Abstract

This study investigated the effects of protein sources for milk replacers on growth performance and serum biochemical indexes of suckling calves. Fifty Chinese Holstein bull calves with similar BW and age were randomly allocated to 5 groups (1 control and 4 treatments) of 10 calves in each group. Five types of milk replacers were designed to have the same level of energy and protein. The protein source for milk replacers of the control group was full milk protein (MP). The protein source of milk replacers of the 4 treatment groups was composed of MP and one vegetable protein (VP) (30 and 70% of total protein). The 4 types of VP were soybean protein concentrate (SP), hydrolyzed wheat protein (WP), peanut protein concentrate (PP), and rice protein isolate (RP). Results of the experiment showed: 1) there was no significant difference on average daily gain (ADG) and feed:gain ratio (F:G) among the MP, SP and RP groups (P > 0.05), whereas the ADG and F:G of the WP and PP groups were significantly lower compared with the MP group (P < 0.05); 2) there was not a significant difference in withers height, body length and heart girth among treatment groups compared with the MP group (P > 0.05). Thereby the 4 VP milk replacers had no adverse effects on body size of calves; 3) all groups showed no significant difference in the serum contents of urea nitrogen, total protein, albumin, globulin, β-hydroxybutyrate, growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor-1, and the ratio of albumin to globulin (A:G) (P > 0.05). In conclusion, SP or RP (accounts for 70% of the total protein) as calf milk replacers could substitute MP, whereas wheat gluten and PP had a significant adverse effect on growth performance in this experiment.

Keywords: Calf, Growth performance, Milk replacer, Milk protein replacement, Serum biochemical parameters, Vegetable protein

1. Introduction

Using milk replacers to feed early-weaned calves is an effective way to raise replacement cattle in modern dairy industry (Heinrichs, 1993). Protein is one of the most important nutrients in milk replacers, and choosing appropriate protein sources becomes an important factor affecting feedstuff quality and animal production costs (Erickson et al., 1989). Protein sources usually used as milk replacers fall into two types: milk protein (MP) and non-milk protein. Milk protein is an excellent protein source as a milk replacer because it has balanced amino acid constituents, a low level of anti-nutritional factors, and a high digestibility value. However, China has a relative shortage of MP source as a result of a high demand for dairy products, which keeps MP price high. Research has showed soybean protein as a protein source for milk replacers to be comparable to MP on growth performance of suckling calves (Lalles et al., 1995, Tomkins et al., 1994a, Tomkins et al., 1994b. Furthermore, the nutritional value of vegetable proteins (VP) from wheat, peanut and rice is similar to that of soybean protein, and China produces considerable amounts of these crops. Thus, exploring the potential of these VP will open up novel sources of milk replacers. Studies on protein sources for milk replacers in the past focused mainly on adding low levels of soybean protein (replacement level lower than 50% crude protein). Using high levels of VP as milk replacers (replacement level higher than 50%) has rarely been reported.

This study tested 4 types of VP as main protein sources of milk replacers with the main essential amino acids in relative balance. Growth performance and serum biochemical indexes of suckling calves were studied.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Experimental animals

The experiment was conducted at Zhuochen Livestock Co. Ltd., Beijing. Fifty Holstein bull calves (21 ± 6 d, 46 ± 6 kg) with similar age and BW were selected and randomly allocated to 5 groups of 10 calves per group.

2.2. Experiment design and diets

In this experiment, a single-factor completely randomized design was used to study the effects of different VP sources on calves. These VP sources were soybean protein concentrate (SP), hydrolyzed wheat protein (WP), peanut protein concentrate (PP), and rice protein isolate (RP). Five milk replacers were formulated using 30% MP and 70% VP. The milk replacers used in this experiment had the same CP (22%), GE (19.66 MJ/kg), Lys (1.84%), and Lys:Met:Thr:Trp ratio (100:29.5:65:20.5). The amino acid levels of the milk replacers were adjusted by adding crystalline amino acids to the basal ration. Calves in the controlled group (MP) were fed a full MP milk replacer. Calves in treatment groups were fed 4 types of VP milk replacers, which were derived from SP (CP = 65.2%), WP (CP = 77.8%), PP (CP = 54.7%) and RP (CP = 82.0%). All calves in this experiment were fed the same starter up to 42 days of age. The nutrient levels and composition of milk replacers and starter in this experiment are shown in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Nutrient composition (%) of milk replacers (air dry matter basis).1

| Item | Milk replacers |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP | SP | WP | PP | RP | |

| DM | 96.26 | 95.50 | 95.75 | 95.46 | 96.36 |

| CP | 22.71 | 22.44 | 21.64 | 21.76 | 22.31 |

| DE, MJ/kg2 | 18.26 | 17.04 | 16.78 | 16.29 | 17.03 |

| EE | 14.43 | 15.15 | 15.14 | 14.99 | 14.76 |

| Ash | 6.68 | 5.20 | 4.06 | 5.02 | 4.31 |

| Ca | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.74 |

| P | 0.66 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.54 |

MP = milk protein; SP = soybean protein concentrate; WP = hydrolyzed wheat protein; PP = peanut protein concentrate; RP = rice protein insolate; DM = dry matter; CP = crude protein; DE = digestible energy; EE = ether extract.

