Abstract

To understand the effects of niacin on the ruminal microbial ecology of cattle under high-concentrate diet condition, Illumina MiSeq sequencing technology was used. Three cattle with rumen cannula were used in a 3 × 3 Latin-square design trial. Three diets were fed to these cattle during 3 periods for 3 days, respectively: high-forage diet (HF; forage-to-concentrate ratio = 80:20), high-concentrate diet (HC; forage-to-concentrate ratio = 20:80), and HC supplemented with 800 mg/kg niacin (HCN). Ruminal pH was measured before feeding and every 2 h after initiating feeding. Ruminal fluid was sampled at the end of each period for microbial DNA extraction. Overall, our findings revealed that subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA) was induced and the α-diversity of ruminal bacterial community decreased in the cattle of HC group. Adding niacin in HC could relieve the symptoms of SARA in the cattle but the ruminal pH value and the Shannon index of ruminal bacterial community of HCN group were still lower than those of HF group. Whatever the diet was, the ruminal bacterial community of cattle was dominated by Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes and Proteobacteria. High-concentrate diet significantly increased the abundance of Prevotella, and decreased the abundance of Paraprevotella, Sporobacter, Ruminococcus and Treponema than HF. Compared with HC, HCN had a trend to decrease the percentage of Prevotella, and to increase the abundance of Succiniclasticum, Acetivibrio and Treponema. Increasing concentrate ratio could decrease ruminal pH value, and change the ruminal microbial composition. Adding niacin in HC could increase the ruminal pH value, alter the ruminal microbial composition.

Keywords: Ruminal microbial ecology, α-diversity, Niacin, High-concentrate diet condition, Cattle

1. Introduction

The health and high production performance of ruminants rely on equilibrium of ruminal microbial ecosystem (Welkie et al., 2010, Kim et al., 2011). The diet is one of the most critical influences on the ruminal microbes (Larue et al., 2005). In recent years, concentrate feed was widely served as an energy supplement in finishing cattle and high yield dairy cow production. However, the ruminal environment should change with the increase of the concentrate ratio resulting in the change of ruminal bacterial community (Zened et al., 2013, Petri et al., 2013). And in turn the changing ruminal bacterial should lead to a metabolic disturbance and cause the ruminal environment to change. Han et al. (2011) reported as the dietary non-fiber carbohydrate:neutral detergent fiber ratio increased, the ruminal pH decreased and the rumen starch decomposing bacteria, Lactobacillus, Megasphaera elsdenii and Selenomonas ruminantium number tended to increase, and the lactic acid bacteria proliferated particularly. Tajima et al. (2001) observed an increase in the number of Prevotella in the rumen of lactating cow during subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA). Similarly, Khafipour et al. (2009) found the proportion of Bacteroidetes decreased in the rumen as a result of SARA in dairy cattle.

The B-vitamin niacin function as a component of the coenzyme NAD(H) and NADP(H), which plays a critical role in the metabolism of carbohydrate, lipids and protein. It was reported that niacin supplementation could improve the production performance of high-performing ruminants (Shields et al., 1983, Drackley et al., 1998), particularly with high-concentrate diet (HC) relying on regulating the ruminal lactic acid metabolism and stabilizing the ruminal pH (Zhang et al., 2014). Besides, niacin could promote the growth of ruminal microbes, maintain the stability of the microbial community, and avoid the accumulation of lactic acid in rumen (Doreau and Ottou, 1996, Yang et al., 2013). In our earlier works, 800 mg/kg niacin (about 6 g/d) supplementation in HC could inhibit the proliferation of Bovine Streptococcus, a main lactic acid-producing bacterium (Zhang et al., 2014). It was also reported an increase in total protozoa (Wang et al., 2002; Doreau and Ottou, 1996), especially the number of Entodinia in ruminal fluid due to niacin feeding (Niehoff et al., 2009). To understand more functions of niacin on the ruminant production, this study was conducted to assess the effects of HC supplemented with or without niacin on the bacterial community in the rumen of cattle, using Illumina MiSeq sequencing.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Animals and experimental design

Three ruminal cannulated Jinjiang cattle (a native breed of Jiangxi Province in southern China, 400 ± 20 kg body weight) were used in this study. The cattle were used to high-forage diet (HF) with free range model in the past time. Now they were fed higher ratio of concentrate in the diet for the potential for producing higher-quality beef (Zhang and Yuan, 2012).

