Abstract

The increasing demand for nanostructured materials is mainly motivated by their key role in a wide variety of technologically relevant fields such as biomedicine, green sustainable energy or catalysis. We have succeeded to scale-up a type of gas aggregation source, called a multiple ion cluster source, for the generation of complex, ultra-pure nanoparticles made of different materials. The high production rates achieved (tens of g/day) for this kind of gas aggregation sources, and the inherent ability to control the structure of the nanoparticles in a controlled environment, make this equipment appealing for industrial purposes, a highly coveted aspect since the introduction of this type of sources. Furthermore, our innovative UHV experimental station also includes in-flight manipulation and processing capabilities by annealing, acceleration, or interaction with background gases along with in-situ characterization of the clusters and nanoparticles fabricated. As an example to demonstrate some of the capabilities of this new equipment, herein we present the fabrication of copper nanoparticles and their processing, including the controlled oxidation (from Cu0 to CuO through Cu2O, and their mixtures) at different stages in the machine.

Introduction

By reducing the dimensions of a material to the nanometer regime, new physicochemical properties emerge that lead to a wide range of novel applications1–3. Currently, a large variety of technological fields, such as catalysis4–7, sensing8,9 or biomedicine10,11 have an increased need for high throughput methods for the production of clusters and nanoparticles (NPs) with a precise control of size, shape and composition. Wet chemistry protocols meet the requirements of high throughput with relative simplicity and low cost. However, they have intrinsic limitations regarding the purity, size distribution and, for particular NP configurations, thermodynamic restrictions also exist. For an extreme control of the reaction conditions and purity of the clusters and NPs produced, gas-phase techniques working in ultra-high vacuum (UHV) present the ideal environment12, thanks to the absence of ligands5, albeit with lower throughput. Amongst these, sputter gas aggregation sources developed by Haberland and co-workers13 have become the most popular, not only due to the fraction of ionized NPs, which allows mass/charge selection14, but also to the wide variety of materials that can be sputtered15.

In order to overcome the throughput limitation, we have designed and built a scaled-up gas aggregation source. Different approaches have been developed during recent years in order to obtain large NP fluxes with gas aggregation sources16–19. In our case, the new design is based on an adjustable multi-magnetron or Multiple Ion Cluster Source (MICS)20, which incorporates three independent magnetrons inside an aggregation zone. Although the MICS has emerged as a precise tool for the controlled fabrication of complex NP architectures with adjustable chemical composition, size and structure21,22, the approach presented here represents a further step in terms of the tailored generation of controlled nanoparticles with high throughput. The new design of the scaled-up MICS is the origin of the Stardust machine, an innovative experimental station devoted to the production of large amounts of NPs, which also offers the possibility of in-flight manipulation (i.e.: gas injection at different stages, heating, accelerating,…) and in-situ characterization by electron spectroscopy techniques and thermal desorption spectroscopy.

Stardust was originally designed to simulate cosmic-dust formation and processing in the circumstellar region of evolved stars. The ultimate goal is to fabricate in the laboratory the nanoparticles that constitute the refractory part of this cosmic dust. Today with the new generation of telescopes and antennas, such as the ALMA interferometer in Chile, we start to obtain detailed information on the physical and chemical conditions that lead to the formation of this refractory dust23. Notwithstanding, the range of use of Stardust can be extended far beyond this original conception to many different fields of application in nanotechnology. Stardust offers a unique workbench to unravel the properties of individual NPs through in-flight processing and analysis.

In this article, we present a description of the technical solution adopted to build the Stardust machine and some representative results to demonstrate its capabilities. In particular, we have focused on the precise fabrication, manipulation and in-situ analysis of Cu nanoparticles. One of the most interesting processing capabilities involves the reaction with gases at different stages (or modules) in Stardust. In this respect, we have performed a controlled oxidation study of Cu NPs.

Copper-oxide NPs exhibit a different band-gap as a function of stoichiometry and therefore it is possible to tune their optical and electronic properties from metal to semiconductor. Thus, the preparation of high-quality copper-oxide NPs with a narrow size distribution are of increasing interest in fields such as solar energy conversion cells or catalysis24,25. Cu based NPs have been previously produced using gas aggregation sources, either for fundamental studies concerning the fabrication process itself26,27, or for testing new cluster sources28. However, to our knowledge, an accurate control of the Cu oxidation state through reactive sputtering using gas aggregation sources that avoid poisoning of the target has not been previously reported. Here we present a fabrication route based on a sputter gas aggregation source with controlled oxygen injection at different stages of NP formation, using the gas-processing capabilities of Stardust, which allows accurate tailoring of the degree of oxidation of the NPs, from metallic Cu through Cu2O to CuO. The results are compared with oxidation treatments performed on Cu NPs supported on highly ordered pyrolytic graphite (HOPG).

Results and Discussion

The stardust machine

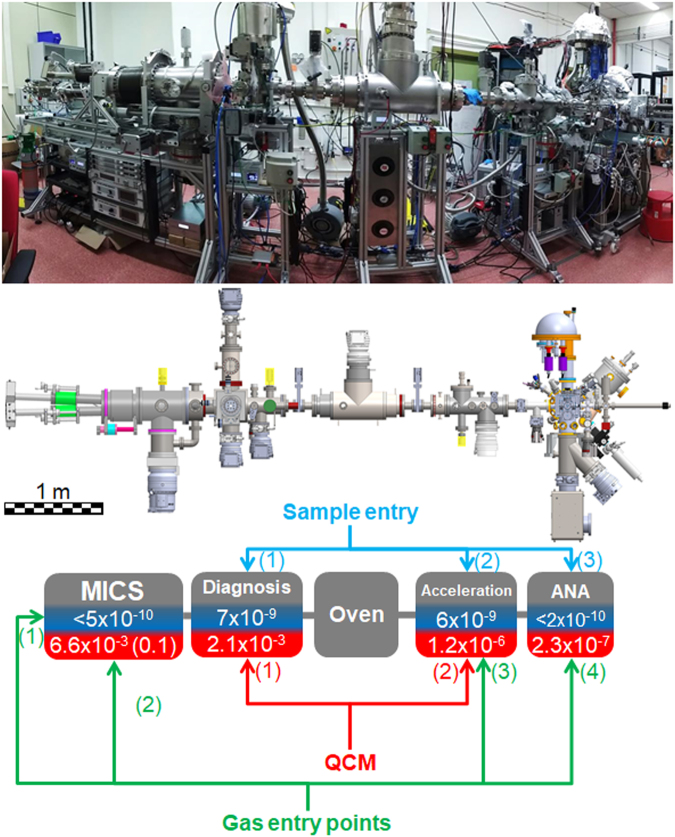

In order to provide the maximum flexibility for the fabrication, manipulation and analysis of nanoparticles, Stardust was conceived as a modular device. At present it comprises 5 different UHV modules. Figure 1 presents the global design of the equipment in one of its possible configurations.

Figure 1.

The Stardust machine, side view (photograph, top), machine schematic (middle); block diagram and scheme of the pressures, in mbar, in the system (bottom): base pressure on blue background and working pressure on red background (for ϕT = 150 sccm). The pressures indicated were measured with the gauges highlighted in yellow in the picture. In the case of the MICS module, the value in brackets corresponds to that measured inside the aggregation zone. Gas entry points (1–4) and quartz crystal microbalance position (QCM 1 and 2) are indicated.

