 0.721], and retained 8-weeks post-training [accuracy: b = −0.068, SE = 0.036, t = −1.878, p = 0.064; reaction time: b = 59.850, SE = 99.750, t = 0.600, p = 0.551].

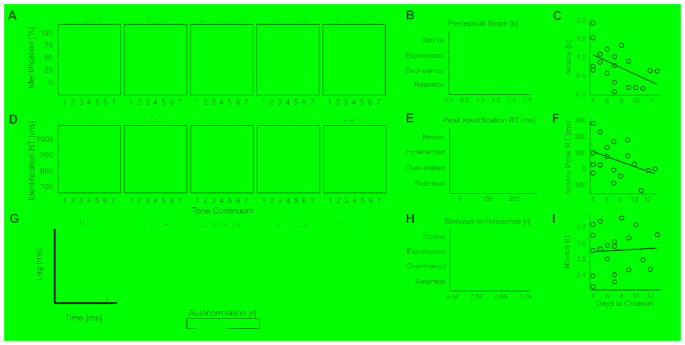

Training-induced changes in perceptual identification of tone categories

At each learning phase we measured the extent to which perceptual identification became more categorical as a function of learning phase, by measuring the slope of the tone identification labeling curve (perceptual slope) and peak of identification reaction times (peak RT; see STAR Methods). Tone identification labeling curves and reaction times are shown for each learning phase relative to native performance in Figure 3, A and D, respectively. Before training, novice learners exhibited a shallower perceptual slope and invariant identification reaction times across the tone continuum, compared to native participants [perceptual slope: b = −1.226, SE = 0.306, t = −4.003, p < 0.001; peak RT: b = −150.140, SE = 71.790, t = −2.091, p = 0.039]; however, once learners reached the experienced phase, they demonstrated a steeper perceptual slope and slowing of reaction times at the categorical boundary; this performance was not statistically different from native participants [perceptual slope: b = −0.278, SE = 0.306, t = −0.907, p = 0.367; peak RT: b = −79.810, SE = 71.790, t = −1.112, p = 0.270]. Perceptual identification of tone categories was maintained at the over-trained learning phase [perceptual slope: b = −0.112, SE = 0.306, t = −0.367, p = 0.715; peak RT: b = −31.590, SE = 71.790, t = −0.440, p = 0.661], and retained after 8-weeks post-training [perceptual slope: b = −0.419, SE = 0.306, t = −1.369, p = 0.175; peak RT: b = 58.680, SE = 71.790, t = 0.817, p = 0.416].

Figure 3. Training-induced changes in perceptual identification of tone categories and sensory encoding of Mandarin lexical tone F0 contours.

(A) Perceptual identification functions across all learning phases relative to native Mandarin speaking participants. Closed and open circles correspond to mean identification percentage for the level and rising Mandarin lexical tones, respectively. Shading denotes ± SEM. (B) Comparison of steepness of the perceptual identification slope across learning phases. (C) Individuals with a sharper perceptual slope at the novice learning phase require fewer days of training to reach the criterion level (rs = −0.519, p = 0.023). (D) Identification reaction times for tone identification. Error bars denote ± SEM. See also Table S1. (E) Comparison of peak of identification reaction time (or slowing) at the categorical boundary. (F) Relationship between novice peak of identification RT and days to reach training criterion (rs = −0.351, p = 0.153). (G) Autocorrelogram function to Mandarin lexical tone 3 for a native Mandarin participant relative to a representative English learner across all four learning phases. Robust improvement in neural phase-locking (peak autocorrelation) to Mandarin tone F0 is not observed until after behavior is stable (at the over-trained learning phase). (H) Mean neural tracking accuracy of the F0 contour of all Mandarin tone stimuli as reflected by stimulus-to-response correlation across learning phases. Changes in stimulus-to-response correlation are not observed until the over-trained learning phase. For both neural metrics, plasticity is not tone-specific and is retained after 8-weeks of no training. (I) In contrast to perceptual identification slope, novice stimulus-to-response correlation (as well as peak autocorrelation, not shown) does not significantly predict days to criterion (rs = 0.091, p = 0.702). On all bar graphs, gray rectangles denote ± SEM for native Mandarin performance and error bars denote ± SEM.

Training-induced changes in sensory encoding of Mandarin lexical tone F0 contours

At each learning phase, we measured the FFR to assess changes in neural tracking of the F0 of each of the four Mandarin lexical tones with two well-established metrics: peak autocorrelation, which reflects the robustness of neural phase locking to the F0 contour, and stimulus-to-response correlation, which reflects neural fidelity of F0 tracking [12] (see STAR Methods). Analyses focused on neural tracking of Mandarin tone F0 contours across learning phases, as this is the dominant cue for tonal recognition in native Mandarin speakers [5, 18–21].

A repeated measures ANOVA on both metrics showed a main effect of learning phase [peak autocorrelation: F3, 57 = 3.49, p = 0.033, ηp2 = 0.16; stimulus-to-response correlation: F3, 57 = 4.28, p = 0.013, ηp2 = 0.18] and tone stimulus [peak autocorrelation: F3, 57 = 32.99, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.63; stimulus-to-response correlation: F3, 57 = 38.85, p < 0.001, ηp2= 0.67]. The interaction between learning phase and tone stimulus did not reach significance for either metric [peak autocorrelation: F9, 171 = 1.46, p = 0.203, ηp2= 0.07; stimulus-to-response correlation: F9, 171 = 0.77, p = 0.589, ηp2= 0.04].

Planned comparisons showed that gain in peak autocorrelation did not emerge until the over-trained learning phase (Figure 3G) [over-trained vs. novice: t19 = 2.05, p = 0.054, d = 0.20; experienced vs. novice: t19 = 0.42, p = 0.679, d = 0.04]. Likewise, stimulus-to-response correlation also did not increase until the over-trained learning phase (Figure 3H) [over-trained vs. novice: t19 = 3.88, p = 0.001, d = 0.34; experienced vs. novice: t19 = 0.39, p = 0.669, d = 0.04]. Gains in neural phase-locking and neural tracking persisted after 8-weeks post-training, as evidenced by stability between the over-trained and retention learning phases [peak autocorrelation: t19 = 0.80, p = 0.435, d = 0.08; stimulus-to-response correlation: t19 = 0.59, p = 0.562, d = 0.07].

