Abstract

Background:

Patency of the pedal-plantar arch limits risk of amputation in peripheral artery disease (PAD). We examined patients without chronic kidney disease (CKD)/diabetes mellits (DM) [PAD-control], those with DM without CKD, and those with CKD without DM.

Method:

Uni- and multivariate logistic regression was used to assess association of CKD with loss of patency of the pedal–plantar arch and presence of tibial or peroneal vessel occlusion. Multivariate models adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and smoking.

Results:

A total of 419 patients were included [age 75.2 ± 10.3 years, 288 (69%) male]. CKD nearly doubled the unadjusted odds ratio (OR) for loss of patency of the pedal–plantar arch. After adjustment, association remained significant for severe CKD [estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) ≤ 29 ml/min compared with eGFR ≥ 60 ml/min, adjusted (adj.) OR 8.24 (95% confidence interval {CI} 0.99–68.36, p = 0.05)]. CKD was not related to risk of tibial or peroneal artery occlusion [PAD-control versus CKD, adj. OR 1.09 (95% CI 0.49–2.44, p = 0.83)] in contrast to DM [PAD–control versus DM, adj. OR 2.41 (95% CI 1.23–4.72, p = 0.01), CKD versus DM, adj. OR 2.21 (95% CI 0.93–5.22); p = 0.07)].

Conclusions:

Below the knee (BTK) vascular pattern differs in patients with either DM or CKD alone. Severe CKD is a risk factor for loss of patency of the pedal–plantar arch.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, peripheral arterial disease

Introduction

Lower limb peripheral artery disease (PAD) is a common comorbidity in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) and chronic kidney disease (CKD).1–3 Atherosclerotic disease pattern in PAD is influenced by cardiovascular risk factors.4,5 CKD and DM are known to be the leading cause for vascular calcification and share similar pathomorphological aspects.6 DM was shown to be a significant predictor for below the knee (BTK) artery involvement5 and small vessel disease defined as the highest 10% of toe brachial index decline with limited ankle brachial index.4 Major cardiovascular disease trials frequently exclude patients with CKD and do not provide adequate information on renal function of enrollees or effect of interventions on patients with CKD without DM.7

DM and CKD are associated with critical limb ischemia (CLI)8–10 that goes along with a high rate of minor and major amputations.11,12 The importance of patency of the pedal–plantar arch on the rate of amputations was suggested in early series derived from patients with DM13 or end stage renal disease (ESRD).14 It is rather more recently that patency of the pedal–plantar arch as well as obstructive burden of pedal arteries has become a dedicated focus of interest for the understanding of poor clinical limb outcome after distal bypass or endovascular treatment.3,15–19

Kidney disease is a frequent complication in DM.20 Differentiation between DM and CKD as leading risk factors for marked distal atherosclerotic disease pattern in studies of PAD is missing, and in patients with CKD, it is mainly limited to patients with ESRD.2,3,16,21,22

In this retrospective, single-center PAD patient group analysis, patency of the arterial pedal–plantar arch and occlusion of BTK arteries were assessed with respect to the coexistence of DM or CKD. The hypothesis was that loss of patency of the pedal–plantar arch is more frequent in patients with CKD compared with patients without CKD, independent of the presence of DM.

