Abstract

This study aims to evaluate the effects of aflatoxins on growth performance and skeletal muscle of Cherry Valley meat male ducks as they grow and develop. One-day-old healthy meat male ducks (n = 180) were randomly divided into 2 groups; there were 6 replicates in each group and 15 ducks in each replicate. The control group was fed a basic diet, and the experimental group was fed a mold-exposed cottonseed meal diet containing aflatoxins instead of normal cottonseed meal. The experimental period was 35 days, and divided into two stages of 1 to 14 days (early stage) and 15 to 35 days (late stage). During the experimental period, live weight, breast muscle weight and thigh muscle weight of meat male ducks were measured weekly. Results showed as follows: 1) aflatoxins contained in the mold-exposed diet significantly reduced daily weight gain and feed intake, and increased feed-to-gain ratio of meat male ducks at different ages (P < 0.05); 2) the Gompertz equation (Wt = Wm exp {−exp [−B (t − t*)]}) could successfully fit the growth curve and growth and developmental patterns of skeletal muscles of Cherry Valley meat male ducks (R2 ≥ 0.97); 3) the relationship between chest muscle and live weight was the best described by a power regression and polynomial regression (R2 = 0.99); the relationship between live weight and thigh muscle weight was the best described by linear regression, polynomial regression, and power regression (R2 = 0.99); 4) aflatoxins in the mold-exposed diet significantly reduced live weight, breast muscle weight and thigh muscle weight of Cherry Valley meat male ducks at various ages; and 5) aflatoxins delayed the age at peak in growth of meat male ducks, and reduced weights at the peak for breast muscle, thigh muscle and whole body as well as the maximal daily weight gain. In summary, aflatoxins delayed growth of Cherry Valley meat male ducks and development of skeletal muscle.

Keywords: Aflatoxin, Cherry Valley duck, Skeletal muscle, Gompertz equation

1. Introduction

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) estimates that 25% of grain is contaminated with mycotoxins globally each year, and, on average, 2% is not edible. Ingestion of such contaminated grain can result in poisoning, disease and even death in a large number of animals, causing huge economic losses to the food industry and animal husbandry. Among these mycotoxins, the most serious contamination is caused by aflatoxins (AFs) (Feng et al., 2014). Aflatoxins are the secondary metabolite produced by Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus parasiticus, Aspergillus nomius and Aspergillus pseudotamarii, is extremely toxic, mutagenic and carcinogenic, and is recognized to be the most harmful mycotoxin. In recent years, AFs contamination in poultry feed have become increasingly serious, and severely affects the development of animal husbandry in China (Liu et al., 2015, Huang et al., 2014a, Huang et al., 2014b). Meat duck is one of the animals most sensitive to AFs. High levels of AFs can cause acute death in meat-type ducks, and prolonged exposure to low levels of AFs can induce chronic toxicity, resulting in their slow growth and reduced production performance (Shi et al., 2010, Lv et al., 2013, Xie et al., 2015). There are a vast number of ducks raised in China. According to FAO's statistical data, the worldwide inventory of meat ducks in 2013 reached 1.186 billion; and of these, 1.045 billion were in Asia and 695 million in China, accounting for 58.60% and 66.51% of the world duck inventory and Asian duck inventory, respectively. Duck carcass muscle is mainly distributed in breast and thigh, and the quality and yield of breast and thigh muscles constitute important factors affecting poultry production performance, and are primary characteristics to consider in poultry breeding. The present study aims to study the effects of AFs on growth performance and skeletal muscle of meat male ducks as they age and develop.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Cherry Valley meat ducklings were purchased from the hatchery of Xianghe Chia Tai Co., Ltd., and feeding trial was conducted in test base of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

The AFs in the mold-exposed diet were from moldy cottonseed meal, and high performance liquid chromatography-fluorescence detection (HPLC-FLD) was used for the determination of AFs content in mold-exposed cottonseed meal. The basal diet was corn-soybean meal, with nutritional value and diet type typical for a commercial Cherry Valley meat duck in China, and this was used as the reference; the diet was designed based upon the nutrient requirements published by the National Research Council (NRC) (2012) for meat ducks. The composition and nutrient content of the diet are shown in Table 1. The cottonseed meal in control diet was normal cottonseed meal, and the cottonseed meal in the test diet was mold-exposed cottonseed meal. The amounts of added cottonseed meal were all 8%, and diets were fed in the form of pellets.

