Abstract

This study was to determine the fermentation quality of a mixture of corn steep liquor (CSL) (178 g/kg wet basis) and air-dried rice straw (356 g/kg wet basis) after being treated with inoculants of different types of lactic acid bacteria (LAB). The treatments included the addition of no LAB additive (control), which was deionized water; homo-fermentative LAB alone (hoLAB), which was Lactobacillus plantarum alone), and a mixture of homo-fermentative and hetero-fermentative LAB (he + hoLAB), which were L. plantarum, Lactobacillus casei, and Lactobacillus buchneri. The results showed that the inoculation of the mixture of CSL and air-dried rice straw with he + hoLAB significantly increased the concentration of acetic acid and lactic acid compared with the control (P < 0.05). The addition of he + hoLAB effectively inhibited the growth of yeast in the silage. The concentration of total lactic acid bacteria in the he + hoLAB-treated silage was significant higher than those obtained in other groups (P < 0.05). The duration of the aerobic stability of the silages increased from 56 h to >372 h. The control group was the first to spoil, whereas the silage treated with he + hoLAB remained stable throughout the 372 h period of monitoring. The results demonstrated that the he + hoLAB could effectively improve the fermentation quality and aerobic stability of the silage.

Keywords: Air-dried rice straw, Aerobic stability, Corn steep liquor, Lactic acid bacteria, Silage

1. Introduction

China is an agricultural country with abundant straw resources (Bi et al., 2008). However, only 15% of the rice straw is fed to ruminants; the rest is burnt or buried in the field (Wang et al., 2011). Under natural conditions, fresh rice straws rapidly become air-dried. Thus, it is not a suitable feed for animals because of its low digestibility, poor palatability, high crude fibre, and low protein content. Corn steep liquor (CSL) is a major by-product obtained from the wet-milling industry. It contains a rich complement of organic nitrogen and vitamins, which is capable of replacing yeast extract in a variety of fermentation process (Nascimento et al., 2009). Corn steep liquor has been successfully used in the production of enzymes (Silveira et al., 2001), lactic acid (Agarwal et al., 2006, Liu et al., 2010), and ethanol (Silveira et al., 2001, Saxena and Tanner, 2012). Consequently, air-dried rice straw, as an extensive source of absorbers, can be mixed and ensilaged with CSL effectively. However, the stems of air-dried rice straw have weak natural adhesion to lactic acid bacteria (LAB), thus it is essential to add silage bacterial additives to the mixture of CSL and rice straw to improve the concentration of LAB (Wilkinson, 2005).

Commercial homo-fermentative LAB (hoLAB) inoculants have been developed to ensure rapid and efficient fermentation of water-soluble carbohydrate (WSC) into lactic acid, a rapid decrease in pH, and improved silage conservation with minimal fermentation losses (Huisden et al., 2009, Weinberg et al., 1993). However, such inoculants have also been responsible for decreasing the aerobic stability of silages observed in many studies (Weinberg et al., 1993, Kleinschmit et al., 2005) because antifungal volatile fatty acid (VFA) are lowered and lactic acid is easily oxidized by aerobic microorganisms (MacDonald et al., 1991, Kleinschmit et al., 2005). The aerobic stability of forage with Lactobacillus buchneri inoculation can be considerably enhanced by the metabolic activity of converting lactic acid to acetic acid under anaerobic conditions, and the silage could remain cool; thus, it does not spoil as long as 30 d when it is exposed to air (Driehuis et al., 1999, Elferink et al., 2001). Recently, dual-purpose inoculants containing homo-fermentative and hetero-fermentative bacteria have been developed to overcome the limitations of inoculants containing either type of bacteria alone, and the combination of both types of organisms has the potential to improve the speed of fermentation and enhance the aerobic stability (Nishino et al., 2007, Reich and Kung, 2010, Schmidt and Kung, 2010, Conaghan et al., 2010, Kung et al., 2003), but the fermentation of a mixture of CSL and air-dried rice straw with LAB inoculants (Lactobacillus plantarum, L. buchneri and Lactobacillus casei) has not yet been studied.