We performed Welch two-sample t-tests (Bonferroni-corrected) to compare learners’ sensory encoding of Mandarin lexical tones at each learning phase to native participants. For the peak autocorrelation metric, learners initially differed from native participants in robustness of neural phase locking to the F0 contour of the Mandarin tone stimuli [novice vs. native: t30.67 = 2.72, p = 0.010, d = 0.70; experienced vs. native: t30.30 = 2.60, p = 0.014, d = 0.65]; however, once learners reached the over-trained phase, neural phase locking was not statistically different from native participants [over-trained vs. native: t30.90 = 1.87, p = 0.071, d = 0.49]. This high level of performance was retained after 8-weeks post-training [retention vs. native: t29.43 = 1.69, p = 0.101, d = 0.41]. For the stimulus-to-response correlation metric, learners initially differed from native participants in neural tracking of the Mandarin F0 patterns [novice vs. native: t28.46 = 3.72, p = 0.001, d = 0.70; experienced vs. native: t29.22 = 3.40, p = 0.002, d = 0.65]; however, once learners reached the over-trained phase stimulus-to-response correlation was not statistically different from native participants [over-trained vs. native: t30.54 = 1.66, p = 0.108, d = 0.34]. Statistical difference between groups was observed at retention [retention vs. native: t30.06 = 2.09, p = 0.045, d = 0.41].

Sensory and perceptual predictors of days to speech learning criterion

We investigated the extent to which novice measures of perceptual identification and neural tracking of Mandarin lexical tone F0 patterns predicted days to the experienced criterion. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients revealed that participant’s novice perceptual slope negatively related to days to experienced criterion (rs = −0.519, p = 0.023), suggesting that individuals with a sharper pre-training perceptual slope required fewer days to criterion (Figure 3C). While peak identification reaction time was not significantly predictive of days to criterion (rs = −0.351, p = 0.153), the trend of the correlation was in a similar direction (Figure 3F). Neither of the neural tracking metrics significantly related to days to reach criterion [stimulus-to-response correlation: rs = 0.091, p = 0.702; peak autocorrelation: rs = −0.111, p = 0.641] (Figure 3I).

Patterns of sensory encoding predict patterns of behavioral speech categorization

To investigate the relationship between sensory encoding and behavioral categorization of the Mandarin lexical tones across learning phases, we used a hidden Markov classifier to decode tone categories from the FFRs of each participant (see STAR Methods). Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was calculated to relate the neural confusion matrix provided by the unsupervised classifier with behavioral patterns of speech categorization from each participant's generalization task performance (Figure 4A). We found that the relationship between individual patterns of neural decoding and behavioral patterns of untrained tone categorization increased across learning phases (Figure 4B) [F3, 57 = 6.60, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.26]. The neural-behavioral relationship did not show an improvement until the over-trained learning phase [over-trained vs. novice: t19 = 2.79, p = 0.012, d = 0.90; experienced vs. novice: t19 = 2.06, p = 0.054, d = 0.59]. Gains in neural-behavioral correspondence persisted after 8-weeks post-training, as evidenced by stability between the over-trained and retention learning phases [over-trained vs. retention: t19= −0.69, p = 0.497, d = 0.20].

Figure 4. Patterns of sensory encoding predict patterns of behavioral speech categorization.

(A) Neural confusion matrices derived from a hidden Markov Model classifier which was trained and tested on FFRs to the Mandarin lexical tones (top), and behavioral confusion matrices derived from generalization Mandarin lexical tone categorization performance from a representative English learner. Each matrix corresponds to a learning phase; each row corresponds to predicted Mandarin tone category responses, and each column corresponds to the correct Mandarin tone category. The color of a given cell denotes the proportion of the category-response combination within a given learning phase and ranges from high (red; value = 1.0) to low (blue; value = 0.0). Higher values within the diagonal cells, extending from bottom left to top right corner of the matrix, correspond to correct responses; other cells denote errors. (B) The relationship between individual neural and behavioral confusions matrices as reflected by Spearman's rho. The gray rectangle denotes ± SEM for native Chinese participants. The center line on each box plot denotes the median accuracy or reaction time, the edges of the box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the whiskers extend to data points that lie within 1.5 times the interquartile range. Points outside this range denote outliers.

Welch’s two-sample t-tests (Bonferroni-corrected) revealed that, novice learners exhibited significantly less neural-behavioral correspondence relative to native Chinese participants [t23.84 = −4.05, p < 0.001, d = 1.31]. Once learners reached the over-trained phase, patterns of sensory encoding related to patterns of behavioral categorization, and were not statistically different from native participants [over-trained vs. native: t27.24 = −1.35, p = 0.188, d = 0.44; experienced vs. native: t26.42 = −2.108, p = 0.045, d = 0.70]. This high level of neural-behavioral correspondence was retained 8-weeks post-training [over-trained vs. retention: t30.56 = −1.050, p = 0.302, d = 0.35.]

General Discussion

We examined the time-course, behavioral-relevance, and long-term retention of changes in sensory encoding of non-native speech sound patterns as adults learned to categorize a non-native phonetic contrast across different phases of speech learning expertise. Our results show that learners reached criterion based on native performance, maintained behavioral performance under dual-task constraint and generalized performance to untrained stimuli; satisfying rigorous standards for perceptual learning mastery [11, 15–17]. While changes in the perceptual identification of tone categories were evidenced at the experienced learning phase, significant changes in sensory encoding of untrained Mandarin lexical tones emerged only after the over-trained learning phase (Figure 3). Correspondence between patterns of sensory encoding and behavioral categorization of Mandarin lexical tones were also strongly related at this phase. Despite the different timescales for perceptual and sensory plasticity, after 8-weeks post-training, both perceptual changes and sensory encoding gains were retained. Our findings suggest that sensory enhancement of incoming stimulus features is not critical for early stages of speech perceptual learning. Rather, in line with the reverse hierarchy theory (RHT), we posit that enhanced sensory encoding observed at a later learning phase is an outcome of perceptual mastery.

