Follicular lymphoma (FL) is an incurable B-cell malignancy characterized by advanced stage disease and a heterogeneous clinical course, with high-risk groups including those that transform to an aggressive lymphoma, or progress early (within 2 years) following treatment. Recent sequencing studies have established the diverse genomic landscape and the temporal clonal dynamics of FL [1–7]; however, our understanding of the degree of spatial or intra-tumor heterogeneity (ITH) that exists within an individual patient is limited. In contrast, multi-site profiling in solid organ malignancies has demonstrated profound ITH impacting mechanisms of drug resistance and compromising precision-medicine-based strategies to care [8]. In FL, the rise in trials adopting targeted therapies such as EZH2, PI3K, and BTK inhibitors reflects this paradigm shift in cancer care and with the development of biomarker-driven studies highlights the need to accurately define genomic alterations with clinical relevance. As most FL patients manifest disseminated tumor involvement, we sought to uncover the extent and clinical importance of spatial heterogeneity in FL by using a combination of whole-exome and targeted deep sequencing (Supplementary methods).

Our study cohort comprised nine patients (SP1–SP9) each with two spatially separated synchronous biopsies including two patients (SP3 and SP4) with spatial samples at two timepoints (FL and transformation), yielding a total of 22 tumor samples (Table S1). To improve the sensitivity for variant detection, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) was performed on cell suspensions where available (15 of 22 tumors) (Supplementary methods and Tables S2, S3). Exome sequencing of both the tumor and paired germline DNA was performed (median depth 131×) (Table S3) and we identified between 35 and 130 non-synonymous somatic variants (SNVs) per sample corresponding to 659 coding genes comprising missense (81%), indels (10%), nonsense (7%), and splice site (2%) changes (Tables S4, S5). We verified 195/198 (98%) SNVs using an orthogonal platform (Haloplex HS), with a high concordance of variant allele frequencies (VAFs) (r = 0.91) (Table S6). The tumor purity was predicted across samples using the mclust algorithm (Supplementary methods and Figure S1), demonstrating a mean purity of 92% in FACS-sorted samples and 66% in non-sorted samples.

Although the spatially separated tumors shared identical BCL2-IGH breakpoints, we observed variable degrees of ITH, with on average 82% (range 50–99%) of variants shared between sites. To quantify this heterogeneity, we calculated the Jaccard Similarity Coefficient (JSC) [9] for each patient, which represents the ratio of shared to total (shared and discordant) variants for two samples, with values closer to 1 representing greater similarity between samples. This demonstrated a range of JSCs with the highest JSC observed in SP3 (0.92) and the lowest in SP8 (JSC = 0.41) where a higher proportion of variants were confined to only one spatial biopsy (Fig. 1a, S2). Furthermore, the majority of our cases consisted of paired nodal/extra-nodal sites, and the extent of genetic heterogeneity may be more profound if additional nodal and extra-nodal sites of disease were profiled. The higher levels of genetic ITH in our study did not translate to a more adverse outcome nor was it associated with a specific clinical phenotype, although this can only be addressed with a larger series.

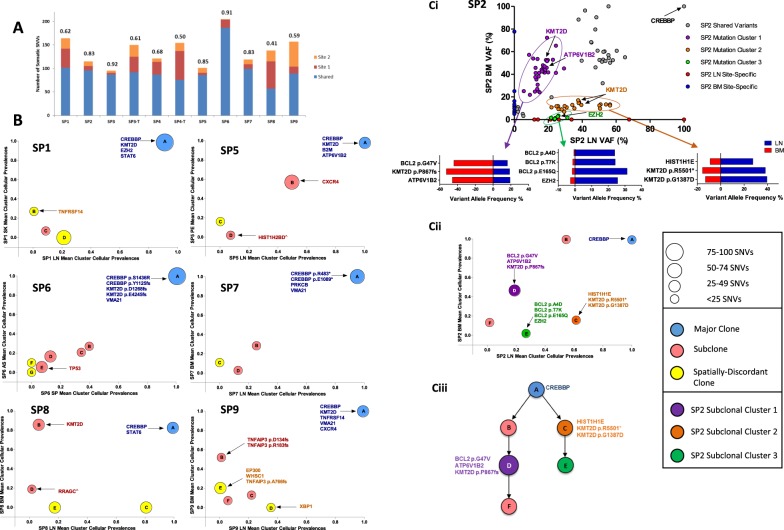

Fig. 1.

