Abstract

Behçet disease (BD) is a chronic inflammatory multisystem disease characterized by oral and genital ulcers, uveitis, and skin lesions. Disease etiopathogenesis is still unclear. We aim to elucidate some aspects of BD pathogenesis and to identify specific gene signatures in peripheral blood cells (PBCs) of patients with active disease using novel gene expression and network analysis. 179 genes were modulated in 10 PBCs of BD patients when compared to 10 healthy donors. Among differentially expressed genes the top enriched gene function was immune response, characterized by upregulation of Th17-related genes and type I interferon- (IFN-) inducible genes. Th17 polarization was confirmed by FACS analysis. The transcriptome identified gene classes (vascular damage, blood coagulation, and inflammation) involved in the pathogenesis of the typical features of BD. Following network analysis, the resulting interactome showed 5 highly connected regions (clusters) enriched in T and B cell activation pathways and 2 clusters enriched in type I IFN, JAK/STAT, and TLR signaling pathways, all implicated in autoimmune diseases. We report here the first combined analysis of the transcriptome and interactome in PBCs of BD patients in the active stage of disease. This approach generates useful insights in disease pathogenesis and suggests an autoimmune component in the origin of BD.

1. Introduction

Behçet disease (BD) is a chronic multisystem disease mainly characterized by mucous-cutaneous lesions such as oral and genital ulcers, erythema nodosum-like lesions, and papulopustular lesions, and by uveitis. Moreover, manifestations of vascular, articular, neurologic, urogenital, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, and cardiac involvement may occur.

BD was first described by Hulusi Behçet in 1937 as a trisymptom complex represented by recurrent aphthous stomatitis, genital ulcers, and uveitis. The diagnosis of the disease is still based on clinical criteria since universally accepted pathognomonic laboratory tests are lacking. An international study group on Behcet's disease has recently revised the criteria for classification/diagnosis of BD [1].

There are sporadic cases of BD all around the world, but it is most frequently seen along the ancient Silk Route, with a prevalence of 14–20/100,000 inhabitants. According to epidemiological studies, the disease is most prevalent in countries located between 30 and 45° north latitude through the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and Far East regions such as China and Japan [2].

The interaction between a complex genetic background and both innate and adaptive immune systems leads to the clinical features of the disease. The presence of familiar cases in 10% of the patients, the particular geographic distribution and the high frequency of HLA-B51, a split antigen of HLA-B5, among a wide range of ethnic populations favours the role of genetic factors in the pathogenesis of the disease, but it remains poorly understood [3]. Non-HLA genes also contribute to the development of BD [3]. Genome-wide association studies have shown that polymorphisms in genes encoding for cytokines, activator factors, and chemokines are associated with increased BD susceptibility. Among cytokines, IL-10 polymorphisms cause a reduction of the serum level of IL-10, an inhibitory cytokine that regulates innate and adaptive immune responses; on the other hand, IL-23 receptor polymorphism, which reduces its ability to respond to IL-23 stimulation, is associated with protection from BD [3–5]. Recent data also reported associations with CCR1, STAT4, and KLRC4 encoding a chemokine receptor, a transcription factor implicated in IL-12 and IL-23 signaling and a natural killer receptor, respectively [6, 7]. Moreover, susceptibility genes implicating the innate immune response to microbial exposure have recently been identified by Immunochip analysis [8].

Increased Th1, CD4+, and CD8+ T cell, γδ + T cell, and neutrophil activities were found both in the serum and in inflamed tissues of BD patients, which suggests that innate and adaptive immunities are involved together in the pathogenesis of BD [2, 9]. Similar to other autoimmune disorders, BD shows Th1-type cytokine profiles. IL-2- and interferon- (INF-) γ-producing T cells were increased in patients with active BD, while IL-4-producing T cells were lower than in controls [10]. Recent findings have shown that Th17 may play an important role in the pathogenesis of the disease [2, 11]. This hypothesis is supported by the observation of high IL-21 and IL-17 levels in sera of patients affected by BD with neurologic involvement [12, 13]. Another study showed that Th17/Th1 ratio in peripheral blood of patients with BD was higher than those of healthy controls, whereas the Th1/Th2 and Th17/Th2 ratios were similar among the two groups. Patients with uveitis or folliculitis had higher Th17/Th1 ratio compared with patients without these manifestations [14, 15]. Further investigation is required in order to better understand the role of the immune system in BD and whether the polarization towards a Th1/Th17 pathway may play a critical role in BD pathogenesis.

In this study, we used a gene array strategy to identify transcriptional profiles of PBCs obtained from patients with active BD. Using this approach, we think we have been able to shed a new light on some aspects of the disease pathogenesis by dissecting different aspects of this complex pathology in order to better clarify the role of the immune system in BD.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Patients

We studied a cohort of 51 patients (16 males and 35 females, mean age: 37 ± 11 years) affected by BD, attending the Unit of Autoimmune Diseases at the University Hospital in Verona, Italy.

All patients fulfilled the International Criteria for Behçet Disease (ICBD): oral aphthosis, genital ulcers, and ocular lesions were each given 2 points, whereas 1 point was assigned to each of skin lesions, vascular manifestations, and neurological manifestations. A patient scoring 4 points or above was classified as having BD [16, 17].

At enrollment, none of the patients had active infections or was affected by malignancies.

A group of 10 subjects with BD was selected within the entire cohort of BD patients and utilized for the gene array study. The clinical features of the patients are reported in Table 1 that also includes a description of the BD patients selected for the gene array study.

Table 1.

Clinical features of the patients with BD included in the study.

| Patients | 51 (100%) | |

|

| ||

| Sex | Male | 16 (31%) |

| Female | 35 (68%) | |

|

| ||

| Clinical features | Aphthous stomatitis | 51 (100%) |

| Genital ulcers | 34 (66%) | |

| Erythema nodosum-like lesions | 7 (13%) | |

| Papulopustular lesion | 37 (72%) | |

| Uveitis | 5 (9%) | |

| Epididymitis | 3 (5%) | |

| Neurological symptoms | 8 (14%) | |

| Vasculitis | 6 (12%) | |

| Joints manifestations | 43 (84%) | |

| Gastrointestinal involvement | 3 (5%) | |

| Association with HLA-B51 | 32 (62%) | |

|

| ||

| Patients utilised for gene array study | 10 (100%) | |

|

| ||

| Sex | Male | 6 |

| Female | 4 | |

|

| ||

| Clinical features | Aphthous stomatitis | 10 (100%) |

| Genital ulcers | 4 (40%) | |

| Erythema nodosum-like lesions | 1 (10%) | |

| Papulopustular lesion | 8 (80%) | |

| Uveitis | 1 (10%) | |

| Epididymitis | 0 | |

| Neurological symptoms | 1 (10%) | |

| Vasculitis | 3 (30%) | |

| Joint manifestation | 8 (80%) | |

| Gastrointestinal involvement | 0 | |

| Association with HLA-B51 | 7 (70%) | |

A written informed consent was obtained from all the participants of the study. The study was approved by local Ethical Committee of the Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria of Verona, Verona, Italy. All investigations have been conducted according to the principles expressed in the Helsinki declaration.

2.2. Gene Array

Blood sample collection was prepared using PAXgene Blood RNA tubes (PreAnalytiX, Hombrechtikon, Switzerland), and total RNA was extracted by following the manufacturer's instructions. cRNA preparation, sample hybridization, and scanning were performed as recommended by the Affymetrix (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) supplied protocols and by the Cogentech Affymetrix microarray unit (Campus IFOM IEO, Milan, Italy) using Human Genome U133A 2.0 (HG-U133A 2.0) GeneChip (Affymetrix). For gene expression profile analysis, we followed the methods of Dolcino et al. [18]. Trancripts with an expression level at least 2.0 fold different in the test sample versus control sample (p ≤ 0.01) were functionally classified according to the Gene Ontology (GO) annotations and submitted to the pathway analysis using the PANTHER expression analysis tools (http://pantherdb.org/) [19]. The enrichment of all pathways associated with the differentially expressed genes compared to the distribution of genes represented on the Affymetrix HG-U133A microarray was analyzed, and p values ≤ 0.05, calculated by the binomial statistical test, were considered as significant enrichment.

2.3. Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Network Construction and Network Clustering

The search tool for the retrieval of interacting genes (STRING version 1.0; http://string-db.org/) is an online database which includes experimental as well as predicted interaction information and comprises >1100 completely sequenced organisms [20]. DEGs were directly mapped to the STRING database for acquiring significant protein-protein interaction (PPI) pairs from a range of sources, including data from experimental studies and data retrieved by text mining and homology searches [21]. PPI pairs with the combined score of ≥0.7 were retained for the construction of the PPI network.

The graph-based Markov clustering algorithm (MCL) allows the visualization of high-flow regions (clusters/modules) separated by boundaries with no flow, containing gene products that are expected to be involved in the same (or similar) biological processes [22].

In order to detect highly connected subgraphs (areas), the MCL algorithm was applied to the protein interactome graph.

Cytoscape software [22] was used to visualize all the constructed networks.

2.4. PBMCs Isolation

PBMCs were obtained from 30 healthy donors and 30 patients affected by BD through a density-gradient centrifugation on Lymphoprep (Nycomed Pharma, Oslo, NO) at 800 ×g. Cells were washed twice with PBS and counted using acridine orange (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), considering only viable cells for FACS analyses.