Our results diverge from theories that suggest that perceptual learning is primarily driven by sensory processing enhancement [6, 7, 22], but closely align with the RHT which indicates low-level sensory enhancement emerges at expert stages of perceptual learning [9, 23, 24]. Consistent with RHT, we posit that novice performance is guided by abstract categorical representations [8, 9], likely the result of receptor-field plasticity at higher-levels of the sensory processing hierarchy [25]. The emergence of categorical percept may facilitate the top-down guided tuning of lower-levels of the auditory hierarchy with the goal of signal enhancement. In line with this idea, animal models have revealed top-down gated sensory enhancement of selective features of incoming acoustic stimuli following extensive behaviorally-relevant training [26–28]. Our findings suggest that native listeners and over-trained learners may be able to operate at the level of category-based perception and reach down to lower-levels of the sensory hierarchy for tuning of behaviorally-relevant signals, depending on the nature of the task [29, 30]. Learners who demonstrated better perceptual identification of tone categories (thought to reflect higher-level attention-driven processes [31]) at the novice learning phase, took fewer days to reach the learning criterion (Figure 3C). In contrast, measures of neural tracking of non-native speech sound patterns did not relate to faster learning (Figure 3I). Taken together, these studies and our findings, suggest that slow changes observed in the sensory encoding of relevant stimulus features (i.e., Mandarin lexical tone F0 contours) may be an outcome of sensory tuning guided by expertise in higher-level categorical perception.

Previous studies using the FFR as a metric have revealed training-induced enhancement in sensory encoding of non-native speech sound patterns in human adults [5, 18, 32]; however, the neurophysiological changes observed have been restricted to specific tones [5] or selective portions of the incoming stimulus [33]. A limitation of previous studies is the large individual differences in learning, likely arising from circumscribed training regimens [5]. In contrast, the present study demonstrated that training-induced improvement in sensory encoding following an individually focused, criterion-driven approach, is not tone-specific, with overall sensory enhancement observed and retained. This approach allowed for a systematic examination of the neurophysiological changes underlying different phases of perceptual learning expertise, as all participants were trained to similar levels of behavioral performance. Our training paradigm additionally combined high-variability stimuli and reinforcement driven learning via trial-by-trial feedback; training components found to direct participant attention to category-relevant acoustic cues and lead to long-lasting behavioral retention [34–36]. Animal models have demonstrated that receptive field properties of neurons in the primary auditory cortex (A1) [37, 38] and the inferior colliculus [39] undergo task-related changes in stimulus-response strength as a result of associative learning. These changes have been connected to dopaminergic projections to A1, activated by associations between incoming stimuli and reinforcers (e.g., reward or punishment) [40, 41]. In line with these findings, a neuroimaging study in adult humans showed that reward based neural circuitry (i.e., caudate, putamen, and ventral striatum) is activated more in successful learners of a similar speech sound-to-category training task [10]. We posit that the combination of high-talker variability and reinforcement driven learning, paired with a criterion-driven approach facilitated behavioral mastery and retention of non-native speech sound learning in adults, and led to non-tone specific improvement in sensory encoding of non-native speech sound patterns.

Despite the different timescales for behavioral and neural plasticity, our findings reveal long-term retention beyond the period of training for both behavioral gains in non-native speech sound categorization and refined sensory encoding of incoming stimulus features. These results are consistent with prior work demonstrating long-term retention of training-induced receptive field reorganization within A1 following extensive auditory discrimination training [40]. Consistent with our findings, sensory encoding gains were observed 8-weeks post-training [38, 42]. In contrast, animal studies investigating auditory and motor training have demonstrated that while cortical plasticity develops through initial learning stages, such changes may renormalize as behavior stabilizes [43, 44]. This body of work suggests that maintenance and retention of trained performance may be localized to specific neural circuitry rather than in retention of large-scale expansion of tissue in a given neural region [14, 45–47]. While our study cannot speak to the extent to which physiological changes in cortical plasticity was induced or retained, our results suggest that maintenance and retention of sensory encoding of incoming stimulus features, as reflected by the FFR, may be an outcome of training-induced rewired neural circuitry [48, 49]. Furthermore, we observed a strong relationship between patterns of sensory encoding and behavioral categorization at later learning phases and at retention (Figure 4). This strong correspondence suggests that while signal enhancement may not be critical during early stages of perceptual learning; such sensory plasticity is not epiphenomenal. Rather, in line with RHT, we posit that sensory plasticity may be a critical component of behavioral stability and flexibility. For example, under challenging listening conditions, experts may be able to leverage the enhanced signal-to-noise ratio to maintain stability in behavioral performance [50].

Language-specific changes in perception and sensory encoding of speech sounds occurs early in life; however, with intensive training adults can achieve remarkable degrees of learning and retention of non-native phonetic contrasts. Consistent with the RHT, we show that as adults learn non-native phonetic contrasts, sensory encoding is fine-tuned, and accompanies, rather than drives, expert levels of behavioral perceptual identification. We further provide evidence for training-induced neurophysiological changes in sensory encoding that relate to behavioral stability, and endure beyond a period of intensive training. Our findings are in support of an emerging view that auditory perceptual learning is mediated by top-down processes that shape sensory signals through later learning phases [30].

STAR Methods

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Bharath Chandrasekaran (bchandra@utexas.edu).

