Abstract

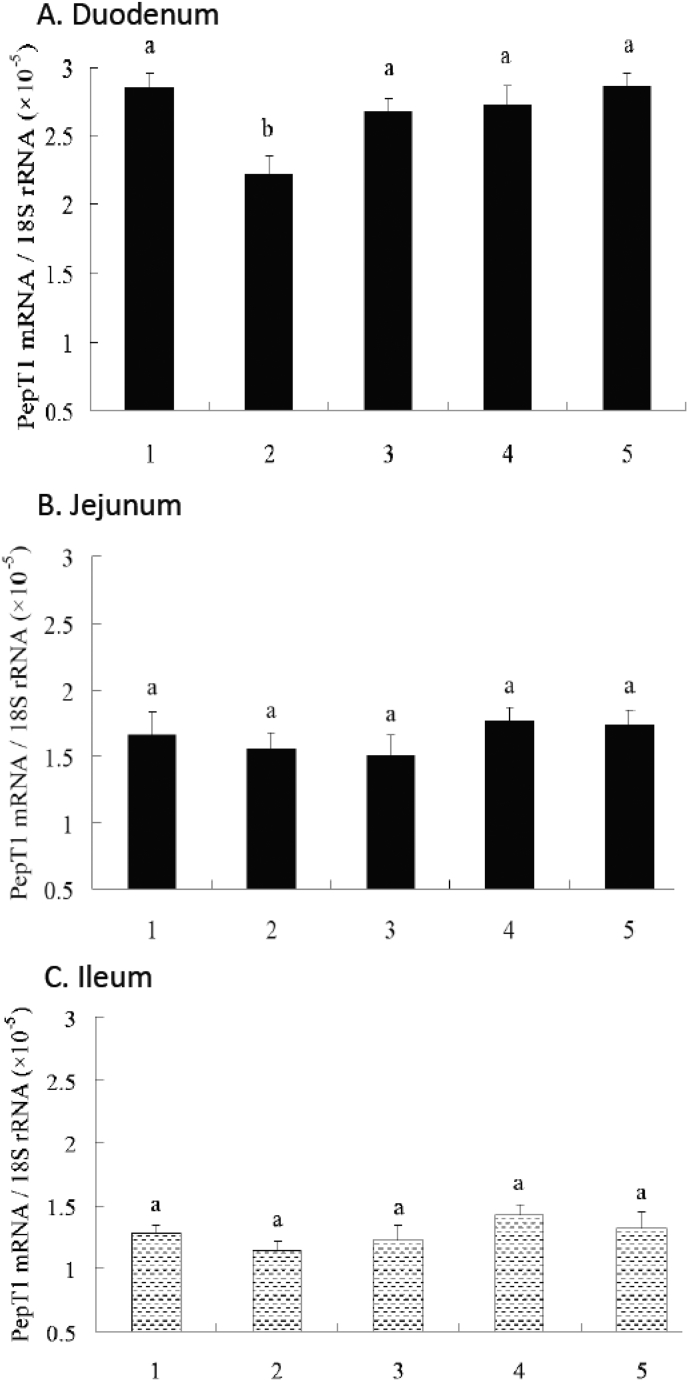

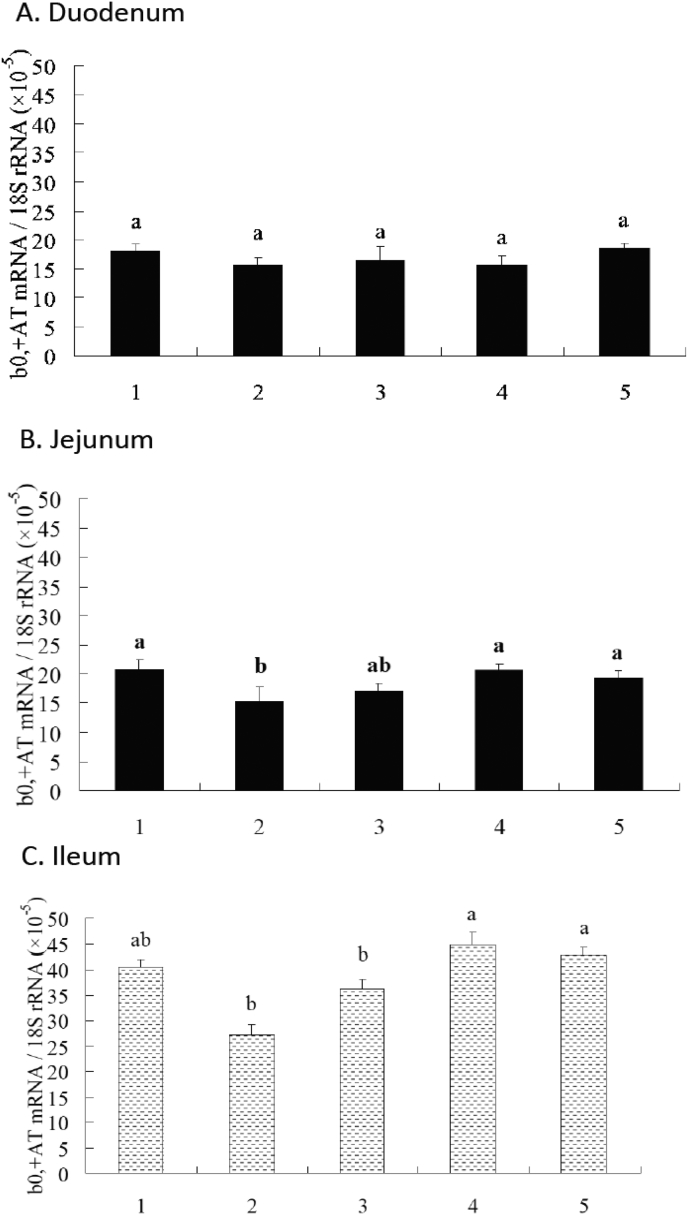

This study was conducted to investigate the effect of dietary protease supplementation on the growth performance, nutrient digestibility, intestinal morphology, digestive enzymes and gene expression in weaned piglets. A total of 300 weaned piglets (21 days of age Duroc × Large White × Landrace; initial BW = 6.27 ± 0.45 kg) were randomly divided into 5 groups. The 5 diets were: 1) positive control diet (PC), 2) negative control diet (NC), and 3) protease supplementations, which were 100, 200, and 300 mg per kg NC diet. Results indicated that final BW, ADG, ADFI, crude protein digestibility, enzyme activities of stomach pepsin, pancreatic amylase and trypsin, plasma total protein, and intestinal villus height were higher for the PC diet and the supplementations of 200 and 300 mg protease per kg NC diet than for the NC diet (P < 0.05). Supplementations of 200 and 300 mg protease per kg NC diet significantly increased the ratio of villus height to crypt depth (VH:CD) of duodenum, jejunum and ileum compared with NC diet (P < 0.05). Feed to gain ratio, diarrhea index, blood urea nitrogen, and diamine oxidase were lower for the PC diet and supplementations of 200 and 300 mg protease per kg NC diet than for the NC diet (P < 0.05). Piglets fed the PC diet had a higher peptide transporter 1 (PepT1) mRNA abundance in duodenum than piglets fed the NC diet (P < 0.05), and supplementations of 100, 200 and 300 mg protease per kg NC diet increased the PepT1 mRNA abundance in duodenum (P < 0.05) comparing with the NC diet. Piglets fed the PC diet had a higher b0,+AT mRNA abundance in jejunum than piglets fed the NC diet (P < 0.05), and supplementations of 200 and 300 mg protease per kg NC diet increased the b0,+AT mRNA abundance in jejunum and ileum comparing with the NC diet (P < 0.05). In summary, dietary protease supplementation increases growth performance in weaned piglets, which may contribute to the improvement of intestinal development, protein digestibility, nutrient transport efficiency, and health status of piglets when fed low digestible protein sources.

Keywords: Growth performance, Nutrient digestibility, Morphology, Gene expression, Weaned piglets

1. Introduction

The cost of pork production mainly comes from the feed, and the significant increases of feed cost during the last decade have reduced profit margins of pork production (Schmit et al., 2009). The use of exogenous feed enzymes has been one of the most widely used strategies to improve nutrient utilization efficacy and reduce the feed cost in the animal industry (Adeola and Cowieson, 2011). Proteases have been routinely included to swine diets for many years as part of enzyme cocktails containing xylanases, celluase, amlyase and glucanases (Yin et al., 2001, Yin et al., 2004, Omogbenigun et al., 2004, Ji et al., 2008, Jo et al., 2012). An enzyme cocktail (β-glucanase, xylanase and protease) improved the digestibilities of crude protein and energy at ileal and the total tract levels of the hulless barley based diets for young