Abstract

In the search for improved symptomatic treatment options for neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric diseases, muscarinic acetylcholine M1 receptors (M1 mAChRs) have received significant attention. Drug development efforts have identified a number of novel ligands, some of which have advanced to the clinic. However, a significant issue for progressing these therapeutics is the lack of robust, translatable, and validated biomarkers. One valuable approach to assessing target engagement is to use positron emission tomography (PET) tracers. In this study we describe the pharmacological characterization of a selective M1 agonist amenable for in vivo tracer studies. We used a novel direct binding assay to identify nonradiolabeled ligands, including LSN3172176, with the favorable characteristics required for a PET tracer. In vitro functional and radioligand binding experiments revealed that LSN3172176 was a potent partial agonist (EC50 2.4–7.0 nM, Emax 43%–73%), displaying binding selectivity for M1 mAChRs (Kd = 1.5 nM) that was conserved across species (native tissue Kd = 1.02, 2.66, 8, and 1.03 at mouse, rat, monkey, and human, respectively). Overall selectivity of LSN3172176 appeared to be a product of potency and stabilization of the high-affinity state of the M1 receptor, relative to other mAChR subtypes (M1 > M2, M4, M5 > M3). In vivo, use of wild-type and mAChR knockout mice further supported the M1-preferring selectivity profile of LSN3172176 for the M1 receptor (78% reduction in cortical occupancy in M1 KO mice). These findings support the development of LSN3172176 as a potential PET tracer for assessment of M1 mAChR target engagement in the clinic and to further elucidate the function of M1 mAChRs in health and disease.

Introduction

In the central nervous system, neurons that use the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) form the cholinergic system. The cortex and hippocampus are highly innervated by cholinergic projection neurons that originate in the nucleus basalis of Meynert complex. Cholinergic transmission in these forebrain regions modulates cellular excitability, synaptic plasticity, network function, and cognition (Hasselmo and Sarter, 2011; Teles-Grilo Ruivo and Mellor, 2013; Ballinger et al., 2016). In Alzheimer disease (AD), in addition to the hallmarks of amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and memory loss, there is a loss of cholinergic input to forebrain regions and reduced cholinergic transmission (Douchamps and Mathis, 2017). Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors, the most broadly used treatments for AD, inhibit the enzyme responsible for the breakdown of ACh, acting to ameliorate the ACh deficit, thereby providing cognitive benefit (Tan et al., 2014). The extent of AChE inhibition has been shown to correlate to improvements in cognition (Rogers and Friedhoff, 1996; Bohnen et al., 2005); however, studies using [11C]PMP AChE positron emission tomography (PET) to assess in vivo cortical AChE activity in subjects with AD report modest inhibition (22%–27%) at clinically used doses of the AchE inhibitor donepezil (Kuhl et al., 2000; Bohnen et al., 2005), suggesting it should be possible to boost central cholinergic transmission further. Although a higher dose of donepezil (23 mg) has been developed and marketed (Cummings et al., 2013), it is associated with significant adverse events (donepezil prescribing information), hence other approaches to more selectively modulate the cholinergic system are of considerable interest as a way to improve the benefit-to-risk profile (Tan et al., 2014; Felder et al., 2018).

ACh mediates its effects through activation of two classes of ACh receptors, muscarinic (mAChR) and nicotinic receptors. Clinical data clearly demonstrates mAChRs are important targets mediating procognitive effects of ACh. First, nonselective mAChR antagonists promote cognitive deficits in man (Rasmusson and Dudar, 1979; Robbins et al., 1997; Potter et al., 2000), whereas the direct-acting nonselective mAChR agonist xanomeline provided some evidence of cognitive benefit in patients with AD (Bodick et al., 1997; Veroff et al., 1998). mAChRs are G protein-coupled receptors and of the five isoforms identified (M1–5), M1 mAChRs are the most abundant in regions relevant for cognition (Levey et al., 1991; Wei et al., 1994; Flynn et al., 1995; Oki et al., 2005). Use of selective pharmacological tools and M1 knockout (KO) mice has revealed that M1 modulates neuronal signaling and excitability, synaptic transmission, and network function, and exerts procognitive effects (e.g., Anagnostaras et al., 2003; Shirey et al., 2009; Uslaner et al., 2013; Lange et al., 2015; Puri et al., 2015; Vardigan et al., 2015; Butcher et al., 2016; Dennis et al., 2016; Betterton et al., 2017). Importantly, M1 expression and function is conserved in postmortem human AD frontal cortex (Overk et al., 2010; Bradley et al., 2017).

One of the most significant issues with advancing a therapeutic for treatment of cognitive deficit in AD is the lack of robust, translatable, and validated biomarkers. The gold standard for assessing target engagement is to use PET tracers (Zhang and Villalobos, 2017); however, to date there has been no reported use of a PET tracer to guide clinical dose-setting for mAChR therapies, particularly for agonist ligands. Several companies have reported incorporation of pharmacodynamic biomarkers including reversal of scopolamine or nicotine abstinence-induced memory deficits or electroencephalography (EEG)-related measures (Nathan et al., 2013; https://www.heptares.com/news/261/74/Heptares-Announces-Positive-Results-from-Phase-1b-Clinical-Trial-with-HTL9936-a-First-In-Class-Selective-Muscarinic-M1-Receptor-Agonist-for-Improving-Cognition-in-Dementia-and-Schizophrenia.html; Voss et al., 2016). Concurrent use of target engagement and pharmacodynamic biomarkers would enable a more thorough exploration of the optimal relationship between target engagement and relevant cognitive endpoints or pharmacodynamic measures.

Some PET and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) tracers for muscarinic receptors have been reported; however, for the most part they are limited by low binding potentials, poor kinetic profiles, or a lack of selectivity, e.g., [11C]scopolamine, [11C]NMPB, [N-11C-methyl]-benztropine, [11C]QNB (Vora et al., 1983; Dewey et al., 1990; Varastet et al., 1992; Mulholland et al., 1995; Mcpherson, 2001; Zubieta et al., 2001). 123I-iododexetimide (123I-IDEX) has been used to image mAChRs in vivo with SPECT (Wilson et al., 1989; Müller-Gärtner et al., 1992; Boundy et al., 1995). In vitro, IDEX is a nonselective mAChR antagonist, but in vivo it measures, primarily, M1 receptor occupancy owing to the high expression of M1 mAChRs relative to other subtypes in the hippocampus and cortex. (Bakker et al., 2015). This in vivo selectivity in rodent brain probably reflects in part the high expression of M1 relative to other mAChRs in hippocampus and cortex (Oki et al., 2005), and this binding distribution is mirrored in clinical studies with 123I-IDEX (Wilson et al., 1989; Müller-Gärtner et al., 1992; Boundy et al., 1995). 123I-IDEX has been used to assess mAChR availability in olanzapine- and risperidone-treated subjects (Lavalaye et al., 2001) and for investigation of mAChR involvement in temporal lobe epilepsy (Mohamed et al., 2005). However, as IDEX and the aforementioned ligands are antagonists, they will bind to the total pool of mAChRs and will not distinguish between activated or uncoupled inactive receptors. Few G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) agonist PET ligands are available, and while a nonselective mAChR agonist, xanomeline, and an M1 allosteric agonist, GSK-1034702, have both been carbon-labeled and evaluated clinically by PET, little specific CNS binding was observed with either ligand, despite clear brain penetration (Farde et al., 1996; Ridler et al., 2014). [11C]AF150(S) is another reported agonist PET ligand for M1 receptors that has been evaluated in rats (Buiter et al., 2013). AF150(S) is structurally related to cevimeline, a rigid analog of ACh. More recently, we have reported development of novel M1 agonist PET ligands (Jesudason et al., 2017; Nabulsi et al., 2017) that should greatly facilitate evaluation of direct target engagement and inform dose setting, ultimately providing a more definitive means of testing the M1 agonist hypothesis in the clinic. Herein, we report the detailed in vitro and ex vivo characterization of one of these ligands, LSN3172176.

Methods and Materials

LSN3172176 was prepared by Eli Lilly and Company (Lilly Research Centre, Windlesham, UK). [3H]LSN3172176 (specific activity 1.295 TBq/mmol) was synthesized by Quotient Bioscience, Cardiff, UK. For occupancy experiments, male Harlan Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN, ranging from 200 to 300 g in weight). Male C57Bl6J mice were purchased from Taconic Biosciences (ranging from 15 to 34 g in weight; Germantown, NY). Muscarinic KO animals were also purchased from Taconic Biosciences: M1 (line#1784), M2 (line#1454), M3 (line#1455), M4 (line#1456), and M5 (line#1457), weight range 15–47 g. All animals experiments were carried out in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as adopted and promulgated by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, and were approved by the institution’s Animal Care and Use Committee. 3H-n-methylscopolamine ([3H]NMS; specific activity 3.16 TBq/mmol) and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell membranes expressing human M1–M5 mAChR were obtained from PerkinElmer (Boston, MA).

Nonradiolabeled Compound Direct Binding Experiments

Filter Binding Conditions.