Cattle were assigned to 3 treatments: HF (forage-to-concentrate ratio = 80:20), HC (forage-to-concentrate ratio = 20:80), and HCN (HC supplemented with 800 mg/kg niacin) in a 3 × 3 Latin-square design. We used straw as forage, and the composition of the concentrate is listed in Table 1. Diets were formulated according to the China Feeding Standard of Beef Cattle (NY/T815-2004). The niacin used in this study was produced by Tianjin Zhongrui Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd., China (Assay ≥ 99%). Cattle were kept in individual stalls. They had free access to water and received 10 kg of dry matter daily in 2 equal meals at 08:00 and 18:00.

Table 1.

Ingredients and chemical composition of concentrate diets (DM basis).

| Item | Content |

|---|---|

| Ingredients, % | |

| Corn | 66.00 |

| Wheat bran | 17.00 |

| Soybean meal | 4.00 |

| Cottonseed meal | 10.00 |

| NaCl | 0.60 |

| Limestone | 0.80 |

| CaCO3 | 0.60 |

| Pre-mix1 | 1.00 |

| Chemical composition2, % | |

| Nemf, MJ/kg | 6.32 |

| Crude protein | 13.87 |

| Ca | 0.47 |

| P | 0.30 |

Nemf = total net energy.

Pre-mix provided per kilogram diet: 0.4 g Cu, 2.50 g Fe, 1.50 g Mn, 3.00 g Zn, 0.01 g Se, 0.05 mg I, 0.01 g Co, 25.00 g Mg, 300,000 IU of vitamin A, and 1,000 IU of vitamin E.

The values of chemical composition were calculated.

The trial included 14 days of washout sub period during which all cattle received HF, and then 3 days of treatment period in which each cattle received 1 of the 3 experimental diets. The cattle were fed HC or HCN after fasting for 24 h which was designed by Goad et al. (1998) to enhance the stress of feed changing.

2.2. Sample collection

Ruminal pH was determined before feeding and every 2 h after initiating feeding. A ruminal fluid of 50 mL was sampled from each cattle at the end of trial (72 h after initiating feeding). Whole liquid fraction was collected from the ventral region of the rumen, and strained through the 200 μm2 stainless steel membrane (collected). All samples were immediately stored at −80 °C until further analysis.

2.3. DNA extraction and MiSeq sequencing

Total genomic DNA of the samples was extracted by using the TIANamp Bacteria DNA Kit (TransGen Biotech, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA purity and concentration were analyzed by spectrophotometric quantification and NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotomer. The extracted quality qualified DNA were stored −20 °C for the follow-up testing. To analyze the taxonomic composition of the bacterial community, universal primers (515F 5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGG-3′ and 907R 5′-CCGTCAATTCMTTTRAGTTT-3′) targeting the V4 to V5 region of 16S rRNA gene were chosen for the amplification and subsequent pyrosequencing of the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) products. The PCR amplification was performed in a 20 μL reaction system by using TransGen AP221-02: TransStart Fastpfu DNA Polymerase (TransGen Biotech, China). The amplification was implemented in an ABI GeneAmp 9700 (ABI, USA) under the following conditions: 95 °C for 2 min, 25 cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 45 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min, 10 °C until halted by user. All PCR products were visualized on agarose gels (2% in TBE buffer) containing ethidium bromide, and purified by using AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (AXYGEN, USA). The DNA concentration of each PCR product was determined using a Quant-iT PicoGreen double stranded DNA assay (Promega, USA), Before pyrosequencing, we equally mixed the DNA samples, selected the DNA samples that meet the requirements and then stored the prepared DNA samples in the TE buffer, loaded a 1.5 mL nonstick tube, sealed with the parafilm, and made marks. We send the samples using dry ice using MiSeq on Illumina MiSeq PE250 to Major bio Bio-Pharm Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China.