2.5. FACS Analysis

Cell samples were treated by following the methods of Dolcino et al. [18]. Cells were stimulated over night with Dynabeads Human T-Activator CD3/CD28 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The detection of IL-17 production was analyzed using the IL-17 Secretion Assay (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach), following the manufacturer's instruction as described in the methods of Dolcino et al. [18].

2.6. Real-Time RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from PBC using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions. PCR was performed by following the methods of Dolcino et al. [18]. Predesigned, gene-specific primers and probe sets for each gene (CCL2, CXCL2, ICAM1, and IL-8) were obtained from Assay-on-Demand Gene Expression Products (Applied Biosystems).

2.7. Detection of Soluble Mediators in Sera of BD Patients and Healthy Controls

Serum levels of TNF alpha, IL-8, CXCL1, CCL2, CCL3, and CCL20 were detected using commercially available ELISA kits (Quantikine, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions in 51 BD patients when compared to the 30 normal healthy donors.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical testing was performed using SPSS Statistics 2 software (IBM, United States). Data obtained from the analysis of the soluble mediators and from the analysis of IL-17-positive CD4+ T cells in PBMCs were analyzed using the Student's unpaired t-test.

3. Results

3.1. Gene Array Analysis

In order to identify specific gene signatures typically associated with BD, we compared the gene expression profiles of 10 PBC samples obtained from 10 individual BD patients with 10 PBC samples obtained from healthy age- and sex-matched donors.

We found that 179 modulated genes complied with the Bonferroni-corrected p value criterion (p ≤ 0.01) and the fold change criterion (FC≥2), showing robust and statistically significant variation between healthy controls and BD PBC. In particular, 160 and 19 transcripts resulted to be up- and downregulated, respectively.

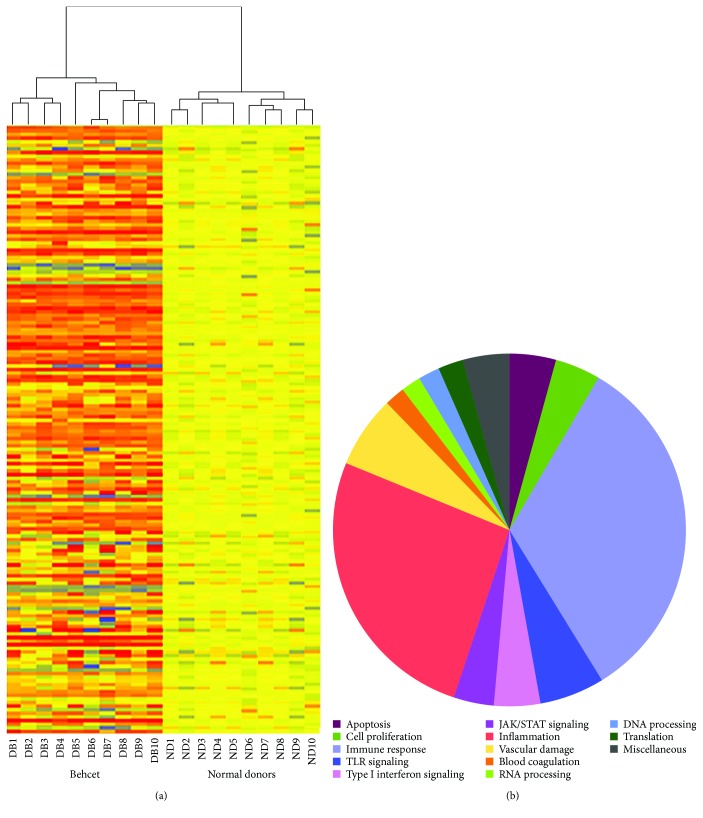

Figure 1(a) is a hierarchical cluster diagram representing the signal intensity of DEGs across samples; the heat map shows a different gene expression profile between BD patients and healthy donors that clearly separates the two sets of specimens.

Figure 1.

Modulated genes in PBCs of 10 BD patients and their functional classification. Heat map of significantly modulated genes (a). Each row represents a gene, each column shows the expression of selected genes in each individual sample. Blue-violet indicates genes that are expressed at lower levels when compared with the mean value of the control subjects, orange-red indicates genes that are expressed at higher levels when compared to the control means, and yellow indicates genes whose expression levels are similar to the control mean. Panel (b) shows the functional categorization of BD modulated genes according to GO terms. In the legend, the gene classes are listed in a clock-wise order starting at the “12 o'clock” position.

Figure 1(b) shows a functional classification of all DEGs according to the Gene Ontology (GO) terms.

The Gene Ontology analysis showed that the vast majority of the regulated transcripts can be ascribed to biological processes that may play a role in BD, including inflammation, immune response, apoptosis, blood coagulation, vascular damage, and cell proliferation. Table 2 shows a detailed selection of DEGs within the abovementioned processes. The table also includes GenBank accession numbers and fold changes. The complete list of modulated genes can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 2.

Annotated genes differentially expressed in BD PBC versus healthy controls grouped according to their function.

| Probe set ID | Gene title | Gene symbol | FC | p value | Representative public ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptive immune response | |||||

| T cell response | |||||

| 204794_at | Dual specificity phosphatase 2 | DUSP2 | 2.12 | 0.001 | NM_004418 |

| 216248_s_at | Nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 | NR4A2 | 5.54 | 0.012 | NM_006186 |

| 211861_x_at | CD28 molecule | CD28 | 2.00 | 0.014 | AF222343 |

| 203547_at | CD4 molecule | CD4 | 2.02 | 0.016 | BT019811 |

| 217394_at | T cell receptor alpha variable 13-1 | TRAV13-1 | 2.53 | 0.001 | AE000521 |

| 210439_at | Inducible T cell costimulator | ICOS | 2.26 | 0.006 | AB023135 |

| 221331_x_at | Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 | CTLA4 | 2.13 | 0.003 | NM_005214 |

| 211085_s_at | Serine/threonine kinase 4 | STK4/MST1 | 2.14 | 0.005 | Z25430 |

| 205456_at | CD3e molecule, epsilon (CD3-TCR complex) | CD3E | 2.11 | 0.004 | NM_000733 |

| 208602_x_at | CD6 molecule | CD6 | 2.47 | <0.001 | NM_006725 |

| 211302_s_at | Phosphodiesterase 4B, cAMP specific | PDE4B | 3.17 | 0.004 | L20966 |

| 218880_at | FOS-like antigen 2 | FOSL2/FRA2 | 3.17 | 0.005 | NM_005253 |

| 206360_s_at | Suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 | SOCS3 | 2.01 | 0.001 | NM_003955 |

| 212079_s_at | Lysine- (K-) specific methyltransferase 2A | KMT2A/MLL1 | 2.57 | 0.004 | NM_001197104 |

| 209722_s_at | Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade B (ovalbumin), member 9 | SERPINB9 | 2.03 | 0.001 | NM_004155 |

| B cell response | |||||

| 201694_s_at | Early growth response 1 | EGR1 | 3.86 | 0.002 | NM_001964 |

| 207655_s_at | B cell linker | BLNK | −2.10 | <0.001 | NM_013314 |

| 215925_s_at | CD72 molecule | CD72 | −2.09 | 0.015 | NM_001782 |

| 220330_s_at | SAM domain, SH3 domain, and nuclear localization signals 1 | SAMSN1 | 2.03 | 0.006 | NM_022136 |

| 204440_at | CD83 molecule | CD83 | 3.47 | NM_004233 | |

| 221239_s_at | Fc receptor-like 2 | FCRL2 | −2.36 | 0.001 | NM_030764 |

| 213810_s_at | Akirin 2 | AKIRIN2 | 3.12 | <0.001 | NM_018064 |

| T/B cell response | |||||

| 216901_s_at | IKAROS family zinc finger 1 (Ikaros) | IKZF1/IKAROS | 6.08 | <0.001 | NM_006060 |

| 221092_at | IKAROS family zinc finger 3 (Aiolos) | IKZF3/AIOLOS | 3.11 | 0.006 | NM_012481 |

| 212249_at | Phosphoinositide-3-kinase, regulatory subunit 1 (alpha) | PIK3R1 | 3.19 | <0.001 | JX133164 |

| Innate immune response | |||||

| 201278_at | Dab, mitogen-responsive phosphoprotein, homolog 2 | DAB2 | −2.17 | 0.006 | NM_032552 |

| 205033_s_at | Defensin, alpha 1 | DEFA1 | 3.80 | 0.007 | NM_004084 |

| 205468_s_at | Interferon regulatory factor 5 | IRF5 | 2.01 | <0.001 | EF064718 |

| M97935_5_at | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1, 91 kDa | STAT1 | 2.26 | 0.001 | GU211347 |

| 217199_s_at | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 2, 113 kDa | STAT2 | 2.02 | 0.002 | S81491 |

| 217502_at | Interferon-induced protein with Tetratricopeptide repeats 2 | IFIT2 | 2.00 | <0.001 | NM_001547 |

| 201211_s_at | DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 3, X-linked | DDX3X | 2.25 | <0.001 | NM_001356 |

| 211307_s_at | Fc fragment of IgA, receptor for | FCAR/CD89 | 5.04 | 0.004 | U43677 |

| 212105_s_at | DEAH (Asp-Glu-Ala-His) box helicase 9 | DHX9 | 3.82 | <0.001 | NM_001357 |

| 200613_at | Adaptor-related protein complex 2, mu 1 subunit | AP2M1 | 2.17 | <0.001 | NM_004068 |

| NK cell response | |||||

| 215339_at | Natural killer-tumor recognition sequence | NKTR | 2.15 | 0.001 | NM_005385 |

