Abstract

Hydrogen photoproduction from microalgae has been an emerging topic for biofuel development. However, low yield for large-scale cultivations seems to be the main challenge. Immobilization seems to be an alternative method for sustainable hydrogen generation. In this study we examined the bead stability, bead diameter and immobilization method in accordance with photobioreactors (PBR). 2.1 mm diameter beads were selected for PBR experiments. CSTR, tubular and panel type PBRs give important results to develop suitable immobilization matrixes and techniques for mass production in scalable PBR systems. In conclusion, we suggest to develop techniques specific for the design and operation characteristic of the PBR for a yield efficient hydrogen generation.

Keywords: Alginate, Biohydrogen, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, Immobilization, Microalgae, Photobioreactor

Introduction

Among conventional hydrogen production technologies, biohydrogen and specifically microalgal biohydrogen production has been considered as a promising source to fuel up hydrogen energy development via photosynthesis (Rupprecht 2009) Biohydrogen production process is highly dependent on metabolic pathways and sensitive to various culture conditions as well as intracellular interactions (Melis et al. 2000; Eroglu and Melis 2016). A well-defined approach to produce hydrogen is the temporal separation of aerobic and anaerobic phases, by providing sulfur-depleted media conditions to down regulate D1 protein synthesis (Wykoff et al. 1998; Kosourov and Seibert 2009; Eroglu and Melis 2016). Although this method helped numerous studies to reveal the underlying mechanism of biohydrogen production from microalgae, the challenges still exist for scale up to a larger volume to reach commercial scale.

Cell suspension cultures are sensitive to changing environmental conditions like O2 existence, illumination, agitation, temperature and pH (Kumar et al. 2016). To overcome these limits, immobilization as an alternative method seems to be promising for sustainability and prolongation of production in anaerobic environmental conditions (Antal et al. 2016). In an immobilized system, tolerance to external stress factors is increased, higher cell density can be obtained, hydrogen production can be prolonged and a shorter time is required for PSII activity to drop below respiration (Antal et al. 2014). With regard to the basics of immobilization; cells are separated from the liquid culture medium via a solid support matrix (Laurinavichene et al. 2006). Alginate as a polymerization matrix is preferred in most of the cases due to its nontoxic nature, efficient mass transfer characteristics, transparency to allow light to penetrate and reach the microalgae cells (Touloupakis et al. 2016).

Meanwhile, another concern fpr photbiohydrogen production is the desıgn and operation of photobioreactor (PBR) systems. PBR design and operation is a major challenge for larger scales to prevent leakage, sustain microalgal metabolism and optimum parameters in an efficient way (Oncel and Kose 2014; Skjånes et al. 2016). A novel understanding should be adapted to produce hydrogen with high volumetric efficiency in smaller scales. Immobilized beads or fibers can efficiently maintain denser culture with a higher surface-to-volume ratio in smaller scales of PBRs where immobilization technique provides easier operational conditions for PBRs due to the less space requirements in comparison with suspension cultures (Tsygankov et al. 1994; Kosourov et al. 2014). Immobilization is a relatively new technique for microalgal biohydrogen production; thus research in this field is emerging for novel developments.

Within this context the aim of this study was the investigation of immobilization concept for photobiohydrogen production by using Chlamydomonas reinhardtii strain CC124 with a special emphasis on PBR types. The study comprises the selection of optimum immobilization technique and bead size to provide higher cell viability, bead stability in PBR production and hydrogen production in comparison with conventional PBR types.