The present work was to study the effects of ensiling a mixture of CSL and air-dried rice straw with hoLAB alone or in combination with hetero-fermentative LAB (he + hoLAB) on the fermentation quality and aerobic stability. This experiment was performed by the application of the microorganisms to laboratory silages. The ability to successfully convert a mixture of CSL and air-dried rice straw into a new type of ruminant fermentation feed will promote the improvement in the ecological environment and the cyclic development of the agricultural economy.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Forage and ensiling

2.1.1. Experimental materials

Rice straws were collected from the Xiangfang Experimental Farm of Northeast Agricultural University (Harbin, China), air-dried to 10% dry matter (DM), and chopped to a theoretical length of 2 to 3 cm. Corn steep liquor obtained from the Cargill Biochemistry Co., Ltd. (Songyuan, China) was used in the study.

2.1.2. Treatments

The CSL (178 g/kg, wet basis) were mixed with 356 g/kg air-dried rice straw (wet basis) thoroughly before the application of the different fermentation inoculants. The mixture was then assigned to one of the following treatments: 1) deionized water, untreated (control); 2) L. plantarum, alone (hoLAB); 3) L. plantarum, L. casei, and L. buchneri, a mixture of homo- and hetero-fermentative LAB (he + hoLAB). The application rate of each inoculant to the fresh forage was 1 × 106 cfu/g of fresh matter (FM). The L. plantarum strain isolated from a commercial inoculant (Silage. help) was used. The he + hoLAB obtained from Northeast Agricultural University consisted of 2 strains of hoLAB (L. plantarum and L. casei) in combination with a heLAB (L. buchneri). In this experiment, the bacterial additive of each group was inoculated in De Man, Rogosa, or Sharpe (MRS) broth for 48 h, and the bacteria were then plated on MRS agar overnight to confirm their viability. Appropriate amounts of the inoculants were then used to achieve the desired application rate. The inoculants were applied at a rate of 50 mL/kg (wet basis) forage with a sprayer. Approximately 416 mL/kg (wet basis) deionized water was sprayed onto the mixture to achieve a final moisture content of 60%. To ensure that the amount of moisture was equal to what was found in the microbial-treated group, the control silage was sprayed with 466 mL/kg (wet basis) deionized water. Approximately 300 g (wet basis) of forage from each treatment were packed into a plastic bag (polyethylene; 400 mm × 500 mm), and all of the bags were sealed with a vacuum sealer and stored indoors for 60 days at ambient temperature (18 ± 2 °C). Duplicate silos for each treatment were opened after 0, 3, 5, 7, 10, 30, 45 and 60 days. The silages were randomly subsampled from several different positions, and then mixed to generate a composite sample for microbiological and chemical analysis. The rest of the bag was subjected to an aerobic stability test after 60 days.

2.2. Chemical and microbial analysis

The silage samples were dried at 65 °C and analysed for DM according to AOAC (1990) procedures. The nitrogen (N) content was measured using the Kjeldahl method (AOAC, 1990). The CP was calculated as N × 6.25. The acid detergent fibre (ADF) and neutral detergent fibre (NDF) values were analysed according to the procedures described by Van Soest et al. (1991) using the Ankom system (Ankom 220 fibre analyser; Ankom) with heat-stable α-amylase. The WSC concentration was measured through the colorimetric method (Dubois et al., 1956). Both fresh and silage juice were extracted by blending 10 g forage (wet basis) in 90 mL of distilled water and storing the mixture for 24 h at 4 °C in a refrigerator (Nishino and Uchida, 1999). The slurry mixture was then filtered through 4 layers of cheesecloth (Xing et al., 2009), and the filtrate was used for pH, ammonia-N, lactic acid and VFA determination. The pH was directly measured using a pH meter (Sartorius Basic pH Meter, Germany). The ammonia-N (NH3—N) concentration was determined using an ammonia-sensing electrode (Expandable Ion Analyser EA 940, Orion, USA). Samples for VFA analysis were prepared as described by Li and Meng (2006). The concentrations of VFA were analysed using a gas–liquid chromatography (GC, 2010, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a flame-ionization detector and a free fatty acid phase (FFAP) capillary column (HP-INNOWAX, 30 m × 0.250 mm × 0.25 μm). The lactic acid content was determined using a high-performance liquid chromatography (Waters 600, Tokyo, Japan) following the procedure described by Muck and Dickerson (1987).