Patterns of intra-tumor heterogeneity in spatially separated tumors. a Proportion of shared and site-specific somatic SNVs in each case. The Jaccard Similarity Coefficient (JSC) is given above each bar. Site 1 is LN and site 2 BM with the following exceptions: SP1 site 2: skin (SK), SP4 site 1: LN1, site 2: LN2, SP4-T site 2: skin, SP5 site 2: pleural effusion (PE), SP6 site 1: ascites (AS), site 2: spleen (SP) (T: transformed). b Pairwise mean cluster cellular prevalence plots. Derived mutation clusters represent the mean cellular prevalence of all mutations within a cluster. Each cluster is denoted by a circle with the size of the circle equivalent to the number of mutations within the cluster. The letter in each circle relates to the specific cluster within the clonal phylogenies in Figure S3. Mutations in known FL-associated genes are highlighted to show their locations within clusters. ^Site-specific variant, although the mean cluster cellular prevalence is reported as marginally subclonal. c (i) Variant allele frequency (VAF) plot of all somatic mutations in case SP2. VAFs for selected mutations from three highlighted subclones in purple, orange, and green are shown in the horizontal bar graphs. c (ii) Mean cluster cellular prevalence plot and c (iii) clonal phylogeny of SP2 confirming the distinct subclones (purple, orange, green) seen in the VAF plot

To understand the clonal substructure of these spatially separated tumors, PyClone[16], a model-based clustering algorithm (Supplementary methods) was used to derive pairwise sub(clonal) clusters and reconstruct clonal phylogenies for each case (Fig. 1b, c and S3). This demonstrated tumors consisting of multiple subclones (mean 3, range 2–6), with the proportion of variants comprising the major clone (Fig. 1b) ranging from 6 to 68% (mean 40%). The non-linear distribution of subclones on the mean cluster cellular prevalence plots suggests differential subclonal dominance between spatial sites (Fig. 1b) and was best exemplified in SP2 where tumor cells from both compartments were FACS-purified. In this case, a variant cluster (Cluster 1) that included mutations in ATP6V1B2 (p.R400Q), BCL2 (p.G47V), and KMT2D (p.P867fs) were clonal in the bone marrow (BM) but subclonal in the lymph node, whereas the reverse was true for Cluster 2, consisting of mutations in KMT2D (p.G1387D and p.R5501*). We could also resolve a third cluster, including an EZH2 mutation (p.Y646S), with corrected VAFs ranging from 21 to 31% in the lymh node (LN) and 0.6–2.6% in the BM (Fig. 1c).

