Abstract

Growth and health responses of pigs fed fermented liquid diet are not always consistent and causes for this issue are still not very clear. Metabolites produced at different fermentation time points should be one of the most important contributors. However, currently no literatures about differential metabolites of fermented liquid diet are reported. The aim of this experiment was to explore the difference of metabolites in a fermented liquid diet between different fermentation time intervals. A total of eighteen samples that collected from Bacillus subtilis fermented liquid diet on days 7, 21 and 35 respectively were used for the identification of metabolites by gas chromatography time of flight mass spectrometry (GC-TOF-MS). Fifteen differential metabolites including melibiose, sortitol, ribose, cellobiose, maltotriose, sorbose, isomaltose, maltose, fructose, d-glycerol-1-phosphate, 4-aminobutyric acid, beta-alanine, tyrosine, pyruvic acid and pantothenic acid were identified between 7-d samples and 21-d samples. The relative level of melibiose, ribose, maltotriose, d-glycerol-1-phosphate, tyrosine and pyruvic acid in samples collected on day 21 was significantly higher than that in samples collected on day 7 (P < 0.01), respectively. Eight differential metabolites including ribose, sorbose, galactinol, cellobiose, pyruvic acid, galactonic acid, pantothenic acid and guanosine were found between 21-d samples and 35-d samples. Samples collected on day 35 had a higher relative level of ribose than that in samples collected on day 21 (P < 0.01). In conclusion, many differential metabolites which have important effects on the growth and health of pigs are identified and findings contribute to explain the difference in feeding response of fermented liquid diet.

Keywords: Bacillus subtilis, Fermented liquid diet, Differential metabolites, GC-TOF-MS

1. Introduction

Supplementation of probiotics in an adequate amount to human or animals has health-promoting benefits to the host, because many bioactive metabolites including functional oligosaccharides (Sriphannam et al., 2012), organic acids (Gao et al., 2012), antimicrobial peptides (Majumdar and Bose, 1958, Thasana et al., 2010), vitamins (Burgess et al., 2009) and digestive enzymes (Kim et al., 2007, Romero-Garcia et al., 2009) are produced by probiotics during fermentation, and these metabolites together with probiotcs have important roles in terms of rebalance of microbiota and osmotic pressure in intestine (Franks, 2011), improvement of nutrients digestion and absorption (Kim et al., 2007), anti-stress (Mills et al., 2011), and prevention of obesity (Raoult, 2009, Angelakis et al., 2013), diabetes mellitus (Elliott et al., 2002), hypertension (Ebel et al., 2014) and other intestinal disorders (Caffarelli and Bernasconi, 2007, Weizman, 2010, Fukumoto et al., 2014). However, improper use of probiotics or its fermentation product might result in undesired effects. For example, lactobacillus is often used to prevent animals from diarrhoea, but an experiment reported that oral administration of high-dose Lactobacillus rhamnosus to piglets increased the severity of diarrhoea (Li et al., 2012). Bacillus genus is also one of the best probiotics for the controlling of diarrhoea (Kantas et al., 2015), but our feeding experiment showed that feeding of Bacillus subtilis-fermented liquid diet to suckling and early weaned piglets caused severe diarrhoea. The specific factors for the diarrhoea caused by the feeding of high dose probiotics or probiotics-fermented diet need to be further clarified.

In this study, gas chromatography time of flight mass spectrometry (GC-TOF-MS) was performed to detect metabolites that produced in B. subtilis fermented liquid diet at different fermentation times and to figure out what was the difference in metabolites between different fermentation intervals.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Fermented liquid diet preparation and sampling

Basal diet was prepared with the ingredients that listed in Table 1. After preparation, 500 g basal diet and 1,100 g tape water were placed into each polypropylene bag with a total of 25 bags, all bags were sealed with heat-sealer and heated in a container with steam at 80°C for 30 min under normal pressure to kill some undesirable microbes, then taken out and placed in a room (indoor temperature:22.5–33.9°C) for fermentation. Six bags of fermented liquid diet were randomly selected and sampled in different times of shelf life (samples collected from day 7 were named as T7; samples collected from day 21 were named as T21; samples collected from day 35 were named as T35). Sample collected from each bag was placed into a 10 mL sterile plastic tube and immediately stored at −80°C for metabolomics study.

Table 1.