For binding assays, recombinant human M1 membranes were incubated with compounds at 22°C for indicated times in 0.5 ml assay volume of buffer composed of: 20 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, and 10 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5. Assays were stopped by filtration over glass fiber filters (Filtermat A, GF/C; PerkinElmer), which were previously soaked in 0.5% polyethylenimine (PEI), and washed by addition of cold Tris-buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4) using a Harvester 96 (Tomtec Life Sciences, Hamden, CT). Nonspecific binding was defined with 10 μM atropine. Protein concentrations were determined using Coomasie Plus (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) with bovine serum albumin as a standard. After filtration, the samples from each well area were excised from the Filtermat sheet, and the sections placed into 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes for processing for liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC/MS) analysis.

Extraction and LC/MS Sample Prep.

Each sample was incubated with 0.5 ml of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade methanol at room temperature for 30–60 minutes. To maximize sample extraction and solubilization each GF/C filter was homogenized with a probe-tip ultrasonic dismembrator (Fisher Scientific model 100; Pittsburgh, PA) at low-to-medium power setting until slurry of even consistency was obtained (10–20 seconds). Samples were clarified by centrifugation at 16,000g for 20 minutes at room temp, then transferred to a glass HPLC sampler vial containing water to bring the final methanol content for all samples to 25%. LC/MS/MS triple quadrupole mass spectrometer detection was carried out with a Shimadzu Prominence uHPLC system where 10-μl samples were injected by autosampler onto a Zorbax SB-C18 column (Agilent Technologies, Wilmington, DE), 3.5 μm, 2.1 mm × 50 mm, maintained at 30°C. A universal 3-minute gradient elution profile was applied for all samples using a mobile phase composition ranging from 10% acetonitrile + 0.1% formic acid to 90% acetonitrile + 0.1% formic acid, pH 3. The LC was coupled to an AB Sciex 5500 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer where the ligands were detected using multiple reaction monitoring methods that monitor the transition from precursor to product ion with mass-to-charge ratios (m/z) and elute from the column with a characteristic retention time. Samples were quantified by comparing area under the peak to a standard curve generated by extracting a series of target samples processed as described above to which known quantities of ligand ranging from 0.01 to 10 ng/ml were prepared in the appropriate matrix. Reported tracer levels are expressed in units of nanograms per milliliter of cell extract. GraphPad Prism (version 6.0; GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA) software was employed for calculations, curve fitting, and graphics. All points on graphs represent the mean ± S.E.M. The number of samples per point is three to four.

In Vitro Radioligand Binding Experiments

Competition Binding.

To investigate binding selectivity, the affinity of LSN3172176 was examined across mAChR subtypes M1–M5. All experiments were performed in assay buffer of the following composition: 20 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, and 10 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5; and used 10 μg of protein/well in a total assay volume of 1 ml using deep well blocks. CHO cell membranes overexpressing human mAChR M1–M5 subtypes were incubated with a concentration of [3H]NMS that was close to the calculated Kd for each receptor (M1 200 pM, Kd = 196 pM; M2 700 pM, Kd = 769 pM; M3 700 pM, Kd = 642 pM; M4 200 pM, Kd 142 pM; M5 400 pM, Kd = 410 pM), in the presence or absence of 11 different concentrations of compound. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 10 μM atropine. All assay incubations were initiated by the addition of membrane suspensions, and deep well blocks were shaken for 5 minutes to ensure complete mixing. Incubation was then carried out for 2 hours at 21°C. Binding reactions were terminated by rapid filtration through GF/A filters (PerkinElmer) presoaked with 0.5% w/v PEI for 1 hour. Filters were then washed three times with 1 ml ice-cold assay buffer. Dried filters were counted with Meltilex A scintillant using a Trilux 1450 scintillation counter (PerkinElmer). The specific bound counts (disintegrations per minute) were expressed as a percentage of the maximal binding observed in the absence of test compound (total) and nonspecific binding determined in the presence of 10 μM atropine. Data analysis was accomplished using Excel and GraphPad Prism 7. The concentration–effect data were curve-fit using GraphPad Prism 7 to derive the potency (IC50) of the test compound. The equilibrium inhibition constant (Ki) of the test compound was then calculated by the Cheng-Prusoff equation: Ki = IC50/[1 + ([L]/Kd)] (Cheng and Prusoff, 1973).

Saturation Binding.

To further investigate selectivity, saturation experiments were performed using [3H]NMS or [3H]LSN3172176 across mAChR subtypes M1–M5. All experiments were performed in assay buffer of the following composition: 20 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl and 10 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5; and used 20 μg of protein or 10 μg ([3H]NMS)/well in a total assay volume of 1 ml using deep well blocks. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 10 μM atropine. All assay incubations were initiated by the addition of membrane suspensions, and deep well blocks were shaken for 5 minutes to ensure complete mixing. Incubation was then carried out for 2 hours at 21°C. Binding reactions were terminated by rapid filtration through GF/A filters (PerkinElmer) presoaked with 0.5% w/v PEI for 1 hour. Filters were then washed three times with 1 ml ice-cold assay buffer. Dried filters were counted with Meltilex A scintillant using a Trilux 1450 scintillation counter (PerkinElmer). The specific bound counts (disintegrations per minute) were expressed as femtomole radioligand bound per milligram protein. Data analysis was accomplished using Excel and GraphPad Prism 7. The concentration-effect data were curve-fit using GraphPad Prism 7 to derive the KD and Bmax.

Kinetic Binding.

All experiments were performed in assay buffer of the following composition: 20 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl and 10 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5; and used 20 μg of protein/well in a total assay volume of 1000 μl using deep well blocks. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 10 μM atropine. For association experiments, buffer incubations were initiated at each time point by addition of membrane suspensions to buffer containing 2 nM [3H]LSN3172176 with nonspecific binding determined in the presence of 10 μM atropine. For dissociation experiments, radioligand (same concentration as above) and membrane were incubated for 2 hours prior to addition of 10 μM atropine at the indicated time points. Binding reactions were terminated by rapid filtration through GF/A filters (PerkinElmer) that were presoaked with 0.5% w/v PEI for 1 hour. Filters were then washed three times with 1 ml ice-cold assay buffer. Dried filters were counted with Meltilex A scintillant using a Trilux 1450 scintillation counter (PerkinElmer). Data were fit to association and dissociation curves to obtain kinetic parameters (Kon, Koff, t1/2).

Native Tissue GTPγ[35S] Binding Assays.

GTPγ[35S] binding in human, rat, and mouse membranes was determined in triplicate using an antibody capture technique in 96-well plate format (DeLapp et al., 1999). Membrane aliquots (15 μg/well) were incubated with test compound and GTPγ [35S] (500 pM/well) for 30 minutes. Labeled membranes were then solubilized with 0.27% Nonidet P-40 plus Gqα antibody (E17; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) at a final dilution of 1:200 and 1.25 mg/well of anti-rabbit scintillation proximity beads. Plates were left to incubate for 3 hours and then centrifuged for 10 minutes at 2000 rpm. Plates were counted for 1 minute/well using a Wallac MicroBeta TriLux scintillation counter (PerkinElmer). All incubations took place at room temperature in GTP-binding assay buffer of the following composition: 20 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, and 5 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5. Data were converted to percentage response compared with oxotremorine M (100 μM) or percentage over basal and EC50 values generated (four parameter-logistic curve) using GraphPad Prism 6.

[3H]LSN3172176 Autoradiography Assays.

All experiments were performed in assay buffer of the following composition: 20 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, pH 7.4. [3H]LSN3172176 was used at a final concentration of 5 nM, with atropine (10 μM) used to define nonspecific binding. Wild-type, M1 KO, and M4 KO mice were received from Taconic Biosciences and sacrificed following a 1 week acclimation. Mice were decapitated and brains were removed, quick frozen in isopentane on dry ice, then stored at −80°C. On the day of sectioning, frozen tissue was mounted on cryostat chucks and equilibrated to cryostat temperature (chamber temperature ∼–20°C, object temperature ∼−16°C). Frozen sections (20 μm) were cut and thaw-mounted on Fisher SuperFrost Plus 1 inch × 3 inch slides. Sections were allowed to dry at room temperature, then stored frozen at −80°C in sealed plastic. On the day of experiment, slide-mounted tissue sections were thawed to room temperature before removal from sealed containers, preincubated at room temperature in assay buffer for 15 minutes to remove endogenous receptor ligands, then dried completely under a stream of cool air. Sections were incubated for 120 minutes on ice in assay buffer containing radioligand with or without cold displacer for nonspecific binding. Following incubation, the sections were rinsed twice by immersing in approximately 3× volume of ice-cold assay buffer for 90 seconds, followed by a final rinse in ice-cold purified water, then dried under a stream of warm air. Slides were attached to paper with double-sided tape and placed in film cassettes. Fuji BAS-TR2025 phosphorimaging plates were exposed to tissue sections for empirically determined duration (∼72 hours). Radioactive standards calibrated with known amounts of [3H], (ARC-0123; American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc., St. Louis, MO), were coexposed with each plate. Autoradiogram analysis was performed using a computer-assisted image analyzer (MCID Elite, 7.0; Imaging Research Inc., St. Catherines, ON). Images were colorized using the MCID software and stored as TIFF files.

Tracer Distribution in M1–M5 KO Mice by LC/MS/MS.

