Abstract

The present study was aimed at investigating the adverse effects of dietary zearalenone (ZEA) on the lymphocyte proliferation rate (LPR), interleukin-2 (IL-2), mRNA expressions of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and histopathologic changes of spleen in post-weanling gilts. A total of 20 crossbred piglets (Yorkshire × Landrace × Duroc) with an initial BW of 10.36 ± 1.21 kg (21 d of age) were used in the study. Piglets were fed a basal diet with an addition of 0, 1.1, 2.0, or 3.2 mg/kg purified ZEA for 18 d ad libitum. The results showed that LPR and IL-2 production of spleen decreased linearly (P < 0.05) as dietary ZEA increased. Splenic mRNA expressions of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) were linearly up-regulated (P < 0.05) as dietary ZEA increased. On the contrary, linear down-regulation (P < 0.05) of mRNA expression of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) was observed as dietary ZEA increased. Swelling splenocyte in 1.1 mg/kg ZEA treatments, atrophy of white pulp and swelling of red pulp in 2.0 and 3.2 mg/kg ZEA treatments were observed. The cytoplasmic edema in 1.1 mg/kg ZEA treatments, significant chromatin deformation in 2.0 mg/kg ZEA treatment and phagocytosis in 3.2 mg/kg ZEA treatment were observed. Results suggested that dietary ZEA at 1.1 to 3.2 mg/kg can induce splenic damages and negatively affect immune function of spleen in post-weanling gilts.

Keywords: Pro-inflammatory cytokines, Gilt, Histopathology, IL-2, Lymphocyte proliferation rate, Zearalenone

1. Introduction

Zearalenone (ZEA) is one of mycotoxins produced mainly by Fusarium fungi growing on grains and its derived products worldwide (Warth et al., 2012, Wei et al., 2012, Zinedine et al., 2007). Among farm animals, pigs, especially female pigs are susceptible to ZEA (EC, 2006), resulted in maximum limits of 0.1 mg ZEA/kg diet for piglets and gilts (EFSA, 2004).

The major toxicity of ZEA and its metabolites, such as α-zearalonol (α-ZOL), is attributed to their estrogenic effects on the genital organs and reproduction in gilts (Etienne and Jemmali, 1982, Jiang et al., 2010). Besides, ZEA has been shown to be toxic to multiple tissues in animals, such as hepatotoxicity in rabbits (Conkova et al., 2001) and piglets (Jiang et al., 2012), haematotoxicity in rats (Maaroufi et al., 1996), oxidative stress in mice (Ben Salah-Abbès et al., 2009) and gilts (Jiang et al., 2011), and cytotoxic effects on cultured Vero cells (Ouanes et al., 2008). Notwithstanding, the effects of ZEA on immune function have been well established in mice (Abbès et al., 2006a, Ben Salah-Abbès et al., 2008) and humans (Vlata et al., 2006), and in vitro (Berek et al., 2001). However, studies of ZEA on immune response of pigs mostly have been conducted with respect to feeding grains naturally contaminated with ZEA and other Fusarium mycotoxins (Swamy et al., 2004). Meanwhile, several changes of immunological parameters were induced by high ZEA concentrations (Abbès et al., 2006a, Ben Salah-Abbès et al., 2008), but such high doses are usually not found in cereals used for animals. Moreover, comprehensive studies regarding ZEA (1.1 to 3.2 mg/kg) effect on splenic damages in post-weanling gilts has not been previously reported.

Therefore, an experiment is conducted to examine whether or not the feeding of a purified ZEA-contaminated (1.1 to 3.2 mg/kg) diet to post-weanling gilts will influence lymphocyte proliferation rate (LPR), interleukin-2 (IL-2) production, mRNA expressions of pro-inflammatory cytokines and histopathologic changes of spleen.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Preparation of zearalenone contaminated diet

Purified ZEA (Fermentek, Jerusalem, Israel) was dissolved in acetic ether, poured onto talcum powder, which was left overnight to allow acetic ether evaporation. A ZEA premix was prepared by blending ZEA-contaminated talcum powder with ZEA-free corn, which was subsequently mixed at appropriate levels with a corn–soybean meal diet to create the experimental diets. All diets were prepared in one batch, stored in covered containers prior to feeding. A composite sample of each experimental diet was prepared for analysis of ZEA and other mycotoxins by the Asia Mycotoxin Analysis Center (Chaoyang University of Technology, Taichung, China) before and at the end of the feeding experiment. Deoxynivalenol (DON) was analyzed using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and fluorometry techniques were used to measure ZEA, fumonisins (FUM), and aflatoxin (AFL) levels. The detection limits of these mycotoxins were 1 μg/kg for AFL, 0.1 mg/kg for ZEA, 0.1 mg/kg for DON, including 3-acetyl deoxynivalenol, 15-acetyl deoxynivalenol, and nivalenol, and 0.25 mg/kg for FUM.