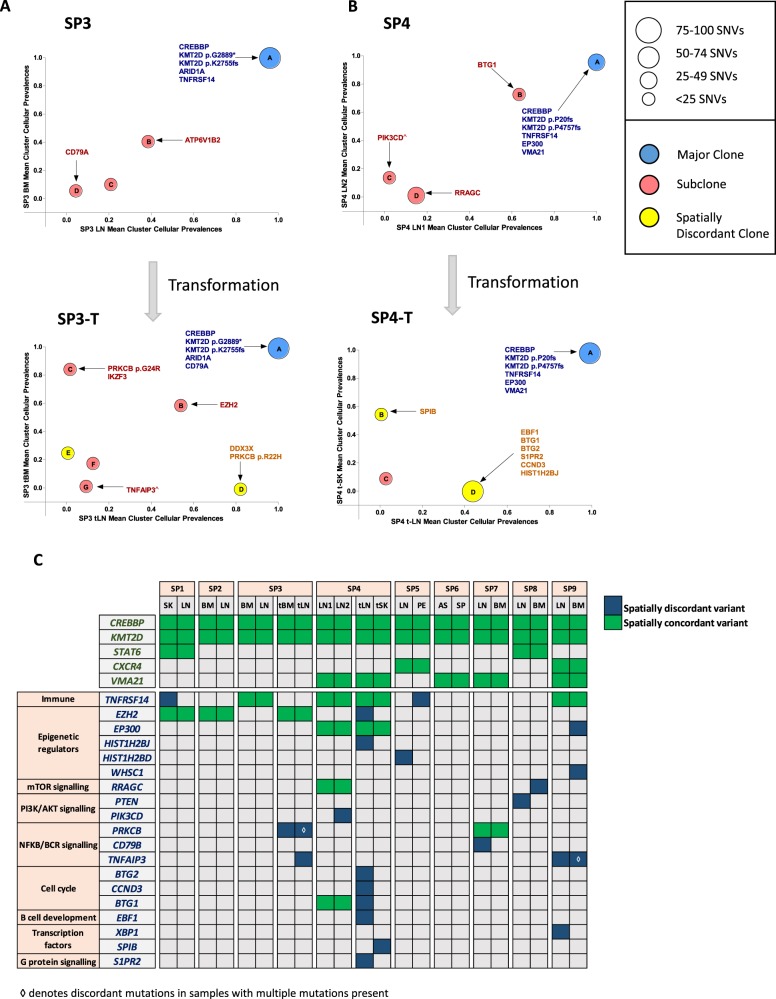

Strikingly, in cases SP3 and SP4, where spatially separated biopsies were profiled at two timepoints (at FL and transformation), the spatial biopsies displayed strong genetic concordance pre-transformation; however, the degree of spatial heterogeneity markedly increased at transformation, with the JSC reducing from 0.92 to 0.61 and 0.68 to 0.50 in SP3 and SP4, respectively. Patient SP3 was treated with chemo-immunotherapy at diagnosis and relapsed 3 years later with transformed disease. Here, all four biopsies (spatial and temporal) shared mutations in ARID1A, CREBBP, KMT2D, 1p36 loss, and 17p gain (Fig. 2a, S4, and Table S7). There was evidence of devolution of specific genetic alterations at progression, with previously identified mutations in ATP6V1B2 and TNFRSF14 not observed, indicating that the transformed biopsies expanded from an ancestral population rather than directly from the dominant diagnostic clone. At transformation, shared temporal changes included acquisition of REL amplification, an EZH2 mutation, and clonal expansion of a CD79A mutation that was present as a rare subclone at diagnosis. Spatial heterogeneity at transformation was illustrated by specific alterations in the transformed LN (tLN) including 6p copy neutral loss-of-heterozygosity (cnLOH) (encompassing the region encoding HLA genes) and mutations in TNFAIP3, PRKCB (p.R22H), and DDX3×. Following the same pattern as SP3, SP4 exhibited a core set of ubiquitous mutations in all biopsies (CREBBP, EP300, KMT2D, and TNFRSF14) with temporal loss of subclonal mutations in PIK3CD and RRAGC. There was a clear increase in ITH at transformation with both site-specific CNAs (Figure S4 and Table S7) and mutations in EBF1, S1PR2, CCND3 (tLN), and SPIB (transformed skin (tSK)) (Fig. 2b). Interestingly, targeted sequencing of 13 selected variants in the circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) sample at transformation detected mutations that were clonal and shared between the spatial biopsies (CREBBP, KMT2D, EP300, and TNFRSF14), but failed to recover all the site-specific variants in the tLN (e.g., EBF1 and S1PR2 corrected VAFs: 21.7% and 38.7%, respectively), indicating that different tumor subpopulations dynamically circulate in the plasma and that ctDNA may not invariably capture the entire genetic spectrum, and warrants further exploration (Figure S5).

Fig. 2.

: Spatial heterogeneity at transformation and in genes with putative biological, prognostic, or therapeutic relevance. a Mean cluster cellular prevalence plot for SP3 at diagnosis (top) and transformation (bottom) to DLBCL. b Mean cluster cellular prevalence plot for SP4 at FL (top) and transformation (bottom) to DLBCL. ^Site-specific variant, although the mean cluster cellular prevalence is reported as marginally subclonal. c Heatmap demonstrating degree of spatial heterogeneity (mutations and copy number changes) in driver genes. At the top, alterations such as those in CREBBP and KMT2D are found in all cases. Gene names listed in green always had spatially concordant variants, while genes listed in blue demonstrate at least one instance of spatial discordance