LSN3172176 was formulated in 25% β-cyclodextrin and a bolus intravenous injection of 10 μg/kg of LSN3172176 (dose volume of 0.5 ml/kg in rats and a dose volume of 5 ml/kg in mice) given into the lateral tail vein. Rodents were sacrificed by cervical dislocation 20 minutes following tracer administration. Cerebellum, frontal cortex, striatum, and plasma were collected from each animal. Tissues were dissected out, weighed, and placed in conical centrifuge tubes on ice. Four volumes (w/v) of acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid were added to each tube. Samples were then homogenized using an ultrasonic probe and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 20 minutes. Supernatant liquid (100 μl) was diluted by adding sterile water (300 μl) in HPLC injection vials for subsequent LC/MS/MS analysis.

LSN3172176 concentrations were measured with a model Shimadzu SIL-20AC/HT HPLC autosampler (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) linked to a Triple Quad 5500 mass spectrometer (AB SCIEX, Framingham, MA). An Agilent ZORBAX XDB-C18 column (2.1 mm × 50 mm; 3.5 μM; part no. 971700−902) was used for the HPLC. The precursor-to-product ion transition monitored was Q1 = 386.146, Q3 = 128.000. A gradient method lasting 5 minutes that consisted of mobile phase of various ratios of water (A) and acetonitrile (B) with 0.1% formic acid. The initial conditions were 90% A and 10% B, and the final conditions were 90% A, 10% B. Standards were prepared by adding known quantities of analyte to samples of brain tissue and plasma from nontreated animals and processed as described above.

Levels of LSN3172176 measured in frontal cortex and striatum (rich in muscarinic receptor expression) were taken to represent total ligand binding in a tissue. Cerebellar levels were used to represent nonspecific binding. The difference between the ligand concentration measured in the total binding region, the frontal cortex, and striatum to that measured in cerebellum represents specific binding to muscarinic receptors. The binding potential (BP), or signal to noise is calculated by taking the ratio of tracer measured in the total binding tissue (frontal cortex, striatum) divided by those measured in the nonspecific tissue (cerebellum).

Rat M1 Occupancy of Scopolamine.

The same procedures were also applied to evaluate the occupancy of scopolamine after intravenous injection in Harlan Sprague Dawley rats (ranging from 200 to 300 g in weight). The doses of scopolamine included 0.01, 0.03, 0.06, 0.1, 0.3 mg/kg and were administered 30 minutes prior to the tracer injection. A similar analytical protocol was used to determine the concentration of LSN3172176. Occupancy was calculated as previously described above.

Results

Selection of LSN3172176 as a Putative Tracer Molecule.

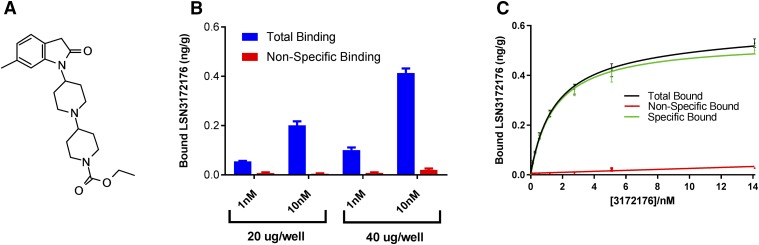

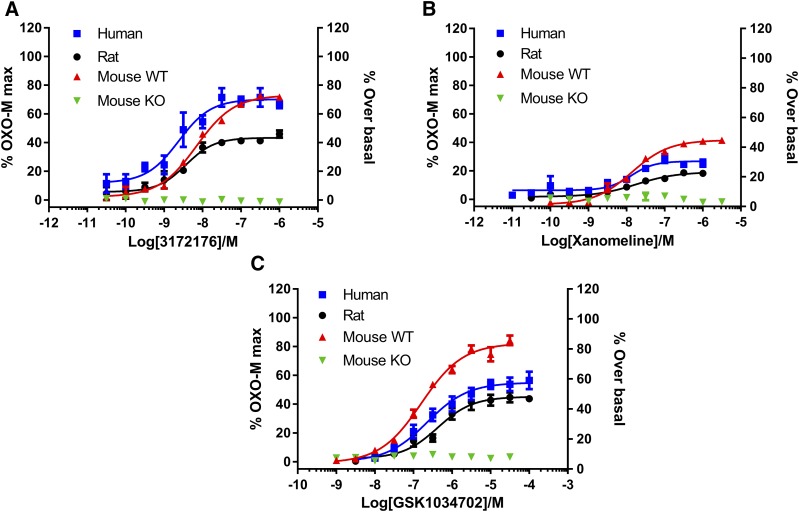

Putative tracer molecules and compounds were screened at a single concentration of 10 nM using a direct binding assay. This enabled the rapid determination of total and nonspecific binding levels for compounds in membranes containing recombinant human M1 mAChR without the expensive and time-consuming requirement to radiolabel compound. LSN3172176 (structure shown in Fig. 1A) was selected on the basis of its favorable signal (total binding)-to-noise (nonspecific binding) of 21 (Fig. 1B), in comparison with other known PET tracer molecules (5 and 7 for MDL100907 and MK4232, respectively; Table 1). Using the same assay, saturation binding was performed with LSN3172176 generating a Kd value of 1.5 nM (Fig. 1C). LSN3172176 was then assessed in vitro in a functional GTPγ [35]S binding assay utilizing native tissue from mouse, rat, and human cortex (Fig. 2). In all three species LSN3172176 was a potent, partial agonist, with EC50 values of 7.0, 3.7, and 2.4 nM in mouse, rat, and human, respectively. Efficacy values ranged from 43% to 73%. No responses were observed in cortical membranes from M1 mAChR knockout mice. Two previous mAChR PET tracer agonist ligands, Xanomeline and GSK1034702 were also assessed in this assay and displayed significantly lower potencies of between 13–17 and 160–425 nM, respectively, with both displaying partial agonist profiles. Efficacy values ranged from 19%–45% to 45%–82% for xanomeline and GSK1034702, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Initial identification of LSN3172176. A cassette of nonradiolabeled putative tracer molecules was assessed in filtration binding assays using membranes expressing the human M1 mAChR. The most promising of these compounds was (A) LSN3172176. (B) Single-point binding assay using two different concentrations of LSN3172176 (1 and 10 nM). Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 10 μM atropine (C) saturation assay from which specific binding was calculated by subtracting the mean nonspecific binding in the presence of 10 μM atropine from the mean total binding at each ligand concentration performed in triplicate and then expressed as nanograms ligand per gram protein. For both (B and C) after filtration, bound compound was extracted and measured using LC/MS/MS. Data points represent mean ± S.E.M. from three independent experiments.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of the in vitro signal-to-noise ratio of LSN3172176 binding to recombinant human M1 mAChRs vs. other known PET tracer ligands binding to their target receptors, also expressed in recombinant systems

| Target | Ligand | Membrane | [Ligand] | In Vitro Signal-to-Noise Ratio (S/N) | Human Tissue Bmax |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μg/well | /nM | fmol/mg | |||

| Human M1 | LSN3172176 | 20 | 10 | 21 | 224 (Table 4) |

| Human 5-HT2A | MDL100907 | 20 | 10 | 5 | 136 and 164 ([3H]ketanserin binding; Laruelle et al., 1993) |

| Human CGRP | MK4232 | 20 | 10 | 7 | 33.4 (Hostetler et al., 2013) |

Fig. 2.

In vitro functional profiling of LSN3172176 and comparators in native cortical tissues. Stimulation of GTPγ[35S] binding to cortical membranes prepared from human, rat, mouse, or mice deficient in the M1 receptor, in response to increasing concentrations of (A) LSN3172176, (B) xanomeline, or (C) GSK1034702. Cortical membranes were incubated at 21°C for 30 minutes with compound. Data shown are increases in GTPγ[35S] binding normalized to the response obtained with a maximally effective concentration of oxotremorine M, or for mouse M1 KO tissue the increase in binding above buffer alone. Data points represent the mean ± S.E.M. of three independent experiments each containing three to six replicates.

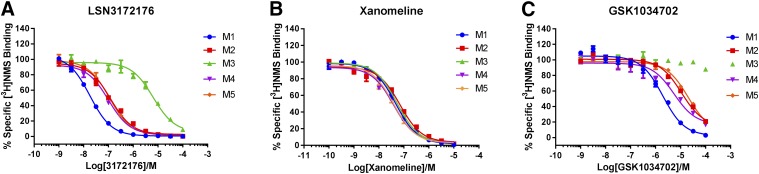

To further characterize the selectivity of LSN3172176, radioligand competition binding assays were performed using the nonselective muscarinic antagonist [3H]NMS and recombinant membranes from cells expressing human M1–M5 mAChR subtypes (Fig. 3). Results from these assays clearly demonstrated that LSN3172176 exhibited a selectivity profile favoring binding to the M1 subtype of mAChR with a rank order of Ki values of M1 > M2, M4, M5 > M3. This rank order of potency across mAChRs was similar to the results for GSK1034702; however, GSK1034702 displayed a Ki value ∼100-fold less potent than LSN3172176. In this assay, xanomeline had approximately equal affinity at all subtypes of mAChR (Table 2).

Fig. 3.