Table 1.

Composition and nutrient levels of basal diets (air-dry basis).

| Item | Weeks 1 to 2 |

Weeks 3 to 5 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| control | treatment | control | treatment | |

| Ingredients, % | ||||

| Corn | 58.91 | 59.37 | 63.89 | 63.84 |

| Soybean meal | 23.32 | 22.68 | 15.12 | 14.58 |

| Soybean oil | 0.95 | 1.33 | 1.69 | 2.23 |

| Corn protein meal | 2.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 |

| Cottonseed meal | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 |

| Rapeseed meal | 2.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 |

| CaHPO4 | 1.80 | 1.91 | 1.70 | 1.82 |

| Limestone | 1.23 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.85 |

| NaCl | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| L-lysine | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.22 | 0.23 |

| DL-methionine | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.16 |

| Premix1 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Choline chloride | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Zeolite | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.40 |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Nutrient level, %2 | ||||

| ME, MJ/kg | 12.14 | 12.14 | 12.54 | 12.54 |

| CP | 19.98 | 20.03 | 18.11 | 18.23 |

| Ca | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.85 |

| Available P | 0.42 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.42 |

| Lysine | 1.12 | 1.10 | 0.89 | 0.93 |

| Methionine | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.45 | 0.42 |

| Threonine | 0.77 | 0.82 | 0.75 | 0.71 |

| Tryptophan | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.22 |

The premix provided the following per kg of diets: VA 5,000 IU, VD 800 IU, VE 10 IU, VK3 1 mg, VB1 1.5 mg, riboflavin 6 mg, nicotinic acid 22 mg, D-pantothenic acid 20 mg, VB6 2 mg, VB12 0.03 mg, folic acid 0.8 mg, Cu (as copper sulfate) 20 mg, Fe (as ferrous sulfate) 90 mg, Mn (as manganese sulfate) 70 mg, Zn (as zinc sulfate) 60 mg, I (as potassium iodide) 0.40 mg, Se (as sodium selenite) 0.30 mg.

Metabolizable energy was a calculated value, and the others were measured values.

The experimental results showed that AF content of the mold-exposed cottonseed meal used in this experiment was 1,337.21 μg/kg; while AF contents of control group at early and late stages were 0.65 and 0.62 μg/kg, respectively. The contents of AFs (B1, B2, G1, and G2) of the experimental group at early and late stages were 80.59, 20.60, 0.83, 0.34 μg/kg and 81.02, 20.65, 0.91, 0.36 μg/kg, respectively; no other mycotoxins were detected. The AF content of the diet for the experimental group was higher than the limit for meat ducks per in the “Hygienical standard for feeds” (2001) in China, whereas AFB1 contents at the early and late stages did not exceed 10.0 and 20.0 μg/kg, respectively.

2.2. Experimental design and feeding management

A total of 180 one-day-old Cherry Valley meat ducklings (male duck) were randomly divided into 2 treatment groups, and there were 6 replicates for each treatment and 15 male ducks for each replicate. The control and experimental groups were fed a basal diet and a mold-exposed diet, respectively, and initial body weight was not significantly different between the groups (P > 0.05). The ducklings were raised in battery cages, and warm air was used for brooding ducklings. During the trial period, male ducks had free access to food and water, regular desludging and sterilization were conducted, and a 24-h light was provided. The survival ratios of ducks in control and test group were 96.67% and 95.56%, respectively.

2.3. Determination of indicators

2.3.1. Production performance

The replicates were used as a unit to measure weights on days 7, 14, 21, 28, and 35 of the trial, and feeding was stopped 12 h before weighing; free access to water was provided. Live weight (LW) and feed consumption were recorded at various ages, and the average daily (weight) gain (ADG), average daily feed intake (ADFI) and feed-to-gain ratio (F:G) were calculated.

2.3.2. Determination of AF amounts

The contents of AFs (B1, B2, G1, and G2) in feed and feed raw materials were analyzed by HPLC-FLD, and results were expressed in total amounts of 4 AFs. Derivatization was performed using a post-photochemical derivatization column, which was purchased from Beijing Huaan Magnech Bio-Tech Co., Ltd.

2.3.3. Data collection

On 1, 7, 14, 21, 28, and 35 days of age, 1 male duck of average BW from each replicate was chosen, weighed and slaughtered by bleeding the left jugular vein after fasting for 12 h. Live weight, breast muscle weight (BMW), and thigh muscle weight (TMW) were recorded.