Materials and methods

Stock culture growth and maintenance

Axenic cultures of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii strain CC124 were cultivated photoheterotrophically for biohydrogen production experiments. The stock cultures in 5 mL of tris acetate phosphate (TAP) agar slants were kept under constant irradiation (40 µE m−2 s−1) provided by cool white fluorescent lamps (Phillips, Netherlands) at 27 ± 0.5 °C. Cells in agar slants were activated in 5 mL of liquid culture medium for 3–5 days until a visible color change to green was observed and step-wisely transferred to 25 and 150 mL of Erlenmeyer shake flasks with a shaking frequency of 105 rpm (Zhicheng, CHINA), 40 µE m−2 s−1, 27 ± 0.5 °C (Oncel and Vardar-Sukan 2009). The stock cultures were maintained by weekly dilutions of discharging of 50 mL of culture and replacing 50 mL of TAP medium. The initial chlorophyll amounts of diluted cultures were kept 8 ± 1 mg L−1.

Culture growth for aerobic phase

Stock cultures at mid logarithmic growth phase, cultivated in 1 L culture flasks, were used as inoculum for the immobilization experiments with an initial chlorophyll amount of 4 ± 1 mg L−1. Inoculum cultures, stirred with magnetic bars, were cultivated under constant illumination (70 µE m−2 s−1) and fed with CO2 enriched air (3% v/v).

Biohydrogen production phase (anaerobic growth)

The cell suspension cultures reaching a chlorophyll amount of 24 ± 2 mg L−1 were immobilized according to the selected method and bead size (see Immobilization procedures). The immobilized cultures were transferred to the PBRs. The PBRs were well sealed to provide anaerobic conditions. Gas exhaust port was connected to calibrated water columns for the measurement of hydrogen gas production volumetrically. Biohydrogen production was followed on daily basis until the hydrogen gas generation is ceased.

Immobilization procedures

Sodium alginate (Merck, GERMANY) was utilized as the immobilization matrix (4% g mL−1 concentration in water) and CaCl2 (20 g L−1) was used as polymerization agent. The beads were generated in laminar air flow cabinet to provide aseptic conditions. Na-Alginate was mixed with the wet biomass in a volume (mL) ratio of 1:4 (Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: Na-Alginate) and gently agitated to distribute cells into the alginate solution homogenously. Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: Na-Alginate mixture was dropped to a sterile CaCl2 solution and left to harden for 30 min at room temperature. CaCl2 solution was gently stirred with magnetic bars to prevent bead aggregation. After 30 min, beads were washed and transferred to the anaerobic culture conditions according to the methods described in Table 1. After the selection of optimum immobilization procedure, the bead diameter was determined. For this purpose various tips with different diameters were used. The bead size determination experiments were done in 100 mL flasks gently stirred with magnetic bars corresponding to 50 ± 10 rpm.

Table 1.

Immobilization methods to determine optimum procedure

| Method code | Aerobic phase culture growth | Anaerobic hydrogen production phase | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Washing | Solid phase | Mobile phase | ||

| i | Immobilizeda | TAP-S | TAP | TAP-S |

| ii | Immobilizedb | TAP-S | Distilled water | TAP-S |

| iii | Suspensionc | TAP-S | TAP-S | TAP-S |

| iv | Suspension | TAP-S | Distilled water | TAP-S |

| v | Suspension | Distilled water | TAP-S | Distilled water |

| vi | Suspension | TAP-S | TAP | TAP-S |

aChlamydomonas reinhardtii strain CC124 cultures with a 4 ± 0.5 mg L−1 chlorophyll amount is immobilized with TAP medium and cultivated in TAP medium. Beads reaching transfer chlorophyll amount are washed with TAP-S medium and anaerobic phase hydrogen production is done in TAP-S medium as mobile phase

bChlamydomonas reinhardtii strain CC124 cultures with a 4 ± 0.5 mg L−1 chlorophyll amount is immobilized with distilled water and cultivated in TAP medium. Beads reaching transfer chlorophyll amount are washed with TAP-S medium and anaerobic phase hydrogen production is done in TAP-S medium as mobile phase

cSuspension cultures reaching 24 ± 2 mg L−1 chlorophyll amount are harvested and immobilized according to the method codes of iii, iv, v, vi

PBR experiments

Selected immobilization method and bead size were utilized for further PBR experiments. PBRs with a working volume of 5 L were investigated to see the effects of in PBRs for biohydrogen production (Oncel and Kose 2014). The immobilized beads were inoculated into the PBRs, sealed and connected to the calibrated water columns. Hydrogen generation was checked on daily basis; beads were collected in order to measure cell viability and chlorophyll amount.