The first and fundamental module, called the MICS module, is a sputtering based gas aggregation source devoted to cluster and NP fabrication. The presence of three completely independent magnetrons inside the aggregation chamber, allows the simultaneous use of up to three different targets for a precise generation of clusters and NPs of different sizes, composition and structure, ranging from single element particles to alloys or core-shell nanostructures, with a precise control of the stoichiometry21,22,29. A scaled-up MICS was designed in order to achieve high NP fluxes and larger NP sizes. This new device, fabricated by Oxford Applied Research Ltd. under the name MICS3, employs 3 magnetrons of 2” diameter (instead of 1” from the original design). The aggregation zone where the three magnetrons are located has been re-dimensioned and two facing path-troughs towards the exterior have been included at both sides. These new entrances can be used either for pressure measurements, plasma monitoring or for gas injection. Further information about this module is provided in Section S1 of the Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM).

The NPs produced in the MICS module can be further manipulated, analyzed or collected in other modules. The subsequent three modules are dedicated to the monitoring and modification of physical properties of the generated NPs. They are called Diagnosis, Oven and Acceleration modules.

In the Diagnosis module the NPs yield can be monitored using a quartz crystal microbalance (QCM-1 in Fig. 1). It also incorporates a fast entry port for the introduction of substrates, allowing samples to be prepared for ex-situ analysis. An electrostatic quadrupole deflector can guide the charged particles towards a quadrupole mass spectrometer. The quadrupole can be placed in line with the NP beam to perform mass filtering. In an initial configuration, it was mounted in line, but to increase throughput we consider the configuration described to be a better option. Full details of this module are given in the ESM, Section S2.

After travelling through the diagnosis chamber the NPs enter the Oven module. In their path through this module the NPs are immersed in an IR-bath, absorbing the electromagnetic radiation during their transit, which results in an increase in their temperature. Details of this module are provided in the ESM, Section S3.

The last manipulation module of Stardust is the Acceleration module, where it is possible to modify the speed and trajectory of the NPs during their travel through it using charged particle optics, and/or induce interactions with injected gases. Just before the exit of this module, a Faraday cup and a quartz crystal microbalance (QCM-2 in Fig. 1) are installed to help monitoring all processing in the chamber. A scheme of this sequence is provided in Fig. S4.1 of the ESM.

Finally, in the fifth module called ANA, in-situ analysis of the NPs can be undertaken by electron spectroscopy techniques and thermal desorption spectroscopy. A PHOIBOS 100 1D electron/ion analyzer with a one-dimensional delay line detector allows X-Ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS), Auger electron spectroscopy (AES) and low-energy ion spectroscopy (LEIS) to be performed. Thermal desorption spectroscopy (TDS) is performed using a Pfeiffer HiQuad QMG 700 with QMA 400 mass spectrometer, with a mass range of 0 to 512 amu, and a CP 400 ion counter preamplifier (Detection limit 10−15 mbar).

With the exception of the MICS module, the disposition of each module in the machine can be modified to adapt the experimental set-up to a particular scientific objective. Thus, they can be placed in the standard configuration, presented in Fig. 1, removed or placed in a different sequence. This design confers high versatility to the whole system. In the near future, an additional module called INFRA-ICE will be incorporated. This will be equipped with an infrared spectrometer and a closed-cycle helium cryostat and will further boost the characterization capabilities of Stardust allowing both the study of deposited clusters/NPs and ice-analogs using reflection and transmission FTIR spectroscopy.

Stardust includes five gas entry points (depicted in Fig. 1), three in the MICS module where the NPs are fabricated, one in the Acceleration module where the NPs are still in the gas phase and one in ANA, where the NPs are collected on a substrate. This broadens the versatility of Stardust for NP processing, not only in terms of the modification of the composition of the NPs, but also for heterogeneous catalytic processes. Gas mixing systems have been implemented to allow dosing of gases and liquid vapors (detailed information in Section S5 of the ESM).

In order to have a highly controllable and clean environment for the fabrication of NPs, it is of paramount importance to have a system base pressure that is as low as possible. Special care was taken to use stainless steel gas pipes and CF flanges. The typical base pressures in the system are indicated in Fig. 1, where it is also displayed the typical working pressures for a given sputtering gas injection of 150 sccm. The pumping details are given in the ESM, Section S6. Stardust is aligned using a theodolite in order to obtain a fine alignment of all the modules. We have not observed any important deviation of the beam induced by gravity on the particle trajectory.

Nanoparticle fabrication

Rates and size distribution

Cu NPs have been fabricated in order to test the scaling-up of the MICS as well as the processing capabilities of Stardust.

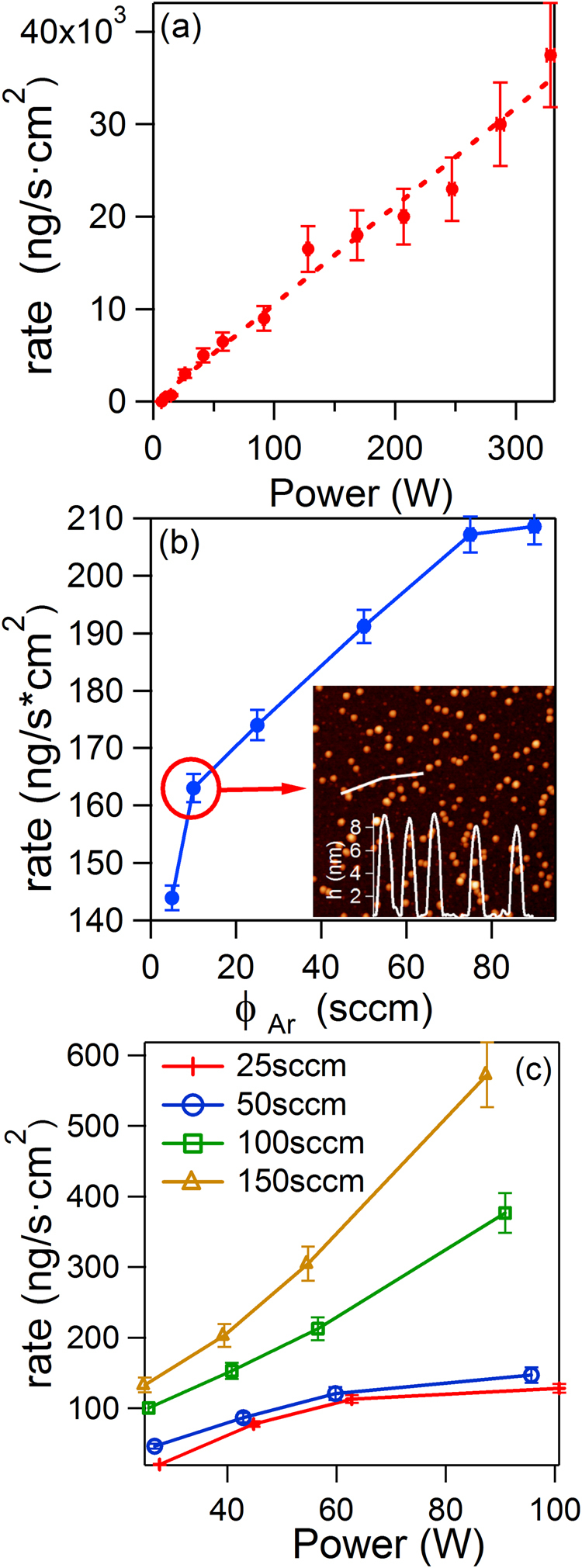

The monitoring of the NP rate generated in the MICS module was undertaken using QCM-1 located at 40 cm from the MICS exit, in the Diagnosis module (see Fig. 1). Figure 2a presents the evolution of the NP rate as a function of the power applied to the magnetron. A continuous increase in the rate with applied power can be observed. Even though these magnetrons can work up to 1000 W, we only tested up to 330 W, reaching a rate of 37.5 µg/s · cm2 measured at the beam center, which provides an indication of the high fluxes that can be achieved with this scaled-up MICS.

Figure 2.

