Abstract

This work has been undertaken to study the occurrence of Clostridium perfringens contamination in the poultry feed ingredients and find out its in-vitro antibiotic sensitivity pattern to various antimicrobial drugs. Two hundred and ninety-eight poultry feed ingredient samples received at Poultry Disease Diagnosis and Surveillance Laboratory, Namakkal, Tamil Nadu in South India were screened for the presence of C. perfringens. The organisms were isolated in Perfringens agar under anaerobic condition and subjected to standard biochemical tests for confirmation. In vitro antibiogram assay has been carried out to determine the sensitivity pattern of the isolates to various antimicrobial drugs. One hundred and one isolates of C. perfringens were obtained from a total of 298 poultry feed ingredient samples. Overall positivity of 33.89% could be made from the poultry feed ingredients. Highest level of C. perfringens contamination was detected in fish meal followed by bone meal, meat and bone meal and dry fish. Antibiogram assay indicated that the organisms are highly sensitive to gentamicin (100%), chlortetracycline (96.67%), gatifloxacin (93.33%), ciprofloxacin (86.67%), ofloxacin (86.67%) and lincomycin (86.67%). All the isolates were resistant to penicillin-G. Feed ingredients rich in animal proteins are the major source of C. perfringens contamination.

Keywords: Poultry feed ingredients, Contamination, Clostridium perfringens, Isolation, Identification, Antibiogram

1. Introduction

Poultry industry is one of the fastest growing sectors in India. As per the report from the Ministry of Agriculture, Govt. of India, the average growth rate in egg production and broiler production is 8% and 14% per annum, respectively. Various sources of environmental pollutants and microbes are contaminating poultry produce and animal feed (D'Mello, 2004). There are different modes of pathogen transmission in poultry diseases. Transmission of pathogens via the contamination of feed and feed ingredients causes infections in birds thereby leading to low production performance and economic losses. There are many microbes, including Clostridium perfringens, spread through contaminated feed (Tessari et al., 2014).

C. perfringens is a Gram positive, anaerobic, spore-forming, rod shaped bacterium. It is ubiquitous in nature and can be found as a normal component of soil, contaminated food, decaying vegetation, marine sediment, intestinal tract of birds and poultry litter. The C. perfringens type A causes necrotic enteritis (NE) in poultry (Longo et al., 2010, Opengart and Songer, 2013, Moore, 2015), the acute form of the disease causes high mortality in broiler birds (Kaldhusdal and Lovland, 2000), where as the subclinical form causes erosion of intestinal mucosa results in decreased digestion and absorption, depressed weight gain and increased FCR (Kaldhusdal et al., 2001, Hofacre et al., 2003).

Among foodborne diseases in humans, C. perfringens is one of the most frequently isolated bacterial pathogens apart from Campylobacter and Salmonella (Buzby and Roberts, 1997).

Poultry feed ingredients contaminated by microorganisms may be considered in relation to the performance of birds and also with the public health significance. With this background, the present study was undertaken to study the occurrence of C. perfringens contamination in poultry feed ingredients.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Samples

From July 2015 to June 2016, a total of 298 poultry feed ingredient samples from different sources received at Poultry Disease Diagnosis and Surveillance Laboratory, Namakkal were screened for the presence of C. perfringens.

2.2. Isolation and identification of C. perfringens

A sample of 50 g feed ingredient was added in 450 mL of distilled water and mixed in a vortex mixer (TARSON) for 15 min. Between each sample preparation, the vortex mixer was cleaned by mopping cloth moistened with 70% isopropyl alcohol. A 50-mL aliquot from the mixture was transferred to a beaker and placed in water bath at 80 °C for 10 min. The mixture was allowed to cool, then 1 mL was inoculated in 10 mL of freshly prepared Robertson's cooked meat medium in Brain Heart Infusion Broth (Himedia, Mumbai) and incubated under anaerobic condition at 37 °C for 24 to 48 h. A loopful of inoculum from the broth was streaked into Perfringens agar plates with supplements (Perfringens supplement I Sodium sulphadiazine), Perfringens supplement II (Oleandomycin phosphate and Polymyxin B sulphate) (Himedia, Mumbai) and incubated under anaerobic condition at 38 to 40 °C for 24 h. The plates were observed for the growth of characteristic colonies of C. perfringens. The suspected colonies were subjected to Gram's staining and biochemical tests for identification and confirmation.

2.3. Stormy fermentation test

Stormy fermentation test as described by Tessari et al. (2014) was performed with slight modifications to identify gas and acid production by C. perfringens. The suspected colony from Perfringens agar was inoculated in 5 mL of litmus milk medium. One millilitre of liquid paraffin was added over the medium to form a layer to produce anaerobiosis. Then the tubes were incubated under anaerobic condition at 37 °C for 14 to 24 h.