All data in this table were measured values.

Digestible energy (DE) = K × GE, where the K values were measured by digestion and metabolism experiments in this study, GE = gross energy.

Table 2.

Ingredients and nutrient composition of the starter (air dry matter basis).

| Item | Content |

|---|---|

| Ingredients, % | |

| Corn | 44.3 |

| Soybean meal | 23.8 |

| Wheat bran | 5.0 |

| DDGS | 10.0 |

| Extruded soybean | 4.9 |

| Extruded corn | 5.0 |

| Cottonseed meal | 3.0 |

| Calf premix1 | 4.0 |

| Nutrient composition, %2 | |

| DM | 89.39 |

| CP | 21.18 |

| DE, MJ/kg3 | 12.62 |

| EE | 2.03 |

| Ash | 6.53 |

| Ca | 0.72 |

| P | 0.50 |

DDGS = distillers dried grains with soluble; DM = dry matter; CP = crude protein; DE = digestible energy; EE = ether extract.

The calf premix provided the following per kg of diets: VA 15,000 IU, VD 5,000 IU, VE 50 mg, VK3 4 mg, VB1 8 mg, VB2 7.2 mg, VB5 80 mg, VB6 8 mg, VB12 0.04 mg, biotin 0.60 mg, folic acid 4.0 mg, nicotinic acid 20 mg, Fe (as ferrous sulfate) 90 mg, Cu (as copper sulfate) 12.5 mg, Mn (as manganese sulfate) 30 mg, Zn (as zinc sulfate) 90 mg, Se (as sodium selenite) 0.3 mg, I (as potassium iodide) 1.0 mg, Co (as cobalt chloride) 0.5 mg.

All results were measured values.

DE (%)= 4.184 × 0.7 × [(0.057 × CP%) + (0.092 × EE%) + (0.0415 × carbohydrates%)], where carbohydrates % = 100 – EE% – CP% – Ash%, from NRC 2001.

2.3. Feeding management

All selected calves were fed 3 L colostrum within 1.5 h after birth. Twelve hours after birth, they were fed colostrum and ordinary milk, which amounted to 10% of their BW, by an esophageal feeder. The transitional period of milk replacer was from 15 to 20 days of age. The ratio of milk to milk replacer (3:1) gradually decreased to 1:3 during the transitional period, and eventually to 0:1 on 21 days of age.

One portion of milk replacer was completely dissolved into 7 portions of warm water (wt/wt) which had been boiled and then cooled to 40 to 50°C. The calves were fed the milk replacers twice daily (0800 and 1830) using individual bowls. All calves had ad libitum access to water 0.5 h after feeding. Milk replacer allowance per day per calf was 100 g/kg BW, and the amount was adjusted as their BW increased.

With restricted feeding, the daily dry matter intake (DMI) of a starter calf was set at 400 g during weeks 4 to 5, and was set at 800 g in week 6. Each calf was housed in a 2.25 m2 single pen. In order to ensure calf health, lime was used to disinfect the pen once a week.

2.4. Sample collection and analysis

2.4.1. Measurement of DMI, BW, and body size

The amounts of milk replacer and starter that were supplied and remained were accurately recorded daily. The milk replacer and starter feed were sampled before morning meals daily. Feed samples of each group were collected and thoroughly mixed, and average daily intake was calculated every week.

Calves were weighed weekly and the body sizes (withers height, heart girth and body length) were determined every 2 weeks prior to morning meals during the experiment period.

2.4.2. Blood serum sample collection

From week 3, four calves per each group were selected for blood serum sampling per 2 weeks prior to morning meals. An 8-mL blood sample was taken from the jugular vein and then stood in vacuum centrifuge tube at room temperature for 30 min. The blood serum was acquired by centrifugation at 1,485 × g for 20 min and immediately stored at −20°C.

2.4.3. Sample determination

Samples of milk replacers and starter were analyzed for dry matter (DM), total CP, ash, total P, total Ca (AOAC, 1980), and total ether extract (EE) by supercritical fluid extraction (TFE 2000 Leco Fat Extractor, St. Joseph, MI), and gross energy (GE) by bomb calorimeter (Parr 6300 Automatic Bomb Calorimeter, Parr Instrument Company, Moline, IL). The content of total protein (TP), albumin, globulin, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), β-hydroxybutyric acid (β-HB) in blood sera was determined using the standard kit (Biosino bio-technology and science incorporation) by biochemical analyzer (Model 7600; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). The contents of growth hormone (GH) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) in blood sera were determined according to the radioimmunoassay kit.

2.4.4. Statistical analysis

We carried out the statistical analysis using the model of MIXED and ANOVA in SAS 9.2 to test P-value and SEM. The difference was considered to be significant when the P-value was less than 0.05.