(a) Nanoparticle rate vs. power (ϕT = 100 sccm, ϕAr = 50 sccm); (b) Evolution of the NP rate as a function of the ϕAr injected through the magnetron in use for a ϕT of 100 sccm (P = 30 W). Inset: AFM image (1 µm2) of the sample fabricated with ϕAr = 10 sccm. (c) NP rate vs. power for different ϕT in the magnetron in use (ϕAr = 10 sccm). The error bars indicate a 10% error of the QCM measurement.

Besides the well-known operational parameters from conventional sputter gas aggregation sources, such as power, aggregation length (distance of the magnetron to the exit nozzle) or Ar flux (ϕT), the MICS has some characteristic key parameters. For instance, not only is the total amount of sputtering gas injected through the three magnetrons (where ϕT = ϕ1 + ϕ2 + ϕ3) important, but also the amount of sputtering gas injected through the magnetron in use (ϕAr in this work, as only one magnetron is used)30. Figures 2b and c display two representative examples. In the first case, the monitoring of the NP rate vs. ϕAr evidenced higher rates for increasing ϕAr. The same trend was found for other ϕT values. The inset in Fig. 2b presents a representative atomic force microscopy (AFM) image of a deposit fabricated with ϕAr = 10 sccm. A narrow size distribution can be observed (8.5 nm, std. dev. 0.3 nm), taking into account that no mass filtering was used.

Figure 2c presents the evolution of the NP rate as a function of the applied power for different ϕT. In this case, for a given power, the higher the ϕT, the larger is the registered rate. It is interesting to notice that for ϕT = 100 sccm there is a linear increase in the rate with power, similar to that presented in Fig. 2a. However, this linear trend is not followed at other values of ϕT. All the trends presented in Fig. 2 are representative of particular experimental conditions. It must be considered that the evolution of the target during its lifetime, i.e.: the so-called race track formation, can cause variations in the generation of nanoparticles for the same experimental conditions31.

Optical Emission Spectroscopy in the aggregation zone

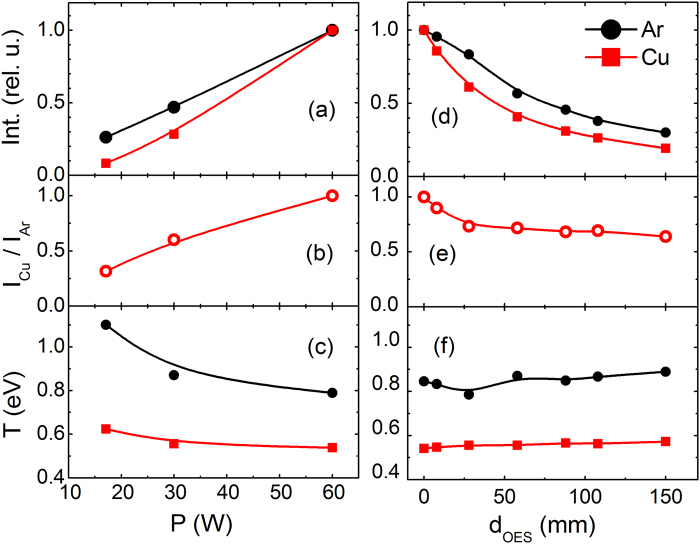

By using one of the lateral entrances of the aggregation zone (see ESM, Fig. S1) the plasma can be monitored by Optical Emission Spectroscopy (OES). The optical spectra in the visible range show lines of Ar and Cu neutral atoms. Figure 3a presents the evolution of the intensities of the 696.5 nm Ar line (IAr) and the 578.2 nm Cu line (ICu) as a function of the power applied to the magnetron. For ease of comparison, the signals have been normalized to the maximum power observed. The linear trend observed has also been found in other DC magnetron discharges32, and is attributed to the linear increase of electron density with discharge power33. The ICu/IAr ratio also increases with the applied power (Fig. 3b). This quotient is related to the ratio between the excited populations of Cu and Ar34 and indicates that the efficiency of Cu sputtering by Ar ions striking the target increases with P. These effects are in accordance with the increase in NP deposition rate with power shown in Fig. 2. Figure 3c illustrates how the excitation temperatures for Ar and Cu, extracted from Boltzmann plots, decrease with power from 1.10 to 0.78 eV for Ar and from 0.62 to 0.50 eV for Cu over the interval investigated. This behavior has been ascribed to the increase of the sputtering yield of Cu by Ar ions, which causes in turn a loss of electron energy in the magnetized region by excitation and ionization collisions with the metal atoms35,36.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the experimental Ar (λ = 696.5 nm) and Cu (λ = 578.2 nm) line intensities (a,d), the ratio between both intensities ICu/IAr (b,e) and the Ar and Cu excitation temperatures (c,f), depicted as a function of the magnetron power at a fix distance (dOES = 58 mm) (a–c), and as a function of the magnetron distance, dOES, at a constant power (P = 30 W) (d–f). Lines serve as guides.

Figure 3d presents the evolution of IAr and ICu as a function of the distance between the magnetron and the line of sight of the optical spectrometer (dOES). Both intensities decrease with increasing dOES due, most likely, to the fall in electron density further away from the magnetron37. The evolution of the ratio of the normalized intensities ICu/IAr is presented in Fig. 3e. Over the first 30 mm this ratio drops by ∼30% suggesting an initial dilution of the sputtered Cu atoms with increasing distance from the Cu target. Aggregation processes could also contribute to the observed drop. Beyond this point, the ICu/IAr ratio shows only a slow decline. The excitation temperatures of Ar and Cu as a function of dOES are analyzed in Fig. 4f. In both cases the temperature is approximately constant (variations < 10%) over the range of distances studied. This observation indicates that the electron energy distribution, which essentially determines the population of the excited states leading to the observed emissions, should not vary appreciably over the same distance interval. In fact, the electron temperatures measured by Langmuir probes in conventional magnetron plasmas33,38, have been found to remain constant for a relatively large distance from the magnetron.

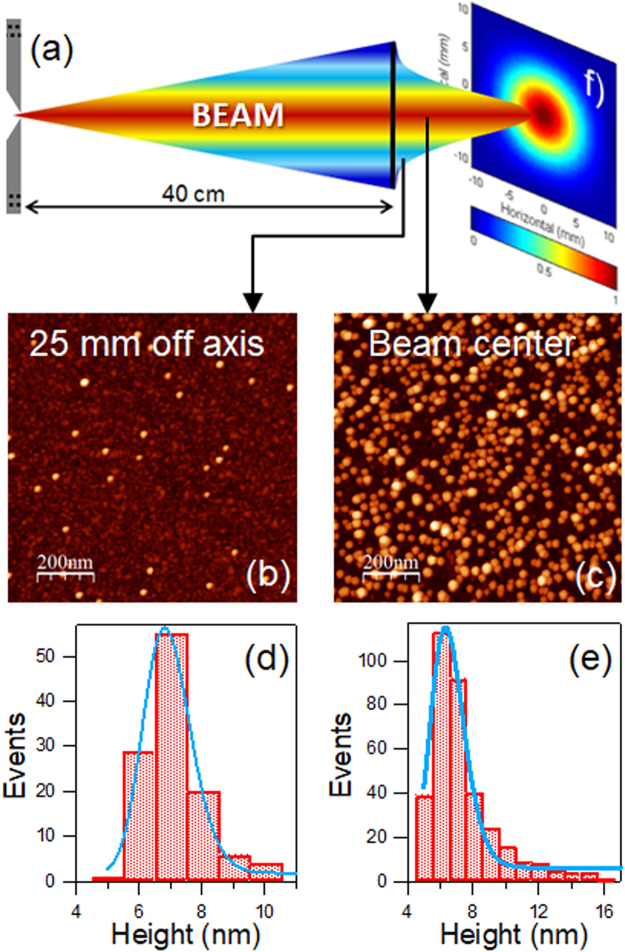

Figure 4.