2.4. Taxonomical classification

After MiSeq sequencing, sequence reads were preprocessed according to the tags with no ambiguous base pairs. The primers were removed, and the sequences were trimmed to remove low quality sequences. After that, sets of sequences with greater than or equal to 97% identity were defined as operational taxonomic units (OTU). Operational taxonomic units were assigned to a taxonomy using the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) Naive Bayes classifier. From these, the Chao, ACE and the Shannon index were calculated by mothur.

2.5. Statistical analysis

The relative abundance of bacteria in the rumen fluid was analyzed by ANOVA, using the General Linear Model of SPSS (version 17.0), according to the model shown below:

where Y is the observation for dependent variables, μ is the mean, C, P and D are the effects of cattle, period and dietary, respectively, and ɛ is the residual error. Very significant differences among treatments were declared at P < 0.01, significant differences at P < 0.05, and trends at P < 0.1.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of diets on feed intakes and ruminal pH

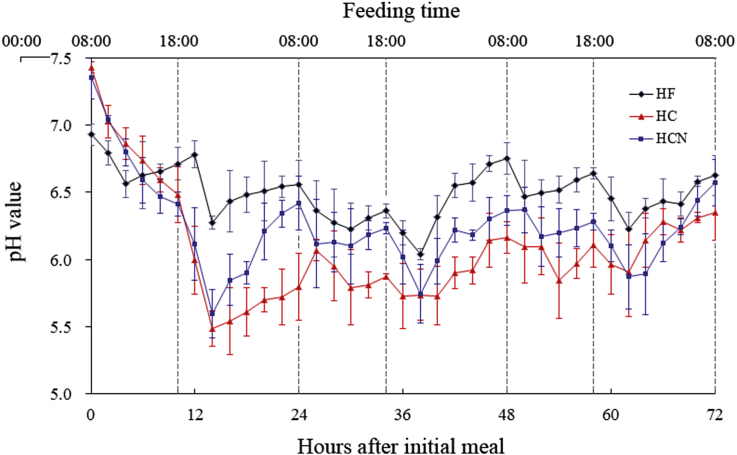

High-forage diet group consumed all of feed offered all the time. But for HC and HCN groups, the feed intakes were only 50% and 40% at the end of the trial, respectively. High-forage diet group had the highest ruminal pH in all groups stabilizing at 5.8 to 6.9 during the whole trial period. From 12 to 24 h, the ruminal pH of HC group below 5.8 lasted about 12 h and then recovered slowly. The ruminal pH of HCN group was the same as that of HC group in the first 14 h, but then it was higher than that of HC group after 14 h (Fig. 1). Supplementation of niacin shortened the duration time of lower pH.

Fig. 1.

Effects of diets on ruminal pH. HF = high-forage diet; HC = high-concentrate diet; HCN = HC + niacin diet.

3.2. Operational taxonomic units and α-diversity of ruminal bacterial community

After Miseq sequencing of 9 samples, 190,461 high-quality reads were used for downstream analysis and clustering of sequences yielded 998 OTU at 97% similarity. The mean Chao, ACE and Shannon index estimators of ruminal bacterial community were 807 ± 33, 813 ± 29 and 4.61 ± 0.26 in Jinjiang cattle, respectively. There were no differences in the Chao and ACE index in all groups (P > 0.1) (Table 2). High-forage diet group had the highest OTU and Shannon index in all treatments. Increasing concentrate ratio in diet reduced the number of OTU (P > 0.1) and Shannon index (P < 0.01). Adding niacin in HC got much lower OTU (P < 0.1) and higher Shannon index (P > 0.1) than HC.

Table 2.

Estimators of diversity with Jinjiang cattle's ruminal bacteria.

| Item | Dietary treatments |

P-value1 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF | HC | HCN | P1 | P2 | P3 | |

| Observed OTU2 | 724 | 705 | 627 | ns | * | + |

| Chao | 836 | 832 | 772 | ns | ns | ns |

| ACE | 841 | 818 | 762 | ns | ns | ns |

| Shannon index | 4.96 | 4.35 | 4.52 | ** | ** | ns |

HF = high-forage diet; HC = high-concentrate diet; HCN = HC + niacin diet; OTU = operational taxonomic units.

