Abstract

The experiment was conducted to evaluate hormonal involvement in the adipose metabolism and lactation between high and low producing dairy cows in a hot environment. Forty Holstein healthy cows with a similar parity were used and assigned into high producing group (average production 41.44 ± 2.25 kg/d) and low producing group (average production 29.92 ± 1.02 kg/d) with 20 cows in each group. Blood samples were collected from caudal vein to determine the difference of hormones related to adipose metabolism and lactation. The highest, lowest, and average temperature humidity index (THI), recorded as 84.02, 79.35 and 81.89, respectively, indicated that cows were at the state of high heat stress. No significant differences between high and low producing groups were observed in the levels of nonestesterified fatty acid (NEFA), β-hydroxybutyrate (β-OHB), total cholesterol (TCHO), and insulin (INS) (P > 0.05). However, the very low density lipoprotein (VLDL), apolipoprotein B100 (apoB-100), high-density lipoprotein (HDL-C) and estrogen (E2) concentrations in high producing group were significantly higher than those of low producing group (P < 0.05). No significant differences between high and low producing groups were observed in the levels of prolactin (PRL) and progesterone (PROG) (P > 0.05), whereas high producing group had a rise in the insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) level compared with low producing group (P < 0.05). These results indicated that, during summer, high and low producing dairy cows have similar levels of lipid catabolism, but high producing dairy cows have advantages in outputting hepatic triglyceride (TG).

Keywords: Heat stress, High producing cows, Low producing cows, Lipid metabolism, Lactation hormones

1. Introduction

The appropriate ambient temperature for lactating cows ranges from 5 to 25°C, above which cows’ core body temperature begins to rise, leading to heat stress response (Ray et al., 1992). Over the past several decades, major advances in environmental cooling systems (Ortiz et al., 2015) and nutritional regulation have helped to ameliorate production losses, metabolic disorders and health problems during summer months. However, heat stress continues to be a challenge for global dairy industry (St-Pierre et al., 2003). In response to heat stress, dairy cows take metabolic adaptation measures to reduce heat load, such as elevating respiration rate (RR) and concomitantly reducing feed intake (Havlin and Robinson, 2015, Baumgard et al., 2011). Due to decreased feed intake, decreased energy intake cannot meet milk energy output with the consequence of negative energy balance, which has traditionally been assumed to be primarily responsible for decreases in milk production. Adipose tissues have been well known as an important regulator in energy balance and body weight, and it is mobilized aiming to compensate for the deficient induced by decreased feed intake in response to heat stress (Lanthier and Leclercq, 2014). Considering the rise in energy requirement of high producing dairy cows in lactation is parallel with increase in milk production, thereby aggravating negative energy balance, we hypothesized that lipolysis in high producing cows is more intense compared with low producing cows to maintain greater performance. In addition, secretions of prolactin (PRL), estrogen (E2) and progesterone (PROG) involved in the formation of mammary gland are inhibited in summer, which would have a negative effect on the formation of acinus and ductal system, and contribute to lower milk production.

Accordingly, the aim of the present study was to obtain insights into adipose metabolism characteristics and the levels of hormones associated to lactation in high and low producing cows in a hot environment by determining the concentration of factors related to lipid metabolism and lactation in plasma and providing theoretical reference for improving the performance of low producing cows in summer.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Experimental design and animals

The experiment was conducted at a farm located at Jiangsu province from 20 July to 20 August. Forty multiparous Holstein cows with similar ages, parities and lactation days were used and randomly assigned into high producing group (average production 41.44 ± 2.25 kg/d) and low producing group (average production 29.92 ± 1.02 kg/d) with 20 cows in each (Table 1).

Table 1.