Another portion of the fresh silage juices was extracted by blending 10 g forages (wet basis) in 90 mL distilled water for 30 min at ambient temperature, and then filtered through a double layer of cheesecloth. The filtrate was divided into 2 sets of LAB by pour-plating on MRS agar, and the yeasts and moulds were enumerated by pouring the filtrate onto malt extract agar (Oxoid CM0059). The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h, and then numbers of colony-forming units were counted.

All of the chemical analyses were conducted in triplicates, and the results were expressed on a DM basis except that the microbiological data were transformed to log units (% fresh matter), DM content (% fresh matter) and NH3—N (% total nitrogen).

2.3. Statistical analysis

The data were analysed as a completely randomized design using the ANOVA procedure of SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, 1999). The results were presented as the mean values and standard error of the means. Differences between treatment means were determined by Duncan's multiple range test method.

3. Results

The chemical compositions of CSL, air-dried rice straw, and their mixture before ensiling are showed in Table 1. The dry matter content of each treatment was adjusted to 40%. The content of CSL (characterized by high protein content) was up to 37% DM, which was favourable for the growth of bacteria. As shown in Table 1, the application of CSL effectively increased the protein content of the dry rice straw to 9.95%. The content of NDF and ADF of dry rice straw decreased to 54.82% and 34.12%, respectively. The concentration of WSC in the mixture of CSL and rice straw pre-ensiling was 3.25% DM.

Table 1.

Chemical composition (%) of raw materials before ensiling (DM basis).

| Item | Treatment |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| CSL | Rice straw | CSL + rice straw1 | |

| DM | 45.62 | 89.19 | 40.00 |

| CP | 37.00 | 3.23 | 9.95 |

| NDF | 0.04 | 69.09 | 54.82 |

| ADF | 0.06 | 43.18 | 34.12 |

| Ash | 15.57 | 14.8 | 15.41 |

| WSC | 6.95 | 2.9 | 3.25 |

CSL = corn steep liquor; NDF = neutral detergent fibre; ADF = acid detergent fibre; WSC = water-soluble carbohydrate.

The mixture of approximately 416 mL/kg (wet basis) deionized water, 356 g/kg air-dried rice straw (wet basis) and 178 g/kg CSL (wet basis).

The populations of the LAB and yeast in the mixture of CSL and air-dried rice straw silages after 0-d, 3-d, 5-d, 7-d, 10-d, 30-d, 45-d and 60-d ensiling are showed in Table 2. After 5-d ensiling, the population of LAB in he + hoLAB-treated silage increased rapidly from 7.72 log10cfu/g to 9.30 log10cfu/g of FM, which was significantly higher than those of the other two treatments (P < 0.05). In contrast, the populations of LAB in control and hoLAB-treated silage began to decrease after 5 d. After 60-d ensiling, the count of total LAB in he + hoLAB-treated silage was significant higher than those in control and hoLAB-treated silage (P < 0.05). All of the 3 treatments showed that the yeast population had a decreasing trend after 5-d ensiling (Table 2). Compared with the control and hoLAB-treated silage, he + hoLAB-treated silage had a significant lower count of yeast existed in during 60-d ensiling (P < 0.05). In addition, no mould was found during the 60-d ensiling in all of the samples.

Table 2.