| 211242_x_at | Killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor, two domains, long cytoplasmic tail, 4 | KIR2DL4 | 2.00 | 0.004 | AF276292 |

| 216552_x_at | Killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor, two domains, short cytoplasmic tail, 4 | KIR2DS4 | 2.08 | 0.002 | NM_001281972 |

| 209722_s_at | Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade B (ovalbumin), member 9 | SERPINB9 | 2.03 | 0.001 | NM_004155 |

| Adaptive/innate immune response | |||||

| 204863_s_at | Interleukin 6 signal transducer (gp130, oncostatin M receptor) | IL6ST | 4.44 | 0.005 | AB102799 |

| 211192_s_at | CD84 molecule | CD84 | 2.32 | 0.002 | AF054818 |

| 213810_s_at | Akirin 2 | AKIRIN2 | 3.12 | 0.001 | AW007137 |

| 209722_s_at | Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade B (ovalbumin), member 9 | SERPINB9 | 2.03 | 0.001 | NM_004155 |

| 221491_x_at | Major histocompatibility complex, class II, DR beta 1 | HLA-DRB1 | 2.19 | <0.001 | U65585 |

| 213494_s_at | YY1 transcription factor | YY1 | 2.00 | 0.006 | NM_003403 |

| Toll-like receptors signaling | |||||

| 205067_at | Interleukin 1, beta | IL-1B | 6.32 | 0.001 | NM_000576 |

| 206676_at | Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 8 | CEACAM8 | 5.07 | 0.003 | M33326 |

| 204924_at | Toll-like receptor 2 | TLR2 | 2.00 | 0.015 | NM_003264 |

| 221060_s_at | Toll-like receptor 4 | TLR4 | 2.10 | 0.001 | NM_003266 |

| 211027_s_at | Inhibitor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells, kinase beta | IKBKB/IKKb | 2.33 | <0.001 | AY663108 |

| 213281_at | Jun protooncogene | JUN/AP1 | 4.51 | 0.011 | NM_002228 |

| 206035_at | V-rel reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene homolog | REL/c-REL | 2.56 | 0.005 | NM_002908 |

| 217738_at | Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase | NAMPT | 2.64 | 0.008 | NM_005746 |

| 216450_x_at | Heat shock protein 90 kDa beta (Grp94), member 1 | HSP90B1/GP96 | 3.24 | <0.001 | NM_003299 |

| 214370_at | S100 calcium binding protein A8 | S100A8 | 3.85 | <0.001 | NM_002964 |

| 211016_x_at | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 4 | HSPA4 | 2.25 | <0.001 | NM_002154 |

| 211622_s_at | ADP-ribosylation factor 3 | ARF3 | 2.12 | <0.001 | M33384 |

| Type I interferon signaling | |||||

| 205468_s_at | Interferon regulatory factor 5 | IRF5 | 2.01 | <0.001 | EF064718 |

| M97935_5_at | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1, 91 kDa | STAT1 | 2.26 | 0.001 | GU211347 |

| 217199_s_at | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 2, 113 kDa | STAT2 | 2.02 | 0.002 | S81491 |

| 216598_s_at | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 | CCL2 | 2.00 | 0.002 | S69738 |

| 210001_s_at | Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 | SOCS1 | 2.16 | 0.012 | AB005043 |

| 207433_at | Interleukin 10 | IL-10 | 2.16 | <0.001 | NM_000572 |

| 210512_s_at | Vascular endothelial growth factor A | VEGFA | 2.01 | 0.003 | AF022375 |

| 217502_at | Interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 2 | IFIT2 | 2.00 | <0.001 | NM_001547 |

| 201211_s_at | DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 3, X-linked | DDX3X | 2.25 | <0.001 | NM_001356 |

| JAK/STAT signaling | |||||

| M97935_5_at | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1, 91 kda | STAT1 | 2.26 | 0.001 | GU211347 |

| 217199_s_at | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 2, 113 kda | STAT2 | 2.02 | 0.002 | S81491 |

| 204863_s_at | Interleukin 6 signal transducer (gp130, oncostatin M receptor) | IL6ST | 4.44 | 0.005 | AB102799 |

| 207433_at | Interleukin 10 | IL-10 | 2.16 | <0.001 | NM_000572 |

| 217489_s_at | Interleukin 6 receptor | IL6R | 2.03 | 0.011 | S72848 |

| 212249_at | Phosphoinositide-3-kinase, regulatory subunit 1 (alpha) | PIK3R1 | 3.19 | <0.001 | JX133164 |

| 210001_s_at | Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 | SOCS1 | 2.16 | 0.012 | AB005043 |

| 206360_s_at | Suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 | SOCS3 | 2.01 | 0.001 | NM_003955 |

| Inflammatory response | |||||

| 207113_s_at | Tumor necrosis factor | TNF | 2.00 | 0.008 | NM_000594 |

| 211506_s_at | Interleukin 8 | IL-8 | 10.44 | 0.013 | AF043337 |

| 207433_at | Interleukin 10 | IL-10 | 2.16 | <0.001 | NM_000572 |

| 205067_at | Interleukin 1, beta | IL-1B | 6.32 | 0.001 | NM_000576 |

| 217489_s_at | Interleukin 6 receptor | IL6R | 2.03 | 0.011 | S72848 |

| 209774_x_at | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 2 | CXCL2 | 5.75 | 0.007 | M57731 |

| 201939_at | Polo-like kinase 2 | PLK2 | 6.20 | 0.012 | NM_006622 |

| 204470_at | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 | CXCL1 | 4.64 | 0.003 | NM_001511 |

| 207850_at | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 3 | CXCL3 | 3.53 | 0.015 | NM_002090 |

| 210118_s_at | Interleukin 1, alpha | IL-1A | 3.93 | 0.001 | M15329 |

| 203751_x_at | Jun D protooncogene | JUND | 3.39 | 0.008 | NM_005354 |

| 216598_s_at | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 | CCL2 | 2.00 | 0.002 | S69738 |

| 205476_at | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 20 | CCL20 | 2.23 | 0.011 | NM_004591 |

| 205114_s_at | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 3 | CCL3 | 2.21 | 0.007 | NM_002983 |

| 210001_s_at | Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 | SOCS1 | 2.16 | 0.012 | AB005043 |

| 212190_at | Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade e, member 2 | SERPINE2 | −2.14 | 0.003 | NM_006216 |

| 211919_s_at | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 4 | CXCR4 | 2.06 | 0.008 | AF348491 |

| 205099_s_at | Chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 1 | CCR1 | 2.14 | 0.002 | NM_001295 |

| 207075_at | NLR family, pyrin domain containing 3 | NLRP3 | 2.15 | 0.011 | NM_004895 |

| 203591_s_at | Colony-stimulating factor 3 receptor | CSF3R | 1.89 | 0.012 | NM_000760 |

| 215485_s_at | Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 | ICAM1 | 2.04 | 0.015 | NM_000201 |

| 209701_at | Endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1 | ERAP1 | 2.44 | <0.001 | NM_016442 |

| 216243_s_at | Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist | IL-1RN | 2.26 | 0.008 | NM_173842 |

| 202643_s_at | Tumor necrosis factor, alpha-induced protein 3 | TNFAIP3 | 2.15 | 0.012 | NM_001270508 |

| 201044_x_at | Dual specificity phosphatase 1 | DUSP1 | 4.71 | 0.013 | NM_004417 |

| 210004_at | Oxidized low-density lipoprotein (lectin-like) receptor 1 | OLR1/LOX1 | 4.13 | 0.002 | AF035776 |

| 214370_at | S100 calcium binding protein A8 | S100A8 | 3.85 | <0.001 | AW238654 |

| 213281_at | Jun protooncogene | JUN/AP1 | 4.51 | 0.011 | NM_002228 |

| 216450_x_at | Heat shock protein 90 kDa beta (Grp94), member 1 | HSP90B1/GP96 | 3.24 | <0.001 | NM_003299 |

| Vascular damage | |||||

| Blood coagulation | |||||

| 204614_at | Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade B (ovalbumin), member 2 | SERPINB2 | 3.96 | 0.013 | NM_002575 |

| 202833_s_at | Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade A, member 1 | SERPINA1 | 2.25 | <0.001 | NM_000295 |

| 207808_s_at | Protein S alpha | PROS1 | −2.16 | 0.002 | NM_000313 |

| 201110_s_at | Thrombospondin 1 | THBS1 | 5.08 | 0.001 | NM_003246 |

| 204713_s_at | Coagulation factor V (proaccelerin, labile factor) | F5 | 2.53 | 0.001 | NM_000130 |

| 203294_s_at | Lectin, mannose binding, 1 | LMAN1 | 2.50 | <0.001 | U09716 |

| 213258_at | Tissue factor pathway inhibitor (lipoprotein-associated coagulation inhibitor) | TFPI | −2.53 | 0.001 | BF511231 |

| 203650_at | Protein C receptor, endothelial | PROCR | −2.67 | 0.001 | NM_006404 |

| Angiogenesis | |||||

| 211924_s_at | Plasminogen activator, urokinase receptor | PLAUR/UPAR | 3.42 | 0.007 | NM_002659 |

| 207329_at | Matrix metallopeptidase 8 (neutrophil collagenase) | MMP8 | 2.42 | 0.012 | NM_002424 |

| 210512_s_at | Vascular endothelial growth factor A | VEGFA | 2.01 | 0.003 | AF022375 |

| 209959_at | Nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 3 | NR4A3/NOR1 | 5.69 | <0.001 | U12767 |