2.4. Data processing and analysis methods

The cumulative growth factors and average values of LW, BMW, and TMW in different treatment groups were calculated, and cumulative growth factors were actual values for all ages. The nonlinear regression method in SPSS 19.0 (2010, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL 60606-6307) was used to estimate parameters in the Gompertz model. The relationship between LW of meat male ducks and growth of skeletal muscle was studied by curve regression fitting, multiple regression analysis was conducted to model the relationship between skeletal muscle and LW, and the F-test was used to determine the significance of the curve-fitting equation. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to perform single-factor ANONA, followed by Duncan's multiple-range test, and P < 0.05 indicated significance. The growth and development curves for the LW and skeleton muscle of meat male ducks were plotted utilizing Origin 8.0 (Originlab corporation, Northampton MA 01060 in USA).

The Gompertz growth model was depicted as follows:

where t was age and an independent variable (d); Wt was body weight or body component weight at t days of age and a dependent variable (g); Wm was parameter of mature body weight or body component weight; B was parameter of the growth rate for the body weight or body component weight before maturity; and t* was age parameter of body weight or body component weight reaching maximal growth rate. Among these, the weight at the inflection point was 0.368Wm (i.e., Wm/e); the age at the inflection point was t*; and the maximal daily gain was Wm × B/e.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of AFs on growth performance of Cherry Valley meat male ducks

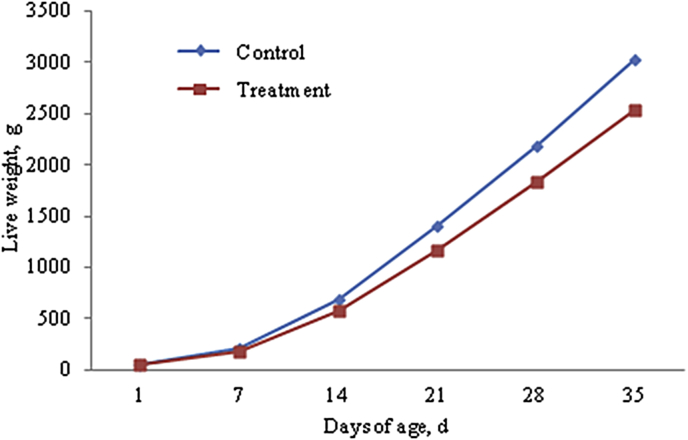

The effects of AFs on the performance of meat male ducks are shown in Table 2, Table 3. Compared with normal-diet group, presence of AFs in the diet significantly reduced weights of meat male ducks at 7, 14, 21, 28, and 35 days of age, significantly reduced daily weight gain and daily feed intake at different periods (1–7 days of age, 15–21 days of age, 22–28 days of age, 29–35 days of age, 1–14 days of age, and 15–35 days of age), and significantly increased their F:G at different ages (except for days 8–14; P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Effects of aflatoxins on the live weight (g) of ducks.

| Item | d 7 | d 14 | d 21 | d 28 | d 35 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 211.58 ± 9.46a | 688.28 ± 28.19a | 1,451.52 ± 68.14a | 2,237.67 ± 97.42a | 3,115.70 ± 150.50a |

| Treatment | 176.78 ± 4.92b | 573.40 ± 7.52b | 1,170.24 ± 12.18b | 1,834.53 ± 29.68b | 2,533.67 ± 31.92b |

a,b Within a row, means with different superscripts differ significantly (P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Effects of aflatoxins on the growth performance of ducks.

| Item | d 1-7 | d 8-14 | d 15-21 | d 22-28 | d 29-35 | d 1-14 | d 15-35 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADG, g | Control | 22.66 ± 1.25a | 64.78 ± 1.62a | 94.61 ± 0.86a | 87.59 ± 0.80a | 82.11 ± 1.60a | 43.72 ± 1.27a | 88.10 ± 0.76a |

| Treatment | 17.70 ± 0.69b | 54.36 ± 0.91b | 77.07 ± 1.22b | 76.32 ± 2.35b | 67.12 ± 0.60b | 36.03 ± 0.49b | 73.50 ± 1.03b | |

| ADFI, g | Control | 29.01 ± 1.89a | 91.31 ± 3.64a | 135.47 ± 2.10a | 196.19 ± 1.79a | 246.05 ± 1.36a | 60.16 ± 2.63a | 192.57 ± 1.06a |