SUBJECT DETAILS

Twenty-two native English speaking adults (12 female; mean age = 20.9 yr, SD = 4.1 yr) were recruited to participate in the training study. Two participants did not complete all learning stages. One participant chose not to finish the training before criterion was met. The other participant did not demonstrate significant learning in the first 12 days of participation in the experiment, and therefore never progressed beyond the novice stage of learning. This participant was provided a choice to terminate or continue training and chose the former. Fifteen native Mandarin-speaking adults (10 female, mean age = 24.0 yr, SD = 2.7 yr) were recruited to participate in a single day of behavioral testing to establish learning criterion for the English learners. We collected frequency-following responses (FFRs) to the four Mandarin tones (described below) and perceptual identification data from 13 of these participants. The FFR data from the native Mandarin speakers reported in this article was presented in a recent methods-related publication as part of the development of a novel machine learning algorithm to study the FFR [54]. Native English speaking participants reported that they were monolingual and had no previous exposure to or experience with a tonal language. All participants reported no current or previous history of a neurodevelopmental disorder or hearing deficit and no use of neuropsychiatric medication. Participants had normal hearing defined as air conduction thresholds < 20 dB HL at octave frequencies from 250 to 8,000 Hz measured by an Interacoustics Equinox 2.0 PC-Based Audiometer. Previous evidence has shown that music training influences the neural representation of non-native linguistic pitch patterns [19, 55, 56]. Therefore, participants with significant musical experience were excluded from participation in this study (all participants had < 6 yrs of continuous music training and were not currently practicing). We did not include a group of English participants that experienced passive exposure to Mandarin tones because previous evidence shows that extensive passive exposure to thousands of trials of Mandarin lexical tones over multiple days of recording does not modify participant neural tracking of Mandarin lexical tone F0 contours [21]. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Texas at Austin approved all materials and procedures, and all procedures were carried out following the approved guidelines. Written consent was obtained from all participants before participation in the study. All participants were recruited from the University of Texas at Austin community and received $15/hr monetary compensation for their participation.

METHOD DETAILS

Sound-to-Category Training Task

The sound-to-category training paradigm included high-variability stimuli and reinforcement via instructional feedback (Figure 1A), two training components found to direct participant attention to category-relevant acoustic cues [34–36], facilitating learning and long-lasting retention. The stimuli used in the speech training paradigm consisted of the four Mandarin lexical tones, which differ in their fundamental frequency (F0) contour: tone 1 (high-level), tone 2 (low-rising), tone 3 (low-dipping), and tone 4 (high-falling). Each tone was produced by two native Mandarin Chinese speakers (1 female), originally from Beijing, in the context of five syllables (bu, di, lu, ma, and mi). The 40 stimuli were normalized for root-mean-square (RMS) amplitude at 70 dB sound pressure level (SPL) and 440 ms duration. These stimuli were identical to the stimuli we have used in previous experiments [10, 21, 57].

Participants were instructed to categorize each stimulus into 1 of 4 categories by pressing the number keys (1, 2, 3 or 4) on a keyboard, corresponding to tone 1, tone 2, tone 3, and tone 4, respectively. No other instructions were provided. Each trial began with a fixation cross in the center of the screen for 750 ms. The stimulus was presented binaurally through Sennheiser HD 280 Pro circumaural headphones. After responding, participants were given feedback that was displayed for 1,000 ms. The response-to-feedback interval was fixed at 500 ms. The content of feedback was dependent on the accuracy of the response (“RIGHT” vs. “WRONG”). Participants had unlimited time to respond, and the task moved on to the next trial once the participant input a response. Stimulus presentation, feedback, participant response, and reaction time (RT) measurement were controlled and acquired using MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA).

Dual-Task: Speech Categorization + Numerical Stroop

Participants simultaneously categorized tone stimuli while performing a numerical Stroop Task to test the emergence of ‘automaticity’ in performance [15, 16, 58]. Participants completed the dual-task during each learning phase (novice, experienced, over-trained) and at retention. The speech categorization stimuli in the dual-task were the same as those used in the sound-to-category training task. Participants were instructed that their goal was to remember which digit was larger in value, and which digit was larger in size. Each trial (80 trials in total) began with a fixation cross that appeared in the center of the screen for 750 ms. Two different digits (ranging from 2 to 8) were then randomly presented on the left and right sides of the screen at each trial as the tone stimulus was presented binaurally through Sennheiser HD 280 Pro circumaural headphones. One of the digits was displayed in a larger font relative to the other digit. At the end of each trial, participants would make a speech categorization response, as they did in the sound-to-category training and speech category generalization tasks. Before speech categorization, participants were cued either by the word “Size” or the word “Value.” If the cue was “Size,” the participant needed to indicate whether the digit of the larger size was on the right or the left of the fixation cross. If the cue was “Value” the participant needed to indicate whether the digit of the larger value was on the right or left of the fixation cross. Participants were instructed to focus on the new task and to perform the speech categorization task with the attentional resources they had left. Participants had unlimited time to respond and self-initiated to the next trial. Stimulus presentation, participant response, and RT measurement were controlled and acquired using MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA).

Generalization Task

The generalization task utilized an untrained set of 40 stimuli that were not used in the sound-to-category training task. The stimuli were derived from two untrained native Mandarin Chinese speakers (1 female), originally from Beijing, who produced the four Mandarin tones in citation form in the context of the same five syllables used in the training task. The 40 stimuli were normalized for RMS amplitude at 70 dB SPL and 440 ms duration. The trial procedure for the generalization task was consistent with the sound-to-category training task, with the exception that participants did not receive feedback after categorization responses. Participants had unlimited time to respond and self-initiated to the next trial. Stimulus presentation, participant response, and RT measurement were controlled and acquired using MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA).

Perceptual Identification Task

While tonal language speakers perceive discrete tone categories across a tone continuum, non-tonal language speakers do not [51–53, 59]. Compared to non-tonal language speakers, tonal language speakers demonstrate a steeper identification labeling curve (perceptual slope); and greater peak in identification reaction time (peak RT) at the category boundary, where between-category distinctions become ambiguous [51–53, 59]. To assess the training-induced changes in categorical perception of Mandarin lexical tone categories, participants completed a perceptual identification task during each learning phase (novice, experienced, over-trained) and at retention.