Changes of the population of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and yeast in corn steep liquor (CSL) and air-dried rice straw silages during 60 days of ensiling (log10cfu/g) 1.

| Item | Treatments |

SEM | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control2 | hoLAB3 | he + hoLAB4 | |||

| Population of LAB, log10cfu/g | |||||

| 0 d | 6.83b | 7.73a | 7.72a | 0.19 | <0.05 |

| 3 d | 7.45c | 7.88b | 9.02a | 0.30 | <0.05 |

| 5 d | 7.75c | 8.00b | 9.30a | 0.30 | <0.05 |

| 7 d | 7.58b | 7.69b | 9.06a | 0.30 | <0.05 |

| 10 d | 7.28b | 7.47b | 9.10a | 0.37 | <0.05 |

| 30 d | 6.73c | 7.04b | 8.82a | 0.41 | <0.05 |

| 45 d | 6.34b | 6.47b | 8.98a | 0.54 | <0.05 |

| 60 d | 6.04c | 6.35b | 8.75a | 0.54 | <0.05 |

| Population of yeast, log10cfu/g | |||||

| 0 d | 6.92 | 6.94 | 6.95 | 0.01 | NS |

| 3 d | 7.85b | 7.97a | 7.49c | 0.09 | <0.05 |

| 5 d | 7.76a | 7.93a | 7.46c | 0.09 | <0.05 |

| 7 d | 7.45a | 7.30b | 6.92c | 0.10 | <0.05 |

| 10 d | 7.32a | 7.03b | 5.95c | 0.26 | <0.05 |

| 30 d | 6.69a | 5.95b | 2.15c | 0.89 | <0.05 |

| 45 d | 6.15a | 5.14b | 0.00c | 1.21 | <0.05 |

| 60 d | 6.02a | 5.02b | 0.00c | 1.18 | <0.05 |

SEM = standard error of the mean; NS = not significant.

a, b, c Within a same row, means with different letters differ (P < 0.05).

Values are presented as the mean values (n = 3).

Control means no additive applied.

hoLAB means homo-fermentative LAB alone (L. plantarum).

he + hoLAB means a mixture of hoLAB and hetero-fermentative LAB (L. plantarum, L. casei, L. buchneri).

The chemical compositions and fermentation characteristics of a mixture of CSL and air-dried rice straw silages after 60 d of ensiling are showed in Table 3. The silage CP ranged from 10.26% to 10.39% and there was no significant difference between groups. Inoculation with he + hoLAB had no effects on the ADF content of silages compared with inoculation with hoLAB or control silages; however, it had a higher concentration of NDF than the other 2 groups (P < 0.05). The residual WSC was significantly lower (P < 0.05) in the he + hoLAB-treated silage compared with the amount in the hoLAB-inoculated or control silages. In addition, he + hoLAB had a higher concentration of WSCL than the other two groups (P < 0.05). Moderately higher pH value of the he + hoLAB-treated silage was detected compared with the pH values of the control and hoLAB-treated silage (P < 0.05). After 60 days of ensiling, the silage inoculated with he + hoLAB had a higher content of NH3—N (fresh matter) compared with the hoLAB-treated and control silages (P < 0.05). As shown in Table 3, the silage inoculated with he + hoLAB resulted in a higher ratio of NH3—N to total nitrogen compared with the control and hoLAB-treated silage (P < 0.05). The highest level of acetic acid was observed in the he + hoLAB-treated silage (2.31%), and this level was significantly higher in this treatment than in hoLAB-treated or control (P < 0.05). The control group had the lowest (P < 0.05) concentration of lactic acid (4.02% DM) compared with the hoLAB (5.11% DM) and he + hoLAB-treated silages (5.62% DM). As shown in Table 3, the ratios of lactic acid to acetic acid for the control and hoLAB-treated silages were 3.56 and 3.60, respectively. In contrast, the ratio for he + hoLAB-treated silage was 2.43. No butyric acid was detected in this experiment.

Table 3.