Patients and methods

Study design

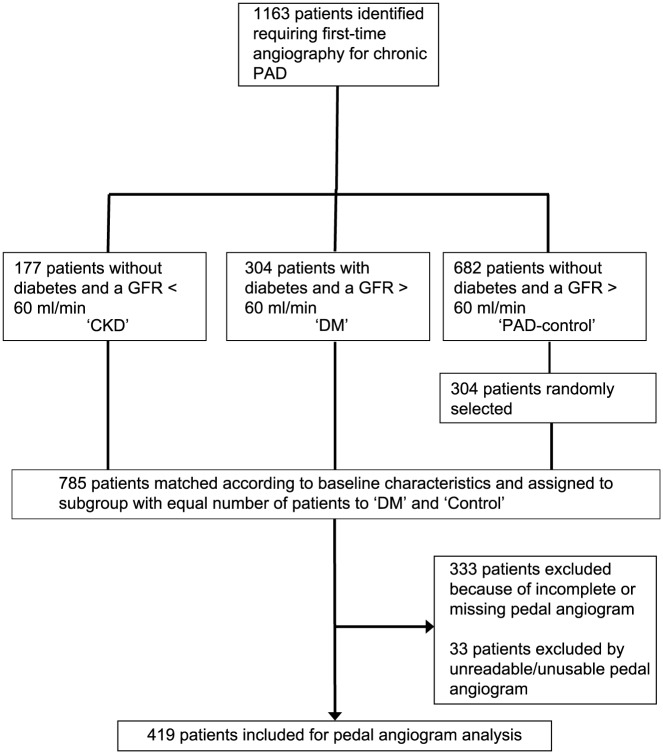

For a retrospective analysis, patients were selected from a consecutive, prospectively collected, cross-sectional database of patients undergoing digital subtraction angiography (DSA) for symptomatic PAD. The time span was from January 2010 to June 2015 for the patient’s first visit to the Swiss Cardiovascular Center, Division of Vascular Medicine at Bern University Hospital, Switzerland, a tertiary referral center responsible for peripheral vascular service in a population of about one million subjects. Noninvasive Doppler examination and duplex scan are routine first-line assessments followed by DSA if an indication for revascularization is given. It can be assumed that <5% of symptomatic patients referred were excluded from analysis because of an other-than-angiographic assessment (Figure 1). Patients with DM and CKD were consecutively selected, the PAD-control group was randomly selected to match in number of patients included. Selection of patients was regardless of their clinical status of PAD and was undertaken in a two-step procedure. In a first step, patients had to have a known and determined status of cardiovascular risk factors. In a second step, DSA had to have adequate readability of the pedal–plantar artery arch as quoted by two independent reviewers. With focus on assessing whether there is an independent influence of CKD as compared with DM on patency of the pedal–plantar arch, inclusion criterion was symptomatic PAD to prevent selection bias, for example, patients with predominant BTK disease often seen in CLI. Inclusion criteria were: patients aged > 18 years with symptomatic chronic PAD as defined according to international guidelines,23,24 ankle–brachial index < 0.9 or toe–brachial index < 0.6, undergoing DSA without previous revascularization, and readable DSA for analysis of the atherosclerotic burden of the lower limb and pedal arteries. Exclusion criteria were low-quality DSA not suitable for analysis of atherosclerotic burden, that is, unknown inflow, low-contrast filling, inadequate pedal arch documentation, nonatherosclerotic disease, acute limb ischemia, or previous revascularization. Overall, 419 patients met the inclusion criteria. Patients were stratified according to the following prespecified groups: patients without DM and without CKD (PAD-control, n = 149), patients with DM without CKD (DM, n = 183). Patients with CKD without DM (CKD, n = 87). The research protocol was approved by the institutional review board of cantonal ethic committee according to the guideline of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments. As this was a retrospective study, the need to obtain written informed consent was waived and patients’ records were anonymized before analysis.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patient enrollment.

CKD, chronic kidney disease; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; DM, diabetes mellitus; PAD, peripheral artery disease.