| 208751_at | N-Ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein, alpha | NAPA | 2.56 | 0.001 | XM_011527436 |

| Vasculitis | |||||

| 203887_s_at | Thrombomodulin | THBD | 2.00 | 0.015 | NM_000361 |

| 206157_at | Pentraxin 3, long | PTX3 | 2.22 | 0.001 | NM_002852 |

| 218880_at | FOS-like antigen 2 | FOSL2/FRA2 | 3.17 | 0.005 | NM_005253 |

| Apoptosis | |||||

| M97935_5_at | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1, 91 kDa | STAT1 | 2.26 | 0.001 | GU211347 |

| 200796_s_at | Myeloid cell leukemia sequence 1 (BCL2-related) | MCL1 | 8.02 | <0.001 | AF118124 |

| 200664_s_at | DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily B, member 1 | DNAJB1/HSP40 | 2.20 | 0.010 | NM_006145 |

| 208536_s_at | BCL2-like 11 (apoptosis facilitator) | BCL2L11 | 2.38 | 0.001 | NM_006538 |

| 213606_s_at | Rho GDP dissociation inhibitor (GDI) alpha | ARHGDIA | 2.30 | <0.001 | NM_001185077 |

| 219228_at | Zinc finger protein 331 | ZNF331/RITA | 2.50 | 0.004 | NM_018555 |

| 209722_s_at | Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade b (ovalbumin), member 9 | SERPINB9 | 2.03 | 0.001 | NM_004155 |

| 201631_s_at | Immediate early response 3 | IER3 | 2.85 | 0.001 | NM_003897 |

| 201367_s_at | ZFP36 ring finger protein-like 2 | ZFP36L2 | 9.07 | <0.001 | NM_006887 |

| Cell proliferation | |||||

| 201235_s_at | BTG family, member 2 | BTG2 | 4.53 | <0.001 | U72649 |

| 205767_at | Epiregulin | EREG | 3.51 | 0.013 | NM_001432 |

| 214052_x_at | Proline-rich coiled-coil 2C | PRRC2C/XTP2 | 3.11 | <0.001 | NM_015172 |

| 208701_at | Amyloid beta (A4) precursor-like protein 2 | APLP2 | 2.64 | <0.001 | NM_001642 |

| 217494_s_at | Phosphatase and tensin homolog pseudogene 1 | PTENP1 | 3.11 | 0.001 | AF040103 |

Bold characters indicate TH17-related genes.

Interestingly, regulated transcripts are distributed in gene categories that control different biological processes. However, the functional classes which show the highest enrichment in modulated genes are immune response (71/179) and inflammation (55/179).

Among genes ascribed to the immune response, twenty Th17-lymphocyte-related genes were upregulated including interleukin 6 signal transducer, IL6ST, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 20, CCL20, suppressor of cytokine signaling 3, SOCS3, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1, CXCL1, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 2, CXCL2, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 3, CXCL3, inducible T cell costimulator, ICOS, intercellular adhesion molecule 1, ICAM1, interleukin 8, IL-8, interleukin 1 beta, and IL-1B (see also Table 2). Some genes involved in B cell activity (CD83 molecule, CD72 molecule, Fc receptor-like 2, FCRL2, and SAM domain, SH3 domain and nuclear localization signals 1 (SAMSN1)) are modulated in patients' samples, indicating a concomitant activation of this lymphocyte cell subset in BD.

Several upregulated genes play a role in innate immunity and are expressed in neutrophils (i.e., defensin, alpha 1, DEFA1, Fc fragment of IgA, receptor, and FCAR), dendritic cells (i.e., Dab, mitogen-responsive phosphoprotein, and homolog 2 DAB2), and in macrophages (adaptor-related protein complex 2, mu 1 subunit, and AP2M1).

In agreement with the typical presence of a marked inflammatory response in BD, we also observed overexpression of several proinflammatory transcripts. The upregulated genes comprise IL-8, IL-1B, CXCL2, CXCL1, CXCL3, interleukin 1, alpha (IL-1A), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and oxidized low-density lipoprotein (lectin-like) receptor 1 (OLR1/LOX1).

Remarkably, in these two functional classes, we observed that a large number of genes are involved in well-known signaling networks that have been associated with autoimmune diseases.

These signal cascades include: (1) the interferon-alpha (IFN-A) pathway also named “type I interferon signature” [23], (2) the Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling network, and (3) the JAK/STAT signaling pathway.

In particular, 9 type I interferon-inducible genes (IFIG) were upregulated (Table 2), thus showing the presence of an IFN type I signature, typically present in autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), Crohn's disease, and Sjogren syndrome (SS) [24–30].

Twelve DEGs belong to the TLR signaling cascade (Table 2) which is thought to play a role in the onset of several autoimmune diseases and has been also implicated in the pathogenesis of BD [31–34].

Eight upregulated genes belong to the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, and interestingly, an increased JAK/STAT signaling has been associated with almost every autoimmune disease [35].

Moreover, activation of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway has been observed in monocytes and CD4+ T cells of patients with BD [36].

Several genes involved in apoptosis and/or in apoptosis regulation were modulated in BD samples including myeloid cell leukemia sequence 1 (BCL2-related), MCL-1, BCL2-like 11, BCL2L11, immediate early response 3, IER3 and ZFP36 ring finger protein-like 2, and ZFP36L2.

Cell proliferation was also deregulated, and we found modulation of several transcripts including BTG family, member 2, BTG2, epiregulin, EREG, proline-rich coiled-coil 2C (PRRC2), phosphatase, tensin homolog pseudogene 1 (PTENP1), and amyloid beta (A4) precursor-like protein 2 (APLP2).

Endothelial dysfunction and altered coagulation are typical features of BD vasculitis, and consistently with these aspects of the disease, several genes involved in vascular damage are modulated in BD specimens, including thrombospondin 1, THBS1; protein S alpha, PROS1; plasminogen activator, urokinase receptor, PLAU-UPAR; thrombomodulin, THBD; and vascular endothelial growth factor A, VEGFA.

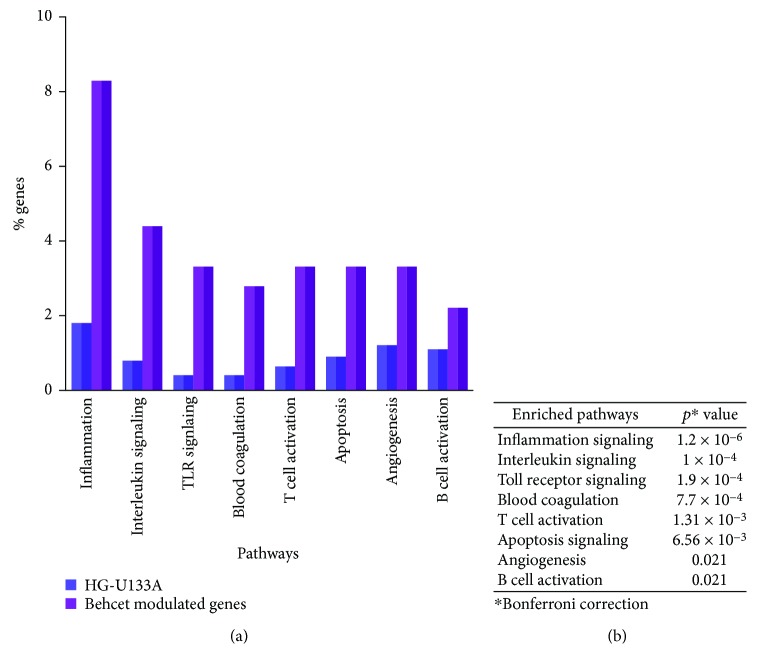

The 179 DEGs were then submitted to a pathway analysis using the PANTHER expression analysis tool and functionally annotated according to canonical pathways. Eight canonical pathways were found to be significantly overrepresented among the differentially expressed genes, and inflammation was the most enriched pathways, followed by interleukin signaling, Toll-like receptor signaling, blood coagulation, T cell activation, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and the B cell activation pathway (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Pathways enrichment of BD modulated genes. (a) Graphical representation of genes ascribed to the enriched pathways, expressed in y-axis as percentage of all genes represented on the Affymetrix Human gene chip U133A 2.0 (dark purple bars) or as the percentage of genes in the dataset of Behcet's modulated genes (light purple bars); x-axis: enriched pathways. (b) p values associated with the significantly enriched pathways. Pathways with p values < 0.05 versus the distribution of all genes on the microarray chip, after a Bonferroni correction, were considered as significantly enriched.

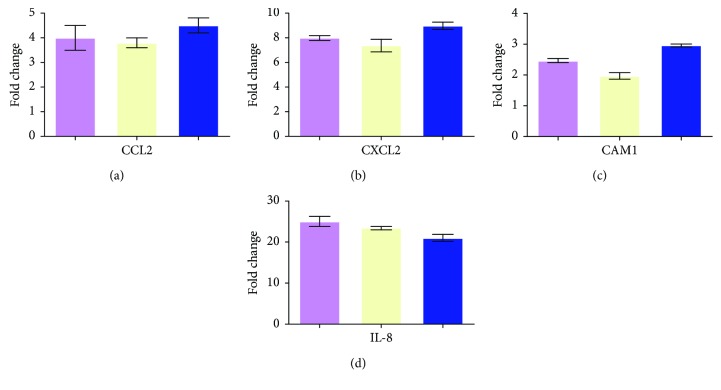

The modulation of some genes showed by gene array analysis was validated by Q-PCR (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Real-time RT-PCR of some modulated genes confirms the results of gene array analysis. Genes selected for validation were CCL2, CXCL2, ICAM1, and IL-8. All the transcripts were increased in BD samples when compared to healthy donors. Relative expression levels were calculated for each sample after normalization against the housekeeping genes 18s rRNA, beta-actin, and GAPDH. Experiments have been conducted in triplicates. Housekeeping genes: violet bar: 18s rRNA; yellow bar: beta-actin; and blue bar: GAPDH.