Ingredients and nutrient levels of the basal diet (air-dry basis).

| Item | Content |

|---|---|

| Ingredient, % | |

| Corn | 51.0 |

| Wheat bran | 7.0 |

| Extruded soybean | 30.0 |

| Fishmeal (Peru) | 3.0 |

| Lactose | 2.0 |

| Sucrose | 3.0 |

| Premix1 | 4.0 |

| Total | 100.0 |

| Nutrient levels2, % | |

| Digestible energy, MJ/kg | 13.71 |

| Crude protein | 19.67 |

| Calcium | 1.05 |

| Total phosphorus | 0.66 |

| Lysine | 1.32 |

| Methionine + Cystine | 0.78 |

Premix provided per kilogram diet: VA 450,000 IU, VD3 72,000 IU, VE 2,750 IU, VK3 100 mg, VB1 90 mg, VB2 280 mg, VB6 190 mg, VB12 0.8 mg, niacin 1,450 mg, pantothenic acid 950 mg, biotin 3 mg, choline chloride 10,500 mg, lysine 40,000 mg, Cu 3,750 mg, Zn 2,750 mg, Fe 2,500 mg, Mn 2,000 mg, I 30 mg, Co 38 mg, Se 10.5 mg, Ca 137,000 mg, P 40,800 mg, NaCl 80,000 mg, and Wole200 (heat-resistant Bacillus subtilis HEWD113, effective live bacteria ≥2 × 1010 CFU/g) 7,500 mg.

Nutrient levels in the table were analyzed value except digestible energy.

2.2. Metabolites extraction, derivatization and detection

One hundred milligram sample, 0.4 mL methanol-chloroform (vol:vol = 3:1) and 20 μL ribitol (0.2 mg/mL stock in dH2O) were mixed in 2 mL EP tube by vortexing and extracted for 5 min. After that, EP tube was centrifuged for 15 min at 4°C with a speed of 2,410 × g, 0.40 mL supernatant was removed from EP tube and pipetted into a 2 mL glass vial. Glass vial with supernatant was dried in vacuum concentrator at 30°C for 1.5 h, after that, 80 μL methoxymethyl amine salt (dissolved in pyridine, final concentration of 20 mg/mL) was added into the glass vial. Sealed, mixed and incubated glass vial at 37°C for 2 h in an oven, then added 100 μL Bis (trimethylsilyl) trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA, containing 1% tetrachloro-4-methylsulfonyl, vol/vol) into vial, sealed the vial again and incubated it at 70°C for 1 h. Later, added 10 μL fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) to the glass vial, and mixed it again for GC-TOF-MS analysis. The GC-TOF-MS analysis was performed using an Agilent 7890 gas chromatograph system coupled with a Pegasus HT time-of-flight mass spectrometer. The system utilized a DB-5MS capillary column coated with 5% diphenyl cross-linked with 95% dimethylpolysiloxane (30 m × 250 μm inner diameter, 0.25 μm film thickness; J&W Scientific, Folsom, CA, USA). Aliquot (1 μL) of the analyte was injected in the splitless mode. Helium was used as the carrier gas, the front inlet purge flow was 3 mL per minute, and the gas flow rate through the column was 20 mL per minute. The initial temperature was kept at 50°C for 1 min, then raised to 330°C at a rate of 10°C per minute, then kept for 5 min at 330°C. The injection, transfer line, and ion source temperatures were 280, 280, and 220°C, respectively. The energy was −70 eV in electron impact mode. The mass spectrometry data were acquired in full-scan mode with the m/z range of 85–600 at a rate of 20 spectra per second after a solvent delay of 366 s.

2.3. Data analysis

Chroma TOF 4.3X software of LECO Corporation and LECO-Fiehn Rtx5 database were used for raw peaks exacting, the data baselines filtering and calibration of the baseline, peak alignment, deconvolution analysis, peak identification and integration of the peak area (Kind et al., 2009). SIMCA-P+ software (V13.0,Umetrics AB, Umea, Sweden) was run for principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA), peaks with similarity greater than 700, variable importance projection (VIP) exceeding 1.0 and P < 0.05 by T-test were selected as the reliable different metabolites.

