Abstract

Thirteen extensively characterised grain sorghum varieties were evaluated in a series of 7 broiler bioassays. The efficiency of energy utilisation of broiler chickens offered sorghum-based diets is problematic and the bulk of dietary energy is derived from sorghum starch. For this reason, rapid visco-analysis (RVA) starch pasting profiles were determined as they may have the potential to assess the quality of sorghum as a feed grain for chicken-meat production. In review, it was found that concentrations of kafirin and total phenolic compounds were negatively correlated with peak and holding RVA viscosities to significant extents across 13 sorghums. In a meta-analysis of 5 broiler bioassays it was found that peak, holding, breakdown and final RVA viscosities were positively correlated with ME:GE ratios and peak and breakdown RVA viscosities with apparent metabolizable energy corrected for nitrogen (AMEn) to significant extents. In a sixth study involving 10 sorghum-based diets peak, holding and breakdown RVA viscosities were positively correlated with ME:GE ratios and AMEn. Therefore, it emerged that RVA starch pasting profiles do hold promise as a relatively rapid means to assess sorghum quality as a feed grain for chicken-meat production. This potential appears to be linked to quantities of kafirin and total phenolic compounds present in sorghum and it would seem that both factors depress RVA starch viscosities in vitro and, in turn, also depress energy utilisation in birds offered sorghum-based diets. Given that other feed grains do not contain kafirin and possess considerably lower concentrations of phenolic compounds, their RVA starch pasting profiles may not be equally indicative.

Keywords: Kafirin, Phenolics, Poultry, Rapid visco-analysis, Sorghum, Starch

1. Introduction

Rapid methods to assess feed grain quality are of interest to integrated chicken-meat producers and feed-millers as the quality of feed grains are important determinants of bird performance. Starch pasting profiles of feed grains assessed by rapid visco-analysis (RVA) may be a relatively rapid and accurate indicator of feed grain quality (Selle et al., 2016a). Promatest protein solubility of feedstuffs may also be indicative although it cannot be considered as rapid methodology unless it can be harnessed by near-infrared spectroscopy.

The determination of starch pasting profiles by RVA was originally developed by Charles (Chuck) Walker in relation to rain damaged wheat (Walker et al., 1988). Presently, RVA starch pasting profiles are used extensively in the human food industry but their applications in animal nutrition have been limited. However, the possibility remains that RVA starch parameters of feed grains may provide valuable indications of their quality for chicken-meat production (Masey O'Neil, 2008). Doucet et al. (2010) found strong negative correlations between dietary peak and final RVA starch viscosities with starch digestibilities at the mid-point of the small intestine in weaner pigs. Example RVA starch pasting profiles of maize, sorghum and wheat are shown in Table 1, which stem from 2 related reports (Liu et al., 2014, Truong et al., 2014) comparing the effects of phytase supplementation of broiler diets based on these 3 feed grains. Interestingly, as reported by Truong et al. (2014), 1,000 FTU/kg phytase significantly decreased peak RVA of maize- and wheat-based diets but significantly increased this parameter in sorghum-based diets.

Table 1.

Rapid visco-analysis (RVA) starch pasting profiles of maize, sorghum and wheat, adapted from Truong et al. (2014).

| Feed grain | RVA viscosity, cP |

Peak time, min | Pasting temperature, °C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak | Holding | Breakdown | Final | Setback | |||

| Maize | 1,107 | 622 | 485 | 1,056 | 434 | 4.13 | 75.1 |

| Sorghum | 1,371 | 503 | 868 | 1,206 | 703 | 4.04 | 76.3 |

| Wheat | 996 | 467 | 529 | 939 | 472 | 5.33 | 84.3 |

A number of papers have reported on the RVA starch pasting profiles of grain sorghum including Zhang and Hamaker, 2003, Zhang and Hamaker, 2005, Sopade et al., 2009 and Shewayrga et al. (2012). Several publications, including Miller et al., 1973, Atwell et al., 1988, Batey, 2007 and Acosta-Osorio et al. (2011), provide detailed explanations of RVA starch pasting profiles, which is not to be confused with starch gelatinisation. Pasting is a subsequent phenomenon to starch gelatinisation involving granular swelling, exudation of molecular components from the granule and, ultimately, total disruption of the starch granule (Atwell et al., 1988). The RVA curve depicts the impacts of agitation, temperature and time on the viscosity of the starch paste (Batey, 2007).

Wheat is the dominant feed grain for chicken-meat production in Australia and sorghum constitutes the balance but is usually perceived to be somewhat inferior to wheat; consideration has been given to this perception in several reviews (Selle et al., 2010, Selle et al., 2013, Liu et al., 2015). Contemporary Australian sorghum crops do not contain condensed tannin (Khoddami et al., 2015); however, there is the belief that the stigma associated with ‘bird-proof’ sorghums, which did contain condensed tannin, persists. Nevertheless, the performance of birds offered sorghum-based diets is variable (Hughes and Brooke, 2005). The majority of energy in poultry diets is derived from starch and the fundamental problem appears to be poor starch/energy utilisation in poultry offered sorghum-based diets (Black et al., 2005). On the basis of both in vitro (Giuberti et al., 2012) and in vivo (Truong et al., 2016a) data, the digestibility of sorghum starch is inferior to maize. In addition, sorghum-based poultry diets are associated with relatively poor pellet quality and responses in broiler performance to inclusions of exogenous enzymes may be modest.

2. Background

The focus of this review is on 13 very extensively characterized grain sorghum varieties grown in New South Wales and Queensland primarily because both their RVA starch pasting profiles and kafirin concentrations had been determined. Kafirin was quantified by methodology detailed in Truong et al. (2016a). The average amino acid profiles of kafirin in 2 sorghums, MP (107 g/kg protein, 41.1 g/kg kafirin) and HP (113 g/kg protein, 50.5 g/kg kafirin), are shown in Table 2. They are in very close agreement with data generated by Xiao et al. (2015) which represent the average amino acid profiles of kafirin in 3 grain sorghums. It is evident that kafirin contains a paucity of lysine and most essential amino acids with the noticeable exception of leucine. Kafirin is the dominant protein fraction in grain sorghum and the protein quality of this feed grain is questionable as a consequence (Selle, 2011). Barros et al. (2012) reported that condensed tannin interacts strongly with starch, decreasing its digestibility, and suggested that amylose and linear fragments of amylopectin are involved in these interactions. Importantly, none of the 13 sorghums contained a pigmented testa as detected by the Clorox bleach test (Waniska et al., 1992) and this indicates that they did not contain condensed tannin. Concentrations of ‘non-tannin’ total phenolic compounds, a range of polyphenols, free, conjugated and bound phenolic acids were determined by analytical methodology described in Khoddami et al. (2015).

Table 2.

Amino acid profiles of kafirin in MP and HP sorghums in comparison to data generated by Xiao et al. (2015).1

| Amino acid, g/100 g protein | Mean of MP and HP sorghums | Data from Xiao et al. (2015) |

|---|---|---|

| Arginine | 2.2 | 2.1 |

| Histidine | 1.9 | 1.2 |

| Isoleucine | 4.1 | 3.7 |

| Leucine | 15.8 | 16.9 |

| Lysine | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| Methionine | 1.2 | 1.3 |

| Phenylalanine | 5.7 | 5.4 |

| Threonine | 2.7 | 2.5 |

| Valine | 4.8 | 4.2 |

| Alanine | 10.1 | 11.2 |

| Aspartic acid | 6.1 | 6 |

| Glutamic acid | 24.3 | 27 |

| Glycine | 2.1 | 1.1 |

| Proline | 9.5 | 9.2 |

| Serine | 4.2 | 3.7 |

| Tyrosine | 4.7 | 4.4 |

MP and HP are 2 sorghums: MP (107 g/kg protein, 41.1 g/kg kafirin) and HP (113 g/kg protein, 50.5 g/kg kafirin).