Angiographic scoring

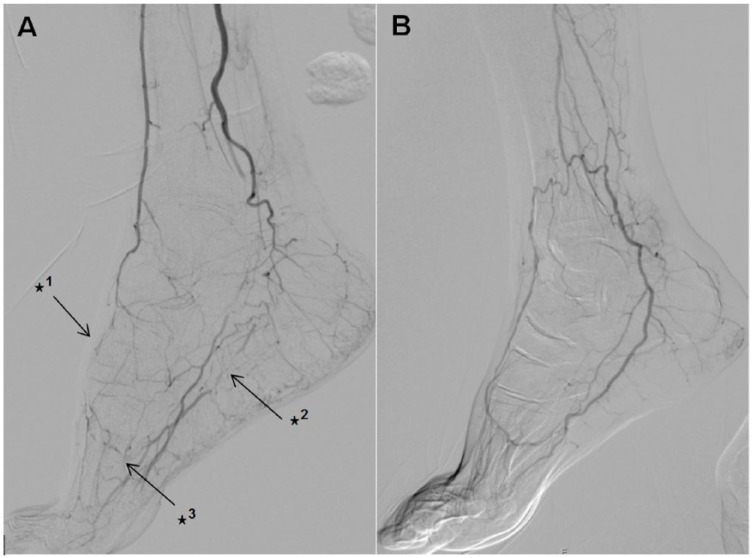

DSAs were read in a random order by two experienced readers. Both readers were blinded to clinical data, especially blinded to the groups. Patency of the pedal–plantar arch was defined according to the definition of Higashimori and colleagues17 with arterial flow through either lateral branch of the plantar–pedal artery or dorsal–pedal artery reaching the opposite artery through connection via the deep penetrating artery (Figure 2). A consensus had to be found regarding patency of the pedal–plantar loop.

Figure 2.

Interrupted dorsal–pedal artery (✶1), interrupted lateral branch of plantar–pedal artery (✶2) and interrupted pedal–plantar arch (✶3) (A); communicating dorsal–pedal artery with open lateral-branch plantar of the plantar–pedal artery with a patent pedal–plantar arch (B).

Definition of risk factors and comorbidity

Presence of DM was defined by glycosylated hemoglobin > 6.5% or if the patient was on insulin therapy or oral antidiabetics.25 CKD patients were identified by calculation of the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formula < 60 ml/min.26 CKD was classified according to severity of renal failure as moderate CKD with an eGFR of 30–59 ml/min and severe CKD with an eGFR < 29 ml/min. ESRD was defined as GFR < 15 ml/min or on dialysis.27 Arterial hypertension was defined by systolic blood pressure > 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure > 80 mmHg, or if any antihypertensive drug was consumed. Hyperlipidemia was defined by total cholesterol level > 5 mmol/l, or triglycerides > 2 mmol/l or high-density lipoprotein cholesterol < 1 mmol/l, or if any lipid-lowering drug was consumed. Patients were classified as ever-active smokers or nonsmokers, according to records.

Statistics

Descriptive analyses of sociodemographic characteristics were based on patient characteristics at the time of the performed angiogram. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are reported as mean [±standard deviation (SD)] for continuous variables and as number (percentage) for categorical variables.

Binary outcomes were analyzed using logistic regression and presented as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). p values are from Wald tests. Discrete outcomes with three or more levels were analyzed using χ2 tests. Where indicated, models were adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and smoking status. Interrater reliability was measured by kappa coefficient for nominal categorical variable (occlusion of tibial and peroneal arteries or loss of patency of pedal–plantar arch). Intrarater reliability was not evaluated. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 14.2 (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.).

Results

Baseline characteristics

Overall 419 patients fulfilling inclusion criteria and were analyzed for pedal–plantar arch patency and atherosclerotic occlusion of BTK arteries. The three groups differed statistically significant in patient number, mean age and active smoking status. Demographic data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data on 419 patients enrolled into the study.

| Total group | PAD-control | DM | CKD | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 419 | n = 149 | n = 183 | n = 87 | ||

| Age, years ± SD | 75.2 ± 10.3 | 75.2 ± 9.9 | 73.4 ± 9.8 | 79.0 ± 11.1 | <0.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 288 (69) | 103 (69) | 124 (68) | 61 (70) | 0.919 |

| Serum creatinine mean ± SD (µmol/l) | 100.6 ± 86.2 | 75.0 ± 15.5 | 75.5 ± 15.1 | 197.4 ± 152.7 | <0.001 |

| eGFR mean ± SD (ml/min) | 79.4 ± 30.5 | 90.3 ± 23.5 | 89.9 ± 24.0 | 38.6 ± 15.5 | <0.001 |

| Severe (<29 ml/min) | 23 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 23 (26%) | <0.001 |

| Moderate (30–59 ml/min) | 64 (15%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 64 (74%) | <0.001 |

| Normal (⩾60 ml/min) | 332 (79%) | 149 (100%) | 183 (100%) | 0 (0%) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.661 | ||||