Analytical procedures

Light intensity was measured via light meter with a quantum sensor (Licor, Lincoln, USA, Li-250A). Cell density, PSII activity and chlorophyll fluorescence were measured as previously described (Oncel and Vardar-Sukan 2009; Oncel and Kose 2014). GF/C membranes were kept at 55 °C for another 24 h and weighted (Ohaus, Switzerland). Biohydrogen production was monitored with the voltage difference by the utilization of PEM fuel cells. All the analysis was done in triplicate.

Results and discussion

Selection of the immobilization method

Prior to any experiments, the immobilization method was selected. It is aimed to demonstrate a reliable method further to be utilized for the immobilization of microalgae cells. Preliminary studies were done to understand the ability of C. reinhardtii cells to maintain cellular functions in a solid and entrapped area. For this purpose six different approaches were examined to immobilize C. reinhardtii cells into alginate beads and choose the best fitting method to maintain bead stability and cell viability (Table 1). The transparency of the selected solid matrix agent is crucial for microalgae experiments, because C. reinhardtii cells are light-dependent hydrogen producers. For this purpose alginic acid was chosen due to high light penetration efficiency. The chlorophyll fluorescence was measured to determine cellular activity and viability along with the chlorophyll amount. At initial experiments, the alginic acid solution was prepared in TAP or TAP-S medium according to the experiments presented in Table 1. However, the beads prepared in TAP or TAP-S medium dissolved rapidly due to the phosphate in the medium. As a result, alginic acid solution was prepared with dH2O in all the experiments. Following experiments were done to decide the mobile phase (the cultivation medium) and the solid phase (bead interior) composition. Another aim of experimenting on various immobilization methods was to decide the cell growth phase. This was done because a certain amount of biomass is required to shift from aerobiosis to anaerobiosis in order to trigger hydrogen photoproduction (Ghirardi et al. 2000). Rather than measuring biomass, the chlorophyll content was utilized as an indicator to transfer culture to anaerobic state as it is regularly done with suspension cultures (Oncel and Kose 2014).

The aerobic growth phase experiments were done using both suspended and immobilized cells which had initial chlorophyll content of 24 ± 2 and 4 ± 0.5 mg L−1, respectively. The experiments coded as i and ii were immobilized at culture growth phase with an initial cell number of 2 ± 0.5 × 104 cells mL−1. However, the experiments i, ii showed no measurable amounts of cell survival. Within 48 h the cells in the beads were bleached and no living cells were determined in the beads. The mobile phase also did not contain any cells as well. Even cells incubated in S-replete TAP medium yet could not maintain cell growth. This was considered to be a result of photoinhibiton of dilute cells in the alginate beads accompanied with the mass transfer limitations. The alginate coating around the cells is thicker and in an entrapped area cells lack the place to grow and reproduce. The initial hypothesis is also in a good accordance with this, but starting with immobilized aerobic phase experiments, it was aimed to cycle aerobic and anaerobic cells in beads to skip cell growth phase in suspension cultures. Insignificant cell viability and loss of initial cultures indicated that to start immobilization experiments, a denser cell culture is required. According to the obtained results from immobilized aerobic growth phase experiments, cells were cultivated in suspension cultures to reach a 24 ± 2 mg mL−1 chlorophyll amount at the mid-logarithmic growth phase of the culture, corresponding to 74 ± 2 h and a chlorophyll fluorescence of 0.73 ± 0.05. The immobilization experiments were done after harvesting the biomass obtained from aerobic suspension culture growth. The results obtained from selection of immobilization method are given in Table 2. Washing the harvested biomass with TAP-S or dH2O did not affect the bead stability or cellular survival. Both the washing solutions were enough to purge residual sulfur. The significant change was observed with the changing solid and mobile phase solutions. Trapping cells with TAP-S and using dH2O as a mobile phase did not support cell growth and cellular viability (experiment v). TAP-S medium components in the alginate beads kept cells alive for 72 ± 4 h; however, no measurable amount of hydrogen production was observed. The experiments coded as vi were done as solid phase TAP and mobile phase TAP-S medium. Cells maintained their viability: even after 10 days no hydrogen production was observed. It is thought to be that TAP and TAP-S medium is sufficient enough to keep cellular metabolism alive providing nutrients for cellular activity; however, due to the sulfur components in the TAP medium cells cannot produce hydrogen. Even if anaerobiosis was provided in the sealed cultivation units, existing TAP medium (having sulfur components inside) can still block hydrogenase enzyme activation due to the continuous PSII repair via D1 protein (which has subunit amino acids containing sulfur).