3. Results

3.1. Metabolites detection and identification

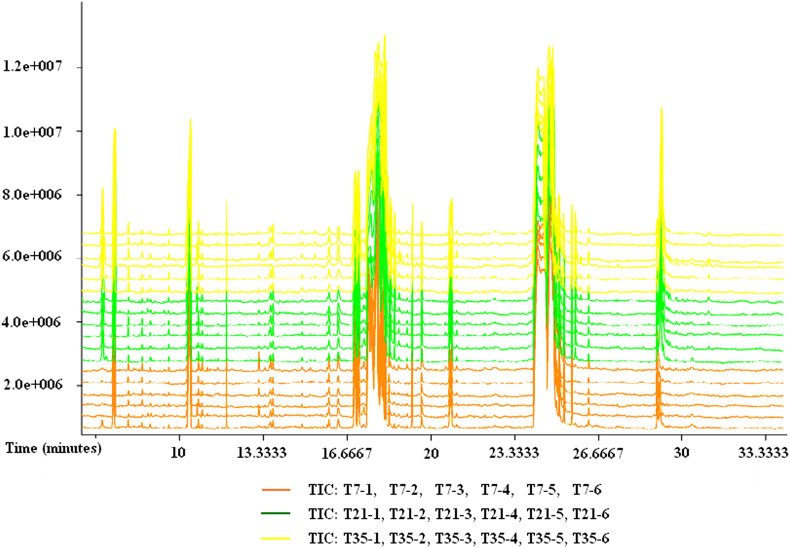

Total ion chromatograms (TIC) of fermented liquid diet samples collected on days 7, 21 and 35 were shown in Fig. 1. A total of 476 raw peaks were detected by GC-TOF-MS and identified with LECO-Fiehn Rtx5 database in 18 samples. After processed by numerical simulation, noise filtering and data standardization, and 439 valid peaks were used for later metabolomics analysis.

Fig. 1.

TIC chromatograms of GC-TOF-MS for fermented liquid diet at different fermentation durations. TIC: total ion chromatogram; T7: samples of fermented liquid diet collected at day 7; T7-1 to T7-6: numbers of samples collected at day 7; T21: samples of fermented liquid diet collected at day 21; T21-1 to T21-6: numbers of samples collected at day 21; T35: samples of fermented liquid diet collected at day 35; T35-1 to T35-6: numbers of samples collected at day 35.

3.2. Results of PCA and OPLS-DA

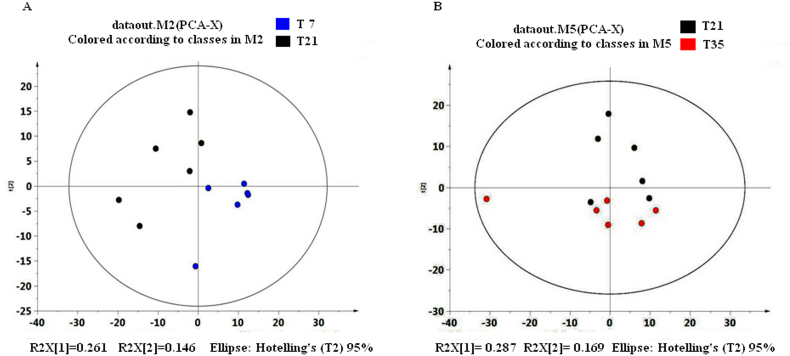

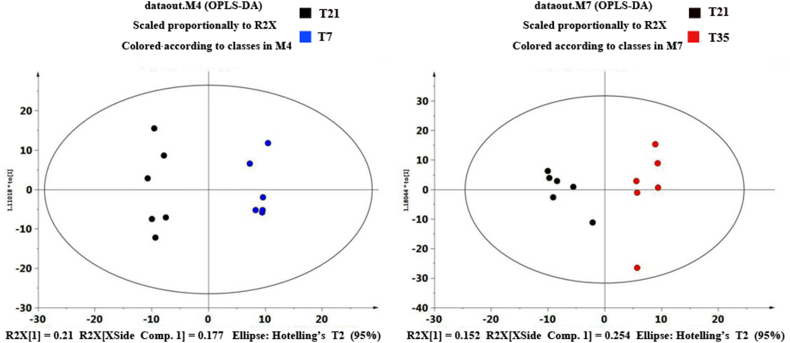

All samples were within the 95% Hotelling T2 ellipse, there was a good separation in peak clusters between T7 and T21 samples and the 2 principal components explained 40.7% of the total variances (Fig. 2A). No clear partition in peak clusters between T21 and T35 samples and the first and second principal components explained 45.6% of the total variances (Fig. 2B). Peak clusters between T7 and T21 samples or between T21 and T35 samples were clearly discriminated when processed them with OPLS-DA model (Fig. 3A, B), the R2Y for T7-T21 group and T21-T35 group was 0.986 and 0.909, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Principal component analysis of Bacillus subtilis-fermented liquid diet at different fermentation times. PCA: principal component analysis; T7: samples of fermented liquid diet collected at day 7; T21: samples of fermented liquid diet collected at day 21; T35: samples of fermented liquid diet collected at day 35; M: map; R2X: explanatory variables of the model.

Fig. 3.

OPLS-DA score plots of samples collected from different fermentation time points. OPLS-DA: orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis; T7: samples of fermented liquid diet collected at day 7; T21: samples of fermented liquid diet collected at day 21; T35: samples of fermented liquid diet collected at day 35; M: map; R2X: explanatory variables of the model.