P1 = HC vs. HF; P2 = HCN vs. HF; P3 = HC vs. HCN; “ns” means P > 0.1; “+” means P < 0.1; “*” means P < 0.05; “**” means P < 0.01.

At 97% similarity.

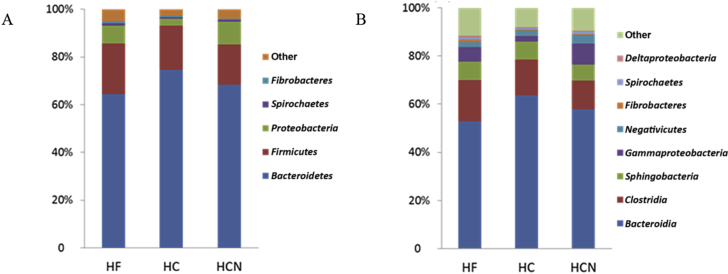

3.3. Ruminal bacterial composition

Within the bacteria population, 15 phyla, 23 classes, 26 families and 58 genera were observed across all samples of cattle. Bacteroidetes was the predominant phylum with a relative abundance of 69.13%. Firmicutes was the second abundant phylum (18.78%), followed by Proteobacteria (6.73%) as shown in Fig. 2A. The 3 phyla represented nearly 95% of total sequences. At the class level (Fig. 2B), Bacteroidetes was dominated by Bacteroidia (58.16%) and Sphingobacteria (7.28%). Clostridia class (14.55%) made a significant contribution to the Firmicutes phylum, followed by Negativicutes (2.59%). Regarding Proteobacteria phylum, the major class was Gamma proteobacteria (5.79%).

Fig. 2.

Percentage contribution of sequences (%) evaluated at the phylum (A) and class (B) levels to the total number of sequences in the database. HF = high-forage diet; HC = high-concentrate diet; HCN = HC + niacin diet.

Compared with HF group, HC group increased the percentage of Bacteroidia phylum (P < 0.1), and decreased the proportions of Spirochaetes (P < 0.1). There was no difference in the percentage of Bacteroidia phyla between HCN and HC groups (P > 0.1). But the relative abundance of Proteobacteria in HCN group ruminal fluid was 3.1 times higher than that in HC group (P < 0.1), and 26% higher than that in HF group. High-concentrate diet group also increased the percentage of Bacteroidia class (P < 0.1) and decreased the proportions of Spirochaetes class (P < 0.1). In HCN group, the percentage of Clostridia class was lower and Negativicutes class was higher than those in HF group (P < 0.1). Compared with HC, the addition of niacin increased the percentage of 2 classes encompassing Negativicutes and Spirochaetes (P < 0.1).

The diet had a number of effects on ruminal bacteria families (Table 3). Compared with HF, HC increased the percentage of Prevotellaceae (P < 0.05), and decreased the proportions of Lachnospiraceae (P < 0.1). In HCN group, the percentage of Acidaminococcaceae was higher (P < 0.1), and the proportions of Lachnospiraceae (P < 0.05) and Ruminococcaceae (P < 0.1) were lower than those in HF group. Compared with HC alone, adding niacin increased the percentage of Acidaminococcaceae, Succinivibrionaceae and Spirochaetaceae (P < 0.1), and decreased the proportions of Prevotellaceae and Lachnospiraceae (P < 0.1).

Table 3.