Table 2.

Results from immobilization procedures

| Experiment codes | i | ii | iii | iv | v | vi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (days) | 2 ± 0.5 | 2 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 10 ± 1 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 10 ± 0.5 |

| Hydrogen generation | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| PSII measurement | − | − | + | − | − | + |

| Cell leakage | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| Chlorophyll determination | − | − | + | − | − | + |

| Cell survival | − | − | + | − | − | + |

“+” refers to occurrence of the events in first column and “−”refers opposite

The experiment codes for iv and v were poor in the stability and cellular viability. After 24 h of the immobilization, the anaerobic cultures lost their representing green color. This occurrence was not the expected result. As far as known from suspended cells, microalgae cells starts to lose color and viability after 4–5 days of anaerobic cultivation (Melis et al. 2000; Melis 2002). For those experiments, C. reinhardtii cells are found in the mobile phase. Due to quick cell loss, the experiments were not successful enough to produce biohydrogen. The chlorophyll amount of the cells in the beads could not be determined as well.

The measurable biohydrogen production could only be achieved with iii. In this experiment cells were washed with TAP-S; mobile and solid phase was also prepared with TAP-S. The culture was monitored for 12 days in terms of hydrogen evolution, bead stability, photosynthetic activity and cell viability (Fig. 1). The results indicate that at the edge of anaerobiosis residuel oxygen and sulfur is the main reason for the delay of the metabolism shift from aerobiosis to anaerobiosis. Thus TAP-S as a mobile phase was required in order to maintain nutrients for anaerobic cell survival keeping sulfur as limited substrate (Laurinavichene et al. 2008; Vargas et al. 2016). With these results, the experiments were continued to determine bead size for further experiments.

Fig. 1.