2.2. Experimental design, animals and management

The animals used in all experiments were cared for in accordance with the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals described by the Animal Nutrition Research Institute of Shandong Agricultural University and the Ministry of Agriculture of China. A total of 20 post-weanling piglets (Landrace × Yorkshire × Duroc) with an average body weight of 10.36 ± 1.21 kg (21 d of age) were used in the study. Gilts were randomly allocated into 4 treatments according to body weight after 7 days of adaptation. Pigs were fed a basal diet (Table 1) supplemented with an addition of 0, 1, 2, or 3 mg/kg purified ZEA for 18 days. Analyzed ZEA contents were 0, 1.1 ± 0.02, 2.0 ± 0.01 and 3.2 ± 0.02 mg/kg (means ± SD) in the control and the 3 experimental diets, respectively. Aflatoxin, DON, and FUM were not detected in the test diets.

Table 1.

Ingredients and compositions of the basal diet (air-dry basis).

| Ingredients | Content, % | Nutrients | Analyzed values, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corn | 53.00 | Gross energy, MJ/kg | 17.12 |

| Wheat middling | 5.00 | Crude protein | 19.40 |

| Whey powder | 6.50 | Calcium | 0.84 |

| Soybean oil | 2.50 | Total phosphorus | 0.73 |

| Soybean meal | 24.76 | Lysine | 1.36 |

| Fish meal | 5.50 | Methionine | 0.46 |

| l-lysine HCl | 0.30 | Sulfur amino acid | 0.79 |

| dl-methionine | 0.10 | Threonine | 0.90 |

| l-threonine | 0.04 | Tryptophan | 0.25 |

| Calcium phosphate | 0.80 | ||

| Limestone (pulverized) | 0.30 | ||

| Sodium chloride | 0.20 | ||

| Premix1 | 1.00 |

Supplied per kg of diet: vitamin A, 3,300 IU; vitamin D3, 330 IU; vitamin E, 24 IU; vitamin K3, 0.75 mg; vitamin B1, 1.50 mg; vitamin B2, 5.25 mg; vitamin B6, 2.25 mg; vitamin B12, 0.02625 mg; pantothenic acid, 15.00 mg; niacin, 22.5 mg; biotin, 0.075 mg; folic acid, 0.45 mg; Mn (from MnSO4·H2O), 6.00 mg; Fe (from FeSO4·H2O), 150 mg; Zn (from ZnSO4·H2O), 150 mg; Cu (from CuSO4·5H2O), 9.00 mg; I (from KI), 0.21 mg; Se (from Na2SeO3), 0.45 mg.

The diets used in the study were isocaloric and isonitrogenous with the only difference being in ZEA level. All nutrient concentrations were formulated to meet or exceed minimal requirements according to the NRC (1998). Animals were housed in cages equipped with one nipple drinker and one brick-shaped feeder in a temperature controlled room at Jinzhuyuan Farm (Yinan, Shandong, China). During the experimental period, the temperature in the nursery room was maintained between 26 and 28 °C. The mean relative humidity was approximately 65%. Gilts were fed ad libitum and allowed access to water freely through the entire experiment period.

2.3. Sample collection

Pigs were fasted for 12 h at the end of the experimental period. After the collection of blood samples, piglets were immediately euthanized and spleens were isolated, weighed, and gross lesions examined. Four samples of splenic tissues from each pig were quickly collected, the first portion was put in D-Hank's for LPR and IL-2 measurement, the second was stored at −80 °C for mRNA expressions of cytokines analysis, the third was fixed in 10% buffered formalin for histopathology evaluation, and the fourth was cut into 0.5 mm3 and fixed in 2.5% polyoxymethylene–glutaraldehyde for ultrastructure analysis.

2.4. Splenic lymphocyte proliferation assay

Splenic samples in a proper amount of sterile D-Hank's were gently mashed by pressing with the flat surface of a syringe plunger against a stainless-steel sieve (200 meshes). After the red blood cells were disrupted, the splenocytes were washed twice. The resulting pellet was resuspended and diluted to 2.5 × 106 cells/mL with RPMI-1640 and fetal bovine serum after the cell viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion. The solutions were incubated into 96-well culture plates with 190 μL cell suspension and 10 μL ConA per well. The plates were respectively incubated in a humid atmosphere with 5% CO2 (Thermo) at 37 °C for 72 h. Briefly, 100 μL of methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium (MTT, 5 mg/mL) was added into each well at 4 h before the end of incubation. Then the plates were centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min at room temperature. The supernatant was removed carefully and 100 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added into each well. The plates were shaken for 5 min to dissolve the crystals completely. The absorbance of cells in each well was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reader (Model RT-6100, Leidu Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) at a wave length of 570 nm (A value) as the index of lymphocytes proliferation (Huang et al., 2013). Meanwhile, the lymphocytes proliferation rate was calculated as follows: Proliferation rate (%) = 100 × A(test group)/A(control group).