Percent abundance of taxa to the rumen bacteria affected by dietary changes.

| Classification | Dietary treatments |

P-value1 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF | HC | HCN | P1 | P2 | P3 | |

| Bacteroidetes | 64.67 | 74.59 | 68.42 | + | ns | ns |

| Bacteroidia | 52.88 | 63.76 | 57.84 | + | ns | ns |

| Prevotellaceae | 36.26 | 53.16 | 41.87 | * | ns | + |

| Prevotella | 28.97 | 49.47 | 36.76 | * | ns | + |

| Paraprevotella | 3.08 | 1.03 | 1.48 | ** | ** | + |

| Porphyromonadaceae | 1.89 | 1.82 | 2.70 | ns | ns | ns |

| Paludibacter | 1.17 | 1.31 | 1.39 | ns | ns | ns |

| Rikenellaceae | 2.28 | 1.15 | 1.29 | ns | ns | ns |

| Rikenella | 2.28 | 1.15 | 1.29 | ns | ns | ns |

| Sphingobacteria | 7.73 | 7.51 | 6.59 | ns | ns | ns |

| Sphingobacteriaceae | 3.93 | 3.47 | 1.33 | ns | ns | ns |

| Treponema | 0.51 | 0.22 | 0.44 | * | ns | + |

| Firmicutes | 21.20 | 18.4 | 16.75 | ns | ns | ns |

| Clostridia | 17.03 | 14.67 | 11.94 | ns | + | ns |

| Ruminococcaceae | 9.33 | 7.60 | 7.06 | ns | + | ns |

| Clostridium_IV | 1.77 | 1.33 | 0.89 | ns | ns | ns |

| Acetivibrio | 1.11 | 1.01 | 1.37 | ns | ns | + |

| Ruminococcus | 1.53 | 0.85 | 0.56 | * | * | ns |

| Saccharofermentans | 0.63 | 0.49 | 0.36 | ns | ns | ns |

| Sporobacter | 0.53 | 0.27 | 0.34 | * | * | ns |

| Lachnospiraceae | 4.89 | 3.79 | 2.74 | + | * | + |

| Lachnospiracea_incertae_sedis | 0.68 | 0.33 | 0.27 | + | + | ns |

| Butyrivibrio | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.65 | ns | ns | ns |

| Clostridiales_Incertae_Sedis_XIII | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.36 | ns | ns | ns |

| Anaerovorax | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.36 | ns | * | + |

| Negativicutes | 2.06 | 2.15 | 3.56 | ns | + | + |

| Acidaminococcaceae | 1.62 | 1.60 | 2.56 | ns | + | + |

| Succiniclasticum | 1.62 | 1.60 | 2.56 | ns | + | + |

| Proteobacteria | 7.59 | 3.07 | 9.53 | ns | ns | + |

| Gamma proteobacteria | 6.12 | 2.41 | 8.85 | ns | ns | ns |

| Succinivibrionaceae | 2.03 | 0.57 | 2.08 | ns | ns | + |

| Succinivibrio | 0.92 | 0.31 | 1.60 | ns | ns | ns |

| Ruminobacter | 0.97 | 0.05 | 0.30 | ns | ns | ns |

| Spirochaetes | 0.91 | 0.60 | 0.92 | + | ns | + |

| Spirochaetes | 0.91 | 0.60 | 0.92 | + | ns | + |

| Spirochaetaceae | 0.88 | 0.58 | 0.90 | ns | ns | + |

| Fibrobacteres | 0.95 | 0.55 | 0.43 | ns | ns | ns |

| Fibrobacteria | 0.95 | 0.55 | 0.43 | ns | ns | ns |

| Fibrobacteraceae | 0.95 | 0.55 | 0.43 | ns | ns | ns |

| Fibrobacter | 0.95 | 0.55 | 0.43 | ns | ns | ns |

HF = high-forage diet; HC = high-concentrate diet; HCN = HC + niacin diet.

P1 = HC vs. HF; P2 = HCN vs. HF; P3 = HC vs. HCN; “ns” means P > 0.1; “+” means P < 0.1; “*” means P < 0.05; “**” means P < 0.01.

At the genera level (Table 3), HC increased the percentage of Prevotella (P < 0.05), and decreased the proportions of Paraprevotella (P < 0.01), Ruminococcus (P < 0.05), Treponema (P < 0.05), Sporobacter (P < 0.05) and Lachnospiracea incertae sedis (P < 0.1) compared with HF. In HCN group, the percentage of Succiniclasticum was higher (P < 0.1), and the proportions of Paraprevotella (P < 0.01), Ruminococcus (P < 0.05), Anaerovorax (P < 0.05), Sporobacter (P < 0.05) and L. incertae sedis (P < 0.1) were lower than those in HF. Compared with HC group, HCN group increased the percentage of Succiniclasticum, Paraprevotella, Acetivibrio and Treponema (P < 0.1), and decreased the proportions of Prevotella and Anaerovorax (P < 0.1).