3. Results and analyses

3.1. Growth performance

3.1.1. Dry matter intake and feed conversion ratio

Table 3 shows that no significant difference for DMI of the starter exists among groups from 22 to 56 days (P > 0.05), and it was significantly higher for the SP and RP groups than for other groups from 57 to 63 days (P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Dry matter intakes (DMI) of the starter and feed:gain ratios (F:G) of control and vegetable protein groups.

| Item | Group |

SEM |

P-value |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP | SP | WP | PP | RP | Treatment | Day | Treatment × Day | ||

| Starter DMI, g/d | |||||||||

| d 22 to 63 | 695.2 | 680.2 | 660.6 | 670.6 | 738.9 | 16.55 | 0.7308 | <0.0001 | 0.8462 |

| d 22 to 28 | 380.0 | 380.0 | 380.0 | 385.0 | 398.6 | 27.96 | 0.8413 | ||

| d 29 to 35 | 487.1 | 468.6 | 448.6 | 442.1 | 463.6 | 7.45 | 0.0612 | ||

| d 36 to 42 | 535.7 | 517.9 | 516.4 | 510.7 | 535.7 | 4.67 | 0.0936 | ||

| d 43 to 49 | 748.6 | 773.6 | 730.7 | 780.0 | 869.3 | 36.14 | 0.2429 | ||

| d 50 to 56 | 882.1 | 961.4 | 885.0 | 842.1 | 985.7 | 36.59 | 0.2303 | ||

| d 57 to 63 | 893.6b | 1,054.3a | 895.7b | 874.3b | 1,071.4a | 28.14 | 0.0226 | ||

| F:G, g/g | |||||||||

| d 22 to 63 | 1.79b | 2.05b | 2.20ab | 2.47a | 2.03b | 0.028 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.9999 |

| d 22 to 28 | 2.04b | 2.13b | 2.27ab | 2.55a | 2.12b | 0.075 | 0.0062 | ||

| d 29 to 35 | 1.73b | 2.03ab | 2.23a | 2.36a | 2.11a | 0.062 | 0.0008 | ||

| d 36 to 42 | 1.72b | 1.79b | 2.01ab | 2.22a | 1.86ab | 0.063 | 0.0078 | ||

| d 43 to 49 | 1.56b | 1.78b | 1.90ab | 2.22a | 1.80b | 0.050 | 0.0005 | ||

| d 50 to 56 | 2.03b | 2.31b | 2.46ab | 2.70a | 2.23b | 0.068 | 0.0004 | ||

| d 57 to 63 | 1.90c | 2.30b | 2.36ab | 2.71a | 2.29b | 0.066 | <0.0001 | ||

MP = milk protein; SP = soybean protein concentrate; WP = hydrolyzed wheat protein; PP = peanut protein concentrate; RP = rice protein insolate; SEM = standard error of mean; F:G = feed:gain ratio.

a,b Within a same row, mean with the same or no superscripts differ not significantly (P > 0.05), means with different superscripts differ significantly (P < 0.05), n = 10.

Table 3 also indicates that the ratio of feed to gain (F:G) was significantly higher for the PP group than for the MP group (control group) from 22 to 63 days (P < 0.05), and F:G was significantly higher for the PP group than for the SP group during the whole experiment period except from 29 to 35 days (P < 0.05), and F:G was significantly higher for the RP group than for the PP group during the whole experiment period except from 29 to 42 days (P < 0.05).

3.1.2. Weight gain

Table 4 shows no significant differences existed for initial BW among all groups on day 21 with average BW 45.2 kg (P > 0.05). From 22 to 28 days, no significant difference existed for average daily gain (ADG) among all groups (P > 0.05); form 29 to 35 days, groups showed the following sequence: MP > SP > RP > WP > PP in terms of ADG and the MP group had a significantly superior ADG than the WP, PP, RP groups (P < 0.05); from 36 to 42 days, the PP group had a significantly inferior ADG than the MP, SP, RP groups, and the WP group had a significantly inferior ADG than the MP group (P < 0.05), and differences for ADG were not significantly different among the SP, RP, and MP groups (P > 0.05); ADG of all groups showed similar patterns for the following 4 periods: 36 to 42 days, 43 to 49 days, 50 to 56 days, and 57 to 63 days.

Table 4.

Body weight (BW) and average daily gain (ADG) of control and vegetable protein groups.

| Item | Group |

SEM |

P-value |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP | SP | WP | PP | RP | Treatment | Day | Treatment × Day | ||

| Initial BW, kg | |||||||||

| d 21 | 44.8 | 45.2 | 45.2 | 44.9 | 45.3 | 0.74 | 0.8775 | ||

| ADG, g/d | |||||||||

| d 22 to 63 | 775.6 | 698.2 | 626.7 | 554.2 | 711.6 | 13.39 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.9870 |

| d 22 to 28 | 516.3 | 485.0 | 442.5 | 400.0 | 510.0 | 28.34 | 0.2089 | ||

| d 29 to 35 | 651.3a | 552.5ab | 490.0bc | 447.5c | 537.5b | 18.36 | 0.0003 | ||

| d 36 to 42 | 741.7a | 680.0ab | 593.3bc | 523.3c | 663.3ab | 22.94 | 0.0021 | ||

| d 43 to 49 | 1,016.3a | 892.5ab | 820.0bc | 722.5c | 937.5ab | 32.52 | 0.0038 | ||

| d 50 to 56 | 888.6a | 825.7ab | 742.9bc | 657.1c | 862.9ab | 22.38 | 0.0005 | ||

| d 57 to 63 | 965.7a | 874.3ab | 774.3bc | 662.9c | 874.3ab | 21.76 | <0.0001 | ||