Moreover, the 13 grain sorghum varieties were evaluated in a series of broiler bioassays on the Camden Campus of this university. Six red sorghums harvested on the Liverpool Plains in 2009 (designated as LvP 1 to LvP 6) were evaluated in sorghum-casein diets as reported by Khoddami et al. (2015). Two of these sorghums (LvP 3 and LvP 5) were subsequently compared in conventional broiler diets by Truong et al. (2015a). The balance of one white (Liberty) and 6 red sorghums (designated as FW, Block I, Tiger, JM, MP, HP), which were variously grown on the Darling Downs in Queensland or the Liverpool Plains and Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area of New South Wales, were assessed in several studies. Sorghum FW was evaluated by Truong et al. (2015b) in a study involving the addition of sodium metabisulphite and exogenous phytase to sorghum-based diets. Sorghums Block I and Tiger were evaluated by Selle et al. (2016b) in a study designed to investigate the impacts of hammer-mill screen size and grain particle size on broiler performance. Liu et al. (2016) used sorghums Block I, HP and Liberty to formulate 10 nutritionally equivalent broiler diets that were compared in an ‘equilateral triangle’ response surface design. Truong et al. (2016b) compared sorghums Block I, HP, Liberty, Tiger, MP and JM directly and in another study sorghums HP and Tiger were again assessed Truong et al. (2016c).

In the relevant studies, RVA starch pasting profiles were determined in duplicate using a RVA-4 analyser (Newport Scientific, Warriewood, Australia) via methods described by Beta and Corke (2004). In brief, finely ground sorghum grain (4.2 g) was mixed with deionized water (23.8 g) in a heating and cooling cycle of 13 min. The slurry was held at a temperature of 50°C for 1 min and then heated to 95°C and held for 2.5 min prior to cooling the slurry to 50°C and holding that temperature for 2 min. Peak, holding and final viscosities were recorded and, effectively, breakdown (peak minus holding) and setback (final minus peak) viscosities deduced and peak time and pasting temperature were monitored. Interestingly, setback viscosity or the difference between peak and final viscosities may be associated with starch retrogradation (Wang et al., 2015).

Thus, the core objective of this review is firstly to identify the factors inherent in grain sorghum that have the capacity to influence the feed grain's nutritional value as indicated their RVA starch pasting profiles. The second phase is to assess the potential of RVA starch pasting profiles as yardsticks for the quality of sorghum as a feed grain in poultry. Finally, some attention will be paid to Promatest protein solubilities of sorghum as yardsticks for the same purpose. Assessments of sorghum quality as a feed grain will focus on parameters of nutrient utilisation including apparent metabolizable energy (AME), metabolizable to gross energy ratios (ME:GE), nitrogen (N) retention and N-corrected AME (AMEn) in broiler chickens.

3. Inherent grain sorghum factors and RVA starch pasting profiles

Selected characteristics of the 13 grain sorghums are shown in Table 3; these include starch concentrations determined by NIR, amylose proportions of starch, protein contents and solubilities, kafirin concentrations, concentrations of total phenolic compounds and phytate, and grain texture as determined by the particle size index (PSI) method (Symes, 1965). In addition to total phenolics, the polyphenols analysed included anthocyanin, flavan-4-ols, luteolinidin, apigeninidin, 5-methoxy-luteolinidin and 7-methoxy-apigeninidin Also, in addition to total phenolics, the phenolic acids analysed included p-hydroxy benzoic, vanillic, caffeic, p-coumaric, ferulic, syringic and sinapic acids in their free, conjugated and bound forms. The corresponding RVA starch pasting profiles are shown in Table 4.

Table 3.

Selected characteristics of 13 grain sorghum varieties (analyses completed in duplicate).

| Item | Starch, g/kg | Crude protein, g/kg | Protein solubility, % | Kafirin, g/kg | Amylose, % of starch | Phenolic, mg GAE/g | Phytate, g/kg | Texture, PSI % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LvP 1 | 624 | 107.7 | 44.7 | 51.7 | 32 | 3.12 | 7.62 | 11 |

| LvP 2 | 638 | 105.4 | 46.8 | 44.5 | 34 | 3.45 | 7.98 | 10 |

| LvP 3 | 624 | 109.2 | 49.5 | 50.7 | 26.4 | 3.52 | 8.33 | 10 |

| LvP 4 | 649 | 101.6 | 48.1 | 45.4 | 36.9 | 3.28 | 6.74 | 12 |

| LvP 5 | 620 | 126.4 | 41.2 | 61.5 | 27.2 | 3.59 | 8.51 | 9 |

| LvP 6 | 626 | 91.7 | 44.4 | 41.9 | 31 | 3.33 | 9.4 | 11 |

| FW | 859 | 92.5 | – | 45.8 | 30.9 | 2.31 | 6.58 | 10 |

| Block I | 756 | 137.1 | – | 67.1 | 30.9 | 4.68 | 9.79 | 11 |

| Tiger | 830 | 99.9 | – | 51.3 | 26.4 | 4.12 | 8.4 | 9 |

| JM | 772 | 97.7 | – | 50.1 | 35.1 | 3.9 | 8.94 | 10 |

| Liberty | 851 | 80.9 | – | 41.4 | 35.1 | 3 | 4.93 | 11 |

| MP | 797 | 100.2 | – | 41.1 | 27.4 | 3.21 | 8.3 | 9 |

| HP | 818 | 109.1 | – | 50.5 | 29.9 | 3.52 | 7.77 | 8 |

| Mean | 728 | 104.6 | 45.8 | 50.2 | 30.7 | 3.46 | 7.92 | 10.1 |

| Standard deviation | ±98.5 | ±14.6 | ±3.0 | ±7.3 | ±3.7 | ±0.57 | ±1.31 | ±1.12 |

| Coefficient of variation | 13.50% | 14.00% | 6.60% | 14.50% | 12.10% | 16.50% | 16.50% | 11.10% |

GAE = gallic acid equivalents; PSI = particle size index; LvP = Liverpool Plains; FW = Feedworks; JM = supplier; MP = mid-protein; HP = high-protein.

Table 4.