4. Discussion

It was observed the duration time of ruminal pH less than 5.8 were about 12 h in HC group. Thus, based on the indication of SARA defined by Kleen and Cannizzo (2012), we considered the SARA occurred in the cattle fed HC in this study. Some researchers reported that niacin supplementation could alleviate ruminal acidosis by inhibiting the proliferation of Streptococcus bovis, producing more NAD+ to inhibit the activity of lactate dehydrogenase resulting in reducing lactic acid production (Yang et al., 2013, Zhang et al., 2014). In our study, adding niacin shortened the duration time of lower pH for HC.

The diversity of ruminal bacteria should be reduced in HC (Zened et al., 2013). In our study, HC group had lower OTU and Shannon index than HF group. The Shannon index of HCN group was higher than that of HC group, but lower than that of HF group. It was suggested niacin supplementation could increase ruminal bacterial diversity caused by HC, for its nutritional functions of bacteria that could not produce niacin.

Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes and Proteobacteria were the dominant phyla in cattle whatever the diet was. And, the effects of HC on the composition of ruminal bacterial at phylum lever were found in our study. Bacteroidetes, a kind of gram-negative bacteria contributing to the degradation of protein and polysaccharides, increased as the proportion of concentrate increased in the diet, as a same result of the studies of Fernando et al. (2010) and Petri et al. (2013). In contrast, Mao et al. (2013) reported a decreased percentage of Bacteroidetes in the Holstein suffered from SARA (sampled on day 21). One reason maybe was that the increasing Bacteroidetes promoted the glycolysis of carbohydrate, and produced more VFA, resulting in the decrease of ruminal pH, which could accelerate the death and dissolution of gram-negative bacteria. Therefore, the growth trend of Bacteroidetes always was found at the beginning of fermentation (Tajima et al., 2001). At the genus level, some studies of lactating cow revealed that the numbers of Prevotella, a major amylolytic genus (Huws et al., 2011), increased significantly during mildly grain-induced SARA (Tajima et al., 2001, Khafipour et al., 2009). In this study, the percentage of Prevotella increased in the cattle fed HC. Many researchers reported that an excess of grain introduced into the rumen caused the cellulolytic bacteria to decrease greatly (Hungate et al., 1952, Petri et al., 2013, Mao et al., 2013). In our study, we also observed a decrease in the percentage of Ruminococcus, a major cellulolytic genus (Bryant and Small, 1956), and Treponema, a genus involved in the degradation of soluble fibers (Bekele et al., 2011). And, the Paraprevotella was significantly and negatively affected by HC. Paraprevotella had been firstly identified in human's faeces and produced succinic and acetic acids as end products of glucose metabolism (Morotomi et al., 2009).

Besides, our results revealed that the addition of niacin had a positive effect on Proteobacteria, but had no effects on Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes phyla compared with HC. We also observed that the addition of niacin tended to decrease the abundance of Prevotella significantly, suggesting less degradation of starch in HF. Succiniclasticum was fairly common in the ruminal bacterial community. Van Gylswyk (1995) detected Succiniclasticum fermenting succinic acid to propionate. Niacin tended to increase the relative abundance of Succiniclasticum, which would suggest that the addition of niacin tended to promote the accumulation of propionic acid in HC. The addition of niacin also had positive effects on some minor or poorly known genera (such as Acetivibrio and Treponema), but had no effect on main cellulolytic genus (such as Ruminococcus, Butyrivibrio and Fibrobacter), which was consistent with the results of Pinloche et al. (2013) about probiotic yeast addition. Treponema was a commonly detected bacterial group in the rumen that was conductive to in the degradation of soluble fibers (Bekele et al., 2011). It was reported that most of cellulolytic genus was attached to the chyme and had less number in the rumen fluid (Feng, 2006). Thus, the difference in cellulolytic genus caused by niacin was not found in our study. In addition, the addition of niacin tended to increase the abundance of Acetivibrio, a mesophilic, gram-positive bacterium, known for its efficient degradation of crystalline cellulose (Saddler and Khan, 1981, Xu et al., 2003, Bareket et al., 2012).