MP = milk protein; SP = soybean protein concentrate; WP = hydrolyzed wheat protein; PP = peanut protein concentrate; RP = rice protein insolate; SEM = standard error of mean; ADG = average daily gain.

a,b,c Within a row, means with same or no superscripts differ not significantly (P > 0.05), means with different superscripts differ significantly (P < 0.05).

3.2. Body size indexes

Table 5 shows no significant differences existed for withers height, body length and heart girth among groups from 21 to 63 days (P > 0.05). All body size indexes significantly increased with age (P < 0.01). There was no significant interaction between treatments and age for body height, body length and heart girth among all groups (P > 0.05).

Table 5.

Body sizes of control and vegetable protein groups.

| Item | Groups |

SEM |

P-value |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP | SP | WP | PP | RP | Treatment | Day | Treatment × Day | ||

| Withers height, cm | |||||||||

| d 21 to 63 | 81.4 | 82.8 | 80.9 | 81.1 | 81.5 | 0.343 | 0.7873 | <0.0001 | 0.7079 |

| d 21 | 77.3 | 79.1 | 77.5 | 77.1 | 77.4 | 0.495 | 0.2874 | ||

| d 35 | 78.9 | 80.7 | 79.4 | 79.5 | 79.4 | 0.423 | 0.2847 | ||

| d 49 | 83.3 | 84.5 | 81.7 | 82.7 | 82.8 | 0.509 | 0.1007 | ||

| d 63 | 86.1 | 86.9 | 85.1 | 85.4 | 86.3 | 0.625 | 0.2768 | ||

| Body length, cm | |||||||||

| d 21 to 63 | 78.0 | 78.0 | 77.5 | 77.7 | 77.5 | 0.352 | 0.9950 | <0.0001 | 0.3571 |

| d 21 | 73.4 | 74.2 | 73.5 | 74.6 | 72.7 | 0.402 | 0.2690 | ||

| d 35 | 75.7 | 76.2 | 75.4 | 76.1 | 76.2 | 0.443 | 0.6448 | ||

| d 49 | 80.1 | 79.4 | 79.0 | 78.5 | 79.4 | 0.588 | 0.3964 | ||

| d 63 | 82.7 | 82.3 | 82.0 | 81.3 | 81.9 | 0.689 | 0.4288 | ||

| Heart girth, cm | |||||||||

| d 21 to 63 | 88.8 | 88.4 | 87.7 | 87.1 | 88.1 | 0.419 | 0.9602 | <0.0001 | 0.7754 |

| d 21 | 79.7 | 80.5 | 80.2 | 79.5 | 78.9 | 0.519 | 0.4381 | ||

| d 35 | 86.9 | 86.8 | 85.4 | 85.5 | 85.7 | 0.582 | 0.4678 | ||

| d 49 | 91.4 | 91.0 | 91.0 | 89.8 | 92.3 | 0.731 | 0.2230 | ||

| d 63 | 97.4 | 95.3 | 94.4 | 93.6 | 95.4 | 0.820 | 0.3663 | ||

MP = milk protein; SP = soybean protein concentrate; WP = hydrolyzed wheat protein; PP = peanut protein concentrate; RP = rice protein insolate; SEM = standard error of mean.

