Abstract

Sound feed formulation is dependent upon precise evaluation of energy and nutrients values in feed ingredients. Hence the methodology to determine the digestibility of energy and nutrients in feedstuffs should be chosen carefully before conducting experiments. The direct and difference procedures are widely used to determine the digestibility of energy and nutrients in feedstuffs. The direct procedure is normally considered when the test feedstuff can be formulated as the sole source of the component of interest in the test diet. However, in some cases where test ingredients can only be formulated to replace a portion of the basal diet to provide the component of interest, the difference procedure can be applied to get equally robust values. Based on components of interest, ileal digesta or feces can be collected, and different sample collection processes can be used. For example, for amino acids (AA), to avoid the interference of fermentation in the hind gut, ileal digesta samples are collected to determine the ileal digestibility and simple T-cannula and index method are commonly used techniques for AA digestibility analysis. For energy, phosphorus, and calcium, normally fecal samples will be collected to determine the total tract digestibility, and therefore the total collection method is recommended to obtain more accurate estimates. Concerns with the use of apparent digestibility values include different estimated values from different inclusion level and non-additivity in mixtures of feed ingredients. These concerns can be overcome by using standardized digestibility, or true digestibility, by correcting endogenous losses of components from apparent digestibility values. In this review, methodologies used to determine energy and nutrients digestibility in pigs are discussed. It is suggested that the methodology should be carefully selected based on the component of interest, feed ingredients, and available experimental facilities.

Keywords: Digestibility, Energy, Nutrients, Pigs, Techniques

1. Introduction

Supplying dietary energy and nutrient sufficiently and accurately to pigs would meet the requirement for optimum growth, minimize the cost of the feed ingredients, and reduce the environmental impact from pork production. Because pigs cannot use all the energy and nutrient contents from feed ingredients, an accurate information on bioavailable energy and nutrients is needed (Kong and Adeola, 2014).

Digestibility is currently the most widely used in the evaluation of feedstuffs and diet formulation practices for different stages of pigs (Sauer and Ozimek, 1986). Methods to estimate digestibility of energy and nutrients in feed ingredients have been optimized in recent decades. Efforts have been made to improve these methods and make them more applicable in practice and more accurate in assessments. Traditionally, in vivo digestibility studies have been the most common method to estimate digestibility. In this review, in vivo methodology to evaluate digestibility of energy, amino acids (AA), phosphorus (P), and calcium (Ca) are discussed.

2. Direct and difference procedures

Direct or difference procedures can be applied in in vivo digestibility studies (Adeola, 2001, Agudelo et al., 2010, Jang et al., 2014). In the direct procedure, the test feed ingredient is formulated as the sole source of the component in the test diet (Adeola, 2001). This procedure is relatively easy and simple, only one diet is needed and the determined dietary digestibility of the component is that of the test ingredient. However, direct procedure cannot be applied for all of the feed ingredients, in which the test ingredients cannot be formulated to supply the component of interest alone in the diet. In these situations, difference procedures, including substitution and regression procedures will be applied in which the test ingredient needs to be formulated with other feedstuffs that also supply the component of interest in the test diet. In the substitution procedure, a basal diet is fed to a group of pigs to determine the digestibility of the components. Another group of pigs is fed a test diet with a known proportion of the component from basal diet replacing the test ingredient. The test diet can also be formulated as a basal diet plus a certain quantity of the test ingredient (Adeola and Kong, 2014, Kong and Adeola, 2014). The digestibility of the component in the test ingredients is calculated as described by Kong and Adeola (2014):

| (1) |

where Dbd, Dtd, and Dti are the digestibility (%) of the component in the basal diet, test diet, and test ingredient, respectively, and Pti is the proportion of the component contributed by the test ingredient to the test diet.

Another difference procedure is the regression procedure with multiple points, which is more robust than single point substitution (Fan and Sauer, 2002, Bolarinwa and Adeola, 2012). The digestibility of the component can be used against proportions of the component replaced, and extrapolated to 100% replacement to determine the digestibility of a component in experimental diets (Adeola, 2001).

3. Total collection and index methods

Either total collection method (TM) or index method (IM) can be used to determine the digestibility of the component of interest in the experimental diets. Any of the direct or difference procedures may involve the use of TM or IM. The 4 combinations between the 2 procedures and the 2 methods are widely used in pig digestibility studies. For example, in the study of Adeola et al. (1986), direct method was applied to determine the AA digestibility of corn and triticale using either TM or IM. In the study of Bolarinwa and Adeola (2016), both direct and difference procedures were applied to determine the energy digestibility of barley, sorghum, and wheat using TM. Also in the study of Fan and Sauer (1995), IM was used to determine the AA digestibility through either direct or different procedure. The TM requires a careful collection and record of feed intake and fecal output to determine the difference between the components in consumed feed and excreted feces. The IM allows partial sampling but requires a precise chemical analysis of the indigestible markers (Kong and Adeola, 2014).

3.1. Total collection method (TM)

In a TM study, pigs will be individually housed in metabolism crates and allowed 5 to 7 days adaption to crates and feed. The feeding level is suggested at 3.5 times the maintenance energy requirement or approximately 4% of BW. Previous data showed that the low feed intake could significantly influence AA digestibility (Moter and Stein, 2004). Meanwhile, the feeding level can be slightly reduced to avoid the feed refusal which leads to additional work in refused feed collection and weighing, as well as the potential further chemical analysis of the refused feed (Agudelo et al., 2010, Jang et al., 2014).

The adaptation period is followed by 4 to 6 days of total fecal collection. Fecal collection can be performed using the marker-to-marker method by introducing a colored and indigestible compound at the beginning and the end of the collection period. The assumption for the marker-to-marker collection method is that the ingested marker moves with digesta in the gastrointestinal tract, and it does not diffuse to adjacent unmarked digesta (Adeola, 2001). The fecal collection starts and ends at the observation of marker-colored feces. The fecal output collected during the first and second marker colored feces is assumed to be from the feed consumed between the introducing of the 2 markers in the collection period. The commonly used markers are ferric oxide, chromic oxide (Cr2O3), and indigo carmine (Kong and Adeola, 2014). It is suggested that 1 g of ferric oxide added to 100 g of feed is enough for pigs up to 50 kg body weight (BW), and 2 g of ferric oxide added to 100 g of feed will be sufficient for pigs heavier than 50 kg BW (Adeola, 2001).

A few studies also collected feces by using a “time-based” approach based on the assumption that over an extended adaption period, pigs could achieve a constant feed intake and fecal output during the collection period (Lammers et al., 2008, Anderson et al., 2012, Liu et al., 2012). However, depending on the weight of pig, dietary characteristics, and the housing environment, the average transit time of digesta in growing pigs fluctuates between 24 and 48 h (Potkins et al., 1991), therefore, the feces collected by time-based approach may not totally belong to the recorded feed intake, which would overestimate or underestimate the digestibility values depending on the digesta transit time in gastrointestinal tract (Liu et al., 2012). Limited information is available about the comparison between the marker-to-marker method and time-based approach. Lammers et al. (2008) determined apparent energy digestibility and metabolizability of crude glycerol for growing pigs in 5 experiments. The marker-to-marker approach was used in the first 2 experiments, and the time-based approach was used in Exp. 3, 4, and 5 due to the observation of refusal of feed containing ferric oxide in the first 2 experiments. In all the experiments, the determined energy digestibility and metabolizability of crude glycerol were not affected by the different collection methods across the experiments. However, because of the limited information about the reliability of time-based approach, the marker-to-marker method is suggested for fecal total collection in pigs.