(a) Illustration of the beam divergence at the exit of the MICS with the Gaussian profile measured with QCM-1. AFM images of nanoparticles collected (b) at 25 mm off axis and (c) at the beam center. Log-normal distribution of the height on the nanoparticles collected (d) at 25 mm off axis, and (e) at the beam center. (f) Beam shape derived from the optical absorption measured in the mid-IR region of nanoparticles deposited on a glass slide at 740 mm from the MICS exit.

Beam characterization

The beam shape after the expansion out of the MICS module was evaluated with the QCM-1 mounted on a z-translator perpendicular to the NP beam. The results showed a Gaussian beam shape with a divergence of around ±5° under the experimental conditions tested (Fig. 4a). The homogeneity of the NPs produced with the MICS was analyzed both at a position 25 mm off-axis (Fig. 4b) and at the beam center (Fig. 4c) by AFM, on samples deposited through the sample entry-1 (located in front of QCM-1). It can be observed that for the same deposition time of 2 s the rate clearly decreases off-axis. The mean nanoparticle size follows a typical log-normal distribution, with the maximum at 6.8 nm when measured off-axis (Fig. 4d) and at 6.3 nm in the beam center (Fig. 4e). The presence of an increased number of larger NPs (tail of the log-normal) when measured at the beam center probably arises from the fact that, as can be observed in the AFM images, the NP density is much higher in this sample and some particles could be found on top of others. Moreover, in the AFM images the presence of small features can be observed, which might be confused with small nanoparticles. However, an AFM analysis of the as-received SiOx substrate shows that they are induced by the surface roughness as these features are present prior to deposition of NPs. Additional information on this issue is provided in Section 7 of the ESM.

For an improved characterization of the beam shape, we deposited NPs on glass slides and performed subsequent ex-situ measurements of the optical absorption in the mid-IR region. Figure 4f (right-hand side of Fig. 4a) presents the resulting homogeneous 2D-gaussian profile.

Manipulation of the NP beam is possible using the acceleration module (see ESM, Fig. S4.1). By placing QCM-2 in the beam axis and the faraday-cup 20 mm off-axis, when a voltage is applied to the second set of deflection plates, a decrease in the NP yield of about 60–80% was registered in QCM-2. This means that for the experimental conditions employed (P = 30 W; ϕT = 150 sccm; ϕAr = 10 sccm; aggregation length 374 mm), around 60–80% of the mass of the Cu NPs produced in the MICS module is carried by charged particles. From the sign of the current detected with the Faraday cup, one can determine that they are mostly negatively charged. Moreover, as the ionizer at the entrance of the acceleration module can be operated to further ionize neutral species, it is possible to further increase this percentage (see ESM, Fig. S4.2). The use of the grid located at the beginning of this module increase in the NP yield of between 2.5 and 3.5 times measured at QCM-2. Finally, by applying −180 V to the Einzel-lens after the grid, an increase of more than 50% in the NP yield was also observed. It is worth mentioning that, although the fraction of Cu charged NPs measured could be as high as 80%, only a very small number of charged atoms are involved. Indeed, considering that the NPs are singly charged and the average diameter of the NPs is 7 nm in these experiments, the ratio of charged to neutral atoms is of the order of 10−5 20.

The average speed of the charged Cu NPs was determined by applying a trigger voltage on the first set of deflection plates at the entrance of the acceleration module and measuring the time delay on the Faraday cup. An average speed of 140 ± 20 m/s was found for Cu NPs (see ESM, Fig. S4.3). This value corresponds to kinetic energies of the order of a few meV/atom, well within the range for soft landing, ensuring no collision-induced deformation upon collection on a substrate, as expected when using sputter gas aggregation sources39.

Controlling The Stoichiometry Of Cu-Oxide Nanoparticles

The high fluxes of NPs generated with the MICS module make possible in-situ characterization in the ANA module, at 4.5 m from the MICS exit. In order to evaluate the effect of gas injection (O2 in this case) using the gas mixing system (see ESM, Section S5) at different parts of the Stardust machine, Cu NPs deposits were obtained on HOPG substrates located in the ANA module for further XPS analysis.

Three different experiments were performed: firstly, oxidation of Cu NPs supported on HOPG in the ANA module (through gas entry-4); secondly, oxidation through the new entrances performed in the aggregation zone (gas entry-2); thirdly, oxidation of the Cu NPs from behind the magnetrons (gas entry-1).

A power of 40 W was applied to the Cu magnetron without O2 injection and was typically controlled in current (0.15 A). The O2 injection in the aggregation zone led to an increase in the discharge voltage, an effect that has been previously reported for reactive sputtering in gas aggregation sources40.

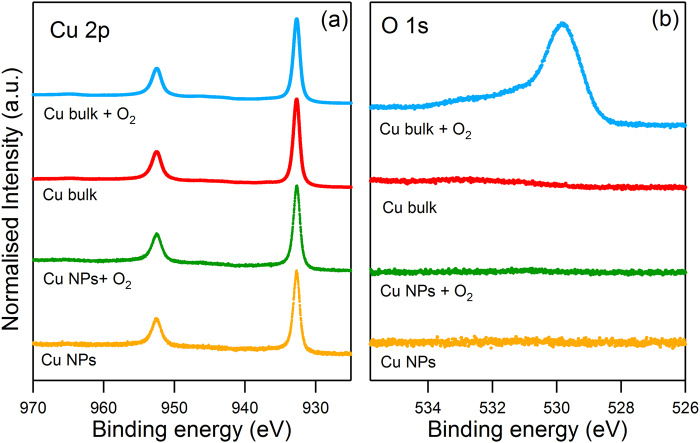

For the first experiment, Cu NPs were deposited on HOPG in the ANA chamber. Figure 5 shows (a) the Cu 2p and (b) the O 1 s core level peaks for this sample (yellow line). The Cu 2p3/2 peak at a binding energy (BE) of 932.7 eV, typical of metallic Cu41 and the absence of a peak in the O 1 s core level peak, is a clear indication of the cleanliness of the fabrication process in Stardust. The base pressure below 5 × 10−10 mbar is important to avoid any possible oxidation from impurities42. After O2 exposure (13500 L) of these Cu NPs (green spectra in Fig. 5), no evidence of changes in either the Cu 2p or in the O 1 s line shape with respect to the as-deposited NPs was observed, indicating that oxygen does not bind to or react with the NPs. No traces of oxygen were found, even when the O2 treatment was performed at 300 °C.

Figure 5.

(a) Cu 2p and (b) O 1 s core level XPS spectra of Cu NPs as-deposited (yellow), after O2 treatment in ANA module (green), UHV cleaned Cu bulk (red) and Cu bulk after the same O2 treatment (blue).

For comparative purposes, a reference Cu sample (hereafter denominated Cu bulk) was also measured under the same conditions. After cleaning the sample, the XPS spectra presented an intense Cu 2p peak and the clear absence of oxygen contamination (red spectrum in Fig. 5). By performing the same O2 injection in the ANA chamber (13500 L) (blue spectrum in Fig. 5) the emergence of a peak in the O 1 s core level was clearly observed, with a maximum at 529.8 eV and without apparent changes in the Cu 2p peak. Both facts reveal the formation of Cu2O43. This evidenced the higher chemical inertness of Cu NPs (NP mean size: 7 nm diameter) in comparison to Cu bulk, where a high oxygen dose does not succeed in forming any oxide or adsorbed species.

After the experimental confirmation of the lack of oxidation in the case of Cu NPs compared to Cu bulk in these experimental conditions, a second oxidation experiment was carried out introducing O2 in the aggregation zone through gas entry-2. The distance between the magnetron and the gas entry-2 was 180 mm for these experiments. Different ϕO2 fluxes ranging from 0.1 to 21.5 sccm with respect to a ϕT = 150 sccm were tested in order to evaluate, firstly, the possibility to oxidize the NPs from this new entrance and, secondly, the ability to control the stoichiometry of the oxides generated.