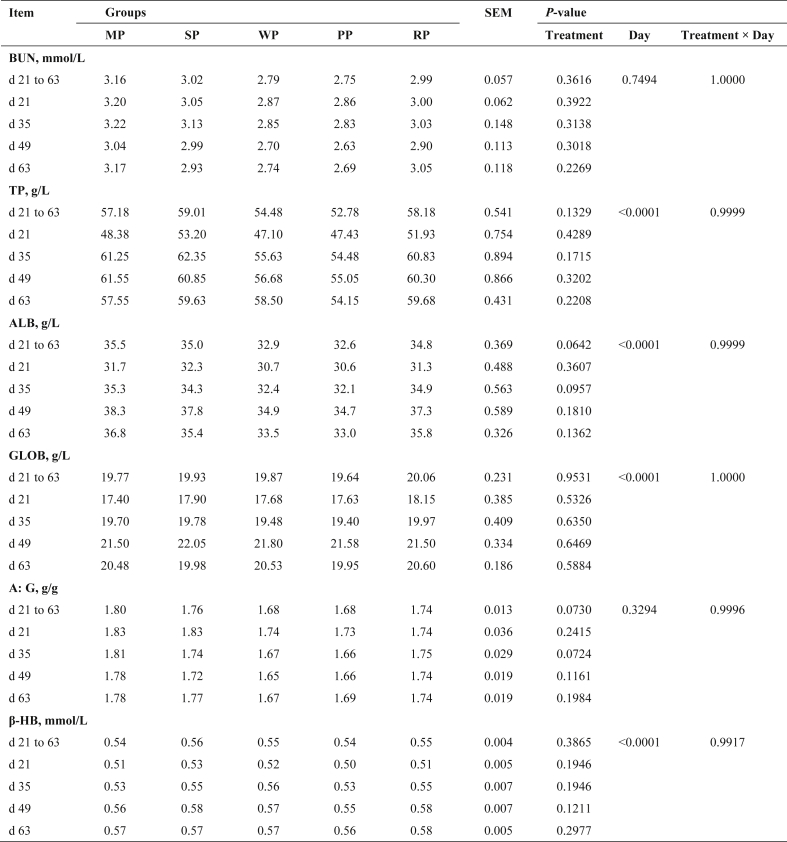

3.3. Serum biochemical indexes

Table 6 shows the change of serum BUN with age was not significant for all groups (P > 0.05), it showed a tendency to ascend and then to descend for all groups and it was significantly lower for the WP and PP groups than for the other 3 groups during the whole experiment period, and it was significantly lower for the PP group than for the MP and SP groups on day 35 (P > 0.05). The age had a significant influence on the level of TP in blood sera (P > 0.05) and no significant differences were shown among groups (P > 0.05), and the average TP concentrations of the WP and PP groups, 54.48 and 52.78 g/L respectively, were less than 57.18 g/L of the MP group. The effects of age on the level of ALB in the blood sera were not significant (P > 0.05), and differences among groups were not significant (P > 0.05) during the whole experiment period. The ALB concentrations of all groups showed a tendency to decline at first and then to rise gradually with age which is similar to TP. Results of statistical analysis showed the level of β-HB in sera significantly increased with age (P < 0.05), whereas the effects of protein sources on the β-HB concentration in sera of calves were not significant for all groups (P > 0.05).

Table 6.

Serum metabolite contents of control and vegetable protein groups.

MP = milk protein; SP = soybean protein concentrate; WP = hydrolyzed wheat protein; PP = peanut protein concentrate; RP = rice protein insolate; SEM = standard error of mean; BUN = serum urea nitrogen; TP = total protein; ALB = albumin; GLOB = globulin; A: G = the ratio of albumin to globulin; β-HB = β-hydroxybutyrate.

3.4. Concentrations of hormones

As Table 7 shows, age had a significant impact on the level of GH, IGF-1 in the sera of calves in all groups (P > 0.05). The concentrations of GH, IGF-1 showed a same tendency to decline (21 to 35 days) and then to rise (35 to 49 days) and then to decline (49 to 63 days). During the whole experiment period, the levels of GH and IGF-1 showed no significant differences among all groups (P > 0.05), but the levels of the WP and PP groups were slightly less than those of the MP group.

Table 7.

Concentrations of growth hormone (GH) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) of control and vegetable protein groups.

| Item | Groups |

SEM |

P-value |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP | SP | WP | PP | RP | Treatment | Day | Treatment × Day | ||

| GH, ng/mL | |||||||||

| d 21 to 63 | 3.46 | 3.37 | 3.08 | 3.14 | 3.31 | 0.078 | 0.4824 | 0.0107 | 0.9914 |

| d 21 | 3.04 | 3.27 | 3.02 | 3.16 | 3.11 | 0.157 | 0.6148 | ||

| d 35 | 2.95 | 3.07 | 2.82 | 2.98 | 3.01 | 0.140 | 0.6118 | ||

| d 49 | 4.04 | 3.77 | 3.43 | 3.44 | 3.87 | 0.155 | 0.2200 | ||

| d 63 | 3.81 | 3.37 | 3.07 | 2.96 | 3.27 | 0.125 | 0.0896 | ||

| IGF-1, ng/mL | |||||||||

| d 21 to 63 | 210.61 | 211.51 | 203.09 | 198.77 | 204.53 | 3.963 | 0.9308 | 0.025 | 0.9704 |

| d 21 | 210.47 | 223.44 | 233.76 | 224.13 | 212.29 | 7.989 | 0.3768 | ||

| d 35 | 209.10 | 207.18 | 186.73 | 181.24 | 202.76 | 6.890 | 0.6712 | ||

| d 49 | 217.46 | 219.15 | 215.13 | 203.42 | 210.31 | 8.149 | 0.4149 | ||

| d 63 | 205.41 | 196.29 | 176.73 | 186.31 | 192.76 | 7.372 | 0.6521 | ||

MP = milk protein; SP = soybean protein concentrate; WP = hydrolyzed wheat protein; PP = peanut protein concentrate; RP = rice protein insolate; SEM = standard error of mean; GH = growth hormone; IGF-1 = insulin-like growth factors-1.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of protein sources for milk replacers on the growth performance of suckling calves

