Abstract

The incidence and mortality rates of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma have been rising worldwide. Few patients present an early-stage disease that is amenable to curative surgery and after resection, high recurrence rates persist. To identify new independent marker related to aggressive behaviour, two prognostic groups of patient were selected and divided according to prognostic performance. All patients alive at 36 months were included in good prognostic performers, while all patients died due to disease within 36 months in poor prognostic performers. Using high-coverage target sequencing we analysed principal genetic alterations in two groups and compared results to clinical data. In the 33 cases included in poor prognosis group, TP53 was most mutated gene (p = 0.011) and exclusively present in these cases. Similarly, ARID1A was exclusive of this group (p = 0.024). TP53 and ARID1A are mutually exclusive in this study. Statistical analysis showed mutations in TP53 and ARID1A genes and amplification of MET gene as independent predictors of poor prognosis (TP53, p = 0.0031, ARID1A, p = 0.0007, MET, p = 0.0003 in Cox analysis). LOH in PTEN was also identified as marker of disease recurrence (p = 0.04) in univariate analysis. This work improves our understanding of aggressiveness related to this tumour type and has identified novel prognostic markers of clinical outcome.

Introduction

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) is the second most common primary hepatic malignancy after hepatocellular carcinoma, and accounts for 10–20% of primary liver cancers1–3. The incidence and mortality rates of ICC have been rising worldwide in the past decade2,3. Moreover, only 10–20% of patients present with early-stage disease that is amenable to curative surgery4,5 and after resection, a high recurrence rate of 50–60% makes for a dismal five-year overall survival (OS) of only 30%5–8. As for patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease that constitute the bulk of newly diagnosed cases, even with the standard treatment of gemcitabine and cisplatin combination chemotherapy their median survival remains less than one year9. Molecular analyses suggested that the observed heterogeneity in prognosis and response to treatments could be attributed to the underlying differential alteration of the molecular mechanisms that drive crucial differences in cancer aggressiveness and treatment outcomes10,11.

In this study, we composed two groups of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas patients with different prognostic performance. Using high-coverage targeted sequencing (HCTS), we investigated somatic mutations and copy number status of a large number of genes that have been identified as frequently altered by previous studies12–15 to uncover the molecular features characterizing the more aggressive subpopulation of this tumour type.

Results

Patient characteristics

A retrospective series (1990–2013) of 66 surgically-resected primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas (ICC) was retrieved from the ARC-Net Biobank at Verona University Hospital. Clinico-pathological characteristics of the sample cohort along with the molecular analyses conducted in this study are reported in Table 1. We selected patients according to the following criteria: i) minimum follow-up of 3 years; ii) availability of material for research; iii) no preoperative therapy received. All patient enrolled were subjected to surgical resection of primary tumour and presented negative liver fluke status. Hepatitis B or C virus (HBV/HCV) infection was present in 4/66 (6.1%) cases while liver fluke status was negative for all patients. Liver cirrhosis was present in 7/66 (10.6%) patients. Overall survival (OS) was available for all patients, while disease free survival (DFS) for 42 patients. The whole cohort of patients showed a median follow up of 40.7 months (range 2.0–152.7).

Table 1.

Clinico-pathological features of 66 intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas included in the study.

| Clinico-pathological features | Poor 33 | Good 33 | Total 66 | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 9F 24M | 16F 17M | 25F 41M | 0.13 |

| Age | 67.8 ± 9.7 | 60.6 ± 13.6 | 65.0 ± 11.8 | 0.334^ |

| Dimension (cm) | 6.7 ± 4.4 | 6.1 ± 2.6 | 6.4 ± 3.6 | 0.478^ |

| Median Follow-up (months) | 17.1 | 61.3 | 40.7 | <0.0001# |

| Range | (2.0–40.0) | (40.7–152.7) | (2.0–152.7) | |

| Median DFS (months) | 7.4 | 61.7 | 14.2 | <0.0001# |

| Range | (2.8–26.4) | (34.0–152.7) | (6.3–152.7) | |

| NA | 10 | 14 | 24 | |

| Recurrence | ||||

| 1 | 22 | 11 | 33 | 0.006 |

| 0 | 1 | 8 | 9 | |

| NA | 10 | 14 | 24 | |

| TNM Stage | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 10 | 12 | 0.084 |

| 2 | 12 | 8 | 20 | |

| 3 | 7 | 5 | 12 | |

| 4 | 12 | 10 | 22 | |

| Grade | ||||

| 1 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 0.226 |

| 2 | 19 | 24 | 43 | |

| 3 | 11 | 5 | 16 | |

| R | ||||

| 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.278 |

| 1 | 5 | 2 | 7 | |

| 0 | 27 | 31 | 58 | |

| Liver fluke status | ||||

| Positive | 0 | 0 | 0 | — |

| Negative | 33 | 33 | 66 | |

| HBV/HCV infection | ||||

| Positive | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0.11 |

| Negative | 29 | 33 | 62 | |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | ||||

| Positive | 0 | 0 | 0 | — |

| Negative | 33 | 33 | 66 | |

| Biliary stone disease | ||||

| Positive | 0 | 1 | 1 | — |

| Negative | 33 | 32 | 65 | |

| Liver cirrhosis | ||||

| Positive | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0.011 |

| Negative | 26 | 33 | 59 | |

| Multiple nodes | ||||

| Present | 16 | 10 | 26 | 0.207 |

| Absent | 17 | 23 | 40 | |

| Presence of BIN | ||||

| Present | 8 | 3 | 11 | 0.185 |

| Absent | 25 | 30 | 55 | |

| Vascular invasion | ||||

| Present | 28 | 20 | 48 | 0.051 |

| Absent | 5 | 13 | 18 | |

| Perineural invasion | ||||

| Present | 17 | 13 | 30 | 0.458 |

| Absent | 16 | 20 | 36 | |

Note: BIN, biliary intraepithelial neoplasia; DFS, disease free survival; NA, not available; R, resection margins. *Fisher exact test for multiple comparison was used as appropriated; ^Unpaired t-test; # Kaplan-Maier analysis.