| Treatment | 24.50 ± 0.78b | 78.35 ± 1.82b | 113.25 ± 3.24b | 184.11 ± 2.51b | 227.63 ± 3.02b | 51.43 ± 0.71b | 175.00 ± 2.30b | |

| F:G | Control | 1.28 ± 0.02a | 1.41 ± 0.03 | 1.43 ± 0.03a | 2.24 ± 0.02a | 3.00 ± 0.06a | 1.34 ± 0.02a | 2.22 ± 0.02a |

| Treatment | 1.39 ± 0.08b | 1.44 ± 0.04 | 1.47 ± 0.05b | 2.41 ± 0.09b | 3.39 ± 0.04b | 1.41 ± 0.04b | 2.43 ± 0.04b | |

a,b Within a row, means with different superscripts differ significantly (P < 0.05).

3.2. Effects of AFs on LW, BMW, and TMW of Cherry Valley meat male ducks at various ages

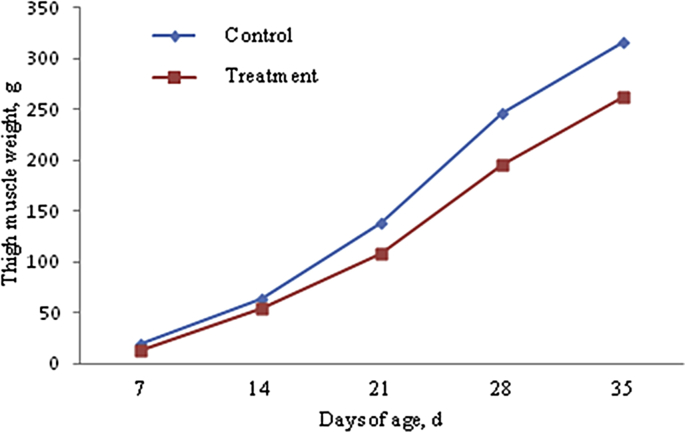

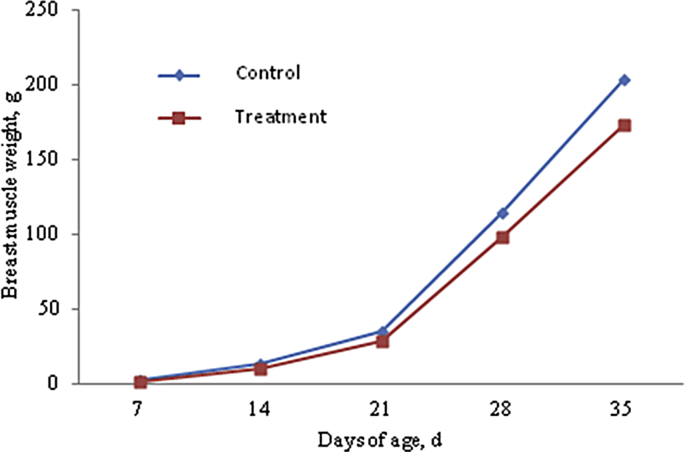

We observed from cumulative growth curves (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3 and Table 4), that LW, BMW and TMW of Cherry Valley meat male ducks increased with increasing age. The growth was relatively slow before 14 days of age, and gradually accelerated after that. Compared with control group, AFs in the mold-exposed diets in the experimental group significantly reduced LW, VMW, and TMW at different ages (P < 0.05), and significantly reduced their performance.

Fig. 1.

Accumulative growth curve of live weight of Cherry Valley male ducks.

Fig. 2.

Accumulative growth curve of thigh muscle weight of Cherry Valley male ducks.

Fig. 3.

Accumulative growth curve of breast muscle weight of Cherry Valley male ducks.

Table 4.

Effects of aflatoxins on the LW, BMW and TMW at different days of ducks.