H2 photoproduction at immobilization method coded iii

Determination of the bead size, cell viability and hydrogen production

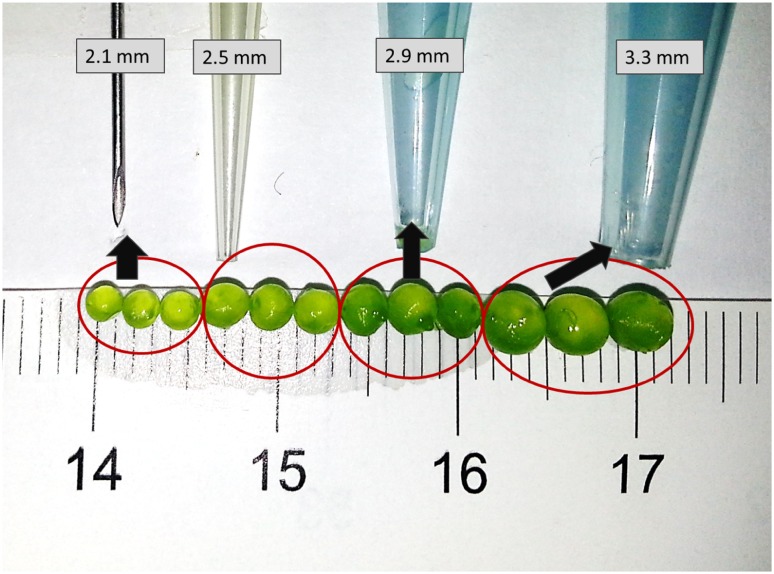

Mechanical stability of the alginate beads are known to be weak in bioreactor systems. Thus it was aimed to find the optimal bead size with stable hydrogen production, cell viability and also protection of the existing bead morphology. Four various tips were tried to form alginic acid + C. reinhardtii cells droplets into CaCl2 solution (Fig. 2). The gentle agitation helped beads to homogenously mix and avoid bead contact thus providing an environment to obtain spherical beads. With varying tip diameter, bead diameters were 2.1 ± 0.11; 2.5 ± 0.2; 2.9 ± 0.3 and 3.3 ± 0.3 mm, respectively. The cultures were monitored for 10 days until the hydrogen production ceased. To compare with the suspension culture, a control set with suspended free living C. reinhardtii cell was added. Initial chlorophyll amount of the suspension culture was 12 ± 0.3 mg mL−1 in the beads. The chlorophyll fluorescence of both suspension and immobilized cultures was 0.69 ± 0.05. To avoid fluctuations resulting from different cell cultures, the same inoculation culture was utilized for all the bead size determination experiments. The beads were bleached at the earlier stages of the anaerobic experiments. The Chlorophyll amount in the alginate beads was a significant criterion representing cell loss, bead stability and fluorescence activity as well as hydrogen production. Thus initial chlorophyll amount was increased to24 ± 2 mg mL−1. Beads with 24 ± 2 mg mL−1 chlorophyll retained their activity for at least 40 days.

Fig. 2.

The bead sizes and immobilization tip diameters (mm) representing the study for the selection of optimum bead size to sustain cell survival and prolonged biohydrogen production