Experimental cows were selected by milk production, parity, day in milk (DIM).

| Item | Milk production, kg/d | Parity | DIM, d |

|---|---|---|---|

| High producing dairy cows | 41.44 ± 2.25 | 2 | 168 ± 32 |

| Low producing dairy cows | 29.92 ± 1.02 | 2 | 174 ± 46 |

2.2. Diet ingredients and herd management

The cows were housed in a tie stall barn. Fans and sprinklers were used to cool the barn. The cows were fed total mixed ration 3 times daily. The ingredient and chemical composition of basal diet are shown in Table 2. The cows were milked 3 times daily (0730, 1130 and 1730 h) and the milk productions were recorded after each milking.

Table 2.

Ingredient and nutrient composition of basal diets (DM basis).

| Item | Amount |

|---|---|

| Ingredient, % | |

| Energy feed | |

| Corn | 17.20 |

| Brewer's dried grain | 8.99 |

| Corn silage | 23.38 |

| Dry alfalfa | 13.02 |

| Oat hay | 1.80 |

| Leymus chinensis | 1.69 |

| Protein feed | |

| Beet pulp | 5.40 |

| Cottonseed | 3.75 |

| Soybean meal | 8.53 |

| DDGS | 12.30 |

| Mineral feed | |

| NaHCO3 | 0.67 |

| NaCl | l0.45 |

| Limestone | 0.78 |

| CaHPO4 | 1.25 |

| Premix1 | 0.74 |

| Total | 100.00 |

| Nutrient composition, %2 | |

| CP | 15.30 |

| NEL, MJ/kg | 6.65 |

| EE | 3.36 |

| Neutral detergent fiber | 46.23 |

| Acid detergent fiber | 26.74 |

| Ash | 3.74 |

| Ca | 0.98 |

| Phosphorus | 0.47 |

DDGS = distillers dried grains with soluble; CP = crude protein; NEL = net energy for lactating; EE = ether extract.

Premix provided per kilogram of diet: VA 1,350,000 IU; VD3 275,000 IU; VE 330,000 IU; nicotinic acid 2,700 mg; Cu 1,600 mg; Fe 4,700 mg; Mn 4,200 mg; Zn 8,500 mg; Se 80 mg; Co 60 mg.

The value of NEL was calculated, other values were measured.

2.3. Blood sampling

Blood samples were collected via caudal vein before feeding on the last day of the experiment. Samples were cooled on wet ice, centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 min at room temperature. The plasmas were aliquoted into 1.5-mL eppendorf tubes and stored at −20°C till further analysis.

2.4. Parameters and methods

2.4.1. Temperature and humidity index measurements

Five relative humidity and temperature sensors (Tianjin meteorological instrument corporation, DHM-2A type, temperature ranges from −36 to +46°C, relative humidity ranges from 10 to 100%) were placed in different locations, 1.5 m above the floor and out of direct sunlight. Data were recorded at 0800, 1400 and 2000 h. Temperature humidity index (THI) was calculated as: THI = 0.72 (Td + Tw) + 40.6, where Td is dry bulb air temperature, and Tw is wet bulb air temperature (Thom, 1959).

2.4.2. Rectal temperature and respiratory rate measurements

Rectal temperature (RT) and respiratory rate (RR) were determined at 0800, 1400 and 2000 h daily. Respiratory temperatures were detected using animal thermometer. Respiratory rates were determined by observing flank movements of the cows. Numbers of breaths in a 3-consecutive-minute period were recorded and then converted to breaths/min.

2.4.3. Blood biochemical parametres

Nonestesterified fatty acid (NEFA) level in serum was detected by chemical colorimetric. High-density lipoprotein (HDL-C) concentration was measured with selective precipitation method. Enzyme treatment was used to determine total cholesterol (TCHO) level. Antibody-sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to detect the very low density lipoprotein (VLDL), apolipoprotein B100 (apoB-100), β-hydroxybutyrate (β-OHB), insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), E2, PROG, PRL and glucocorticoid concentrations. Insulin (INS) was detected by radioimmunoassay. Above kits were purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Institute of Biology except INS kit from Beijing North Institute of Biotechnology.