3.2. Index method (IM)

The IM, which requires including a certain concentration of indigestible compound in the diet, has been used as a reliable alternative method to TM, especially when the total collection cannot be undertaken (Moughan et al., 1991, Jagger et al., 1992, Kavanagh et al., 2001, Wang et al., 2016). A proper indigestible compound should have the following properties: 1) totally indigestible and nonabsorbable, 2) nontoxic to the digestive tract, 3) pass through the digestive tract at a relatively uniform rate with digesta, and 4) easy to be analyzed (Moughan et al., 1991). The commonly used indigestible compounds include Cr2O3, titanium dioxide (TiO2), and acid-insoluble ash (AIA), which are normally added at a level from 0.1% to 0.5% (Fenton and Fenton, 1979, Moughan et al., 1991, Jagger et al., 1992, Olukosi et al., 2012). With the analyzed values for nutrients or energy concentration, as well as the concentration of the indigestible compound in feed and the collected feces, the digestibility of component is calculated as follows (Adeola, 2001):

| (2) |

where Mfeed and Mfeces represent concentrations of index compound in feed and feces, respectively; Cfeed and Cfeces represent concentrations of components in feed and feces, respectively.

For improved accuracy of IM-determined digestibility and more meaningful comparison among studies, the sampling and collection procedures should be standardized. In the study of Agudelo et al. (2010), the results showed that after introducing the corn-soybean meal based diet that included Cr2O3, the fecal Cr2O3 concentration linearly increased from d 1 to 5 before reaching a plateau on day 5. Jang et al. (2014), also suggested that at least 5-days adaptation period is required before the digesta marker percentage stabilizes after feeding a corn-soybean meal based diet containing Cr2O3. Moreover, because there may be a discrepancy in the intestinal passage rate between marker and low digestible compounds (Clawson et al., 1955), it is recommended to extend the adaptation period when feeding a fiber-rich diet. As well as the adaptation period, pooling digesta samples is also believed to be more accurate by obtaining a more representative sample compared with single grab sample. Moughan et al. (1991) indicated that with the pooling of 5 daily grab samples, the precision of the dry matter (DM) digestibility approached that from total feces collection, and a 6-day composite fecal sample was as representative as the total fecal excretion based on the nutrients digestibility values. The same pattern was observed by Agudelo et al. (2010) in which the digestibility determined by IM increased from 1-day sample pooling through 5-day sample pooling, with the same trend for Cr2O3 excretion. Also based on the macronutrients digestibility, only 5-day sample pooling reached their plateaus and was similar with the value observed by TM. However, in the study of Jang et al. (2014), no consistently improved variation of digestibility was observed by the pooling of feces from 2 to 5-days. Similarly for an ileal digesta collection study, Kim et al. (2016) investigated the effects of collection time on flow of chromium and DM in growing pigs. Ileal digesta samples were collected in 2-h intervals from 08:00 to 20:00 during the collection day, where the samples from each 2-h collection periods represented one of the 6 samples from each pig. The results showed that the concentration of Cr in ileal digesta collected in every six 2-h periods exhibited a quadratic effect with an increasing and then decreasing trend. Compared with the 12-h collection, no differences were observed in the concentration of Cr and flow of DM from the ileal digesta samples that were collected over 6-, 8-, or 10-h periods. Hence it was concluded that 4 to 6 h of ileal sample collection starting 4 or 6 h after feeding may provide representative samples compared with samples collected from normal 12-h collection, which could reduce a considerable amount of labor. However, more studies from many laboratories are needed to verify the conclusion.

A number of studies have shown that the IM gave comparable digestibility values of components compared with TM (Jørgensen et al., 1984, Jagger et al., 1992). However, different results reported by other experiments indicate that the IM had lower estimated digestibility values than TM (Everts and Smits, 1987, Mroz et al., 1996, Jang et al., 2014), which was mainly due to the low recovery of markers (Mroz et al., 1996, Jang et al., 2014). Marker recovery is the proportion of marker intake from feed recovered in marker excretion in feces, which should be theoretically equal to 100%. However, it has been consistently reported that the recovery of markers is lower than 100% (Moughan et al., 1991, Jagger et al., 1992, Yin et al., 2000, Kavanagh et al., 2001), which may be due to the fineness of the marker leading to its retention by the gastrointestinal tract (Moore, 1957), as well as inaccurate sample collection and analysis.

4. Energy digestibility techniques in feedstuff evaluation

Energy utilized for maintenance and production represents the greatest proportion of feed cost (Noblet and Van Milgen, 2004). Because dietary energy concentration is also used to predict the voluntary feed intake and subsequently requirements for other nutrients, it is very essential to estimate the digestible energy value of feed ingredients and requirements of pigs precisely (Kil et al., 2013, Velayudhan et al., 2015). The energy system used to determine the energy contents and requirements for pigs has been reviewed in NRC (2012). Among digestible energy (DE), metabolizable energy (ME), and net energy (NE) system, the NE is generally assumed as the most ideal system to provide an available energy value for pigs (Kil et al., 2013). However, the DE and ME are currently more commonly used for evaluating feed ingredients and diets fed to pigs because they are relatively easier to determine (Kong and Adeola, 2014).

4.1. Energy digestibility: Direct and difference procedures

The direct procedure or difference procedure can be applied to determine the DE and ME of ingredients. Adeola and Kong (2014) determined the energy values of distillers dried grains with solubles and oilseed meals using the difference procedure. The results showed that the determined energy values of these ingredients are comparable to the previous published data. The coefficient of energy digestibility of the test ingredient in test diet can be calculated using Eq. (1). Table 1 shows for a pig, an example calculation of energy digestibility for test ingredient by the difference procedure using TM. It is notable that in Eq. (1), the Pti represents the proportional of energy contribution from test ingredient to the test diet rather than the test ingredient concentration in the test diet. The Pti is calculated as Pti = Eti/(Eti + Ebd), where Eti is the energy from the test ingredient in the test diet, Ebd is the energy from the basal diet in the test diet.

Table 1.

Example calculation of energy digestibility using the difference procedure.1

| Item | Basal diet (BD) | Test diet (TD) | Test ingredient (TI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TI concentration (Cti), g/kg | 0 | Cti = 150 | 1,000 |

| Energy yielding component, g/kg | Cbd = 9752 | 9753 | 1,000 |

| Gross energy (GE), kcal/kg | GEbd = 3,892 | GEtd = 4,016 | GEti = 5,065 |

| Dry matter (DM), % | DMbd = 87.23 | DMtd = 87.97 | DMti = 89.31 |

| GE DM basis, kcal/kg | 3,892/87.23 × 100 = 4,462 | 4,016/87.97 × 100 = 4,565 | 5,065/89.31 × 100 = 5,671 |

| Energy digestibility of diets | |||

| Feed intake (FI), kg/day | 0.956 | 0.754 | |

| DM of the diet | 0.87 | 0.88 | |

| DM intake, kg/day | 0.956 × 0.87 = 0.832 | 0.754 × 0.88 = 0.664 | |

| Gross energy intake (GEI), kcal/d | 0.832 × 4,462 = 3,710 | 0.664 × 4,565 = 3,030 | |

| Total weight of feces after drying at 55 °C, kg4 | 0.544 | 0.465 | |

| DM of feces, % | 0.91 | 0.94 | |

| Dry feces output, kg/d | (0.544 × 0.91)/5 = 0.099 | (0.465 × 0.94)/5 = 0.087 | |

