Abstract

This experiment was conducted to investigate the effects of dietary arginine levels on growth performance, body composition, serum biochemical indices and resistance ability against ammonia-nitrogen stress in juvenile yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco). Five isonitrogenous and isolipidic diets (42% protein and 9% lipid) were formulated to contain graded levels of arginine (2.44%, 2.64%, 2.81%, 3.01% and 3.23% of diet), by supplementing L-Arginine HCl. Seven hundred juvenile yellow catfish with an initial average body weight of 1.13 ± 0.02 g were randomly divided into 5 groups with 4 replicates of 35 fish each and each group was fed one of the diets. After 56 d feeding, fish were exposed to 100 mg/L of ammonia-nitrogen for 72 h. The results showed that weight gain (WG) and specific growth rate (SGR) in 2.64% and 2.81% groups were significantly higher than those in 3.23% group (P < 0.05). The feed conversation ratio (FCR) in 2.64%, 2.81% and 3.01% groups was significantly decreased when compared with 3.23% group. The protein efficiency ratio (PER) in 2.64% group was significantly higher than that in 2.44% and 3.23% groups (P < 0.05). The condition factor (CF) of fish was significantly higher in 2.81% group than that in 2.44% group (P < 0.05). Dietary arginine levels had no significant effect on hepatosomatic index (HSI), viscerosomatic index (VSI), and whole-body dry matter, crude protein, crude lipid, ash contents, as well as serum total protein (TP), triglyceride (TG), glucose (GLU), urea nitrogen (UN) contents and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activities (P > 0.05). After the fish were challenged to ammonia-nitrogen for 72 h, their cumulative mortality rate in 2.81% group was significantly lower than that in 2.44% group (P < 0.05). The results suggested that dietary arginine level at 2.81% could optimize anti-ammonia-nitrogen stress ability of juvenile yellow catfish and a level of 3.23% arginine seemed to depress the growth performance of fish and decreased their tolerance to the ammonia-nitrogen stress under current study. A quadratic regression analysis based on WG indicated that the optimal dietary arginine requirement of juvenile yellow catfish was estimated to be 2.74% of the diet (6.45% of dietary protein) under current culture conditions.

Keywords: Arginine, Yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco), Growth performance, Body composition, Serum biochemical indices, Ammonia-nitrogen stress

1. Introduction

Yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco), belongs to Bagridae in Siluriformes, is a fish with particular flavor and rich nutrition (Huang et al., 2010). The fish fillet has no intermuscular bone and tender muscle (Li et al., 2009). Because of its excellent meat quality, yellow catfish not only has good sales in China, but also has a potential market in Japan, South Korea and Southeast Asia (Pan et al., 2008). Recently, the production of yellow catfish has been largely increased in order to meet the market demands in China (Gao et al., 2011) and they tend to be cultured in intensive conditions, which is around 3,000 kg/667 m2. However, in the high density of factory farming water, the ammonification of bait and fish excreta will produce large amounts of ammonia nitrogen, and excessive ammonia nitrogen will result in food intake decreased, growth reduction and immune suppression, stress for a long time even cause death (Shi et al., 2015).

As one of the essential amino acids for fish, arginine takes part in many metabolic reactions in animal bodies, such as the synthesis of protein, carbamide and ornithine, the metabolism of glutamic acid and proline, the synthesis of creatine and polyamine, and the excretion of insulin and glucagon (Luo et al., 2004). Previous studies have shown that dietary arginine supplementation can improve the growth performance (Pohlenz et al., 2014), enhance immunity (Cheng et al., 2011), and reduce the environmental stress (Oehme et al., 2010) of fish. The arginine requirements among different species of fish have been shown to vary from 1.0% to 3.1% of dietary, which is possibly affected by fish species and sizes, dietary protein sources and levels, management methods, feeding strategy and experimental conditions (NRC, 2011, Ren et al., 2013, Zhou et al., 2015). The arginine requirement of yellow catfish was 2.38% to 2.74% of the dry diet (Zhou et al., 2015).

To our knowledge, there is no information available concerning the effect of dietary arginine on the anti-ammonia-nitrogen stress ability in yellow catfish. This study was conducted to investigate the effects of dietary arginine levels on growth performance, body composition, serum biochemical indices and resistance ability against ammonia-nitrogen stress in yellow catfish.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Experimental diets