piglets (Yin et al., 2001). Similarly, an enzyme cocktail (arabinoxylanase and protease) improved the nutritional value of diets containing wheat bran or rice bran for growing pig (Yin et al., 2004). Dietary supplementation with enzyme cocktails including proteases improved nutrient utilization and growth performance in weaned pigs (Omogbenigun et al., 2004). A beta-glucanase-protease enzyme blend product improved the ileal digestibility of crude protein and other nutrients (Ji et al., 2008). Supplementation of 0.05% of enzyme cocktails (α-amylase, β-mannanase, and protease) to a corn and soybean meal (SBM) diet or a complex diet improved the performance of growing pigs (Jo et al., 2012). Although the above positive effects have been reported, the contribution of protease on these improvements is still not clear. Recently, proteases have been used alone in the pig diets with the availability of several commercial stand-alone proteases, and new mechanisms of action have been proposed (O'Doherty and Forde, 1999, McAlpine et al., 2012a, McAlpine et al., 2012b, Guggenbuhl et al., 2012). However, efficacy of protease in weaned piglets and its mechanisms behind are still not clear especially when low digestible protein sources are used. Therefore, this study was conducted to investigate the effect of dietary supplementation with protease on the growth performance, nutrient digestibility, intestinal morphology, digestive enzymes and gene expression in weaned piglets.

2. Materials, methods and management

2.1. Animals and diets

A total of 300 weaned piglets (21 days of age Duroc × Large White × Landrace; initial BW = 6.27 ± 0.45 kg) were provided by Wens Group (Guangzhou, Guangdong). They were randomly divided into 5 groups (60 piglets per group and 10 piglets per pen). All piglets were housed in environmentally controlled rooms equipped with water nipples and stainless-steel feeders. Diets and water were offered ad libitum throughout the duration of the experiment. Room temperature and air humidity were maintained at 25°C and 50%, respectively. All procedures were approved by the Animal Care Committee at the South China Agricultural University. The animals used in this experiment were cared for in accordance with the guidelines established by University Council of Animal Care.

As shown in Table 1, the basal diets used were formulated to meet the nutrient requirement of pigs (NRC, 2012). For 14 d, piglets were fed the following diets: 1) a standard commercial diet, named as a positive control (PC) diet (22.21% soybean meal, 5% whey protein and 3% fish meal), 2) a negative control (NC) diet (30.06% soybean protein without whey protein and fish meal), 3) 100 mg protease per kg NC diet, 4) 200 mg protease per kg NC diet, and 5) 300 mg protease per kg NC diet. The protease used is a commercial protease (Jefo, Saint-Hyacinthe, Canada). The five diets were iso-nitrogenous and iso-caloric, and pelleted at a condition of 0.4 MPa and 75°C. The major source of protein in the PC diet was from fishmeal and concentrated whey protein, which were substituted with soybean meal in the NC diet.

Table 1.