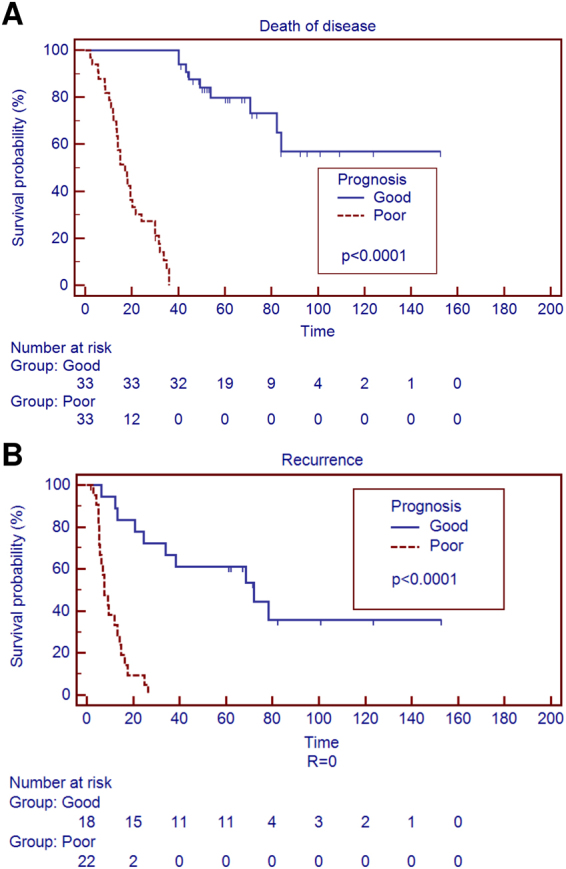

Patient grouping according to prognostic performance

For the present study, the sixty-six patients were divided into two groups based on clinical performance: patients alive at least 36 months (33 patients) were defined as good prognostic performers (GP group) and patients dead of disease within 36 months (33 patients) as poor prognostic performers (PP group). The PP group had a median follow up of 17.1 months (range 2.0–36.0) whereas the GP group had a median follow up of 61.3 (range 40.7–152.7). Clinicopathological characteristics of these two groups and of the whole cohort are shown in Table 1 and further detailed in Supplementary Table S1. Patient’s stratification is illustrated in Fig. 1. A higher rate of disease recurrence (p = 0.0006; Table 1) and a shorter time to recurrence among patients with negative resection margins (p < 0.0001; Fig. 1B) was observed in the PP group. Moreover, presence of liver cirrhosis was observed only in 7 patients of the PP group (p = 0.011). No differences were found for the other variables.

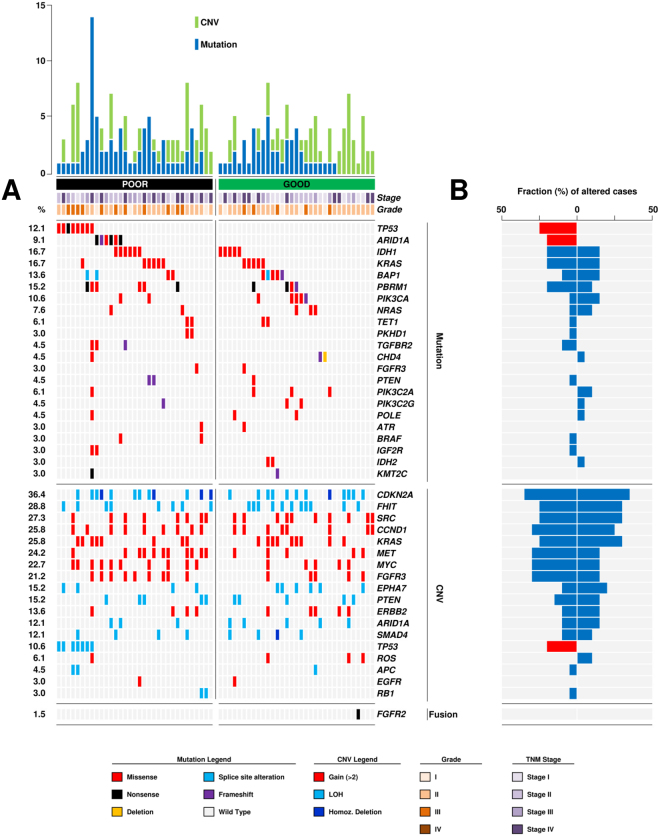

Figure 1.

Grouping according to prognosis of 66 intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas. (A) Overall survival significantly divided 66 intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in two prognostic performers group according to clinical outcome (p < 0.0001). (B) Prognostic grouping also divided intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas characterized by negative resection margins in two different groups (p < 0.0001).

Molecular features according to prognosis

DNA of tumour/normal matched samples from all cases was successfully amplified in multiplex PCR for 90 relevant genes chosen on the basis of published ICC sequencing studies, and an adequate library for HCTS was obtained. The mean read length was 109 bases and a mean coverage depth of 2537x was achieved, with 87.9% target bases covered more than 100x. A minimum coverage of 20x was obtained in all cases. More specifically, HCTS yielded an average coverage of 1347x (40–3874x) in normal samples and 3728x (259–24725X) in tumour samples. Further detail of coverage depth per sample is reported in Supplementary Table S2.

The most frequently altered genes are shown in Fig. 2, distribution and frequencies of mutations in all 90 genes analysed are detailed in Table 2 and Supplementary Table S3. Copy number variations (CNVs) were assessed in 18 genes and the results are reported in Table 3. FISH validation of representative cases affected by loss of heterozygosity (LOH) and rearrangement of FGFR2 are illustrated in Supplementary Figures S1 and S2 respectively.

Figure 2.

Genetic alterations distinguished two prognostic performer groups. (A) Cases are grouped according to prognostic group (poor and good) previous defined by clinical outcome. The upper histogram shows the number of mutations (blue) and CNV (green) in recurrently altered genes for each sample. The central matrix shows 22 genes that were mutated in at least two cases of the whole cohort, 18 genes altered in copy number and 3 genes shown rearrangement; alterations are annotated by different colour according to their impact on the gene product as illustrated in panel below. The number on the left reports the alteration frequency of each gene expressed as a percentage. (B) Fraction (%) of cases altered for each gene is represented by blue box or red box (when a statistical significant distribution was observed) according to prognostic group (poor prognosis on the left; good prognosis on the right).

Table 2.