Five isonitrogenous and isolipidic diets (Table 1) (42% protein and 9% lipid), using fishmeal and soybean as main protein sources, wheat flour as main carbohydrate source, fish oil and soybean oil as main lipid sources, were formulated to contain 5 graded levels of arginine (2.44%, 2.64%, 2.81%, 3.01% and 3.23% of diet), by supplementing L-Arginine HCl (the purity ≥ 99%, Ningbo Daxie Development Zone Haide Amino Acid Industry Co., Ltd., Ningbo, China). The diets were kept isonitrogenous by adding different levels of alanine before pelleting. Final arginine concentrations of the 5 experimental diets were measured after acid hydrolysis using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (LC1260, Agilent Technologies Inc., Germany) equipped with Agilent ZORBAX Eclipse Plus C18 columns (150 mm × 5 μm, Australia). Dietary protein and lipid levels referenced to the previous formula in our lab (Zhao et al., 2015). The arginine levels were chosen refer to the recommended concentration of Zhou et al., (2015) and adjusted according to the fish size and experimental conditions. All the ingredients were ground into powder through 60-mesh, weighed accurately according to the formula, and then mixed before adding fish oil and soybean oil into kneading machine (NH-10, Science and Technology Industrial General Factory of South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China). The feed ingredients were thoroughly mixed with appropriate amount of water in a strong stirrer (B20, Guangzhou Panyu Lifeng Food Machinery Factory, Guangzhou, China), then processed into 1.5 mm diameter strip using twin screw extruder (SLX-80, Science and Technology Industrial General Factory of South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China). The resultant strips were made into granule at granulator (G-500, Science and Technology Industrial General Factory of South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China) and then dried at the temperature of 55°C for 6 h, stored at −20°C after natural cooling. The proximate composition and amino acid composition of each diet are presented in Table 1, Table 2.

Table 1.

Formulation and proximate composition of experimental diets (air-dry basis, %).

| Item | Dietary arginine levels, % |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.44 | 2.64 | 2.81 | 3.01 | 3.23 | |

| Ingredients | |||||

| Peru fish meal1 | 25.00 | 25.00 | 25.00 | 25.00 | 25.00 |

| Soybean meal1 | 30.00 | 30.00 | 30.00 | 30.00 | 30.00 |

| Rapeseed meal1 | 9.00 | 9.00 | 9.00 | 9.00 | 9.00 |

| Corn gluten meal1 | 6.00 | 6.00 | 6.00 | 6.00 | 6.00 |

| Wheat flour1 | 20.50 | 20.66 | 20.82 | 20.98 | 21.14 |

| Fish oil1 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 |

| Soybean oil1 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 |

| Vitamin premix2 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Mineral premix3 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Ca(H2PO4)21 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 1.50 |

| Vitamin C ester1 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Choline chloride1 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| L-Arginine HCl | 0.00 | 0.24 | 0.48 | 0.72 | 0.96 |

| Alanine1 | 2.00 | 1.60 | 1.20 | 0.80 | 0.40 |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Proximate composition | |||||

| Crude protein | 42.8 | 42.0 | 42.6 | 42.4 | 42.6 |

| Crude lipid | 8.9 | 9.0 | 9.3 | 8.7 | 8.7 |

| Ash | 7.9 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 7.9 |

| Moisture | 7.0 | 6.7 | 6.8 | 6.9 | 6.8 |

Fishtech Fisheries Science & Technology Company, LTD, Institute of Animal Science, Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Guangzhou, China).

The vitamin premix was provided by Fishtech Fisheries Science & Technology Company, LTD, Institute of Animal Science, Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Guangzhou, China). One kilogram of vitamin premix contained the following: VA 3,200,000 IU, VB1 4 g, VB2 8 g, VB6 4.8 g, VB12 0.016 g, VD 1,600,000 IU, VE 16 g, VK 4 g, nicotinic acid 28 g, calcium pantothenate 16 g, folic acid 1.28 g, inositol 40 g, biotin 0.064 g. Moisture ≤10%.

The mineral premix was provided by Fishtech Fisheries Science & Technology Company, LTD, institute of Animal Science, Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Guangzhou, China). One kilogram of mineral premix contained the following: MgSO4·H2O 12 g, Ca(IO3)2 9 g, KCl 36 g, Met-Cu 1.5 g, ZnSO4·H2O 10 g, FeSO4·H2O 1 g, Met-Co 0.25 g, NaSeO3 0.003 6 g. Moisture ≤10%.

Table 2.

Amino acids composition of experimental diets (air-dry basis, %).

| Item | Dietary arginine levels, % |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.44 | 2.64 | 2.81 | 3.01 | 3.23 | |