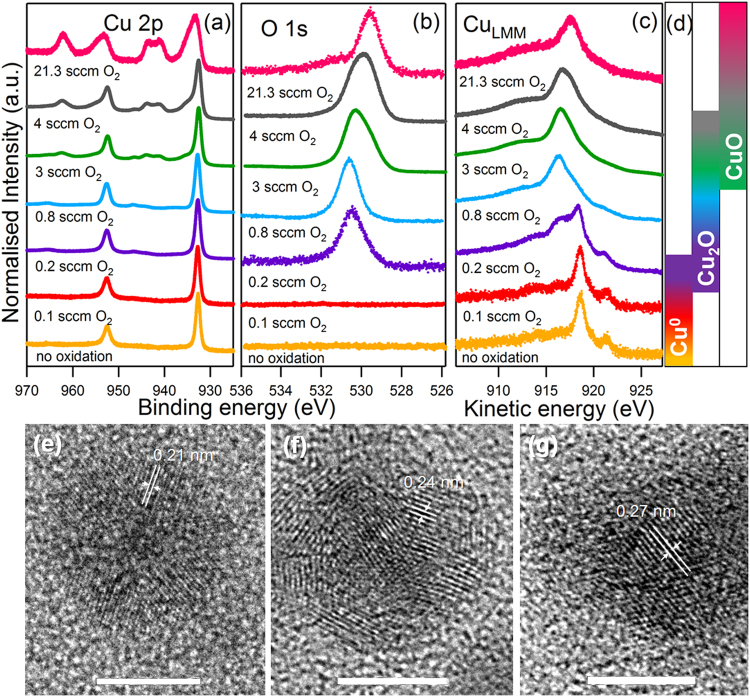

Figure 6(a–c) displays the line-shape of the Cu 2p (a), O 1 s (b) and CuLMM (c) of Cu NPs fabricated with different ϕO2 in the aggregation zone. The reference Cu0 NPs discussed in the previous figure (yellow curve) is also included in Fig. 6 for ease of comparison. The injection of 0.1 sccm O2 in the aggregation zone (red curve) does not seem to induce any detectable change in the Cu NPs in comparison to Cu0 NPs. However, higher values of ϕO2 have a progressive influence on the final composition of the NPs. The value of 0.2 sccm O2 (violet curve) constitutes the threshold ϕO2 to initiate oxidization of the Cu NPs fabricated under the experimental conditions employed. Even though the Cu 2p core level has the same shape as Cu0 NPs, as previously discussed in Fig. 5, the presence of a peak in the O 1 s core level evidenced the formation of Cu2O. The same was observed for a flux of 0.8 sccm (blue curve), where only a slight shift of 0.1 eV towards higher BE was registered in the O 1 s peak in comparison to the 0.2 sccm treatment. The analysis of the CuLMM peak (Fig. 6c) showed how, whilst the treatment at 0.1 sccm O2 presents the same Auger shape as the Cu0 NPs, higher O2 fluxes induce a change in the CuLMM peak. For a flux of 0.8 sccm, the shape of the Auger peak corresponds to Cu2O44, whereas the treatment at 0.2 sccm represents an intermediate situation between Cu0 and Cu2O, suggesting a partial oxidation of the NPs.

Figure 6.

(a) Cu 2p, (b) O 1 s core levels and (c) CuLMM Auger peak of Cu NPs after different O2 treatments using gas entry point −2. (d) Diagram of the formation and coexistence of the Cu species with ϕO2. TEM images of (e) Cu0, (f) Cu2O and (g) CuO nanoparticles. Scale bar: 5 nm.

For increasing values of ϕO2, there is a progressive change in the shape of the Cu 2p core level, with a shoulder in the main peak at 934.5 eV and new peaks at 941.3 eV and 943.9 eV. These observations are characteristic of CuO43,44 that, for ϕO2 of around 3–4 sccm coexists with Cu2O. There is also evidence for CuO formation in the O 1 s core level, with the presence of a component at 529.7 eV and a shoulder at higher KE in the CuLMM peak. Total Cu oxidation to CuO is achieved using a ϕO2 of 21.3 sccm.

This ability to control the oxidation state of the NPs is confirmed by the structural analysis obtained by high resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR TEM) images. Figure 6e–g shows NPs fabricated (e) in absence of O2, (f) 0.5 sccm O2 and (g) 21.3 sccm O2. The respective interplanar distances indicated in the figure are 0.21, 0.24 and 0.27 nm in accordance to the lattice spacing of (111) Cu45, (111) Cu2O46 and (110) CuO47, respectively. These images show the crystalline nature of both, metallic and oxide NPs. Interestingly, in the case of the Cu0 image (Fig. 6e), we do not find any appreciable oxidation of the nanoparticle surface induced by molecular oxygen after the ex-situ analysis, in good agreement with the XPS results after the oxidation treatment with molecular oxygen in the analysis chamber (Fig. 5).

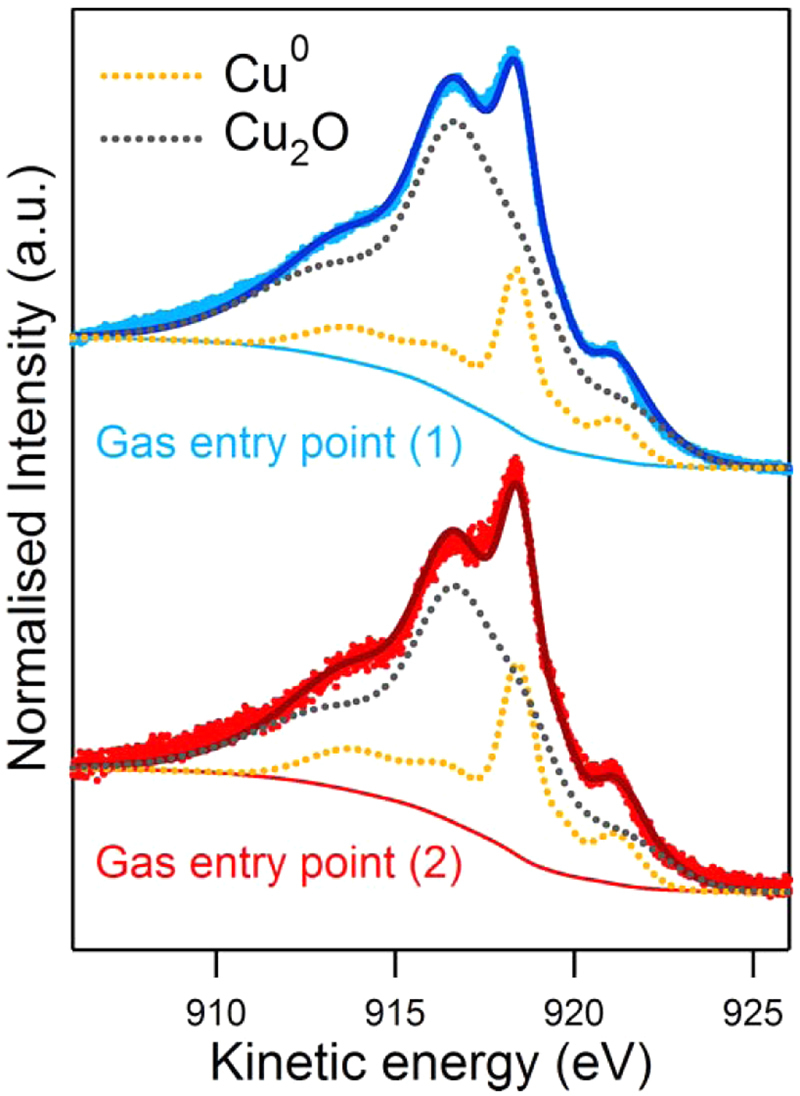

To evaluate whether any difference exists between injection of the reactive gas through gas entries -1 or -2, we injected the threshold ϕ of 0.2 sccm through gas entry-1 (behind the magnetron). This resulted in no significant differences in the Cu 2p and O 1 s core level peaks. Only small changes were observed in the CuLMM peak (Fig. 7) which indicated a more effective oxidation when introducing the O2 from the rear side of the magnetron (77% Cu2O in comparison to 70% Cu2O through gas entry-2).