Chemical compositions and fermentation characteristics of corn steep liquor (CSL) and air-dried rice straw silages after 60 days of ensiling 1.

| Item | Treatments |

SEM | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control2 | hoLAB3 | he + hoLAB4 | |||

| Chemical compositions | |||||

| DM, % | 39.28c | 39.71b | 39.98a | 0.13 | <0.05 |

| CP, % DM | 10.26 | 10.32 | 10.39 | 0.04 | NS |

| NDF, % DM | 59.38b | 60.62a | 61.24a | 0.31 | <0.05 |

| ADF, % DM | 37.7 | 37.82 | 37.09 | 0.24 | NS |

| WSC, % DM | 0.63a | 0.57a | 0.46b | 0.03 | <0.05 |

| WSCL, % | 80.74b | 82.39b | 85.82a | 0.78 | <0.05 |

| Fermentation characteristics | |||||

| pH | 4.45b | 4.43b | 4.52a | 0.02 | <0.05 |

| NH3–N | 0.07c | 0.13b | 0.16a | 0.02 | <0.05 |

| NH3–N, % of total N | 4.40c | 7.83b | 9.81a | 1.01 | <0.05 |

| AA, % DM | 1.13c | 1.42b | 2.31a | 0.23 | <0.05 |

| LA, % DM | 4.02b | 5.11a | 5.62a | 0.31 | <0.05 |

| LA:AA, % DM | 3.56a | 3.60a | 2.43b | 0.25 | <0.05 |

SEM = standard error of the mean; NS = not significant; NDF = neutral detergent fibre; ADF = acid detergent fibre; WSC = water-soluble carbohydrate; WSCL = WSC loss; LA = Lactic acid; AA = acetic acid.

a, b, c Within a same row, means with different letters differ (P < 0.05).

Values are presented as mean values (n = 3).

Control means no additive applied.

hoLAB means homo-fermentative LAB alone (L. plantarum).

he + hoLAB means a mixture of homo-fermentative LAB and hetero-fermentative LAB (L. plantarum, L. casei, L. buchneri).

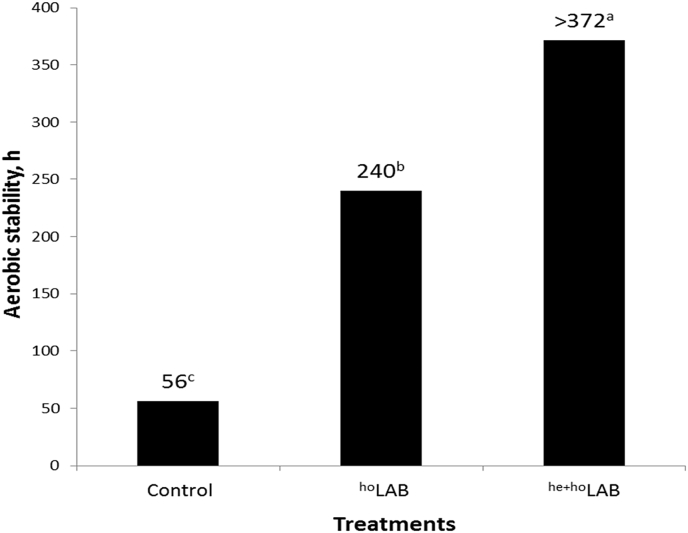

The aerobic stability of the silage is presented in Fig. 1. The aerobic stability of the silages ranged from 56 h to >372 h. The control group was the first to spoil, whereas the silage treated with he + hoLAB remained stable throughout the 372-h period of monitoring.

Fig. 1.

Effects of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) inoculants on the aerobic stability (hours for the feed temperature to increase 2 °C above ambient temperature) of silages, a mixture of corn steep liquor (CSL) and air-dried rice straw silages, after 60 days of ensiling. Treatments: Control means no LAB additive; hoLAB means homo-fermentative lactic acid bacteria alone (Lactobacillus plantarum); he + hoLAB means a mixture of hoLAB and hetero-fermentative LAB (Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus buchneri). a, b, c Above a bar, means with different superscripts differ (P < 0.05).