Rapid visco-analysis (RVA) starch pasting profiles of 13 grain sorghum varieties (analyses completed in duplicate).

| Item | RVA viscosity, cP |

Peak time, min | Pasting temperature, °C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak | Holding | Breakdown | Final | Setback | |||

| LvP 1 | 2,455 | 2,262 | 194 | 5,103 | 2,841 | 5.83 | 81.9 |

| LvP 2 | 4,918 | 3,484 | 1,434 | 7,237 | 3,753 | 5.47 | 79.5 |

| LvP 3 | 4,202 | 3,088 | 1,114 | 6,644 | 3,556 | 5.53 | 78.6 |

| LvP 4 | 6,857 | 5,359 | 1,462 | 11,613 | 6,218 | 5.5 | 77.5 |

| LvP 5 | 3,750 | 3,086 | 664 | 7,132 | 4,045 | 5.73 | 79.4 |

| LvP 6 | 6,375 | 4,905 | 1,471 | 10,123 | 5,218 | 5.6 | 77.8 |

| FW | 9,511 | 5,458 | 4,053 | 8,695 | 3,238 | 5 | 73.4 |

| Block I | 2,392 | 2,091 | 300 | 4,592 | 2,501 | 5.63 | 79.9 |

| Tiger | 4,771 | 2,904 | 1,867 | 5,746 | 2,846 | 5.13 | 75.1 |

| JM | 5,559 | 3,202 | 2,357 | 5,726 | 2,524 | 5 | 73.2 |

| Liberty | 4,717 | 2,810 | 1,907 | 5,378 | 2,928 | 5.17 | 75.9 |

| MP | 3,619 | 3,022 | 597 | 6,347 | 3,325 | 5.64 | 77.9 |

| HP | 2,591 | 2,517 | 74 | 5,554 | 3,037 | 6.2 | 82.6 |

| Mean | 4,280 | 2,969 | 1,311 | 5,958 | 3,018 | 5.47 | 77.6 |

| Standard deviation | ±1,903 | ±830 | ±1,154 | ±1,083 | ±444 | ±0.42 | ±3.2 |

| Coefficient of variation | 44.50% | 28.00% | 88.00% | 18.20% | 14.70% | 7.68% | 4.12% |

LvP = Liverpool Pains; FW = Feedworks; JM = supplier; MP = mid-protein; HP = high protein.

Pearson correlations between numerous factors in sorghum and their corresponding RVA starch pasting profiles were deduced and selected examples are shown in Table 5. As is evident in this table, sorghum protein contents were associated with decreased peak and breakdown viscosities, and increased pasting temperatures, to significant extents. Sorghum starch contents could be expected to have reciprocal effects but this was not the case as there were not any significant correlations between starch contents and RVA parameters. Also, the amylose proportion of starch did not appear to influence (P > 0.35) RVA starch pasting profiles. This is in contrast to a study by Beta and Corke (2001) from which it may be deduced that amylose proportions of ten sorghums were negatively correlated to peak RVA viscosities (r = −0.838; P < 0.005) but positively correlated to final RVA viscosities (r = 0.651; P < 0.05). However, there was little variation from the mean amylose content (27.9%) across the 10 sorghums.

Table 5.

Pearson correlations between selected inherent factors and rapid visco-analysis (RVA) starch pasting profiles of 13 grain sorghum varieties.

| Factor | RVA starch pasting profile |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak | Holding | Breakdown | Final | Setback | Peak time | Temperature | |

| Protein | r = −0.575 | r = −0.454 | r = −0.597 | r = −0.297 | r = −0.143 | r = 0.505 | r = 0.560 |

| P = 0.040 | P = 0.120 | P = 0.031 | P = 0.325 | P = 0.640 | P = 0.079 | P = 0.046 | |

| Starch | r = 0.158 | r = −0.102 | r = 0.401 | r = −0.362 | r = −0.550 | r = −0.389 | r = −0.466 |

| P = 0.606 | P = 0.739 | P = 0.174 | P = 0.224 | P = 0.052 | P = 0.190 | P = 0.109 | |

| Amylose | r = 0.069 | r = 0.119 | r = 0.001 | r = 0.190 | r = 0.268 | r = −0.105 | r = −0.024 |

| P = 0.822 | P = 0.699 | P = 0.997 | P = 0.535 | P = 0.376 | P = 0.733 | P = 0.939 | |

| Kafirin | r = −0.578 | r = −0.559 | r = −0.493 | r = −0.479 | r = −0.370 | r = 0.320 | r = 0.341 |

| P = 0.038 | P = 0.047 | P = 0.087 | P = 0.098 | P = 0.213 | P = 0.286 | P = 0.254 | |

| Phytate | r = −0.362 | r = −0.255 | r = −0.405 | r = −0.141 | r = −0.067 | r = 0.273 | r = 0.229 |

| P = 0.225 | P = 0.401 | P = 0.170 | P = 0.646 | P = 0.827 | P = 0.367 | P = 0.451 | |

| Total phenolic | r = −0.566 | r = −0.558 | r = −0.471 | r = −0.425 | r = −0.258 | r = 0.141 | r = 0.193 |

| P = 0.044 | P = 0.047 | P = 0.104 | P = 0.147 | P = 0.394 | P = 0.646 | P = 0.527 | |

| 5-methoxy luteolinidin | r = 0.704 | r = 0.690 | r = 0.591 | r = 0.540 | r = 0.302 | r = −0.379 | r = −0.405 |

| P = 0.007 | P = 0.009 | P = 0.033 | P = 0.057 | P = 0.316 | P = 0.201 | P = 0.170 | |

| Bound ferulic acid | r = 0.045 | r = 0.322 | r = −0.252 | r = 0.508 | r = 0.575 | r = 0.360 | r = 0.383 |

| P = 0.884 | P = 0.284 | P = 0.406 | P = 0.076 | P = 0.040 | P = 0.227 | P = 0.197 | |

| Total ferulic acid | r = 0.022 | r = 0.304 | r = −0.277 | r = 0.496 | r = 0.570 | r = 0.381 | r = 0.399 |

| P = 0.944 | P = 0.313 | P = 0.359 | P = 0.085 | P = 0.042 | P = 0.199 | P = 0.117 | |

Phytate concentrations in sorghum did not appear to have any real influence (P > 0.15) on RVA profiles. Instructively, sorghum kafirin concentrations were associated with significant depressions in peak (r = −0.578; P < 0.04) and holding (r = −0.559; P < 0.05) viscosities with trends towards depressed breakdown (r = −0.493; P = 0.087) and final (r = −0.479; P = 0.098) RVA viscosities.

Additionally, total phenolic compounds in sorghum were associated with significantly depressed peak (r = −0.566; P < 0.05) and holding (r = −0.558; P < 0.05) viscosities. Phenolic compounds also tended to depress breakdown (r = −0.471; P = 0.104), final (r = −0.425; P = 0.087) and setback (r = −0.493; P = 0.147) RVA viscosities. Alternatively, the polyphenolic compound 5-methoxy-luteolinidin was associated with significant increases in peak, holding and final RVA viscosities.

Ferulic acid is the dominant phenolic acid in sorghum but in its free (P > 0.75) and conjugated (P > 0.125) forms it was not associated with differences in RVA profiles. As tabulated, however, bound (r = 0.575; P < 0.05) and total (r = 0.570; P < 0.05) ferulic acid were associated with significant increases in setback viscosity with positive trends evident for final viscosity.