Different VP sources and proportions for milk replacers had different effects on the growth performance of suckling calves (Drackley and Davis, 1998). Using unprocessed full-fat soybean powder in milk replacer significantly reduced the growth performance of calves (Smith and Sissons, 1975). However, SP, soybean protein isolated and rumen fermentative soybean flour as the main protein sources for milk replacers were equivalent to MP in gaining calf growth rate (Lalles et al., 1995). Hill et al. (2008) used wheat gluten and rice protein concentrate (CP content 80%) as protein sources for calf diets to substitute MP, and their result showed, as the proportions of VP continuously increased, ADG continuously declined. Li et al. (2008) used soybean protein as a protein source for milk replacers to provide 20, 50, 80% of total dietary protein, and reported that BW gain showed a downward trend as the soybean protein proportion increased during the whole experimental period. Tomkins et al., 1994a, Tomkins et al., 1994b also indicated that, although effects of the utilization of VP was not very ideal for 2-week-old calves, the ADG of calves in VP group was only 6.4% lower than that in the full MP group during a 6-week test period. The present study indicated that the 4 VP had biggish differences in affecting the growth performance of suckling calves compared with MP, and this had a direct relationship with different protein sources.

The SP and RP groups showed growth performance similar to that of the MP group. However, the WP and PP groups showed lower growth performance than the MP group. The starter intakes were significant higher in the SP and RP groups than in the MP group from 50 to 63 days, the reason could be that the rumens of calves in the SP and RP groups were fully developed in this period. It was in accordance with the report of Lesmeister and Heinrichs (2004) that feeding milk replacers from MP source was beneficial for rumen and reticulum development of calves. During the whole experiment period, the 4 groups of VP had better performance for F:G but worse performance for ADG, and the SP, WP, RP groups showed no significant differences in F:G, but the PP group had significant higher F:G compared with the MP group. The 5 types of milk replacer in this experiment were formulated to have a same protein level using a same amino acid model, thus it virtually eliminated effects of nutrient levels on the growth performance of calves. The favorable growth performance of the SP and RP groups indicated that soybean and rice were excellent protein sources in daily ration of calves. In this study, the starter DMI of the WP and PP groups were similar to that of the MP group, but the ADG of the WP and PP groups, 626.7 and 554.2 g/d, respectively, were significant lower than 775.6 g/d of the MP group (P < 0.05), which was opposite to the conclusion of Ortigues-Marty et al. (2003) that feeding wheat protein milk replacers to calves gained a growth performance similar to that of feeding calves full MP milk replacers. However in Ortigues-Marty's study, wheat protein accounted for 49% TP, which was lower than 70% of this experiment. This indicates that at the nutrient level of the present study, wheat protein or peanut protein, which accounted for 70% TP, had detrimental effects on growth performance of suckling calves. The SP and RP selected in this experiment were likely to better satisfy the digestibility and nutritional needs of suckling calves using the same level of main essential amino acids and nutrient in the milk replacers, whereas WP and PP reduced the protein digestibility and production performance of calves due to anti-nutritional factors etc.

4.2. Effects of protein sources for milk replacers on body sizes of suckling calves

Animal growth is a coordinated and developmental process in terms of various aspects. The condition and appearance of an animal body directly reflect the condition of body growth (Zhang et al., 2010). A close relationship exists between BW and body size (Heinrichs et al., 1992). The most significant relationship was between chest circumference and BW (Davis et al., 1961). The body size of calves that fed full MP was regarded as normal growth and development in this study. The body size of calves significantly increased with age in each group, and no significant difference was shown between the VP groups and the MP group which indicates that MP and VP that were selected in this experiment had similar functions in ensuring physical growth.

The withers height, body length and chest circumference of an animal could accurately reflect the growth and development levels of bones (Wickersham and Schultz, 1963). The present experiment showed that these indexes were higher of the MP, SP, RP groups than of the WP and PP groups, and DMI showed no significant differences among groups from 21 to 56 days, because the calves at this age had very limited abilities to digest nutrition of the starter due to underdeveloped rumen, thus they mainly depend on liquid feed before weaning. Compared with the other 3 groups, the WP and PP groups likely had lower protein digestion levels, thus the digestible nutrients of the 2 groups may be insufficient, which might cause a difference in the growth of bones, but the difference was not significant in statistics.

4.3. Effects of protein sources for milk replacers on serum biochemical indexes of suckling calves

The concentration of BUN in blood sera can accurately reflect the conditions of protein metabolism and dietary amino acid balance in animal bodies (Stanley et al., 2002). In this experiment, 4 protein sources for milk replacers had no significant effects on the BUN concentration but the BUN concentration of all VP groups was lower than that of the MP group, and the lowest BUN concentration was in the WP and PP groups. This result indicated that the digestibility is lower of VP than of MP, and different VP have different digestibilities. The low digestibility of protein means a low level of digestible protein in the daily ration, which was supported by the report of Li et al. (2008) that the BUN concentration in blood sera of calves was lower for low protein level daily rations than for high protein level daily rations. Therefore, milk replacers should contain a higher level of crude protein in VP milk replacers than in full MP (Sanz et al., 1997).