3.3. Screening of reliable differential metabolites

Fifteen reliable differential metabolites were screened out between T7 group and T21 group (Table 2) including 10 carbohydrates and carbohydrate conjugates, 3 amino acids and analogues, 1 organic acid and derivative and 1 aliphatic acyclic compound. Compared with T7 group, the relative level of these differential metabolites in T21 group increased (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01) with the exception of cellobiose, maltose, fructose and beta-alanine. Eight reliable differential metabolites were identified including 5 carbohydrates and carbohydrate conjugates, 1 organic acid and derivative, 1 aliphatic acyclic compound and 1 nucleotide and analogue when compared fermented liquid diet in T21 group with fermented liquid diet in T35 group (Table 3), the relative level of sorbose, galactinol, cellobiose, pyruvic acid, galactonic acid and pantothenic acid decreased (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01) and the relative level of ribose and guanosine increased (P < 0.01). The reliable differential metabolites shared by T7, T21 and T35 groups were ribose, cellobiose, sorbose, pyruvic acid and pantothenic acid, the relative level of ribose increased (P < 0.01) but the relative level of cellobiose decreased (P < 0.05) when fermented liquid diet from days 7–35. The relative level of reliable differential metabolites in fermented liquid diet ranked as follows, T7: 4-aminobutyric acid > maltose > fructose > tyrosine > d-glycerol-1-phosphate > cellobiose > ribose > sorbitol > beta-alanine > melibiose > pantothenic acid > pyruvic acid > maltotriose = isomaltose = sorbose, T21: 4-aminobutyric acid > tyrosine > maltose > d-glycerol -1-phosphate > melibiose > ribose > cellobiose > sorbose > sorbitol > pyruvic acid > pantothenic acid > maltotriose > beta-alanine > isomaltose > fructose, T35: ribose > guanosine > galactonic acid > pyruvic acid > pantothenic acid > galactinol > cellobiose > sorbose. The pathways concerned were carbohydrate digestion and absorption, protein and amino acid metabolism, vitamin B metabolism, ABC transporters, alkaloids biosynthesis, glycerolipid and glycerophospholipid metabolism, bacterial chemotaxis, insulin secretion and type Ⅱ diabetes mellitus.

Table 2.

Results of reliable differential metabolites identified from fermented liquid diet between T7 and T21.

| Metabolites | R.T. | Mass | T71 | T212 | VIP | P-value3 | Fold change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melibiose | 25.77 | 160 | 0.0545 | 0.3776 | 1.97 | 0.00 | 0.14 |

| Sorbitol | 18.21 | 345 | 0.0847 | 0.1043 | 1.39 | 0.04 | 0.81 |

| Ribose | 15.37 | 103 | 0.1062 | 0.3578 | 1.99 | 0.00 | 0.30 |

| Cellobiose | 24.89 | 235 | 0.3077 | 0.2759 | 1.53 | 0.03 | 1.16 |

| Maltotriose | 31.36 | 204 | 0.0001 | 0.0538 | 2.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Isomaltose | 26.05 | 160 | 0.0001 | 0.0059 | 1.51 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Maltose | 25.29 | 204 | 1.5253 | 0.9369 | 1.38 | 0.03 | 1.63 |

| Fructose | 17.66 | 262 | 1.3695 | 0.0001 | 1.83 | 0.01 | 13,695.00 |

| Sorbose | 17.56 | 235 | 0.0001 | 0.1401 | 1.46 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| D-glycerol -1-phosphate | 16.32 | 299 | 0.6394 | 0.8895 | 1.77 | 0.00 | 0.72 |

| 4-aminobutyric acid | 13.71 | 174 | 1.6141 | 1.8736 | 1.40 | 0.03 | 0.86 |

| Beta-alanine | 12.42 | 86 | 0.0575 | 0.0310 | 1.31 | 0.04 | 1.85 |

| Tyrosine | 18.26 | 218 | 0.8436 | 1.5437 | 1.95 | 0.00 | 0.55 |

| Pyruvic acid | 7.22 | 174 | 0.0384 | 0.0781 | 1.89 | 0.00 | 0.49 |

| Pantothenic acid | 18.71 | 291 | 0.0432 | 0.0595 | 1.49 | 0.03 | 0.73 |

R.T. = retention time; VIP = variable importance projection.

Samples of fermented liquid diet collected at day 7.

Samples of fermented liquid diet collected at day 21.

P < 0.05 means the difference in concentration of metabolites between T7 and T21 was significant, P < 0.01 means the difference in concentration of metabolites between T7 and T21 was extremely significant.

Table 3.