2.5. Measurement of IL-2 of splenic lymphocytes

Lymphocytes were collected as described above, and then 500 μL cell suspensions were incubated in a humid atmosphere with 5% CO2 (Thermo) at 37 °C for 24 h. The supernatants were collected and the concentrations of IL-2 were assayed by ELISA kit (BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany). Briefly, ELISA plates were precoated with 50 μL of 1:500 diluted capture antibody overnight at 4 °C and afterwards washed and blocked with 100 μL assay diluents (phosphate buffered saline [PBS] with 10% fetal calf serum [FCS]) at room temperature for 1 h. After the washing step, 50 μL standard and culture supernatant (1:4 diluted with PBS) were incubated at room temperature for 1 h, washed and 50 μL detection antibody and streptavidin-HRP reagent were added and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. After subsequent washing steps, 50 μL substrate solutions were added and incubated in the dark for 10 to 30 min. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 50 μL 1 mol/L H2SO4. The measurement was performed using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reader (Model RT-6100, Leidu Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) at a wave length of 450 nm (OD value).

2.6. Histopathological tests

After routine processing, the splenic tissues fixed in 10% formalin were embedded in paraffin. For general orientation, the tissues were sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for microscopy examination. The slides were examined under 100× magnifications using an optical microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany).

2.7. Ultra-structure tests

After routine processing, the splenic tissues fixed in 2.5% polyoxymethylene–glutaraldehyde were postfixed in 1% osmic acid. Tissues were embedded in Epon812 after gradient dehydration in acetone. For general orientation, ultrathin sections were prepared and stained with uranium acetate and lead citrate for examination. The slides were examined under a transmission electron microscope (JEM-2100, JEOL Ltd., Japan).

2.8. mRNA expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines by RT-PCR

The mRNA expression of different cytokines including interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and β-actin were determined using the RT-PCR method. Tissue RNA was extracted using ultra pure RNA extraction kit (Cat#CW0581, CWbio Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). RNA concentrations and integrity were determined by agarose gel electrophoresis using 5 μL RNA. Total RNA was reverse transcribed using HiFi-MMLV cDNA First Strand Synthesis kit (Cat#CW0744, CWbio. Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) with random primers. Real-time RT-PCR reactions were conducted using UltraSYBR Mixture (with Rox, Cat#CW0956, CWbio. Co. Ltd., Beijing, China) by RT-PCR systems (Roche 480). After denaturing at 95 °C for 10 min, PCR amplification was performed for 40 cycles (95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min), followed by a final extension step (72 °C for 10 min). The gene was expressed as relative intensities of β-actin. Oligonucleotides primers for selected gene are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Oligonucleotide primers for selected cytokines.

| Gene | Oligo | Primer sequence (5′to 3′) | Predicted size, bp | Genebank accession No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1β | Forward Primer Reverse Primer |

AAAGGGGACTTGAAGAGAG CTGCTTGAGAGGTGCTGATGT |

285 | NM_001005149 |

| IFN-γ | Forward Primer Reverse Primer |

AAATGGTAGCTCTGGGAAAC TATTGCAGGCAGGATGAC |

207 | NM_213948 |

| IL-6 | Forward Primer Reverse Primer |

GCATTCCCTCCTCTGGTC TCTTCAAGCCGTGTAGCC |

244 | M86722 |

| TNF-α | Forward Primer Reverse Primer |

ACGCTCTTCTGCCTACTGC TCCCTCGGCTTTGACATT |

162 | NM_214022 |

| β-action | Forward Primer Reverse Primer |

GGACTCATGACCACGGTCCAT TCAGATCCACAACCGACACG |

220 | DQ845173 |

IL-1β = interleukin-1β; IFN-γ = interferon-γ; IL-6 = interleukin-6; TNF-α = tumor necrosis factor-α.

2.9. Statistical analysis

All data were subjected to analysis of variance using the GLM procedure of SAS (2003). The data were first analyzed as a completely randomized design with individual piglet as random factor to examine the overall effect of treatments. Orthogonal polynomial contrasts were then used to determine linear responses to ZEA levels of treatments. The significance differences among treatments were tested using Duncan's multiple range tests. All statements of significance were based on the probability of P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Lymphocyte proliferation rate and IL-2 production of spleen