2.5. Statistical analysis

All the statistical analysis was conducted using a SPSS statistical software program (version. 17.0 for windows, SPSS; IBM SPSS Company, Chicago, IL, USA). Data were subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the differences between mean values between the different groups were identified by the least significant difference (LSD). Differences with a P-value lower than 0.05 were considered as significant. Data presented are means ± SEM.

3. Results

3.1. Temperature and humidity index

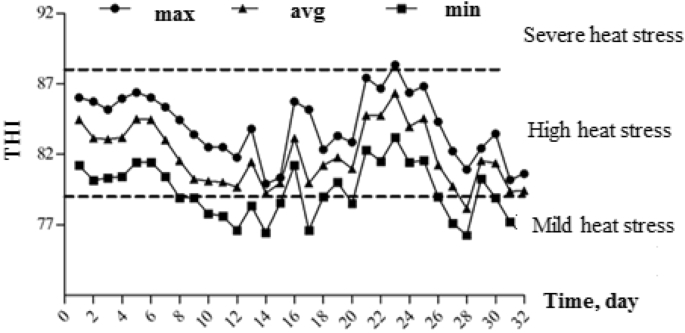

During the experiment period, THI observed were between 76.15 and 88.34. Average daily THI were 81.89 with the lowest of 79.35 and highest of 84.02 (Fig. 1). According to the livestock weather safety index (Armstrong, 1994): THI < 72 indicates no heat stress, 72 ≤ THI ≤ 79 indicates mild heat stress, 79 < THI ≤ 88 is considered high heat stress, and THI > 88 indicates severe heat stress. The experiment lasted 33 days, one of which was in mild heat stress status, and the rest days were in high heat stress.

Fig. 1.

The temperature humidity index (THI) of barn during experimental period (max, min and avg represent the highest, lowest, and average THI, respectively).

3.2. Rectal temperature and respiratory rate

As is shown in Table 3, high producing cows exhibited higher RT at 1400 h than at 0800 h (P < 0.05), indicating that high producing cows upregulated RT at the hottest time of day to increase the temperature difference between RT and ambient temperature thereby improving heat loss efficiency. The RT started to decrease at 2000 h and reached 38.96°C at 0800 h in the next morning. Whereas the RT of low producing cows were above 39°C all day, which is an indicator of heat stress (West, 2003). The RR of high producing cows was higher at 1400 h than at 0800 h (P < 0.05), suggesting heat loss via panting at noon, it decreased to 83.83 breathes/min at 2000 h, whereas low producing cows consistently maintained higher RR.

Table 3.

Physiological indices of dairy cows.

| Dairy cows |

||

|---|---|---|

| Item | High producing | Low producing |

| RT, °C | ||

| 0800 | 38.96 ± 0.08b | 39.21 ± 0.11 |

| 1400 | 39.43 ± 0.11a | 39.37 ± 0.11 |

| 2000 | 39.27 ± 0.11a | 39.24 ± 0.13 |

| RR, breathes/min | ||

| 0800 | 82.02 ± 3.23d | 83.39 ± 3.09b |

| 1400 | 86.50 ± 3.05c | 86.34 ± 3.23a |

| 2000 | 83.83 ± 3.26d | 87.32 ± 3.09a |

RT = rectal temperature; RR = respiratory rate.

a–d Within a column, means without a common superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05).

3.3. Blood profile related to lipolysis and adipose transportation

As is shown in Table 4, compared with low producing cows, high producing cows had higher HDL-C, VLDL and apoB-100 concentrations (P < 0.05), but no significant difference was observed in NEFA、TCHO and β-OHB concentrations between the 2 groups (P > 0.05).

Table 4.