| Yes | 242 (58%) | 88 (59%) | 100 (55%) | 54 (62%) | 0.474 |

| No | 115 (27%) | 42 (28%) | 51 (28%) | 22 (25%) | 0.878 |

| Unknown | 62 (15%) | 19 (13%) | 32 (17%) | 11 (13%) | 0.394 |

| Hypertension | 0.610 | ||||

| Yes | 372 (89%) | 130 (87%) | 163 (89%) | 79 (91%) | 0.696 |

| No | 41 (10%) | 17 (11%) | 16 (9%) | 8 (9%) | 0.703 |

| Unknown | 6 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 4 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0.366 |

| Active smoking | 0.011 | ||||

| Yes | 178 (42%) | 78 (52%) | 70 (38%) | 30 (34%) | 0.008 |

| No | 180 (43%) | 59 (40%) | 81 (44%) | 40 (46%) | 0.566 |

| Unknown | 61 (15%) | 12 (8%) | 32 (17%) | 17 (20%) | 0.018 |

Tests for continuous variables are ANOVAs, ✶2 tests were used for categorical variables.

CKD, chronic kidney disease; DM, diabetes; PAD-control, peripheral artery disease with neither diabetes nor chronic kidney disease; SD, standard deviation; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

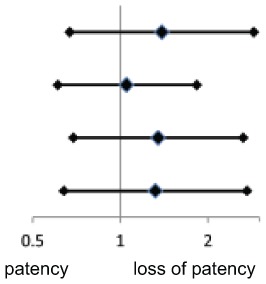

Loss of patency of the pedal–plantar loop

The adjusted ORs for loss of patency of pedal–plantar loop were higher in CKD above both PAD-control [OR 1.39 (95% CI 0.67–2.87), p = 0.37], diabetics [OR 1.32 (95% CI 0.64–2.72), p = 0.46] and both [OR 1.35 (95% CI 0.69–2.64), p = 0.38]. DM did not show a higher OR above PAD-control [OR 1.05 (0.61–1.83), p = 0.85]. However, the ORs were not statistically significant (Table 2).

Table 2.

Loss of patency of the pedal–plantar arch.

| n/n | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted* p-value | Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAD-control versus CKD | 149/87 | 1.39 (0.67–2.87) | 0.37 |

|

| PAD-control versus DM | 149/183 | 1.05 (0.61–1.83) | 0.85 | |

| PAD-control/DM versus CKD | 332/87 | 1.35 (0.69–2.64) | 0.38 | |

| DM versus CKD | 183/87 | 1.32 (0.64–2.72) | 0.46 |

Adjusted models included age, sex, hypercholesterolemia, arterial hypertension and smoking.

CKD, chronic kidney disease; DM, diabetes; PAD, peripheral artery disease; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Within the subgroup of CKD, patients’ loss of patency of the pedal loop was related to the severity of CKD. Moderate CKD (eGFR 30–59 ml/min) did not show higher ORs after controlling for age, sex, hypercholesterolemia, arterial hypertension and smoking [OR 0.93 (95% CI 0.43–2.01), p = 0.85]. Instead, patients with severe CKD (eGFR ≤29 ml/min) showed significantly increased adjusted ORs compared with patients with normal kidney function, even after adjustment for baseline factors [OR 8.24 (95% CI 0.99–68.36), p = 0.05; Table 3].

Table 3.

Association of severity of chronic kidney disease and loss of patency of pedal-plantar loop.

| OR (95% CI) | p value | Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | Adjusted* p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No CKD versus moderate CKD | 1.43 (0.78–2.60) | 0.25 | 0.93 (0.43–2.01) | 0.85 |

| No CKD versus severe CKD | 5.42 (1.25–23.52) | 0.02 | 8.24 (0.99–68.36) | 0.05 |

Adjusted models included age, sex, hypercholesterolemia, arterial hypertension and smoking.

No CKD eGFR ⩾ 60 ml/min (n = 332); moderate CKD eGFR 30–59 ml/min (n = 64); severe CKD eGFR <29 ml/min (n = 23).

CKD, chronic kidney disease; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Burden of atherosclerotic disease in below-the-knee arteries

CKD was not related to the risk of tibial or peroneal artery occlusion, whereas the risk of an occlusion of at least one BTK artery was 2.5-fold increased in patients with DM as compared with PAD-controls and CKD patients. The adjusted OR for occlusion of BTK arteries in PAD-control versus CKD was 1.09 (95% CI 0.49–2.44, p = 0.83), PAD-control versus DM was 2.41 (95% CI 1.23–4.72, p = 0.01), and CKD versus DM 2.21 (95% CI 0.93–5.22, p = 0.07), respectively.