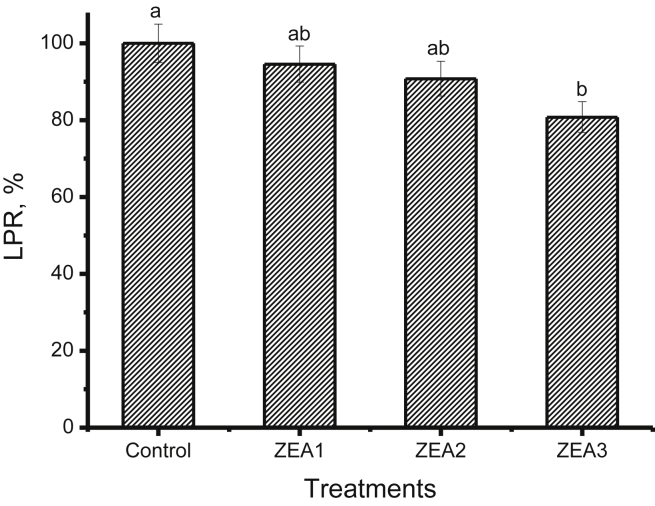

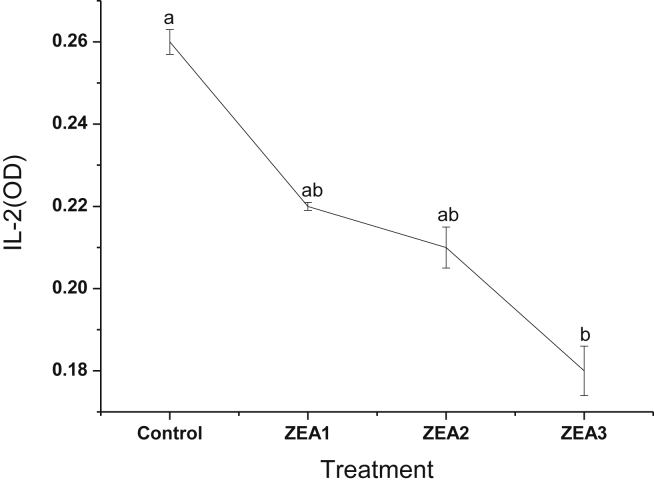

Gilts fed the diet containing 3.2 mg/kg ZEA had reduced (P < 0.05) LPR of spleen compared with the control, and the LPR was reduced linearly as dietary ZEA levels increased (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1). Linear decrease in IL-2 production of spleen was also observed (P < 0.05), and IL-2 production in the gilts fed 3.2 mg/kg ZEA-contaminated diet was significantly lower (P < 0.05) than any other 3 treatments (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Effects of different levels of zearalenone (ZEA) on lymphocyte proliferation rate (LPR) in spleen of gilts. Data are means for 5 replicates per treatment. Zearalenone was not detectable in control diet; ZEA1, ZEA2 or ZEA3 represents the control diet with an addition of 1.1, 2.0 or 3.2 mg/kg ZEA, respectively. Different letters above standard error bars indicate statistically significant differences among treatments (P < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Effects of different levels of zearalenone (ZEA) on interleukin-2 (IL-2) production in spleen of gilts. Data are means for 5 replicates per treatment. Zearalenone was not detectable in control diet; ZEA1, ZEA2 or ZEA3 represents the control diet with an addition of 1.1, 2.0 or 3.2 mg/kg ZEA, respectively. Different letters above standard error bars indicate statistically significant differences among treatments (P < 0.05).

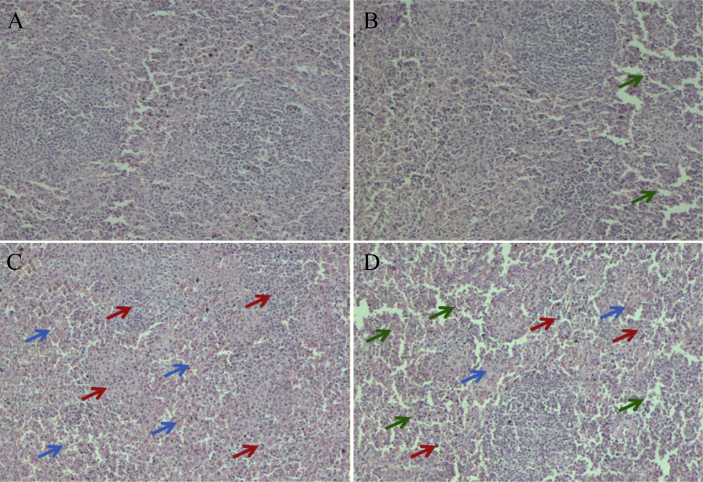

3.2. Histopathological examination

Normal histological pictures were observed in control group (Fig. 3). Swelling splenocyte (green arrows) from 1.1 mg/kg ZEA treatments were observed. Splenic sections from gilts treated with 2.0 and 3.2 mg/kg ZEA showed significant atrophy of white pulp (red arrows) and swelling of red pulp (blue arrows).

Fig. 3.

Photomicrographs of hematoxylin and eosin stained spleen sections of gilts after feeding different levels of zearalenone (ZEA) contaminated feeds (100× original magnification). Zearalenone was not detectable in (A) control diet; (B) ZEA1, (C) ZEA2 or (D) ZEA3 represent the control diet with an addition of 1.1, 2.0 or 3.2 mg/kg ZEA in the experiment treatments. Green, red, and blue arrows represent swelling splenocyte, atrophy of white pulp and swelling of red pulp, respectively.