| GE of feces, kcal/kg DM | 4,012 | 4,910 | |

| GE output in feces (GEO), kcal/d | 4,012 × 0.099 = 397 | 4,910 × 0.087 = 427 | |

| Energy digestibility of diet, % | 100 × (GEI – GEO)/GEI | ||

| Dbd = 100 × (3,710 – 397)/3,710 = 89.3 | Dtd = 100 × (3,030 – 427)/3,030 = 85.9 | ||

| Energy digestibility of TI | |||

| Energy from TI in TD (Eti), kcal | Eti = Cti × GEti/DMti/1,000 | ||

| 150 × 5,065/0.8931/1,000 = 851 | |||

| Energy from BD in TD (Ebd), kcal | Ebd = [(Cbd – Cti)/Cbd] × GEbd/DMbd | ||

| [(975 – 150)/975] × 3,892/0.8797 = 3,744 | |||

| The proportion of energy contribution from TI to TD (Pti) | Pti = Eti/(Eti + Ebd) | ||

| 851/(851 + 3744) = 0.185 | |||

| Energy digestibility of TI, % | Dbd + [(Dtd – Dbd)/Pti] | ||

| 89.3 + [(85.9 – 89.3)/0.185] = 70.9 | |||

Data were taken from Zhang and Adeola (unpublished data), which estimated the energy digestibility of full fat soybean by total collection method.

In the BD, corn, soybean meal, and soy oil were used as the sources of energy and accounts for 975 g/kg.

In the TD, the TI partly replace the energy sources in BD.

This represents feces weight after drying the 5-day collection at 55 °C in a forced-air oven.

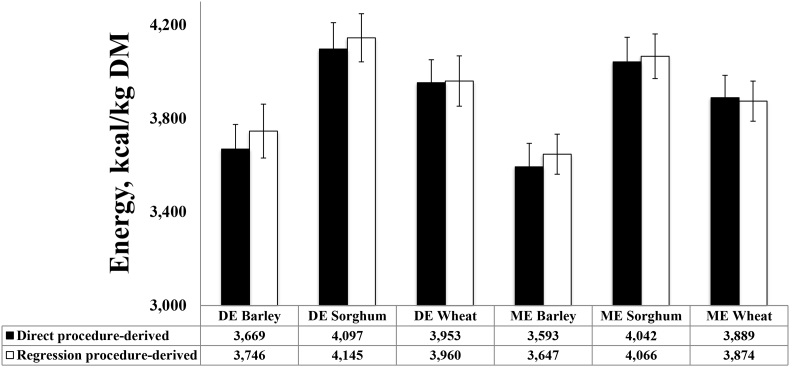

Another difference procedure, the regression procedure, has also been proven to be a reliable procedure to determine energy and nutrients digestibility (Fan and Sauer, 2002, Zhai and Adeola, 2013). In the regression procedure, a basal diet is fed to one group of pigs, and at least 2 test diets are fed to other pigs, with energy component in the basal diet being partially replaced by 2 levels of the test ingredient feed. The coefficient of energy digestibility of the test ingredient in each test diet can be calculated using Eq. (1); then test ingredient associated DE intake in kilocalories can be calculated and regressed against kilograms of test ingredient intake for pigs to generate intercepts and slopes, where the slope is the DE in kcal/kg of DM of test ingredients (Bolarinwa and Adeola, 2012). The regression procedure was compared with direct procedure by Bolarinwa and Adeola (2016), where 3 experiments were conducted to determine the energy values of barley, sorghum, and wheat for pigs using both direct and regression procedures. The results showed that the DE and ME of all the ingredients obtained using the direct procedure were not different from those obtained using the regression procedure. The corresponding DE derived by the direct procedure and regression procedure were 3,669 and 3,746 kcal/kg DM of barley, 3,593 and 3,647 kcal/kg DM of sorghum, and 3,533 and 3,590 kcal/kg DM of wheat, respectively (Fig. 1). Hence, it is concluded that using total collection method in regression procedure is as robust as the direct procedure.

Fig. 1.

Direct procedure-derived and regression procedure-derived digestible energy (DE) and metabolizable energy (ME) values of barley, sorghum, and wheat for pigs adapted from Bolarinwa and Adeola (2016). Values are means ± SD. The direct procedure-derived DE or ME values of all the ingredients were not different from regression procedure-derived DE or ME.

4.2. Energy digestibility: Total collection and index methods

Both TM and IM are widely applied to determine the total tract energy digestibility. Studies have compared the total tract energy digestibility determined by IM and TM. In the study of Clawson et al. (1955) the results indicated a higher variations in the IM measured digestibility of low digestible components such as crude fiber, but comparatively smaller variation in highly digestible components including DM and crude protein (CP). This may be because the fecal excretion pattern of marker was different to that of crude fiber, which lead to an inconsistency in the excretion pattern between Cr2O3 and the fiber compound, but a similar pattern with DM and CP. Hence, the different passage rates in excretion between marker and fiber in the GIT may affect the energy digestibility (Moore, 1957, Jang et al., 2014). Wang et al. (2016) investigated how indigestible markers and dietary fiber could influence the apparent total tract digestibility of energy. In the experiment, each diet contained 3 indigestible markers: Cr2O3, TiO2, and AIA, and the apparent total tract digestibility (ATTD) of energy was determined by both TM and IM. The results showed that the ATTD of energy determined by TM was greater than those determined by IM regardless of marker type. For the comparison among markers, interaction was observed between the marker type and fiber type for the ATTD of energy. The ATTD of energy in corn bran diet calculated by Cr2O3 was lower than that determined by TiO2, but for oat bran diet, the ATTD of energy calculated by AIA was greater than that determined by TiO2. A similar study was conducted to compare TM and IM, using the markers Cr2O3, TiO2, and AIA as well, for determining the energy values of full fat soybean (FFS) using the regression procedure (Zhang and Adeola, unpublished data). The results showed that the DE of FFS using TM was not different from those obtained from Cr2O3 and AIA, but higher than the DE value obtained from TiO2. These results indicated that IM is as robust as TM to determine ATTD of energy, but the accuracy may be marker-dependent.

In some situations, in order to correct positive nitrogen balance, the ME is converted to a N equilibrium basis for comparative purposes (Velayudhan et al., 2015). When AA are activated for providing energy purpose, the energy that is deposited in AA in mature animals cannot be completely oxidized by animals, and the ME value can be corrected to N equilibrium using the correction coefficient of 7.45 kcal/g of N retention (Adeola and Kong, 2014).

| MEn (kcal/kg) = ME − (7.45 × NR) | (3) |

where MEn is N-corrected ME; NR is N retention, g/kg DMI. However, because growing pigs do not usually use the retained protein for energy purpose, the correction to N equilibrium may not be necessary.

5. Amino acid digestibility techniques in feedstuff evaluation

Because the small intestine is the primary organ responsible for AA digestion and absorption, as well as to avoid the influence of hindgut fermentation on AA metabolism, ileal digestibility is preferred to estimate AA bioavailability of feed ingredients (Stein et al., 2007a). Hence, digesta sample from the end of ileum, rather than feces, is collected for AA digestibility determination.