3.2. PPI Network Analysis

The gene expression profiling of BD PBC was then complemented by the study of functional interactions between DEGs' protein products.

To this aim, an interaction network was constructed upon the 179 DEGs, using the STRING data mining tool for retrieving well-documented connections between proteins. The obtained protein-protein interaction (PPI) network comprised 172 genes (nodes) and 2583 pairs of interactions (edges) (see Supplementary Figure 1).

When we performed a topological analysis of the PPI network using the Cytoscape software, we found that the number of interactions in which the products of the 71 “immune response genes” (see Supplementary Table 1) were involved, accounted for the vast majority (70%) of connections present in the whole network (1819/2583).

Given the high connectivity (i.e., number of connections) of the immune response gene products, we decided to perform an additional network analysis that focused on these gene products, thinking that they could be more informative.

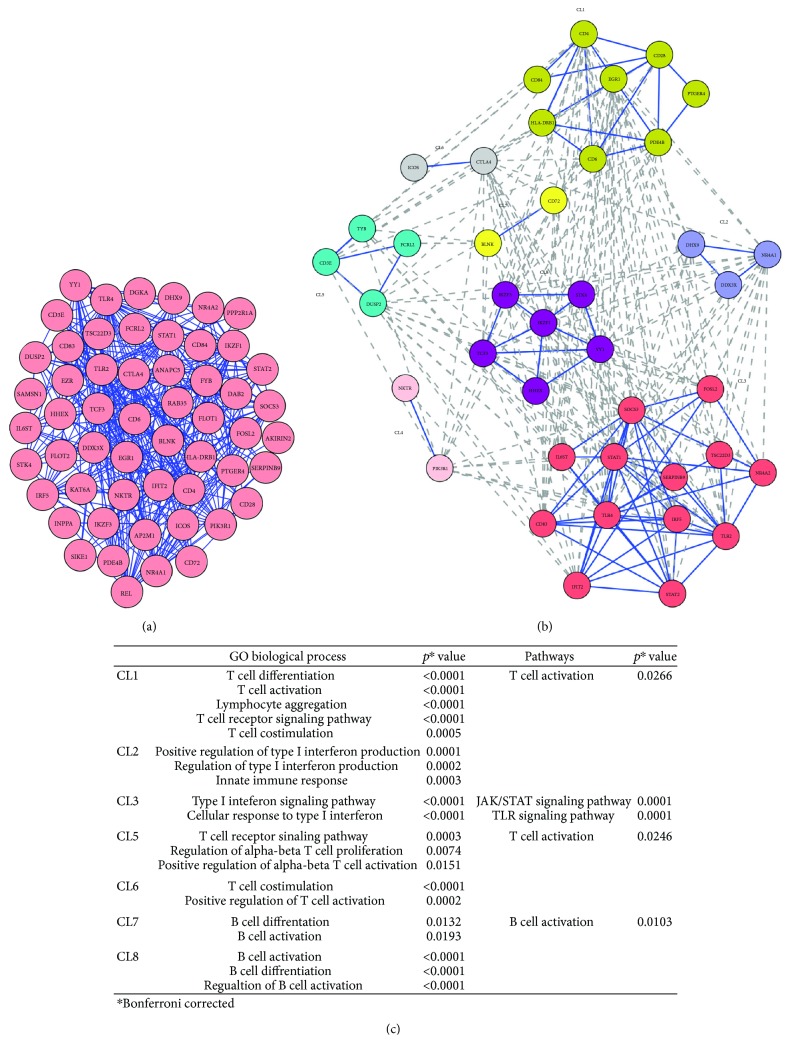

We found that 55 proteins were linked into a complex network accounting for 307 pairs of interactions. Figure 4(a) shows a graphical representation of the PPI network.

Figure 4.

Network analysis of modulated genes in BD. Panel (a): PPI network of genes involved in immune response; panel (b): clusters extracted from the PPI network; panel (c): biological processes and pathways enriched in the eight modules.

A clustering analysis was then carried out to detect clusters (modules) of proteins to which most of the interactions converged (“high flow areas”) using the MCL algorithm, and we identified eight clusters that collectively accounted for 40 nodes and 242 edges (Figure 4(b)).

We next performed a functional enrichment analysis to identify association of genes, in each cluster, with different “GO terms” and pathways.

The significantly enriched categories for each cluster are shown in Figure 4(c).

Interestingly, five out of eight clusters (CL1, CL5, CL6, CL7, and CL8) were representative of the adaptive immune response.

In particular, three clusters (CL1, CL5, and CL6) showed a statistically significant enrichment in “T cell-related” gene categories and included several genes typically associated with T cell-mediated immune responses such as: CD3E, CD4, CD6, CD28, CTLA4, and DUSP2.

The most enriched GO biological processes (GO-BP) in these clusters were: “T cell differentiation” and “T cell activation” (CL1), “T cell receptor signaling pathway” (CL5), “T cell costimulation”, and “positive regulation of T cell activation” (CL6). The most enriched pathway was the “T cell activation pathway” (CL1 and CL5).

Two clusters (CL7 and CL8) included DEGs typically associated with B cell functions (i.e., CD72). These clusters were significantly enriched in the GO-BP “B cell differentiation” (CL7) and “B cell activation” (CL7, CL8). Moreover, the B cell activation pathway was the top enriched pathway in cluster 7.

Several DEGs involved in the innate immune response (i.e., HDX9, DDX3X, SOCS3, STAT1, IRF5, IFIT2, and STAT2) were present in clusters CL2 and CL3. Interestingly, they were significantly enriched in functions of “positive regulation of type I interferon production” (CL2) and “type I interferon signaling pathway” (CL3), further confirming the presence of a type I interferon signature, typically associated with several autoimmune diseases. Moreover, genes in cluster 3 were significantly involved with the JAK/STAT signaling pathway (p = 0.0001) and the TLR signaling pathway (p = 0.0001), both implicated with the development of autoimmune diseases [31, 35]. Noteworthy, seven Th17-related proteins (CD28, CD4, ICOS, CD3E, YY1, TLR4, and IL6ST) were represented in the abovementioned clusters (CL1, CL3, CL5, CL6, and CL8). Finally, no significant GO-BP or pathway was identified in cluster CL4.

3.3. Frequency of IL-17-Positive CD4+ T Cells in PBMCs from Patients with BD

We assessed by flow cytometry the intracellular expression of the IL-17 cytokine, in PBMCs from 30 BD patients and from 30 healthy control subjects. We found a higher amount of IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells among the PBMCs of patients with BD compared with healthy controls.

The mean values obtained in 30 BD PBMC were 1% ±0.12 versus 0.4% ±0.16 (p < 0.0001) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Flow cytometric analysis of CD4+ T cells releasing IL-17 in patients with BD. Panel (a) displays the mean percentage of CD4+ T cells releasing IL-17 of 30 healthy donors and 30 BD patients. PBMCs were stimulated over night with anti-CD3/CD28-coated beads. Panel (b) shows a representative experiment ((A) normal subjects (NS); (B) BD patients).

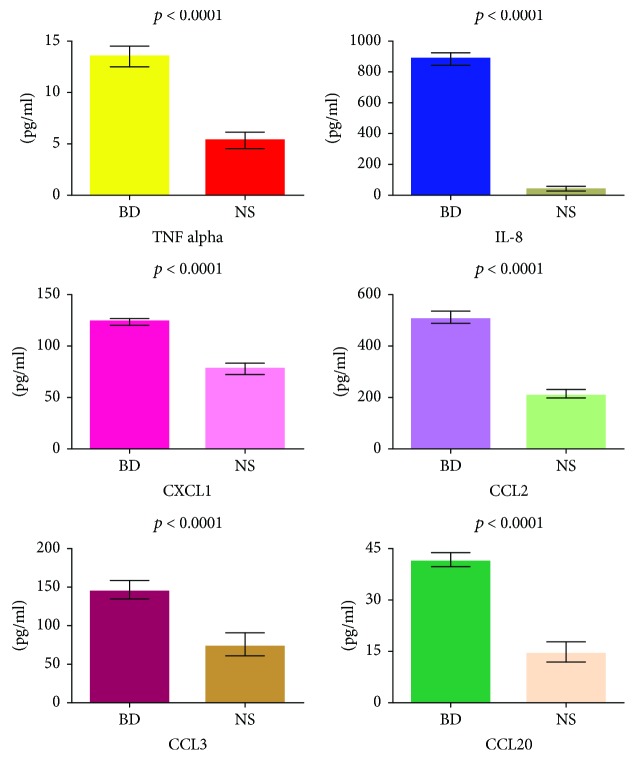

3.4. Detection of Soluble Mediators in BD Sera

The gene expression analysis was complemented by the detection of some of the corresponding soluble mediators in the sera of patients with BD. We chose to assess the levels of TNF alpha, IL-8, CXCL1, CCL2, CCL3, and CCL20. Figure 6 shows the concentration of these molecules in the sera of the 51 BD patients. All these molecules showed increased serum levels in BD patients when compared to the 30 normal healthy donors.

Figure 6.