Results of reliable differential metabolites identified from fermented liquid diet between T21 and T35.

| Metabolites | R.T. | Mass | T211 | T352 | VIP | P-value3 | Fold change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ribose | 15.37 | 103 | 0.3578 | 1.0126 | 2.55 | 0.00 | 0.35 |

| Sorbose | 17.56 | 235 | 0.1401 | 0.0001 | 1.83 | 0.04 | 1,401.00 |

| Galactinol | 26.45 | 204 | 0.0361 | 0.0212 | 1.67 | 0.04 | 1.70 |

| Cellobiose | 24.85 | 390 | 0.2759 | 0.0052 | 1.91 | 0.03 | 53.06 |

| Pyruvic acid | 7.22 | 174 | 0.0781 | 0.0420 | 1.97 | 0.01 | 1.86 |

| Galactonic acid | 18.73 | 292 | 0.2000 | 0.1128 | 1.86 | 0.02 | 1.77 |

| Pantothenic acid | 18.71 | 291 | 0.0595 | 0.0349 | 1.82 | 0.02 | 1.70 |

| Guanosine | 25.17 | 324 | 0.1380 | 0.2387 | 1.99 | 0.01 | 0.58 |

R.T. = retention time; VIP = variable importance projection.

Samples of fermented liquid diet collected at day 21.

Samples of fermented liquid diet collected at day 35.

P < 0.05 means the difference in concentration of metabolites between T21 and T35 was significant, P < 0.01 means the difference in concentration of metabolites between T21 and T35 was extremely significant.

4. Discussion

Health benefits of fermented foods result from the interaction of live Lactobacillus or (and) Bacillus strains with host and the ingestion of functional metabolites (vitamins, bioactive peptides, organic acids, and fatty acids et al.) produced by probiotics fermentation (Stanton et al., 2005). It was reported that consumption of Bifidobacterium lactis LKM512-fermented yogurt increased fecal spermidine levels and significantly reduced the mutagenicity level (Matsumoto and Benno, 2004) When fermented soybean with Bacillus strains (Licheniformis KCCM 11053P, Licheniformis 58, and Amyloliquefaciens CH86-1). Many beneficial metabolites for health including ribose, alanine, fructose, maltose, melibiose, and sorbitol have been identified, and these metabolites have effects in the improvement of intestinal health and immune response (Baek et al., 2010, Kim et al., 2012).

B. subtilis is a heat-resistant gram positive bacterium and is recognized as a safe microorganism by the Food and Drug Administration (Romero-Garcia et al., 2009). It can secrete enzymes to degrade carbohydrate and protein into mono-and oligo-saccharides, organic acids and amino acids (Valasaki et al., 2008). The GC-TOF-MS results showed that carbohydrates and proteins in the B. subtilis-supplemented liquid diet had been partly converted into melibiose, sorbitol, ribose, cellobiose, sorbose, maltose, fructose, alanine, tyrosine, pyruvic acid and pantothenic acid. These metabolites can be used either as substrates for the growth of microbes in the fermented liquid diet or as bioactive materials in host gut to manage animal's health in terms of enteric, cardiovascular and respiratory system.

Extruded soybean or soybean meal generally contains raffinose at a level of 1.0%–2.2% and it often causes monogastric animals to flatulence and diarrhea. In general, the diet for suckling and early weaned piglets consists of high proportion of extruded soybean or soybean meal, when piglets ingest this kind of diet, piglets often suffer from a mild to severe diarrhea. How to decrease the level of raffinose in the diet with high proportion of extruded soyabean or soyabean meal is very important for the improvement of enteric health of monogastric animals. Raffinose can be converted into melibiose by B. subtilis B7 and B15 (Ouoba et al., 2007), data in Table 2 showed that the level of melibiose in the fermented liquid diet increased progressively to a relative constant level as fermentation time advanced, this implied that raffinose in the fermented liquid diet can also be effectively converted into melibiose by B. subtilis HEWD113 fermentation. The reason for the relative level of melibiose at day 21 was significantly higher than that at day 7 was probably that B. subtilis HEWD113 grew in its exponential growth phase from day 7 to day 21, so the ability of producing melibiose by B. subtilis HEWD113 increased progressively. After day 21, B. subtilis HEWD113 grew in its stationary or death phase and the relative level of melibiose had no significant difference when compared day 21 to day 35. Melibiose is a functional oligosaccharide, it can increase the amount of lactic bacteria in enteric tract and improve stool condition (Boucher et al., 2002).