To determine the clinical relevance of this spatial heterogeneity, we focused on known recurrently altered genes with putative biological, prognostic, or therapeutic relevance in FL (Fig. 2c). Notably, CREBBP was mutated in all nine patients, accompanied by cnLOH (seven cases) and was clonally maintained throughout spatially separated biopsies. This is in keeping with previous reports [2] and reaffirms CREBBP mutations as early events in the pathogenesis of FL. KMT2D was also affected by mutations or cnLOH in all cases, with a tendency for patients to possess multiple mutations with variations in clonality and evidence of genetic convergence with distinct mutations across spatial sites (Fig. 2c). In addition, CXCR4 (SP5, SP9), STAT6 (SP1, SP8), and VMA21 (SP4, SP6, SP7, SP9) mutations were always spatially concordant. Aside from these genes, all others demonstrated spatial discordance in at least one case, with notable examples, including, site-specific mutations in TNFAIP3 (SP3 and SP9), TNFRSF14 (SP1), PIK3CD (SP4), EP300 (SP9), XBP1 (SP9), and copy number loss of PTEN (SP8) (Fig. 2c and S6). Of note, most discordant mutations were detected at a subclonal level (mean corrected VAF 27%; range 3.4–89%). We verified the site-specific and temporal-specific nature of these driver mutations identified from our exome data by performing ultra-deep sequencing of 25 selected variants (mean coverage 8,000×; Table S8 and Figure S7). All variants were confirmed to be truly spatially discordant at VAF sensitivities approaching 0.4%, apart from CBX8 (SP5) confirming their bona fide site-specific nature.

Importantly, even accounting for the rarity of spatial sampling, reflecting the seldom nature spatially involved tumors are procured in routine clinical practice, the subclonal diversity and spatial heterogeneity observed in our case series has potential clinically relevant ramifications for the development of precision-based strategies, particularly in the context of emergent prognostic and predictive biomarkers. This is illustrated by examples of spatially discordant mutations in genes such as EZH2 and EP300 that are integral to the m7-FLIPI prognostic scoring model [10]. Furthermore, the heterogeneity of actionable driver events between sites may mean patients are precluded from adopting the relevant targeted therapy due to failure in the detection of the corresponding predictive biomarker in the solitary tumor biopsy profiled. A potentially attractive treatment paradigm is one whereby we specifically target highly recurrent and truncal gene mutations, such as CREBBP and KMT2D, particularly given their role in FL pathogenesis [11–14], as they may indeed prove to be the Achilles’ heel of these tumors.

In summary, this proof-of-principle study answers an important clinical question that a sole biopsy inadequately captures a patient’s genetic heterogeneity and prompts us to consider integrating multimodal genomic strategies (multiregion, ctDNA, and temporal profiling) into prospective clinical trials, as is currently being performed in the TRACERx study in lung cancer [15], especially as we begin to consider current and future actionable biomarkers.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the patients for donating tumor specimens as part of this study. The authors thank the Centre de Ressources Biologiques (CRB)-Santé of Rennes (BB-0033-00056) for patient samples, Queen Mary University of London Genome Centre for Illumina Miseq sequencing, and the support by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London for Illumina Hiseq sequencing. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health. This work was supported by grants from the Kay Kendall Leukaemia Fund (KKL 757 awarded to J.O.), Cancer Research UK (22742 awarded to J.O., 15968 awarded to J.F., Clinical Research Fellowship awarded to S.A.), Bloodwise through funding of the Precision Medicine for Aggressive Lymphoma (PMAL) consortium, Centre for Genomic Health, Queen Mary University of London, Carte d’Identité des Tumeurs (CIT), Ligue National contre le Cancer, Pôle de biologie hospital universitaire de Rennes, CRB-Santé of Rennes (BB-0033-00056), and CeVi/Carnot program.

Author contributions

J.O. conceived the study; S.A., J.F., J.W., and J.O. designed the study; S.A., J.W., K.K., J.F., and J.O. wrote the manuscript; C.P., J.K.D., P.J., S.M., R.A., J.G.G., and T.A.G. identified patients for the study and collected clinical information; E.K., S.I., and A.C. prepared DNA samples; M.C. performed pathological review of specimens; J.W., C.C., and T.A.G. performed the bioinformatic analysis; S.A., K.K., C.P., E.K., T.R., A.R.-M., and J.H. performed experiments; S.A., J.W., K.K., E.K., T.R., J.H., A.R.-M, and J.O. analyzed the data. All authors read, critically reviewed, and approved the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

Contributor Information

Shamzah Araf, Phone: +442078823804, Email: s.araf@qmul.ac.uk.