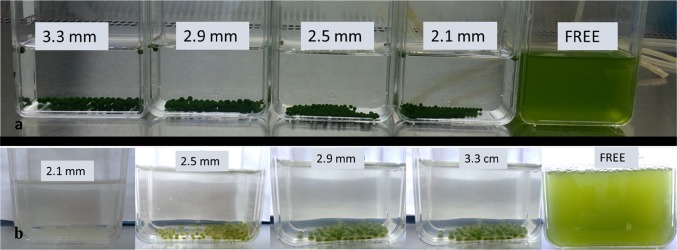

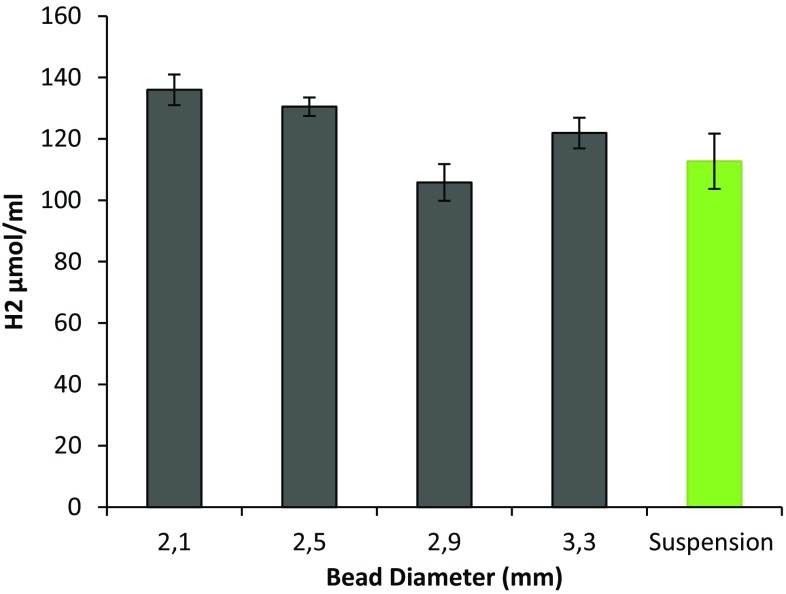

Figure 3 represented the initial (a) and final (b) of the hydrogen production. The hydrogen photoproduction was monitored for 10 days (Fig. 2). The beads with a diameter of 2.1 ± 0.1 mm were bleached to a color that no visible cells were observed. The mobile phase did not contain any cell leakages. However, in suspension cultures the final chlorophyll amount was 6.8 ± 0.2 mg mL−1. The final chlorophyll fluorescence was 0.05 ± 0.01 for free living cells; however it could not be determined for immobilized cells. The 2.1 mm beads showed slightly higher H2 generation (Fig. 4). Also considering the tubular PBR experiments, 2.1 mm was selected for further experiments. If the hydrogen photoproduction was the only criteria for the selection, these four tips may be accurate for further experiments; however, considering light penetration efficiency and mass transfer limitation, the smaller globular structure of the beads are an advantage. When the bead volume and size are decreased a larger surface/volume area is obtained. This results in a more homogeneous distribution in the PBR leading to an efficient use of light resulting in a better H2 photoproduction.

Fig. 3.

The biohydrogen production experiments controlling bead stability and cell viability in 100 mL culture vessel. The picture a is representing the biohydrogen production day 0; picture b is representing 10 days of the culture when biohydrogen production is finalized

Fig. 4.

H2 photoproduction in relation with bead diameter

The effect of PBR design on immobilized biohydrogen production

PBRs provide controlled environment and anaerobic conditions for biohydrogen studies (Berberoglu et al. 2007; Oncel and Sukan 2008). Yet to date biohydrogen production in PBRs has been demonstrated with cell suspension cultures. This study evaluates the utilization, advantages and disadvantages of PBRs with immobilized microalgae for biohydrogen generation for the first time. Three different classical types of PBRs, panel, tubular and CSTR were used for the experiments. The operational parameters of the PBRs are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Operational parameters of PBRs

| Tubular | Panel | CSTR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mixing strategy | Peristaltic pumping | Mechanical impeller; 2 × 6 blade Rushton Turbine propeller | Mechanical impeller; 3 × 6 blade Rushton Turbine propeller |

| Mixing time (min) | 2 ± 0.5 min to keep beads homogenous | ||

| Illumination (µE m−2 s−1) | Tube side = 150 Tank side = 400 |

70 × 2 faces = 140 | 70 × 2 faces = 140 |

| Area/volume (A/V) | Tube side = 112.5 m−1 (illuminated area: 0.45 m2; volume: 0.005 m3) Tank side = 50 m−1 (illuminated area: 0.5 m2; volume: 0.001 m3) |

34 m−1 (illuminated area: 0.17 m2; volume: 0.005 m3) | 28 m−1 (illuminated area: 0.14 m2; volume: 0.005 m3) |

| Temperature (°C) | 27 ± 0.5 | 27 ± 0.5 | 27 ± 0.5 |

Even though immobilization have several advantages, in PBR systems where the mechanical forces can be effective, the key is to sustain the balance between the bead stability and homogenous mixing conditions (Dainty et al. 1986). Table 4 represents the H2 production results for PBR experiments. We evaluated the experiments in 5 L of PBRs of each type, supplemented with equal light intensity. However, due to the design and operation criteria the survey of the immobilized algal cells differs. The mixing strategy for each design is different; in panel and CSTR types 6-bladed Rushton turbine type mechanical mixers were used. However in tubular type PBR, mixing was only provided via the pumping effect which regulates the fluid flow in the tubes. The early observations on the PBRs showed that biohydrogen production with immobilized culture requires some additional attention.