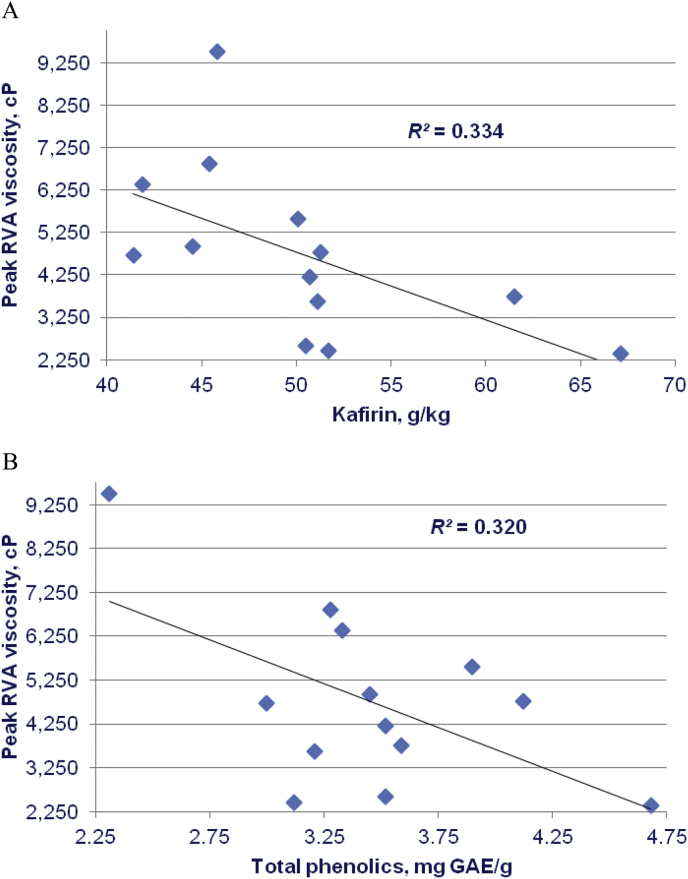

The noteworthy outcome is that concentrations of both kafirin and total phenolic compounds were associated with significant linear reductions in peak RVA viscosities as illustrated in Fig. 1. This is despite the relatively limited numbers of sorghum varieties assessed which were grown under an unknown range of environmental conditions. Catechin, a flavan-3-ol polyphenol, and ferulic acid have been shown to influence sorghum RVA starch pasting profiles (Beta and Corke, 2004). However, this is almost certainly the first investigation into the relationship between kafirin and RVA profiles in grain sorghum and it does appear that kafirin is influential.

Fig. 1.

Linear relationships between concentrations of (A) kafirin (r = −0.578; P < 0.04) and (B) total phenolic compounds (r = −0.566; P < 0.05) in 13 sorghum varieties with peak rapid visco-analysis (RVA) viscosities. GAE = gallic acid equivalent.

4. Sorghum RVA starch pasting profiles and nutrient utilisation in broiler chickens

Pearson correlations between sorghum RVA starch pasting profiles and parameters of nutrient utilisation in broiler chickens offered corresponding sorghum-based diets are shown in Table 6. The analysed data was derived from 5 experiments (Khoddami et al., 2015, Selle et al., 2016b, Truong et al., 2015a, Truong et al., 2015b, Truong et al., 2016a, Truong et al., 2016b, Truong et al., 2016c) involving 9 sorghum varieties (LvP 3, LvP 5, FW, Tiger, Block I, HP, Liberty, MP, JM). Three results for Tiger, and 2 results from both Block I and HP provided a total of 13 sets of observations.

Table 6.

Pearson correlations between sorghum rapid visco-analysis (RVA) starch pasting profiles and parameters of nutrient utilisation in broiler chickens offered corresponding sorghum-based diets.1

| RVA profile | AME | ME:GE | N retention | AMEn |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak viscosity | r = 0.475 | r = 0.810 | r = 0.587 | r = 0.588 |

| P = 0.101 | P = 0.001 | P = 0.035 | P = 0.035 | |

| Holding viscosity | r = 0.439 | r = 0.817 | r = 0.552 | r = 0.452 |

| P = 0.133 | P = 0.001 | P = 0.050 | P = 0.121 | |

| Breakdown viscosity | r = 0.468 | r = 0.749 | r = 0.571 | r = 0.644 |

| P = 0.107 | P = 0.003 | P = 0.042 | P = 0.017 | |

| Final viscosity | r = 0.444 | r = 0.764 | r = 0.383 | r = 0.322 |

| P = 0.128 | P = 0.002 | P = 0.196 | P = 0.284 | |

| Setback viscosity | r = 0.259 | r = 0.363 | r = −0.097 | r = −0.030 |

| P = 0.393 | P = 0.222 | P = 0.752 | P = 0.922 | |

| Peak time | r = −0.469 | r = −0.552 | r = −0.404 | r = −0.661 |

| P = 0.106 | P = 0.050 | P = 0.172 | P = 0.014 | |

| Pasting temperature | r = −0.408 | r = −0.559 | r = −0.405 | r = −0.618 |

| P = 0.166 | P = 0.047 | P = 0.169 | P = 0.024 |

AME = apparent metabolizable energy; ME = metabolizable energy; GE = gross energy; AMEn = apparent metabolizable energy corrected for nitrogen.

Data derived from Khoddami et al., 2015, Selle et al., 2016b, Truong et al., 2015a, Truong et al., 2015b, Truong et al., 2016a, Truong et al., 2016b, Truong et al., 2016c). P is the significance of probability value and r is the correlation coefficient.

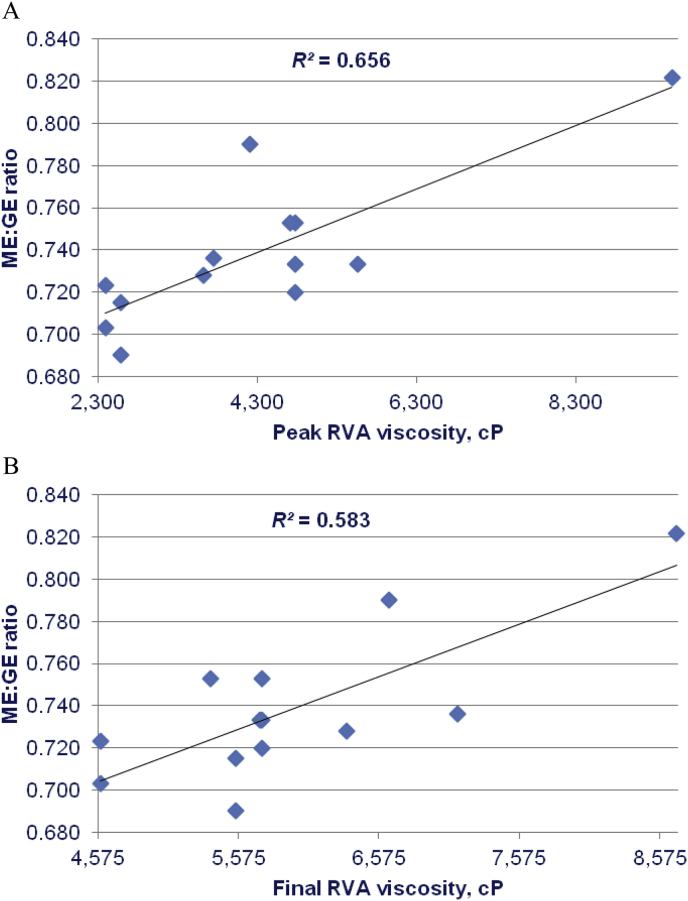

As shown in Table 6, RVA starch pasting viscosities tended to be positively correlated with AME but not to significant extents; the strongest correlation was between peak RVA viscosity and AME (r = 0.475; P = 0.101). Peak time and pasting temperature tended to be negatively correlated with AME. However, peak (r = 0.588; P < 0.04) and breakdown (r = 0.644; P < 0.02) viscosities were positively correlated with AMEn to significant extents and, similarly, peak time (r = −0.661; P < 0.015) and pasting temperature (r = −0.618; P < 0.025) were negatively correlated. RVA starch pasting viscosities were positively correlated to ME:GE ratios; these linear relationships were significant for peak (r = 0.810; P < 0.005), holding (r = 0.817; P < 0.005), breakdown (r = 0.749; P < 0.005) and final (r = 0.764; P < 0.005) RVA viscosities. Peak time (r = −0.552; P = 0.05) and pasting temperature (r = −0.559; P < 0.05) were negatively correlated with ME:GE ratios to significant extents. The linear relationships between peak and final RVA viscosities with ME:GE ratios are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Linear relationships between (A) peak (r = 0.810; P < 0.001) and (B) final (r = 0.764; P < 0.0025) rapid visco-analysis (RVA) viscosities and ME:GE ratios in broilers offered diets based on 9 sorghum varieties in 5 feeding studies [adapted from Khoddami et al., 2015, Selle et al., 2016b, Truong et al., 2015a, Truong et al., 2015b, Truong et al., 2016a, Truong et al., 2016b, Truong et al., 2016c)].