Recombinant mAChR in vitro binding profile. Displacement of [3H]NMS radioligand binding by increasing concentrations of (A) LSN3172176, (B) xanomeline, and (C) GSK1034702 across human recombinant mAChR subtypes M1–M5. Data points represent mean specific binding ± S.E.M. from three independent experiments each containing three replicates.

TABLE 2.

Summary of in vitro Ki values for displacement of 3H-NMS binding from human recombinant M1–M5 mAChRs

Ki values for LSN3172176, xanomeline, and GSK1034702 were derived from IC50 values, as described in Materials and Methods, from the data shown in Fig. 3. Values in parentheses indicate the fold-selectivity vs. the M1 mAChR.

| Compound | mAChR Subtype, Ki (nM) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | |

| LSN3172176 | 8.9 | 63.8 (7.2) | 3031 (341) | 41.4 (4.7) | 55.6 (6.2) |

| Xanomeline | 23.1 | 54.8 (2.4) | 40.0 (1.7) | 16.1 (0.7) | 26.4 (1.1) |

| GSK1034702 | 959.9 | 5674 (5.9) | 61,570 (64) | 2261 (2.4) | 10,090 (10.5) |

Characterization of [3H]LSN3172176.

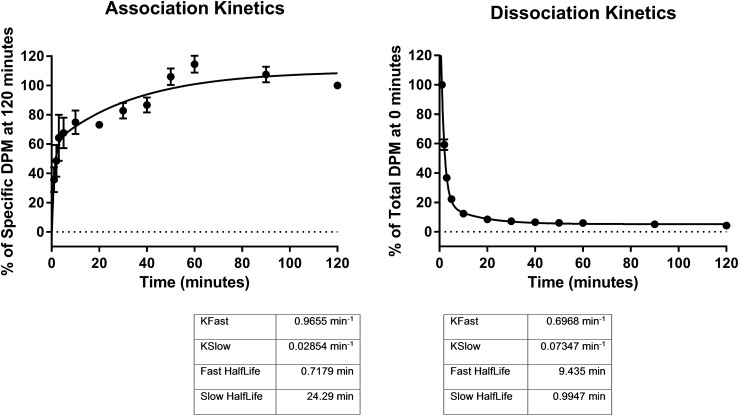

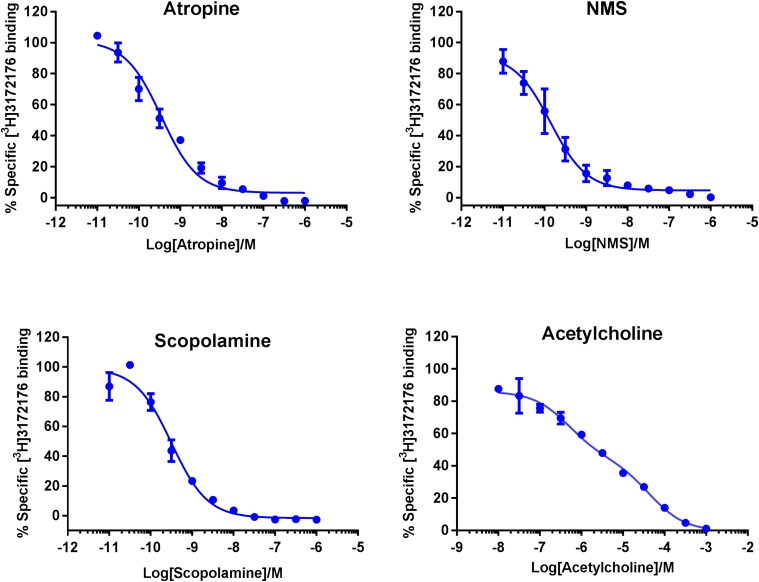

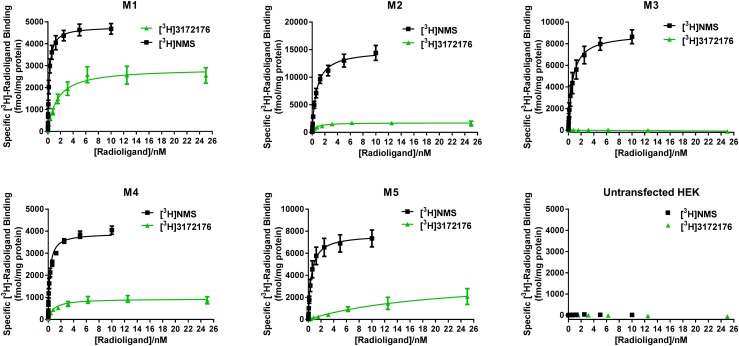

On the basis of the above results, LSN3172176 was tritiated and further experiments performed to characterize the in vitro selectivity and potency of the [3H]LSN3172176 radioligand itself. In the first instance, kinetic association and dissociation assays were performed. [3H]LSN3172176 association reached steady-state after approximately 1 hour, with dissociation kinetics revealing that [3H]LSN3172176 binding was rapidly reversible (Fig. 4). Both association and dissociation kinetic curves were best fitted to biphasic equations. The results of competition assays using membranes from cells expressing the human recombinant M1 mAChR demonstrated that binding of [3H]LSN3172176 was fully displaced by known orthosteric mAChR agonists and antagonists (Fig. 5). Full saturation binding with [3H]LSN3172176 was then performed across the five different mAChR subtypes (Fig. 6). [3H]NMS saturation binding was performed in parallel, to allow a ratio to be made between the total pool of mAChR binding sites present in the membranes and available for antagonist binding, including activated and uncoupled inactive receptors ([3H]NMS Bmax) versus the smaller pool of active receptors that is the probable target of [3H]LSN3172176 binding ([3H]3172176 Bmax) at steady-state. Although only modest differences were observed in Kd values between M1, M2, and M4 mAChRs, more substantial variations in Bmax values for [3H]LSN3172176 relative to [3H]NMS were noted, with the highest proportion of total binding observed for [3H]LSN3172176/[3H]NMS being M1 > > M4 > M2 > M5 > M3, respectively (Table 3).

Fig. 4.

[3H]LSN3172176 association and dissociation kinetics. For association rate experiments (A) specific binding was calculated by subtracting the mean nonspecific binding in the presence of 10 μM atropine from the mean total binding at each time point performed in quadruplicate. For dissociation rate experiments (B) binding was expressed as a percent of total bound DPM (disintegrations per minute) at 0 minutes. Data points represent mean ± S.E.M. from three independent experiments each containing four replicates.

Fig. 5.

Displacement of [3H]LSN3172176 by known orthosteric mAChR ligands. [3H]LSN3172176 radioligand binding (4 nM) at the human M1 recombinant mAChR was assessed in the presence of increasing concentrations of atropine, NMS, scopolamine, and acetylcholine. Data points represent mean specific binding ± S.E.M. from three independent experiments each containing three replicates.

Fig. 6.

Saturation binding profile of [3H]LSN3172176. Binding of both [3H]NMS and [3H]LSN3172176 was assessed across human M1–M5 recombinant membranes. For both ligands specific binding was calculated by subtracting the mean nonspecific binding in the presence of 10 μM atropine from the mean total binding at each radioligand concentration performed in quadruplicate and then expressed as femtomole [3H]ligand binding per milligram protein. Data points represent mean ± S.E.M. from three independent experiments. HEK, human embryonic kidney cells.

TABLE 3.

Summary of in vitro Kd and Bmax values ± S.E.M. for [3H]LSN3172176 and [3H]NMS saturation binding to human recombinant M1–M5 mAChRs

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [3H]LSN3172176 | Kd/nM | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | NSSB | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 20.5 ± 11.4 |

| Bmax | 2877 ± 175 | 1737 ± 127 | NSSB | 936 ± 61.4 | 3813 ± 1199 | |

| [3H]NMS | Kd/nM | 0.209 ± 0.025 | 0.682 ± 0.093 | 0.642 ± 0.121 | 0.242 ± 0.026 | 0.464 ± 0.093 |

| Bmax | 4786 ± 128 | 14916 ± 568 | 8959 ± 466 | 3909 ± 97.5 | 7700 ± 400 | |

| % of NMS | 60 | 12 | N/A | 24 | 50 |

NSSB, no significant saturable binding.

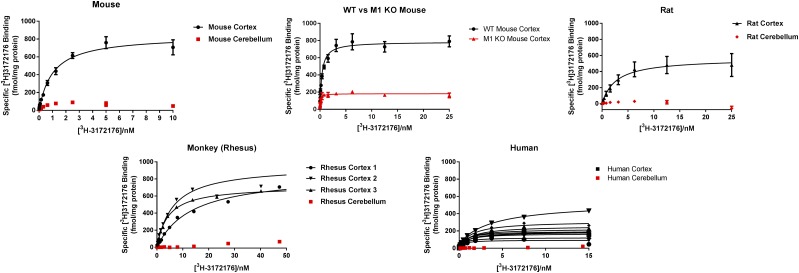

[3H]LSN3172176 Binds with High Affinity to Native Tissues.