Consistency of our interrater agreement was good to very good for rating on occlusion of tibial and peroneal arteries and moderate for rating on loss of patency of the pedal–plantar arch (Supplementary Table 1). As there was lowest interrater agreement within the subgroup of CKD, data shown refer to a consensus between two raters. For those patients without agreement with loss of patency of the pedal–plantar arch, a consensus between the two readers was found. Analysis showed comparable results if CKD was defined as plasma creatinine level > 105 µmol/l as compared with eGFR < 60 ml/min.

Discussion

Focus of this first evaluation of the pedal–plantar arch in patients with PAD was to study whether there is an independent influence of CKD and DM on patency. Severe CKD with an eGFR less than 29 ml/min seems to be an important vascular risk factor for loss of patency of the pedal-plantar arch in patients with symptomatic PAD. Moreover, analysis shows that BTK vascular disease pattern differs in patients with either DM or CKD alone. Patients with DM seem to have pronounced occlusive disease of tibial and peroneal arteries, whereas patients with severe CKD have pronounced pedal artery disease.

Studies on PAD patients providing data on patency of pedal arteries including the pedal arch are rare and include a limited number of patie-nts.2,13,16,17,28–30 Various risk factors influence the pattern of lower limb atherosclerosis in PAD patients, with DM and CKD typically associated with pronounced distal disease4,5 and vascular calcification.6 Comparative data on the disease patterns in pedal and BTK arteries with strict differentiation of patients with PAD suffering from either DM or CKD are missing.

There is growing evidence showing that even moderate renal insufficiency is associated with arterial calcification,31–33 and that coronary artery calcification, its progression and impact on a rise in cardiovascular events is associated with CKD at predialysis status.34,35 Thereby, progression rate of CAC among patients with ESRD is higher compared with diabetes patients without and also with a predialysis status.36 In accordance, loss of kidney function is also associated with an increase of calcification in PAD.22 Furthermore, it is described that a decrease in GFR level by 10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 is associated with a relative risk ratio of 1.08 for the presence of distal limb artery disease involvement with ESRD as an independent predictor for a centrifugal arterial lesion pattern (relative risk ratio 7.72, 95% CI 3.0–19.88, p < 0.0001).37 Data presented that severe CKD is associated with pedal arch occlusion are well in accordance with these findings.

Data on the atherosclerotic disease pattern in PAD with a distinction of diabetes and CKD are scarce. In a small-sized group of patients with critical limb ischemia (CKD group n = 15, DM group = 25), Diehm and colleagues have shown that patency rate of at least one pedal artery is 72% in patients with DM compared with 47% in patients with CKD and 48% for patients suffering from both CKD and DM.2 In another analysis from Brosi and colleagues, a complete occlusion of both the plantar–pedal arch and dorsal–pedal arch was found in 58% in those PAD patients with ESRD.21 Kawarada and colleagues analyzed three different types of pedal-arch patency in 85 patients with critical limb ischemia. Of those, 51% had ESRD and 78% had diabetes, showing that patency of both pedal arteries and pedal–plantar arch was present in 16%, patency of one pedal artery in 64% and loss of patency in both pedal arteries in 20% of patients.15