| Days of age, d | LW |

BMW |

TMW |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Treatment | Control | Treatment | Control | Treatment | |

| 1 | 52.97 ± 0.99 | 52.89 ± 0.62 | ||||

| 7 | 206.91 ± 3.44a | 176.78 ± 4.92b | 2.26 ± 0.14a | 1.73 ± 0.06b | 18.78 ± 1.79a | 12.62 ± 0.49b |

| 14 | 688.28 ± 8.20a | 573.40 ± 7.52b | 13.46 ± 0.52a | 10.38 ± 0.38b | 64.02 ± 1.63a | 53.85 ± 1.99b |

| 21 | 1,404.35 ± 7.32a | 1,170.24 ± 2.18b | 34.47 ± 0.44a | 28.26 ± 0.72b | 138.10 ± 9.03a | 107.79 ± 3.15b |

| 28 | 2,184.33 ± 2.18a | 1,834.53 ± 9.68b | 114.23 ± 5.61a | 97.92 ± 2.12b | 246.77 ± 4.04a | 194.78 ± 2.93b |

| 35 | 3,032.37 ± 8.53a | 2,533.67 ± 7.92b | 203.09 ± 7.34a | 172.46 ± 4.73b | 315.46 ± 9.50a | 262.13 ± 5.56b |

LW = live weight; BMW = breast muscle weight; TMW = thigh muscle weight.

a,b Within a row, means with different superscripts differ significantly (P < 0.05).

3.3. Growth curve model for LW and skeletal muscle weight as related to age of Cherry Valley meat male ducks

A Gompertz-model curve was adopted to fit changes in LW, BMW and TMW vs. age of Cherry Valley meat male ducks, and estimated values of model parameters and goodness-of-fit (R2) are shown in Table 5. In our hands, Gompertz model provided a good fit for regression relationship of changes in LW, BMW and TMW as related to age of meat male ducks (R2 ≥ 0.97): compared with control group, experimental group exhibited diminutions in the maximal growth weight of meat male ducks (Wm), as well as the weight at the inflection point and the maximal daily weight gain when the maximal growth rate was attained.

Table 5.

Growth curve models of live weight and skeletal muscle weight with age for Cherry Valley male ducks.1

| Item | Model parameters |

R2 | P-value | Weight of inflexion, g | Max daily gain, g | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wm | B | t∗ | |||||

| LW | |||||||

| Control | 5,567.02 | 0.059 | 26.63 | 0.999 | <0.01 | 2,047.99 | 120.83 |

| Treatment | 4,673.87 | 0.059 | 26.69 | 0.999 | <0.01 | 1,719.42 | 101.45 |

| BMW | |||||||

| Control | 472.78 | 0.077 | 32.76 | 0.994 | <0.01 | 173.93 | 13.39 |

| Treatment | 344.92 | 0.088 | 30.79 | 0.996 | <0.01 | 126.89 | 11.17 |

| TMW | |||||||

| Control | 479.14 | 0.076 | 23.28 | 0.995 | <0.01 | 176.27 | 13.40 |

| Treatment | 457.07 | 0.066 | 26.00 | 0.997 | <0.01 | 168.15 | 11.10 |

LW = live weight; BMW = breast muscle weight; TMW = thigh muscle weight.

Wm = the parameter of mature body weight or body component weight; B = the parameter of the growth rate for the body weight or body component weight before maturity; t∗ = the age parameter of body weight or body component weight reaching the maximal growth rate; R2 = fitting degree of model.

3.4. Relative growth relationship between skeletal muscle development and LW of Cherry Valley meat male ducks

A regression curve (with SPSS 19.0) was used to fit the allometric growth relationships between LW and both BMW and TMW for Cherry Valley meat male ducks, and the established multiple regression equations are shown in Table 6, Table 7. With respect to results for the allometric growth equation for BMW and LW curve regression, power regression and polynomial regression provided the best fit (R2 = 0.99). With regard to results for the allometric growth equation for the TMW and LW curve regression, linear regression, polynomial regression and power regression provided the best fit (R2 = 0.99). We attained high significance levels with statistical F-test with respect to aforementioned results (P < 0.01).

Table 6.

Fitting degrees and parameters evaluation of regression model between BMW, TMW and LW of Cherry Valley male ducks of the control group.1

| Dependent | Independent | Model | Model parameters |

R2 | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b1 | b2 | b3 | Constant | |||||

| BMW | LW | Linearity regression | 12.92 | 553.65 | 0.93 | <0.01 | ||

| Logarithmic regression | 611.05 | −574.64 | 0.93 | <0.01 | ||||

| Polynomial regression | 48.29 | −0.38 | 0.001 | 112.49 | 0.99 | <0.01 | ||

| Power regression | 0.59 | 141.02 | 0.99 | <0.01 | ||||

| TMW | LW | Linearity regression | 9.12 | 74.56 | 0.99 | <0.01 | ||

| Logarithmic regression | 929.53 | −2,823.91 | 0.88 | <0.01 | ||||

| Polynomial regression | 14.95 | −0.05 | 0.001 | −70.00 | 0.99 | <0.01 | ||

| Power regression | 0.93 | 13.88 | 0.99 | <0.01 | ||||

LW = live weight; BMW = breast muscle weight; TMW = thigh muscle weight.