An important aspect of tracer development is to confirm affinity across species in relevant native tissues. Therefore, saturation binding experiments were performed to assess binding of [3H]LSN3172176 using cortical and cerebellar membranes from mouse, rat, rhesus monkey, and human (Fig. 7). In cortical membranes, Kd values for [3H]LSN3172176 ranged from 1 to 8 nM, with some variability in Bmax across species (Table 4). The highest Bmax values were obtained in monkey cortical tissue and across species; little specific binding was observed to cerebellar tissue. In cortical tissue from M1 mAChR knockout mice, Bmax levels were reduced by 77%; however, some residual specific binding was observed. Binding to human cortical tissue was assessed across 10 separate donors, and whereas Kd values were consistent across individual samples, Bmax values varied considerably (Table 4).

Fig. 7.

Native tissue saturation binding. Saturation binding experiments using [3H]LSN3172176 were conducted using brain membranes (frontal cortex and cerebellum) prepared from wild-type and M1 mAChR KO mouse, rat, rhesus monkey, and human. Specific binding was calculated by subtracting the mean nonspecific binding in the presence of 10 μM atropine from the mean total binding at each radioligand concentration performed in quadruplicate and then expressed as femtomole [3H]3172176 binding per milligram protein. Data points represent mean ± S.E.M. from three independent experiments.

TABLE 4.

Summary of native tissue Kd and Bmax values for [3H]LSN3172176 binding across species and brain regions

Mean Kd and Bmax values +/− S.E.M. were calculated from data presented in Fig. 7.

| Tissue |

3H-LSN3172176 Binding to Native Tissues |

|

|---|---|---|

| Kd ± S.E.M. | Bmax ± S.E.M. Protein | |

| nM | fmol/mg protein | |

| Mouse cortex | 1.02 ± 0.15 | 839 ± 37 |

| Mouse cerebellum | NSSB | NSSB |

| M1 KO mouse | 0.1 ± 0.02 | 182 ± 6.5 |

| Rat cortex | 2.66 ± 0.89 | 562 ± 58 |

| Rat cerebellum | NSSB | NSSB |

| Rhesus cortex | 8 ± 3 | 843 ± 69 |

| Rhesus cerebellum | NSSB | NSSB |

| Human cortex | 1.03 ± 0.16 | 224 ± 35 |

| Human cerebellum | NSSB | NSSB |

NSSB, no significant saturable binding.

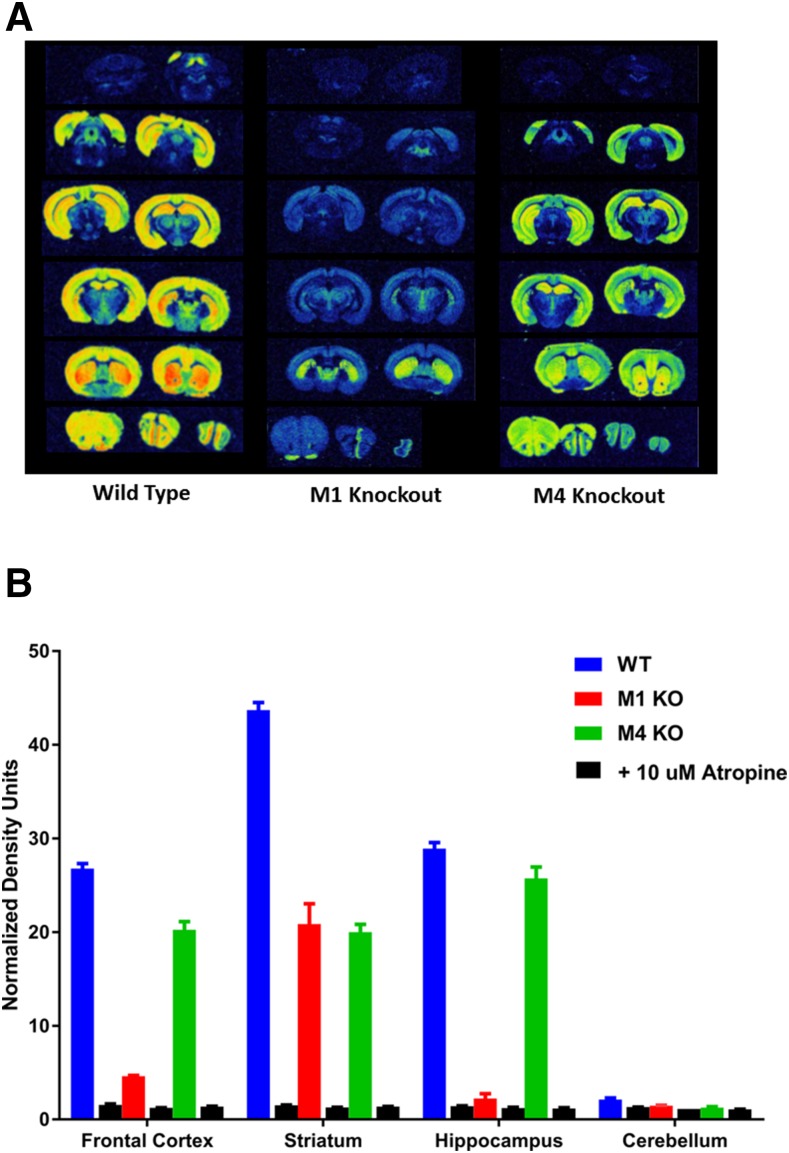

Regional Visualization of [3H]LSN3172176 Binding in the Brain by Autoradiography.

The binding of [3H]LSN3172176 was also examined by autoradiography (Fig. 8). Brain slices from wild-type and M1 or M4 mAChR knockout mice were used. Overall, high levels of binding were observed in cortical, hippocampal, and striatal regions, with binding in the hippocampal and cortical areas greatly reduced in the M1 knockout mouse but, interestingly, some residual binding remained in the striatum (Fig. 8A). Similar to results obtained with homogenates, very little binding was seen in cerebellar regions. In slices from M4 mAChR KO mice, levels of binding were only significantly reduced in the striatum. When quantified, the levels of binding that remained were comparable to those seen in homogenate binding assays (Fig. 8B) with virtually all binding displaced by the nonselective mAChR antagonist atropine.

Fig. 8.

Autoradiography with [3H]LSN3172176 in the mouse brain. (A) Binding of [3H]LSN3172176 was compared across serial fresh-frozen slices (20 μm) from wild-type or M1 or M4 KO mice. A final concentration of 5 nM [3H]LSN3172176 was used for all experiments. Representative images from a single brain are shown below. (B) Quantification of regional [3H]LSN3172176 binding was performed using brains from three separate mice from each strain. Bars reflect the average intensity of all pixels in a region of interest and represent the mean ± S.E.M. for each condition.

In Vivo Tracer Distribution and Occupancy Results.

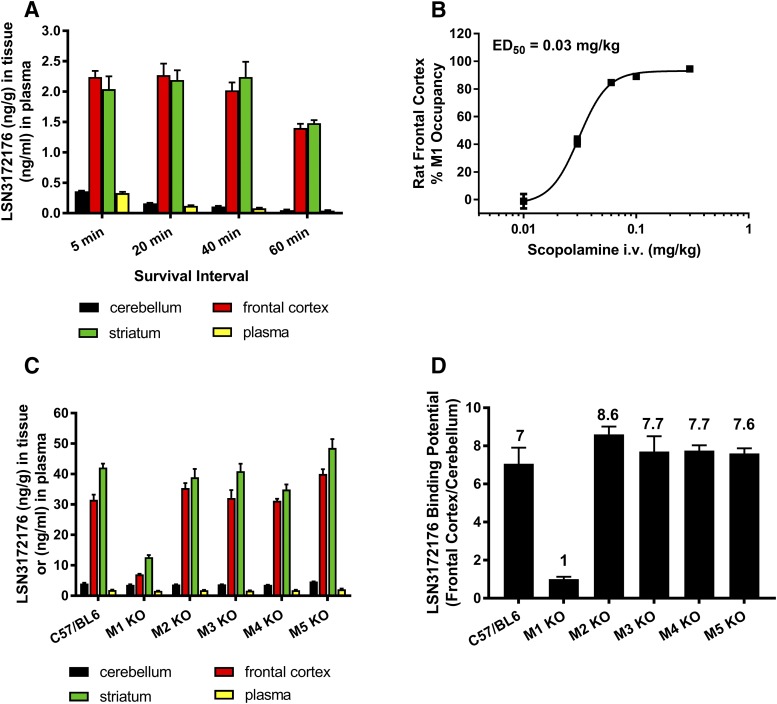

Finally, the binding of LSN3172176 to M1 receptors in vivo was evaluated in mice and rats by LC-MS/MS using a cold tracer protocol for specific binding assessment (Chernet et al., 2005). Tracer distribution, after intravenous dosing, was assessed in plasma and in brain regions known to possess high M1 mAChR levels, frontal cortex and striatum, and in cerebellum, a region low in M1 mAChRs used as a null-region. The pattern of LSN3172176 distribution that was observed, high in cortex and striatum, low in cerebellum (Fig. 9A), was consistent with known regional densities. Further work was conducted in rats to explore the utility of LSN3172176 for receptor occupancy studies. For these studies, scopolamine, a ligand shown to compete with LSN3172176 in vitro binding to the M1 orthosteric site, was administered intravenously in escalating doses (0.01, 0.03, 0.06, 0.1, 0.3 mg/kg) 30 minutes prior to tracer (LSN3172176) injection (Fig. 9B). The data shows that scopolamine dose dependently reduced tracer binding in frontal cortex, with near maximal occupancy of the M1 mAChR achieved at 0.3 mg/kg scopolamine. Additional studies were conducted to verify binding selectivity using wild-type and M1–M5 mAChR KO mice (Fig. 9C). In M1 mAChR KO mice dosed only with the tracer LSN3172176, the binding potential (the ratio of total binding in frontal cortex to nonspecific binding in cerebellum) was reduced from 7.1 to 1.0 relative to the control group of C57BLK6 mice (Fig. 9D). Binding potential values obtained from M2–M5 mAChR KO mice remained unchanged as detected by LC-MS/MS. No changes in tracer levels were observed in the total or nonspecific tissues collected. These data suggest that, in vivo, the specific binding seen in mouse frontal cortex is predominantly the result of binding to M1 mAChR. In striatum, a higher degree of residual occupancy was observed in M1 KO mice, which may correspond to a small amount of binding to M4 and possibly also M2 mAChRs, mirroring the results obtained in the autoradiography experiments (Fig. 8A). Nevertheless, the majority of binding in this region is to the M1 receptor.