Ingredients and nutrient composition of the basal diet (as fed basis).

| Item | PC | NC |

|---|---|---|

| Ingredient, g/kg | ||

| Corn, 8% CP | 45.10 | 45.10 |

| Soybean | 142.10 | 160.60 |

| Whey power, 12% CP | 120.00 | 120.00 |

| Soybean meal, 43% CP | 50.00 | 100.00 |

| Wheat flour | 50.00 | 50.00 |

| Concentrated whey protein, 34% CP | 50.00 | 0.00 |

| Concentrated soybean protein, 64% CP | 30.00 | 40.00 |

| Spray-dry plasma | 30.00 | 30.00 |

| Fishmeal | 30.00 | 0.00 |

| Glucose | 25.00 | 25.00 |

| Sucrose | 20.00 | 20.00 |

| Calcium hydrogen phosphate | 7.00 | 11.50 |

| Soy oil | 7.60 | 5.20 |

| L-Lysine | 3.10 | 4.00 |

| Limestone | 3.60 | 4.00 |

| ZnO | 2.50 | 2.50 |

| L-Threonine | 1.20 | 1.80 |

| DL-Methionine | 1.30 | 1.70 |

| Choline | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| L-Tryptophan | 0.50 | 0.60 |

| Premix1 | 10.00 | 10.00 |

| Nutrient composition, %2 | ||

| DE, MJ/kg | 14.52 | 14.52 |

| CP | 21.00 | 21.00 |

| Ca | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| P | 0.45 | 0.45 |

| NaCl | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| Lysine | 1.53 | 1.54 |

| Met + Cys | 0.86 | 0.87 |

| Threonine | 1.06 | 1.05 |

| Tryptophan | 0.31 | 0.32 |

| Arginine | 0.65 | 0.64 |

| Valine | 1.08 | 1.09 |

| Leucine | 1.53 | 1.55 |

| Isoleucine | 0.86 | 0.87 |

| Histidine | 0.50 | 0.48 |

| Phenylalanine | 0.94 | 0.94 |

PC = positive control diet; NC = negative control diet.

Premix provided per kg of diet: vitamin A,19,200 IU; vitamin D3, 4,800 IU; vitamin E, 60 IU; vitamin K3, 6 mg; vitamin B1, 6 mg; vitamin B2, 12 mg; vitamin B6, 7.2 mg; vitamin B12, 0.05 mg; niacin, 60 mg; calcium pantothenate, 30 mg; nicotinic acid, 15 mg; folic acid, 3.60 mg; biotin, 0.60 mg; Fe, 305 mg; Cu, 250 mg; Zn, 1,910 mg; Mn, 51 mg; I, 0.50 mg; Se, 0.50 mg; Co, 0.50 mg.

Nutrient levels were calculated.

2.2. Data recording and sample collection

Health status was monitored daily, and BW and feed intake was registered throughout the study. Average daily gain (ADG), average daily feed intake (ADFI), feed to gain ratio, and diarrhea index were calculated.

Blood samples were collected at 0800 via the jugular vein into 10 mL heparinized vacuum and then centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 min to collect plasma. Plasma was frozen at −80°C until analysis. All blood samples were analyzed in duplicate.

Pigs were euthanized with an overdose injection of 10% sodium pentobarbital before sampling. The entire intestine was then removed and dissected free of mesenteric attachments and placed on a smooth and cold surface. The duodenum, jejunum and ileum were separated. The isolated intestinal segments were immediately opened lengthwise following the mesentery line and flushed with ice-cold saline (154 mmol/L NaCl, 0.1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], pH 7.4) and divided into 15-cm segments. Each tube, which contained approximately 15 g of tissue, was tightly capped and stored at −80°C. For morphology measurement, samples were flushed and fixed in 10% buffered formalin at least 48 h before histology process.

At day 14, feces samples were collected and added with 10% HCl, and then stored at–80°C before analysis. Before analysis, samples were dried at 65°C and grounded into fine powder and then apparent total tract digestibility was measured.

2.3. Chemical analysis

All samples of diets and feces were analyzed in triplicate for dry matter using AOAC (2006; 930.15), crude protein using AOAC (2006; #990.03), and energy using bomb calorimeter (Calvin C 6040, IKA, China).

2.4. Morphology measurement

Samples were cut and inserted into cassettes (1 pig/cassette) and assigned a random number. Cassettes were embedded in parafilm and slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Villi and crypts were measured (μm) by 3 trained personals that were unaware of treatments (6 pens/group and 1 pig/pen).

2.5. Digestive enzyme activity

The stomach digesta and pancreatic samples were collected and stored immediately at −80°C. For the analysis, the digesta and pancreatic samples were thawed at room temperature and homogenized in 5 volumes of ice-cold 0.9% sodium chloride solution. The homogenate was centrifuged at 13,800 × g for 20 min at 4°C and the supernatant was analyzed for enzyme activities (Fan et al., 2009). Amylase and protease activities were determined. Lipase (EC. 3.l.l.3) activity was assayed using the method described by Tietz and Fiereck (1966). All determinations were performed in duplicate.

2.6. Biochemical parameters

The concentration of glucose, total protein (TP), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and albumin in plasma samples were determined by spectrophotometric method using commercial kits (Nanjiang Jiancheng Bio, Nanjing, China). Total globulin was determined by subtracting albumin from total protein. Diamine oxidase (DAO) activity in plasma was determined using spectrophotometry as described by a previous method (Hosoda et al., 1989).

2.7. RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was isolated from 100 mg of jejunum using TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen) and treated with DNase I (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The RNA quality was checked by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, stained with 10 μg/mL ethidium bromide. The RNA had an OD260 to OD280 ratio between 1.8 and 2.0. Synthesis of the first strand cDNA was performed with oligo(dT) 20 and Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen).