Some strains of Zymomonas, Candida and Lactobacillus genus can convert lactose, glucose, fructose and maltose into sorbitol (Silveira and Jonas, 2002, Ladero et al., 2007) and sorbitol can be oxidized into sorbose during fermentation (Xu et al., 2014). In the present study, B. subtilis HEWD113 grew in its exponential growth phase from day 7 to day 21, many kinds of enzymes were secreted by B. subtilis HEWD113, therefore, a large number of mono-and di-saccharides were produced and used to produce sorbitol, this resulted in a significantly higher relative level of sorbitol in samples from T21 group when compared with samples from T7 group. During exponential growth phase, the relative level of sorbitol increased and sorbose could be produced by sorbitol oxidization, this should be the reason why the relative level of sorbose increased significantly. After day 21, B. subtilis HEWD113 grew in its stationary or death phase, insufficient sorbitol and sorbose fermentation in this phase resulted in a very low relative level of sorbose on day 35. Sorbitol was used as an osmotic laxative material for constipation treatment (Di Saverio et al., 2009), but when ingested in large amounts (30–50 g), it led to abdominal pain, bloating problems and mild to severe diarrhoea owing to intestinal malabsorption and increased colonic osmolarity (Islam and Sakaguchi, 2006), especially on an empty stomach, sorbitol sped up transit time and increased stool output (Livesey, 2001). Sorbose is one of the poorly digestible sugars, feeding sorbose to animals decreased body weight, liver and abdominal fat weights by suppressing feed intake (Furuse et al., 1991, Oku et al., 2014). Liquid diet fermented with B. subtilis from day 7 to day 21 was high in the levels of sorbitol and sorbose, this should be the contributor to the diarhhoea of suckling and early weaned piglets.

Ribose can be biosynthesized by B. subtilis with lots of carbon sources (glucose, sorbitol et al.) (Park et al., 2006). Carbon sources such as glucose and sorbitol were abundant in this fermented liquid diet, because corn starch, sucrose and lactose in the fermented liquid diet could be converted constantly into glucose by enzymes that secreted by B. subtilis HEWD113, this could increase the level of ribose in fermented liquid diet constantly from day 7 to day 35. Ribose has key roles in energetic metabolism and glycogen synthesis, it can be rapidly metabolized to glucose in the liver via the pentose phosphate to improve adenosine-triphosphate (ATP) production and reduce soreness and fatigue caused by exercise (Peveler et al., 2006).

On the contrary to ribose, the level of cellobiose, maltose and fructose decreased progressively as fermentation advanced, it is probably caused by B. subtilis growth, because cellobiose, maltose and fructose are often used as the favorable substrates for the growth of B. subtilis (Romero-Garcia et al., 2009, Quigley, 2012). In addition, cellobiose, maltose and fructose can be converted into glucose and products of sugar metabolism, glucose can be used to produce lactic acid or lactate by fermentation to lower the pH of fermented liquid diet, this also resulted in a decrease in level of cellobiose, maltose and fructose from day 7 to day 35. It was reported that cellobiose has effect in reducing serum lipid concentration (Hetzler and Steinbüchel, 2013). Maltose can be taken up by B. subtilis through ATP binding cassette (ABC) and serve as sole carbon and energy sources for B. subtilis growth (Schonert et al., 2006). Fructose is a palatable monosaccharide and when poorly absorbed, it can cause diarrhoea or bloating (McGuinness and Cherington, 2003), this is also probably the cause for the diarrhoea of suckling and early weaned piglets when fed B. subtilis fermented liquid diet to these piglets, because liquid diet fermented with B. subtilis from day 7 to day 21 had high levels of fructose.

Pyruvic acid can be produced by lactic acid bacteria using carbohydrates, organic acids or amino acids as substrates (Liu, 2003). The relative level of pyruvic acid increased significantly from day 7 to day 21 and then decreased significantly from day 21 to day 35, this could be caused by the sufficient substrates for pyruvic acid synthesis during its exponential growth phase of B. subtilis HEWD113, insufficient materials for the production of pyruvic acid during stationary or death phase and the metabolism of pyruvic acid would lower the relative level of pyruvic acid.

Pantothenic acid could be produced by microbial fermentation (Baigori et al., 1991) and in this study, the relative level of pantothenic acid firstly increased from day 7 to day 21 and then decreased from day 21 to day 35, this also demonstrated that B. subtilis HEWD113 grew in its exponential growth phase from day 7 to day 21 and then grew in its stationary or death phase from day 21 and day 35.

5. Conclusions

Differential metabolites and their relative levels varied with fermentation duration, and sugar metabolites were the main differential metabolites in the B. subtilis-fermented liquid diet and the reliable differential metabolites shared by B. subtilis-fermented liquid diet on days 7, 21 and 35 were ribose, cellobiose, sorbose, pyruvic acid and pantothenic acid. Control of fermentation duration is one of the major measures to produce the desired metabolites when ferment carbohydrate-fortified liquid diet with B. subtilis, and these findings can help people better understand the difference in feeding response of fermented liquid diet.