Jessica Okosun, Phone: +442078823804, Email: j.okosun@qmul.ac.uk.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41375-018-0043-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Green MR, Gentles AJ, Nair RV, Irish JM, Kihira S, Liu CL, et al. Hierarchy in somatic mutations arising during genomic evolution and progression of follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2013;121:1604–11. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-457283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green MR, Kihira S, Liu CL, Nair RV, Salari R, Gentles AJ, et al. Mutations in early follicular lymphoma progenitors are associated with suppressed antigen presentation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E1116–1125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501199112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kridel R, Chan FC, Mottok A, Boyle M, Farinha P, Tan K, et al. Histological transformation and progression in follicular lymphoma: a clonal evolution study. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002197. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li H, Kaminski MS, Li Y, Yildiz M, Ouillette P, Jones S, et al. Mutations in linker histone genes HIST1H1 B, C, D, and E; OCT2 (POU2F2); IRF8; and ARID1A underlying the pathogenesis of follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2014;123:1487–98. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-500264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okosun J, Bödör C, Wang J, Araf S, Yang CY, Pan C, et al. Integrated genomic analysis identifies recurrent mutations and evolution patterns driving the initiation and progression of follicular lymphoma. Nat Genet. 2014;46:176–81. doi: 10.1038/ng.2856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okosun J, Wolfson RL, Wang J, Araf S, Wilkins L, Castellano BM, et al. Recurrent mTORC1-activating RRAGC mutations in follicular lymphoma. Nat Genet. 2016;48:183–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.3473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pasqualucci L, Khiabanian H, Fangazio M, Vasishtha M, Messina M, Holmes AB, et al. Genetics of follicular lymphoma transformation. Cell Rep. 2014;6:130–40. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ, Horswell S, Larkin J, Endesfelder D, Gronroos E, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:883–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Makohon-Moore AP, Zhang M, Reiter JG, Bozic I, Allen B, Kundu D, et al. Limited heterogeneity of known driver gene mutations among the metastases of individual patients with pancreatic cancer. Nat Genet. 2017;49:358–66. doi: 10.1038/ng.3764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pastore A, Jurinovic V, Kridel R, Hoster E, Staiger AM, Szczepanowski M, et al. Integration of gene mutations in risk prognostication for patients receiving first-line immunochemotherapy for follicular lymphoma: a retrospective analysis of a prospective clinical trial and validation in a population-based registry. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:1111–22. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang Y, Ortega-Molina A, Geng H, Ying HY, Hatzi K, Parsa S, et al. CREBBP inactivation promotes the development of HDAC3-dependent lymphomas. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:38–53. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J, Vlasevska S, Wells VA, Nataraj S, Holmes AB, Duval R, et al. The CREBBP acetyltransferase is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor in B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:322–37. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ortega-Molina A, Boss IW, Canela A, Pan H, Jiang Y, Zhao C, et al. The histone lysine methyltransferase KMT2D sustains a gene expression program that represses B cell lymphoma development. Nat Med. 2015;21:1199–208. doi: 10.1038/nm.3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J, Dominguez-Sola D, Hussein S, Lee JE, Holmes AB, Bansal M, et al. Disruption of KMT2D perturbs germinal center B cell development and promotes lymphomagenesis. Nat Med. 2015;21:1190–8. doi: 10.1038/nm.3940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jamal-Hanjani M, Wilson GA, McGranahan N, Birkbak NJ, Watkins TBK, Veeriah S, et al. Tracking the evolution of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2109–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1616288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andrew Roth, Jaswinder Khattra, Damian Yap, Adrian Wan, Emma Laks, Justina Biele, Gavin Ha, Samuel Aparicio, Alexandre Bouchard-Côté, Sohrab P Shah, (2014) PyClone: statistical inference of clonal population structure in cancer. Nature Methods 11 (4):396-398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.