Detailed mutational prevalence analysis of 66 intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas. Related to Fig. 2.

| Gene | Poor | Good | Total | Mutation type | p-value* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 33 | [%] | 33 | [%] | 66 | [%] | M | N | S | D | F | ||

| ALK | 1 | [3.0] | 1 | [1.5] | 1 | — | ||||||

| APC | 1 | [3.0] | 1 | [1.5] | 1 | — | ||||||

| ARAF | 1 | [3.0] | 1 | [1.5] | 1 | — | ||||||

| ARID1A | 6 | [18.2] | 6 | [9.1] | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0.024 | ||||

| ARID1B | 1 | [3.0] | 1 | [1.5] | 1 | — | ||||||

| ATR | 1 | [3.0] | 1 | [3.0] | 2 | [3.0] | 2 | — | ||||

| BAP1 | 4 | [12.1] | 5 | [15.2] | 9 | [13.6] | 5 | 3 | 1 | — | ||

| BRAF | 2 | [6.0] | 2 | [3.0] | 2 | — | ||||||

| CHD4 | 1 | [3.0] | 2 | [6.0] | 3 | [4.5] | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | ||

| ERBB3 | 1 | [3.0] | 1 | [1.5] | 1 | — | ||||||

| ERBB4 | 1 | [3.0] | 1 | [1.5] | 1 | — | ||||||

| FBXW7 | 1 | [3.0] | 1 | [1.5] | 1 | — | ||||||

| FGFR3 | 1 | [3.0] | 1 | [3.0] | 2 | [3.0] | 2 | — | ||||

| HRAS | 1 | [3.0] | 1 | [1.5] | 1 | — | ||||||

| IDH1 | 6 | [18.2] | 5 | [15.2] | 11 | [16.7] | 11 | — | ||||

| IDH2 | 2 | [6.0] | 2 | [3.0] | 2 | — | ||||||

| IGF2R | 2 | [6.0] | 2 | [3.0] | 2 | — | ||||||

| KDR | 1 | [3.0] | 1 | [1.5] | 1 | — | ||||||

| KIT | 1 | [3.0] | 1 | [1.5] | 1 | — | ||||||

| KMT2C | 1 | [3.0] | 1 | [3.0] | 2 | [3.0] | 1 | 1 | — | |||

| KMT2D | 1 | [3.0] | 1 | [1.5] | 1 | — | ||||||

| KRAS | 6 | [18.2] | 5 | [15.2] | 11 | [16.7] | 11 | — | ||||

| MET | 1 | [3.0] | 1 | [1.5] | 1 | — | ||||||

| MLH1 | 1 | [3.0] | 1 | [1.5] | 1 | — | ||||||

| MTOR | 1 | [3.0] | 1 | [1.5] | 1 | — | ||||||

| NF1 | 1 | [3.0] | 1 | [1.5] | 1 | — | ||||||

| NRAS | 2 | [6.0] | 3 | [9.1] | 5 | [7.6] | 5 | — | ||||

| PBRM1 | 6 | [18.2] | 4 | [12.1] | 10 | [15.2] | 5 | 4 | 1 | — | ||

| PDGFRA | 1 | [3.0] | 1 | [1.5] | 1 | — | ||||||

| PIK3C2A | 1 | [3.0] | 3 | [9.1] | 4 | [6.1] | 4 | — | ||||

| PIK3C2G | 1 | [3.0] | 2 | [6.0] | 3 | [4.5] | 2 | 1 | — | |||

| PIK3CA | 2 | [6.0] | 5 | [15.2] | 7 | [10.6] | 6 | 1 | — | |||

| PKHD1 | 2 | [6.0] | 2 | [3.0] | 2 | — | ||||||

| PLCG1 | 1 | [3.0] | 1 | [1.5] | 1 | — | ||||||

| POLE | 1 | [3.0] | 2 | [6.0] | 3 | [4.5] | 3 | — | ||||

| POLQ | 1 | [3.0] | 1 | [1.5] | 1 | — | ||||||

| PTEN | 2 | [6.0] | 1 | [3.0] | 3 | [4.5] | 1 | 2 | — | |||

| PTPN11 | 1 | [3.0] | 1 | [1.5] | 1 | — | ||||||

| RASA | 1 | [3.0] | 1 | [1.5] | 1 | — | ||||||

| STK11 | 1 | [3.0] | 1 | [1.5] | 1 | — | ||||||

| TET1 | 2 | [6.0] | 2 | [6.0] | 4 | [6.1] | 4 | — | ||||

| TGFBR2 | 3 | [9.1] | 3 | [4.5] | 2 | 1 | — | |||||

| TP53 | 8 | [24.2] | 8 | [12.1] | 7 | 1 | 0.011 | |||||

Note: M. missense; N. nonsense; S. splite site alteration; D. deletion; F. frameshift.

*Fisher test for multiple comparison was used as appropriated.

Table 3.

Detailed distribution of copy number variations detected in 66 intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas. Related to Fig. 2.

| Gene | Poor | Good | Total | p-value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 33 | [%] | 33 | [%] | 66 | [%] | ||

| APC | 2 | [6.1] | 1 | [3.0] | 3 | [4.5] | — |

| ARID1A | 3 | [9.1] | 5 | [15.2] | 8 | [12.1] | — |

| CDKN2A | 12 | [36.4] | 12 | [36.4] | 24 | [36.4] | — |

| CCND1 | 9 | [27.3] | 8 | [24.2] | 17 | [25.8] | — |

| EGFR | 1 | [3.0] | 1 | [3.0] | 2 | [3.0] | — |

| EPHA7 | 4 | [12.1] | 6 | [18.2] | 10 | [15.2] | — |

| ERBB2 | 4 | [12.1] | 5 | [15.2] | 9 | [13.6] | — |

| FGFR3 | 9 | [27.3] | 5 | [15.2] | 14 | [21.2] | — |

| FHIT | 8 | [24.2] | 11 | [33.3] | 19 | [28.8] | — |

| KRAS | 8 | [24.2] | 9 | [27.3] | 17 | [25.8] | — |

| MET | 11 | [33.3] | 5 | [15.2] | 16 | [24.2] | 0.15 |

| MYC | 10 | [30.0] | 5 | [15.2] | 15 | [22.7] | 0.24 |

| PTEN | 5 | [15.2] | 5 | [15.2] | 10 | [15.2] | — |

| RB1 | 2 | [6.1] | 2 | [3.0] | — | ||

| ROS | 1 | [3.0] | 3 | [9.1] | 4 | [6.1] | — |

| SMAD4 | 4 | [12.1] | 4 | [12.1] | 8 | [12.1] | — |

| SRC | 8 | [24.2] | 10 | [30.3] | 18 | [27.3] | — |

| TP53 | 7 | [21.2] | 7 | [10.6] | 0.024 | ||

*Fisher test for multiple comparison was used as appropriated.

Mutations in one or more of the 90 analysed genes were observed in 56 cases (84.8%) of our series. In detail: one mutation was observed in 26 cases (39.4%), two or more in 30 cases (45.4%) while no alteration in 10 cases (15.2%). The most frequently mutated genes across the whole cohort were IDH1, KRAS (11 mutated cases each; 16.7%), PBRM1 (10 cases; 15.2%) and BAP1 (9 cases; 13.6%).

CNVs for one or more of the 18 analysed genes were observed in 59 cases. In detail: one CNV was observed in 6 cases (9.1%), more than one in 46 cases (69.7%) while no CNV was observed for 7 cases (10.6%). CNV analysis showed that loss of heterozygosis (LOH) or homozygous deletion (HD) of CDKN2A was most frequent event (24 cases; 36.4%), followed by LOH at the FHIT locus (19 cases; 28.8%) and copy gain of SRC (18 cases; 27.3%).