Acknowledgement

The study was supported by Jiangxi Provincial Key Technology R&D Program (20121BBF60032 and 20132BBF60039).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

Contributor Information

Wei Lu, Email: lw20030508@163.com.

Huadong Wu, Email: whd0618@163.com.

References

- Angelakis E., Merhej V., Raoult D. Related actions of probiotics and antibiotics on gut microbiota and weight modification. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:889–899. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70179-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek J.G., Shim S.M., Kwon D.Y., Choi H.K., Lee C.H., Kim Y.S. Metabolite profiling of Cheonggukjang, a fermented soybean paste, inoculated with various Bacillus strains during fermentation. Biosci Biotech Bioch. 2010;74:1860–1868. doi: 10.1271/bbb.100269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baigori M., Grau R., Morbidoni H.R., de Mendoza D. Isolation and characterization of Bacillus subtilis mutants blocked in the synthesis of pantothenic acid. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4240–4242. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.13.4240-4242.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher I., Parrot M., Gaudreau H., Champagne C.P., Vadeboncoeur C., Moineau S. Novel food-grade plasmid vector based on melibiose fermentation for the genetic engineering of Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microb. 2002;68:6152–6161. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.12.6152-6161.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess C.M., Smid E.J., van Sinderen D. Bacterial vitamin B2, B11 and B12 overproduction: an overview. Int J Food Microbio. 2009;133:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffarelli C., Bernasconi S. Preventing necrotising enterocolitis with probiotics. Lancet. 2007;369:1578–1580. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60721-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Saverio S., Tugnoli G., Orlandi P.E., Casali M., Catena F., Biscardi A. A 73-year-old man with long-term immobility presenting with abdominal pain. PLOS Med. 2009;6:e1000092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebel B., Lemetais G., Beney L., Cachon R., Sokol H., Langella P. Impact of probiotics on risk factors for cardiovascular diseases. A review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2014;54:175–189. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2011.579361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott S.S., Keim N.L., Stern J.S., Teff K., Havel P.J. Fructose, weight gain, and the insulin resistance syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:911–922. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.5.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks I. Probiotics: probiotics and diarrhea in children. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:602. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto S., Toshimitsu T., Matsuoka S., Maruyama A., Oh-Oka K., Takamura T. Identification of a probiotic bacteria-derived activator of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor that inhibits colitis. Immunol Cell Biol. 2014;92:460–465. doi: 10.1038/icb.2014.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuse M., Ishii T., Miyagawa S., Nakagawa J., Shimizu T., Watanabe T. Effect of dietary sorbose on lipid metabolism in male and female broilers. Poult Sci. 1991;70:95–102. doi: 10.3382/ps.0700095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao T., Wong Y., Ng C., Ho K. L-lactic acid production by Bacillus subtilis MUR1. Bioresour Technol. 2012;121:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.06.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetzler S., Steinbüchel A. Establishment of cellobiose utilization for lipid production in Rhodococcus opacus PD630. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:3122–3125. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03678-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam M.S., Sakaguchi E. Sorbitol-based osmotic diarrhea: possible causes and mechanism of prevention investigated in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7635–7641. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i47.7635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantas D., Papatsiros V.G., Tassis P.D., Giavasis I., Bouki P., Tzika E.D. A feed additive containing Bacillus toyonensis (Toyocerin(®)) protects against enteric pathogens in postweaning piglets. J Appl Microbiol. 2015;118:727–738. doi: 10.1111/jam.12729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E.Y., Kim Y.H., Rhee M.H., Song J.C., Lee K.W., Kim K.S. Selection of Lactobacillus sp. PSC101 that produces active dietary enzymes such as amylase, lipase, phytase and protease in pigs. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 2007;53:111–117. doi: 10.2323/jgam.53.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.Y., Choi J.N., John K.M.M., Kusano M., Oikawa A., Saito K. GC-TOF-MS- and CE-TOF-MS-based metabolic profiling of cheonggukjang (fast-fermented bean paste) during fermentation and its correlation with metabolic pathways. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:9746–9753. doi: 10.1021/jf302833y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kind T., Wohlgemuth G., Lee do Y., Lu Y., Palazoglu M., Shahbaz S. FiehnLib – mass spectral and retention index libraries for metabolomics based on quadrupole and time-of-flight gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2009;81:10038–10048. doi: 10.1021/ac9019522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladero V., Ramos A., Wiersma A., Goffin P., Schanck A., Kleerebezem M. High-level production of the low-calorie sugar sorbitol by Lactobacillus plantarum through metabolic engineering. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:1864–1872. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02304-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.Q., Zhu Y.H., Zhang H.F., Yue Y., Cai Z.X., Lu Q.P. Risks associated with high-dose Lactobacillus rhamnosus in an Escherichia coli model of piglet diarrhoea: intestinal microbiota and immune imbalances. PLOS One. 2012;7:e40666. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.Q. Practical implications of lactate and pyruvate metabolism by lactic acid bacteria in food and beverage fermentations. Int J Food Microbiol. 2003;83:115–131. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(02)00366-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livesey G. Tolerance of low-digestible carbohydrates: a general view. Br J Nutr. 2001;85:S7–S16. doi: 10.1079/bjn2000257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar S.K., Bose S.K. Mycobacillin, a new anti-fungal antibiotic produced by B. subtilis. Nature. 1958;181:134–135. doi: 10.1038/181134a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M., Benno Y. Consumption of Bifidobacterium lactis LKM512 yogurt reduces gut mutagenicity by increasing gut polyamine contents in healthy adult subjects. Mutat Res. 2004;568:147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness O.P., Cherington A.D. Effects of fructose on hepatic glucose metabolism. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2003;6:441–448. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000078990.96795.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills S., Stanton C., Fitzgerald G.F., Ross R.P. Enhancing the stress responses of probiotics for a lifestyle from gut to product and back again. Microb Cell Fact. 2011;10:S19. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-10-S1-S19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oku T., Murata-Takenoshita Y., Yamazaki Y., Shimura F., Nakamura S. D-Sorbose inhibits disaccharidase activity and demonstrates suppressive action on postprandial blood levels of glucose and insulin in the rat. Nutr Res. 2014;34:961–967. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouoba L.I.I., Diawara B., Christensen T., Mikkelsen J.D., Jakobsen M. Degradation of polysaccharides and non-digestible oligosaccharides by Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus pumilus isolated from Soumbala, a fermented African locust bean (Parkia biglobosa) food Condiment. Eur Food Res Technol. 2007;224:689–694. [Google Scholar]