Stimuli consisted of a tone continuum identical to the continuum used in [59], where tone tokens were created to differ minimally acoustically but could be perceived categorically by native tonal language speakers [59]. The continuum was constructed by generating seven 300 ms tokens ranging in equal steps from the level to rising Mandarin lexical tone F0 contours. The F0 contours of the tone continuum were modeled by seven linear functions (see [59]). The resulting stimuli all had the same offset frequency (130.00 Hz), and therefore only differed in onset frequency [Step 1: 130.00 Hz; Step 2: 125.15 Hz; Step 3: 120.38 Hz; Step 4: 115.70 Hz; Step 5: 111.08 Hz; Step 6: 106.55 Hz; Step 7: 102.08 Hz]. The F0 contours of the stimuli are shown in Figure 1C.

Each stimulus was presented binaurally to participants via insert earphones (ER-3; Etymotic Research, Elk Grove Village, IL). Participants were instructed to press ‘1' if they heard a “level” pitch, or ‘2' if they heard a “rising” pitch. No feedback was provided to the participants. Each of the seven stimuli was randomly presented to each participant 20 times for a total of 140 trials. Participants had unlimited time to respond. After the participant made a response, the task moved on to the next trial following a 1000 ms delay.

Electrophysiology

Participants completed an electrophysiology session at each learning phase (novice, experienced, over-trained) and during retention. We recorded the frequency-following response (FFR), which is a sound-evoked response that mirrors the acoustic properties of the incoming acoustic signal with remarkable fidelity [5, 12, 60–63]. The FFR is considered an integrated response resulting from an interplay of early auditory subcortical and cortical systems [13, 14], shows high test-retest stability [12, 21, 63, 64], and robustly reflects long-term experience-dependent plasticity in native speakers of Mandarin [55, 65–67], as well as training-induced plasticity [5, 18, 19, 21, 60].

Stimuli

The stimuli consisted of four 250 ms synthetic tones minimally distinguished by their F0 contour (tone 1, tone 2, tone 3, and tone 4). The synthesis was derived from natural male production data. These stimuli were not used in the sound-to-category training, dual-task, and speech category generalization task. The four tones were superimposed over the same syllable /yi/, and only differed in their F0 contour: yi1 high-level [tone 1], with F0 equal to 129 Hz; yi2 low-rising [tone 2], with F0 rising from 109 to 133 Hz; yi3 low-dipping [tone 3], with F0 onset falling from 103 to 89 Hz and F0 offset rising from 89 to 111 Hz; and yi4 high-falling [tone 4], with falling F0 from 140 to 92 Hz. All tones were normalized to the same RMS amplitude at 72 dB SPL and duration at 250 ms.

Acquisition and Preprocessing

At each learning phase, participants sat in an acoustically attenuated booth and watched a muted movie or television show of their choice with subtitles. Electrophysiological responses to the Mandarin tone stimuli were collected using Ag-AgCl scalp electrodes, with the active electrode placed at the central zero (Cz) point, the reference at the right mastoid, and the ground at the left mastoid. Contact impedance was < 5 kΩ for all electrodes for all recording sessions, and responses were recorded at a sampling rate of 25 kHz using Brain Vision PyCorder 1.0.7 (Brain Products, Gilching, Germany). Alternating polarities of the stimuli were binaurally presented via insert earphones (ER-3; Etymotic Research, Elk Grove Village, IL), with an inter-stimulus interval jittered between 122 to 148 ms. Consistent with previous studies, participants were instructed to ignore the sounds, focus on the selected movie or television show, and refrain from extraneous movement. The four Mandarin lexical tones were presented in separate blocks, and the order of blocks was counterbalanced across participants. Stimulus presentation was controlled by E-Prime 2.0.10 software [68].

The electrophysiological data were preprocessed with BrainVision Analyzer 2.0 (Brain Products, Gilching, Germany). Responses were off-line bandpass filtered from 80 to 1,000 Hz (12 dB/octave, zero phase-shift). The bandpass filter approximately reflects the lower and upper limits of phase-locking along the auditory pathway that contributes to the FFR (auditory cortex, midbrain). Responses were then segmented into epochs of 310 ms (40 ms before stimulus onset and 20 ms after stimulus offset), and baseline corrected to the mean voltage of the noise floor (−40 to 0 ms). Epochs in which the amplitude exceeded ±35 μV were considered artifacts and rejected. At each stage of learning, 1,000 artifact-free FFR trials (500 for each polarity) were obtained for each Mandarin lexical tone from all participants.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Evaluation of Changes in Perceptual Identification of Tone Categories

We evaluated the extent to which perceptual identification of tone categories changed as a function of training, by obtaining three well-established measures from each subject at each learning phase: category boundary, the slope of the identification curve, and the peak of identification reaction time (RT). To calculate the category boundary and the slope of the identification curve, we fitted a logistic regression model on the tone identification function on an individual subject basis, consistent with prior work [59, 69], with the following formula:

Where y refers to the proportion of participant responses that indicate “rising” pitch (ranging from 0 to 100%), x refers to the onset frequency of the stimulus’ F0 contour, c refers to the category boundary where the proportion to report the tone as a “rising” pitch was 50%, and b refers to slope of the fitted logistic function and indicates the sharpness of the categorical boundary. Note that the tone identifications for “level” and “rising” responses are symmetrical, and therefore, only the “rising” responses were used in the current analysis. The model estimation procedures were conducted in R via the nlsLM function [70] that implemented the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm [71] to search for the optimal parameters (b and c) that provide the best fit between the logistic model and the actual value y. Identification reaction times (RTs), also referred to as behavioral speech labeling speeds, were calculated as listeners’ mean response latency across trials at each learning phase. In line with [53], RTs outside of 250–3500 ms were considered outliers and excluded from further analysis. To calculate the peak of identification RT, we estimated the difference of between-category perceptual sensitivity and within-category perceptual sensitivity [59]. Where between-category perceptual sensitivity was measured as identification RT from the categorical boundary (tone token 4) of the identification function; and within-category sensitivity was taken as the average identification RT near the ends of the tone continuum (tone tokens 2 and 6).