Fig. 9.

In vivo distribution and occupancy of LSN3172176 in the rat and mouse. (A) Tissue distribution and plasma levels of LSN3172176 in the rat over time. Rats were dosed with 0.3 μg/kg (i.v.) of LSN 3172176 and sacrificed at the indicated intervals. The amount of LSN3172176 in each tissue was quantified by LC/MS as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Scopolamine block of LSN3172176 receptor occupancy in rat frontal cortex. Rats were predosed with 0.01–0.3 mg/kg scopolamine (i.v.) prior to administration of 0.3 μg/kg LSN3172176. After 20 minutes animals were sacrificed and the amount of LSN3172176 in each tissue quantified by LC/MS as described in the Materials and Methods (C) Tissue distribution and plasma levels of LSN3172176 in wild-type and M1–M5 mAChR KO Mice. Mice were dosed with 10 μg/kg LSN3172176. After 20 minutes animals were sacrificed and the amount of LSN3172176 in each tissue quantified by LC/MS as described in the Materials and Methods. (D) Binding potential comparisons for LSN3172176 in wild-type vs. M1–M5 mAChR KO Mice. The in vivo binding potential was calculated by dividing the amount of LSN3172176 in the frontal cortex by the amount determined in the cerebellum by LC/MS. Bars/points represent mean ± S.E.M. from n = 3–5 male mice or rats per treatment group.

Discussion

In this study, we have characterized the in vitro and in vivo properties of LSN3172176, a novel M1 mAChR agonist tracer. In vitro, LSN3172176 is a potent, partial, orthosteric agonist at recombinant and native M1 mAChRs and this profile is conserved across species. In in vitro autoradiography and in vivo cold tracer distribution studies, LSN3172176 displays a regional distribution that corresponds closely to the known regional densities of M1 mAChRs, and predominant binding to M1 was confirmed using knockout mice. In receptor occupancy studies, LSN3172176 tracer binding was fully displaceable in the presence of a competing, orthosteric, mAChR ligand. On aggregate, this data confirms that LSN3172176 binds to the M1 mAChR in the rodent brain in vivo and that it is suitable for studies of M1 mAChR occupancy. One of the hurdles in the selection and development of successful radiolabeled tracer molecules is the difficultly in predicting the levels of nonspecific and total binding for a given tracer. Radiolabeling all molecules within a defined structure-activity relationship is not only time-consuming but also extremely expensive. By employing the direct-binding technique described in this study, we were able to rapidly obtain a preliminary assessment of the in vitro binding properties for a number of possible tracer molecules and to benchmark signal-to-noise ratios and Bmax levels to those of known PET tracer ligands (Table 1). We theorized that the higher the ratio the more optimal would be the tracer ligand predicted in vitro/in vivo. To our knowledge, use of this technique in this paradigm has not previously been described, but we believe it has the potential to rapidly advance generation of potential PET tracer molecules for further preclinical evaluation.

However, obtaining a good level of signal-to-noise in vitro is only one part of the PET ligand development challenge. Historically, selectivity over the other subtypes of mAChR has been notoriously difficult to obtain owing to the highly conserved nature of the orthosteric binding site across all subtypes of muscarinic receptor (Wess et al., 2007; Ma et al., 2009). Although, LSN3172176 certainly binds to the orthosteric site both in vitro, as demonstrated by [3H]NMS displacement experiments, and in vivo through displacement by scopolamine, we believe that LSN3172176 partially extends into the allosteric binding site (unpublished data), thus providing a possible mechanism to explain its apparent selectivity over the other subtypes of mAChR. This bitopic binding motif conferring improved M1 selectivity has been previously described and is probably a feature of many GPCR ligands (Watt et al., 2011; Lane et al., 2013; Keov et al., 2014). Compared with xanomeline, LSN3172176 showed a superior selectivity for M1 mAChRs in [3H]NMS competition binding studies; however, the Kd for [3H]LSN3172176 at M1,2 and 4 mAChRs was overlapping, begging the question of why this ligand can still achieve the high degree of in vitro and in vivo selectivity for M1 mAChRs observed in the current study. As we have demonstrated through functional GTPγ[35]S binding in a variety of native tissues, LSN3172176 is a partial agonist across species and would be expected to stabilize the high affinity form of the M1 receptor. This is consistent with our findings that NMS labeled more sites relative to LSN3172176 when assessed in the same recombinant M1-5 membrane preparations. Interestingly, we found that the amount of maximal binding of the tritiated form of LSN3172176 varied widely relative to NMS binding (Bmax values) across the five mAChR subtypes, and was proportionally highest at the M1 mAChR. Although extrapolation from an overexpressing cell line to native tissues is a potential confound, we believe that this phenomenon, combined with the selectivity displayed in the [3H]NMS competition binding assays and the dominant expression of M1 mAChRs in the brain regions we studied (Supplementary Fig. 1), together probably confer the in vitro and in vivo selectivity of binding at the M1 mAChR.

With a view to clinical translation, another important aspect to confirm during development of a PET tracer molecule was high tracer affinity across species. Using relevant native tissues (cortex, cerebellum) from rodent, monkey, and human tissue, we demonstrated that LSN3172176 retained its affinity for the M1 receptor across species, with regional receptor distributions also shown to be conserved. The variability in total binding observed across individual human samples could be the result of differences within regions, variable expression levels between individuals, or possibly may reflect technical challenges of obtaining consistent quality of postmortem samples. If these levels are correct, albeit lower in human compared with other species, the M1 Bmax levels in human tissue are still higher than the Bmax levels of the CGRP or 5-HT2A receptors, the targets of the two other clinically validated PET tracers examined; hence, we do not envisage this will be an issue for PET imaging studies in man (Table 1). In the in vitro autoradiographic and in vivo tracer distribution studies, there also appeared to be a low level of LSN3172176 binding to non-M1 receptors, which was more prevalent in the striatum, a region known to contain a high density of M4 mAChR (Bymaster et al., 2003; Supplemental Fig. 1). As LSN3172176 has high affinity for M4 receptors, in all likelihood these data are the result of binding of the ligand not only to M1 but also to the M4 subtype of mAChR. A modest contribution from binding to M2 mAChR might also be plausible given the high affinity LSN3172176 displays for the mAChR subtype as well. If this tracer moves forward as a PET tracer for dose selection for selective M1 agonists, it would be important to focus not just on the region giving the highest binding (which is generally striatum from preclinical studies), but also on the regions where preclinical work suggests the signal is most dominantly contributed by M1 mAChRs (hippocampus, cortex), and where the signal is probably more completely displaceable. Overall, however, the data package supports the binding predominance of LSN3172176 M1 mAChRs across the brain regions studied. Indeed, the binding of LSN3172176 in cortex in vivo was reduced by ∼85% in M1 mAChR KO mice. Coupled with its retention of affinity in human native tissue we believe that this selectivity should translate favorably to humans. A preliminary report detailing successful carbon labeling and evaluation of [11C]LSN3172176 as a PET tracer in nonhuman primates revealed [11C]LSN3172176 possessed high brain uptake, appropriate tissue kinetics, and high specific binding (Nabulsi et al., 2017). As in our studies, scopolamine pretreatment reduced radiotracer binding, with 98.5% target occupancy achieved at 50 μg/kg, i.v. Moreover, the ED50 dose (30 μg/kg i.v). of scopolamine reversal obtained in the current study is highly relevant as this dose range is associated with disruption of attention and sensory discrimination (Klinkenberg and Blokland, 2010). From these preliminary reports, [11C]LSN3172176 appears to be superior to previously reported muscarinic PET ligands. For example, in comparison with [11C]AF150(S) (Buiter et al., 2013), LSN3172176 is more potent and displays a considerably higher binding potential in vivo in rats.

There are very few GPCR-agonist clinical PET ligands, with the notable exception of [11C]carfentanil. This agonist PET ligand has been used extensively to evaluate the role of the μ-opioid receptor in health and disease and to detect occupancy changes in response to changes in endogenous tone or administered μ-opioid drugs (Frost et al., 1985; van Waarde et al., 2014). Dopamine D2 receptor agonist PET ligands have also been reported (e.g., Otsuka et al., 2009). If the nonhuman primate PET studies with [11C]LSN3172176 successfully translate to man, this molecule should prove to be a highly valuable tool to aid dose setting for M1 ligands and for evaluation of M1 mAChRs in human health and disease.