Analysis on patency of the pedal–plantar arch and pedal arteries is an ongoing focus for understanding poor clinical outcome after distal bypass or endovascular treatment. More than 20 years ago, it was considered that only modest success could be expected with pedal bypass grafts in patients with ESRD.14 Today, advanced endovascular techniques by transmetatarsal retrograde access of the transplantar arch can help improve clinical outcome in CLI.38,39 However, findings differ between series. Meyer and colleagues found no impact of quality of pedal arch on wound healing or survival in a cohort of 32 patients with ESRD after BTK angioplasty.18 Matsukaru and colleagues looked at perimalleolar atherosclerotic burden in PAD patients, 77% with diabetes and CKD, 60% with ESRD, that were treated with infrapopliteal (tibial or paramalleolar) arterial bypass surgery for critical limb ischemia. Those patients showing a higher atherosclerotic burden of perimalleolar arteries had a statistically significant worse outcome for amputation-free survival and overall survival rate.3 Patency of both dorsalis pedis and plantar artery results in a higher wound healing rate over patients with no or single patent pedal artery.15 Other studies found no impact of pedal arch quality on amputation-free survival but an improved outcome in wound healing for complete or incomplete pedal arch over no pedal arch.16,19 None of the studies distinguished between DM and CKD as potentially independently acting vascular risk factors. Results show an important difference between DM and CKD regarding the distal vascular disease pattern of patients with symptomatic PAD. It underlines that CKD, often coincident with diabetes, is a serious independent risk factor for pedal vascular disease, suggesting that patients with severe CKD are prone to revascularization failure and poor clinical outcome. If this hypothesis can be proven in a larger sized, adequately powered study, it might even be justified to define this as nephropathic foot syndrome.

The main limitations of our study include its retrospective design, limited generalizability due to sample size, and the possible selection bias that might contribute to results. Exclusion of patients with a pedal angiogram defined as unreadable for our analysis can be related to several factors. We assume that the lack of adherence to a standardized protocol for high-quality angiograms is likely a result of the intention to save contrast media volume, particularly as in this case the foot lesions had no clinical requirement for selective pedal angiogram, carbon dioxide contrast medium was used and fretful foot movement was apparent (Figure 1).

The study is not powered to assess the influence of patency of the pedal–plantar arch on clinical outcome, but results show an important difference in peripheral vascular disease pattern that might explain the particular poor outcome in patients with severe CKD. Moreover, no direct implication to clinical relevance can be undertaken. Duration of diabetes and CKD might have had a relevant contribution to the disease pattern as shown. However, this information was only available in a fragmentary form and a meaningful statistical computation was not feasible. That duration of diabetes and ESRD per se is an independent risk factor for vascular calcification is well described.33,40–42 Methods being used were not meant to answer the question of influence on extent of vessel wall calcification. Even using a rough semiquantitative calcification score, the study was not powered to answer whether calcification was related to patency. Moreover, adequate plain films were not always available to allow reliable, systematic post hoc analysis. Also, there is no systematic information on the comedication of patients available, in particular, long-term corticosteroid use that is associated to infragenicular vascular calcification, was unknown.43 Certain aspects on definition of the pedal arch have to be considered if data are compared with clinical outcome studies. We used the definition as previously described by Higashimori and colleagues,17 however, there is some variability in the literature.16,21,44

In conclusion, results indicate severe CKD as a vascular risk factor defining a specific subgroup of PAD patients at risk for pronounced below-the-ankle artery disease. The specific atherosclerotic disease pattern of patients with CKD and ‘nephropathic’ foot ischemia might have relevant implications with regard to contemporary endovascular revascularization strategies that needs further evaluation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

All authors have made substantial contributions to all of the following: (1) the conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; (3) final approval of the version to be submitted.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: All authors declare no competing interests with respect to this manuscript. In 2016, IB received grant support from Abbott, Cook, Terumo, Sanofi and Optimed.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Contributor Information

Axel Haine, Swiss Cardiovascular Center, Division of Angiology, Bern University Hospital, Switzerland.

Alan G. Haynes, Department of Clinical Research, University of Bern, Switzerland Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine (ISPM), University of Bern, Switzerland

Andreas Limacher, Department of Clinical Research, University of Bern, Switzerland Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine (ISPM), University of Bern, Switzerland.

Tim Sebastian, Swiss Cardiovascular Center, Division of Angiology, Bern University Hospital, Switzerland.

Wuttichai Saengprakai, Department of Surgery, Vajira Hospital, Thailand Division of Vascular Surgery, Navamindradhiraj University, Thailand.

Torsten Fuss, Swiss Cardiovascular Center, Division of Angiology, Bern University Hospital, Switzerland.

Iris Baumgartner, Clinical and Interventional Angiology, Swiss Cardiovascular Center, Inselspital, Bern University Hospital, University of Bern, 3010 Bern, Switzerland.