4. Discussion

The growth of LAB via fermentation requires adequate WSC supplement (MacDonald et al., 1991), and low levels may restrict fermentation process of it. The initial concentration of WSC is sufficient to ensure adequate ensiling (Haigh and Parker, 1985). Hetero-fermentative bacteria L. buchneri could generate energy by fermenting sugars, which results in the increase of their numbers during the initial phase of fermentation (Schmidt et al., 2009). The addition of CSL for the air-dried rice straw silage increases the available N source for LAB growth; however, high viscosity and some inhibitory component in CSL could also inhibit the growth of it (Agarwal et al., 2006). The addition of hoLAB in silages did not effectively promote the fermentation process. The decrease in yeast over time was partly due to the growth of LAB, especially, L. buchneri in he + hoLAB-treated silages. Driehuis et al. (1999) reported that L. buchneri could inhibit the growth of yeast by the production of acetic acid both during ensiling and after exposure to air.

The content of CP was unaffected by treatments with different fermentation types of microbial inoculants. This finding was in agreement with the addition of L. buchneri to barley silage (Kung and Ranjit, 2001). Hetero-fermentative bacteria of L. buchneri in he + hoLAB consumes more nutrients during fermentation than homo-fermentative bacteria (Guo et al., 2013), which results in greater NDF concentration on a DM basis in the he + hoLAB-treated silage. Moreover, the inoculation of the silages with L. buchneri could result in a lower concentration of WSC in the silage (Kung and Ranjit, 2001). The significantly low residual WSC in the he + hoLAB-treated silage indicates that WSC is better utilized by the fermentation bacteria in he + hoLAB.

The higher pH value of he + hoLAB-treated silage was partly due to the production of acetic acid from lactic acid by L. buchneri (Elferink et al., 2001). Kleinschmit and Kung Jr (2006) reported that the addition of L. buchneri to silages always resulted in a higher pH value. It was proposed that the higher concentration of NH3—N, as a result of inoculation with L. buchneri, may contribute to the increase of pH as a result of he + hoLAB addition (Driehuis et al., 2001). Although the addition of classical homo-fermentative acid bacteria to silage often resulted in a decrease in NH3—N (Muck and Kung, 1997, Conaghan et al., 2010), the addition of the homo-fermentative bacteria L. plantarum in he + hoLAB could not prevent the increase induced by hetero-fermentative bacteria L. buchneri. Some other studies also reported that addition of L. buchneri increased the NH3—N content in alfalfa (Kung et al., 2003, Schmidt et al., 2009) and grass silage (Driehuis et al., 2001). The NH3—N concentrations of total nitrogen in all of the experimental groups were less than 10%, which demonstrated that the N in silages were well-preserved (McDonald et al., 2002). Acetic acid has been reported as a potent inhibitor of fungi, and plays an active role in aerobic deterioration (MacDonald et al., 1991). Driehuis et al. (1999) and Elferink et al. (2001) reported that L. buchneri can produce acetic acid from a novel fermentation of lactic acid under anaerobic conditions. The lactic acid contents of all groups were higher than that (2%) estimated for good-quality silages (Kīlīc, 1986). This higher concentration of lactic acid in hoLAB and he + hoLAB can be explained by the addition of the hoLAB, which could ensure rapid and vigorous fermentation by promoting the production of lactic acid (Muck and Kung Jr, 1997). Kung and Stokes (2001) reported that the ratio of a lactic acid to acetic acid, that was more than 3:1, was an indication of a homolactic dominant fermentation. As shown in Table 2, both ratios of the control and hoLAB-treated silage were more than 3:1. This result suggests that the fermentation with he + hoLAB is dominated by hetero-fermentative bacteria L. buchneri, which can also well explain the high NH3—N, pH and acetic acid in the he + hoLAB-treated silage.