Serum levels of selected soluble mediators in BD patients and in normal subjects. The histograms represent the mean of the results obtained in 30 normal subjects (NS) and in 51 BD patients. p values were calculated using the Student's unpaired t-test.

4. Discussion

In this paper, we report a comprehensive study of BD gene expression profiling where for the first time, a conventional global gene expression analysis was combined to a gene network analysis of functional interactions between DEGs. We believe that this integrated approach is likely to generate insights in the complex molecular pathways that control the different clinical features of BD.

The first contribution of our study is a detailed investigation of DEGs in PBCs of BD patients in the attempt to clarify some aspects of BD pathogenesis.

Indeed, the majority of DEGs analyzed is involved in biological processes closely connected to the key features of the disease.

BD is a recurrent inflammatory disease with a multisystem involvement, affecting the vasculature, mucocutaneous tissues, eyes, joints, gastrointestinal tract, and brain.

Consistently with the strong inflammatory response typical of BD, DEGs indicate upregulation of a large number of proinflammatory molecules, including TNF, IL-1, IL-8, IL-10, CXCL1, CCL2, CCL3, and ICAM1, which can be detected at increased concentration in sera or plasma of BD patients when compared to healthy controls. [37–42].

Elevated serum levels of IL-8 are detectable in the active phase of BD and indicate the presence of vascular involvement [37], whereas high serum levels of CXCL1 correlate with BD disease activity [39]. Since flares of disease are characterized by neutrophil infiltration around blood vessels following increased chemotaxis of neutrophils [43], it is not surprising to observe upregulation of CSF3R/GCSFR, which controls neutrophil functions.

Consistently with the gene array data, serum levels of the proinflammatory mediators TNF alpha, IL-8, CXCL1, CCL2, CCL3, and CCL20 were significantly higher in our cohort of 51 BD patients when compared to healthy subjects.

The main histopathological finding in BD is a widespread vasculitis of blood vessels, arteries, and veins characterized by myointimal proliferation, fibrosis, and thrombus formation leading to tissue ischemia [44]. Occlusion of the vascular lumen creates a hypoxic milieu that effectively can induce new vessel formation. Angiogenesis can further stimulate inflammation since new born endothelial cells release chemoattractive mediators for leukocytes and express adhesion molecules [44]. Several DEGs play a role in angiogenesis, and the highest level of induction was observed for NOR1 (also named NR4A3), a gene expressed in developing neointima that promotes endothelial survival and proliferation, acting as a transcription factor in vascular development [45]. DEGs also showed upregulation of NAPA, known to induce VE-cadherin localization at endothelial junctions and regulate barrier function [46]. Interestingly, soluble VE-cadherins may be increased in the sera of BD patients [47]. Another upregulated transcript was the gene encoding for UPAR, expressed in several cell types including monocytes, neutrophils, activated T lymphocytes, macrophages, and endothelial cells. Indeed, high levels of the soluble form of UPAR have been detected in the plasma of BD patients [48].

Other genes, typically associated with the vasculitic process, were overexpressed in our array including THBD and PTX3. THBD can be detected at higher levels in sera of BD patients compared with healthy controls, and it is associated with the skin pathergy test, considered as a useful test for BD diagnosis. PTX3, an acute-phase reactant produced at sites of active vasculitis, is an indicator of active small vessel vasculitis [49].

Defects in blood coagulation and fibrinolysis have been described in patients with BD with or without thrombosis, and accordingly, we found downregulation of genes encoding for proteins that have an anticoagulant effect (i.e., TFPI, PROS1, and PROCR/EPCR) and upregulation of transcripts which promote the coagulation process (including THBS1, F5, and LMAN1).

Several DEGs indicate an altered apoptotic process with up- or downregulation of several apoptosis-related genes. Endothelial cell apoptosis which plays a pivotal role in vascular damage and autoantibodies which are able to induce endothelial cell apoptosis have been reported in BD [50]. In BD, an altered apoptosis has been described also in other cell subsets, that is, neutrophils and lymphocytes. Indeed, neutrophil apoptosis is reduced in the remission phase of uveitis and is restored in the active phase [51], whereas T lymphocytes are resistant to Fas-mediated apoptosis in BD with active uveitis [52]. On the contrary, an excessive expression of FasL on skin-infiltrating lymphocytes and the presence of apoptotic cells in the skin lesions have been also reported [53], suggesting that lymphocytes expressing increased levels of FasL may have a role in the development of BD skin lesions. Among genes that control cell proliferation, we observed overexpression of the gene EREG1, which plays an autocrine role in the proliferation of corneal epithelial cells [54], and APLP2 gene, involved in corneal epithelial wound healing [55]. In this regard, it is worthwhile mentioning that keratitis can be one of the ocular manifestations of BD.

Several aspects of BD are typical of an immune-mediated disease, but whether BD is an autoimmune or an autoinflammatory disease is still debated. A great number of DEGs (71/179) are involved in the immune response, and the majority of these genes can be ascribed to the adaptive immune response. In particular, DEGs indicate a T cell response with a prevailing upregulation of many TH17-related genes.

In this regard, it is worthwhile mentioning that Th17 cells have been associated with the pathogenesis of several autoimmune diseases including psoriasis, RA, and SLE [56–58]. Noteworthy, the involvement of this T cell subset in the pathogenesis of BD has been suggested, since Th17-related cytokines are considerably increased in BD and peripheral blood Th17/Th1 ratio is significantly higher in patients with active BD compared to healthy controls [11].

To further validate our data on overexpression of the Th17 pathway in our cohort of patients, we analyzed the presence of IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells and found a significantly increased percentage of these cells in PBCs of patients with BD when compared with healthy donors.

Among DEGs regulating B cell responses, we observed overexpression of SAMSN1, a transcript induced upon B cell activation [59], and EGR1, involved in the differentiation program of B cells into plasma cells, whereas the inhibitory receptor CD72 that downmodulates B cell receptor (BCR) signaling was downregulated. All together, these data indicate the activation of the B cell immune response and (auto)antibody production suggesting a possible role of these cells in BD pathogenesis.

Other genes associated with the adaptive immune response include ICOS, SOCS3, and HLA-DRB1. Interestingly, a high expression of ICOS on CD4+ T cells has been described in BD patients with active uveitis, suggesting a role in the pathogenesis of uveitis, possibly through upregulation of IFN-g, IL-17, and TNF [60].

An increased expression of SOCS3, a regulator of the JAK/STAT pathway of cytokine induction, has been observed in all patients with BD irrespective of disease activity [61], and polymorphisms of HLA-DRB1 alleles have been associated with BD [62].

In addition, it is worthwhile mentioning that DEGs of the adaptive immune response include transcripts already associated with the development of autoimmune diseases, including CTLA4, MST1, CD6, and the abovementioned SOCS3 [63–66].

We observed that several upregulated genes, including IRF5, IFIT2, DDX3X, STAT1, and STAT2 participate to type I interferon and JAK/STAT signaling pathways.

As already mentioned, type I interferon signaling is associated with autoimmune diseases including SLE, RA, Sjogren's syndrome, and Crohn's disease [24–30].

In this regard, the copresence of type I IFN signaling and Th17-related genes suggests an autoimmune component in the origin of BD, since a synergy between IFN and Th17 pathways is commonly involved in autoimmunity [24–30, 67–69].

Moreover, the JAK/STAT signaling is activated in BD [36] and this pathway has been associated with the development of systemic autoimmune diseases such as SLE and RA [70].

Our dataset indicates also the overexpression of several genes belonging to the TLR pathway. Growing body of evidence suggests the association between TLRs and autoimmunity. Indeed, the expression of TLRs in B cells is required for the synthesis of most of the SLE-associated autoantibodies [71]. Moreover, in RA, extracellular ligands can enhance the production of the proinflammatory mediators IL6 and IL-17 in human synoviocytes and in PBCs [72]. In addition, in systemic sclerosis activation of TLR4 on the surface of fibroblasts contributes to the upregulation of profibrotic chemokines [73]. Finally, stimulation of TLR2 induces the production of IL-23 and IL-17 cytokines from the PBCs of patients affected by Sjogren's syndrome [74].

TLR2 and TLR4 have been shown to be overexpressed in PBCs from patients with eye involvement [72] and in buccal mucosal biopsies and in PBCs obtained from patients with flare of the disease [32]. Noteworthy, both TLR2 and TLR4 were upregulated in our array, in accordance with the above reported data [32, 72].

Pathway analysis may help to elucidate the pathogenesis of complex or multifactorial diseases, such as BD, that are often caused by a mixture of abnormalities of correlated transcripts or biological pathways [75]. To this aim, we mapped our DEGs onto canonical pathways to identify signaling cascades which were overrepresented in our dataset.

Interestingly, pathway enrichment analysis revealed that inflammation, IL, TLR, blood coagulation, T cell activation, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and B cell activation signaling pathways were the most enriched in BD transcriptoma, further confirming their crucial role in the disease pathogenesis.

Thanks to our global analysis we have identified modulated genes involved in biological processes that could recapitulate most of the typical features of BD. Indeed, the majority of DEGs were involved in immune response and inflammation; moreover, we observed the activation of pathways (i.e., JAK/STAT and TLRs) and the presence of signatures (i.e., type I interferon and TH17 cell) typically associated with an autoimmune response, thus suggesting an autoimmune component in the origin of BD.

We carried our analysis in order to highlight key DEGs functionally collaborating in networks that could be involved in the disease onset and progression.

Indeed, in the second part of our study, instead of looking at single component of biological processes, we aim to study the interactions among the protein products of DEGs by a network analysis.