To further complement mutation and CNV analysis, all cases were screened through break-apart FISH probe to detect rearrangement of FGFR2, FGFR3 and ROS1 genes. A cut-off of 20% was used to define positive specimens. Only one case showed rearrangement at the FGFR2 gene locus (Supplementary Figure S2). No other rearrangement was observed for FGFR3 and ROS1 at the defined cut-off of 20%.

Comparing the two prognostic groups (PP and GP), different mutational rates were observed: a mean of 2.3 mutations per sample was obtained for the PP group whereas the average mutation rate was 1.5 for the GP group (Unpaired t-test p = 0.0007). Furthermore, one hyper-mutated sample was identified in the PP group, that is a sample characterized by a gross excess of point mutations relative to the same tumour type as analysed here and reported in current literature15–19. In particular, this case showed a missense mutation in POLE, a gene already linked to hyper-mutated genomic profiles in previous studies20,21. Two cases without mutations were observed in the PP group while in GP groups 8 cases showed no mutation. Differences between groups were observed in the number of CNVs as well, albeit not statistically significant. A mean of 3.3 CNVs per sample was observed in the PP group vs. a mean of 2.9 in the GP group.

As for altered genes prevalence (Fig. 2, Table 2), TP53 was the most frequently mutated gene of the PP group (8 cases; 24.2%; p = 0.011) and its mutation was exclusive to this group. ARID1A, IDH1, KRAS and PBRM1 displayed the second highest alteration frequency in the very same group (6 cases; 18.2%). ARID1A mutation was exclusive to this group as well (p = 0.024), and mutually exclusive with TP53 mutation. Of note, mutations of TGFBR2 (3 cases; 9.1%), BRAF and IGF2R (2 cases each; 9.1%) were present exclusively in the PP group, albeit at low rates. As for CNVs (Table 3), loss of one or both copies of CDKN2A and copy gain of MET (12 cases; 36.4%) were the most frequent events followed by copy gains in MYC (10 cases; 30.3%). LOH of TP53 was particularly enriched in this group (7 cases; 21.2%; p = 0.024) and associated to mutation at the same locus.

The 33 patients included in GP group had exclusive mutations in IDH2 (2cases; 3.0%), APC, ARAF, POLQ and RASA (1 case each; 1.5%), while it shared mutations in KRAS, IDH1, BAP1 and PIK3CA (5 cases each; 15.2%) with the PP group. As for CNVs, the loss of CDKN2A was the most frequent event in the GP group (12 cases; 36.4%), a feature shared with the PP group. The second most frequent event was LOH at FHIT locus (11 cases; 33.3%). MYC copy gain (5 cases; 15.2%) was less frequently altered than in the PP group.

Survival analysis identified markers of poor outcome and disease recurrence

Pathological features were matched to clinical data to identify poor prognostic markers. Grade, stage, sex and resection margins status were tested. Presence of positive resection margins (p < 0.0001) and advanced stage (p = 0.026) were identified as poor prognostic markers.

To investigate which of the previously identified molecular feature had the greatest impact on aggressive behaviour, we compared overall survival and progression free survival (PFS) curves in presence vs. absence of a specific alteration by univariate analysis.

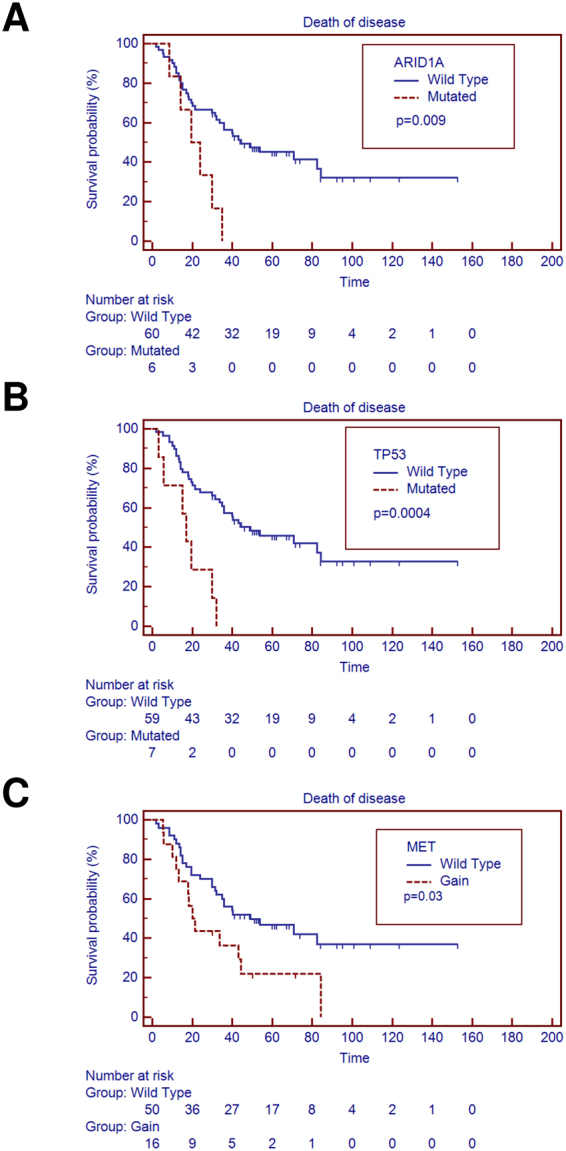

Considering the whole cohort, we assessed the prognostic impact of principal differently distributed molecular alterations between GP and PP groups: mutations in TP53; mutations in ARID1A; copy gains in MET; copy gains in MYC. LOH in TP53 was not considered because already included in the TP53 mutated cases. As illustrated in Fig. 3, alterations in TP53 (p = 0.0004), ARID1A (p = 0.009) and MET (p = 0.03) genes but not gain in MYC gene (p = 0.065) were predictors of poorer prognosis at univariate analysis.

Figure 3.

Univariate analysis identified poor prognostic markers in whole cohort. (A) Overall survival is significantly affected by mutations in ARID1A gene (p = 0.009); (B) TP53 gene (p = 0.0004) mutations and (C) copy gain in MET gene (p = 0.03).