5. Conclusions

This study provided the detailed account of the effects of HC and the niacin supplementation on ruminal microbe. Bacterial profile was primarily predominated by Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes and Proteobacteria in Jinjiang cattle whatever the diet was. The SARA caused by HC in the cattle was observed. High-concentrate diet supplemented with or without niacin significantly decreased effects on the α-diversity of ruminal microbial community. High-concentrate diet significantly increased the abundance of starch utilizing bacteria (like Prevotella), and decreased the abundance of Paraprevotella, Sporobacter and some fibrolytic bacteria (such as Ruminococcus and Treponema). And, the addition of niacin tended to reverse the symptoms of SARA in terms of inhibiting starch utilizing and stimulating fibrolytic degradation by decreasing the percentage of Prevotella, and increased the abundance of Succiniclasticum, Acetivibrio and Treponema.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (31260561, 31560648) and Special Fund for Agro-scientific Research in the Public Interest (201303143).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

References

- Bareket D., Ilya B., Raphael L., Bernard H., Pedro C., Hemme C.L. Genome-wide analysis of Acetivibrio cellulolyticus provides a blueprint of an elaborate cellulosome system. BMC Genomics. 2012;13(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekele A.Z., Koike S., Kobayashi Y. Phylogenetic diversity and dietary association of rumen Treponema revealed using group-specific 16S rRNA gene-based analysis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2011;316(1):51–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant M.P., Small N. Characteristics of two new genera of anaerobic curved rods isolated from the rumen of cattle. J Bacteriol. 1956;72(1):22–26. doi: 10.1128/jb.72.1.22-26.1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doreau M., Ottou J.F. Influence of niacin supplementation on in vivo digestibility and ruminal digestion in dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 1996;79(12):2247–2254. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(96)76601-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drackley J.K., Lacount D.W., Elliott J.P., Klusmeyer T.H., Overton T.R., Clark J.H. Supplemental fat and nicotinic acid for Holstein cows during an entire lactation. J Dairy Sci. 1998;81(1):201–214. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(98)75567-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y.L. 1th ed. CN; Beijing: 2006. Ruminant nutrition. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando S.C., Purvis H.T., Najar F.Z., Sukharnikov L.O., Krehbiel C.R., Nagaraja T.G. Rumen microbial population dynamics during adaptation to a high-grain diet. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76(22):7482–7490. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00388-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goad D.W., Goad C.L., Nagaraja T.G. Ruminal microbial and fermentative changes associated with experimentally induced subacute acidosis in steers. J Anim Sci. 1998;76(76):234–241. doi: 10.2527/1998.761234x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han H.Q., Liu D.C., Gao M., Hu H.L., Xie C.X., Deng W.K. Effects of different dietary NFC/NDF rations on ruminal microorganisms and pH in dairy goats. Anim Nutr. 2011;23(4):597–603. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- Hungate R.E., Dougherty R.W., Bryant M.P., Cello R.M. Microbiological and physiological changes associated with acute indigestion in sheep. Cornell Vet. 1952;42(4):423–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huws S.A., Kim E.J., Lee M.R., Scott M.B., Tweed J.K., Pinloche E. As yet uncultured bacteria phylogenetically classified as Prevotella, Lachnospiraceae, incertae sedis and unclassified Bacteroidales, Clostridiales, and Ruminococcaceae, may play a predominant role in ruminal biohydrogenation. Environ Microbiol. 2011;13(6):1500–1512. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khafipour E., Li S., Plaizier J.C., Krause D.O. Rumen microbiome composition determined using two nutritional models of subacute ruminal acidosis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75(22):7115–7124. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00739-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M., Morrison M., Yu Z. Phylogenetic diversity of bacterial communities in bovine rumen as affected by diets and microenvironments. Folia Microbiol. 2011;56(5):453–458. doi: 10.1007/s12223-011-0066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleen J.L., Cannizzo C. Incidence, prevalence and impact of SARA in dairy herds. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2012;172(1–2):4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Larue R., Yu Z., Parisi V.A., Egan A.R., Morrison M. Novel microbial diversity adherent to plant biomass in the herbivore gastrointestinal tract, as revealed by ribosomal intergenic spacer analysis and rrs gene sequencing. Environ Microbiol. 2005;7(4):530–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao S.Y., Zhang R.Y., Wang D.S., Zhu W.Y. Impact of subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA) adaptation on rumen microbiota in dairy cattle using pyrosequencing. Anaerobe. 2013;24(12):12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morotomi M., Nagai F., Sakon H. Paraprevotella clara gen. nov., sp. nov. and Paraprevotella xylaniphila sp. nov., members of the family ‘Prevotellaceae’ isolated from human faeces. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2009;59(8):1895–1900. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.008169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niehoff I.D., Hüther L., Lebzien P. Niacin for dairy cattle: a review. Brit J Nutr. 2009;101(1):5–19. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508043377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petri R.M., Schwaiger T., Penner G.B., Beauchemin K.A., Forster R.J., Mckinnon J.J. Characterization of the core rumen microbiome in cattle during transition from forage to concentrate as well as during and after an acidotic challenge. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4):1495–1499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinloche E., Mcewan N., Marden J.P., Bayourthe C., Auclair E., Newbold C.J. The effects of a probiotic yeast on the bacterial diversity and population structure in the rumen of cattle. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7):1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saddler J.N., Khan A.W. Cellulolytic enzyme system of Acetivibrio cellulolyticus. Can J Microbiol. 1981;27(3):288–294. doi: 10.1139/m81-045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields D.R., Schaefer D.M., Perry T.W. Influence of niacin supplementation and nitrogen-source on rumen microbial fermentation. J Anim Sci. 1983;57(6):1576–1583. [Google Scholar]