2.4. Lecithinase test

The suspected colony from Perfringens agar was streaked on 10% egg yolk agar plate. Then the plates were incubated under anaerobic condition at 37 °C for 24 h.

2.5. Antibiogram assay

Disc diffusion method as described by Bauer et al. (1966) was performed to determine the sensitivity pattern of C. perfringens isolates to various antibiotics. A total of 30 isolates of C. perfringens were subjected to in-vitro antibiogram assay. The antibiotic discs (Himedia, Mumbai) used in this study were gatifloxacin (30 mcg), ciprofloxacin (5 mcg), gentamicin (30 mcg), co-trimoxazole (1.25/23.75 mcg), penicillin G (2 IU), neomycin (10 mcg), ofloxacin (5 mcg), chlortetracycline (30 mcg), lincomycin (15 mcg) and bacitracin (10 units).

3. Results

A total number of 101 C. perfringens isolates were obtained from the 298 feed samples screened. The isolates were confirmed as they produced saccharolytic reaction in Robertson's cooked meat medium in Brain Heart Infusion Broth and typical black line over the roughed edged white colonies on Perfringens agar. Smears made from individual colonies revealed Gram positive, spore forming and large sized rods by Gram staining. The isolates produced typical stormy fermentation reaction in litmus milk medium and they also produced a zone of opalescence around the colonies in egg yolk agar (Fig. 1). Thus, the isolates were identified as C. perfringens on the basis of their cultural, morphological and biochemical characteristics.

Fig. 1.

Lecithinase activity of Clostridium perfringens in egg yolk agar.

Among the 101 C. perfringens isolates obtained from the feed samples the overall positivity was 33.89% (Table 1). The highest level of C. perfringens contamination was observed in fish meal (55.26%) followed by bone meal (44.83%), meat and bone meal (42.86%) and dry fish (38.46%).

Table 1.

Isolation of Clostridium perfringens from various poultry feed ingredients.

| No. | Sample details |

C. perfringens contamination |

Total number of samples | Positivity percentage, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||||

| 1 | Meat and bone meal | 39 | 52 | 91 | 42.86 |

| 2 | Bone meal | 13 | 16 | 29 | 44.83 |

| 3 | Soya meal | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| 4 | Rape seed meal | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 5 | Fish meal | 21 | 17 | 38 | 55.26 |

| 6 | Layer Feed | 21 | 72 | 93 | 22.58 |

| 7 | Chicken meal | 2 | 20 | 22 | 9.09 |

| 8 | Dry fish | 5 | 8 | 13 | 38.46 |

| 9. | De oiled rice bran | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| 10 | Dried milk powder | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 11 | Probiotic supplement | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| 12 | Maize | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Total | 101 | 197 | 298 | 33.89 | |

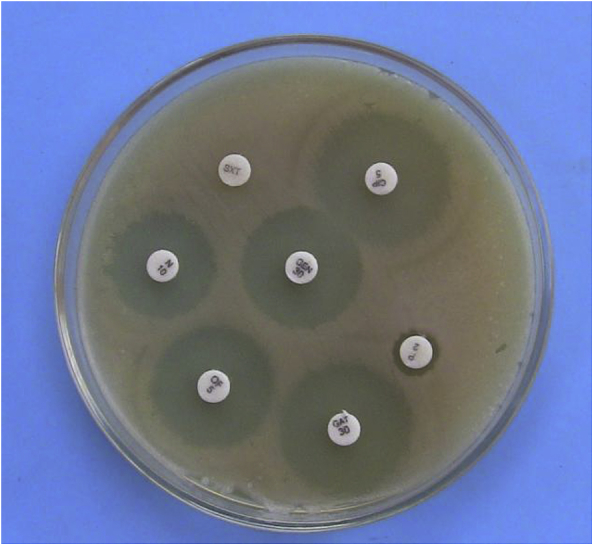

The antibiotic sensitivity pattern (Fig. 2) of 30 isolates of C. perfringens shown in Table 2. The isolates were highly sensitive to gentamicin (100%), chlortetracycline (96.67%), gatifloxacin (93.33%), ciprofloxacin (86.67%), ofloxacin (86.67%) and lincomycin (86.67%). A low degree of susceptibility was observed to neomycin (20%), co-trimoxazole (6.67%) and bacitracin (6.67%). All the isolates were highly resistant to penicillin-G.

Fig. 2.

Antibiotic sensitivity pattern of Clostridium perfringens in Mueller Hinton agar.

Table 2.