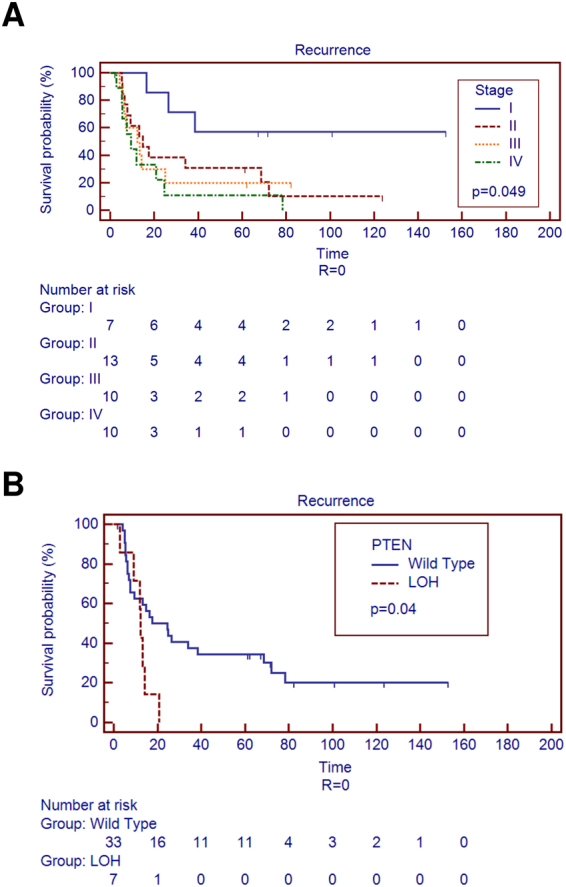

Aggressive behaviour, measured as power of relapse, was tested using disease free survival and recurrence status in the 40 patients of our cohort that displayed negative resection margins. To perform this, we compared progression free survival (PFS) of these 40 cases grouping them on the basis of their clinicopathological and molecular features. At univariate analysis, we identified advanced tumour stage (p = 0.049) and LOH at PTEN gene locus (p = 0.04) as markers of earlier disease recurrence (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Univariate analysis identified markers of disease recurrence in negative resection margins cases. (A) Disease recurrence is significantly affected by advanced stages and (B) LOH of PTEN gene.

Cox regression for multivariate survival analysis was used to test the independent prognostic value in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas of the previously identified molecular markers, selecting as candidates those characterized by a p-value under 0.2 at univariate analysis. For clinical outcome, we tested the association of overall survival to mutation in TP53 and ARID1A, gains affecting MET and MYC loci, tumour stage, grade and resection margins status. Results are summarized in Table 4 and show that the resulting independent molecular predictors of poor outcome were mutation of TP53 (p = 0.0031) and ARID1A (p = 0.0007), and copy gain of MET (p = 0.0003).

Table 4.

Multivariate survival analysis of 66 intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas; median overall survival was 40.7 months and 41 subjects died of disease.

| Covariate | Odds-ratio | 95% CI | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| TP53 wild type | 1 | — | — |

| TP53 mutated | 5.458 | 1.7729 to 16.8033 | 0.0031 |

| ARID1A wild type | 1 | — | — |

| ARID1A mutated | 6.9059 | 2.2710 to 21.0008 | 0.0007 |

| MET wild type | 1 | — | — |

| MET gain | 4.6312 | 2.0210 to 10.6126 | 0.0003 |

| MYC wild type | 1 | — | — |

| MYC gain | 1.6521 | 0.7391 to 3.6929 | 0.2212 |

| Stage I | 1 | — | — |

| Stage II | 1.8791 | 0.4878 to 7.2383 | 0.3592 |

| Stage III | 7.4306 | 2.0001 to 26.6060 | 0.0027 |

| Stage IV | 2.7035 | 0.7327 to 9.9752 | 0.1354 |

| Grade 1 | 1 | — | — |

| Grade 2 | 0.7426 | 0.1978 to 2.7885 | 0.6593 |

| Grade 3 | 2.09 | 0.5534 to 7.8932 | 0.2769 |

| Negative resection margins | 1 | — | — |

| Positive resection margins | 4.4314 | 1.4418 to 13.5611 | 0.0091 |

*Cox proportional-hazards regression analysis. Selection of the best model was performed using the “forward” algorithm.

Protein expression evaluation of principal markers

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed on all samples included in the study to evaluate protein expression level of candidate gene markers previous identified. We observed positive stain for p53 in all samples affected by missense mutation, while the case affected by a nonsense mutation showed no protein expression (Supplementary Figure S3A).

Similarly, arid1a immunolabelling was negative in presence of nonsense and frameshift mutations but not when samples were unaffected or affected by missense mutations (Supplementary Figure S3B).

As for pten protein, we observed a generally low or negative immunolabelling irrespective of the presence of LOH, mutation, or no alteration at all.

Finally, we observed positive immunolabelling for c-met protein in those cases which had the MET locus affected by copy gain (Supplementary Figure S3C).

Discussion

The incidence and mortality rates of ICC have been rising worldwide in the past decade2 and only 10–20% of patients present with an early-stage disease amenable to curative surgery4,5. Molecular analyses have suggested that the observed heterogeneity in prognosis and response to treatments could be attributed to the underlying molecular mechanisms driving crucial differences in cancer aggressiveness and treatment outcomes11.

To date, many studies have been performed to uncover molecular features characterizing the different subtypes of cholangiocarcinoma and to infer mechanisms underlying its aggressive behaviour. Recently, two multi-omics studies were performed in unbiased large cohorts of cholangiocarcinomas identifying poor prognostic hallmarks15,19. In particular, Nakamura et al. identified shorter survival in a group characterized by a higher mRNA expression of immune checkpoint genes15 while, Jusakul et al. identified the presence of liver fluke infection as a marker for poor prognosis19. In both studies a heterogeneous cholangiocarcinoma cohort (including gallbladder, extrahepatic and intrahepatic tumours) was used and survival analysis was performed on groups characterized by concomitant multiple alterations. Identification of these simultaneous alterations in diagnostic routine remains expensive and difficult to apply on archive material. Focusing on the intrahepatic subtype, to date several molecular studies were performed. In these, aside from mutations in TP5314,15,22,23, other different molecular alterations were identified as poor prognosis markers as IDH112, RNF4324, KRAS and ARID215. In all these studies, the experimental rationale was to start from a histopathologically defined cohort to identify new molecular and prognostic markers.

In this study, we followed a different experimental approach, using HCTS to analyse genetic alterations in two cohorts of ICC previously grouped according to their different prognostic performance. The idea of molecularly characterizing different prognostic groups in order to investigate the potential existence of different driver alterations is innovative and promising, yet conceptually similar to treatment response trials or previous research works where clinicopathological variables were compared between 2 subgroups of patients distinct according to treatment response25 or prognosis26.

We selected and grouped 66 patients in two sub-cohorts according to the clinical performance showed within 36 months: PP group (dead of disease at <36 months) and GP group (alive at >36 months). We confirmed a statistically significant difference between the two groups both for the prognostic performance in all cases (p < 0.0001) and for disease recurrence in negative resection margin cases (p < 0.0001).