5.1. Amino acid digestibility: Apparent and standardized ileal digestibility

Because the apparent ileal digestibility (AID) of AA does not differentiate the AA of dietary and endogenous origins in the ileal digesta, the inclusion level of test ingredients that supply AA in the test diet could affect the AID values determined using the direct procedure, especially for low protein feed ingredients (Stein et al., 2005). This is mainly because when the diet has a low AA concentration with a low total flow of AA in the digestive tract, the ileal endogenous losses of AA (IAA) contributes a relatively high proportion of AA compared with diets with low AA concentration in test ingredient, which leads to a low calculated values for AID of AA in feed ingredients in the low inclusion of AA in diet (Stein et al., 2005, Zhai and Adeola, 2011, Xue et al., 2014). As a result, the use of AID may underestimate the value of the mixed diet when it contains the low-CP ingredients, which may violate the additivity assumption in mixed diets containing a variety of ingredients (Stein et al., 2005, Kong and Adeola, 2014).

The ileal digesta contain unabsorbed dietary origin AA and endogenous AA, including basal IAA and specific IAA. The basal IAA represents the minimum quantities of AA that will be lost from the animal regardless of the diet. And the specific IAA represent the losses that are induced by feed ingredient composition (Stein et al., 2007a, Stein et al., 2007b, Adeola et al., 2016). By correcting AID values for total (basal plus specific IAA) or basal IAA, true ileal digestibility (TID) or standardized ileal digestibility (SID) of AA can be calculated, respectively. Because of the expensive procedure and difficulty to completely distinguish specific IAA from the undigested dietary AA, limited information of total IAA is available for a wide range of pig feed ingredients (Stein et al., 2007a, Adeola et al., 2016). Therefore, the SID is widely used to estimate the AA digestibility of feed ingredients. Jansman et al. (2002) summarized the different methods to estimate the basal IAA. Feeding a nitrogen-free diet (NFD) is the most common method to determine basal IAA (Adeola et al., 2016). Studies have been conducted to investigate the factors that could affect the basal IAA. Some data showed that the NFD with varied cellulose content from 30 to 80 g/kg had no effects on the basal ileal endogenous CP flow (Taverner et al., 1981, De Lange et al., 1989), which is consistently observed that no significant difference was observed on the basal IAA amounted NFD diets containing 30 to 120 g/kg wood cellulose (Leterme et al., 1992). However, the isolated fiber-rich fractions from wheat bran and sunflower meal were shown to increase the ileal flow of endogenous N compared with the purified cellulose of NFD (Schulze, 1994). Therefore, the type of the fiber rather than the fiber concentration may affect endogenous N losses in pigs when using NFD.

5.2. Amino acid digestibility: Total collection and index methods

Although TM is been considered as a reference method to determine the digestibility because all the outputs are technically collected, it is a challenge to conduct total collection of ileal digesta to determine the ileal digestibility. The available techniques for total collection of ileal digesta usually requires the technique of post-valve T-cecal (PVTC) cannulation to excise the cecum or the whole large intestine (Leeuwen et al., 1991, Moughan and Miner-Williams, 2013), which definitely affects the physiological condition of pigs. This technique is dependent on the assumption that with the high pressure in the abdomen, the digesta can be completely collected during the sampling time (Danfaer and Fernández, 1999). Re-entrant cannulation is also used as a reliable technique for ileal digesta total collection by inserting an ileo-cecal cannula and diverting the flow of digesta outside the body for collection (Leeuwen et al., 1988). Although these techniques have been thought to give reliable nutrient digestibility by allowing the total ileal digesta sample collection, the potential effects on the normal processes of digestion and absorption, the complex and expensive surgical procedures, and the risk of cannula blockage make them less used currently to determine the ileal digestibility (Sauer and Ozimek, 1986, Darcy-Vrillon and Laplace, 1990).

The combination of index method with T-cannula is considered as a reliable and most common alternative method to determine ileal digestibility currently (Stein et al., 2007a). Implanting simple T-cannula at the distal ileum, which avoids surgical removal of parts of intestinal tract, is considered as the least invasive to animals. This technique is based on the assumption that the sample obtained can represent the total flow of digesta during the whole experimental period. However, Moughan and Miner-Williams (2013) suggested that when cannula is opened, there is a change in pressure at the base of the cannula that may lead to a separation of the coarse and fine particles, especially in fiber-rich diets. It has also been reported that compared with PVTC and re-entrant cannula, using Cr2O3 and simple T-cannula gave a higher digestibility coefficient for N and AA, which may be due to a separation between markers and digesta contents, especially for fiber components (Just et al., 1985, Köhler et al., 1990).

Several studies have indicated that the choice of indigestible markers could affect the AID or SID of AA, as well as the endogenous losses of AA. Favero et al. (2014) showed that the basal IAA of AA determined by Cr2O3 was lower than that determined by AIA or TiO2, and the AID of N and AA in SBM calculated by AIA tended to be lower than that determined by Cr2O3 or TiO2. Fan and Sauer (2002) also reported similar results that the digestibility markers, Cr2O3 or AIA had a considerable effect on the CP and AA digestibility in fiber-rich diets. The ileal CP and AA digestibility coefficients determined by Cr2O3 were consistently higher than the values determined by AIA, which was explained by the author as possible separation between the markers and sample components as Cr2O3 mainly represents the liquid phase of the digesta and contained soluble fractions of the diets which has higher CP and AA digestibility, and AIA mainly represents the cell wall components of the diets in the digesta which is lower in CP and AA digestibility. However, this may only occur in fiber-rich diets. Van Leeuwen et al. (1996) that there were no differences in the ileal nutrient digestibility coefficients between the Cr2O3 and the AIA using simple T-cannula in which the experimental diets were not high in fiber. Hence, it was suggested by Fan and Sauer (2002) that in fiber-rich diets, dual digestibility markers should be used to measure ileal AA digestibility coefficients.

Researchers also looked at whether the marker concentration may affect the determined AA digestibility values. In the study of Jagger et al. (1992), pigs were fed 4 barley-wheat-based diets, which consisted of 1 or 5 g/kg of Cr2O3, and 1 or 5 g/kg of TiO2. The results showed that 5 g/kg of Cr2O3 and TiO2 treatment were associated with slightly slower rates of feed consumption under a restricted feeding program, which disappeared following acclimatization. In addition, the result indicated that the treatment of 1 g/kg Cr2O3 had consistently lower values and higher standard errors of apparent ileal N and single AA digestibility compared with other treatments. Olukosi et al. (2012) reported the results of an experiment designed to test whether different marker or marker concentration in corn-soybean meal diets influence apparent ileal AA digestibility in pigs. The result showed that 2 commonly used concentrations (0.3% and 0.5%) for Cr2O3 and TiO2 had no effect on apparent ileal AA digestibility values.

5.3. Potential issues in the determination of AA digestibility

It is obvious that feeding a NFD may affect the normal body protein metabolism. In addition, due to the lack of the stimulatory effect on endogenous gut protein secretions, the basal IAA at the distal ileum may be underestimated using a NFD (Stein et al., 2007a, Adeola et al., 2016). Hence, feeding a diet containing a highly digestible protein source may be an alternative method. The validity of this method depends on the assumption that the true digestibility of AA in highly digestible protein source is really 100%. Park et al. (2016) determined the TID of AA digestibility of casein using the regression procedure. The estimated TID of CP, Lys, Met, Thr, and Trp were 101%, 99.9%, 99.2%, 97.0%, and 98.8%, respectively, which validated the assumption that the digestibility of most of the AA in casein are close to 100%. Using this method, Fuller and Cadenhead (1991) reported a lower IAA in pigs fed a low-casein diet compared with the purified NFD. However, Leibholz (1982) found similar values for IAA in low-casein and protein-free diets fed to growing pigs.