3.3. Ultra-structure examination

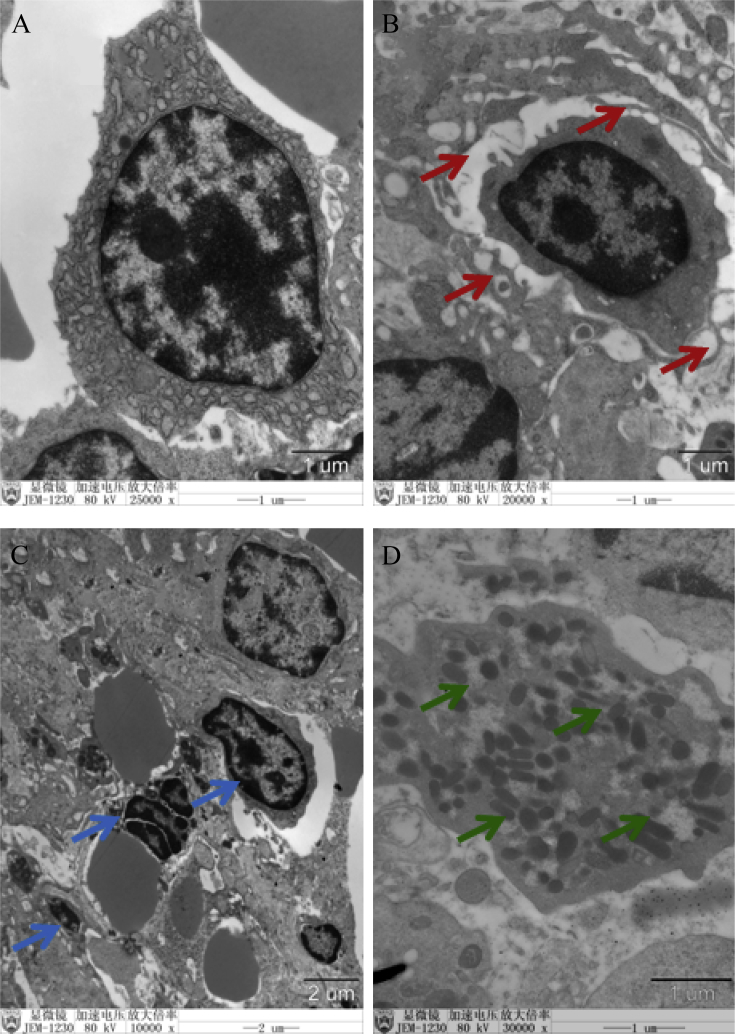

Normal histological pictures were observed in control group (Fig. 4). The obvious cytoplasmic edema (red arrows) in 1.1 mg/kg ZEA treatments was observed. Ultrastructures of spleen from gilts treated with 2.0 mg/kg ZEA showed significant chromatin deformation such as chromatin condensation, crescentiform or half-moon of the condensed chromatin (blue arrows). The increased phagocytosis (green arrows) was observed in splenic sections from gilts treated with 3.2 mg/kg ZEA.

Fig. 4.

Ultrastructural photos of spleen sections of gilts after feeding different levels of zearalenone (ZEA) contaminated feeds. Zearalenone was not detectable in (A) control diet; (B) ZEA1, (C) ZEA2 or (D) ZEA3 represent the control diet with an addition of 1.1, 2.0 or 3.2 mg/kg ZEA in the experiment treatments. Green, red, and blue arrows represent phagocytosis, cytoplasmic edema and chromatin deformation, respectively.

3.4. mRNA expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines

The mRNA expressions of tested cytokines in the spleen of gilts are illustrated in Table 3. All data were expressed as relative intensities of β-actin, a housekeeping gene. The 2.0 or 3.2 mg/kg ZEA challenged groups up-regulated (P < 0.05) the expression levels of IL-1β and IL-6, however, IFN-γ in gilts fed the diet containing 2.0 or 3.2 mg/kg ZEA was down-regulated (P < 0.05) compared with the control. Linear effect on IL-1β, IL-6, and IFN-γ was observed as dietary ZEA levels increased (P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Effect of different levels of zearalenone on the mRNA expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the spleen of gilts.1

| Item | Control2 | ZEA12 | ZEA22 | ZEA32 | SEM | Effects (P-value) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Linear | ||||||

| IL-1β | 0.14b | 0.15b | 0.19a | 0.20a | 0.003 | 0.003 | <0.001 |

| IL-6 | 0.36c | 0.52c | 0.93b | 1.27a | 0.013 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| IFN-γ | 1.19a | 1.01a | 0.80b | 0.62b | 0.033 | 0.001 | 0.002 |

| TNF-α | 0.56 | 0.46 | 0.48 | 0.53 | 0.021 | 0.257 | 0.113 |

IL-1β = interleukin-1β; IFN-γ = interferon-γ; IL-6 = interleukin-6; TNF-α = tumor necrosis factor-α; SEM = standard error of the means.

a, b, cMeans within a row with different letters differ significantly (P < 0.05).