A network representation is an intriguing way to study the complex dynamic of disease-associated molecular interactions, and in this perspective, disorders can be considered in view of disturbances of molecular networks [76]. Interestingly, we observed that the protein products of genes ascribed to the immune response showed the highest degree of connectivity in the whole network of DEGs products, thus indicating a preeminent role of this gene category in driving the global gene expression profiles in BD pathogenesis. Then, we focused our attention on the PPI network specifically obtained from the immune response gene products, since it has been described that deregulation of genes, encoding for highly interactive proteins, interferes with physiological processes and that molecules involved in diseases development show a high attitude to interact with each other [77]. The clustering analysis of this sub-network helped us to further prioritize deregulated gene products that were placed in “highest connectivity areas” (clusters) of the network, where the hubs of biological process regulation are usually positioned [78].

In most of the clusters, we found an enrichment in molecular pathways of B and T cell-mediated adaptive immune response, thus suggesting a leading role of the adaptive immunity in the pathogenesis of BD. Moreover, DEGs in these classes included genes associated with the Th17 cell response.

Interestingly, we also observed that the molecules present in the few clusters enriched in innate immune response were involved in molecular signalings known to play a role in autoimmune diseases including JAK/STAT, TLRs, and type I interferon signaling.

These findings support that the disease may be sustained by an autoimmune process and are not in contrast with the hypothesis of an autoinflammatory component in the origin of BD.

The network analysis emphasizes the crucial role played by the molecular pathways emerged from our first global gene expression study in BD pathogenesis. Indeed, the molecules that participate to these signaling pathways are concentrated in areas (clusters) of the whole network that display the highest density of connection between genes, thus indicating their prominent role in the disease.

Through this analysis, we believe that we could identify pathogenically meaningful interactions that would have been hidden in the whole native dataset and that may be strongly associated with BD. Moreover, we provide evidence, at least at a level of gene expression, that BD may have an autoimmune origin.

Finally, we believe that our data can provide a deeper insight into BD pathogenesis, highlighting crucial molecular pathways including IL-17, IL-6, and JAK/STAT pathways that may be targeted by biological drugs and by novel therapeutical strategies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Antonio Puccetti, Claudio Lunardi, and Marzia Dolcino conceived and designed the experiments. Piera Filomena Fiore, Andrea Pelosi, and Giuseppe Argentino performed the experiments. Marzia Dolcino and Andrea Pelosi analyzed the data. Elisa Tinazzi, Giuseppe Patuzzo, and Francesca Moretta selected the patients and contributed reagents. Marzia Dolcino wrote the paper with inputs from Claudio Lunardi and Antonio Puccetti. Antonio Puccetti, Piera Filomena Fiore, Andrea Pelosi, Claudio Lunardi, and Marzia Dolcino contributed equally to this paper.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1: annotated genes differentially expressed in BD PBCs versus healthy controls grouped according to their function.

Supplementary Figure 1: PPI network of modulated genes in BD PBCs.