It has been reported that residual WSC content, the concentration of lactic acid and antifungal VFA in silages are associated with aerobic spoilage (Weinberg et al., 1993). The residual WSC in the control was higher than those in other groups, and the concentration of acetic acid in the control was the lowest. Thus, the duration of its aerobic stability was short. Silage treated with hoLAB showed lower stability, and heating appeared earlier in this group than in the he + hoLAB-treated silage. This production of acetic acid by L. buchneri considerably enhanced the aerobic stability of he + hoLAB, and the silage could remain unheated for over 372 h. In some studies, corn silage treated with L. buchneri did not spoil throughout 792-h (Driehuis et al., 1999) and 900-h (Ranjit and Kung Jr, 2000) aerobic exposure.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that the treatment of a mixture of CSL and air-dried rice straw with an inoculant containing a blend of hoLAB and heLAB may be a promising means of improving the fermentation quality and aerobic stability of silages.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Dairy Industry and Technology System project (CARS-37) of Agriculture Ministry in China.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

References

- Agarwal L., Isar J., Meghwanshi G.K., Saxena R.K. A cost effective fermentative production of succinic acid from cane molasses and corn steep liquor by Escherichia coli. J Appl Microbiol. 2006;100:1348–1354. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.02894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC . 15th ed. Association of official Analytical Chemists; Arlington: 1990. Official methods of analysis of AOAC international. [Google Scholar]

- Bi Y., Wang D., Gao C., Wang Y. Chinese Agricultural Science and Technology Publishing House; Beijing, PRC: 2008. Straw resources evaluation and utilization in China; pp. 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Conaghan P., O'Kiely P., O'Mara F. Conservation characteristics of wilted perennial ryegrass silage made using biological or chemical additives. J Dairy Sci. 2010;93:628–643. doi: 10.3168/jds.2008-1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driehuis F., Elferink S., Spoelstra S. Anaerobic lactic acid degradation during ensilage of whole crop maize inoculated with Lactobacillus buchneri inhibits yeast growth and improves aerobic stability. J Appl Microbiol. 1999;87:583–594. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driehuis F., Oude Elferink S., Van Wikselaar P. Fermentation characteristics and aerobic stability of grass silage inoculated with Lactobacillus buchneri, with or without homofermentative lactic acid bacteria. Grass Forage Sci. 2001;56:330–343. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois M., Gilles K.A., Hamilton J.K., Rebers P t, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem. 1956;28:350–356. [Google Scholar]

- Elferink S.J.O. Anaerobic conversion of lactic acid to acetic acid and 1, 2-propanediol by Lactobacillus buchneri. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:125–132. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.1.125-132.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigh P., Parker J. Effect of silage additives and wilting on silage fermentation, digestibility and intake, and on liveweight change of young cattle. Grass Forage Sci. 1985;40:429–436. [Google Scholar]

- Huisden C., Adesogan A., Kim S., Ososanya T. Effect of applying molasses or inoculants containing homofermentative or heterofermentative bacteria at two rates on the fermentation and aerobic stability of corn silage. J Dairy Sci. 2009;92:690–697. doi: 10.3168/jds.2008-1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinschmit D., Kung L., Jr. A meta-analysis of the effects of Lactobacillus buchneri on the fermentation and aerobic stability of corn and grass and small-grain silages. J Dairy Sci. 2006;89:4005–4013. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(06)72444-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinschmit D., Schmidt R., Kung L., Jr. The effects of various antifungal additives on the fermentation and aerobic stability of corn silage. J Dairy Sci. 2005;88:2130–2139. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(05)72889-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung L., Jr., Stokes M.R. Analyzing silages for fermentation end products. Univ Del Coll Agric Nat Resour. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Kung L., Jr., Taylor C., Lynch M., Neylon J. The effect of treating alfalfa with Lactobacillus buchneri 40788 on silage fermentation, aerobic stability, and nutritive value for lactating Dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 2003;86(1) doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(03)73611-X. 336–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung L., Ranjit N.K. The effect of Lactobacillus buchneri and other additives on the fermentation and aerobic stability of barley Silage1. J Dairy Sci. 2001;84:1149–1155. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(01)74575-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Meng Q. Effect of different types of fibre supplemented with sunflower oil on ruminal fermentation and production of conjugated linoleic acids in vitro. Arch Anim Nutr. 2006;60(5):402–411. doi: 10.1080/17450390600884401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Yang M., Qi B., Chen X., Su Z., Wan Y. Optimizing l-(+)-lactic acid production by thermophile Lactobacillus plantarum As.1.3 using alternative nitrogen sources with response surface method. Biochem Eng J. 2010;52:212–219. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald P., Henderson A., Heron S. Chalcome publications; Great Britain: 1991. The Biochemistry of silage. Chapter 2: crops for silage. [Google Scholar]