2.8. Quantification mRNA by Real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis

Real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Green PCR Mix (Takara, Dalian, China), containing MgCl2, dNTP, and Hotstar Taq polymerase (Takara, Dalian, China). Two microliters cDNA template was added to a total volume of 25 μL containing 12.5 μL SYBR Green mix, and 1 μM each of forward and reverse primers. Primers for HATs and 18S were design with Primer 3 (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3/primer3_code.html) based on porcine sequence to produce an amplification product that spanned at least two exons (Table 2). We used the following protocol: 1) denaturation program (15 min at 95°C); 2) amplification and quantification program, repeated 45 cycles (15 s at 95°C, 15 s at 58°C, 15 s at 72°C); 3) melting curve program (60 to 99°C with heating rate of 0.1°C/s and fluorescence measurement). We used an abundantly expressed gene, 18S, as the internal control to normalize the amount of starting RNA used for RT-PCR for all samples. Amplification and melt curve analysis was performed in ABI 7500 (Applied BioSystems). Melt curve analysis was conducted to confirm the specificity of each product, and the size of products were verified on ethidium bromide-stained 2% agarose gels in Tris acetate–EDTA buffer. The identity of each product was confirmed by dideoxy-mediated chain termination sequencing at Takara Biotechnology, Inc. We calculated the relative expression ratio (R) of mRNA by 2−ΔCt (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Real-time PCR efficiencies were acquired by the amplification of dilution series of cDNA according to the equation 10 −1/slope and were consistent between target mRNA and 18S. Negative controls were performed in which water was substituted for cDNA.

Table 2.

Primers used in real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).

| Gene | Primer sequence |

|---|---|

| b0,+AT | Sense 5′-ATCGGTCTGGCGTTTTAT-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-GGATGTAGCACCCTGTCA-3′ | |

| PepT1 | Sense 5′-TTTAGGCATCGGAGTAAGAAGT-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-GTCAAACAAAAGCCCAGAACAT-3′ | |

| 18S | Sense 5′-AATTCCGATAACGAACGAGACT-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-GGACATCTAAGGGCATCACAG-3′ |

2.9. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 18.0 and presented as mean ± SE. The difference between means was assessed by ANOVA and Ducan's test was then used to compare data among treatments. Statistical significance between treatments was based on P < 0.05.

3. Results

As shown in Table 3, piglets fed the PC diet had higher final BW, ADG, and ADFI than piglets fed the NC diet (P < 0.05). Piglets fed the PC diet had lower feed to gain ratio and diarrhea index than piglets fed the NC diet (P < 0.05). Comparing with the NC diet, all protease supplementation diets increased the final BW, ADG and ADFI, and reduced feed to gain ratio and diarrhea index in piglets (P < 0.05). However, there were no significant differences in final BW, ADG, ADFI, feed to gain ratio, and diarrhea index among the protease supplementation diets and the PC diet (P > 0.05).

Table 3.

Effect of protease supplementation on the growth performance and diarrhea incidence of weaned piglets.

| Item | PC | NC | Protease supplementation, mg/kg NC as fed basis |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 200 | 300 | |||

| Initial BW, kg | 6.27 ± 0.00 | 6.27 ± 0.00 | 6.27 ± 0.00 | 6.27 ± 0.00 | 6.27 ± 0.00 |

| Final BW, kg | 10.21 ± 0.37b | 9.89 ± 0.48a | 10.12 ± 0.39b | 10.39 ± 0.47b | 10.37 ± 0.44b |

| ADG, g | 281.12 ± 26.46b | 258.19 ± 34.30a | 274.69 ± 27.56b | 293.95 ± 33.52c | 292.64 ± 29.70c |

| ADFI, g | 329.36 ± 26.83b | 312.32 ± 27.76a | 327.00 ± 26.14b | 343.44 ± 30.48c | 344.80 ± 33.33c |

| Feed to gain ratio | 1.17 ± 0.03b | 1.21 ± 0.04a | 1.19 ± 0.04b | 1.17 ± 0.03b | 1.18 ± 0.02b |

| Diarrhea incidence, % | 1.79 ± 0.8b | 3.37 ± 0.76a | 2.34 ± 0.95b | 1.84 ± 0.69b | 1.91 ± 0.83b |

PC = positive control diet; NC = negative control diet; BW = body weight; ADG = average daily gain; ADFI = average daily feed intake.

a,b,c Within a row, means without a common superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05), n = 6.

As shown in Table 4, the PC diet had higher crude protein digestibility than the NC diet (P < 0.05). Comparing with the NC diet, both 200 and 300 mg protease per kg NC diet significantly increased the crude protein digestibility (P < 0.05). Although 100 mg protease per kg NC diet tended to have higher crude protein digestibility, there was no significant difference between the NC and 100 mg protease per kg NC groups (P > 0.05). There were no significant differences in the digestibility of dry matter and gross energy among all groups (P > 0.05). There were no significant differences in the digestibility of crude protein between the PC group and the groups with inclusion of protease (P > 0.05).

Table 4.

Effects of dietary supplementation of protease on the apparent total tract digestibility (%) of weaned piglets.

| Item | PC | NC | Protease supplementation, mg/kg NC diet as fed basis |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 200 | 300 | |||

| Dry mater | 89.67 ± 2.15 | 87.40 ± 3.27 | 86.92 ± 1.78 | 89.29 ± 2.21 | 88.61 ± 2.35 |

| Gross energy | 88.50 ± 2.66 | 86.27 ± 2.45 | 86.73 ± 1.99 | 87.95 ± 3.09 | 88.07 ± 1.86 |

| Crude protein | 87.19 ± 1.94a | 80.23 ± 2.65b | 83.59 ± 2.17ab | 87.66 ± 2.86a | 86.85 ± 3.14a |

PC = positive control diet; NC = negative control diet.

a,b Within a row, means without a common superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05), n = 6.