In-vitro antibiotic sensitivity pattern of Clostridium perfringens to various antibiotics.

| Name of the antibiotic | Disc content, mcg | Number of isolates showing sensitivity | Sensitivity, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gatifloxacin | 30 | 28 | 93.33 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 5 | 26 | 86.67 |

| Gentamicin | 30 | 30 | 100 |

| Co-trimoxazole | 1.25/23.75 | 2 | 6.67 |

| Penicillin G | 2 IU | 0 | 0 |

| Neomycin | 10 | 6 | 20 |

| Ofloxacin | 5 | 26 | 86.67 |

| Chlortetracycline | 30 | 29 | 96.67 |

| Lincomycin | 15 | 26 | 86.67 |

| Bacitracin | 10 units | 2 | 6.67 |

4. Discussion

The presence of C. perfringens in feed is directly correlated with the level of faecal and soil contamination (Wojdat et al., 2006). High protein contents in poultry feed seems to increase the incidence of C. perfringens infection. Animal protein ingredients such as fishmeal or meat and bone meal in poultry feed increased the risk of necrotic enteritis in poultry (Kocher, 2003, Wu et al., 2014).

Out of 298 poultry feed ingredients analysed, C. perfringens was detected in 33.89% of samples. The highest level of contamination with C. perfringens was observed in fish meal (55.26%) followed by bone meal (44.83%), meat and bone meal (42.86%) and dry fish (38.46%) and all of these are high protein meals of animal origin. The lowest level of C. perfringens contamination was noticed in vegetable protein sources soya meal, maize and rape seed meal. But due to the very low number of samples tested, it is difficult to draw a solid conclusion to say that vegetable protein sources in general have low C. perfringens contamination.

Similar to the present study, several studies have been carried out to determine C. perfringens contamination in poultry feed ingredients. Richardson (2008) found similar levels of C. perfringens contamination in different poultry feed ingredients. Wojdat et al. (2006) detected C. perfringens in 38% of the ingredients used in broiler feed production, with the highest level of contamination in fish meal and meat meal. Schocken-Iturrino et al. (2010) observed 42% of broiler feed samples were contaminated by C. perfringens.

The current study found that fish meal, bone meal and meat and bone meal were the important sources of C. perfringens contamination. Since C. Perfringens is a normal micro flora of soil, contamination of raw feed materials with soil, dust or from workers during drying is practically unavoidable (Mcclane, 2004).

The antibiotic sensitivity pattern in this study revealed the C. perfringens isolates were 100% sensitive to Gentamicin followed by 96.67% to Chlortetracycline, 93.33% to gatifloxacin, 86.67% to ciprofloxacin, 86.67% to ofloxacin and 86.67% to lincomycin. A low level of susceptibility was observed to neomycin (20%), cotrimazine (6.67%) and bacitracin (6.67%). All the isolates were resistant to penicillin-G. Agarwal et al., 2009, Mehtaz et al., 2013 and Ibrahim et al. (2001) found that similar antibiotic sensitive patterns where the C. perfringens isolates were found to be sensitive to fluoroquinolones such as ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin.

Algammal and Elfeil (2015) found 100% resistance of C. perfringens to Neomycin which is a commonly used antimicrobial drug to treat bacterial enteritis in poultry. But in our study 20% of isolates showed sensitivity to Neomycin. Sulfonamide-Trimethoprim is another drug commonly used for the treatment of respiratory diseases in poultry. In this study only 6.67% of the isolates were sensitive to Co-Trimoxazole and agrees with the findings of Llanco et al. (2012) and Eldin et al. (2015).

In our study, none of the isolates was shown sensitivity to Penicillin-G. Where as, Algammal and Elfeil (2015) and Gad et al. (2011) recorded a high level of sensitivity of C. perfringens to Penicillin. The difference in the pattern of sensitivity as resistant to Penicillin-G might be due to indiscriminate use of the drug in poultry industry.

5. Conclusion

C. perfringens contamination was found to be high in animal protein sources used in poultry feed under tropical climatic conditions. The highest level of C. perfringens contamination was detected in fish meal followed by bone meal, meat and bone meal and dry fish purchased from different sources. The C. perfringens isolates showed varying degree of sensitivity to commonly used antibiotics like Gentamicin, Chlortetracycline, Lincomycin and Fluoroquinolones and resistance to Penicillin-G. This study also further warns that extensive surveillance of C. perfringens in poultry feed ingredients and formulate suitable alternative strategies to control this organism in poultry feed.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Director, Centre for Animal Health Studies, Tamil Nadu Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Chennai, India.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