Sequencing analysis evidenced different mutational rates between groups (p = 0.0033), with poor prognostic performers bearing a higher number of mutations, in keeping with a recent study in which a hyper-mutated profile was associated to poorer prognosis15. Mutational analysis identified IDH1, BAP1, PBRM1 and KRAS as the most frequently altered genes, as in previous whole-exome and whole-genome sequencing studies12,13,15. Of note, coding sequence mutations of TP53 were found only in poor prognostic performers in our study, with a significant discrepancy (p = 0.011) between groups. Similarly, we found mutations of ARID1A only in this prognostic group (p = 0.024). The association between mutations in TP53 and poor prognosis is not novel for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas15,22,23,27. In particular, Jayle et al. showed similar results in a large unbiased group of 224 ICCs where TP53 resulted mutated in 24% of cases23. Differently, to date only low expression of ARID1A protein and mRNA were associated to poor prognosis in 57 intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas analysed by Yang and colleagues. Although this corroborates our finding in suggesting a prognostic role of ARID1A in ICC, unfortunately no mutational analysis was performed in that study28. Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis of Luchini et al. showed as mutation or low expression of ARID1A is a predictor of shorter disease specific survival and time to disease recurrence in cancer patients, but a direct correlation to ICC was not evident29.

Copy number variation analysis identified LOH in CDKN2A as the most frequent event, in keeping with previous studies15,30, with no difference in alteration rates between the two groups. Conversely, a higher proportion of cases affected by copy gain in MET and in MYC genes was observed in the PP group. The association between c-MET and poor prognosis is not novel, as a previous study showed by immunohistochemistry that overexpression of this proto-oncogene is correlated to poorer outcome in patients affected by cholangiocarcinoma31. However, we herein show for the first time that patients affected by MET and MYC gene copy gain associate to a worse prognosis, suggesting that the enhanced expression of these loci may be due to a genetic lesion at least in a fraction of cases.

When we considered only cases with negative resection margins, only alterations affecting PTEN showed a prognostic impact on disease recurrence. Recently, heterozygous and homozygous deletion of PTEN locus in presence of KRAS activation was demonstrated to induce intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in cholangiocytes of a new mouse model32 showing an important role of PTEN in the development of this tumour type.

The main strength of the present work was the selection and focus on a well-defined cohort of resected ICC cases, grouped by prognostic performance. This however leads directly to the main limitation of the study, that suffers from a relatively small sample due to the difficulties in enrolling large numbers of resected patients with a minimum follow-up of 3 years, availability of material for research and no preoperative therapy. Despite that, our study shows a clear overlap with previous studies when dealing with already known associations (e.g. TP53 mutation), while providing several interesting evidences about independent poor prognostic markers for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas. The preliminary stratification of patients according to prognosis also allowed the identification of some molecular aberrations whose absence in the GP group could explain an unusual degree or duration of the clinical benefit in selected cases of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, as opposed to an otherwise relatively ineffective treatment in the rest of patients. The present work therefore confirms previous knowledge on the molecular landscape of ICC and suggests potential hallmarks of aggressiveness in this tumours that demand further validation but may be easily translated to the clinic for anticipating prognosis and response to therapy.

Materials and Methods

Patients and samples enrolled in the study

Tissue specimens and data from surgically-resected primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma patients were retrieved from the ARC-Net Biobank at Verona University Hospital. Three criteria were considered to enrol patients in this study: i) minimum follow-up of 3 years; ii) availability of material for research; iii) no preoperative therapy received. According to the stated criteria, a retrospective series (1990–2013) of 66 surgically-resected primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas (ICC) was retrieved from the FFPE archives of the biobank under the local ethics committee approval (“Comitato etico per la sperimentazione clinica delle province di Verona e Rovigo” n. prog. 1959). All cases were reclassified by two pathologists (MF and AS) according to WHO 201033 and staged according to AJCC/UICC 7th edition34. In all cases, sufficient material for molecular analysis and construction of 1-mm cores tissue microarrays (TMAs) was available. Three tissue cores per case were included in the TMAs. Eighteen non-neoplastic samples (8 normal biliary duct and 10 chronic cholecystitis) were included in the TMAs as controls.

DNA extraction and qualification

DNA from tumour and matched non-neoplastic liver was extracted from formalin-fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissue specimens. In particular, tumour DNA was prepared after enriching neoplastic cellularity to at least 70% by manual microdissection of 10 consecutive 4-μm sections: cases were revised by a pathologist that chose tissue areas according to two main features: i) absence of necrosis and ii) tissue histology had to be representative of the whole tumour. DNA was purified using the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen), and qualified as reported elsewhere35,36.

Mutational analysis by next-generation targeted sequencing

Matched tumour/normal DNA from all cases was subjected to targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS). Two multigene panels were used to investigate mutational status of 90 genes: the 50-gene Ion AmpliSeq Cancer Hotspot panel v2 (Thermo Fisher) and one AmpliSeq custom panel (ICC custom panel 1) targeting 40 genes not included in the commercial panel. The first explores selected regions of 50 cancer-genes: ABL1, AKT1, ALK, APC, ATM, BRAF, CDH1, CDKN2A, CSF1R, CTNNB1, EGFR, ERBB2, ERBB4, EZH2, FBXW7, FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3, FLT3, GNA11, GNAS, GNAQ, HNF1A, HRAS, IDH1, IDH2, JAK2, JAK3, KDR/VEGFR2, KIT, KRAS, MET, MLH1, MPL, NOTCH1, NPM1, NRAS, PDGFRA, PIK3CA, PTEN, PTPN11, RB1, RET, SMAD4, SMARCB1, SMO, SRC, STK11, TP53, VHL. Details on target regions of the commercial panel are at http://www.thermofisher.com. The custom panels targets 40 genes selected on the basis of published WGA, exome and targeted sequencing studies: ACVR2A, ARAF, ARID1A, ARID1B, ARID2, ATR, BAP1, CHD4, DNMT3A, ELF3, EP300, EPHA2, EPHA6, EPHA7, GSK3A, HERC2, KMT2A, KMT2C, KMT2D, MDC1, MSH6, MTOR, NF1, PBRM1, PIK3C2A, PIK3C2G, PKHD1, PLCG1, POLE, POLQ, PRKDC, RASA, RELN, RNF43, ROBO2, ROS, SF3B1, TET1, TET2, TGFBR212–15,24. Details on target regions of the commercial panel are at http://www.thermofisher.com while detail of region covered by ICC custom panel 1 are reported in Supplementary Table S4. Twenty ng of DNA were used for each multiplex PCR amplification. The quality of the obtained libraries was evaluated by Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer on-chip electrophoresis (Agilent Technologies). Emulsion PCR for clonal amplification of the libraries was performed with the Ion OneTouch™ OT2 System (Thermo Fisher). Sequencing was run on the Ion Proton (PI, Thermo Fisher) loaded with Ion PI Chip v2. Data analysis, including alignment to the hg19 human reference genome and variant calling, was done on the Torrent Suite Software v.5.0 (Thermo Fisher) utilizing the standard setup for somatic variants detection with minor modifications to further improve sensitivity (i.e. minimum variant frequency for indels was set to 0.05 instead of 0.15; complex variant detection was enabled). Called variants were annotated using a custom pipeline based on vcflib (https://github.com/ekg/vcflib), SnpSift37, the Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) software38 and NCBI RefSeq database. Confident somatic mutations were obtained from annotated variants by: i) filtering-out germline mutations identified in matched normal sample sequenced; ii) filtering-in mutations with at least 20 variant-containing reads and with variant frequency >10%; iii) ruling out sequencing artefacts by visual verification of normal and tumour samples alignments using the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) v2.339. Alignments were visually verified with IGV also to confirm the presence of identified mutations.