| Essential amino acids | |||||

| Arg | 2.44 | 2.64 | 2.81 | 3.01 | 3.23 |

| His | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.98 |

| Ile | 1.75 | 1.76 | 1.75 | 1.76 | 1.76 |

| Leu | 3.32 | 3.38 | 3.36 | 3.36 | 3.36 |

| Lys | 2.46 | 2.50 | 2.48 | 2.47 | 2.49 |

| Met | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.69 |

| Phe | 1.85 | 1.88 | 1.86 | 1.88 | 1.87 |

| Thr | 1.61 | 1.62 | 1.61 | 1.62 | 1.62 |

| Val | 2.01 | 2.02 | 2.02 | 2.02 | 2.02 |

| Non-essential amino acids | |||||

| Ala | 4.36 | 4.02 | 3.60 | 3.21 | 2.80 |

| Asp | 3.55 | 3.60 | 3.58 | 3.58 | 3.59 |

| Glu | 7.70 | 7.85 | 7.78 | 7.81 | 7.81 |

| Gly | 2.22 | 2.24 | 2.22 | 2.24 | 2.23 |

| Ser | 2.08 | 2.10 | 2.10 | 2.11 | 2.10 |

| Tyr | 1.16 | 1.20 | 1.15 | 1.18 | 1.18 |

2.2. Fish and experimental conditions

The feeding trial was conducted in an indoor re-circulating aquaculture system at Animal Science Research Institute of Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Guangzhou, China). Experimental fish were obtained from Sand Fishery Base in Qingyuan city of Guangdong Province (Qingyuan, China). The circling waterflow rate in each aquarium was maintained at 1.5 L/min. Prior to the feeding trial, the fish were fed a commercial diet (42% protein and 9% lipid) twice daily (08:30 and 18:30) for 2 weeks to acclimate to the experimental conditions. Similar sized juvenile yellow catfish with an initial average body weight of 1.13 ± 0.02 g were selected and randomly distributed into twenty 330-L cylindrical fiberglass tanks (the water volume was 300 L) at 35 fish per tank. Each diet was randomly assigned to 4 tanks. Fish were fed 2 times daily at 08:30 and 18:30, and feeding level was 5% to 6% of body weight, according to Li et al., (2015). Diet amounts consumed by the fish in each tank were recorded daily, and adjusted according to the amounts consumed the day before. All tanks were supplied with freshwater with the exchange rate of 1/3 tank volume weekly. The feeding trial lasted for 56 days. During the experimental period, the water temperature was 29.5–33.0°C, pH level was maintained within the range of 7.4 to 7.9, ammonia nitrogen level remained below 0.20 mg/L, the content of nitrite was lower than 0.01 mg/L, and dissolved oxygen content remained above 6.0 mg/L. The feeding trial was completed under a natural light and dark cycle.

2.3. Sample collections

At the end of the feeding trial, all fish were fasted for 24 h, and then the fish in each tank were individually weighed and calculated for the survival rate (SR). Three fish in each tank were anesthetized with tricaine methane sulfonate (MS-222) at 120 mg/L, and then stored at −20°C for the analysis of whole body proximate composition. Five fish in each tank were used to determine hepatosomatic index (HSI), viscerosomatic index (VSI) and condition factor (CF) by obtaining the body weight, body length, liver weight and visceral weight. Ten representative fish from each tank were anesthetized and collected blood samples from the caudal vein. After clotted at room temperature for 4 h, serum was obtained by centrifugation (1,342 × g, 10 min, 4°C) and stored at −80°C for analysis. The methods for serum preparation referenced to (Niu et al., 2015).

2.4. Index determination

2.4.1. Growth performance calculation

The parameters were calculated as follows:

| SR (%) = 100 × final number of fish/initial number of fish; |

| Weight gain (WG, %) = 100 × [final body weight (g) − initial body weight (g)]/initial body weight (g); |

| Specific growth rate (SGR, %/d) = 100 × [Ln final individual weight (g) − Ln initial individual weight (g)]/number of feeding days; |

| Feed conversion ratio (FCR) = dry diet fed (g)/wet weight gain (g); |

| Protein efficiency ratio (PER) = 100 × wet weight gain (g)/protein fed (g); |

| CF (g/cm3) = 100 × body weight (g)/body length (cm)3; |

| HSI (%) = 100 × liver weight (g)/body weight (g); |

| VSI (%) = 100 × viscera weight (g)/body weight (g). |

2.4.2. Proximate composition analysis

All experimental diets and fish samples were analyzed in duplicate for proximate composition following the standard methods (AOAC, 1995). Moisture was determined by oven drying to a constant weight at 105°C. Crude protein (N × 6.25) was determined by the Kjeldahl method using a semi-automatic Kjeldahl System after acid digestion. Crude lipid was determined by using the Soxhlet extraction method. Crude ash was determined after burning at 550°C in a muffle furnace.

2.4.3. Serum biochemical indices analysis

Serum total protein (TP), triacylglycerol (TG), glucose (GLU), urea nitrogen (UN) contents and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activities were analyzed using Roche Kit and an automatic blood analyzer (Hitachi 7170A, Japan) in Kingmed Diagnostics (Guangzhou, China).

2.5. Ammonia-nitrogen stress test

After a 56 d feeding trial, fourteen fish were randomly selected from each tank for an ammonia-nitrogen stress test using ammonia chloride. During the test, the fish were not fed. The concentration of un-ionized ammonia and the calculation method as described by to Li et al. (2009). Ammonium chloride solution was poured into each tank of 150 L to set the level of total ammonia nitrogen at 100 mg/L, and the concentration of un-ionized ammonia was 2.65 mg/L (pH = 7.52; water temperature = 30.5°C). During the stress test, water temperature, pH level, and ammonia nitrogen concentration were determined every 6 h, and adjust the concentration of non-ionic ammonia according to the results using ammonium chloride solution. Mortality was recorded every 6 h during the period of 72 h stress test and dead fish were removed. The cumulative mortality rate (CMR) was calculated as follows:

| CMR (%) = 100 × number of death fish after stress test/number of fish before stress test. |

2.6. Statistical analysis

All data were presented as means ± SD, n = 4, and analyzed using SPSS 20.0 (Chicago, USA) for Windows. The data were analyzed by homogeneity test of variances first. Data accorded with homogeneity of variance were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance and performed using Tukey's test for multiple comparison if there was a significant difference, or using Dunnett's T3 for multiple comparison. The statistical significance was examined at P < 0.05. The dietary arginine requirement for yellow catfish was estimated using the quadratic regression method using the SigmaPlot statistical software program (version 10.0).