R2 is fitting degree of model; b1, b2, b3 are model parameters.

Table 7.

Fitting degree and parameters evaluation of regression model between BMW, TMW and LW of Cherry Valley male ducks of the treatment group.1

| Dependent | Independent | Model | Model parameters |

R2 | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b1 | b2 | b3 | Constant | |||||

| BMW | LW | Linearity regression | 12.66 | 470.91 | 0.93 | <0.01 | ||

| Logarithmic regression | 498.00 | −332.04 | 0.93 | <0.01 | ||||

| Polynomial regression | 49.09 | −0.47 | 0.002 | 107.16 | 0.99 | <0.01 | ||

| Power regression | 0.54 | 142.45 | 0.99 | <0.01 | ||||

| TMW | LW | Linearity regression | 9.28 | 86.23 | 0.99 | <0.01 | ||

| Logarithmic regression | 728.74 | −1,954.62 | 0.86 | <0.01 | ||||

| Polynomial regression | 12.90 | −0.03 | 0.001 | 3.15 | 0.99 | <0.01 | ||

| Power regression | 0.88 | 18.73 | 0.99 | <0.01 | ||||

LW = live weight; BMW = breast muscle weight; TMW = thigh muscle weight.

R2 is fitting degree of model; b1, b2, b3 are model parameters.

4. Discussions

4.1. Effects of AFs on the growth performance of meat male ducks

Acute mycotoxin poisoning rarely occurs in actual production; rather more common are chronically toxic effects of mycotoxins after livestock are fed a mold-exposed diet. Performance of livestock is apparently hindered after animals are fed diets which mycotoxin level exceeds the Hygienical standard for feeds in China (2001). Meat duckling is one of animals that are most sensitive to AFs, and their performance is more significantly affected by chronically toxic effects of mycotoxins.

Wen (2012) studied impacts of AFs on the growth of meat ducks by replacing normal corn with corn contaminated with different proportions of AFs. The experimental results showed that with increased replacement ratio, body weights of meat ducks at different ages were significantly reduced, and the most significant effect on growth was found in ducks younger than 35 days of age. Chen et al. (2014) investigated effects of different levels of AFB1 on 1- to 14-day-old meat ducks, and their results revealed that compared with the control group, duck body-weight gains were reduced by 10.9%, 31.7%, and 47.4% when the AFB1 contents in the diet were 0.11, 0.14, and 0.21 mg/kg, respectively. In addition, the body-weight gain of each duck was reduced by about 169 g for every 0.1 mg/kg increment in the dietary AF concentration. In our study, the mycotoxins in the mold-exposed cottonseed meal were primarily AFs, the concentration of which far exceeded the limit and reached 1.34 mg/kg. Our experimental results showed that AFs significantly reduced LW of meat male ducks at different ages.

Lv et al. (2013) added different levels of pure AFB1 (50.0, 100.0 and 150.0 μg/kg) to the basal diet, and found that AFB1 significantly reduced daily feed intake of meat ducks. Compared with control group, 100.0 and 150.0 μg/kg AFB1 treatments significantly increased F:G. Han et al. (2008) fed meat ducks with moldy rice containing different doses (20.0 and 40.0 μg/kg) of AFB1, and found decrease in duck feed intake and an increase in F:G. Wen et al. (2013) used naturally moldy corn (AF levels exceeding the limit) instead of normal corn to feed meat ducks and found significant decrease in duck feed intake and a significant increase in F:G. When the replacement ratio was 100%, duck mortality was significantly increased. In the present experiment, a moldy cottonseed meal significantly reduced feed intake, and significantly increased feed gain.

He et al. (2013) and Marchioro et al. (2013) also reported that AFs caused dramatic reduction in feed intake of meat ducks; reduced feed intake could then lead to decreases in body weight and weight gain. Yang et al. (2014) also found that AF reduced utilization efficiencies of meat ducks with respect to energy and protein feed. Feng et al. (2010) found that after meat ducks were fed moldy corn, suppression of duck feed intake was due to an increase in the content of serum leptin and a decrease in the content of serum neuropeptide Y; and that these are likely the factors involved in the reduction in duck performance caused by AFs. Therefore, naturally moldy feed or the addition of pure AFs appears to decrease the growth performance of meat ducks.