Copy number variations of cholangiocarcinomas by next-generation sequencing

A second custom panel was specifically developed to investigate CNV status of 18 genes: APC, ARID1A, CDKN2A, CCND1, EGFR, EPHA7, ERBB2, FGFR3, FHIT, KRAS, MYC, MET, PTEN, RB1, ROS, SMAD4, SRC and TP53 (ICC custom panel 2, Supplementary Table S4). CNV analysis was performed on IonReporter Software v.5.0 (Thermo Fisher) utilizing the single-sample CNV workflow. According to this workflow, a baseline was created using the alignment files of 10 DNA samples from FFPE tissue of male healthy donors. Alignment files of tumour samples were then compared to the CNV baseline to determine CNV status. CNV calls were deemed confident according to the following criteria: i) a CNV confidence number major than 20; ii) a tiles number major than 10. For genes showing CNV calls with sub-optimal values, an orthogonal cross-validation using FISH or qPCR was performed. In this case, only CNV calls with concordant results of NGS and validation were reported. A statistical report of cross-validation rates is illustrated in Supplementary Table S5.

CNV validation by Quantitative PCR

Q-PCR analysis of copy numbers was applied to all samples for selected loci. All target and reference assays were purchased from Applied Biosystems. RNaseP was used as endogenous control for normalization of analysed loci. The following assays were used: CCND1 (Hs03772544), FHIT (Hs03491211), MET (Hs04951661), SRC (Hs07169853) and RNaseP (part number 4403326). The experimental procedure recommended by the manufacturer (Applied Biosystems) was followed. Twenty ng of genomic DNA were used in the q-PCR reaction and a negative control was analysed in parallel. All q-PCR reactions were run in quadruplicate in a 7900HT qRT-PCR machine (Applied Biosystems) using standard cycling conditions of 10 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of [95 °C for 15 sec and at 60 °C for 1 min]. Pooled normal FFPE DNA was used as calibrator.

Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH)

A FISH analysis was developed according manufacturer instruction for following genes to validate Copy Number Variation obtained by NGS analysis: CDKN2A, EGFR, ERBB2, FGFR3, MYC, MET, PTEN, ROS and TP53 (all probes Vysis/Abbott Molecular). Analysis was performed for all samples; data interpretation was performed as reported elsewhere40–43 and cross-validation rates are illustrated in Supplementary Table S5. FISH analysis was also used to identify rearrangement for followed genes: FGFR2 (ZytoVision Molecular Diagnostics), FGFR3 (CGI) and ROS1 (Vysis/Abbott Molecular). FISH analysis was firstly performed on TMA for all cases. Cases showing a positive signal in at least 15% of nuclei were re-analysed by FISH on whole sections. A presence of rearrangement in at least 20% of cells was considered positive. Representative cases of PTEN and TP53 monosomy and CDKN2A homozygous deletion are illustrated in Supplementary Figure S1, while the only case with confirmed FGFR2 rearrangement is shown in Supplementary Figure S2.

Immunohistochemistry

The immunohistochemical staining was performed with a Leica Microsystems Bond-Max Autostainer System according to manufacturer protocols. Arid1a (clone EPR13501–73, Abcam, dilution 1:1000), met (clone 4F8.2, Sigma Aldrich, dilution 1:250), pten (clone 138G6, Cell Signaling, dilution 1:100) and p53 (clone DO-1, Immunotech, dilution 1:50) were applied to consecutive 4-μm FFPE TMA sections. Appropriate positive and negative controls were run concurrently. Representative cases altered in p53, arid1a and met are shown in Supplementary Figure S3.

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA, Kruskal-Wallis test, Fisher’s test with Monte Carlo simulation, and Fisher’s exact test corrected for multiple comparisons were used as appropriate. For comparison of Kaplan-Meier survival curves, Mantel-Cox log-rank test was used; for multivariate survival analysis, stepwise Cox proportional hazards regression was used; selection of the best model was performed using the “backward elimination” algorithm. For all the analyses, a p-value below 0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed using Medcalc for Windows version 15.6 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium) and R v. 3.2.1; multivariate Cox regression was done with R using survival library v.2.38-2.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by Italian Cancer Genome Project, Ministry of University and Research (FIRB RBAP10AHJB); Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC grants n. 12182) to AS. EB is supported by the Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC grant no. 20583). The funding agencies had no role in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data and in the writing of the manuscript.