3. Results

3.1. Effect of dietary arginine levels on growth performance of yellow catfish

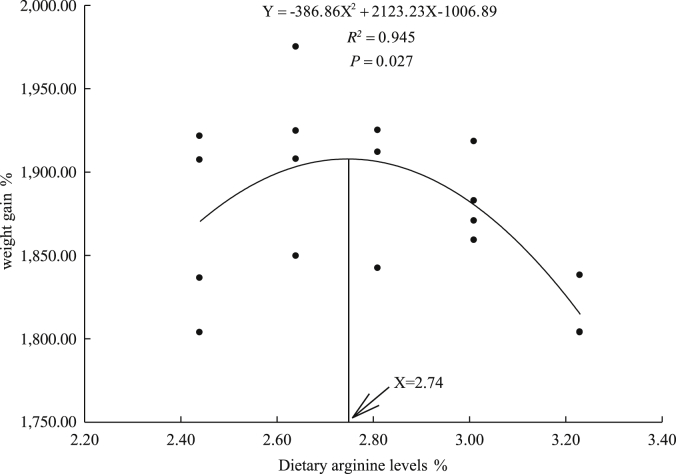

The SR for all treatments was 100%, and no pathological or abnormal condition were appeared during the feeding trial. The effects of dietary arginine levels on WG, SGR, FCR, PER, CF, HSI and VSI are presented in Table 3. The WG and SGR in 2.64% and 2.81% groups were significantly higher than those in 3.23% group (P < 0.05). The FCR in 2.64%, 2.81% and 3.01% groups was significantly decreased when compared with 3.23% group (P < 0.05). The PER in 2.64% group was significantly higher than that in 2.44% and 3.23% groups (P < 0.05). The CF of fish was significantly higher in 2.81% group than that in 2.44% group (P < 0.05). Dietary arginine levels had no significant effects on HSI and VSI. A quadratic regression analysis on WG against dietary arginine levels indicated that the optimal dietary arginine requirement of juvenile yellow catfish was estimated to be 2.74% of the diet (6.45% of dietary protein) (Fig. 1).

Table 3.

Effects of dietary arginine levels on growth performance of yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco).

| Item | Dietary arginine levels, % |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.44 | 2.64 | 2.81 | 3.01 | 3.23 | |

| Initial weight, g | 1.13 ± 0.01 | 1.13 ± 0.01 | 1.15 ± 0.01 | 1.12 ± 0.02 | 1.14 ± 0.02 |

| Final weight, g | 22.27 ± 0.74ab | 22.79 ± 0.68b | 22.86 ± 0.54b | 22.14 ± 0.61ab | 21.73 ± 0.34a |

| WG, % | 1,867.03 ± 56.36ab | 1,914.04 ± 51.73b | 1,892.88 ± 44.43b | 1,882.52 ± 25.63ab | 1,815.09 ± 19.76a |

| SGR, %/d | 5.32 ± 0.05ab | 5.36 ± 0.05b | 5.34 ± 0.04b | 5.32 ± 0.01ab | 5.27 ± 0.02a |

| FCR | 0.79 ± 0.02ab | 0.77 ± 0.02a | 0.78 ± 0.02a | 0.78 ± 0.01a | 0.81 ± 0.01b |

| PER | 2.96 ± 0.09ab | 3.09 ± 0.08c | 3.01 ± 0.07abc | 2.99 ± 0.02abc | 2.89 ± 0.03a |

| CF, g/cm3 | 2.40 ± 0.06a | 2.41 ± 0.10a | 2.69 ± 0.16b | 2.51 ± 0.02a | 2.42 ± 0.09a |

| HSI, % | 1.35 ± 0.09a | 1.36 ± 0.07a | 1.33 ± 0.06a | 1.19 ± 0.08a | 1.22 ± 0.19a |

| VSI, % | 7.25 ± 0.39a | 7.78 ± 0.47a | 7.57 ± 0.60a | 8.09 ± 0.13a | 7.52 ± 0.18a |

WG = weight gain; SGR = specific growth rate; FCR = feed conversion ratio; PER = protein efficiency ratio; CF = condition factor; HSI = hepatosomatic index; VSI = viscerosomatic index.

a,b,c In the same row, values with no or the same letter superscripts mean no significant difference (P > 0.05), and with different letter superscripts mean significant difference (P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Relationship between dietary arginine levels and weight gain of yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco).