In addition to the concern for the basal IAA determination, there is a similar concern for AA experimental diets where the assay feed ingredient is the only AA source in a cornstarch-based or dextrose based diet when using the direct procedure. These experimental diets may not provide each dietary AA to satisfy the optimal AA ratio with only one feed ingredient, and may affect the AA digestion and absorption because of the AA imbalance (Lewis, 2001). Park et al. (2016) determined the SID of AA in distillers’ dried grains with solubles (DDGS) using 2 isonitrogenous experimental diets: one was formulated using DDGS as the sole source of N in the diet, and another diet was formulated using both DDGS and casein as the N source with a more balanced AA ratio. The determined AID and SID of Arg, Lys, Phe, and Trp in the diet that only contained DDGS were less than those determined in the DDGS and casein diet, and the SID of CP, His, and Ile in the DDGS diet were also lower than those in the DDGS and casein diet. The results showed that an improved AA ratio in the experimental diets by including highly digestible protein casein could affect the SID of CP and AA in test feed with poorer protein quality. Hence, more studies are needed to investigate how the basal diet may affect the IAA, and AA digestibility.

6. Phosphorus and calcium digestibility techniques in feedstuff evaluation

Phosphorus and Ca are the most abundant mineral elements in an animal's body, with more than 80% of P and 90% of Ca found in the skeleton. Both P and Ca are needed for bone and teeth formation and for many other physiological functions in the body (Crenshaw, 2001). It is very important to provide P and Ca in an optimal ratio to maximize the utilization of these 2 minerals.

Generally, there are 2 categories of P and Ca sources in feed ingredients: organic sources including plant origin and animal origin, and inorganic sources. Both animal origin and inorganic sources have a considerable amount of highly digestible P and Ca. In plant sources, P is stored primarily in the form of phytate with low digestibility, and Ca concentration is very low with 0.03% in corn and 0.4% in SBM (NRC, 2012). In recent years, efforts have been made to estimate the P and Ca digestibility in these ingredients using various methods. Two main questions about P and Ca digestibility are: whether ileal digestibility or total tract digestibility should be determined, and whether the apparent digestibility should be corrected for endogenous losses of P and Ca to determine standardized total tract digestibility (STTD) or true total tract digestibility (TTTD).

6.1. Phosphorus and calcium digestibility: Ileal digestibility vs. total tract digestibility

Avoiding the influence of microbial fermentation on AA in the hindgut of pigs necessitates the use of ileal digestibility rather total tract digestibility of AA (Sauer and Ozimek, 1986). For P, it has been reported that there is no difference between ileal and total tract digestibility of P, and the net absorption or excretion in the large intestine does not affect the overall digestion of P (Fan et al., 2001, Ajakaiye et al., 2003, Bohlke et al., 2005, Dilger and Adeola, 2006, Zhang et al., 2016). Similar results of no difference between the AID and ATTD of Ca in corn, soybean meal, and canola meal diets, as well as in diets using the inorganic sources of Ca have been reported (Bohlke et al., 2005, González-Vega et al., 2013, Zhang et al., 2016). Considering that it is less expensive and laborious, it is recommended to determine total tract digestibility for both P and Ca digestibility using TM.

6.2. Phosphorus and calcium digestibility: Apparent, standardized, and true total tract digestibility

Among ATTD, STTD, and TTTD, the ATTD of P or Ca is easiest to calculate by simply measuring the total intake of P or Ca and subtracting the fecal output of P or Ca. However, based on previous experience in AA, the use of apparent digestibility brings some challenges including ingredient-inclusion level dependent digestibility value and non-additivity. It is reasonable to consider that the same challenges may occur to ATTD of P and Ca. Petersen and Stein (2006) showed that the increasing inclusion rate of monocalcium phosphate did not change the ATTD values of P in monocalcium phosphate. In addition, Akinmusire and Adeola (2009) reported that the inclusion level of SBM or canola meal did not affect the ATTD of P of test ingredients either. However, Dilger and Adeola (2006) reported linear and quadratic effects of inclusion level of test ingredient on the ATTD of P of conventional SBM, but not in low-phytate SBM.

With Ca digestibility, it has been reported in several studies that the dietary Ca concentration supplemented from inorganic Ca sources did not affect the ATTD of Ca (Stein et al., 2011, Zhang et al., 2016). Whereas, Gonzá;lez-Vega et al. (2013) showed that when canola meal was used as the sole dietary Ca source, the inclusion level of canola meal linearly increased the ATTD of Ca. Thus, dietary levels of inorganic sources do not appear to affect ATTD of P and Ca, but it may not always the same case for organic sources of P and Ca. Another concern for application of ATTD of P and Ca is that additivity assumption in mixed diets may not hold. Fan and Sauer (2002) reported that the ATTD of P in barley, wheat, peas, and canola meal were not always additive in a mixed diet for pigs. In addition, Zhang and Adeola (2017) showed that there is a trend that ATTD of Ca determined for limestone and dicalcium phosphate were not additive in the limestone and dicalcium phosphate mixed semi-purified diet. As with AA, the contribution of endogenous losses of P or Ca to the total intestinal flow of P or Ca is relatively greater in diets with low concentrations of P or Ca compared with diets with higher concentrations of P or Ca. As a result, the ATTD of P and Ca is underestimated for diets containing low concentrations of P and Ca. Therefore, the use of ATTD obtained in ingredients containing a low concentration of P or Ca to calculate the ATTD of a mixed diet containing high concentration of P or Ca may underestimate the ATTD in the mixed diet (Stein et al., 2005, González-Vega et al., 2013, Zhai and Adeola, 2013, Xue et al., 2014).

To overcome these problems, the STTD and TTTD should be used as an alternative of ATTD. Fang et al. (2007) estimated the TTTD of P of different organic ingredients using the difference procedure, and the results proved the additivity of TTTD values for P. In addition, Zhai and Adeola (2013) estimated the TTTD of P in corn and SBM, and showed that the values for the TTTD of P were additive in a corn-SBM based diet. For Ca digestibility, Zhang and Adeola (2017) estimated the TTTD of Ca in limestone and dicalcium phosphate using the regression procedure, the result also showed that the TTTD of Ca are additive in semi-purified diets. Hence, correcting the endogenous losses of P and Ca from ATTD provide more accurate data for P and Ca digestibility.

In this review, the endogenous losses of P and Ca estimation reported in the literature are summarized and listed in Table 2, Table 3. This summary provides determination procedure, mean BW of pigs, and estimates of endogenous losses of P and Ca. In summary, the endogenous losses of P range from 8 to 455 mg/kg of DM intake, and a range of 156 to 329 mg/kg of DM intake for endogenous losses of Ca. More data are available for P, and there is a greater variance for the determined endogenous losses of P compared with Ca. For P, the endogenous losses determined by the regression procedure has an even higher variance than the values determined by P-free diet. For regression procedure, the higher variance may be due to the different experimental diets used to determine the endogenous losses of P. For example, the endogenous losses of P determined from canola meal based diets were much lower than that from SBM based diets (Akinmusire and Adeola, 2009). However, the commonly used P-free diets are more uniform because they are normally formulated with highly digestible ingredients such as cornstarch, dextrose, and highly digestible protein sources. Further studies are needed to identify the factors that could affect the endogenous losses of P.

Table 2.