Inadequate nutrient intake or stress would cause the TP concentration in the blood sera of calves to decline (Sampelayo et al., 1997). Effects of protein sources on TP, ALB, ALOB concentrations, and albumin:globulin ratio (A:G) in blood sera of calves were not significant in this experiment. Calves in the MP group had higher ALB concentrations and A:G than those in the other 4 groups. The WP and PP groups had lowest values of ALB, TP concentrations in blood sera and A:G among the 4 VP groups. This is an indication that calves in the WP and PP groups were likely to have higher immune activation reactions than the other 3 groups, and accordingly the proportions of nutrient intakes in order to ensure growth were lower in the WP and PP groups than in the other 3 groups (Jianhong et al., 2012). This conclusion was in line with the poor growth performance of the WP and PP groups in this experiment.

When the metabolism of glucose and lipid was abnormal in an animal body, it would cause the concentration of β-HB to rise in the serum (Gilbert et al., 2000). The concentrations of β-HB had no significant differences among groups, and basically maintained between 50 and 61 mmol/L, thus the effects of protein sources on calf glucose and lipid metabolism could be ignored.

4.4. Effects of protein sources for milk replacers on hormone indexes of suckling calves

Growth hormone can promote amino acids in muscle tissues to move into cells and enhance the synthesis of protein (Breier, 1999). The effects of protein sources on the concentration of GH in sera were not significant in this experiment. The GH concentrations of the MP, SP, and RP groups continuously increased with age, however, they firstly declined and then rose to normal levels with age in the WP, PP groups during the whole experiment period. The result indicated that protein sources had a little effect on relevant protein anabolism but the effect didn't reach study significance. Adding soybean or rice protein to milk replacers up to 70% TP could achieve a similar level of protein anabolism as of using full MP. Adding wheat or peanut protein to milk replacer up to 70% TP likely had detrimental effects on protein anabolism of calves. However, calves enhanced the utilization ability of wheat and peanut protein with age and the functions of protein anabolism gradually restored to the level of the MP group.

Insulin-like growth factor-1 was a peptide mainly secreted by the liver cells and bone marrow cells and played an important role in protein retention, and it could reduce protein oxidation and enhance protein synthesis in body tissues, and the secretion of IGF-1 was controlled by GH (Brameld et al., 1996). Kita et al. (2000) verified that the concentration of IGF-1 in the serum partly affected the velocity of muscle protein syntheses. Studies also have shown that the nutrient level, protein quality and source of daily ration would affect the level of IGF-1 gene expression, thereby control body protein metabolism (Pell et al., 1993, Pell and Bates, 1987, Bartke, 1999). Therefore the IGF-1 concentration in the serum likely reflected the change of body protein metabolism and nitrogen balances. The effects of protein sources on the IGF-1 concentrations of calves were not significant in this experiment. During the whole experiment period, the IGF-1 concentration did not show big fluctuations among all groups although it was higher in the MP group than in the other 4 groups with the lowest in the WP, PP groups. The present study controlled essential amino acids in milk replacers to a same nutrient level by adding crystalline amino acids, this probably improved the quality and digestibility of VP. However, it is not satisfactory for weight gains in the WP and PP groups. This indicated that different protein sources gave rise to the different growth and development of calves. This warrants further studies. As the IGF-1 concentration in sera of this experiment showed, it was entirely feasible to use VP as main proteins for milk replacers under the current condition of nutrition regulation.

5. Conclusions

Basing on the nutrition level of this experiment, we draw the following conclusions:

-

1)

Under basically the same condition of nutrient levels (including the 4 types of essential amino acids), SP and RP as main protein sources for milk replacers have similar effects on weight gain performance and feed conversion ratio of suckling calves as full MP, but WP and PP have worse effects. Different VP as main protein sources for milk replacers have different effects on the growth performance of sucking calves.

-

2)

The effects of different protein sources for milk replacers on metabolite in calf sera are not significant (no stress beyond the affordable range of calf body appeared).

In summary, high-quality VP can be used as main protein sources for milk replacers by using the nutritional manipulation technique of this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank laboratory staff at the Institute of feed research of the CAAS for their assistance during the implementation of the experiment and the analysis of experimental samples. The authors also thank farm staff at Zhuochen livestock Co. Ltd., Beijing for their assistance during feeding experiment.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

References

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists . 13th ed. AOAC; Washington, DC: 1980. Official methods of analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Bartke A. Role of growth hormone and prolactin in the control of reproduction: what are we learning from transgenic and knock-out animals. Steroids. 1999;64(9):598–604. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(99)00039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breier B.H. Regulation of protein and energy metabolism by the somatotropic axis. Dome Anim Endocrin. 1999;17:209–218. doi: 10.1016/s0739-7240(99)00038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brameld J.M., Atkinson J.L., Saunders J.C., Pell J.M., Buttery P.J., Gilmour R.S. Effects of growth hormone administration and dietary protein intake on insulin-like growth factor I and growth hormone receptor mRNA expression in porcine liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue. J Anim Sci. 1996;74(8):1832–1841. doi: 10.2527/1996.7481832x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis H.P., Swett W.W., Harvey W.R. Relation of heart girth to weight in Holsteins and Jerseys. Nebraska Agric Exp Station Res Bull. 1961;194 [Google Scholar]