Data are means for 5 replicates per treatment. Data per piglet were run in triplicate in a single assay to avoid inter-assay variation.

Zearalenone was not detectable in control diet; ZEA1, ZEA2 or ZEA3 represents the control diet with an addition of 1.1, 2.0 or 3.2 mg/kg zearalenone in the experiment treatments, respectively.

4. Discussion

The similar growth rate, feed intake, and feed efficiency of the piglets among all the treatments indicated that pigs within a treatment likely consumed a similar amount of ZEA, and that different obtained among treatments were likely attributable to the different concentrations of ZEA in the diet (Jiang et al., 2011).

Success to observe the effect of ZEA-contaminated diets (1.1 to 3.2 mg/kg) on the LPR, IL-2, mRNA expressions of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and histopathologic changes of spleen in the current study may be very significant. The proliferation of lymphocytes was a normal protective and physiological reaction when body immune system was stimulated by foreign antigen, which was significance in resisting infection by foreign organisms. Zearalenone, α-ZOL and β-ZOL could induce cytotoxicity of immune cells, and it was reported that 10−5 mol/L ZEA and its metabolites inhibited the proliferation of neutrophil (Muratori et al., 2003). Even low concentrations of ZEA (10 μmol/L) could inhibit the proliferation of thymoma Jurkat T cells, and the effect was ZEA induced T cell apoptosis (Luongo et al., 2006). Zearalenone not only inhibited proliferation of human peripheral blood lymphocytes stimulated by phytohemagglutin phytolectin, but also inhibited the formation of B cells and T cells stimulated by Concanavalin A and pokeweed mitogen (Vlata et al., 2006). Study confirmed that ZEA suppressed the synthesis of proteins and DNA, blocked cell cycle proceeding at the G2/M stage and DNA replication, and thereby inhibited cell proliferation (Abid-Essefi et al., 2004). It had been verified that if there were heavy loads in the DNA repair system due to excessive damage, cell apoptosis or other types of cell death occurred, which may explain why cell viability decreased (Orren et al., 1997). In the present study, the MTT method was used to uncover the inhibition of ZEA on cell proliferation of splenic lymphocytes, although the mechanism needs to be confirmed further.

In vivo, T cells produced IL-2 mainly, as well as some precursors of T cells and B cells. In vitro, mitogen, some cytokines and drugs were all able to induce the production of IL-2 in lymphocytes. Recently, IL-2, as a molecular vaccine adjuvant, has often been used to enhance immune effects, especially in enhancing cellular immune responses (Long et al., 2013). Studies have shown that α-ZOL (40 and 80 μmol/L) significantly decreased the expression level of IL-2 in Thymoma T cells (Luongo et al., 2006). Contaminated daily diets (DON: 1 mg/kg, ZEA: 0.25 mg/kg) dramatically decreased the expression of cytokine IL-2 of spleen in weanling pigs (Cheng et al., 2006). In the current experiment, the level of IL-2 in the spleen of gilts treated with 3.2 mg/kg ZEA were dramatically lower than those of the control group, and IL-2 decreased linearly with increasing level of ZEA. Due to the fact that IL-2 is a kind of cytokine which is essential for the proliferation and differentiation of T cells, the reasons of decreased levels of IL-2 in spleen induced by 3.2 mg/kg ZEA could be explained by the fact that there was a decreased proliferation rate of splenic lymphocytes.

The spleen is the main immune organs of the animal body, and it was closely related to humoral and cellular immunity. The effect of ZEA on histological structure of spleen was rarely reported. No pathological changes of splenic tissues were observed among the B6C3F1 mouse treated with 10 mg/kg ZEA 8 weeks later (Forsell et al., 1986). Mice treated with ZEA (40 mg/kg BW) induced swelling in the splenocytes, focal necrosis, atrophy of white pulp and red pulp dilatation (Abbès et al., 2006b). The stimulation is that the swelling splenocyte in 1.1 mg/kg ZEA treatments, atrophy of white pulp and swelling of red pulp in 2.0 and 3.2 mg/kg ZEA treatments were also observed in the present study. The effect of ZEA on the ultrastructure of splenic tissue has not been reported so far. In the present study, the increased phagocytosis in gilts treated with 3.2 mg/kg ZEA, significant chromatin deformation in gilts treated with 2.0 mg/kg ZEA, and the obvious cytoplasmic edema in 1.1 mg/kg ZEA treatments suggesting that there was a negative effect of ZEA (1.1 to 3.2 mg/kg) on structural lesion of spleens in post-weanling piglets.