Summary of estimation of endogenous losses of phosphorus (P) in growing pigs.1

| Reference | Diet composition | Average BW, kg | Endogenous losses of P, mg/kg DMI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regression procedure | |||

| Akinmusire and Adeola (2009) | Canola-cornstarch2 | 17 | 101 |

| Canola-cornstarch3 | 17 | 38 | |

| Akinmusire and Adeola (2009) | SBM-cornstarch2 | 17 | 48 |

| SBM-cornstarch3 | 17 | 8 | |

| Ajakaiye et al. (2003) | SBM-cornstarch | 49 | 445 |

| Dilger and Adeola (2006) | SBM-cornstarch | 31 | 208 |

| Dilger and Adeola (2006) | Low-phytase SBM-cornstarch | 31 | 145 |

| Fan et al. (2001) | SBM-cornstarch | 6.8 | 250 |

| P-free diet | |||

| Almeida and Stein (2012) | Gelatin-cornstarch | 18 | 206 |

| Almeida and Stein (2010) | Gelatin-cornstarch | 14 | 199 |

| Petersen and Stein (2004) | Gelatin-cornstarch | 53 | 139 |

| Son et al. (2013) | Gelatin-cornstarch | 40 | 252 |

| Son and Kim (2015) | Gelatin-cornstarch | 50 | 185 |

SBM = soybean meal.

Endogenous losses of Calcium (Ca) presented in mg/d from the reference was transformed to mg/kg DMI by using the average daily DM intake across all the treatments.

Without phytase.

With phytase.

Table 3.

Summary of estimation of endogenous losses of Ca in growing pigs.1

| Reference | Diet composition | Average BW, kg | Endogenous losses of Ca, mg/kg DMI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regression procedure | |||

| Zhang and Adeola (2017) | Corn-CGM-cornstarch2 | 20 | 206 |

| González-Vega et al. (2013) | Canola meal-cornstarch3 | 16 | 160 |

| González-Vega et al. (2013) | Canola meal-cornstarch4 | 16 | 189 |

| Ca-free diet | |||

| Merriman and Stein (2016) | Corn-potato protein isolate | 9 | 329 |

| González-Vega et al. (2015) | Fish meal-cornstarch | 19 | 156 |

| González-Vega et al. (2015) | Fish meal-corn-corn germ | 19 | 168 |

Endogenous losses of Ca presented in mg/d from the reference was transformed to mg/kg DMI by using the average daily DM intake across all the treatments.

Corn-corn gluten meal-cornstarch.

Without phytase.

With phytase.

6.3. Potential issues in phosphorus and calcium digestibility determination

When test ingredients are evaluated for P and Ca digestibility, other dietary factors, such as N concentration, is generally not considered. However, as indicated in NRC (2012), the whole body P contents of the pig is correlated to the whole body N contents of the pig. Hence there may be a potential relationship between the absorption and retention of N and P. It has been reported in chickens that CP deficiency decreased the pre-cecal P digestion in broiler chickens (Xue et al., 2016). A parallel study was conducted in pigs where the results showed that the estimated TTTD of P in monocalcium phosphate were 80.5%, 82.6%, and 87.9% under 5.5%, 9.7%, and 13.9% CP diets, respectively. Although the values were not statistically different, the difference in determined values also infers that dietary CP deficiency may constrain P digestion (Xue et al., 2017). Hence, the protein supplementation in basal diets may be required to alleviate the effect of protein deficiency on P digestion during P digestibility studies for feed ingredients. For Ca digestibility, González-Vega et al. (2015) reported that the basal diet could affect the values of the ATTD and STTD of Ca in fish meal. The determined ATTD and STTD of Ca in fish meal were greater in corn-based diets than in cornstarch-based diets, which may be due to the differences in soluble dietary fiber concentrations between the 2 basal diets and changes in intestinal motility and digesta passage rate (González-Vega et al., 2015).

7. Conclusion

Methodologies to determine the digestibility of energy and nutrients for swine include the combination between direct or different procedures and TM or IM, Careful selection should be based on the component of interest, feed ingredients, and available laboratory facilities. For energy, P, and Ca, total tract digestibility rather than ileal digestibility should be determined. Consequently, the combination of TM and direct procedure or regression procedure is suggested to give more accurate digestibility data. For AA however, ileal digestibility rather than total tract digestibility using a combination of IM and direct procedure is the suggested reliable technique. In addition, it is necessary to correct apparent digestibility for endogenous losses because standardized or true digestibility provides more accurate estimation for the feed ingredients as well as values that are additive in diet formulation. Further investigation is needed to consider about how other components could affect the digestibility of the components of interest, and how to optimize the basal diet when using the direct procedure. Additionally, methods to determine endogenous losses of nutrients should be investigated further to give more comparable values among different experiments.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

References

- Adeola O., Young L.G., McMillan E.G., Moran E.T., Jr. Comparative availability of amino acids in OAC winter triticale and corn for pigs. J Anim Sci. 1986;63:1862–1869. [Google Scholar]

- Adeola O. Digestion and balance techniques in pigs. In: Lewis A.J., Southern L.L., editors. Swine nutrition. 2nd ed. CRC Press; Washington, DC: 2001. pp. 903–916. [Google Scholar]

- Adeola O., Kong C. Energy value of distillers dried grains with solubles and oilseed meals for pigs. J Anim Sci. 2014;92:164–170. doi: 10.2527/jas.2013-6662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adeola O., Xue P., Cowieson A., Ajuwon K. Basal endogenous losses of amino acids in protein nutrition research for swine and poultry. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2016;221:274–283. [Google Scholar]

- Agudelo J., Lindemann M., Cromwell G. A comparison of two methods to assess nutrient digestibility in pigs. Livest Sci. 2010;133:74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Ajakaiye A., Fan M., Archbold T., Hacker R., Forsberg C., Phillips J. Determination of true digestive utilization of phosphorus and the endogenous phosphorus outputs associated with soybean meal for growing pigs. J Anim Sci. 2003;81:2766–2775. doi: 10.2527/2003.81112766x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akinmusire A., Adeola O. True digestibility of phosphorus in canola and soybean meals for growing pigs: influence of microbial phytase. J Anim Sci. 2009;87:977–983. doi: 10.2527/jas.2007-0778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida F., Stein H.H. Performance and phosphorus balance of pigs fed diets formulated on the basis of values for standardized total tract digestibility of phosphorus. J Anim Sci. 2010;88:2968–2977. doi: 10.2527/jas.2009-2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida F., Stein H.H. Effects of graded levels of microbial phytase on the standardized total tract digestibility of phosphorus in corn and corn coproducts fed to pigs. J Anim Sci. 2012;90:1262–1269. doi: 10.2527/jas.2011-4144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P., Kerr B., Weber T., Ziemer C., Shurson G. Determination and prediction of digestible and metabolizable energy from chemical analysis of corn coproducts fed to finishing pigs. J Anim Sci. 2012;90:1242–1254. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-3605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlke R., Thaler R., Stein H.H. Calcium, phosphorus, and amino acid digestibility in low-phytate corn, normal corn, and soybean meal by growing pigs. J Anim Sci. 2005;83:2396–2403. doi: 10.2527/2005.83102396x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolarinwa O., Adeola O. Energy value of wheat, barley, and wheat dried distillers grains with solubles for broiler chickens determined using the regression method. Poult Sci. 2012;91:1928–1935. doi: 10.3382/ps.2012-02261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolarinwa O., Adeola O. Regression and direct methods do not give different estimates of digestible and metabolizable energy values of barley, sorghum, and wheat for pigs. J Anim Sci. 2016;94:610–618. doi: 10.2527/jas.2015-9766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clawson A., Reid J., Sheffy B., Willman J. Use of chromium oxide in digestion studies with swine. J Anim Sci. 1955;14:700–709. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw T.D. Calcium, phosphorus, vitamin D, and vitamin K. In: Lewis A.J., Southern L.L., editors. Swine nutrition. 2nd ed. CRC Press; Washington, DC: 2001. pp. 187–212. [Google Scholar]