Figure 7.

Comparison of the CuLMM peak after O2 injection through gas entry points 1 and 2.

It is well-known that oxygen inclusion during fabrication of metal NPs with gas aggregation sources strongly influences the formation process. For metals like Cu, Ti, Al or W, the presence of small amounts of oxygen lead to an increase of the deposition rate40,48–50. However, in those cases there is a critical threshold above which this effect vanished due to poisoning of the target, leading to a drastic reduction in the production rate. The results presented here are in contrast with the existing literature since, for all ϕO2 tested, the rates monitored with the QCM are much higher than those in the absence of O2 (no values are shown as the rates registered were too high to properly be measured them without causing a crystal failure of the QCM). The differences observed may arise from the manner in which the O2 is injected. Reactive sputtering in gas aggregation sources is usually carried out by using a mixture of O2 and Ar as sputtering gas. In our case, the entrance for the sputtering gas is left only for Ar, whilst O2 is injected in all cases at a distance that seems to be far enough away to avoid target poisoning. However, it is important to point out that the discharge voltages always increased after O2 injection, which is indicative of oxygen involvement in the plasma.

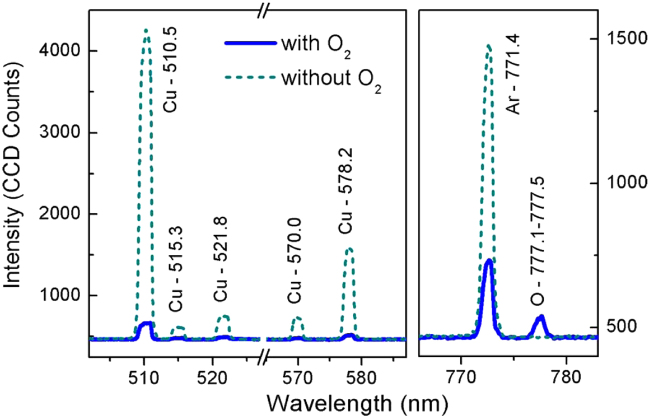

In order to evaluate to what extent oxygen can be involved in the sputtering process, OES was employed and spectra were recorded during the fabrication of NPs with ϕO2 = 0 sccm and ϕO2 = 21.3 sccm through gas entry-2. For these measurements, we placed the magnetron closer to the line-of sight of the optical spectrometer (the same as gas entry-2, dOES = 0 mm) to improve the signal-to-noise ratio. This configuration could slightly overestimate the influence of O2 with respect to the oxidation experiments discussed in Fig. 6.

The comparison of both spectra, with and without O2 (Fig. 8), revealed the appearance of some lines characteristic of atomic oxygen around 777 nm when O2 was introduced in the aggregation zone, meaning that dissociation of O2 occurs during the process. At the same time, the lines of atomic Cu almost disappeared and the intensity of Ar lines decreased significantly. Similar trends have been previously observed for metal oxide nanoparticles formation using this technique50. However, in these cases, the detection of O atoms was correlated to a drastic decrease in the deposition rate, a phenomenon that was not observed here. The formation of Cu oxides, as detected in the XPS analysis, is favored by the presence of free O atoms, which at the same time explains the significant decrease in the Cu emission. Additionally, the consumption of part of the power applied to the magnetron in the dissociation of O2 can also contribute to the reduction of Cu emission and the decrease of Ar intensity.

Figure 8.

Emission spectra of the magnetron plasma showing the intensity decrease of Cu and Ar lines, and the appearance of excited atomic oxygen, when O2 was added through gas entry-2.

Summary

In this work, we present the Stardust machine, an innovative UHV experimental station for the production of controlled NPs, with in-flight manipulation and processing capabilities along with in-situ analysis of the NPs. The new design of the scaled-up MICS has successfully reached the goal of a high-throughput fabrication of NPs using a sputter gas aggregation source. From the results presented here, deposition rates of 114.5 µg/s·cm2 integrated over the Gaussian beam shape were obtained in the case of Cu NPs using only one magnetron operated under conservative fabrication conditions, which correspond to around 10 g/day. Considering that the power applied can be three times higher than the highest power tested in this work, and higher efficiencies can be achieved using other combinations of ϕT and ϕAr, this new design represent a significant step forward towards industrial implementation of gas aggregation sources15,16,51, for applications with special requirements such as controlled purity, size distribution, stoichiometry and structure. These nanoparticles could be dispersed when deposited on low-interacting surfaces, as graphite. Different approaches have been carried out during the last years in order to disperse these high-quality nanoparticles in liquid media for applications as biomedicine10,11. Some of them involve the co-deposition of water vapor for the formation of ice52 or in-flight plasma polymer coating53.

A homogeneous 2D Gaussian shape beam with a narrow size distribution of the NPs is achieved without any filtering of the NPs (mass/charge selection). The ratio ions/neutrals typically range from 0.6 to 0.8, the Cu NPs being negatively charged. Taking advantage of some of the capabilities for in-situ manipulation, we have proven that the use of the ionizer on the Acceleration module increases this percentage of charged NPs. Furthermore, in these conditions the use of the grid and the Einzel lens increase the NP rate more than a 50%, thanks to the acceleration and focusing effect. These tools would lead as well to an increase in the NP rates discussed above.

Gas injection at different stages of Stardust evidenced differences depending on the gas entry point used. This versatility opens the route to reactions with gases at different stages of the formation of NPs, during their flight along Stardust or supported on substrates. Here, using the oxidation of Cu NPs as a showcase, an exquisite control of the stoichiometry of the resulting NPs was achieved when the oxygen is injected in the aggregation chamber (during NP formation). On the contrary, once the Cu NPs are supported on HOPG, it is not possible to oxidize the Cu NPs in the experimental conditions tested.

Finnaly, with the design and construction of Stardust, we have assembled several techniques that combine the fine control of NP fabrication with high throughputs, in-flight manipulation and in-situ characterization. The result is a unique workbench not only for creating analogues of stardust particles in the laboratory, but also for basic research including in-situ studies of fundamental properties of supported and non-supported NPs. At the same time, the high throughputs already achieved with this new MICS design open up the use of this machine for applied studies, such as catalysis, and further applications in nanotechnology.

Methods

Nanoparticle fabrication

Nanoparticles are fabricated with a scaled-up MICS working in UHV (see ESM, Section S1). For the experiments presented in this work, only one of the three magnetrons was used. This magnetron was loaded with a copper target of 99.99% purity, 2” diameter and 4 mm thickness. The results presented in this work were obtained with a nozzle of 9 mm and a diaphragm of 12 mm.

Different total Ar fluxes (ϕT) were used for the experiments, ranging from 25 to 150 sccm. ϕT corresponds to the sum of the Ar injected through each of the three magnetrons (ϕ1, ϕ2 and ϕ3), even if only one of them is in use. Typical working power was 30 W and the typical aggregation length (distance between the magnetron and the exit nozzle) was 374 mm. The substrates employed for collecting the NPs are boron-doped Si(100) with its native oxide for AFM analysis and HOPG for XPS analysis.