The intrusion of external pathogenic factors (such as bacteria and viruses) triggered the immune cells (such as macrophages and lymphocytes) synthesize and release a series of chemical substances including IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α, and these proinflammatory cytokines play an important role in infectious immunity (Choic et al., 1999, Decker, 1990, Nathan, 1987). The positive correlation between the immunity of classical swine fever vaccine by virulent virus attack and the levels of IFN-γ in vivo suggested that the immune state of antiviral infection can be indicated by the levels of IFN-γ (Suradhat et al., 2001). Research reported that α-ZOL (40 and 80 μmol/L) significantly reduced the expression levels of IL-2 and γ-IFN in thymoma T cells (Luongo et al., 2006). The DON (1 mg/kg) and ZEA (0.25 mg/kg) challenged pigs decreased the expression of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-2 and IL-6 in spleens (Cheng et al., 2006). Up-regulation of IL-1β and IL-6 and down-regulation of IFN-γ in the gilts treated with ZEA (2.0 and 3.2 mg/kg) in the present study demonstrated that ZEA caused local or systemic inflammatory response, notwithstanding, the underlying mechanism still requires further exploration.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the current study demonstrated that ZEA feeding at 1.1 to 3.2 mg/kg for 18 days induced different degrees of toxicity in spleens of post-weanling gilts as indicated by the changes in lymphocyte proliferation rate, IL-2, histopathological and ultra-structure examinations tested in this study. The most parameters were linearly affected as dietary ZEA concentrations increased. Besides its estrogenic effects, the study showed the increase of toxicity in spleens of gilts fed ZEA contaminated feeds provides another possible pathway of ZEA toxicity in pigs. More cellular and molecular studies are needed to understand ZEA biological mode of actions and the toxicity of ZEA thoroughly.

Conflict of interest

We certify that there is no conflict of interests with any financial, professional or personal that might have influenced the performance or presentation of the work described in this manuscript.

Acknowledgment

This research was financed by National Nature Science Foundation of China (Project No. 31572441) and special funds of modern agricultural industry technology system of pig industry of the Shandong Province (SDAIT-08-04). The authors wish to thank Dr. Chia Chung Chen at Chaoyang University of Technology, Taiwan, China, for his assistance on mycotoxins analysis and general chemistry consultations.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

Contributor Information

Shuzhen Jiang, Email: shuzhen305@163.com.

Zaibin Yang, Email: yzb204@163.com.

References

- Abbès S., Salah-Abbès J.B., Ouanes Z., Houas Z., Othman O., Bacha H. Preventive role of phyllosilicate clay on the immunological and biochemical toxicity of zearalenone in Balb/c mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:1251–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbès S., Ouanes Z., Salah-Abbès J.B., Houas Z., Oueslati R., Bacha H. The protective effect of hydrated sodium calcium aluminosilicate against haematological, biochemical and pathological changes induced by zearalenone in mice. Toxicon. 2006;47:567–574. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abid-Essefi S., Ouanes Z., Hassen W. Cytotoxicity, inhibition of DNA and protein syntheses and oxidative damage in cultured cells exposed to zearalenone. Toxicol In Vitro. 2004;18:467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2003.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Salah-Abbès J., Abbès S., Houas Z., Abdel-Wahhab M.A., Oueslati R. Zearalenone induces immunotoxicity in mice: possible protective effects of Radish extract (Raphanus Sativus) J Pharm Pharmacol. 2008;60:1–10. doi: 10.1211/jpp.60.6.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Salah-Abbès J., Abbès S., Abdel-Wahhab M.A., Oueslati R. Raphanus sativus extract protects against zearalenone induced reproductive toxicity, oxidative stress and mutagenic alterations in male Balb/c mice. Toxicon. 2009;53:525–533. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berek L., Petri I.B., Mesterhazy A., Teren J., Molanr J. Effects of mycotoxins on human immune functions in vitro. Toxicol In Vitro. 2001;15:25–30. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2333(00)00055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y.H., Weng C.F., Chen B.J., Chang M.H. Toxicity of different Fusarium mycotoxins on growth performance, immune responses and efficacy of a mycotoxin degrading enzyme in pigs. Anim Res. 2006;55:579–590. [Google Scholar]