- Danfaer A., Fernández J.A. Developments in the prediction of nutrient availability in pigs: a review. Acta Agric Scand. 1999;49:73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Darcy-Vrillon B., Laplace J. Digesta collection procedure may affect ileal digestibility in pigs fed diets based on wheat bran or beet pulp. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 1990;27:307–316. [Google Scholar]

- De Lange C., Sauer W., Mosenthin R., Souffrant W. The effect of feeding different protein-free diets on the recovery and amino acid composition of endogenous protein collected from the distal ileum and feces in pigs. J Anim Sci. 1989;67:746–754. doi: 10.2527/jas1989.673746x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilger R., Adeola O. Estimation of true phosphorus digestibility and endogenous phosphorus loss in growing pigs fed conventional and low-phytate soybean meals. J Anim Sci. 2006;84:627–634. doi: 10.2527/2006.843627x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everts H., Smits B. Effect of crude fibre, feeding level, body weight and method of measuring on apparent digestibility of compound feed by sows. World Rev Anim Prod. 1987;4:40. [Google Scholar]

- Fan M.Z., Sauer W.C. Determination of apparent ileal digestibility in barley and canola meal for pigs with the direct, difference, and regression methods. J Anim Sci. 1995;73:2364–2374. doi: 10.2527/1995.7382364x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan M.Z., Sauer W.C. Determination of true ileal amino acid digestibility and the endogenous amino acid outputs associated with barley samples for growing-finishing pigs by the regression analysis technique. J Anim Sci. 2002;80:1593–1605. doi: 10.2527/2002.8061593x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan M.Z., Archbold T., Sauer W.C., Lackeyram D., Rideout T., Gao Y. Novel methodology allows simultaneous measurement of true phosphorus digestibility and the gastrointestinal endogenous phosphorus outputs in studies with pigs. J Nutr. 2001;131:2388–2396. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.9.2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang R., Li T., Yin F., Yin Y., Kong X., Wang K. The additivity of true or apparent phosphorus digestibility values in some feed ingredients for growing pigs. Asian Australas J Anim Sci. 2007;20:1092. [Google Scholar]

- Favero A., Ragland D., Vieira S., Owusu-Asiedu A., Adeola O. Digestibility marker and ileal amino acid digestibility in phytase-supplemented soybean or canola meals for growing pigs. J Anim Sci. 2014;92:5583–5592. doi: 10.2527/jas.2014-7919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton T., Fenton M. An improved procedure for the determination of chromic oxide in feed and feces. Can J Anim Sci. 1979;59:631–634. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller M., Cadenhead A. Effect of the amount and composition of the diet on galactosamine flow from the small intestine. In: Verstegen M.W.A., Huisman J., Den Hartog L.A., editors. Proceedings of the Vth international symposium on digestive physiology in pigs. Pudoc; Wageningen: 1991. pp. 330–333. EAAP Publication No. 54. [Google Scholar]

- González-Vega J., Walk C., Liu Y., Stein H.H. Determination of endogenous intestinal losses of calcium and true total tract digestibility of calcium in canola meal fed to growing pigs. J Anim Sci. 2013;91:4807–4816. doi: 10.2527/jas.2013-6410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Vega J., Walk C., Stein H.H. Effect of phytate, microbial phytase, fiber, and soybean oil on calculated values for apparent and standardized total tract digestibility of calcium and apparent total tract digestibility of phosphorus in fish meal fed to growing pigs. J Anim Sci. 2015;93:4808–4818. doi: 10.2527/jas.2015-8992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagger S., Wiseman J., Cole D., Craigon J. Evaluation of inert markers for the determination of ileal and faecal apparent digestibility values in the pig. Br J Nutr. 1992;68:729–739. doi: 10.1079/bjn19920129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang Y.D., Lindemann M.D., Agudelo-Trujillo J.H., Escobar C.S., Kerr B.J., Inocencio N. Comparison of direct and indirect estimates of apparent total tract digestibility in swine with effort to reduce variation by pooling of multiple day fecal samples. J Anim Sci. 2014;92:4566–4576. doi: 10.2527/jas.2013-6570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansman A., Smink W., Van Leeuwen P., Rademacher M. Evaluation through literature data of the amount and amino acid composition of basal endogenous crude protein at the terminal ileum of pigs. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2002;98:49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Just A., Jørgensen H., Fernández J. Correlations of protein deposited in growing female pigs to ileal and faecal digestible crude protein and amino acids. Livest Prod Sci. 1985;12:145–159. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen H., Sauer W.C., Thacker P.A. Amino acid availabilities in soybean meal, sunflower meal, fish meal and meat and bone meal fed to growing pigs. J Anim Sci. 1984;58:926–934. [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh S., Lynch P., O’mara F., Caffrey P. A comparison of total collection and marker technique for the measurement of apparent digestibility of diets for growing pigs. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2001;89:49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kil D., Kim B., Stein H.H. Feed energy evaluation for growing pigs. Asian Australas J Anim Sci. 2013;26:1205. doi: 10.5713/ajas.2013.r.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B.G., Liu Y., Stein H.H. Effects of collection time on flow of chromium and dry matter and on basal ileal endogenous losses of amino acids in growing pigs. J Anim Sci. 2016;94:4196–4204. doi: 10.2527/jas.2015-0248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong C., Adeola O. Evaluation of amino acid and energy utilization in feedstuff for swine and poultry diets. Asian Australas J Anim Sci. 2014;27:917–925. doi: 10.5713/ajas.2014.r.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler T., Huisman J., Den Hartog L.A., Mosenthin R. Comparison of different digesta collection methods to determine the apparent digestibilities of the nutrients at the terminal ileum in pigs. J Sci Food Agr. 1990;53:465–475. [Google Scholar]

- Lammers P., Kerr B., Weber T., Dozier W., Kidd M., Bregendahl K. Digestible and metabolizable energy of crude glycerol for growing pigs. J Anim Sci. 2008;86:602–608. doi: 10.2527/jas.2007-0453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeuwen P.V., Kleef D.V., Kempen G.V., Huisman J., Verstegen M. The post valve T-Caecum cannulation technique in pigs applicated to determine the digestibility of amino acid in maize, groundnut and sunflower meal. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 1991;65:183–193. [Google Scholar]

- Leeuwen P.V., Sauer W., Huisman J., Kleef D.V., Hartog L. Ile-cecal re-entrant cannulation in baby pigs. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 1988;59:59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Leibholz J. Utilization of casein, fish meal and soya bean proteins in dry diets for pigs between 7 and 28 days of age. Anim Prod. 1982;34:9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Leterme P., Pirard L., Thewis A. A note on the effect of wood cellulose level in protein-free diets on the recovery and amino acid composition of endogenous protein collected from the ileum in pigs. Anim Prod. 1992;54:163–165. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis A.J. Amino acids in swine nutrition. In: Lewis A.J., Southern L.L., editors. Swine nutrition. 2nd ed. CRC Press; Washington, DC: 2001. pp. 131–150. [Google Scholar]