The Pearson correlations for energy utilisation parameters are valid in that the leverage of different experiments was not significant. The probability values from multiple linear regressions combining the experiments and relevant parameters are shown in parentheses (AME: P = 0.352, ME:GE ratios: P = 0.179, AMEn: P = 0.200). However, there was a significant experimental leverage (P = 0.012) for N retention and while the Pearson correlations are tabulated they are not otherwise considered. Other than 2 exceptions, RVA starch pasting profiles were not significantly correlated with weight gain, feed intake, FCR and ileal digestibilities of starch and protein (N). The 2 exceptions were setback viscosity with weight gain (−0.758; P < 0.005) and feed intake (−0.706; P < 0.01).

A sixth experiment (Liu et al., 2016) provides a unique opportunity to assess RVA starch pasting profiles in relation to bird performance. In this experiment 3 sorghums (Block I, HP, Liberty) were used to formulate 10 diets containing 620 g/kg sorghum of various blends. Thus, the RVA starch pasting profiles of the 10 dietary treatments can be calculated as shown in Table 7. This permits Pearson correlations to be established between RVA profiles and parameters of growth performance and nutrient utilisation reported by Liu et al. (2016) (Table 8) and, similarly, starch and protein (N) digestibility coefficients and disappearance rates from 2 small intestinal sites (Table 9).

Table 7.

Rapid visco-analysis (RVA) starch pasting profiles of sorghum blends constituting the basis of 10 sorghum-based dietary treatments [adapted from Liu et al. (2016)].

| Dietary treatment | RVA viscosity, cP |

Peak time, min | Pasting temperature, °C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak | Holding | Breakdown | Final | Setback | |||

| 1 | 2,392 | 2,091 | 300 | 4,592 | 2,501 | 5.63 | 79.9 |

| 2 | 2,591 | 2,517 | 74 | 5,554 | 3,037 | 6.2 | 82.6 |

| 3 | 4,717 | 2,810 | 1,907 | 5,378 | 2,928 | 5.17 | 75.9 |

| 4 | 2,492 | 2,304 | 187 | 5,073 | 2,769 | 5.92 | 81.3 |

| 5 | 3,555 | 2,451 | 1,104 | 4,985 | 2,715 | 5.4 | 77.9 |

| 6 | 3,654 | 2,664 | 991 | 5,466 | 2,983 | 5.69 | 79.3 |

| 7 | 2,814 | 2,282 | 531 | 4,885 | 2,662 | 5.65 | 79.7 |

| 8 | 2,913 | 2,495 | 418 | 5,364 | 2,929 | 5.93 | 81 |

| 9 | 3,974 | 2,641 | 1,333 | 5,276 | 2,875 | 5.42 | 77.7 |

| 10 | 3,230 | 2,470 | 760 | 5,169 | 2,819 | 5.66 | 79.4 |

Table 8.

Pearson correlations between sorghum rapid visco-analysis (RVA) starch pasting profiles and parameters of growth performance and nutrient utilisation in broiler chickens offered ten sorghum-based diets.1

| RVA profile | Gain | Feed intake | FCR | AME | ME:GE | N retention | AMEn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak viscosity | r = 0.250 | r = 0.240 | r = −0.165 | r = 0.524 | r = 0.860 | r = 0.606 | r = 0.788 |

| P = 0.486 | P = 0.505 | P = 0.650 | P = 0.120 | P = 0.001 | P = 0.063 | P = 0.007 | |

| Holding viscosity | r = 0.561 | r = 0.361 | r = −0.427 | r = 0.412 | r = 0.817 | r = 0.603 | r = 0.691 |

| P = 0.091 | P = 0.306 | P = 0.218 | P = 0.237 | P = 0.004 | P = 0.065 | P = 0.027 | |

| Breakdown viscosity | r = 0.120 | r = 0.179 | r = −0.058 | r = 0.528 | r = 0.813 | r = 0.564 | r = 0.766 |

| P = 0.741 | P = 0.621 | P = 0.873 | P = 0.117 | P = 0.004 | P = 0.090 | P = 0.010 | |

| Final viscosity | r = 0.707 | r = 0.370 | r = −0.566 | r = 0.157 | r = 0.505 | r = 0.403 | r = 0.362 |

| P = 0.022 | P = 0.292 | P = 0.088 | P = 0.665 | P = 0.137 | P = 0.248 | P = 0.304 | |

| Setback viscosity | r = 0.708 | r = 0.368 | r = −0.568 | r = 0.147 | r = 0.491 | r = 0.393 | r = 0.348 |

| P = 0.022 | P = 0.295 | P = 0.087 | P = 0.686 | P = 0.150 | P = 0.261 | P = 0.324 | |

| Peak time | r = 0.213 | r = −0.003 | r = −0.205 | r = −0.451 | r = −0.576 | r = −0.374 | r = −0.595 |

| P = 0.555 | P = 0.993 | P = 0.570 | P = 0.191 | P = 0.081 | P = 0.288 | P = 0.069 | |

| Pasting temperature | r = 0.095 | r = −0.067 | r = −0.109 | r = −0.488 | r = −0.680 | r = −0.454 | r = −0.673 |

| P = 0.795 | P = 0.855 | P = 0.764 | P = 0.152 | P = 0.031 | P = 0.187 | P = 0.033 |

FCR = feed conversion ratio; AME = apparent metabolizable energy; ME = metabolizable energy; GE = gross energy; AMEn = N-corrected AME.

adapted from Liu et al. (2016). P is the significance of probability value and r is the correlation coefficient.

Table 9.