Studies have shown that the poisoning symptoms caused by feeding with naturally moldy feed are more severe than those arising from feed supplemented with a single pure toxin (Swamy et al., 2002). This may be due to the synergistic effects from a variety of toxins that often exist in naturally moldy feed, causing a greater impact on the growth performance of test animals than that observed from one toxin alone.

4.2. Effects of AFs on development of Cherry Valley meat male ducks

Growth-curve fitting analysis has become an important means by which to study how to divide the stages of animal growth and development and how to implement an appropriate nutritional system in livestock feed. Zhang et al. (2009) adopted different non-linear growth models to analyze weight data of white Muscovy ducks at an early age, and the data indicated that the Gompertz model produced the best fit. Zhu et al. (2007) studied Beijing ducks and also found that the Gompertz model was suitable for describing breeds with a fast early-growth rate. Therefore, we used the Gompertz model in this experiment as the growth model, and the Gompertz equation was fitted to the growth curve. The inflexion point-body weights at the maximal growth rate for the control and experimental groups were 2,047.99 and 1,719.42 g, respectively; and the maximal daily gains were 120.83 and 101.45 g, respectively. These results were different with those from previous study by Feng et al. (2010) who found that the inflexion point-body weights at the maximal growth rate were 1.354 and 1.432 g, respectively, which may caused by the difference in test material, diet or season, and others.

4.3. Effects of AFs on development of skeletal muscle in Cherry Valley meat male ducks

Bone is an early-maturing organ in poultry, with rapid growth and development at early ages and a slow growth rate at later stages of the growth period (Wang et al., 2014). There have been numerous studies on the patterns in growth and development of skeletal muscle with broilers as an animal model, but regarding bone, studies have shown that the fastest bone development in hens generally occurs in the first 10 weeks of age. The skeletal bone reaches 75%, 82%, and 90% of mature skeletal bones at 8, 10, and 12 weeks of age, respectively; at 20 weeks of age, all bone development is completed (Ono and Wakasugi, 1984). In our study, LW, BMW and TMW of Cherry Valley meat male ducks gradually increased concomitant with age, the cumulative growth curve exhibited a relatively flat slope, and growth was relatively slow before 14 days of age, gradually accelerating after that. The Gompertz model parameters showed that the inflection-point weights of BMW at the maximal growth rate in the control and experimental groups were 173.93 and 126.89 g, respectively, with the largest daily gains being 13.39 and 11.17 g. The inflection-point weights of TMW at the maximal growth rate in the control and experimental groups were 176.27 and 168.15 g, respectively, with the largest daily gains being 13.40 and 11.10 g. Our experimental results showed that the AFs in the mold-exposed diet administered to the experimental group reduced the slaughter performance of Cherry Valley meat male ducks, and affected development of their skeletal muscle. It should be noted that the present study targeted early growth curves (1–35 days of age) of Cherry Valley meat male ducks and development of their skeletal muscle, and was not meant to cover completely the entire poultry growth process. Therefore, the fitted model appears only to be suitable for the prediction of growth and development in 1- to 35-day-old Cherry Valley meat male ducks.

5. Conclusions

The AFs in the mold-exposed diet significantly decreased production performance of Cherry Valley meat male ducks. The Gompertz model provided a good fit for growth curve and development of skeletal muscles of meat male ducks. The relationship between breast muscle and live weight was the best described using a power regression and polynomial regression; the relationship between live weight and thigh muscle weight was the best described by using linear regression, polynomial regression, and power regression.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation program in Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (ASTIP).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

References

- Chen X., Horn N., Cotter P.F., Applegate T.J. Growth, serum biochemistry, complement activity, and liver gene expression responses of Peking ducklings to graded levels of cultured aflatoxin B1. Poult Sci. 2014;8:2028–2036. doi: 10.3382/ps.2014-03904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng G.D., Zhang K.Y., He J., Liu Y.F., Yin H.T. Effects of naturally mycotoxin-contaminated corn on growth curve of ducks. Feed Ind. 2010;14:42–44. [Google Scholar]

- Feng L., Yang D.M., Li H., Tian Y.Q., Zhao T.R., Zhang R.P. Survey on Pollution of aflatoxin B1 in foodstuffs. Parasitoses Infect Dis. 2014;3:117–119. [Google Scholar]