Lipid catabolism and transportation in high and low-producing Holstein cows during heat stress.

| Item | High producing dairy cows | Low producing dairy cows |

|---|---|---|

| NEFA, μmol/L | 509.61 ± 32.78 | 549.96 ± 29.93 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 3.57 ± 0.28a | 2.84 ± 0.13b |

| TCHO, mmol/L | 5.64 ± 0.42 | 4.90 ± 0.29 |

| VLDL, mmol/L | 0.76 ± 0.04a | 0.64 ± 0.03b |

| β-OHB, μg/mL | 58.52 ± 6.81 | 69.34 ± 6.14 |

| ApoB-100, μg/mL | 128.56 ± 8.40a | 105.58 ± 10.25b |

NEFA = non-esterified fatty acid; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein; TCHO = total cholesterol; VLDL = very low density lipoprotein; β-OHB = β-hydroxybutyrate; ApoB-100 = apolipoprotein B100.

a,b Within a row, means without a common superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05).

3.4. Adipose metabolism and lactation hormones

Table 5 shows that, during heat stress high producing cows had greater GC, estrogen and IGF-1 levels than low producing cows (P < 0.05), whereas INS, PRL and PROG levels showed no differences between the groups (P > 0.05).

Table 5.

Levels of hormone related to lipid metabolism and lactation in high and low producing Holstein cows during the heat stress.

| Item | High producing dairy cows | Low producing dairy cows |

|---|---|---|

| INS, μIU/mL | 14.98 ± 0.83 | 15.93 ± 0.79 |

| GC, pg/mL | 269.99 ± 16.72a | 220.303 ± 10.28b |

| Estrogen, g/mL | 73.09 ± 7.13a | 56.89 ± 2.52b |

| PRL, ng/mL | 105.83 ± 10.02 | 98.32 ± 12.30 |

| PROG, ng/mL | 0.75 ± 0.099 | 0.58 ± 0.087 |

| IGF-1, ng/mL | 548.08 ± 97.29a | 317.77 ± 32.17b |

INS = insulin; GC = glucocorticoid; PRL = prolactin; PROG = progesterone; IGF-1 = insulin-like growth factor-1.

a,b Within a row, means without a common superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05).

4. Discussion

4.1. Adipose metabolism in high and low producing dairy cows

4.1.1. Lipolysis

In response to heat stress, adipose tissue lipid is mobilized to provide energy used to counter the hyperthermia, leading to a decrease in body reserves and an increase in delivery of NEFA to blood circulation from lipolysis of adipose tissue. Glucocorticoid, a kind of steroid hormones secreted by epinephros, plays an important role in promoting the lipolysis. The results in the current study indicated that high producing cows tended to have increased GC levels compared with low producing cows. However, no treatment difference in NEFA concentrations was shown between high and low milk producing groups, which illustrated that the lipolysis levels of high and low producing dairy cows were basically equivalent during heat stress. This could be explained by considering that dairy cows try their best to maintain body heat balance through reducing both of feed intake and heat production during heat stress, whereas the β-oxidation of NEFA may produce more metabolic heat than that of other energy material, such as carbohydrates. Thus, lipolysis is not an ideal energy source for dairy cows during heat stress thereby homothetic adaptations act to suppress lipid mobilization. The average INS level for dairy cow in thermoneutral condition is 12.98 μIU/mL (Wheelock et al., 2010). In our study, INS levels in high and low producing cows increased by 14.35 and 21.60% of 12.98 μIU/mL, respectively, which could be explained for the increased INS sensitivity response of pancreas to glucose during hyperthermia. Early reports have shown INS concentrations in cattle increased from 9.03 to 13.00 μIU/mL in high temperature (O'Brien et al., 2010), which is in agreement with our results, and plasma INS level of rat housed in climate chamber (air temperature, 50°C; relative humidity, 50%) increased by 224% (Torlinska et al., 1987). INS is a potent antilipolytic hormone. An increase in plasma INS concentration can inhibit adipose triglyceride (TG) mobilization in summer.