Pearson correlations between sorghum visco-analysis (RVA) starch pasting profiles and digestibility coefficients and disappearance rates of starch and protein (N) parameters in the distal jejunum (DJ) and distal ileum (DI) in broiler chickens offered 10 sorghum-based diets.1

| RVA profile | Starch digestibility (DJ) | Starch digestibility (DI) | Starch disappearance (DJ) | Starch disappearance (DI) | Protein (N) digestibility (DJ) | Protein (N) digestibility (DI) | Protein (N) disappearance (DJ) | Protein (N) disappearance (DI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak viscosity | r = 0.240 | r = 0.186 | r = 0.634 | r = 0.633 | r = −0.043 | r = 0.015 | r = −0.403 | r = −0.682 |

| P = 0.504 | P = 0.607 | P = 0.049 | P = 0.050 | P = 0.907 | P = 0.967 | P = 0.249 | P = 0.030 | |

| Holding viscosity | r = 0.468 | r = 0.112 | r = 0.779 | r = 0.777 | r = 0.219 | r = 0.349 | r = −0.139 | r = −0.404 |

| P = 0.173 | P = 0.758 | P = 0.008 | P = 0.008 | P = 0.543 | P = 0.324 | P = 0.702 | P = 0.247 | |

| Breakdown viscosity | r = 0.140 | r = 0.199 | r = 0.536 | r = 0.535 | r = −0.134 | r = −0.107 | r = −0.469 | r = −0.734 |

| P = 0.699 | P = 0.582 | P = 0.110 | P = 0.111 | P = 0.712 | P = 0.769 | P = 0.172 | P = 0.016 | |

| Final viscosity | r = 0.557 | r = −0.001 | r = 0.678 | r = 0.676 | r = 0.425 | r = 0.589 | r = 0.186 | r = 0.024 |

| P = 0.094 | P = 0.997 | P = 0.031 | P = 0.032 | P = 0.221 | P = 0.073 | P = 0.607 | P = 0.948 | |

| Setback viscosity | r = 0.557 | r = −0.006 | r = 0.670 | r = 0.668 | r = 0.430 | r = 0.594 | r = 0.197 | r = 0.039 |

| P = 0.095 | P = 0.987 | P = 0.034 | P = 0.035 | P = 0.215 | P = 0.070 | P = 0.586 | P = 0.915 | |

| Peak time | r = 0.122 | r = −0.199 | r = −0.220 | r = −0.220 | r = 0.332 | r = 0.382 | r = 0.555 | r = 0.746 |

| P = 0.738 | P = 0.581 | P = 0.542 | P = 0.541 | P = 0.349 | P = 0.275 | P = 0.096 | P = 0.013 | |

| Pasting temperature | r = 0.027 | r = −0.204 | r = −0.346 | r = −0.346 | r = 0.264 | r = 0.288 | r = 0.536 | r = 0.761 |

| P = 0.940 | P = 0.571 | P = 0.327 | P = 0.327 | P = 0.460 | P = 0.420 | P = 0.110 | P = 0.011 |

adapted from Liu et al. (2016). P is the significance of probability value and r is the correlation coefficient.

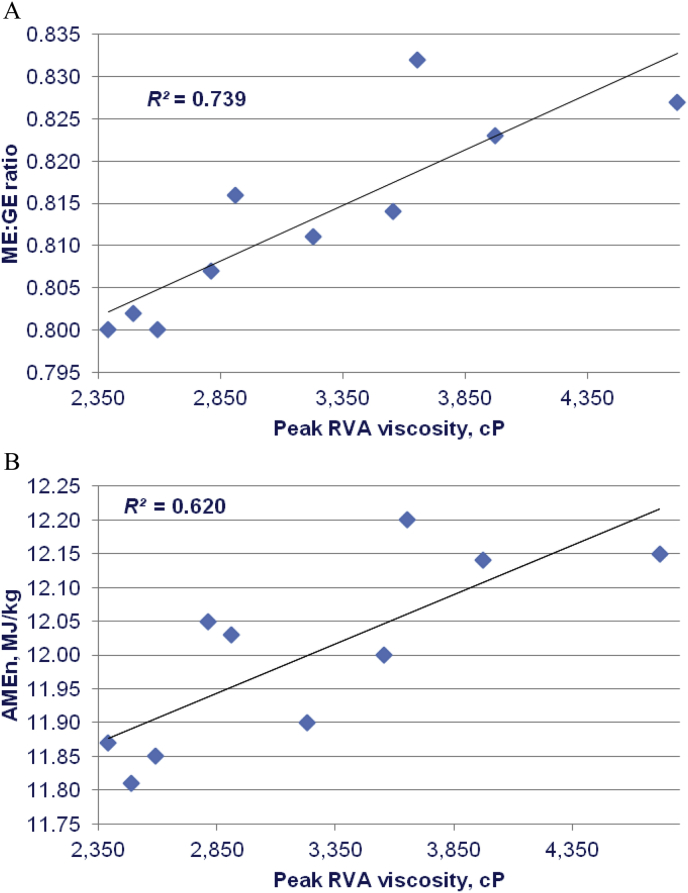

As is evident in Table 8, final and setback viscosities were positively correlated with weight gain to significant extents and tended to be negatively correlated to FCR. RVA profiles were not related to feed intake or AME. However, significant positive correlations were deduced for peak, holding and breakdown viscosities with both ME:GE ratios and AMEn and pasting temperatures were negatively correlated with ME:GE ratios and AMEn to significant extents. Also, peak, holding and breakdown viscosities tended to be positively correlated with N retention. The linear relationships between peak RVA viscosities with ME:GE ratios and AMEn are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Linear relationships between peak rapid visco-analysis (RVA) viscosity of 10 sorghum-based diets and (A) ME:GE ratios (r = 0.860; P < 0.005) and (B) AMEn (r = 0.788; P < 0.01) [adapted from Liu et al. (2016)].

As shown in Table 9, final and setback viscosities tended to be correlated with distal jejunal starch digestibility coefficients. However, peak, holding, final and setback viscosities were positively and significantly correlated with starch disappearance rates in both the distal jejunum and distal ileum. Final and setback viscosities tended to be correlated with distal ileal protein (N) digestibility coefficients. Alternatively, peak and breakdown viscosities were negatively and significantly correlated with protein (N) disappearance rates in the distal ileum; whereas, peak time and pasting temperature were positively and significantly correlated with distal ileal protein (N) disappearance rates. Collectively, this suggests that sorghums with high starch paste viscosities may be associated with rapid starch disappearance but slow protein (N) disappearance rates.

5. Sorghum protein solubilities and nutrient utilisation in broiler chickens

As documented in Table 3, the Promatest protein solubilities of the 6 red sorghums harvested on the Liverpool Plains were determined by methodology outlined by Odjo et al. (2012). Pearson correlations between protein solubility, kafirin and crude protein contents of 6 red sorghums with parameters of nutrient utilisation of birds offered corresponding sorghum-casein diets are shown in Table 10. Interestingly, there were positive correlations between sorghum protein solubility and parameters of energy utilisation including AME (r = 0.874; P < 0.025), ME:GE ratios (r = 0.862; P < 0.03), and AMEn (r = 0.827; P < 0.05). Kafirin is a poorly soluble protein source; however, the negative correlation between sorghum protein solubility and kafirin (r = −0.542; P > 0.25) was not significant. This may simply reflect the small number of sorghums assayed. Alternatively, kafirin and glutelin are the 2 prominent protein fractions in grain sorghum and both are located in the endosperm (Selle, 2011). Kafirin is found as discrete protein bodies which, together with starch granules, are embedded in the glutelin protein matrix of sorghum endosperm. Thus the solubilities of both protein fractions may play a role in determining how efficiently sorghum starch/energy is utilised. Far more attention is paid to kafirin but Beckwith (1972) described glutelin and its role in starch–protein interactions in sorghum probably deserves more consideration. These preliminary outcomes do suggest that the protein solubility of sorghum and other key feedstuffs for poultry diets merits further investigations.

Table 10.