Table 4.

Hydrogen photoproduction data from various types of PBRs

| PBR type | Total cultivation time (day) | Lag Phase (h) | Column hydrogen production duration (day) | Head space volume (mL) | H2 production in the column (mL) | Total Hydrogen (ml L−1) | Productivity (mL L−1 day−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel | 11 | 72 ± 3 | 8 | 1100 | 490 | 318 | 6.02 |

| CSTR | 10 | 80 ± 5 | 7.5 | 940 | 340 | 256 | 128 |

| Tubular | 8 | 144 ± 2 | 3 | 600 | 40 | 128 | 80 |

The very first problem is the low mechanical stability of the beads in the bioreactors. Beads are broken easily or deformed due to the mixing effect. In panel and CSTR the bead stability could be controlled with a decrease in the mechanical mixer speed (rpm); however, a certain decrease lowers the Reynolds number to a laminar flow and mixing time is prolonged. As a result beads are accumulated at the bottom of the PBRs. Aggregation at the PBR bottom limits the light penetration efficiency and hydrogen photoproduction ceased in an earlier stage of the culture (Kosourov et al. 2014). In tubular PBR, the mixing is provided with peristaltic pump. In order to circulate the fluids with the beads, beads also pass through the pump; as a time affect beads start to break down and cells are disrupted mechanically. Mechanical disruption of the beads leads to a heterogeneous solution in the culture mixed with stable beads, alginate fragments and leaked C. reinhardtii cells.

Another point to mention about PBR systems is the attention needed to provide the well-sealed leakage free environment to sustain anaerobic conditions. This is especially important in the PBRs like systems having numerous ports and connections all of which are potential leakage points (Dainty et al. 1986; Oncel 2013; Touloupakis et al. 2016). CSTR and panel types can provide efficient environment for anaerobic conditions; however, tubing and tube junctions in the tubular PBR are a challenge to observe a well-sealed conditions. In our experiments we observed that sustaining anaerobic conditions is a problem with tubular type PBR. Panel and CSTR types acquired anaerobiosis in a short time; however, due to the leakage problems tubular PBRs took a lot more time for cells to shift their metabolism, which results in the decrease of the overall efficiency.

In comparison with the previous findings using suspension cultures, the lag phase of the immobilized cells are increased due to the limitations in the mass transfer problems in the beads. Suspension cells show a lag phase approx. 24 h apart from the design differences (Oncel and Sabankay 2012; Oncel and Kose 2014). However, the hydrogen production efficiency is increased with respect to the changes in the PBR design. The results obtained from tubular PBR are controversial, but due to the operation challenges advantages of the immobilization could be hampered.