As shown in Table 5, piglets in the PC group had higher enzyme activities of stomach pepsin, pancreatic amylase, and trypsin when compared with the piglets in the NC group (P < 0.05). Supplementations of protease (100, 200, and 300 mg protease per kg NC diet) significantly increased the enzyme activities of pancreatic amylase and trypsin when compared with the NC group (P < 0.05). Both of 200 and 300 mg protease per kg NC diet significantly increased the enzyme activities of stomach pepsin when compared with the NC group (P < 0.05). Although 100 mg protease per kg NC diet group tended to have higher enzyme activity of stomach pepsin, there was no significant difference between the NC diet and 100 mg protease per kg NC diet groups (P > 0.05). There were no significant differences in lipase activity among all groups (P > 0.05).

Table 5.

Effects of dietary supplementation of protease on digestive enzyme activities (IU/g digesta or tissue) of weaned piglets.

| Item | PC | NC | Protease supplementation, mg/kg NC as fed basis |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 200 | 300 | |||

| Pepsin | 275.1 ± 30.03ab | 206.1 ± 28.8c | 225.4 ± 21.3bc | 247.6 ± 18.7b | 266.7 ± 24.2a |

| Pancreatic amylase | 5.19 ± 0.43a | 4.25 ± 0.35c | 4.83 ± 0.47b | 5.02 ± 0.25a | 5.10 ± 0.33a |

| Trypsin | 4.85 ± 0.34ab | 3.78 ± 0.40c | 4.46 ± 0.42b | 4.78 ± 0.51ab | 5.13 ± 0.29a |

| Lipase | 22.39 ± 2.5 | 20.51 ± 2.28 | 23.05 ± 2.31 | 23.94 ± 1.92 | 22.54 ± 2.07 |

PC = positive control diet; NC = negative control diet.

a,b,c Within a row, means without a common superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05), n = 6.

As shown in Table 6, piglets in the PC group had higher villus height of duodenum, jejunum, and ileum when compared with the piglets in NC group (P < 0.05). Inclusions of 200 and 300 mg protease per kg NC diet significantly increased the villus height of duodenum, jejunum, and ileum when compared with the NC group (P < 0.05). Inclusions of 100 mg protease per kg NC diet also significantly increased the villus height of ileum when compared with the NC group (P < 0.05). Piglets in the PC group had lower crypt width of ileum when compared with the NC group (P < 0.05). There were no significant differences in the crypt width of duodenum and jejunum between the PC and NC groups (P > 0.05). Inclusions of 200 and 300 mg protease per kg NC diet significantly reduced the crypt width of duodenum and ileum when compared with the NC group (P < 0.05). Inclusions of 200 and 300 mg protease per kg NC diet significantly increased the VH:CD of duodenum, jejunum and ileum when compared with the NC group (P < 0.05).

Table 6.

Effect of protease supplementation on the morphology of small intestine of weaned piglets.

| Item | Site | PC | NC | Protease supplementation, mg/kg NC as fed basis |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 200 | 300 | ||||

| Villus height, μm | Duodenum | 345.13 ± 31.57a | 316.84 ± 25.46b | 328.19 ± 25.79ab | 350.20 ± 19.28a | 343.46 ± 24.01a |

| Jejunum | 339.46 ± 23.29a | 304.36 ± 30.45b | 320.07 ± 23.91ab | 342.52 ± 26.03a | 346.87 ± 21.85a | |

| Ileum | 331.55 ± 16.82a | 320.62 ± 25.41b | 330.41 ± 19.66a | 333.86 ± 20.59a | 329.15 ± 18.06a | |

| Crypt depth, μm | Duodenum | 299.31 ± 21.60ab | 305.34 ± 24.08a | 292.92 ± 17.95ab | 282.24 ± 22.99b | 275.83 ± 25.58b |

| Jejunum | 289.04 ± 18.58 | 295.50 ± 20.00 | 288.35 ± 19.95 | 283.07 ± 20.26 | 288.89 ± 21.52 | |

| Ileum | 285.15 ± 20.20b | 306.89 ± 19.15a | 284.96 ± 19.90b | 284.36 ± 20.03b | 278.92 ± 17.24b | |

| VH:CD | Duodenum | 1.15 ± 0.10ab | 1.04 ± 0.13b | 1.12 ± 0.03ab | 1.24 ± 0.02a | 1.25 ± 0.08a |

| Jejunum | 1.17 ± 0.05ab | 1.03 ± 0.05b | 1.11 ± 0.06b | 1.21 ± 0.05a | 1.20 ± 0.04a | |

| Ileum | 1.16 ± 0.04a | 1.04 ± 0.09b | 1.16 ± 0.02a | 1.17 ± 0.01a | 1.18 ± 0.12a | |

PC = positive control diet; NC = negative control diet; VH:CD = the ratio of villus height to crypt depth.

a,b Within a row, means without a common superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05), n = 6.

As shown in Table 7, the PC group had lower BUN and DAO in the plasma when compared with the NC group (P < 0.05). The PC group had higher total protein, albumin, and globulin in the plasma when compared with the NC group (P < 0.05). Inclusions of 200 and 300 mg protease per kg NC diet reduced the concentrations of BUN and DAO and increased the concentrations of TP in the plasma when compared with the NC group (P > 0.05). There were no significant differences in glucose and albumin to globulin ratio among all groups (P > 0.05).

Table 7.