Pearson correlations between protein solubility, kafirin and crude protein contents of 6 red sorghums with parameters of nutrient utilisation of birds offered corresponding sorghum-casein diets.1

| Item | Protein solubility | Kafirin | Protein | AME | ME:GE ratio | N retention | AMEn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein solubility | 1.000 | ||||||

| Kafirin | r = −0.542 | 1.000 | |||||

| P = 0.267 | |||||||

| Protein | r = −0.440 | r = 0.954 | 1.000 | ||||

| P = 0.383 | P = 0.003 | ||||||

| AME | r = 0.874 | r = −0.537 | r = −0.455 | 1.000 | |||

| P = 0.023 | P = 0.272 | P = 0.365 | |||||

| ME:GE ratio | r = 0.862 | r = −0.687 | r = −0.625 | r = 0.970 | 1.000 | ||

| P = 0.027 | P = 0.131 | P = 0.184 | P = 0.001 | ||||

| N retention | r = 0.509 | r = −0.465 | r = −0.522 | r = 0.524 | r = 0.480 | 1.000 | |

| P = 0.302 | P = 0.353 | P = 0.288 | P = 0.286 | P = 0.335 | |||

| AMEn | r = 0.827 | r = −0.641 | r = −0.536 | r = 0.981 | r = 0.976 | r = 0.478 | 1.000 |

| P = 0.042 | P = 0.170 | P = 0.273 | P = 0.001 | P = 0.001 | P = 0.338 |

AME = apparent metabolizable energy; ME = metabolizable energy; GE = gross energy; AMEn = N-corrected AME.

adapted from Khoddami et al. (2015). P is the significance of probability value and r is the correlation coefficient.

6. Conclusions

It is noteworthy that concentrations of kafirin and total phenolic compounds in the 13 sorghum varieties assessed were negatively correlated with peak and holding RVA viscosities to significant extents. The negative influence of phenolics is consistent with data reported in Lemlioglu-Austin et al. (2012) as these researchers found that sorghum extracts containing phenolic compounds significantly reduced final and setback viscosities of maize starch. However, this is almost certainly the first time that the negative influence of kafirin on RVA starch pasting profiles has been reported. The implication is that both kafirin and certain phenolic compounds are interacting with starch.

Our contention is that ME:GE ratios provide a sensitive indication of the efficiency of energy utilisation. Therefore, it is instructive that peak, holding, breakdown and final RVA viscosities were positively correlated to ME:GE ratios to significant extents across 5 experiments. In addition, similar observations for peak, holding and breakdown viscosities were made in the sixth experiment (Liu et al., 2016). It is tempting to attribute the genesis of these positive relationships to the negative impacts of kafirin and phenolic compounds on starch pasting viscosities which is being reflected as inferior efficiency of energy utilisation in poultry. The probability that ‘non-tannin’ phenolic compounds have this capacity was specifically considered by Khoddami et al. (2015). Axiomatically, white sorghum varieties will contain less polyphenols than red sorghums and quite possibly less phenolic acids; on this basis the likelihood is that broiler chickens offered white sorghum-based diets will outperform their counterparts on red sorghum-based diets.

The importance of starch–protein interactions in relation to utilisation of energy derived from feed grains in poultry is recognized (Rooney and Pflugfelder, 1986). In sorghum, the focus is on kafirin protein bodies and starch granules which are both embedded in the glutelin protein matrix of sorghum endosperm. The consensus is that kafirin impedes starch utilisation (Taylor, 2005, Taylor and Emmambux, 2010) although dissenting opinions have been expressed (Gidley et al., 2011). However, 3 of our studies (Truong et al., 2015b, Truong et al., 2016b, Liu et al., 2016) strongly indicate that kafirin does indeed impede starch energy utilisation in sorghum-based poultry diets although the underlying biophysical and biochemical interactions have not been defined precisely. The depressive impacts of kafirin on RVA starch viscosities reported herein are entirely consistent with the proposition that kafirin has a deleterious influence on the efficiency of energy utilisation of broiler chickens offered sorghum-based diets. Of real concern is the possibility that the kafirin proportion of sorghum protein has increased in recent decades as an inadvertent consequence of breeding programs (Selle, 2011, Liu et al., 2015).

Finally, the determination of RVA starch pasting profiles of feed grains is a relatively rapid, inexpensive procedure. In the case of sorghum, these findings suggest that varieties with high starch pasting viscosities, especially high peak RVA viscosities, will support better bird performance. The likelihood is that such varieties will have low protein and kafirin contents and low concentrations of phenolic compounds. However kafirin is unique to sorghum and sorghum contains substantially more phenolic compounds than other feed grains (Bravo, 1998). Thus, our conclusion is that RVA starch pasting profiles do have real potential to assess the quality of sorghum as a feed grain for chicken-meat production but it is problematic if this potential extends to other feed grains.

Acknowledgments

We would especially like to thank Dr Karlie Neilsen and the Australian Proteome Analysis Facility (Macquarie University) for the kafirin quantifications, RIRDC Chicken-meat for funding the majority of the relevant studies, Dr David Cadogan and Feedworks for their involvement and the Poultry CRC for supporting the PhD candidatures of Ms Ha Truong and Ms Amy Moss.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

References

- Acosta-Osorio A.A., Herrera-Ruiz G., Pineda-Gómez P., Martínez-Bustos F., Gaytán M., Rodríguez-García M.E. Analysis of the apparent viscosity of starch in aqueous suspension within agitation and temperature by using rapid visco analyser system. Mech Eng Res. 2011;1:110–124. [Google Scholar]

- Atwell W.A., Hood L.F., Lineback D.R. The terminology and methodology associated with basic starch phenomena. Cereal Foods World. 1988;33 306, 308, 310–311. [Google Scholar]

- Barros F., Awika J.M., Rooney L.W. Interaction of tannins and other sorghum phenolic compounds with starch and effects on in vitro starch digestibility. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:11609–11617. doi: 10.1021/jf3034539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batey I.L. Interpretation of RVA curves. In: Crosbie G.B., Ross A.S., editors. The RVA handbook. AACC International; St Paul, Minnesota: 2007. pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Beckwith A.C. Grain sorghum glutelin: isolation and characterization. J Agric Food Chem. 1972;20:761–764. [Google Scholar]

- Beta T., Corke H. Genetic and environmental variation in sorghum starch properties. J Cereal Sci. 2001;34:261–268. [Google Scholar]

- Beta T., Corke H. Effect of ferulic acid and catechin on sorghum and maize starch pasting properties. Cereal Chem. 2004;81:418–422. [Google Scholar]

- Black J.L., Hughes R.J., Nielsen S.G., Tredrea A.M., MacAlpine R., van Barneveld R.J. The energy value of cereal grains, particularly wheat and sorghum, for poultry. Proc Aust Poult Sci Symp. 2005;17:21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo L. Polyphenols: chemistry, dietary sources, metabolism, and nutritional significance. Nutr Rev. 1998;56:317–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1998.tb01670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucet F.J., White G.A., Wulfert F., Hill S.E., Wiseman J. Predicting in vivo starch digestibility coefficients in newly weaned piglets from in vitro assessment using multivariate analysis. Br J Nutr. 2010;103:1309–1318. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509993217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidley M.J., Flanagan B.M., Sharpe K., Sopade P.A. vol. 18. University of New England; Armidale, NSW: 2011. pp. 207–213. (Starch digestion in monogastrics – mechanisms and opportunities. Recent advances in animal nutrition – Australia). [Google Scholar]