Acknowledgments

Human tissue samples were from Randy Woltjer at the Oregon Alzheimer’s Disease Center.

Abbreviations

- ACh

acetylcholine

- AChE

acetylcholinesterase

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- [11C]AF150(S)

1-methylpiperidine-4-spiro-(2′-methylthiazoline)

- CGRP

Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- GSK-1034702

4-fluoro-6-methyl-1-(1-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-4-yl)-4-piperidinyl)-1,3-dihydro-2H-benzimidazol-2-one

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- 123I-IDEX

123I-iododexetimide

- KO

knockout

- LC/MS

liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry

- LSN3172176, ETHYL 4-(6-METHYL-2-OXO-2,3-DIHYDRO-1H-INDOL-1-YL)-1,4'-BIPIPERIDINE-1'-CARBOXYLATE; mAChR

muscarinic acetylcholine receptor

- [11C]NMPB

11C-N-methyl piperidyl benzilate

- [3H]NMS

3H-N-methylscopolamine

- PEI

poly(iminoethylene)

- PET

positron emission tomography

- [11C]PMP

1-[11C]methylpiperidin-4-yl propionate

- [11C]QNB

[11C]quinuclidinyl benzilate

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Mogg, Gehlert, Jesudason, M.P. Johnson, Felder, Barth, Broad.

Conducted experiments: Mogg, Eessalu, M. Johnson, Wright, Sanger, Xiao, Schober, Crabtree, Smith, Colvin.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Goldsmith.

Performed data analysis: Mogg, Eessalu, M. Johnson, Sanger, Wright, Barth.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Mogg, Felder, Barth, Broad.

Footnotes

The Oregon Alzheimer’s Disease Center is supported by National Institutes of Health [Grant P30AG008017]. The authors are, or have been, employees of Eli Lilly and Company. Eli Lilly does not sell any of the compounds or devices mentioned in this article.

This article has supplemental material available at jpet.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at jpet.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Anagnostaras SG, Murphy GG, Hamilton SE, Mitchell SL, Rahnama NP, Nathanson NM, Silva AJ. (2003) Selective cognitive dysfunction in acetylcholine M1 muscarinic receptor mutant mice. Nat Neurosci 6:51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker G, Vingerhoets WA, van Wieringen J-P, de Bruin K, Eersels J, de Jong J, Chahid Y, Rutten BP, DuBois S, Watson M, et al. (2015) 123I-iododexetimide preferentially binds to the muscarinic receptor subtype M1 in vivo. J Nucl Med 56:317–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballinger EC, Ananth M, Talmage DA, Role LW. (2016) Basal forebrain cholinergic circuits and signaling in cognition and cognitive decline. Neuron 91:1199–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betterton RT, Broad LM, Tsaneva-Atanasova K, Mellor JR. (2017) Acetylcholine modulates gamma frequency oscillations in the hippocampus by activation of muscarinic M1 receptors. Eur J Neurosci 45:1570–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodick NC, Offen WW, Levey AI, Cutler NR, Gauthier SG, Satlin A, Shannon HE, Tollefson GD, Rasmussen K, Bymaster FP, et al. (1997) Effects of xanomeline, a selective muscarinic receptor agonist, on cognitive function and behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 54:465–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnen NI, Kaufer DI, Hendrickson R, Ivanco LS, Lopresti BJ, Koeppe RA, Meltzer CC, Constantine G, Davis JG, Mathis CA, et al. (2005) Degree of inhibition of cortical acetylcholinesterase activity and cognitive effects by donepezil treatment in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 76:315–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boundy KL, Barnden LR, Rowe CC, Reid M, Kassiou M, Katsifis AG, Lambrecht RM. (1995) Human dosimetry and biodistribution of iodine-123-iododexetimide: a SPECT imaging agent for cholinergic muscarinic neuroreceptors. J Nucl Med 36:1332–1338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley SJ, Bourgognon J-M, Sanger HE, Verity N, Mogg AJ, White DJ, Butcher AJ, Moreno JA, Molloy C, Macedo-Hatch T, et al. (2017) M1 muscarinic allosteric modulators slow prion neurodegeneration and restore memory loss. J Clin Invest 127:487–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buiter HJ, Windhorst AD, Huisman MC, Yaqub M, Knol DL, Fisher A, Lammertsma AA, Leysen JE. (2013) [11C]AF150(S), an agonist PET ligand for M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. EJNMMI Res 3:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher AJ, Bradley SJ, Prihandoko R, Brooke SM, Mogg A, Bourgognon J-M, Macedo-Hatch T, Edwards JM, Bottrill AR, Challiss RAJ, et al. (2016) An antibody biosensor establishes the activation of the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor during learning and memory. J Biol Chem 291:8862–8875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bymaster FP, McKinzie DL, Felder CC, Wess J. (2003) Use of M1-M5 muscarinic receptor knockout mice as novel tools to delineate the physiological roles of the muscarinic cholinergic system. Neurochem Res 28:437–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Prusoff WH. (1973) Relationship between the inhibition constant (K1) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem Pharmacol 22:3099–3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernet E, Martin LJ, Li D, Need AB, Barth VN, Rash KS, Phebus LA. (2005) Use of LC/MS to assess brain tracer distribution in preclinical, in vivo receptor occupancy studies: dopamine D2, serotonin 2A and NK-1 receptors as examples. Life Sci 78:340–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JL, Geldmacher D, Farlow M, Sabbagh M, Christensen D, Betz P. (2013) High-dose donepezil (23 mg/day) for the treatment of moderate and severe Alzheimer’s disease: drug profile and clinical guidelines. CNS Neurosci Ther 19:294–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLapp NW, McKinzie JH, Sawyer BD, Vandergriff A, Falcone J, McClure D, Felder CC. (1999) Determination of [35S]guanosine-5′-O-(3-thio)triphosphate binding mediated by cholinergic muscarinic receptors in membranes from Chinese hamster ovary cells and rat striatum using an anti-G protein scintillation proximity assay. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 289:946–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis SH, Pasqui F, Colvin EM, Sanger H, Mogg AJ, Felder CC, Broad LM, Fitzjohn SM, Isaac JTR, Mellor JR. (2016) Activation of muscarinic M1 acetylcholine receptors induces long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Cereb Cortex 26:414–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey SL, MacGregor RR, Brodie JD, Bendriem B, King PT, Volkow ND, Schlyer DJ, Fowler JS, Wolf AP, Gatley SJ, et al. (1990) Mapping muscarinic receptors in human and baboon brain using [N-11C-methyl]-benztropine. Synapse 5:213–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douchamps V, Mathis C. (2017) A second wind for the cholinergic system in Alzheimer’s therapy. Behav Pharmacol 28:112–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farde L, Suhara T, Halldin C, Nybäck H, Nakashima Y, Swahn CG, Karlsson P, Ginovart N, Bymaster FP, Shannon HE, et al. (1996) PET study of the M1-agonists [11C]xanomeline and [11C]butylthio-TZTP in monkey and man. Dementia 7:187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felder CC, Goldsmith PJ, Jackson K, Sanger HE, Evans DA, Mogg AJ, Broad LM. (2018) Current status of muscarinic M1 and M4 receptors as drug targets for neurodegenerative diseases. J Neuropharmacol DOI: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.01.028 [published ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn DD, Ferrari-DiLeo G, Mash DC, Levey AI. (1995) Differential regulation of molecular subtypes of muscarinic receptors in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem 64:1888–1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost JJ, Wagner HN, Jr, Dannals RF, Ravert HT, Links JM, Wilson AA, Burns HD, Wong DF, McPherson RW, Rosenbaum AE, et al. (1985) Imaging opiate receptors in the human brain by positron tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr 9:231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo ME, Sarter M. (2011) Modes and models of forebrain cholinergic neuromodulation of cognition. Neuropsychopharmacology 36:52–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostetler ED, Joshi AD, Sanabria-Bohórquez S, Fan H, Zeng Z, Purcell M, Gantert L, Riffel K, Williams M, O’Malley S, et al. (2013) In vivo quantification of calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor occupancy by telcagepant in rhesus monkey and human brain using the positron emission tomography tracer [11C]MK-4232. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 347:478–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesudason C, Barth V, Goldsmith P, Ruley K, Johnson M, Mogg A, Colvin E, Dubois S, Broad L, Felder C, et al. (2017) Discovery of two novel, selective agonist radioligands as PET imaging agents for the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor. J Nucl Med 58:546. [Google Scholar]