References

- Agarwal A., Narang G., Rakha N.K., Mahajan N.K., Sharma A. In vitro lecithinase activity and antibiogram of clostridium perfringens isolated from broiler chickens. Haryana Vet. 2009;48:81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Algammal A.M., Elfeil W.M. PCR based detection of Alpha toxin gene in Clostridium perfringens strains isolated from diseased broiler chickens. Ben Vet Med J. 2015;29(2):333–338. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer M.R., Kirby W.M.M., Sherris J.C., Truck M. Antibiotics susceptibility testing by a standard single disc method. Am J Clin Pathol. 1966;45:493–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzby J.C., Roberts T. Economic costs and trade impacts of microbial foodborne illness. World Health Stat Quart. 1997;50:57–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldin A.H.S., Fawzy E.H., Aboelmagd B.A., Ragab E.A., Shaimaa B. Clinical and laboratory studies on chicken isolates of Clostridium Perfringens in El-Behera, Egypt. J World's Poult Res. 2015;5(2):21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gad W., Hauck R., Kruger M., Hafez H.M. Determination of antibiotic sensitivities of Clostridium perfringens isolates from commercial turkeys in Germany in vitro. Arch Geflugelk. 2011;75(2):80–83. [Google Scholar]

- Hofacre C.L., Beacorn T., Collett S., Mathis G. Using competitive exclusion, mannan-oligosaccharide and other intestinal products to control necrotic enteritis. J Appl Poult Res. 2003;12:60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim R.S., Ibtihal M.M., Soluman A.M. Clostridial infection in chickens studying the pathogenicity and evaluation of the effect of some growth promoter on broiler performance. Assiut Vet Med J. 2001;45:253–267. [Google Scholar]

- Kaldhusdal M., Lovland A. The economical impact of Clostridium perfringens is greater than anticipated. World Poultry. 2000;16:50–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kaldhusdal M., Schneitz C., Hofshagen M., Skjerve E. Reduced incidence of Clostridium perfringens -associated lesions and improved performance in broiler chickens treated with normal intestinal bacteria from adult fowl. Avi Dis. 2001;45:149–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocher A. Nutritional manipulation of necrotic enteritis outbreak in broilers. Rec Adv Anim Nutr Aust. 2003;14:111–116. [Google Scholar]

- Llanco L.A., Viviane N., Ferreira A.J., Avilacampos M.J. Toxinotyping and antimicrobial susceptibility of Clostridium Perfringens isolated from broiler chickens with necrotic enteritis. Int J Microbiol Res. 2012;4:290–294. [Google Scholar]

- Longo F.A., Silva I.F., Lanzarin M.A. XI poultry symposium of South Brazil and Poultry Fair II South Brazil, Chapeco. 2010. The importance of microbiological control in poultry rations. [Google Scholar]

- Mcclane B.A. Clostridial enterotoxin. In: Durre P., editor. Handbook on Clostridia. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 2004. pp. 385–406. [Google Scholar]

- Mehtaz S., Borah P., Sharma R.K., Chakraborty A. Antibiogram of Clostridium Perfringens isolated from animals and foods. Indian Vet J. 2013;90(1):54–56. [Google Scholar]

- D'Mello J.P.F. FAO animal production and health paper, FAO for United Nations, Rome. 2004. Contaminants and toxins in animal feeds; pp. 107–127. [Google Scholar]

- Moore R.J. Necrotic enteritis in chickens: an important disease caused by Clostridium perfringens. Microbiol Aust. 2015;36(3):118–119. [Google Scholar]

- Opengart K., Songer J.S. Necrotic enteritis. In: Swayne D.E., Glisson J.R., McDougald L.R., Nolan Lisa K., Suarez D.L., Venugopal Nair, editors. Diseases of poultry. 13th ed. 2013. pp. 949–953. Ames, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson K.E. Proceedings of 20th Central American Poultry Congress, Managua, Nicaragua. 2008. Reemergence of Clostridia perfringes: is it feed related? [Google Scholar]

- Schocken-Iturrino R.P., Vittori J., Beraldo-Massoli M.C., Delphino T.P.C., Damasceno P.R. Clostridium Perfringens em Rações e Águas Fornecidas a Frangos de corte em Granjas Avícolas do Interior Paulista. Rev Ciênc Rural. 2010;40:197–199. [Google Scholar]

- Tessari E.N.C., Cardoso A.L.S.P., Kanashiro A.M.I., Stoppa G.F.Z., Luciano R.L., Castro A.G.M. Analysis of the presence of Clostridium perfringens in feed and raw material used in poultry production. Food Nutr Sci. 2014;5:614–617. [Google Scholar]

- Wojdat E., Kwiatek K., Kozak M. Occurrence and characterization of some Clostridium species isolated from animal feeding stuffs bull. Bull Vet Inst Pulawy. 2006;50:63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wu S.B., Stanley D., Rodgers N., Swick R.A., Moore R.J. Two necrotic enteritis predisposing factors, dietary fishmeal and Eimeria infection, induce large changes in the caecal microbiota of broiler chickens. Vet Microbiol. 2014;169:188–197. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]