- Drackley C.L., Davis . 1st ed. Iowa State University Press; Ames: 1998. The development, nutrition, and management of the young calf; p. 339. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson P.S., Schauff D.J., Murphy M.R. Diet digestibility and growth of Holstein calves fed acidified milk replacers containing soy protein concentrate. J Dairy Sci. 1989;72(6):1528–1533. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(89)79263-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert D.L., Pyzik P.L., Freeman J.M. The ketogenic diet: seizure control correlates better with serum β-hydroxybutyrate than with urine ketones. J Child Neurol. 2000;15(12):787–790. doi: 10.1177/088307380001501203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs A.J. Raising dairy replacements to meet the needs of the 21st century. J Dairy Sci. 1993;76(10):3179–3187. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(93)77656-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs A.J., Rogers G.W., Cooper J.B. Predicting BW and wither height in Holstein heifers using body measurements. J Dairy Sci. 1992;75(12):3576–3581. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(92)78134-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill T.M., Bateman H.G., Aldrich J.M. Effects of using wheat gluten and rice protein concentrate in dairy calf milk replacers. Pro Anim Sci. 2008;24(5):465–472. [Google Scholar]

- Jianhong W., Qiyu D., Yan T., Naifeng Z., Xiancha X. The limiting sequence and proper ratio of lysine, methionine and threonine for calves fed milk replacers containing soy protein. Asian Austr. J Anim Sci. 2012;25(2):224–233. doi: 10.5713/ajas.2011.11190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita K., Noda C., Miki K., Kino K., Okumura J. Relationship of IGF-I mRNA levels to tissue development in chicken embryos of different strains. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci. 2000;13(12):1653–1658. [Google Scholar]

- Lalles J.P., Toullec R., Pardal P.B. Hydrolyzed soy protein isolate sustains high nutritional performance in veal calves. J Dairy Sci. 1995;78(1):194–204. doi: 10.3168/jds.s0022-0302(95)76629-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesmeister K.E., Heinrichs A.J. Effects of corn processing on growth characteristics, rumen development, and rumen parameters in neonatal dairy calves. J Dairy Sci. 2004;87(10):3439–3450. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(04)73479-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Diao Q.Y., Zhang N.F., Fan Z.Y. Growth, nutrient utilization and amino acid digestibility of dairy calves fed milk replacers containing different amounts of protein in the preruminant period. Asian-Austr J Anim Sci. 2008;21(8):1151–1158. [Google Scholar]

- Ortigues-Marty I., Hocquette J.F., Bertrand G., Martineau C., Vermorel M., Toulle R. The incorporation of solubilized wheat proteins in milk replacers for veal calves: effects on growth performance and muscle oxidative capacity. Reprod Nutr Devel. 2003;43(1):57–76. doi: 10.1051/rnd:2003006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pell J.M., Bates P.C. Collagen and non-collagen protein turnover in skeletal muscle of growth hormone-treated lambs. J Endocrin. 1987;115(1):R1–R4. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.115r001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pell J.M., Saunders J.C., Gilmour R.S. Differential regulation of transcription initiation from insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) leader exons and of tissue IGF-I expression in response to changed growth hormone and nutritional status in sheep. Endocrinology. 1993;132(4):1797–1807. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.4.8462477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz Sampelayo M.R., Ruiz Mariscal I., Gil Extremera F., Boza J. The effect of different concentrations of protein and fat in milk replacers on protein utilization in kid goats. Anim Sci. 1997;64(3):485–492. [Google Scholar]

- Smith R.H., Sissons J.W. The effect of different feeds, including those containing soya-bean products, on the passage of digesta from the abomasum of the preruminant calf. Brit J Nutr. 1975;33(03):329–349. doi: 10.1079/bjn19750039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley C., Williams C., Jenny B. Effects of feeding milk replacer once versus twice daily on glucose metabolism in Holstein and Jersey calves. J Dairy Sci. 2002;85(9):2335–2343. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(02)74313-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomkins T., Sowinske J., Drackley J.K. Milk replacer research leads to new developments. Feedstuffs. 1994;66(42):13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Tomkins T., Sowinski J., Drackley J.K. Proc. 55th Minnesota Nutr. Conf. 1994. New developments in milk replacers for pre-ruminants; pp. 71–89. [Google Scholar]

- Wickersham E.W., Schultz L.H. Influence of age at first breeding on growth, reproduction, and production of well-fed Holstein Heifers 1, 2. J Dairy Sci. 1963;46(6):544–549. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R., Diao Q.Y., Tu y, Zhang N.F. Effects of different energy levels on nutrient utilization and serum biochemical parameters of early-weaned calves. Agric Sci Chin. 2010;9(5):729–735. [Google Scholar]