- Park Y.C., Choi J.H., Bennett G.N., Seo J.H. Characterization of D-ribose biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis JY200 deficient in transketolase gene. J Biotechnol. 2006;121:508–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peveler W.W., Bishop P.A., Whitehorn E.J. Effects of ribose as an ergogenic aid. J Strength Cond Res. 2006;20:519–522. doi: 10.1519/17355.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley E.M.M. Prebiotics and probiotics: their role in the management of gastrointestinal disorders in adults. Nutr Clin Pract. 2012;27:195–200. doi: 10.1177/0884533611423926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raoult D. Probiotics and obesity: a link? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:616. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Garcia S., Hernández-Bustos C., Merino E., Gosset G., Martinez A. Homolactic fermentation from glucose and cellobiose using Bacillus subtilis. Microb Cell Fact. 2009;8:23. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-8-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonert S., Seitz S., Krafft H., Feuerbaum E.A., Andernach I., Witz G. Maltose and maltodextrin utilization by Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:3911–3922. doi: 10.1128/JB.00213-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira M.M., Jonas R. The biotechnological production of sorbitol. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;59:400–408. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriphannam W., Lumyong S., Niumsap P., Ashida H., Yamamoto K., Khanongnuch C. A selected probiotic strain of lactobacillus fermentum CM33 isolated from breast-fed infants as a potential source of β-galactosidase for prebiotic oligosaccharide synthesis. J Microbiol. 2012;50:119–126. doi: 10.1007/s12275-012-1108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton C., Ross R.P., Fitzgerald G.F., Van Sinderen D. Fermented functional foods based on probiotics and their biogenic metabolites. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2005;16:198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thasana N., Prapagdee B., Rangkadilok N., Sallabhan R., Aye S.L., Ruchirawat S. Bacillus subtilis SSE4 produces subtulene A, a new lipopeptide antibiotic possessing an unusual C15 unsaturated beta-amino acid. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:3209–3214. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valasaki K., Staikou A., Theodorou L.G., Charamopoulou V., Zacharaki P., Papamichael E.M. Purification and kinetics of two novel thermophilic extracellular proteases from Lactobacillus helveticus, from kefir with possible biotechnological interest. Bioresour Technol. 2008;99:5804–5813. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weizman Z. Probiotics therapy in acute childhood diarrhoea. Lancet. 2010;376:233. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S., Wang X., Du G., Zhou J., Chen J. Enhanced production of L-sorbose from D-sorbitol by improving the mRNA abundance of sorbitol dehydrogenase in Gluconobacter oxydans WSH-003. Microb Cell Fact. 2014;13:146. doi: 10.1186/s12934-014-0146-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]