Effects of dietary supplementation of protease on blood biochemical characteristics of weaned piglets.

| Item | PC | NC | Protease supplementation, mg/kg NC as fed basis |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 200 | 300 | |||

| Glucose, mmol/L | 5.95 ± 0.55 | 5.42 ± 0.89 | 5.6 ± 0.74 | 5.78 ± 0.43 | 5.68 ± 0.69 |

| Blood urea nitrogen, mmol/L | 4.37 ± 0.74b | 5.17 ± 0.66a | 4.66 ± 0.58ab | 4.21 ± 0.53b | 4.35 ± 0.26b |

| Total protein, g/L | 51.85 ± 4.59a | 44.15 ± 3.70c | 46.13 ± 3.88bc | 49.28 ± 4.21ab | 48.59 ± 4.42ab |

| Albumin, g/L | 29.05 ± 2.38a | 25.75 ± 2.42b | 26.68 ± 1.95ab | 28.59 ± 2.31a | 27.58 ± 2.32ab |

| Globulin, g/L | 22.80 ± 2.25a | 18.4 ± 2.34b | 19.45 ± 1.92b | 20.69 ± 1.96ab | 21.01 ± 2.12ab |

| Albumin: globulin ratio | 1.27 ± 0.22 | 1.4 ± 0.21 | 1.37 ± 0.18 | 1.38 ± 0.24 | 1.31 ± 0.19 |

| Diamine oxidase, IU | 4.03 ± 0.47b | 5.21 ± 0.45a | 4.58 ± 0.42ab | 4.13 ± 0.38b | 4.26 ± 0.51b |

PC = positive control diet; NC = negative control diet.

a,b,c Within a row, means without a common superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05), n = 6.

As shown in Fig. 1, the PC group had a higher peptide transporter 1 (PepT1) mRNA abundance in duodenum when compared with the NC group (P < 0.05). Inclusions of 100, 200, 300 mg protease per kg NC diet increased the PepT1 mRNA abundance in duodenum when compared with the NC group (P < 0.05). However, there were no significant differences of the PepT1 mRNA abundance in duodenum between the PC group and the groups provided with protease (P > 0.05). There were no significant differences of PepT1 mRNA abundance in jejunum and ileum among the all groups (P > 0.05). As shown in Fig. 2, there were no significant differences of b0,+AT mRNA abundance in duodenum among all groups (P > 0.05). The PC group had a higher b0,+AT mRNA abundance in jejunum when compared with the NC group (P < 0.05). Inclusions of 200 and 300 mg protease per kg NC diet increased the b0,+AT mRNA abundance in jejunum and ileum when compared with the NC group (P < 0.05). However, there were no significant differences of the b0,+AT mRNA abundance in jejunum and ileum between the PC group and the groups provided with protease (P > 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Effects of dietary supplementation of protease on relative mRNA expression of peptide transporter 1 (PepT1) along longitudinal axis of intestine. All samples were normalized using 18S expression as an internal control in each real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Relative level of PepT1 mRNA were analyzed by the 2-ΔCt method. Bars that share a common superscript do not differ (P > 0.05). Data were presented at the means ± SE (n = 6), in arbitrary units. 1 = PC; 2 = NC; 3 = 100 mg/kg NC; 4 = 200 mg/kg NC; 5 = 300 mg/kg NC.

Fig. 2.

Effects of dietary supplementation of protease on relative mRNA expression of b0,+AT along longitudinal axis of intestine. All samples were normalized using 18S expression as an internal control in each real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Relative level of b0,+AT mRNA were analyzed by the 2-ΔCt method. Bars that share a common superscript do not differ (P > 0.05). Data were presented at the means ± SE (n = 6), in arbitrary units. 1 = PC; 2 = NC; 3 = 100 mg/kg NC; 4 = 200 mg/kg NC; 5 = 300 mg/kg NC.

4. Discussion and conclusion

The use of single exogenous protease in swine is relatively new compared with the applications in poultry (Simbaya et al., 1996, Adeola and Cowieson, 2011). In the present study, replacement of fishmeal by vegetable protein reduced the growth performance of piglets, the digestibility of crude protein, and digestive enzyme activities. These results were consistent with the previous study that dietary protein source affected post-weaning feed intake, gastric protein breakdown, digestive enzyme activities (Makkink et al., 1994). Protease additions improved nutrient utilization efficiency and growth performance. Our results showed that the majority of the measured variables responded to protease supplementation in a dose-dependent manner. This indicates that 200 mg protease per kg NC diet supplementation would be more economically feasible under the resent experimental condition. The results were consistent with the previous study that supplementation of a neutral protease in barley/wheat/soy-based diets improved feed efficiency (O'Doherty and Forde, 1999). However, no positive effects of protease supplementation on growth performance were found in the grower-finisher pigs (McAlpine et al., 2012a). This is likely due to the fact that digestive function is fully developed in the grower-finisher stage and it allows pigs to digest and utilize dietary energy and nutrients more efficiently. It has been reported that superior growth responses to enzymes in piglets weighing below 20 kg, but not in those weighing from 20 to 40 kg (Ngoc et al., 2011, Zhang et al., 2014). Therefore, efficacy of protease may be related to types and levels of proteases, growth stages and diet nature of pigs.

In the present study, protease additions improved the digestibility of crude protein but not dry matter and gross energy. The results were in agreement with previous studies (Guggenbuhl et al., 2012, McAlpine et al., 2012a). Protease alone increased the ileal digestibility of crude protein and amino acids in the weaned pig diets (Guggenbuhl et al., 2012). The use of protease enzyme alone increased the ileal N digestibility of the diet but had no effect on growth performance in grower-finisher pigs (McAlpine et al., 2012a). Therefore, dietary protease can improve the digestibility of crude protein and amino acids that may not necessarily lead to increased growth performance. Moreover, inclusion of protease may neutralize anti-nutritive factors such as protease inhibitors and then improve the digestibility of crude protein (Huo et al., 1993). In the present study, increased growth performance may be partially attributed to increased crude protein digestibility.

After weaning, it is well established that a dramatic decrease in the activity of digestive enzyme is observed in the stomach and pancreatic tissue (Hedemann and Jensen, 2004). So, it is necessary to include diary protease to complement endogenous proteolytic enzyme to digest nutrient more efficiently especially when lower digestible protein is included in the diet. In the present study, protease additions improved digestive enzyme activities in the gut. These results indicated that supplementing pig diets with protease may stimulate the synthesis of digestive enzymes, resulting in better digestion and improving growth performance that were observed in this present study.