3.2. Effect of dietary arginine levels on body composition of yellow catfish

The contents of dry matter, crude protein, crude lipid and ash in the whole body were not significantly affected by dietary arginine levels (P > 0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effects of dietary arginine levels on body composition of yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco) (wet weight, %).

| Item | Dietary arginine levels, % |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.44 | 2.64 | 2.81 | 3.01 | 3.23 | |

| Dry matter | 25.2 ± 0.4 | 25.5 ± 0.6 | 25.3 ± 0.7 | 25.2 ± 0.6 | 25.5 ± 0.9 |

| Crude protein | 15.1 ± 0.2 | 15.2 ± 0.3 | 15.3 ± 0.2 | 15.2 ± 0.3 | 15.2 ± 0.6 |

| Crude lipid | 5.5 ± 0.2 | 5.9 ± 0.2 | 6.0 ± 0.3 | 5.4 ± 0.4 | 5.6 ± 0.8 |

| Ash | 3.2 ± 0.0 | 3.4 ± 0.0 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 3.3 ± 0.2 |

In the same row, values with no letter superscripts mean no significant difference (P > 0.05).

3.3. Effect of dietary arginine levels on serum biochemical indices of yellow catfish

Table 5 showed that dietary arginine levels had no significant effect on serum TP, TG, GLU, UN contents and AST, ALT activities (P > 0.05). The serum TP contents were increased with the increasing of dietary arginine levels.

Table 5.

Effects of dietary arginine levels on serum biochemical indices of yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco).

| Item | Dietary arginine levels, % |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.44 | 2.64 | 2.81 | 3.01 | 3.23 | |

| TP, g/L | 25.43 ± 0.57 | 25.63 ± 0.35 | 25.68 ± 0.46 | 25.90 ± 0.65 | 25.90 ± 0.70 |

| TG, mmol/L | 5.64 ± 1.06 | 5.22 ± 1.67 | 5.86 ± 0.27 | 5.22 ± 1.36 | 5.86 ± 1.36 |

| GLU, mmol/L | 6.58 ± 0.52 | 6.94 ± 0.49 | 7.09 ± 0.88 | 6.76 ± 0.93 | 7.16 ± 0.38 |

| UN, mmol/L | 0.35 ± 0.06 | 0.30 ± 0.00 | 0.30 ± 0.08 | 0.38 ± 0.05 | 0.33 ± 0.05 |

| AST, U/L | 209.25 ± 14.24 | 220.25 ± 26.99 | 216.00 ± 15.43 | 208.75 ± 17.37 | 228.50 ± 14.82 |

| ALT, U/L | 7.75 ± 2.06 | 8.00 ± 1.63 | 8.25 ± 1.26 | 7.50 ± 1.00 | 8.75 ± 0.96 |

TP = total protein; TG = triacylglycerol; GLU = glucose; UN = urea nitrogen; AST = aspartate aminotransferase; ALT = alanine aminotransferase.

In the same row, values with no letter superscripts mean no significant difference (P > 0.05).

3.4. Effect of dietary arginine levels on anti-ammonia-nitrogen stress ability of yellow catfish

From Table 6, it was found that after a 72 h ammonia nitrogen stress test, compared with 2.44% group, the CMR of 2.81% group was significantly decreased (P < 0.05).

Table 6.

Effects of dietary arginine levels on the cumulative mortality rate after 72 h ammonia-nitrogen stress test of yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco).

| Item | Dietary arginine levels, % |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.44 | 2.64 | 2.81 | 3.01 | 3.23 | |

| Stressed fish per replication | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| Cumulative mortality, % | 57.1 ± 25.8b | 42.9 ± 7.1ab | 12.5 ± 14.7a | 25.0 ± 25.1ab | 42.9 ± 7.1ab |

a,b In the same row, values with no letter superscripts mean no significant difference (P > 0.05).

4. Discussion

Arginine can participate in the synthesis of protein and polyamine to promote animal growth (Wan et al., 2006). Previous studies have indicated that arginine can improve the growth performance of fish (Alam et al., 2002, Buentello and Gatlin, 2000, Farhat and Khan, 2012, Wang et al., 2015). According to the results in this study, WG, SGR, FCR and PER of yellow catfish were achieve the best in 2.64% group. In the present study, the SGR of yellow catfish was 5.27 to 5.36%/d, higher than the values reported by Li et al. (2016) (1.82 to 1.99%/d), Zhou et al. (2015) (2.85 to 3.23%/d) and Zhao et al. (2015) (3.75 to 3.94%/d), which is possibly affected by the initial weight of fish, dietary nutrient levels and feeding management. A quadratic regression analysis on WG against dietary arginine levels indicated that the optimal dietary arginine requirement of juvenile yellow catfish was estimated to be 2.74% of the diet (6.45% of dietary protein). The optimal requirement level was within the range of reported values from 3.8% to 8.1% protein of different species (NRC, 2011, Tu et al., 2015), but higher than the result (5.29% of dietary protein) in yellow catfish (2.00 ± 0.02 g) at the nutrition levels of 45% protein and 7% lipid of a 84-day feeding trial (Zhou et al., 2015). The reason for the difference may be due to the fish sizes, dietary protein levels, culture cycle and other factors. The results of the previous studies on arginine requirements of aquatic animals showed that the requirements of some marine fish varied between 6.20% and 7.74% of dietary protein (Ren et al., 2014, Yue et al., 2013, Lin et al., 2015, Zhou et al., 2010, Zhou et al., 2012b). And the requirements of some freshwater fish varied between 4.08% and 7.23% of dietary protein (Ahmed, 2013, Zhou et al., 2012a, Wang et al., 2015, Khan and Abidi, 2011, Ren et al., 2013, Liao et al., 2014). A comparison between the 2 types of results indicated that the arginine requirements of marine fish were higher than those of freshwater fish. However, its influencing factors and principle were still unknown, and further research is needed.