- Tajima K., Aminov R.I., Nagamine T., Matsui H., Nakamura M., Benno Y. Diet-dependent shifts in the bacterial population of the rumen revealed with real-time PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67(6):2766–2774. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.6.2766-2774.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gylswyk N.O. Succiniclasticum ruminis gen nov., sp nov., a ruminal bacterium converting succinate to propionate as the sole energy-yielding mechanism. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45(2):297–300. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-2-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.H., Lu D.X., Feng Z.C., Ling S.L. Effects of niacin supplementation on rumen fermentation in sheep fed a corn-soybean meal based diet by in vitro technique. Anim Nutr. 2002;14(3):60–64. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- Welkie D.G., Stevenson D.M., Weimer P.J. ARISA analysis of ruminal bacterial community dynamics in lactating dairy cows during the feeding cycle. Anaerobe. 2010;16(2):94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q., Gao W., Ding S.Y., Kenig R., Shoham Y., Bayer E.A. The cellulosome system of Acetivibrio cellulolyticus includes a novel type of adaptor protein and a cell surface anchoring protein. J Bacteriol. 2003;185(15):4548–4557. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.15.4548-4557.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Qu M.R., Ouyang K.H., Zhao X.H., Yi Z.H., Song X.Z. Effects of nicotinic acid on lactate and volatile fatty acid concentrations, and related enzyme activities in rumen of Jinjiang cattle. Anim Nutr. 2013;25(7):1610–1616. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- Zened A., Combes S., Cauquil L., Mariette J., Klopp C., Bouchez O. Microbial ecology of the rumen evaluated by 454 GS FLX pyrosequencing is affected by starch and oil supplementation of diets. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2013;83(2):504–514. doi: 10.1111/1574-6941.12011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.P., Yuan Z.R. The development state and prospect of high-grade beef market in China. Anim Nutr. 2012;48(4):34–37. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Qu M.R., Ouyang K.H., Xiong X.W., Pan K., Wen Q. Effects of niacotinic acid on lactic acid fermentation of Streptococcus bovis by an in vitro method. Anim Nutr. 2014;26(9):2623–2629. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]