Diamine oxidase is used as a marker of intestinal mucosal maturation and integrity (Luk et al., 1980). In the present study, replacement of fishmeal by vegetable protein impaired the intestinal morphology and increased BUN and DAO in the plasma, which were attenuated by protease. This is likely due to the fact that soybean meal contains allergens (β-conglycinin) that can cause allergic reaction to damage intestinal structure by depressing intestinal cell growth, damaging the cytoskeleton, and causing apoptosis in the piglets (Rooke et al., 1998, Hao et al., 2009, Chen et al., 2011). Inclusion of protease may degrade the allergens which come from soybean meal and then attenuate the allergic reactions to improve intestinal integrity, but this warrants further studies.

Diarrhea caused by nutritional factors and infectious disease is a serious problem around weaning and usually leads to impaired growth performance and even an increased mortality in piglets (Fairbrother et al., 2005). It is well established that supplementing enzymes can reduce diarrhea index (Heo et al., 2013). In the present study, we found protease additions also reduced the diarrhea index. This is probably due to the facts observed above: 1) improved intestinal development; 2) increased digestive enzyme activities; and 3) increased nutrient digestibility.

Uptake of amino acids in short peptide–bound form is a biological phenomenon found throughout nature, and a significant fraction of dietary amino N is absorbed as intact oligopetides rather than free amino acids (Ganapathy et al., 1994). Two peptide transporters, identified as PepT1 and PepT2 corresponding to SLC15A1 and SLC15A2, have been cloned and functionally characterized in several mammalian species in the past decade (Krehbiel and Matthews, 2003). Peptide transporter 1, predominantly expressed in the apical membrane of intestinal epithelial cells, has been shown to have nutritional importance and potential clinical and pharmaceutical applications (Chen et al., 2002, Daniel, 2004, Aito-Inoue et al., 2007). Intestinal amino acids transporters are responsible for absorption of amino acids across intestinal epithelial cells from the lumen into portal blood circulation and play major roles in whole body N metabolism during both absorptive and post-absorptive states (Christensen, 1990). b0,+AT is described as a Na+-independent transporter for transporting cationic and neutral amino acids into cells in exchange for intracellular neutral amino acids (Verrey et al., 2004). The abundance of peptide and amino acid transporter in the intestine is an important determinant of protein absorption efficiency. In the present study, protease additions increased the mRNA abundance of PepT1 in duodenum and the mRNA abundance of b0,+AT in jejunum and ileum. The results indicate protease additions might improve the absorption efficiency of peptide and amino acids. The increased mRNA abundance of PepT1 and b0,+AT may be mainly due to the availability of more peptides and amino acids released by protease in the gut.

In conclusion, dietary protease supplementation increased growth performance in weaned piglets, which may contribute to the improvement of intestinal development, protein digestibility, nutrient transport efficiency, and health status of piglets when they were fed low digestible protein source. Dietary protease supplementation in diets containing lower cost alternative ingredients may be a very promising way to reduce feed cost and make pork production more profitable. However, further investigations are required to understand interactions in digestive gut of pigs, with other supplemental enzymes and with dietary proteins.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by National Basic Research Program of China (2013CB127301), National Scientific and Technology Support Project (2013BAD21B04) and Guangdong Province Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No.S2013010013215).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

References

- Adeola O., Cowieson A.J. Opportunities and challenges in using exogenous enzymes to improve nonruminant animal production. J Anim Sci. 2011;89:3189–3218. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-3715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC International . 18th ed. AOAC International; Gaithersburg, MD: 2006. Official methods of analysis of AOAC international. [Google Scholar]

- Aito-Inoue M., Lackeyram D., Fan M.Z., Sato K., Mine Y. Transport of a tripeptide, Gly-Pro-Hyp, across the porcine intestinal brush-border membrane. J Pept Sci. 2007;13:468–474. doi: 10.1002/psc.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Pan Y.X., Wong E.A., Webb K.E., Jr. Characterization and regulation of a cloned ovine gastrointestinal peptide transporter (oPepT1) expressed in a mammalian cell line. J Nutr. 2002;132:38–42. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F., Hao Y., Piao X.S., Ma X., Wu G.Y., Qiao S.Y. Soybean-derived beta-conglycinin affects proteome expression in pig intestinal cells in vivo and in vitro. J Anim Sci. 2011;89:743–753. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen H.N. Role of amino acid transport and countertransport in nutrition and metabolism. Physiol Rev. 1990;70:43–77. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel H. Molecular and integrative physiology of intestinal peptide transport. Annu Rev Physiol. 2004;66:361–384. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032102.144149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbrother J.M., Nadeau E., Gyles C.L. Escherichia coli postweaning diarrhea in pigs: an update on bacterial types, pathogenesis, and prevention strategies. Anim Health Res Rev. 2005;6:17–39. doi: 10.1079/ahr2005105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan C.L., Han X.Y., Xu Z.R., Wang L.J., Shi L.R. Effects of β-glucanase and xylanase supplementation on gastrointestinal digestive enzyme activities of weaned piglets fed a barley-based diet. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 2009;93:271–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0396.2008.00816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganapathy V., Brandsch M., Leibach F.H. Intestinal transport of amino acids and peptides. In: Johnson L.R., editor. Physiology of the gastrointestinal tract. 3rd ed. Raven Press; New York: 1994. pp. 1773–1794. [Google Scholar]

- Guggenbuhl P., Waché Y., Wilson J.W. Effects of dietary supplementation with a protease on the apparent ileal digestibility of the weaned piglet. J Anim Sci. 2012;90:152–154. doi: 10.2527/jas.53835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Y., Zhan Z.F., Guo P.F., Piao X.S., Li D.F. Soybean β-conglycinin-induced gut hypersensitivity reaction in a piglet model. Arch Anim Nutr. 2009;63:188–204. [Google Scholar]