References

- 1.International Team for the Revision of the International Criteria for Behçet's Disease (ITR-ICBD), Davatchi F., Assaad-Khalil S., et al. The International Criteria for Behçet’s Disease (ICBD): a collaborative study of 27 countries on the sensitivity and specificity of the new criteria. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2014;28(3):338–347. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alpsoy E. Behçet’s disease: a comprehensive review with a focus on epidemiology, etiology and clinical features, and management of mucocutaneous lesions. The Journal of Dermatology. 2016;43(6):620–632. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.13381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morton L. T., Situnayake D., Wallace G. R. Genetics of Behçet’s disease. Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 2016;28(1):39–44. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mizuki N., Meguro A., Ota M., et al. Genome-wide association studies identify IL23R-IL12RB2 and IL10 as Behçet’s disease susceptibility loci. Nature Genetics. 2010;42(8):703–706. doi: 10.1038/ng.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Remmers E. F., Cosan F., Kirino Y., et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants in the MHC class I, IL10, and IL23R-IL12RB2 regions associated with Behçet’s disease. Nature Genetics. 2010;42(8):698–702. doi: 10.1038/ng.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fresko I. 15th International Congress on Behçet’s Disease. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 2012;30(3 Supplement 72):S118–S128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takeuchi M., Kastner D. L., Remmers E. F. The immunogenetics of Behçet’s disease: a comprehensive review. Journal of Autoimmunity. 2015;64:137–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takeuchi M., Mizuki N., Meguro A., et al. Dense genotyping of immune-related loci implicates host responses to microbial exposure in Behçet’s disease susceptibility. Nature Genetics. 2017;49(3):438–443. doi: 10.1038/ng.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Direskeneli H., Fujita H., Akdis C. A. Regulation of TH17 and regulatory T cells in patients with Behçet disease. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2011;128(3):665–666. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugi-Ikai N., Nakazawa M., Nakamura S., Ohno S., Minami M. Increased frequencies of interleukin-2- and interferon-gamma-producing T cells in patients with active Behçet’s disease. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 1998;39(6):996–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamzaoui K. Th17 cells in Behçet’s disease: a new immunoregulatory axis. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 2011;29(4 Supplement 67):S71–S76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geri G., Terrier B., Rosenzwajg M., et al. Critical role of IL-21 in modulating TH17 and regulatory T cells in Behçet disease. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2011;128(3):655–664. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Na S. Y., Park M. J., Park S., Lee E. S. Up-regulation of Th17 and related cytokines in Behçet’s disease corresponding to disease activity. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 2013;31(3 Supplement 77):S32–S40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim J., Park J. A., Lee E. Y., Lee Y. J., Song Y. W., Lee E. B. Imbalance of Th17 to Th1 cells in Behçet’s disease. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 2010;28(4 Supplement 60):S16–S19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mat M. C., Sevim A., Fresko I., Tuzun Y. Behçet’s disease as a systemic disease. Clinics in Dermatology. 2014;32(3):435–442. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yazici H., Yazici Y. Criteria for Behçet’s disease with reflections on all disease criteria. Journal of Autoimmunity. 2014;48-49:104–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davatchi F., Chams-Davatchi C., Shams H., et al. Behcet’s disease: epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis. Expert Review of Clinical Immunology. 2017;13(1):57–65. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2016.1205486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dolcino M., Ottria A., Barbieri A., et al. Gene expression profiling in peripheral blood cells and synovial membranes of patients with psoriatic arthritis. PLoS One. 2015;10(6, article e0128262) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mi H., Thomas P. Panther pathway: an ontology-based pathway database coupled with data analysis tools. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2009;563:123–140. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-175-2_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franceschini A., Szklarczyk D., Frankild S., et al. String v9.1: protein-protein interaction networks, with increased coverage and integration. Nucleic Acids Research. 2013;41(D1):D808–D815. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensen L. J., Kuhn M., Stark M., et al. STRING 8—a global view on proteins and their functional interactions in 630 organisms. Nucleic Acids Research. 2009;37(Supplement 1):D412–D416. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bader G. D., Hogue C. W. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;4(1):p. 2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ronnblom L., Eloranta M. L. The interferon signature in autoimmune diseases. Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 2013;25(2):248–253. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32835c7e32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon R. A., Grigoriev G., Lee A., Kalliolias G. D., Ivashkiv L. B. The interferon signature and STAT1 expression in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fluid macrophages are induced by tumor necrosis factor α and counter-regulated by the synovial fluid microenvironment. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2012;64(10):3119–3128. doi: 10.1002/art.34544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nzeusseu Toukap A., Galant C., Theate I., et al. Identification of distinct gene expression profiles in the synovium of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2007;56(5):1579–1588. doi: 10.1002/art.22578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thurlings R. M., Boumans M., Tekstra J., et al. Relationship between the type I interferon signature and the response to rituximab in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2010;62(12):3607–3614. doi: 10.1002/art.27702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raterman H. G., Vosslamber S., de Ridder S., et al. The interferon type I signature towards prediction of non-response to rituximab in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2012;14(2):p. R95. doi: 10.1186/ar3819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moschella F., Torelli G. F., Valentini M., et al. Cyclophosphamide induces a type I interferon-associated sterile inflammatory response signature in cancer patients’ blood cells: implications for cancer chemoimmunotherapy. Clinical Cancer Research. 2013;19(15):4249–4261. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maria N. I., Brkic Z., Waris M., et al. MxA as a clinically applicable biomarker for identifying systemic interferon type I in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2014;73(6):1052–1059. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caignard G., Lucas-Hourani M., Dhondt K. P., et al. The V protein of Tioman virus is incapable of blocking type I interferon signaling in human cells. PLoS One. 2013;8(1, article e53881) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gianchecchi E., Fierabracci A. Gene/environment interactions in the pathogenesis of autoimmunity: new insights on the role of Toll-like receptors. Autoimmunity Reviews. 2015;14(11):971–983. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seoudi N., Bergmeier L. A., Hagi-Pavli E., Bibby D., Curtis M. A., Fortune F. The role of TLR2 and 4 in Behçet’s disease pathogenesis. Innate Immunity. 2014;20(4):412–422. doi: 10.1177/1753425913498042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu X., Wang C., Ye Z., Kijlstra A., Yang P. Higher expression of Toll-like receptors 2, 3, 4, and 8 in ocular Behcet’s disease. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2013;54(9):6012–6017. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fang J., Chen L., Tang J., et al. Association between copy number variations of TLR7 and ocular Behçet’s disease in a Chinese Han population. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2015;56(3):1517–1523. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hirahara K., Schwartz D., Gadina M., Kanno Y., O'Shea J. J. Targeting cytokine signaling in autoimmunity: back to the future and beyond. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2016;43:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tulunay A., Dozmorov M. G., Ture-Ozdemir F., et al. Activation of the JAK/STAT pathway in Behcet’s disease. Genes & Immunity. 2015;16(2):p. 176. doi: 10.1038/gene.2014.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Durmazlar S. P. K., Ulkar G. B., Eskioglu F., Tatlican S., Mert A., Akgul A. Significance of serum interleukin-8 levels in patients with Behcet’s disease: high levels may indicate vascular involvement. International Journal of Dermatology. 2009;48(3):259–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.03905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turan B., Gallati H., Erdi H., Gürler A., Michel B. A., Villiger P. M. Systemic levels of the T cell regulatory cytokines IL-10 and IL-12 in Bechçet’s disease; soluble TNFR-75 as a biological marker of disease activity. The Journal of Rheumatology. 1997;24(1):128–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kato Y., Yamamoto T. Serum levels of GRO-α are elevated in association with disease activity in patients with Behçet’s disease. International Journal of Dermatology. 2012;51(3):286–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.04998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ozer H. T. E., Erken E., Gunesacar R., Kara O. Serum RANTES, MIP-1α, and MCP-1 levels in Behçet’s disease. Rheumatology International. 2005;25(6):487–488. doi: 10.1007/s00296-004-0519-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saglam K., Yilmaz I. M., Saglam A., Ulgey M., Bulucu F., Baykal Y. Levels of circulating intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in patients with Behçet’s disease. Rheumatology International. 2002;21(4):146–148. doi: 10.1007/s00296-001-0148-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Düzgün N., Ayaşlioğlu E., Tutkak H., Aydintuğ O. T. Cytokine inhibitors: soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in Behçet’s disease. Rheumatology International. 2005;25(1):1–5. doi: 10.1007/s00296-003-0400-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neves F. S., Spiller F. Possible mechanisms of neutrophil activation in Behçet’s disease. International Immunopharmacology. 2013;17(4):1206–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maruotti N., Cantatore F. P., Nico B., Vacca A., Ribatti D. Angiogenesis in vasculitides. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 2008;26(3):476–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao Y., Bruemmer D. NR4A orphan nuclear receptors: transcriptional regulators of gene expression in metabolism and vascular biology. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2010;30(8):1535–1541. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.191163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andreeva A. V., Kutuzov M. A., Vaiskunaite R., et al. Gα 12 interaction with αSNAP induces VE-cadherin localization at endothelial junctions and regulates barrier function. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(34):30376–30383. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502844200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen T., Guo Z. P., Cao N., Qin S., Li M. M., Jia R. Z. Increased serum levels of soluble vascular endothelial-cadherin in patients with systemic vasculitis. Rheumatology International. 2014;34(8):1139–1143. doi: 10.1007/s00296-014-2949-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saylam Kurtipek G., Kesli R., Tuncez Akyurek F., Akyurek F., Ataseven A., Terzi Y. Plasma-soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) levels in Behçet’s disease and correlation with disease activity. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases. 2018;21(4):866–870. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fazzini F., Peri G., Doni A., et al. PTX3 in small-vessel vasculitides: an independent indicator of disease activity produced at sites of inflammation. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2001;44(12):2841–2850. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200112)44:12<2841::AID-ART472>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Margutti P., Matarrese P., Conti F., et al. Autoantibodies to the C-terminal subunit of RLIP76 induce oxidative stress and endothelial cell apoptosis in immune-mediated vascular diseases and atherosclerosis. Blood. 2008;111(9):4559–4570. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-092825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fujimori K., Oh-i K., Takeuchi M., et al. Circulating neutrophils in Behçet disease is resistant for apoptotic cell death in the remission phase of uveitis. Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 2008;246(2):285–290. doi: 10.1007/s00417-007-0659-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang P., Chen L., Zhou H., et al. Resistance of lymphocytes to Fas-mediated apoptosis in Behçet’s disease and Vogt-Koyangi-Harada syndrome. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation. 2002;10(1):47–52. doi: 10.1076/ocii.10.1.47.10331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wakisaka S., Takeba Y., Mihara S., et al. Aberrant Fas ligand expression in lymphocytes in patients with Behçet’s disease. International Archives of Allergy and Immunology. 2002;129(2):175–180. doi: 10.1159/000065878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morita S., Shirakata Y., Shiraishi A., et al. Human corneal epithelial cell proliferation by epiregulin and its cross-induction by other EGF family members. Molecular Vision. 2007;13:2119–2128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guo J., Thinakaran G., Guo Y., Sisodia S. S., Yu F. X. A role for amyloid precursor-like protein 2 in corneal epithelial wound healing. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 1998;39(2):292–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rother N., van der Vlag J. Disturbed T cell signaling and altered Th17 and regulatory T cell subsets in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Frontiers in Immunology. 2015;6:p. 610. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lubberts E. The IL-23–IL-17 axis in inflammatory arthritis. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 2015;11(10):p. 562. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Diani M., Altomare G., Reali E. T helper cell subsets in clinical manifestations of psoriasis. Journal of Immunology Research. 2016;2016:7. doi: 10.1155/2016/7692024.7692024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.von Holleben M., Gohla A., Janssen K. P., Iritani B. M., Beer-Hammer S. Immunoinhibitory adapter protein Src homology domain 3 lymphocyte protein 2 (SLy2) regulates actin dynamics and B cell spreading. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286(15):13489–13501. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.155184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Usui Y., Takeuchi M., Yamakawa N., et al. Expression and function of inducible costimulator on peripheral blood CD4+ T cells in Behçet’s patients with uveitis: a new activity marker? Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2010;51(10):5099–5104. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hamedi M., Bergmeier L. A., Hagi-Pavli E., Vartoukian S. R., Fortune F. Differential expression of suppressor of cytokine signalling proteins in Behçet’s disease. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology. 2014;80(5):369–376. doi: 10.1111/sji.12211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shang Y. B., Zhai N., Li J. P., et al. Study on association between polymorphism of HLA-DRB1 alleles and Behçet’s disease. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2009;23(12):1419–1422. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saverino D., Simone R., Bagnasco M., Pesce G. The soluble CTLA-4 receptor and its role in autoimmune diseases: an update. Autoimmunity Highlights. 2010;1(2):73–81. doi: 10.1007/s13317-010-0011-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Salojin K. V., Hamman B. D., Chang W. C., et al. Genetic deletion of Mst1 alters T cell function and protects against autoimmunity. PLoS One. 2014;9(5, article e98151) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pinto M., Carmo A. M. CD6 as a therapeutic target in autoimmune diseases: successes and challenges. BioDrugs. 2013;27(3):191–202. doi: 10.1007/s40259-013-0027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liang Y., Xu W. D., Peng H., Pan H. F., Ye D. Q. SOCS signaling in autoimmune diseases: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. European Journal of Immunology. 2014;44(5):1265–1275. doi: 10.1002/eji.201344369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ambrosi A., Espinosa A., Wahren-Herlenius M. IL-17: a new actor in IFN-driven systemic autoimmune diseases. European Journal of Immunology. 2012;42(9):2274–2284. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Axtell R. C., de Jong B. A., Boniface K., et al. T helper type 1 and 17 cells determine efficacy of interferon-β in multiple sclerosis and experimental encephalomyelitis. Nature Medicine. 2010;16(4):406–412. doi: 10.1038/nm.2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brkic Z., Corneth O. B., van Helden-Meeuwsen C. G., et al. T-helper 17 cell cytokines and interferon type I: partners in crime in systemic lupus erythematosus? Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2014;16(2):p. R62. doi: 10.1186/ar4499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.O'Shea J. J., Plenge R. JAK and STAT signaling molecules in immunoregulation and immune-mediated disease. Immunity. 2012;36(4):542–550. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kono D. H., Baccala R., Theofilopoulos A. N. TLRs and interferons: a central paradigm in autoimmunity. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2013;25(6):720–727. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu Y., Yin H., Zhao M., Lu Q. TLR2 and TLR4 in autoimmune diseases: a comprehensive review. Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology. 2014;47(2):136–147. doi: 10.1007/s12016-013-8402-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fineschi S., Goffin L., Rezzonico R., et al. Antifibroblast antibodies in systemic sclerosis induce fibroblasts to produce profibrotic chemokines, with partial exploitation of Toll-like receptor 4. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2008;58(12):3913–3923. doi: 10.1002/art.24049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kwok S. K., Cho M. L., Her Y. M., et al. TLR2 ligation induces the production of IL-23/IL-17 via IL-6, STAT3 and NF-κB pathway in patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2012;14(2):p. R64. doi: 10.1186/ar3780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li L., Yu H., Jiang Y., et al. Genetic variations of NLR family genes in Behcet’s disease. Scientific Reports. 2016;6(1, article 20098) doi: 10.1038/srep20098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.del Sol A., Balling R., Hood L., Galas D. Diseases as network perturbations. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2010;21(4):566–571. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Barabasi A. L., Gulbahce N., Loscalzo J. Network medicine: a network-based approach to human disease. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2011;12(1):56–68. doi: 10.1038/nrg2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Polo A., Crispo A., Cerino P., et al. Environment and bladder cancer: molecular analysis by interaction networks. Oncotarget. 2017;8(39):65240–65252. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1: annotated genes differentially expressed in BD PBCs versus healthy controls grouped according to their function.

Supplementary Figure 1: PPI network of modulated genes in BD PBCs.