In this study, with the further increasing of dietary arginine levels, the negative influence on WG, SGR, FCR and PER was observed, and this was similar to the results reported for stinging catfish (Farhat and Khan, 2012), India major carp (Cirrhinus mrigala) (Ahmed and Khan, 2004), cobia (Ren et al., 2014) and nile tilapia (Yue et al., 2013). The study in mammals has pointed that the reduced growth in animal fed diets with excessive arginine may be due to the antagonism between lysine and arginine, but the mechanism in fish is still far from clear (Luo et al., 2004). Lysine–arginine antagonism was shown to exist in atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) (Berge et al., 1997) and blunt snout bream (Liao et al., 2014). However (Alam et al., 2002) and (Zhou et al., 2015) showed that no competitive inhibition was found between arginine and lysine on Japanese flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) or yellow catfish.

In this study, dietary arginine levels had no significant effects on the HSI and VSI of yellow catfish, and the CF in 2.81% group was significantly increased when compared with 2.44% group. The results were similar to the report in 2 different sizes of gibel carp (Carassis auratus gibelio var. CAS III) (Tu et al., 2015). However, Lin et al. (2015) pointed that HSI, VSI and CF of golden pompano were not significantly affected by dietary arginine levels. Farhat and Khan (2012) considered that the increasing of dietary arginine levels can significantly reduce the HSI and increase the CF, but no significant effect on VSI of stinging catfish. Different results showed that the HSI, VSI and CF of fish were not only related to the levels of dietary arginine, but also affected by the species and size, management and experimental conditions.

Whole body composition of yellow catfish was not significantly affected by dietary arginine levels, which agreed with the reports in blunt snout bream (Ren et al., 2013) and grouper (Epinephelus coioides) (Luo et al., 2007). However, other studies indicated that the protein content in the whole body increased with dietary arginine level increasing and decreased significantly when dietary arginine was higher than the optimal requirement (Tu et al., 2015, Zhou et al., 2012b). The reason for the different results may be due to that arginine can be digested and absorbed by fish and deposited in the body, while excessive arginine will not be used or even had an inhibiting effect. At present, the mechanism of the effect of arginine on the body protein of fish has not been elucidated, it may be explained through the comparison of an arginine deficiency group.

The serum biochemical can reflect the health status, nutrition status and the adaptability to environment when fish occurring physiological or pathological changes affected by external factors (Shi et al., 2012). Some researchers held that the change of fish serum biochemical indices might be caused by stress, or by some change of amino acids in diet (Lin et al., 2015). In this study, there was no significant effect of dietary arginine levels on serum TG, which agrees with previous finding in red sea bream (Pagrus major) (Rahimnejad and Lee, 2014) and golden pompano (Lin et al., 2015). The AST and ALT are generally used as indicators of cellular damage both in mammals and in fishes (Olsen et al., 2005). The result of the present study showed that dietary arginine levels had no damage to the liver of yellow catfish. The content of serum UN can reflect the balance of protein and amino acid metabolism in fish. Alam et al. (2002) found that the content of UN in serum was affected by the levels of dietary arginine. This study had a different result, which may be caused by the different of fish species, culture cycle, dietary protein and the arginine levels.

Some studies have showed that the excessive ammonia nitrogen in the environment can affect the immune system (Yue et al., 2010), also damage the gill, liver, kidney and other organs of the fish (Zhang et al., 2015). In this study, appropriate of dietary arginine level can reduce the CMR after ammonia nitrogen stress, and the results was similar to that of promoting the growth. This agrees to the conclusion of that the growth rate of fish was often related to the disease resistance (Lin et al., 2015). The reason for improving the ability of anti-ammonia nitrogen stress in fish may be related to the effect of arginine and its metabolites in immune regulation and immune defense (Sun et al., 2014). The role of arginine in the regulation of immune regulation in vivo is mainly carried through the nitric oxide (NO) pathway and the arginine pathway. The NO pathway means that the citrulline and NO derived from oxidation of arginine catalyzed by nitric oxide synthase (NOS). And NO is not only the effector molecule of tumor immunity and microbial immunity, but also the regulatory factors of variety of immune cells. In addition, the synthesis and metabolic pathway of arginine involved in the detoxification pathway of fish to ammonia nitrogen, which means that the relationship between arginine and ammonia nitrogen metabolism related enzymes (glutamate dehydrogenase, glutamine synthetase and arginase) is worth further research. At present, study about arginine on anti-ammonia-nitrogen stress ability has not been reported, and the mechanism needs to be further studied.