- Hedemann M.S., Jensen B.B. Variations in enzyme activity in stomach and pancreatic tissue and digesta in piglets around weaning. Arch Anim Nutr. 2004;58:47–59. doi: 10.1080/00039420310001656677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo J.M., Opapeju F.O., Pluske J.R., Kim J.C., Hampson D.J., Nyachoti C.M. Gastrointestinal health and function in weaned pigs: a review of feeding strategies to control post-weaning diarrhoea without using in-feed antimicrobial compounds. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutri. 2013;97:207–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0396.2012.01284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoda N., Nishi M., Nakagawa M., Hiramatsu Y., Hioki K., Yamamoto M. Structural and functional alterations in the gut of parenterally or enterally fed rats. J Surg Res. 1989;47:129–133. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(89)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo G.C., Fowler V.R., Bedford M. The use of enzymes to denature antinutritive factors in soybean. In: van der Poel A.F.B., Huisman J., Saini H.S., editors. Recent advances of research in antinutritional factors in legume seeds. Proceedings of the Second International Workshop on ‘Antinutritional factors (ANFs) in Legume seeds’. Wageningen Pers; Wageningen, The Netherlands: 1993. pp. 517–521. [Google Scholar]

- Ji F., Casper D.P., Brown P.K., Spangler D.A., Haydon K.D., Pettigrew J.E. Effects of dietary supplementation of an enzyme blend on the ileal and fecal digestibility of nutrients in growing pigs. J Anim Sci. 2008;86:1533–1543. doi: 10.2527/jas.2007-0262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo J.K., Ingale S.L., Kim J.S., Kim Y.W., Kim K.H., Lohakare J.D. Effects of exogenous enzyme supplementation to corn- and soybean meal-based or complex diets on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, and blood metabolites in growing pigs. J Anim Sci. 2012;90:3041–3048. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-3430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krehbiel C.R., Matthews J.C. Absorption of amino acids and peptides. In: D'Mello J.P.F., editor. Amino acids in animal nutrition. 2nd ed. CAB Int; Wallingford, UK: 2003. pp. 41–70. [Google Scholar]

- Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time PCR quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk G.D., Bayless T.M., Baylin S.B. Diamine oxidase (histaminase). A circulating marker for rat intestinal mucosal maturation and integrity. J Clin Invest. 1980;66:66–70. doi: 10.1172/JCI109836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makkink C.A., Negulescu G.P., Qin G., Verstegen M.W. Effect of dietary protein source on feed intake, growth, pancreatic enzyme activities and jejunal morphology in newly-weaned piglets. Br J Nutr. 1994;72:353–368. doi: 10.1079/bjn19940039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlpine P.O., O'Shea C.J., Varley P.F., O'Doherty J.V. The effect of protease and xylanase enzymes on growth performance and nutrient digestibility in finisher pigs. J Anim Sci. 2012;90:375–377. doi: 10.2527/jas.53979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlpine P.O., O'Shea C.J., Varley P.F., Solan P., Curran T., O'Doherty J.V. The effect of protease and nonstarch polysaccharide enzymes on manure odor and ammonia emissions from finisher pigs. J Anim Sci. 2012;90:369–371. doi: 10.2527/jas.53948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngoc T.T.B., Len N.T., Ogle B., Lindberg J.E. Influence of particle size and multi-enzyme supplementation of fibrous diets on total tract digestibility and performance of weaning (8–20 kg) and growing (20–40 kg) pigs. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2011;169:86–95. [Google Scholar]

- Nutrient requirements for swine (NRC) 11th ed. Academic Press; Washington, DC, USA: 2012. NRC. [Google Scholar]

- Omogbenigun F.O., Nyachoti C.M., Slominski B.A. Dietary supplementation with mutienzyme preparations improves nutrient utilization and growth performance in weaned pigs. J Anim Sci. 2004;82:1053–1061. doi: 10.2527/2004.8241053x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Doherty J.V., Forde S. The effect of protease and alpha-galactosidase supplementation on the nutritive value of peas for growing and finishing swine. Ir J Agric Food Res. 1999;38:217–226. [Google Scholar]

- Rooke J.A., Slessor M., Fraser H., Thomson J.R. Growth performance and gut function of piglets weaned at four weeks of age and fed protease-treated soybean meal. Anim Feed Sci Tech. 1998;70:175–190. [Google Scholar]

- Schmit T.M., Verteramo L., Tomek W.G. Implications of growing biofuel demands on northeast livestock feed costs. Agric Resour Econ Rev. 2009;38:200–212. [Google Scholar]

- Simbaya J., Slominski B.A., Guenter W., Morgan A., Campbell L.D. The effects of protease and carbohydrase sup- plementation on the nutritive value of canola meal for poul-try: In vivo and in vitro studies. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 1996;61:219–234. [Google Scholar]

- Tietz N.W., Fiereck E.A. A specific method for plasma lipase determination. Clin Chim Acta. 1966;13:352–358. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(66)90215-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verrey F., Closs E., Wagner C., Palacin M., Endou H., Kanai Y. CATs and HATs: the SLC7 family of amino acid transporters. Pflüeg Arch. 2004;447:532–542. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1086-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y.L., Baidoo S.K., Jin L.Z., Liu Y.G., Schulze H., Simmins P.H. The effect of different carbohydrase and protease supplementation on apparent (ileal and overall) digestibility of nutrients of five hulless barley varieties in young pigs. Livestock Pro Sci. 2001;71:109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y.L., Deng Z.Y., Huang H.L., Li T.J., Zhong H.Y. The effect of arabinoxylanase and protease supplementation on nutritional value of diets containing wheat bran or rice bran in growing pig. J Anim Feed Sci. 2004;13:445–461. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G.G., Yang Z.B., Wang Y., Yang W.R., Zhou H.J. Effect of dietary supplementation of muti-enzyme on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, small intestinal digestive enzyme activities, and large intestinal selected microbiota in weanling pigs. J Anim Sci. 2014;92:2063–2069. doi: 10.2527/jas.2013-6672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]