4.1.2. Adipose transportation

Nonestesterified fatty acids from lipolysis were transported to the liver where they were oxidized or re-esterified into TG stored in the liver. The very low density lipoprotein is the primary way to deliver hepatic excess TG to blood circulation in ruminant. Apolipoprotein B100 as a structural protein and the main apolipoprotein of VLDL is essential for the assembly and secretion of VLDL by connecting lipoprotein and specific receptors in a form of ligand. The very low density lipoprotein assembly and secretion rate is affected by the activity and gene expression of apoB-100. It was proved that in response to apoB100 synthesis disorders, hepatic synthesis of lipoproteins was less efficient, leading to hepatic TG accumulation (Mazur et al., 1992). In the current study, cows with high production showed higher apoB-100 and VLDL levels compared with cows with low production, suggesting that high producing cows have an advantage to output hepatic TG to blood for synthesis of milk fat or to be used by other tissues and subsequently alleviate the negative energy balance and maintain high milk production. Estrogen affects synthesis and secretion of VLDL in liver by controlling expression of apolipoprotein mRNA in liver. Previous study indicated that hepatic VLDL-TG production was significantly decreased in ovariectomized rats (Barsalani et al., 2010). In our present study, estrogen levels in high producing cows were higher than those of low producing cows, which is consistent with their higher VLDL concentrations, indicating that high producing cows have an advantage in the acquisition of lipid nutrition.

4.2. Lactation related factors in high and low producing dairy cows

Mammary gland is a complex organ that undergoes development and differentiation under the control of a number of neuroendocrine hormones and growth factors secreted by mammary gland and other tissues (Murney et al., 2015). These various hormones corporately regulate the growth and development of mammary gland in endocrine, paracrine and autocrine manners. Prolactin is a peptide hormone of the anterior pituitary gland. It plays a major role in all aspects of mammary development, onset of lactation and maintenance of lactation. An increase in the expression of prolactin receptor (PRLR) in mammary epithelial cells was detected during pregnancy and lactation (Kelly et al., 2002) and daily injections of prolactin-release inhibitor quinagolide to dairy cows significantly decreased milk production during peak lactation (Lacasse et al., 2011). Whereas another study showed that lactation performance of dairy cows was not affected by exogenous prolactin administration treatment in both early and peak lactation (Plaut et al., 1987). One possible mechanism for this difference is that the binding sites on the mammary gland are saturated thus limiting the ability of the mammary gland to respond to additional PRL. In our study, there was no significant difference in the levels of PRL between low and high producing cows, indicating PROG was not a major regulatory hormone of milk production during lactation, which was consistent with Plaut. The role of PROG in the development of mammary gland is to promote ductal branching and acinus formation. The current study showed there was no significant difference in the levels of PROG between low and high producing cows, the reason for that could be there was no PROG receptor in lactating mammary cells or receptors might lose function. Thus, once started lactation, milk production was out of control of PROG.

Milk secretion capacity of mammary gland is directly affected by the number of alveolar in lactation period. Hyperthermia inhibits mammary epithelial cells proliferation in summer. It has been reported that high temperature treatment inhibited proliferation and induced apoptosis in mammary epithelial cells (Collier et al., 2006, Ahmed et al., 2015). Insulin-like growth factor-1 has an ability to prompt mammary growth and differentiation, maintain cell function and prevent apoptosis (Akers, 2006). In the present study, IGF-1 concentration was higher in high producing cows than that in low producing cows, indicating that high producing cows has an advantage in maintaining mammary cells vitality and lactation performance.

5. Conclusion

High and low producing dairy cows have similar levels of lipolysis, but high producing dairy cows have advantages in outputting hepatic TG during heat stress.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the earmarked fund for National Science and Technology Project: Production Technique Integration and Industrialization Demonstration of Dairy Health Farming in Southern Pastoral Area. (2012BAD12B10).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