For the gas entry tests at different stages in the Stardust machine, extra-pure O2 (99.999%) was used. The gas is injected using the gas mixing system described in Section S5 of the ESM. Three different experiments were performed. One consisted in the oxidation of Cu NPs supported on HOPG at a pressure of 1 × 10−5 mbar O2 for 30 min, which represents about 13500 Langmuir (1Langmuir, L = 10−6 mbar·sec). This experiment was carried out in ANA module with the gate valve, which connects this module to the rest of Stardust, closed. The other oxidation treatments were carried out during the NPs during formation. In these cases the oxygen flux ϕO2 varied from 0 to 21.3 sccm. For all oxidation tests, the Ar flux was ϕT = 10 + 70 + 70 = 150 sccm, with 10 sccm corresponding to the Ar injected through the magnetron in use (ϕAr). The aggregation length was 374 mm and the deposition time 1 min.

Nanoparticle characterization

Optical emission spectroscopy (OES)

The light emitted by the plasma of the Cu target of the magnetron placed closer to the window through which the OES measurements were taken (experimental conditions: P = 30 W, ϕT = 70 sccm, ϕAr = 20 sccm) was analyzed by optical emission spectroscopy (OES) using a grating spectrometer (Ocean Optics, model QE65000) with a 300 grooves/mm grating, a cooled linear CCD-array detector (Hamamatsu S7031-1006) and an optical fiber (QP600-2-SR-BX) coupled to the 25 μm input slit of the spectrometer. The spectral range of the instrument is 200–980 nm, with 0.8 nm spectral resolution. The relative spectral sensitivity, with which the measured intensities were corrected, was calibrated using a reference standard lamp. Plasma emission was collected through an optical window installed in one of the additional entrances to the aggregation zone of the MICS chamber. The axis of the optical system was perpendicular to the discharge axis, and the diameter of the light observation cone in the discharge region did not exceed 1 cm. To estimate the excitation temperatures by means of Boltzmann plots, Ar emission lines were studied in the 675–978 nm spectral interval, which correspond to emissions from 4p, 4d and 5s upper levels, with energies between 12.9 eV and 15 eV; Cu lines were studied in the 465–580 nm range, corresponding to transitions from 4p, 4d and 5s upper levels, with energies between 3.8 eV and 7.7 eV. Energy levels and transition probabilities were retrieved from the NIST Database54.

The measurements during O2 injection were performed for the experimental conditions of: ϕT = 150 sccm; ϕAr = 10 sccm; ϕO2 = 21.3 sccm and the magnetron was placed in the line of sight of the optical spectrometer and the O2 injection took place through the same orifice.

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy

XPS measurements were carried out in-situ in the Analysis chamber using a PHOIBOS 100 1D electron/ion analyzer with a 1-dimensional delay line detector and a monochromatic Al Kα anode (1486.6 eV). The NPs were deposited for this analysis on freshly cleaved HOPG annealed overnight at 550 °C. The Cu 2p, O 1s core levels and CuLMM were recorded with a pass energy of 15 eV and a step of 10 meV. The binding energy (BE) scale was calibrated with respect to the C 1s core level peak at 284.5 eV in the case of Cu NPs and at 932.7 eV in the case of the Cu bulk reference sample.

Cleaning of Cu bulk (used as reference sample) was performed by hot sputtering at 580 °C for 30 min using a pAr = 5.0 × 10−6 mbar, 1.5 kV and 12.4 µA.

Atomic Force Microscopy

Nanoparticles were deposited on Si(100) wafers in order to perform ex-situ characterization by Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM). These substrates present a very low surface roughness, thus allowing a correct height characterization of the deposited NPs. The height and diameter of the NPs are assumed to be equal since the NPs soft-land on the substrates6. AFM measurements were performed using the Cervantes AFM System equipped with the Dulcinea electronics from Nanotec Electronica S.L. All images were recorded and analyzed using WSxM software55.

Infrared absorption

Ex-situ measurements of the optical absorption in the mid-IR region were carried out by depositing Cu NPs on glass slides. The measurements were carried out using a globar as IR source and focusing the IR beam down to (1.9 × 1.6) mm2 (Horiz. × Vert.). The voltage on a liquid nitrogen cooled MCT detector was monitored while scanning the sample using the oversampling technique.

Transmission electron microscopy

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) micrographs were recorded using a TEM/STEM (JEOL 2100F) microscope operating at 200 kV. Amorphous carbon-coated TEM grids were employed for deposition of NPs and subsequent TEM analysis and the images recorded ex-situ.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the European Union [grant number ERC-2013-SyG 610256 NANOCOSMOS]; the Spanish MINECO [grant numbers MAT2017-85089-C2-1-R, MAT2014-54231-C4-1-P, MAT2014-54231-C4-4-P, MAT2014-59772-C2-2-P, FIS2016-77578-R, FIS2013-48087-C2-1P, FIS2016-77726-C3-1P and CSIC13-4E-1775]. The authors would also like to thank Miguel Cañas, Javier Pérez and José Flores from the ICMM mechanical workshop for their invaluable help.

Author Contributions

J.C., C.J. and J.A.M.-G. had the original idea. L.M., K.L., G.S., J.M.S., V.J.H., I.T., G.J.E., J.C., Y.H., and J.A.M.-G. designed the experimental setup. L.M., K.L. and G.S. made the experiments and their analysis. R.J.P., V.J.H. and I.T. made the OES measurements. L.M. and J.A.M.-G. wrote the paper with contributions from all authors. All authors contributed to the discussions of the results and the revision of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-25472-y.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ferrando R, Jellinek J, Johnston RL. Nanoalloys: From Theory to Applications of Alloy Clusters and Nanoparticles. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:846–904. doi: 10.1021/cr040090g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grammatikopoulos P, Steinhauer S, Vernieres J, Singh V, Sowwan M. Nanoparticle design by gas-phase synthesis. Adv. Phys. X. 2016;1:81–100. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liz-Marzán LMN. Formation and color. Mater. Today. 2004;7:26–31. doi: 10.1016/S1369-7021(04)00080-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gawande MB, et al. Core-shell nanoparticles: synthesis and applications in catalysis and electrocatalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:7540–7590. doi: 10.1039/C5CS00343A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellis PR, et al. The cluster beam route to model catalysts and beyond. Faraday Discuss. 2016;188:39–56. doi: 10.1039/C5FD00178A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson GE, Colby R, Engelhard M, Moon D, Laskin J. Soft landing of bare PtRu nanoparticles for electrochemical reduction of oxygen. Nanoscale. 2015;7:12379–12391. doi: 10.1039/C5NR03154K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laskin J, Johnson GE, Prabhakaran V. Soft Landing of Complex Ions for Studies in Catalysis and Energy Storage. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2016;120:23305–23322. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b06497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liz-Marzán LM. Tailoring surface plasmons through the morphology and assembly of metal nanoparticles. Langmuir. 2006;22:32–41. doi: 10.1021/la0513353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodríguez-Lorenzo L, Álvarez-Puebla RA, de Abajo FJG, Liz-Marzán LM. Surface Enhanced Raman Scattering Using Star-Shaped Gold Colloidal Nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2010;114:7336–7340. doi: 10.1021/jp909253w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dreaden EC, Alkilany AM, Huang X, Murphy CJ, El-Sayed MA. The golden age: gold nanoparticles for biomedicine. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:2740. doi: 10.1039/C1CS15237H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Z, Barnes JC, Bosoy A, Stoddart JF, Zink JI. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles in biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:2590. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15246g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blackman, J. Handbook of Metal Physics. Volume 5:Metallic Nanoparticles. (Elsevier, 2009).