- Liu P., Souza L., Baidoo S., Shurson G. Impact of distillers dried grains with solubles particle size on nutrient digestibility, DE and ME content, and flowability in diets for growing pigs. J Anim Sci. 2012;90:4925–4932. doi: 10.2527/jas.2011-4604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriman L., Stein H.H. Particle size of calcium carbonate does not affect apparent and standardized total tract digestibility of calcium, retention of calcium, or growth performance of growing pigs. J Anim Sci. 2016;94:3844–3850. doi: 10.2527/jas.2015-0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore J. Diurnal variations in the composition of the faeces of pigs on diets containing chromium oxide. Br J Nutr. 1957;11:273–288. doi: 10.1079/bjn19570045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moter V., Stein H.H. Effect of feed intake on endogenous losses and amino acid and energy digestibility by growing pigs. J Anim Sci. 2004;82:3518–3525. doi: 10.2527/2004.82123518x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moughan P., Smith W., Schrama J., Smits C. Chromic oxide and acid-insoluble ash as faecal markers in digestibility studies with young growing pigs. New Zeal J Agr Res. 1991;34:85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Moughan P.J., Miner-Williams W. Determination of protein digestibility in the growing pig. In: Blachier F., Wu G., Yin Y., editors. Nutritional and physiological functions of amino acids in pigs. Springer; Vienna, Austria: 2013. pp. 251–271. [Google Scholar]

- Mroz Z., Bakker G., Jongbloed A., Dekker R., Jongbloed R., Van Beers A. Apparent digestibility of nutrients in diets with different energy density, as estimated by direct and marker methods for pigs with or without ileo-cecal cannulas. J Anim Sci. 1996;74:403–412. doi: 10.2527/1996.742403x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noblet J., Van Milgen J. Energy value of pig feeds: effect of pig body weight and energy evaluation system. J Anim Sci. 2004;82:229–238. doi: 10.2527/2004.8213_supplE229x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NRC . 11th rev. ed. Natl. Acad. Press; Washington, DC: 2012. Nutrient requirements of swine. [Google Scholar]

- Olukosi O., Bolarinwa O., Cowieson A., Adeola O. Marker type but not concentration influenced apparent ileal amino acid digestibility in phytase-supplemented diets for broiler chickens and pigs. J Anim Sci. 2012;90:4414–4420. doi: 10.2527/jas.2011-4801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C.S., Fang C., Ragland D., Adeola O. Effects of casein on digestibility of amino acids in distillers dried grains with solubles fed to pigs. J Anim Sci. 2016;94(Suppl. 5):473. (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Petersen G., Stein H.H. Novel procedure for estimating endogenous losses and measurement of apparent and true digestibility of phosphorus by growing pigs. J Anim Sci. 2006;84:2126–2132. doi: 10.2527/jas.2005-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potkins Z., Lawrence T., Thomlinson J. Effects of structural and non-structural polysaccharides in the diet of the growing pig on gastric emptying rate and rate of passage of digesta to the terminal ileum and through the total gastrointestinal tract. Br J Nutr. 1991;65:391–413. doi: 10.1079/bjn19910100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer W.C., Ozimek L. Digestibility of amino acids in swine: results and their practical applications. A review. Livest Prod Sci. 1986;15:367–388. [Google Scholar]

- Schulze H. Wageningen Institute of Animal Sciences; 1994. Endogenous ileal nitrogen losses in pigs: dietary factors. [Doctor Degree Dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- Son A., Kim B. Effects of dietary cellulose on the basal endogenous loss of phosphorus in growing pigs. Asian Australas J Anim Sci. 2015;28:369. doi: 10.5713/ajas.14.0539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son A., Shin S., Kim B. Standardized total tract digestibility of phosphorus in copra expellers, palm kernel expellers, and cassava root fed to growing pigs. Asian Australas J Anim Sci. 2013;26:1609–1613. doi: 10.5713/ajas.2013.13517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein H.H., Pedersen C., Wirt A., Bohlke R. Additivity of values for apparent and standardized ileal digestibility of amino acids in mixed diets fed to growing pigs. J Anim Sci. 2005;83:2387–2395. doi: 10.2527/2005.83102387x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein H.H., Adeola O., Cromwell G., Kim S., Mahan D., Miller P. Concentration of dietary calcium supplied by calcium carbonate does not affect the apparent total tract digestibility of calcium, but decreases digestibility of phosphorus by growing pigs. J Anim Sci. 2011;89:2139–2144. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-3522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein H.H., Seve B., Fuller M., Moughan P., De Lange C. Board invited review: amino acid bioavailability and digestibility in pig feed ingredients: terminology and application. J Anim Sci. 2007;85:172–180. doi: 10.2527/jas.2005-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein H.H., Seve B., Fuller M., Moughan P., Sèved B., Mosenthin R. Invited review: amino acid bioavailability and digestibility in pig feed ingredients: terminology and application. Livest Sci. 2007;109:282–285. doi: 10.2527/jas.2005-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taverner M., Hume I., Farrell D. Availability to pigs of amino acids in cereal grains. Br J Nutr. 1981;46:149–158. doi: 10.1079/bjn19810017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Leeuwen P., Veldman A., Boisen S., Deuring K., Van Kempen G., Derksen G. Apparent ileal dry matter and crude protein digestibility of rations fed to pigs and determined with the use of chromic oxide (Cr2O3) and acid insoluble ash as digestive markers. Br J Nutr. 1996;76:551–562. doi: 10.1079/bjn19960062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velayudhan D., Kim I., Nyachoti C. Characterization of dietary energy in swine feed and feed ingredients: a review of recent research results. Asian Australas J Anim Sci. 2015;28:1–13. doi: 10.5713/ajas.14.0001R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Ragland D., Adeola O. Investigations of marker and fiber effects on energy and nutrient utilization in growing pigs. J Anim Sci. 2016;94(Suppl. 5):473. (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Xue P., Ragland D., Adeola O. Determination of additivity of apparent and standardized ileal digestibility of amino acids in diets containing multiple protein sources fed to growing pigs. J Anim Sci. 2014;92:3937–3944. doi: 10.2527/jas.2014-7815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue P., Ajuwon K.M., Adeola O. Phosphorus and nitrogen utilization responses of broiler chickens to dietary crude protein and phosphorus levels. Poult Sci. 2016;95:2615–2623. doi: 10.3382/ps/pew156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue P., Ragland D., Adeola O. Influence of dietary crude protein and phosphorus on ileal digestion of phosphorus and amino acids in growing pigs. J Anim Sci. 2017;95:1–9. doi: 10.2527/jas.2016.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y.L., McEvoy J., Schulze H., McCracken K. Studies on cannulation method and alternative indigestible markers and the effects of food enzyme supplementation in barley-based diets on ileal and overall apparent digestibility in growing pigs. Anim Sci. 2000;70:63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai H., Adeola O. Apparent and standardized ileal digestibilities of amino acids for pigs fed corn-and soybean meal-based diets at varying crude protein levels. J Anim Sci. 2011;89:3626–3633. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-3732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai H., Adeola O. True total-tract digestibility of phosphorus in corn and soybean meal for fifteen-kilogram pigs are additive in corn–soybean meal diet. J Anim Sci. 2013;91:219–224. doi: 10.2527/jas.2012-5295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Ragland D., Adeola O. Comparison of apparent ileal and total tract digestibility of calcium in calcium sources for pigs. Can J Anim Sci. 2016;96:563–569. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Adeola O. True total-tract digestibility of calcium in limestone and dicalcium phosphate for twenty-kilogram pigs are additive in a semi-purified diet. J Anim Sci. 2017;95(Suppl. 5):87. doi: 10.2527/jas2017.1849. (Abstract) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]