Evaluation of Changes in Neural Tracking of Mandarin Lexical Tone F0 Patterns

We evaluated the extent to which the FFRs follow F0 changes in the Mandarin lexical tone stimuli by extracting the F0 contour from the 1000-trial averaged FFRs using a periodicity detection short-term autocorrelation algorithm [72]. This algorithm works by sliding a 40-ms window over the time course of the FFR (10 to 260 ms post-stimulus onset). The 40-ms sliding window was shifted in 10 ms steps, to produce a total of 22 overlapping bins. The maximum (peak) autocorrelation value (ranging from −1 to 1) was searched over a lag value of 4 to 14.3 ms at each bin, a range that encompasses the time-variant periods of the F0 contours for the Mandarin tone stimuli. The peak autocorrelation value, as well as the corresponding lag, were recorded for each bin. The reciprocal of this time lag (or pitch period) was calculated to estimate the F0 for each bin. The resulting frequency values were concatenated to form a 22-point running F0 contour. The short-term autocorrelation algorithm was applied to both the FFRs and the Mandarin tone stimuli. Pitch tracking accuracy metrics were then computed using the F0 contour extracted from the FFRs and the F0 contour extracted from the stimuli.

Classification of FFRs to Mandarin Lexical Tones

Mandarin lexical tone categories were decoded from individual FFRs using the hidden Markov model (HMM) classifier [54]. The classifier was trained with sets of 500 FFRs per tone category. The remaining FFRs (500 per tone category) were used for testing. Training and testing sets were smoothed with a moving average of 200 FFRs. This combination of training, testing and averaging sizes provides optimal decoding of tone categories (and robust cross-language differences) in sets of 1000 FFRs [54]. The performance of the classifier was K-fold cross-validated. HMM, accuracy for each tone was computed from the cross-validated confusion matrix as the number of true positives and negatives over the number of true and false positives and negatives.

Behavioral Statistical Analyses

Linear mixed-effects regression (LMER) analyses were implemented on all behavioral variables to examine effects of training on behavioral performance (accuracy and median reaction time) in English learners, relative to native Mandarin performance. The native Mandarin performance was considered training criterion for reaching an expert level of speech categorization performance. Analyses were carried out in R, an open source programming language for statistical computing (R Development Core Team, 2014). We used the lme4 package [73] and computed p-values using the Satterthwaite's approximation for denominator degrees of freedom with the lmerTest package [74]. For all LMER models, we included one fixed-effect factor: training level (native, novice, experienced, over-trained, retention), with the performance of native Mandarin participants as the reference level. We additionally conducted an LMER analysis to investigate the interaction between training level (native, novice, over-trained, experienced, and retention) and tone token (1–7) on mean perceptual identification reaction time. In this analysis, the reference levels were native Mandarin performance and tone token 4, since native Mandarin performance was considered training criterion for other metrics, and tone token 4 is the categorical boundary of the tone continuum. The results of this analysis are reported in Table S1. All LMER models included by-participant random intercepts to account for inter-subject variability. All behavioral results reported are from a single model that included all training levels.

EEG Statistical Analyses

A two-way repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to examine the effect of sound-to-category training on the neural tracking of Mandarin lexical tone F0 contours. In this analysis, learning phase (novice, experienced, over-trained, and retention) and stimulus (Tone 1, Tone 2, Tone 3, Tone 4) were included as within-subject factors. We examined two neural tracking metrics that have consistently demonstrated language experience-dependent plasticity, as well as training-induced plasticity: peak autocorrelation and stimulus-to-response correlation (for further details of metrics see:[21]). We report Greenhouse-Geisser corrected results for all ANOVA analyses.

Data and Software Availability

Our behavioral and EEG data are available to download via Mendeley Data at http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/j2z2km4p9y.2 and http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/cvjjs4vdww.2, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Adults are trained to perceptually master a difficult non-native phonetic contrast