5. Conclusions

In summary, dietary arginine level at 2.81% could optimize anti-ammonia-nitrogen stress ability of juvenile yellow catfish and a level of 3.23% arginine seemed to depress the growth performance of fish and decreased their tolerance to the ammonia-nitrogen stress under current study. A quadratic regression analysis on weight gain rate against dietary arginine levels indicated that the optimal dietary arginine requirement of juvenile yellow catfish was estimated to be 2.74% of the diet (6.45% of dietary protein).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31402307) and the construction of public service platform for the evaluation of the value of aquatic feed and feed additives in Guangdong Province (2015A040404033).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

References

- Ahmed I., Khan M.A. Dietary arginine requirement of fingerling India major carp, Cirrhinus mrigala (Hamilton) Aquac Nutr. 2004;10:217–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed I. Dietary arginine requirement of fingerling Indian catfish (Heteropneustes fossilis, Bloch) Aquac Int. 2013;21:255–271. [Google Scholar]

- Alam M.S., Teshima S.I., Koshio S., Ishikawa M. Arginine requirement of juvenile Japanese flounder Paralichthys olivaceus estimated by growth and biochemical parameters. Aquaculture. 2002;205:127–140. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC) 16th ed. Association of Official Analytical Chemists; Arlington, VA: 1995. Official methods of analysis of official analytical chemists international. [Google Scholar]

- Berge G.E., Lied E., Sveier H. Nutrition of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar): the requirement and metabolism of arginine – relation to branched-chain amino acid antagonism. Comp Biochem Physiology. 1997;117:501–509. [Google Scholar]

- Buentello J.A., Gatlin D.M., III The dietary arginine requirement of channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) is influenced by endogenous synthesis of arginine from glutamic acid. Aquaculture. 2000;188:311–321. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z.Y., Buentello A., Gatlin D.M., III Effects of dietary arginine and glutamine on growth performance, immune responses and intestinal structure of red drum, Sciaenops ocellatus. Aquac. 2011;319:247–252. [Google Scholar]

- Farhat, Khan M.A. Effects of dietary arginine levels on growth, feed conversion, protein productive value and carcass composition of stinging catfish fingerling Heteropneustes fossilis (Bloch) Aquac Int. 2012;20:935–950. [Google Scholar]

- Gao C., Yang R.B., Hu W.B., Wang J. Ontogeny of the stomach in yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco): detection and quantification of pepsinogen and H+/K+ -ATPase gene expression. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 2011;97:20–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0396.2011.01238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Yang S., Qin Z.B., Wei W.Y., Feng J. Comparative study about flesh contents and nutrient values in brown bullhead, loach and darkbarbel catfish. Acta Hydrobiol Sin. 2010;34:990–997. [Google Scholar]

- Khan A.M., Abidi S.F. Dietary arginine requirement of Heteropneustes fossilis fry (Bloch) based on growth, nutrient retention and haematological parameters. Aquac Nutr. 2011;17:418–428. [Google Scholar]

- Li B., Fan Q.X., Zhang L., Fang W., Yang K., Sun C.J. Acute toxic effects of ammonia and nitrite on yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco) at different dissolved oxygen levels. Freshw Fish. 2009;39:31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Lai H., Li Q., Gong S.Y., Wang R.X. Effects of dietary taurine on growth, immunity and hyperammonemia in juvenile yellow catfish Pelteobagrus fulvidraco fed all-plant protein diets. Aquaculture. 2016;450:349–355. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.J., Huang Y.H., Wang W.M., Cao J.M., Wang G.X., Zhao H.X. Effects of dietary β-glucan on serum immunity, antioxidant indices, and kidney cytokines of juvenile yellow catfish, Pseudobagrus fulvidraco. Feed Res. 2015;20 49–54+58. [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y.J., LIU B., Ren M.C., GE X.P., Xie J., Cui H.H. Effects of dietary arginine level on growth performance, free essential amino acids, hematological characteristics, and immune response in juvenile blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala) J Fish Sci China. 2014;21:549–559. [Google Scholar]

- Lin H.Z., Tan X.H., Zhou C.P., Niu J., Xia D.M., Huang Z. Effect of dietary arginine levels on the growth performance, feed utilization, non-specific immune response and disease resistance of juvenile golden pompano Trachinotus ovatus. Aquaculture. 2015;437:382–389. [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z., Liu Y.J., Mai K.S., Tian L.X. Advance in researches on arginine requirement for fish: a review. J Fish China. 2004;28:450–459. [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z., Liu Y.J., Mai K.S., Tian L.X., Tan X.Y., Yang H.J. Effects of dietary arginine levels on growth performance and body composition of juvenile grouper Epinephelus coioides. J Appl Ichthyol. 2007;23:252–257. [Google Scholar]

- Niu F.C., Huang Y.H., Cao J.M., Wang G.X., Zhao H.X., Sun Y.P. Effect of five additives on growth performance, body composition and serum biochemical indices of yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco) Chin J Anim Nutr. 2015;27:2176–2183. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NRC . National Academy Press; Washington: 2011. Nutrient requirements of fish and shrimp; pp. 57–92. [Google Scholar]