References

- 1. O’Hare AM, Vittinghoff E, Hsia J, et al. Renal insufficiency and the risk of lower extremity peripheral arterial disease: results from the Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study (HERS). J Am Soc Nephrol 2004; 15: 1046–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Diehm N, Rohrer S, Baumgartner I, et al. Distribution pattern of infrageniculate arterial obstructions in patients with diabetes mellitus and renal insufficiency: implications for revascularization. VASA 2008; 37: 265–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Matsukura M, Hoshina K, Shigematsu K, et al. Paramalleolar arterial Bollinger score in the era of diabetes and end-stage renal disease: usefulness for predicting operative outcome of critical limb ischemia. Circ J 2016; 80: 235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aboyans V, Criqui MH, Denenberg JO, et al. Risk factors for progression of peripheral arterial disease in large and small vessels. Circulation 2006; 113: 2623–2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Diehm N, Shang A, Silvestro A, et al. Association of cardiovascular risk factors with pattern of lower limb atherosclerosis in 2659 patients undergoing angioplasty. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2006; 31: 59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Amann K. Media calcification and intima calcification are distinct entities in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; 3: 1599–1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Coca SG, Krumholz HM, Garg AX, et al. Underrepresentation of renal disease in randomized controlled trials of cardiovascular disease. JAMA 2006; 296: 1377–1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. O’Hare AM, Bertenthal D, Shlipak MG, et al. Impact of renal insufficiency on mortality in advanced lower extremity peripheral arterial disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005; 16: 514–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tendera M, Aboyans V, Bartelink ML, et al. ; European Stroke Organisation. ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral artery diseases: document covering atherosclerotic disease of extracranial carotid and vertebral, mesenteric, renal, upper and lower extremity arteries: the task force on the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral artery diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2011; 32: 2851–2906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jude EB, Oyibo SO, Chalmers N, et al. Peripheral arterial disease in diabetic and nondiabetic patients: a comparison of severity and outcome. Diabetes Care 2001; 24: 1433–1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Faglia E, Clerici G, Clerissi J, et al. Long-term prognosis of diabetic patients with critical limb ischemia: a population-based cohort study. Diabetes Care 2009; 32: 822–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. O’Hare AM, Sidawy AN, Feinglass J, et al. Influence of renal insufficiency on limb loss and mortality after initial lower extremity surgical revascularization. J Vasc Surg 2004; 39: 709–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Karacagil S, Almgren B, Bowald S, et al. Arterial lesions of the foot vessels in diabetic and non-diabetic patients undergoing lower limb revascularisation. Eur J Vasc Surg 1989; 3: 239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnson BL, Glickman MH, Bandyk DF, et al. Failure of foot salvage in patients with end-stage renal disease after surgical revascularization. J Vasc Surg 1995; 22: 280–285; discussion 285–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kawarada O, Fujihara M, Higashimori A, et al. Predictors of adverse clinical outcomes after successful infrapopliteal intervention. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2012; 80: 861–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rashid H, Slim H, Zayed H, et al. The impact of arterial pedal arch quality and angiosome revascularization on foot tissue loss healing and infrapopliteal bypass outcome. J Vasc Surg 2013; 57: 1219–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Higashimori A, Iida O, Yamauchi Y, et al. Outcomes of one straight-line flow with and without pedal arch in patients with critical limb ischemia. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2016; 87: 129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Meyer A, Schinz K, Lang W, et al. Outcomes and influence of the pedal arch in below-the-knee angioplasty in patients with end-stage renal disease and critical limb ischemia. Ann Vasc Surg 2016; 35: 121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mochizuki Y, Hoshina K, Shigematsu K, et al. Distal bypass to a critically ischemic foot increases the skin perfusion pressure at the opposite site of the distal anastomosis. Vascular 2016; 24: 361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tuttle KR, Bakris GL, Bilous RW, et al. Diabetic kidney disease: a report from an ADA Consensus Conference. Am J Kidney Dis 2014; 64: 510–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brosi P, Baumgartner I, Silvestro A, et al. Below-the-knee angioplasty in patients with end-stage renal disease. J Endovasc Ther 2005; 12: 704–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Leskinen Y, Salenius JP, Lehtimaki T, et al. The prevalence of peripheral arterial disease and medial arterial calcification in patients with chronic renal failure: requirements for diagnostics. Am J Kidney Dis 2002; 40: 472–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Anderson JL, Halperin JL, Albert NM, et al. Management of patients with peripheral artery disease (compilation of 2005 and 2011 ACCF/AHA Guideline Recommendations): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2013; 127: 1425–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tendera M, Aboyans V, Bartelink ML, et al. ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral artery diseases: document covering atherosclerotic disease of extracranial carotid and vertebral, mesenteric, renal, upper and lower extremity arteries—the Task Force on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Artery Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2011; 32: 2851–2906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gillett MJ. International Expert Committee report on the role of the A1C assay in the diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009; 32: 1327–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, et al. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med 1999; 130: 461–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Levey AS, Eckardt KU, Tsukamoto Y, et al. Definition and classification of chronic kidney disease: a position statement from kidney disease—improving global outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int 2005; 67: 2089–2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ciavarella A, Silletti A, Mustacchio A, et al. Angiographic evaluation of the anatomic pattern of arterial obstructions in diabetic patients with critical limb ischaemia. Diabete Metab 1993; 19: 586–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Adam DJ, Beard JD, Cleveland T, et al. Bypass versus angioplasty in severe ischaemia of the leg (BASIL): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2005; 366: 1925–1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bradbury AW, Adam DJ, Bell J, et al. Bypass versus angioplasty in severe ischaemia of the leg (BASIL) trial: a description of the severity and extent of disease using the Bollinger angiogram scoring method and the TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus II classification. J Vasc Surg 2010; 51: 32S–42S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Briet M, Bozec E, Laurent S, et al. Arterial stiffness and enlargement in mild-to-moderate chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2006; 69: 350–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Porter CJ, Stavroulopoulos A, Roe SD, et al. Detection of coronary and peripheral artery calcification in patients with chronic kidney disease stages 3 and 4, with and without diabetes. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2007; 22: 3208–3213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Aragon-Sanchez J, Lazaro-Martinez JL. Factors associated with calcification in the pedal arteries in patients with diabetes and neuropathy admitted for foot disease and its clinical significance. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 2013; 12: 252–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Russo D, Palmiero G, De Blasio AP, et al. Coronary artery calcification in patients with CRF not undergoing dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2004; 44: 1024–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Russo D, Corrao S, Battaglia Y, et al. Progression of coronary artery calcification and cardiac events in patients with chronic renal disease not receiving dialysis. Kidney Int 2011; 80: 112–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mehrotra R, Budoff M, Hokanson JE, et al. Progression of coronary artery calcification in diabetics with and without chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2005; 68: 1258–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wasmuth S, Baumgartner I, Do DD, et al. Renal insufficiency is independently associated with a distal distribution pattern of symptomatic lower-limb atherosclerosis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2010; 39: 591–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Palena LM, Manzi M. Extreme below-the-knee interventions: retrograde transmetatarsal or transplantar arch access for foot salvage in challenging cases of critical limb ischemia. J Endovasc Ther 2012; 19: 805–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Palena LM, Brocco E, Manzi M. The clinical utility of below-the-ankle angioplasty using “transmetatarsal artery access” in complex cases of CLI. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2014; 83: 123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sharma A, Scammell BE, Fairbairn KJ, et al. Prevalence of calcification in the pedal arteries in diabetes complicated by foot disease. Diabetes Care 2010; 33: e66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Young MJ, Adams JE, Anderson GF, et al. Medial arterial calcification in the feet of diabetic patients and matched non-diabetic control subjects. Diabetologia 1993; 36: 615–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Duhn V, D’Orsi ET, Johnson S, et al. Breast arterial calcification: a marker of medial vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 6: 377–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Willenberg T, Diehm N, Zwahlen M, et al. Impact of long-term corticosteroid therapy on the distribution pattern of lower limb atherosclerosis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2010; 39: 441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Manzi M, Cester G, Palena LM, et al. Vascular imaging of the foot: the first step toward endovascular recanalization. Radiographics 2011; 31: 1623–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.