Sensory and perceptual plasticity emerge at different timescales

Training modifies sensory encoding at a slower timescale relative to perception

Perceptual and sensory gains are retained beyond the cessation of training

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute On Deafness and Other Communication Disorders of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R01DC015504 (BC) and R01DC013315 (BC). Earlier stages of this project were presented as podium presentations at the 2016 and 2017 Mid-Winter meetings of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology, where we received helpful feedback from peers. The authors would like to thank Jessica Roeder for the development of the dual-task, and Erika Skoe for providing the Matlab codes to create the autocorrelograms and implement the F0 tracking analysis. We also thank the members of the SoundBrain Laboratory for assistance with participant recruitment, data collection, and data preprocessing. Finally, the authors would like to thank three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.C. and R.R.; Methodology, R.R., Z.X. and B.C.; Formal Analysis, R.R., Z.X. and F.L.; Investigation, R.R. and Z.X.; Resources, B.C.; Data Curation, R.R., Z.X., and F.L.; Writing – Original Draft, R.R. and B.C.; Writing – Review & Editing, R.R., Z.X., F.L., and B.C.; Visualization, R.R., Z.X., and F.L.; Project Administration, R.R. and B.C.; Funding Acquisition, B.C.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Zhang Y, Kuhl PK, Imada T, Iverson P, Pruitt J, Stevens EB, Kawakatsu M, Tohkura Yi, Nemoto I. Neural signatures of phonetic learning in adulthood: a magnetoencephalography study. Neuroimage. 2009;46:226–240. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong PC, Perrachione TK. Learning pitch patterns in lexical identification by native English-speaking adults. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2007;28:565–585. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Werker JF, Hensch TK. Critical periods in speech perception: new directions. Annual Review of Psychology. 2015;66 doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuhl PK, Tsao FM, Liu HM. Foreign-language experience in infancy: Effects of short-term exposure and social interaction on phonetic learning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100:9096–9101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1532872100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song JH, Skoe E, Wong PC, Kraus N. Plasticity in the adult human auditory brainstem following short-term linguistic training. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2008;20:1892–1902. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gold J, Bennett P, Sekuler A. Signal but not noise changes with perceptual learning. Nature. 1999;402:176. doi: 10.1038/46027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jurjut O, Georgieva P, Busse L, Katzner S. Learning enhances sensory processing in mouse V1 before improving behavior. Journal of Neuroscience. 2017:3485–3416. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3485-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahissar M, Nahum M, Nelken I, Hochstein S. Reverse hierarchies and sensory learning. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 2009;364:285–299. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hochstein S, Ahissar M. View from the top: Hierarchies and reverse hierarchies in the visual system. Neuron. 2002;36:791–804. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yi HG, Maddox WT, Mumford JA, Chandrasekaran B. The Role of Corticostriatal Systems in Speech Category Learning. Cerebral Cortex. 2016;26:1409–1420. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhu236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fahle M. Perceptual learning: specificity versus generalization. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2005;15:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skoe E, Kraus N. Auditory brainstem response to complex sounds: a tutorial. Ear and hearing. 2010;31:302. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181cdb272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coffey EB, Herholz SC, Chepesiuk AM, Baillet S, Zatorre RJ. Cortical contributions to the auditory frequency-following response revealed by MEG. Nature Communications. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kraus N, White-Schwoch T. Unraveling the Biology of Auditory Learning: A Cognitive–Sensorimotor–Reward Framework. Trends in cognitive sciences. 2015;19:642–654. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2015.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hélie S, Waldschmidt JG, Ashby FG. Automaticity in rule-based and information-integration categorization. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics. 2010;72:1013–1031. doi: 10.3758/APP.72.4.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helie S, Roeder JL, Ashby FG. Evidence for cortical automaticity in rule-based categorization. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30:14225–14234. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2393-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ashby FG, Ennis JM, Spiering BJ. A neurobiological theory of automaticity in perceptual categorization. Psychological review. 2007;114:632. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.114.3.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carcagno S, Plack CJ. Subcortical plasticity following perceptual learning in a pitch discrimination task. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology. 2011;12:89–100. doi: 10.1007/s10162-010-0236-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong PC, Skoe E, Russo NM, Dees T, Kraus N. Musical experience shapes human brainstem encoding of linguistic pitch patterns. Nature neuroscience. 2007;10:420–422. doi: 10.1038/nn1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tierney AT, Krizman J, Kraus N. Music training alters the course of adolescent auditory development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015;112:10062–10067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505114112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie Z, Reetzke R, Chandrasekaran B. Stability and plasticity in neural encoding of linguistically relevant pitch patterns. Journal of neurophysiology. 2017;117:1407–1422. doi: 10.1152/jn.00445.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watanabe T, Náñez JE, Koyama S, Mukai I, Liederman J, Sasaki Y. Greater plasticity in lower-level than higher-level visual motion processing in a passive perceptual learning task. Nature neuroscience. 2002;5:1003–1009. doi: 10.1038/nn915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shamma S. On the emergence and awareness of auditory objects. PLoS biology. 2008;6:e155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahissar M, Hochstein S. The reverse hierarchy theory of visual perceptual learning. Trends in cognitive sciences. 2004;8:457–464. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fritz JB, David S, Shamma S. Neural correlates of auditory cognition. Springer; 2013. Attention and dynamic, task-related receptive field plasticity in adult auditory cortex; pp. 251–291. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fritz JB, David SV, Radtke-Schuller S, Yin P, Shamma SA. Adaptive, behaviorally gated, persistent encoding of task-relevant auditory information in ferret frontal cortex. Nature neuroscience. 2010;13:1011–1019. doi: 10.1038/nn.2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atiani S, David SV, Elgueda D, Locastro M, Radtke-Schuller S, Shamma SA, Fritz JB. Emergent selectivity for task-relevant stimuli in higher-order auditory cortex. Neuron. 2014;82:486–499. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.David SV, Fritz JB, Shamma SA. Task reward structure shapes rapid receptive field plasticity in auditory cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:2144–2149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117717109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Polley DB, Steinberg EE, Merzenich MM. Perceptual learning directs auditory cortical map reorganization through top-down influences. Journal of neuroscience. 2006;26:4970–4982. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3771-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caras ML, Sanes DH. Top-down modulation of sensory cortex gates perceptual learning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2017 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1712305114. 201712305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldstone RL. Perceptual learning. Annual review of psychology. 1998;49:585–612. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skoe E, Chandrasekaran B, Spitzer ER, Wong PC, Kraus N. Human brainstem plasticity: the interaction of stimulus probability and auditory learning. Neurobiology of learning and memory. 2014;109:82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chandrasekaran B, Kraus N, Wong PC. Human inferior colliculus activity relates to individual differences in spoken language learning. Journal of neurophysiology. 2012;107:1325–1336. doi: 10.1152/jn.00923.