References

- Ahmed B., Diana A., Averill B. Thermotolerance induced at a mild temperature of 40°C alleviates heat shock-induced ER stress and apoptosis in HeLa cells. BBA-MOL Cell Res. 2015;1853(1):52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akers R.M. Major advances associated with hormone and growth factor regulation of mammary growth and lactation cows. J Dairy Sci. 2006;89:1222–1234. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(06)72191-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong D.V. Symposium-nutrition and heat stress interaction with shade and cooling. J Dairy Sci. 1994;77(7):2044–2050. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(94)77149-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsalani R., Chapados N.A., LavoieHepatic J.M. VLDL-TG production and MTP gene expression are decreased in ovariectomized rats: effects of exercise training. Hormone Metabolic Res. 2010;42(12):860–867. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1267173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgard L.H., Wheelock J.B., Sanders S.R., Moore C.E., Green H.B., Waldron M.R. Post absorptive carbohydrate adaptations to heat stress and monensin supplementation in lactating Holstein cows. J Dairy Sci. 2011;94(11):5620–5633. doi: 10.3168/jds.2011-4462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier R.J., Stiening C.M., Pollard B.C. Use of gene expression micro arrays for evaluating environmental stress tolerance at the cellular level in cattle. J Anim Sci. 2006;8(1):1–13. doi: 10.2527/2006.8413_supple1x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havlin J.M., Robinson P.H. Intake, milk production and heat stress of dairy cows fed a citrus extract during summer heat. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2015;208:23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly P.A., Bachelota A., Kedziaa C., Hennighausenb L., Ormandyc C.J., Kopchickd J.J. The role of prolactin and growth hormone in mammary gland development. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;197(1–2):127–131. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00286-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacasse P., Lollivier V., Bruckmaier R.M., Boisclair Y.R., Wagner G.F., Boutinaud M. Effect of the prolactin-release inhibitor quinagolide on lactating dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 2011;94(3):302–1309. doi: 10.3168/jds.2010-3649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanthier N., Leclercq I.A. Adipose tissues as endocrine target organs. Gastroenterology. 2014;28(4):545–558. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur A., Ayrault-Jarrier M., Chilliard Y., Rayssiguier Y. Lipoprotein metabolism in fatty liver dairy cows. Diabetes Metab. 1992;18:145–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murney R., Stelwagen K., Wheeler T.T., Margerison J.K., Singh K. The effects of milking frequency in early lactation on milk yield, mammary cell turnover, and secretory activity in grazing dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 2015;98(1):305–311. doi: 10.3168/jds.2014-8745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’brien M.D., Rhoads R.P., Sanders S.R., Duff G.C., Baumgard L.H. Metabolic adaptations to heat stress in growing cattle. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2010;38(2):86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz X.A., Smith J.F., Rojano F., Choi C.Y., Bruer J., Steele T. Evaluation of conductive cooling of lactating dairy cows under controlled environmental conditions. J Dairy Sci. 2015;98(3):1759–1771. doi: 10.3168/jds.2014-8583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaut K., Bauman D.E., Agergaard N., Akers R.M. Effect of exogenous prolactin administration on lactational performance of dairy cows. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 1987;4(4):4279–4290. doi: 10.1016/0739-7240(87)90024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray D.E., Halbach T.J., Armstrong D.V. Season and lactation number effects on milk production and reproduction of dairy cattle in Arizona. J Dairy Sci. 1992;75(11):2976–2983. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(92)78061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-Pierre N.R., Cobanov B., Schnitkey G. Economic losses from heat stress by US livestock industries. J Dairy Sci. 2003;86(E Suppl.):E52–E77. [Google Scholar]

- Thom E.C. The discomfort index. Weather Wise. 1959;12:5640. [Google Scholar]

- Torlinska T., Banach R., Paluszak J. Hyperthermia effect on lipolytic processes in rat blood and adipose tissue. Acta Physiol Pol. 1987;38(4):361–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West J.W. Effects of heat-stress on production in dairy cattle. J Dairy Sci. 2003;86(6):2131–2144. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(03)73803-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheelock J.B., Rhoads R.P., VanBaale M.J., Sanders S.R., Baumgard L.H. Effects of heat stress on energetic metabolism in lactating Holstein cows. J Dairy Sci. 2010;93(2):644–655. doi: 10.3168/jds.2009-2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]