- 13.Haberland H, Karrais M, Mall M. A new type of cluster and cluster ion source. Zeitschrift für Phys. D Atoms, Mol. Clust. 1991;20:413–415. doi: 10.1007/BF01544025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker SH, et al. The construction of a gas aggregation source for the preparation of size-selected nanoscale transition metal clusters. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2000;71:3178. doi: 10.1063/1.1304868. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wegner K, Piseri P, Tafreshi HV, Milani P. Cluster beam deposition: a tool for nanoscale science and technology. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 39 R439 J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2006;39:439–459. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/39/22/R02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palmer RE, Cao L, Yin F. Note: Proof of principle of a new type of cluster beam source with potential for scale-up. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2016;87:46103. doi: 10.1063/1.4947229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piseri P, Podestà A, Barborini E, Milani P. Production and characterization of highly intense and collimated cluster beams by inertial focusing in supersonic expansions. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2001;72:2261–2267. doi: 10.1063/1.1361082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stein M, Kruis FE. Optimization of a transferred arc reactor for metal nanoparticle synthesis. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2016;18:258. doi: 10.1007/s11051-016-3559-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polonskyi, O. et al. Huge increase in gas phase nanoparticle generation by pulsed direct current sputtering in a reactive gas admixture. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103 (2013).

- 20.Huttel, Y. Gas-phase synthesis of nanoparticles. At http://eu.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-3527340602.html (WILEY‐VCH Verlag, 2017).

- 21.Martínez L, et al. Generation of nanoparticles with adjustable size and controlled stoichiometry: Recent advances. Langmuir. 2012;28:11241–11249. doi: 10.1021/la3022134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Llamosa D, et al. The Ultimate Step Towards a Tailored Engineering of Core@Shell and Core@Shell@Shell Nanoparticles. Nanoscale. 2014;6:13483–13486. doi: 10.1039/C4NR02913E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cernicharo J, et al. Unveiling the Dust Nucleation Zone of Irc + 10216 With Alma. Astrophys. J. 2013;778:L25. doi: 10.1088/2041-8205/778/2/L25. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gawande MB, et al. Cu and Cu-Based Nanoparticles: Synthesis and Applications in Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:3722–3811. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yin M, et al. Copper Oxide Nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:9506–9511. doi: 10.1021/ja050006u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blažek J, et al. Charging of nanoparticles in stationary plasma in a gas aggregation cluster source. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2015;48:415202. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/48/41/415202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koten MA, Voeller SA, Patterson MM, Shield JE. In situ measurements of plasma properties during gas-condensation of Cu nanoparticles. J. Appl. Phys. 2016;119:114306. doi: 10.1063/1.4943630. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Majumdar A, et al. Development of metal nanocluster ion source based on dc magnetron plasma sputtering at room temperature. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2009;80:95103. doi: 10.1063/1.3213612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayoral A, Llamosa D, Huttel Y. A novel Co@Au structure formed in bimetallic core@shell nanoparticles. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:8442–8445. doi: 10.1039/C5CC00774G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruano M, Martínez L, Huttel Y. Investigation of the Working Parameters of a Single Magnetron of a Multiple Ion Cluster Source: Determination of the Relative Nanoparticles. Dataset Pap. Sci. 2013;2013:8. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ganeva M, Pipa AV, Hippler R. The influence of target erosion on the mass spectra of clusters formed in the planar DC magnetron sputtering source. Surf. Coatings Technol. 2012;213:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2012.10.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Debal F, et al. Analysis of DC magnetron discharges in Ar- gas mixtures. Comparison of a collisional-radiative model with optical emission spectroscopy. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 1998;7:219–229. doi: 10.1088/0963-0252/7/2/016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bretagne J, et al. Fundamental aspects in non-reactive and reactive magnetron discharges. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2003;12:S33–S42. doi: 10.1088/0963-0252/12/4/318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Posada J, Jubault M, Bousquet A, Tomasella E, Lincot D. In-situ optical emission spectroscopy for a better control of hybrid sputtering/evaporation process for the deposition of Cu(In,Ga)Se2 layers. Thin Solid Films. 2015;582:279–283. doi: 10.1016/j.tsf.2014.09.072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vašina P, et al. Experimental study of a pre-ionized high power pulsed magnetron discharge. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2007;16:501–510. doi: 10.1088/0963-0252/16/3/009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loch DAL, Gonzalvo YA, Ehiasarian AP. Plasma analysis of inductively coupled impulse sputtering of Cu, Ti and Ni. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2017;26:65012. doi: 10.1088/1361-6595/aa6f79. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Debal F, Wautelet M, Bretagne J, Dauchot JP, Hecq M. Spatially-resolved spectroscopic optical emission of dc-magnetron sputtering discharges in argon-nitrogen gas mixtures. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2000;9:152–160. doi: 10.1088/0963-0252/9/2/307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bradley JW. The plasma properties adjacent to the target in a magnetron sputtering source. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 1996;5:622–631. doi: 10.1088/0963-0252/5/4/003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson GE, Colby R, Laskin J. Soft landing of bare nanoparticles with controlled size, composition, and morphology. Nanoscale. 2015;7:3491–3503. doi: 10.1039/C4NR06758D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marek A, Valter J, Kadlec S, Vyskočil J. Gas aggregation nanocluster source - Reactive sputter deposition of copper and titanium nanoclusters. Surf. Coatings Technol. 2011;205:573–576. doi: 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2010.12.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wagner, C. D. et al. Handbook of X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy. Surface And Interface Analysis3 (1979).

- 42.ten Brink GH, Krishnan G, Kooi BJ, Palasantzas G. Copper nanoparticle formation in a reducing gas environment. J. Appl. Phys. 2014;116:104302. doi: 10.1063/1.4895483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ghijsen J, et al. Electronic structure of Cu2O and CuO. Phys. Rev. B. 1988;38:11322–11330. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.38.11322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poulston S, Parlett PM, Stone P, Bowker M. Surface Oxidation and Reduction of CuO and Cu2O Studied Using XPS and XAES. Surf. Interface Anal. 1996;24:811–820. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9918(199611)24:12<811::AID-SIA191>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hung LL, Tsung CK, Huang W, Yang P. Room-temperature formation of hollow Cu2O nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 2010;22:1910–1914. doi: 10.1002/adma.200903947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sui, Y. et al. Synthesis of cu2o nanoframes and nanocages by selective oxidative etching at room temperature. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 49, 4282–4285 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Su D, Xie X, Dou S, Wang G. CuO single crystal with exposed {001} facets-A highly efficient material for gas sensing and Li-ion battery applications. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:1–9. doi: 10.1038/srep05753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peter T, et al. Influence of reactive gas admixture on transition metal cluster nucleation in a gas aggregation cluster source. J. Appl. Phys. 2012;112:114321. doi: 10.1063/1.4768528. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Polášek J, Mašek K, Marek A, Vyskočil J. Effects of oxygen addition in reactive cluster beam deposition of tungsten by magnetron sputtering with gas aggregation. Thin Solid Films. 2015;591:194–199. doi: 10.1016/j.tsf.2015.03.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shelemin A, et al. Preparation of metal oxide nanoparticles by gas aggregation cluster source. Vacuum. 2015;120:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.vacuum.2015.07.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rudd R, et al. Manipulation of cluster formation through gas-wall boundary conditions in large area cluster sources. Surf. Coatings Technol. 2017;314:125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2016.10.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Binns, C. et al. Preparation of hydrosol suspensions of elemental and core-shell nanoparticles by co-deposition with water vapour from the gas-phase in ultra-high vacuum conditions. J. Nanoparticle Res. 14 (2012).

- 53.Kylián O, et al. Control of wettability of plasma polymers by application of Ti nano-clusters. Plasma Process. Polym. 2012;9:180–187. doi: 10.1002/ppap.201100113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Atomic Spectra Database | NIST. at https://www.nist.gov/pml/atomic-spectra-database.

- 55.Horcas I, et al. WSXM: A software for scanning probe microscopy and a tool for nanotechnology. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2007;78:13705. doi: 10.1063/1.2432410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.