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lively SE, Logan JS, Pisoni DB. Training Japanese listeners to identify English/r/and/l/. II: The role of phonetic environment and talker variability in learning new perceptual categories. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1993;94:1242–1255. doi: 10.1121/1.408177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bradlow AR, Akahane-Yamada R, Pisoni DB, Tohkura Yi. Training Japanese listeners to identify English/r/and/l: Long-term retention of learning in perception and production. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics. 1999;61:977–985. doi: 10.3758/bf03206911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roelfsema PR, van Ooyen A, Watanabe T. Perceptual learning rules based on reinforcers and attention. Trends in cognitive sciences. 2010;14:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fritz JB, Shamma S, Elhilali M, Klein D. Rapid task-related plasticity of spectrotemporal receptive fields in primary auditory cortex. Nature neuroscience. 2003;6 doi: 10.1038/nn1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weinberger NM, Javid R, Lepan B. Long-term retention of learning-induced receptive-field plasticity in the auditory cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1993;90:2394–2398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Slee SJ, David SV. Rapid task-related plasticity of spectrotemporal receptive fields in the auditory midbrain. Journal of Neuroscience. 2015;35:13090–13102. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1671-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weinberger NM. Specific long-term memory traces in primary auditory cortex. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2004;5:279–290. doi: 10.1038/nrn1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bao S, Chan VT, Merzenich MM. Cortical remodelling induced by activity of ventral tegmental dopamine neurons. Nature. 2001;412:79–83. doi: 10.1038/35083586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Galván VV, Weinberger NM. Long-term consolidation and retention of learning-induced tuning plasticity in the auditory cortex of the guinea pig. Neurobiology of learning and memory. 2002;77:78–108. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2001.4044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reed A, Riley J, Carraway R, Carrasco A, Perez C, Jakkamsetti V, Kilgard MP. Cortical map plasticity improves learning but is not necessary for improved performance. Neuron. 2011;70:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Molina-Luna K, Hertler B, Buitrago MM, Luft AR. Motor learning transiently changes cortical somatotopy. Neuroimage. 2008;40:1748–1754. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wenger E, Brozzoli C, Lindenberger U, Lövdén M. Expansion and Renormalization of Human Brain Structure During Skill Acquisition. Trends in cognitive sciences. 2017;21:930–939. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2017.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fu M, Zuo Y. Experience-dependent structural plasticity in the cortex. Trends in neurosciences. 2011;34:177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holtmaat A, Svoboda K. Experience-dependent structural synaptic plasticity in the mammalian brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2009;10:647–658. doi: 10.1038/nrn2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Suga N. Tuning shifts of the auditory system by corticocortical and corticofugal projections and conditioning. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2012;36:969–988. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suga N, Xiao Z, Ma X, Ji W. Plasticity and corticofugal modulation for hearing in adult animals. Neuron. 2002;36:9–18. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00933-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krishnan A, Gandour JT, Bidelman GM. Brainstem pitch representation in native speakers of Mandarin is less susceptible to degradation of stimulus temporal regularity. Brain Research. 2010;1313:124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.11.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pisoni DB, Tash J. Reaction times to comparisons within and across phonetic categories. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics. 1974;15:285–290. doi: 10.3758/bf03213946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hallé PA, Chang YC, Best CT. Identification and discrimination of Mandarin Chinese tones by Mandarin Chinese vs. French listeners. Journal of phonetics. 2004;32:395–421. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bidelman GM, Lee CC. Effects of language experience and stimulus context on the neural organization and categorical perception of speech. Neuroimage. 2015;120:191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.06.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Llanos F, Xie Z, Chandrasekaran B. Hidden Markov modeling of frequencyfollowing responses to Mandarin lexical tones. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2017;291:101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bidelman GM, Gandour JT, Krishnan A. Cross-domain effects of music and language experience on the representation of pitch in the human auditory brainstem. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2011;23:425–434. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schön D, Magne C, Besson M. The music of speech: Music training facilitates pitch processing in both music and language. Psychophysiology. 2004;41:341–349. doi: 10.1111/1469-8986.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chandrasekaran B, Yi HG, Maddox WT. Dual-learning systems during speech category learning. Psychonomic bulletin & review. 2014;21:488–495. doi: 10.3758/s13423-013-0501-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shiffrin RM, Schneider W. Controlled and automatic human information processing: II. Perceptual learning, automatic attending and a general theory. Psychological review. 1977;84:127. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xu Y, Gandour JT, Francis AL. Effects of language experience and stimulus complexity on the categorical perception of pitch direction. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2006;120:1063–1074. doi: 10.1121/1.2213572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Skoe E, Krizman J, Spitzer E, Kraus N. The auditory brainstem is a barometer of rapid auditory learning. Neuroscience. 2013;243:104–114. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Russo N, Nicol T, Musacchia G, Kraus N. Brainstem responses to speech syllables. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2004;115:2021–2030. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chandrasekaran B, Kraus N. The scalp-recorded brainstem response to speech: Neural origins and plasticity. Psychophysiology. 2010;47:236–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2009.00928.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Skoe E, Krizman J, Anderson S, Kraus N. Stability and plasticity of auditory brainstem function across the lifespan. Cerebral Cortex. 2015;25:1415–1426. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bidelman GM, Pousson M, Dugas C, Fehrenbach A. Test–Retest Reliability of Dual-Recorded Brainstem versus Cortical Auditory-Evoked Potentials to Speech. 2017 doi: 10.3766/jaaa.16167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krishnan A, Xu Y, Gandour J, Cariani P. Encoding of pitch in the human brainstem is sensitive to language experience. Cognitive Brain Research. 2005;25:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Krishnan A, Gandour JT, Bidelman GM. Experience-dependent plasticity in pitch encoding: from brainstem to auditory cortex. Neuroreport. 2012;23:498. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328353764d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Krishnan A, Xu Y, Gandour JT, Cariani PA. Human frequency-following response: representation of pitch contours in Chinese tones. Hearing research. 2004;189:1–12. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(03)00402-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schneider W, Eschman A, Zuccolotto A. E-Prime: User's guide. Psychology Software Incorporated; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Huang W-T, Liu C, Dong Q, Nan Y. Categorical perception of lexical tones in mandarin-speaking congenital amusics. Frontiers in psychology. 2015;6 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Elzhov TV, Mullen KM, Bolker B. minpack. lm: R Interface to the Levenberg- Marquardt Nonlinear Least-Squares Algorithm Found in MINPACK. 2009 R package version, 1.1–1. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Marquardt DW. An algorithm for least-squares estimation of nonlinear parameters. Journal of the society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. 1963;11:431–441. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Boersma P. Accurate short-term analysis of the fundamental frequency and the harmonics-to-noise ratio of a sampled sound. Proceedings of the institute of phonetic sciences; Amsterdam. 1993. pp. 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using Eigen and S4. R package version. 2014;1:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, Christensen RHB. R package version 2. 2015. Package ‘lmerTest’. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.