- Muck R., Dickerson J. Storage temperature effects on proteolysis in alfalfa silage. Am Soc Agric Eng. 1987 [Google Scholar]

- Muck R., Kung L., Jr. Effects of silage additives on ensiling. Silage Field Feed. 1997 NRAES-99. [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento R.P., Junior N.A., Pereira N., Jr., Bon E.P.S., Coelho R.R.R. Brewer's spent grain and corn steep liquor as substrates for cellulolytic enzymes production by Streptomyces malaysiensis. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2009;48:529–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2009.02575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino N., Hattori H., Wada H., Touno E. Biogenic amine production in grass, maize and total mixed ration silages inoculated with Lactobacillus casei or Lactobacillus buchneri. J Appl Microbiol. 2007;103:325–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.03244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino N., Uchida S. Laboratory evaluation of previously fermented juice as a fermentation stimulant for lucerne silage. J Sci Food Agric. 1999;79:1285–1288. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjit N.K., Kung L., Jr. The effect of Lactobacillus buchneri, Lactobacillus plantarum, or a chemical preservative on the fermentation and aerobic stability of corn silage. J Dairy Sci. 2000;83:526–535. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(00)74912-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich L.J., Kung L. Effects of combining Lactobacillus buchneri 40788 with various lactic acid bacteria on the fermentation and aerobic stability of corn silage. Animal Feed Sci Technol. 2010;159:105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena J., Tanner R. Optimization of a corn steep medium for production of ethanol from synthesis gas fermentation by Clostridium ragsdalei. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;28:1553–1561. doi: 10.1007/s11274-011-0959-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt R., Kung L., Jr. The effects of Lactobacillus buchneri with or without a homolactic bacterium on the fermentation and aerobic stability of corn silages made at different locations. J Dairy Sci. 2010;93:1616–1624. doi: 10.3168/jds.2009-2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt R.J., Hu W., Mills J.A., Kung L., Jr. The development of lactic acid bacteria and Lactobacillus buchneri and their effects on the fermentation of alfalfa silage. J Dairy Sci. 2009;92:5005–5010. doi: 10.3168/jds.2008-1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira M., Wisbeck E., Hoch I., Jonas R. Production of glucose–fructose oxidoreductase and ethanol by Zymomonas mobilis ATCC 29191 in medium containing corn steep liquor as a source of vitamins. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001;55:442–445. doi: 10.1007/s002530000569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest P v, Robertson J., Lewis B. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J Dairy Sci. 1991;74:3583–3597. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78551-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Buckmaster D.R., Jiang Y., Hua J. Experimental study on baling rice straw silage. Int J Agric Biol Eng. 2011;4:20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg Z., Ashbell G., Hen Y., Azrieli A. The effect of applying lactic acid bacteria at ensiling on the aerobic stability of silages. J Appl Microbiol. 1993;75:512–518. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson J.M. In: Silage. Part 6: assessing silage quality. Chapter 19: analysis and clinical assessment of silage. Wilkinson J.M., editor. Chalcombe Publications; UK: 2005. pp. 198–208. [Google Scholar]

- Xing L., Chen L., Han L. The effect of an inoculant and enzymes on fermentation and nutritive value of sorghum straw silages. Bioresour Technol. 2009;100:488–491. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]