- Giuberti G., Gallo A., Cerioli C., Masoero F. In vitro starch digestion and predicted glycemic index of cereal grains commonly utilized in pig nutrition. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2012;174:163–173. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes R.J., Brooke G. Variation in the nutritive value of sorghum – poor quality grain or compromised health of chickens? Proc Aust Poult Sci Symp. 2005;17:35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Khoddami A., Truong H.H., Liu S.Y., Roberts T.H., Selle P.H. Concentrations of specific phenolic compounds in six red sorghums influence nutrient utilisation in broilers. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2015;210:190–199. [Google Scholar]

- Lemlioglu-Austin D., Turner N.D., McDonough C.M., Rooney L.W. Effect of sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench] crude extracts on starch digestibility, estimated glycaemic index (EGI), and resistant starch (RS) contents of porridges. Molecules. 2012;17:11124–11138. doi: 10.3390/molecules170911124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.Y., Cadogan D.J., Péron A., Truong H.H., Selle P.H. Effects of phytase supplementation on growth performance, nutrient utilization and digestive dynamics of starch and protein in broiler chickens offered maize-, sorghum- and wheat-based diets. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2014;197:164–175. [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.Y., Fox G., Khoddami A., Neilsen K.A., Truong H.H., Moss A.F. Grain sorghum: a conundrum for chicken-meat production. Agriculture. 2015;5:1224–1251. [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.Y., Truong H.H., Khoddami A., Moss A.F., Thomson P.C., Roberts T.H. Comparative performance of broiler chickens offered ten equivalent diets based on three grain sorghum varieties as determined by response surface mixture design. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2016;218:70–83. [Google Scholar]

- Masey O'Neil H.V. University of Nottingham; UK: 2008. Influence of storage and temperature treatment on nutritional value of wheat for poultry. [Doctor degree thesis dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- Miller B.S., Derby R.I., Trimbo H.B. A pictorial explanation for the increase in viscosity of a heated wheat starch-water suspension. Cereal Chem. 1973;50:271–280. [Google Scholar]

- Odjo S., Malumba P., Dossou J., Janas S., Bera F. Influence of drying and hydrothermal treatment of corn on the denaturation of salt-soluble proteins and color parameters. J Food Eng. 2012;109:561–570. [Google Scholar]

- Rooney L.W., Pflugfelder R.L. Factors affecting starch digestibility with special emphasis on sorghum and corn. J Anim Sci. 1986;63:1607–1623. doi: 10.2527/jas1986.6351607x. TARIBILITY. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selle P.H., Cadogan D.J., Li X., Bryden W.L. Implications of sorghum in broiler chicken nutrition. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2010;156:57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Selle P.H. The protein quality of sorghum grain. Proc Aust Poult Scie Symp. 2011;22:147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Selle P.H., Liu S.Y., Cowieson A.J. Sorghum: an enigmatic grain for chicken-meat production. In: Parra Patricia C., editor. Sorghum: production, growth habits and health benefits. Nova Publishers Inc. Hauppauge; NY: 2013. pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Selle P.H., Khoddami A., Moss A.F., Truong H.H., Liu S.Y. RVA starch pasting profiles may be indicative of feed grain quality. Proc Aust Poult Sci Symp. 2016;27:255–258. [Google Scholar]

- Selle P.H., Truong H.H., Khoddami A., Moss A.F., Roberts T.H., Liu S.Y. The impacts of hammer-mill screen size and grain particle size on the performance of broiler chickens offered diets based on two red sorghum varieties. Br Poult Sci. 2016 doi: 10.1080/00071668.2016.1257777. [accepted for publication] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shewayrga H., Sopade P.A., Jordan D.R., Godwin I.D. Characterisation of grain quality in diverse sorghum germplasm using a Rapid Visco-Analyzer and near infrared reflectance spectroscopy. J Sci Food Agric. 2012;92:1402–1410. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.4714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sopade P.A., Mahasukhonthachat K., Gidley M.J. Manipulating pig production XII. Australasian Pig Science Association; 2009. Assessing in vitro starch digestibility of sorghum using its rapid visco-analysis (RVA) pasting parameters; p. 63. [Google Scholar]

- Symes K.J. The inheritance of grain hardness in wheat as measured by the particle size index. Austr Agric Res. 1965;16:113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J.R.N. Non-starch polysaccharides, protein and starch: form function and feed – highlights on sorghum. Proc Aust Poult Sci Symp. 2005;17:9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J.R.N., Emmambux M.N. Developments in our understanding of sorghum polysaccharides and their health benefits. Cereal Chem. 2010;87:263–271. [Google Scholar]

- Truong H.H., Yu S., Peron A., Cadogan D.J., Khoddami A., Roberts T.H. Phytase supplementation of maize-, sorghum- and wheat-based broiler diets with identified starch pasting properties influences phytate (IP6) and sodium jejunal and ileal digestibility. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2014;198:248–256. [Google Scholar]

- Truong H.H., Cadogan D.J., Liu S.Y., Selle P.H. Addition of sodium metabisulfite and microbial phytase, individually and in combination, to a sorghum-based diet for broiler chickens from 7 to 28 days post-hatch. Anim Prod Sci. 2015;56:1484–1491. [Google Scholar]

- Truong H.H., Neilson K.A., McInerney B.V., Khoddami A., Roberts T.H., Liu S.Y. Performance of broiler chickens offered nutritionally-equivalent diets based on two red grain sorghums with quantified kafirin concentrations as intact pellets or re-ground mash following steam-pelleting at 65 or 97°C conditioning temperatures. Anim Nutr. 2015;1:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong H.H., Liu S.Y., Selle P.H. Starch utilisation in chicken-meat production: the foremost influential factors. Anim Prod Sci. 2016;56:797–814. [Google Scholar]

- Truong H.H., Neilson K.A., McInerney B.V., Khoddami A., Roberts T.H., Cadogan D.J. Comparative performance of broiler chickens offered nutritionally equivalent diets based on six diverse, ‘tannin-free’ sorghum varieties with quantified concentrations of phenolic compounds, kafirin, and phytate. Anim Prod Sci. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Truong H.H., Neilson K.A., McInerney B.V., Khoddami A., Roberts T.H., Liu S.Y. Sodium metabisulphite enhances energy utilisation in broiler chickens offered sorghum-based diets with five different grain varieties. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2016;219:159–174. [Google Scholar]

- Walker C.E., Ross A.S., Wrigley C.W., MacMaster G.J. Accelerated starch-paste characterization with the rapid visco-analyzer. Cereal Foods World. 1988;33:491–494. [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Li C., Copeland L., Niu Q., Wang S. Starch retrogradation: a comprehensive review. Compr Rev Food Saf Food Secur. 2015;14:568–585. [Google Scholar]

- Waniska R.D., Hugo L.F., Rooney L.W. Practical methods to determine the presence of tannins in sorghum. J Appl Poult Res. 1992;1:122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J., Li Y., Li J., Gonzalez A.P., Xia Q., Huang Q. Structure, morphology, and assembly behavior of kafirin. J Agric Food Chem. 2015;63:216–224. doi: 10.1021/jf504674z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang A., Hamaker B.R. A three component interaction among starch, protein, and free fatty acids revealed by pasting profiles. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:2797–2800. doi: 10.1021/jf0300341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang A., Hamaker B.R. Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench) flour pasting properties influenced by free fatty acids and protein. Cereal Chem. 2005;82:534–540. [Google Scholar]