Conclusions

Biohydrogen production from microalgae has been a proof of concept for biofuel development. This study utilized the basic concepts of the immobilization techniques to evaluate the responses of the operation conditions of immobilized cells in terms of biohydrogen production via conventional PBRs commonly used for microalgal bioprocesses. The results showed that even if immobilization seems to be promising; progress to photobioreactor systems needs further understanding. In its classical form immobilization techniques in PBRs is challenging. Tubular bioreactor system designs should be modified for sustainable biohydrogen generation. Panel type PBR is more reliable for large-scale immobilized biohydrogen production. Considering the utilization of PBRs for biohydrogen generation the main problem is the leakage of the certain junction points of PBR, and this can be prevented via hydrogen production-specific PBRs rather than conventional PBR types. With some specific design improvements with a special emphasis on the light penetration efficiency and leakage safe construction, existing PBRs can be modified for biohydrogen production which will help for the future studies. Thus this study suggests that utilization of microalgae cells for PBR utilization needs design alterations.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Antal TK, et al. Pathways of hydrogen photoproduction by immobilized Chlamydomonas reinhardtii cells deprived of sulfur. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2014;39(32):18194–18203. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2014.08.135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antal TK, et al. Hydrogen photoproduction by immobilized S-deprived Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: effect of light intensity and spectrum, and initial medium pH. Algal Res. 2016;17:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2016.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berberoglu H, Yin J, Pilon L. Light transfer in bubble sparged photobioreactors for H2 production and CO2 mitigation. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2007;32(13):2273–2285. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2007.02.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dainty AL, et al. Stability of alginate-immobilized algal cells. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1986;28(2):210–216. doi: 10.1002/bit.260280210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eroglu E, Melis A. Microalgal hydrogen production research. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2016;41(30):12772–12798. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.05.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghirardi ML, et al. Microalgae: a green source of renewable H2. Trends Biotechnol. 2000;18(12):506–511. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(00)01511-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosourov SN, Seibert M. Hydrogen photoproduction by nutrient-deprived Chlamydomonas reinhardtii cells immobilized within thin alginate films under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2009;102(1):50–58. doi: 10.1002/bit.22050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosourov S, et al. Hydrogen photoproduction by immobilized N2-fixing cyanobacteria: understanding the role of the uptake hydrogenase in the long-term process. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80(18):5807–5817. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01776-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar G, et al. Recent insights into the cell immobilization technology applied for dark fermentative hydrogen production. Bioresour Technol. 2016;219:725–737. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2016.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurinavichene TV, et al. Demonstration of sustained hydrogen photoproduction by immobilized, sulfur-deprived Chlamydomonas reinhardtii cells. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2006;31(5):659–667. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2005.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laurinavichene TV, et al. Prolongation of H2 photoproduction by immobilized, sulfur-limited Chlamydomonas reinhardtii cultures. J Biotechnol. 2008;134(3):275–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melis A. Green alga hydrogen production: progress, challenges and prospects. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2002;27(11):1217–1228. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3199(02)00110-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Melis A, et al. Sustained photobiological hydrogen gas production upon reversible inactivation of oxygen evolution in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol. 2000;122(January):127–135. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.1.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oncel SS. Microalgae for a macroenergy world. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2013;26:241–264. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2013.05.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oncel S, Kose A. Comparison of tubular and panel type photobioreactors for biohydrogen production utilizing Chlamydomonas reinhardtii considering mixing time and light intensity. Bioresour Technol. 2014;151:265–270. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.10.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oncel S, Sabankay M. Microalgal biohydrogen production considering light energy and mixing time as the two key features for scale-up. Bioresour Technol. 2012;121:228–234. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.06.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oncel S, Sukan FV. Comparison of two different pneumatically mixed column photobioreactors for the cultivation of Artrospira platensis (Spirulina platensis) Bioresour Technol. 2008;99(11):4755–4760. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oncel S, Vardar-Sukan F. Photo-bioproduction of hydrogen by Chlamydomonas reinhardtii using a semi-continuous process regime. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2009;34(18):7592–7602. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2009.07.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rupprecht J. From systems biology to fuel—Chlamydomonas reinhardtii as a model for a systems biology approach to improve biohydrogen production. J Biotechnol. 2009;142(1):10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skjånes K, et al. Design and construction of a photobioreactor for hydrogen production, including status in the field. J Appl Phycol. 2016;1(1):1–19. doi: 10.1007/s10811-016-0789-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touloupakis E, et al. Hydrogen production by immobilized Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2016;41(34):15181–15186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.07.075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsygankov AA, et al. Photobioreactor with photosynthetic bacteria immobilized on porous glass for hydrogen photoproduction. J Ferment Bioeng. 1994;77(5):575–578. doi: 10.1016/0922-338X(94)90134-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas JVC, et al. Modeling microalgae derived hydrogen production enhancement via genetic modification. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2016;41(19):8101–8110. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2015.12.217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wykoff DD, et al. The regulation of photosynthetic electron transport during nutrient deprivation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol. 1998;117(1327):129–139. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.1.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]