Author Contributions

E.B. conceived the study. M.S. designed the study and validation experiments. C.V., M.B., S.P. performed and interpreted FISH results. V.C. supervised the validation experiments. R.T.L. coordinated patient’s sample, data management, and supervised ethical protocols. A.R., S.C., C.B., S.C. and A.G. collected materials and clinical data. M.F., P.C., B.R., A.S. analysed histopathological data. M.F., B.R. microdissected samples. GT DNA extraction. M.S. and A.M. carried out sequencing and raw data analysis. A.M. and M.S. performed bioinformatic analysis. M.S. and C.V. performed Q-PCR analysis and results interpretation. M.F. immunoistochemical analysis. M.S., C.V., E.B. and M.F. drafted the manuscript. A.M., M.F., V.C., E.B. and R.T.L. revised the manuscript. E.B.finalised the manuscript. All authors approved the submitted version.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-25669-1.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Khan SA, Toledano MB, Taylor-Robinson SD. Epidemiology, risk factors, and pathogenesis of cholangiocarcinoma. HPB: the official journal of the International Hepato Pancreato Biliary Association. 2008;10:77–82. doi: 10.1080/13651820801992641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saha SK, Zhu AX, Fuchs CS, Brooks GA. Forty-Year Trends in Cholangiocarcinoma Incidence in the U.S.: Intrahepatic Disease on the Rise. Oncologist. 2016;21:594–599. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaib YH, Davila JA, McGlynn K, El-Serag HB. Rising incidence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a true increase? Journal of hepatology. 2004;40:472–477. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nathan, H. et al. Trends in survival after surgery for cholangiocarcinoma: a 30-year population-based SEER database analysis. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery: official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract11, 1488–1496, discussion1496-1487, 10.1007/s11605-007-0282-0 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Mavros MN, Economopoulos KP, Alexiou VG, Pawlik TM. Treatment and Prognosis for Patients With Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA surgery. 2014;149:565–574. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.5137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Razumilava N, Gores GJ. Cholangiocarcinoma. Lancet. 2014;383:2168–2179. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61903-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jung DH, et al. Clinicopathological Features and Post-resection Prognosis of Double Primary Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. World J Surg. 2017;41:825–834. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3787-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valle J, et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;362:1273–1281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelley RK, Bardeesy N. Biliary Tract Cancers: Finding Better Ways to Lump and Split. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2588–2590. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.6953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei, M. et al. Multiple cellular origins and molecular evolution of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer letters, 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.02.038 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Jiao Y, et al. Exome sequencing identifies frequent inactivating mutations in BAP1, ARID1A and PBRM1 in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas. Nature genetics. 2013;45:1470–1473. doi: 10.1038/ng.2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan-On W, et al. Exome sequencing identifies distinct mutational patterns in liver fluke-related and non-infection-related bile duct cancers. Nature genetics. 2013;45:1474–1478. doi: 10.1038/ng.2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simbolo M, et al. Multigene mutational profiling of cholangiocarcinomas identifies actionable molecular subgroups. Oncotarget. 2014;5:2839–2852. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamura H, et al. Genomic spectra of biliary tract cancer. Nature genetics. 2015;47:1003–1010. doi: 10.1038/ng.3375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernandez-Cuesta L, et al. Frequent mutations in chromatin-remodelling genes in pulmonary carcinoids. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3518. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar A, et al. Exome sequencing identifies a spectrum of mutation frequencies in advanced and lethal prostate cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:17087–17092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108745108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simbolo M, et al. Lung neuroendocrine tumours: deep sequencing of the four World Health Organization histotypes reveals chromatin-remodelling genes as major players and a prognostic role for TERT, RB1, MEN1 and KMT2D. J Pathol. 2017;241:488–500. doi: 10.1002/path.4853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jusakul A, et al. Whole-Genome and Epigenomic Landscapes of Etiologically Distinct Subtypes of Cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:1116–1135. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrianova MA, et al. Germline PMS2 and somatic POLE exonuclease mutations cause hypermutability of the leading DNA strand in biallelic mismatch repair deficiency syndrome brain tumours. J Pathol. 2017;243:331–341. doi: 10.1002/path.4957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell BB, et al. Comprehensive Analysis of Hypermutation in Human Cancer. Cell. 2017;171:1042–1056 e1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Churi CR, et al. Mutation profiling in cholangiocarcinoma: prognostic and therapeutic implications. PloS one. 2014;9:e115383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Javle M, et al. Biliary cancer: Utility of next-generation sequencing for clinical management. Cancer. 2016;122:3838–3847. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ong CK, et al. Exome sequencing of liver fluke-associated cholangiocarcinoma. Nature genetics. 2012;44:690–693. doi: 10.1038/ng.2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soria JC, et al. Afatinib versus erlotinib as second-line treatment of patients with advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the lung (LUX-Lung 8): an open-label randomised controlled phase 3 trial. The Lancet. Oncology. 2015;16:897–907. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bria E, et al. Comprehensive molecular portrait using next generation sequencing of resected intestinal-type gastric cancer patients dichotomized according to prognosis. Scientific reports. 2016;6:22982. doi: 10.1038/srep22982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruzzenente A, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma Heterogeneity Revealed by Multigene Mutational Profiling: Clinical and Prognostic Relevance in Surgically Resected Patients. Annals of surgical oncology. 2016;23:1699–1707. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-5046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang SZ, et al. Low expression of ARID1A correlates with poor prognosis in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. World journal of gastroenterology. 2016;22:5814–5821. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i25.5814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luchini C, et al. Prognostic role and implications of mutation status of tumor suppressor gene ARID1A in cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2015;6:39088–39097. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arnold A, et al. Genome wide DNA copy number analysis in cholangiocarcinoma using high resolution molecular inversion probe single nucleotide polymorphism assay. Experimental and molecular pathology. 2015;99:344–353. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyamoto M, et al. Prognostic significance of overexpression of c-Met oncoprotein in cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:131–138. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ikenoue T, et al. A novel mouse model of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma induced by liver-specific Kras activation and Pten deletion. Scientific reports. 2016;6:23899. doi: 10.1038/srep23899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bosman, F., Carneiro, F., Hruban, R. H. & Theise, N. D. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Digestive System. 4th edn, Vol. 3 (IARC Press, 2010).

- 34.Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Annals of surgical oncology. 2010;17:1471–1474. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simbolo M, et al. DNA qualification workflow for next generation sequencing of histopathological samples. PloS one. 2013;8:e62692. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zamo A, et al. Application of microfluidic technology to the BIOMED-2 protocol for detection of B-cell clonality. The Journal of molecular diagnostics: JMD. 2012;14:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cingolani P, et al. Using Drosophila melanogaster as a Model for Genotoxic Chemical Mutational Studies with a New Program, SnpSift. Frontiers in genetics. 2012;3:35. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McLaren W, et al. Deriving the consequences of genomic variants with the Ensembl API and SNP Effect Predictor. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2069–2070. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robinson JT, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nature biotechnology. 2011;29:24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Corbo V, et al. Pancreatic endocrine tumours: mutational and immunohistochemical survey of protein kinases reveals alterations in targetable kinases in cancer cell lines and rare primaries. Annals of oncology: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2012;23:127–134. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brunelli M, et al. HER-2/neu assessment in breast cancer using the original FDA and new ASCO/CAP guideline recommendations: impact on selecting patients for herceptin therapy. American journal of clinical pathology. 2008;129:907–911. doi: 10.1309/MD79CDXN1D01E862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brunelli M, et al. Genotypic intratumoral heterogeneity in breast carcinoma with HER2/neu amplification: evaluation according to ASCO/CAP criteria. American journal of clinical pathology. 2009;131:678–682. doi: 10.1309/AJCP09VUTZWZXBMJ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolff AC, et al. Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline update. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2014;138:241–256. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0953-SA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.