- Choic C., Kwon D., Min K., Chae C. In-situ hybridization for the detection of inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, TNF-α and IL-6) in pigs naturally infected with Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. J Comp Pathol. 1999;121:349–356. doi: 10.1053/jcpa.1999.0332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conkova E., Laciakova A., Pastorova B., Seidel H., Kovac G. The effect of zearalenone on some enzymatic parameters in rabbits. Toxicol Lett. 2001;121:145–149. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(01)00312-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker K. Biologically active products of stimulated liver macrophages (Kupffer cells) Eur J Biochem. 1990;192:245–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EC Commission recommendation of 17 August 2006: on the presence of deoxynivalenol, zearalenone, ochratoxin A, T-2 and HT-2 and fumonisins in products intended for animal feeding. Off J Eur Union. 2006;576(L229):7–9. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA Opinion of the Scientific Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain on a request from the commission related to zearalenone as undesirable substance in animal feed. EFSA J. 2004;89:1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Etienne M., Jemmali M. Effects of zearalenone (F2) on estrous activity and reproduction in gilts. J Anim Sci. 1982;55:1–10. doi: 10.2527/jas1982.5511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsell J.H., Witt M.F., Tai J.H., Jensen R., Pestka J.J. Effects of 8-week exposure of the B6C3F1 mouse to dietary deoxynivalenol (vomitoxin) and zearalenone. Food Chem Toxicol. 1986;24:213–219. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(86)90231-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Jiangn C., Hu Y., Zhao X., Shi C., Yu Y. Immunoenhancement effect of rehmannia glutinosa polysaccharide on lymphocyte proliferation and dendritic cell. Carbohydr Polym. 2013;96:516–521. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S.Z., Yang Z.B., Yang W.R., Yao B.Q., Zhao H., Liu F.X. Effects of feeding purified zearalenone contaminated diets with or without clay enterosorbent on growth, nutrient availability, and genital organs in post-weaning female pigs. Asian Austral J Anim Sci. 2010;23:74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S.Z., Yang Z.B., Yang W.R., Gao J., Liu F.X., Broomhead J. Effects of purified zearalenone on growth performance, organ size, serum metabolites, and oxidative stress in postweaning gilts. J Anim Sci. 2011;89:3008–3015. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-3658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S.Z., Yang Z.B., Yang W.R., Wang S.J., Wang Y., Broomhead J. Effect on hepatonephric organs, serum metabolites and oxidative stress in post-weaning piglets fed purified zearalenone contaminated diets with or without Calibrin-Z. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 2012;96:1147–1156. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0396.2011.01233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long S.A., Buckner J.H., Greenbaum C.J. IL-2 therapy in type 1 diabetes: “Trials” and tribulations. Clin Immunol. 2013;149:324–331. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luongo D., Severino L., Bergamo P., De-Luna R., Lucisano A., Rossi M. Interactive effects of fumonisin B1 and α-zearalenol on proliferation and cytokine expression in Jurkat T cells. Toxicol In Vitro. 2006;20:1403–1410. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maaroufi K., Chekir L., Creppy E.E., Ellouz F., Bacha H. Zearalenone induces, modifications of haematological and biochemical parameters in rats. Toxicon. 1996;34:535–540. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(96)00008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muratori M., Maggi M., Spinelli S., Filimberti E., Forti G., Baldi E. Spontaneous DNA fragmentation in swim-up selected human spermatozoa during long term incubation. J Androl. 2003;24:253–262. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2003.tb02670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan C.F. Secretory products of macrophages. J Clin Investig. 1987;79:319–326. doi: 10.1172/JCI112815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NRC . 10th ed. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1998. Nutrient requirements of swine. [Google Scholar]

- Orren D.K., Petersen L.N., Bohr V.A. Persistent DNA damage inhibits S-phase and G2 progression, and results in apoptosis. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1129–1142. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.6.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouanes Z., Golli E.E., Abid S., Bacha H. Cytotoxicity effects induced by Zearalenone metabolites, α-Zearalenol and β-Zearalenol, on cultured Vero cells. Toxicology. 2008;252:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.07.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute . 1st ed. SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, North Carolina, USA: 2003. SAS/STAT user's guide: version 9. [Google Scholar]

- Suradhat S., Intrakamhaeng M., Damrongwatenapokin S. The correlation of virus-specific interferon-γ production and protection against classical Swine fever virus infection. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2001;83:177–189. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(01)00389-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swamy H.V., Smith T.K., Karrow N.A., Boermans H.J. Effects of feeding blends of grains naturally contaminated with Fusarium mycotoxins on growth and immunological parameters of broiler chickens. Poult Sci. 2004;83:533–543. doi: 10.1093/ps/83.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlata Z., Porichis F., Tzanakakis G., Tsatsakis A., Krambovitis E. A study of zearalenone cytotoxicity on human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Toxicol Lett. 2006;165:274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warth B., Parich A., Atehnkeng J., Bandyopadhyay R., Schuhmacher R., Sulyok M. Quantitation of mycotoxins in food and feed from Burkina Faso and Mozambique using a modern LC-MS/MS multitoxin method. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:9352–9363. doi: 10.1021/jf302003n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W., Ma J.J., Yu C.C., Lin X.H., Jiang H.R., Shao B. Simultaneous determination of masked deoxynivalenol and some important type B trichothecenes in Chinese corn kernels and corn-based products by ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:11638–11646. doi: 10.1021/jf3038133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinedine A., Soriano J.M., Moltó J.C., Mañes J.M. Review on the toxicity, occurrence, metabolism, detoxification, regulations and intake of zearalenone: an oestrogenic mycotoxin. Food Chem Toxicol. 2007;45:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]