- Keov P, López L, Devine SM, Valant C, Lane JR, Scammells PJ, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A. (2014) Molecular mechanisms of bitopic ligand engagement with the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor. J Biol Chem 289:23817–23837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinkenberg I, Blokland A. (2010) The validity of scopolamine as a pharmacological model for cognitive impairment: A review of animal behavioral studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 34:1307–1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl DE, Minoshima S, Frey KA, Foster NL, Kilbourn MR, Koeppe RA. (2000) Limited donepezil inhibition of acetylcholinesterase measured with positron emission tomography in living Alzheimer cerebral cortex. Ann Neurol 48:391–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane JR, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A. (2013) Bridging the gap: bitopic ligands of G-protein-coupled receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci 34:59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange HS, Cannon CE, Drott JT, Kuduk SD, Uslaner JM. (2015) The M1 muscarinic positive allosteric modulator PQCA improves performance on translatable tests of memory and attention in Rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 355:442–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham A, Casanova MF, Toti R, Weinberger DR, Kleinman JE. (1993) Selective abnormalities of prefrontal serotonergic receptors in schizophrenia. A postmortem study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 50:810–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavalaye J, Booij J, Linszen DH, Reneman L, van Royen EA. (2001) Higher occupancy of muscarinic receptors by olanzapine than risperidone in patients with schizophrenia. A[123I]-IDEX SPECT study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 156:53–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levey AI, Kitt CA, Simonds WF, Price DL, Brann MR. (1991) Identification and localization of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor proteins in brain with subtype-specific antibodies. J Neurosci 11:3218–3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Seager MA, Wittmann M, Jacobson M, Bickel D, Burno M, Jones K, Graufelds VK, Xu G, Pearson M, et al. (2009) Selective activation of the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor achieved by allosteric potentiation [published correction appears in Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2009) 106:18040]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:15950–15955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcpherson DW. (2001) Targeting cerebral muscarinic acetylcholine receptors with radioligands for diagnostic nuclear medicine studies, in Ion Channel Localization: Methods and Protocols (Lopatin AN and Nichols CG, eds) pp 17–38, Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed A, Eberl S, Fulham MJ, Kassiou M, Zaman A, Henderson D, Beveridge S, Constable C, Lo SK. (2005) Sequential 123I-iododexetimide scans in temporal lobe epilepsy: comparison with neuroimaging scans (MR imaging and 18F-FDG PET imaging). Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 32:180–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulholland GK, Kilbourn MR, Sherman P, Carey JE, Frey KA, Koeppe RA, Kuhl DE. (1995) Synthesis, in vivo biodistribution and dosimetry of [11C]N-methylpiperidyl benzilate ([11C]NMPB), a muscarinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist. Nucl Med Biol 22:13–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Gärtner HW, Wilson AA, Dannals RF, Wagner HN, Jr, Frost JJ. (1992) Imaging muscarinic cholinergic receptors in human brain in vivo with Spect, [123I]4-iododexetimide, and [123I]4-iodolevetimide. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 12:562–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabulsi N, Holden D, Zheng M-Q, Slieker L, Barth V, Lin S, Kant N, Jesudason C, Labaree D, Shirali A, et al. (2017) Evaluation of a novel, selective M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor ligand 11C-LSN3172176 in non-human primates. J Nucl Med 58:275. [Google Scholar]

- Nathan PJ, Watson J, Lund J, Davies CH, Peters G, Dodds CM, Swirski B, Lawrence P, Bentley GD, O’Neill BV, et al. (2013) The potent M1 receptor allosteric agonist GSK1034702 improves episodic memory in humans in the nicotine abstinence model of cognitive dysfunction. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 16:721–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oki T, Takagi Y, Inagaki S, Taketo MM, Manabe T, Matsui M, Yamada S. (2005) Quantitative analysis of binding parameters of [3H]N-methylscopolamine in central nervous system of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor knockout mice. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 133:6–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka T, Ito H, Halldin C, Takahashi H, Takano H, Arakawa R, Okumura M, Kodaka F, Miyoshi M, Sekine M, et al. (2009) Quantitative PET analysis of the dopamine D2 receptor agonist radioligand 11C-(R)-2-CH3O-N-n-propylnorapomorphine in the human brain. J Nucl Med 50:703–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overk CR, Felder CC, Tu Y, Schober DA, Bales KR, Wuu J, Mufson EJ. (2010) Cortical M1 receptor concentration increases without a concomitant change in function in Alzheimer’s disease. J Chem Neuroanat 40:63–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter DD, Pickles CD, Roberts RC, Rugg MD. (2000) Scopolamine impairs memory performance and reduces frontal but not parietal visual P3 amplitude. Biol Psychol 52:37–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri V, Wang X, Vardigan JD, Kuduk SD, Uslaner JM. (2015) The selective positive allosteric M1 muscarinic receptor modulator PQCA attenuates learning and memory deficits in the Tg2576 Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Behav Brain Res 287:96–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmusson DD, Dudar JD. (1979) Effect of scopolamine on maze learning performance in humans. Experientia 35:1069–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridler K, Cunningham V, Huiban M, Martarello L, Pampols-Maso S, Passchier J, Gunn RN, Searle G, Abi-Dargham A, Slifstein M, et al. (2014) An evaluation of the brain distribution of [(11)C]GSK1034702, a muscarinic-1 (M 1) positive allosteric modulator in the living human brain using positron emission tomography. EJNMMI Res 4:66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW, Semple J, Kumar R, Truman MI, Shorter J, Ferraro A, Fox B, McKay G, Matthews K. (1997) Effects of scopolamine on delayed-matching-to-sample and paired associates tests of visual memory and learning in human subjects: comparison with diazepam and implications for dementia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 134:95–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SL, Friedhoff LT, The Donepezil Study Group (1996) The efficacy and safety of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: results of a US multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Dementia 7:293–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirey JK, Brady AE, Jones PJ, Davis AA, Bridges TM, Kennedy JP, Jadhav SB, Menon UN, Xiang Z, Watson ML, et al. (2009) A selective allosteric potentiator of the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor increases activity of medial prefrontal cortical neurons and restores impairments in reversal learning. J Neurosci 29:14271–14286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan C-C, Yu J-T, Wang H-F, Tan M-S, Meng X-F, Wang C, Jiang T, Zhu X-C, Tan L. (2014) Efficacy and safety of donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and memantine for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis 41:615–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teles-Grilo Ruivo LM, Mellor JR. (2013) Cholinergic modulation of hippocampal network function. Front Synaptic Neurosci 5:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uslaner JM, Eddins D, Puri V, Cannon CE, Sutcliffe J, Chew CS, Pearson M, Vivian JA, Chang RK, Ray WJ, et al. (2013) The muscarinic M1 receptor positive allosteric modulator PQCA improves cognitive measures in rat, cynomolgus macaque, and rhesus macaque. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 225:21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Waarde A, Absalom AR, Visser AKD, Dierckx RAJO.(2014) Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging of opioid receptors, in PET and SPECT of Neurobiological Systems (Dierckx RAJO, Otte A, de Vries EFJ, van Waarde A, Luiten PGM. eds) pp 585–623, Springer, Heidelberg, Berlin. [Google Scholar]

- Varastet M, Brouillet E, Chavoix C, Prenant C, Crouzel C, Stulzaft O, Bottlaender M, Cayla J, Mazière B, Mazière M. (1992) In vivo visualization of central muscarinic receptors using [11C]quinuclidinyl benzilate and positron emission tomography in baboons. Eur J Pharmacol 213:275–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardigan JD, Cannon CE, Puri V, Dancho M, Koser A, Wittmann M, Kuduk SD, Renger JJ, Uslaner JM. (2015) Improved cognition without adverse effects: novel M1 muscarinic potentiator compares favorably to donepezil and xanomeline in rhesus monkey. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 232:1859–1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veroff AE, Bodick NC, Offen WW, Sramek JJ, Cutler NR. (1998) Efficacy of xanomeline in Alzheimer disease: cognitive improvement measured using the computerized neuropsychological test battery (CNTB). Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 12:304–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vora MM, Finn RD, Boothe TE, Liskwosky DR, Potter LT. (1983) [N-methyl-11C]-scopolamine: synthesis and distribution in rat brain. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm 20:1229–1236. [Google Scholar]

- Voss T, Li J, Cummings J, Doody R, Farlow M, Assaid C, Froman S, Leibensperger H, Snow-Adami L, McMahon KB, et al. (2016) MK7622, a positive allosteric modulator of the M1 acetylcholine receptor, does not improve symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled proof of concept trial. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 3:336–337. [Google Scholar]

- Watt ML, Schober DA, Hitchcock S, Liu B, Chesterfield AK, McKinzie D, Felder CC. (2011) Pharmacological characterization of LY593093, an M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor-selective partial orthosteric agonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 338:622–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J, Walton EA, Milici A, Buccafusco JJ. (1994) m1-m5 muscarinic receptor distribution in rat CNS by RT-PCR and HPLC. J Neurochem 63:815–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wess J, Eglen RM, Gautam D. (2007) Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors: mutant mice provide new insights for drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov 6:721–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson AA, Dannals RF, Ravert HT, Frost JJ, Wagner HNJ., Jr (1989) Synthesis and biological evaluation of [125I]- and [123I]-4-iododexetimide, a potent muscarinic cholinergic receptor antagonist. J Med Chem 32:1057–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Villalobos A. (2017) Strategies to facilitate the discovery of novel CNS PET ligands. EJNMMI Radiopharm Chem 1:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubieta JK, Koeppe RA, Frey KA, Kilbourn MR, Mangner TJ, Foster NL, Kuhl DE. (2001) Assessment of muscarinic receptor concentrations in aging and Alzheimer disease with [11C]NMPB and PET. Synapse 39:275–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]