- Oehme M., Grammes F., Takle H., Zambonino-Infante J.L., Refstie S.,S., Thomassen M. Dietary supplementation of glutamate and arginine to Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) increases growth during the first autumn in sea. Aquaculture. 2010;310:156–163. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen R.E., Sundell K.,M., Mayhew T., Myklebust R., Ringø E. Acute stress alters intestinal function of rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum) Aquaculture. 2005;250:480–495. [Google Scholar]

- Pan J.L., Ding S.Y., Ge J.C., Yan W.H., Hao C., Chen J.X. Development of cryopreservation for maintaining yellow catfish Pelteobagrus fulvidraco sperm. Aquaculture. 2008;279:173–176. [Google Scholar]

- Pohlenz C., Buentello A., Helland S., Gatlin D.M., III Effects of dietary arginine supplementation on growth, protein optimization and innate immune response of channel catfish Ictalurus punctatus (Rafinesque 1818) Aquac Res. 2014;45:491–500. [Google Scholar]

- Rahimnejad S., Lee K.J. Dietary arginine requirement of juvenile red sea bream Pagrus major. Aquaculture. 2014;434:418–424. [Google Scholar]

- Ren M.C., Liao Y.J., Xie J., Liu B., Zhou Q.L., Ge X.P. Dietary arginine requirement of juvenile blunt snout bream, Megalobrama amblycephala. Aquaculture. 2013;414–415:229–234. [Google Scholar]

- Ren M.C., Ai Q.H., Mai K.S. Dietary arginine requirement of juvenile cobia (Rachycentron canadum) Aquac Res. 2014;45:225–233. [Google Scholar]

- Shi G.C., Dong X.H., Chen G., Tan B.P. Effects of dietary lipid level on growth performance of genetic improvement of farmed tilapia (GIFT, Oreochromis niloticus) and its serum biochemical indices and fatty acid composition under cold stress. Chin J Anim Nutr. 2012;24:2154–2164. [Google Scholar]

- Shi Z.H., Zhang Y.L., Gao Q.X., Peng S.M., Zhang C.J. Dietary vitamin E level affects the response of juvenile Epinehelus moara to ammonia nitrogen stress. Chin J Anim Nutr. 2015;27:1596–1604. [Google Scholar]

- Sun H.N., Yang H.M., Wang Z.Y., Zhang D.C., Zhang F.F., Yang Z. Nutrition physiological and immune functions of arginine in animals. Chin J Anim Nutr. 2014;26:54–62. [Google Scholar]

- Tu Y.Q., Xie S.Q., Han D., Yang Y.X., Jin J.Y., Zhu X.M. Dietary arginine requirement for gibel carp (Carassis auratus gibelio var. CAS III) reduces with fish size from 50g to 150g associated with modulation of genes involved in TOR signaling pathway. Aquaculture. 2015;449:37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wan J.L., Mai K.S., AI Q.H. The recent advance on arginine nutritional physiology in fish. J Fish Sci China. 2006;13:679–685. [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Liu Y., Feng L., Jiang W.D., Kuang S.Y., Jiang J. Effects of dietary arginine supplementation on growth performance, flesh quality, muscle antioxidant capacity and antioxidant-related signalling molecule expression in young grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) Food Chem. 2015;167:91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.06.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue F., Pan L.Q., Xie P., Zheng D.B., Li J. Immune responses and expression of immune-related genes in swimming crab Portunus trituberculatus exposed to elevated ambient ammonia-N stress. Comp Biochem Physiol Part A Mol Integr Physiol. 2010;157:246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Y.R., Zou Z.Y., Zhu J.L., Li D.Y., Xiao W., Han J. Effects of dietary arginine on growth performance, feed utilization, haematological parameters and non-specific immune responses of juvenile Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus L.) Aquac Res. 2013:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.X., Sun S.M., Ge X.P., Zhu J., LI B., Miao L.H. Acute effects of ammonia exposure on histopathology of gill, liver and kidney in juvenile Megalobrama amblycephala and the post-exposure recovery. J Fish China. 2015;39:233–244. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H.X., Cao J.M., Huang Y.H., Zhou C.P., Wang G.X., Mo W.Y. Effects of dietary nucleotides on growth, physiological parameters and antioxidant responses of Juvenile Yellow Catfish Pelteobagrus fulvidraco. Aquac Res. 2015:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F., Xiong W., Xiao J.X., Shao Q.J., Bergo O.N., Hua Y. Optimum arginine requirement of juvenile black sea bream, Sparus macrocephalus. Aquac Res. 2010;41:e418–e430. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H., Chen N., Qiu X., Zhao M., Jin L. Arginine requirement and effect of arginine intake on immunity in largemouth bass, Micropterus salmoides. Aquac Nutr. 2012;18:107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q.C., Zeng W.P., Wang H.L., Xie F.J., Wang T., Zheng C.Q. Dietary arginine requirement of juvenile yellow grouper Epinephelus awoara. Aquaculture. 2012;350–353:175–182. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q.C., Jin M., Elmada Z.C., Liang X.P., Mai K.S. Growth, immune response and resistance to Aeromonas hydrophila of juvenile yellow catfish, Pelteobagrus fulvidraco, fed diets with different arginine levels. Aquaculture. 2015;437:84–91. [Google Scholar]