- Han X.Y., Huang Q.C., Li W.F., Jiang J.F., Xu Z.R. Changes in growth performance, digestive enzyme activities and nutrient digestibility of cherry valley ducks in response to aflatoxin B1 levels. Livest Sci. 2008;1:216–220. [Google Scholar]

- He J., Zhang K.Y., Chen D.W., Ding X.M., Feng G.D., Ao X. Effects of maize naturally contaminated with aflatoxin B 1 on growth performance, blood profiles and hepatic histopathology in ducks. Livest Sci. 2013;152(2):192–199. [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Xiao X.C., Wang S.K., Li J.S., He L.H., Li L.M. Contamination of aflatoxin B1 in feed and its harm on fishes (part I) Contemp Aquac. 2014;9:80–81. [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Xiao X.C., Wang S.K., Li J.S., He L.H., Li L.M. Contamination of aflatoxin B1 in feed and its harm on fishes (Part II) Contemp Aquac. 2014;10:81–82. [Google Scholar]

- Liu F.Z., Sun H.M., Lian X.H., Li C.F., Cong Q.X., Zhang T.T. Analysis of contamination status of aflatoxin B1 in feed and feedstuff in 2014. Guangdong Feed. 2015;3:45–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lv W.X., He J.H., Song H.G., Liu M.M., Jin X.L., Li J.B. Aflatoxin B1 affects growth, liver tissue structure and immune related gene expression of meat duckling. Chin J Animal Nutr. 2013;4:812–818. [Google Scholar]

- Marchioro A., Mallmann A.O., Diel A., Dilkin P., Rauber R.H., Blazquez F.J.H. Effects of aflatoxins on performance and exocrine pancreas of broiler chickens. Avian Dis. 2013;2:280–284. doi: 10.1637/10426-101712-Reg.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono T., Wakasugi N. Mineral content of quail embryos cultured in mineral-rich and mineral-free conditions. Poult Sci. 1984;63(1):159–166. doi: 10.3382/ps.0630159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi D.Y., Li P.F., Guo M.S., Liu N., Guo J.Y., Tang Z.X. Effects of different doses of aflatoxin B1 on growth of ducklings. Chin J Veterinary Med. 2010;4:22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Swamy H., Smith T.K., Macdonald E.J., Karrow N.A., Woodward B., Boermans H.J. Effects of feeding a blend of grains naturally contaminated with mycotoxins on swine performance, brain regional neurochemistry, and serum chemistry and the efficacy of a polymeric glucomannan mycotoxin adsorbent. J Animal Sci. 2002;12:3257–3267. doi: 10.2527/2002.80123257x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.C., Cai H.Y., Yan H.J., Chen X.L., Zhang S., Zhang A.H. Skeletal muscle growth, development and histological characteristics of Arbor Acres broilers. Chin J Animal Nutr. 2014;4:1085–1094. [Google Scholar]

- Wen Z.Y., Zheng P., Zhang K.Y., Ding X.M., Bai S.P., Peng X. Effects of AF-contaminated corn and adsorbents on growth performance, serum biochemical index and organ index. Chin J Animal Sci. 2013;3:49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Wen Z.Y. Sichuan Agricultural University; Ya'an in Sichuan province: 2012. Effects of aflatoxin contaminated corn and mycotoxin binder on performance and health status of Cherry Valley ducks. Master's Degree Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Xie Q., Sun M.J., Chang W.H., Liu Z.Y., Ma J.S., Liu G.H. Effects of aflatoxins and absorbents on growth performance and immune indices of meat ducks. Chin J Animal Nutr. 2015;1:204–211. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z.B., Wan X.L., YangANG W.R., Jiang S.Z., Zhang G.G., Johnston S.L. Effects of naturally mycotoxin-contaminated corn on nutrient and energy utilization of ducks fed diets with or without Calibrin-A. Poult Sci. 2014;9:2199–2209. doi: 10.3382/ps.2013-03392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.B., Duan X.J., Zhang Y.Y., Xu Q., Liao J., Wang C.B. Comparison on growth curve fitting of White Muscovy. China Animal Husb Veterinary Med. 2009;2:148–151. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X.Y., Hou S.S., Liu X.L., Yang X.G., Huang W. Comparison and analysis of growth curve model of Peking duck. Heilongjiang Animal Sci Veterinary Med. 2007;10:47–49. [Google Scholar]