Key Points

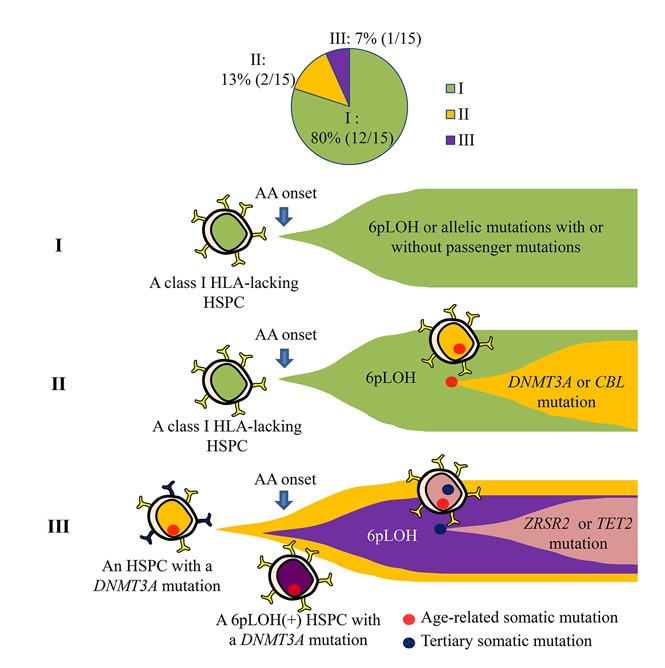

HSPCs that lack HLA class I alleles can sustain clonal hematopoiesis without driver mutations or telomere attrition in AA patients.

6pLOH may confer a survival advantage to HSPCs with age-related somatic mutations, leading to the clonal expansion of mutant HSPCs.

Abstract

Clonal hematopoiesis by hematopoietic stem progenitor cells (HSPCs) that lack an HLA class I allele (HLA− HSPCs) is common in patients with acquired aplastic anemia (AA); however, it remains unknown whether the cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) attack that allows for survival of HLA− HSPCs is directed at nonmutated HSPCs or HSPCs with somatic mutations or how escaped HLA− HSPC clones support sustained hematopoiesis. We investigated the presence of somatic mutations in HLA− granulocytes obtained from 15 AA patients in long-term remission (median, 13 years; range, 2-30 years). Targeted sequencing of HLA− granulocytes revealed somatic mutations (DNMT3A, n = 2; TET2, ZRSR2, and CBL, n = 1) in 3 elderly patients between 79 and 92 years of age, but not in 12 other patients aged 27 to 74 years (median, 51.5 years). The chronological and clonogenic analyses of the 3 cases revealed that ZRSR2 mutation in 1 case, which occurred in an HLA− HSPC with a DNMT3A mutation, was the only mutation associated with expansion of the HSPC clone. Whole-exome sequencing of the sorted HLA− granulocytes confirmed the absence of any driver mutations in 5 patients who had a particularly large loss of heterozygosity in chromosome 6p (6pLOH) clone size. Flow–fluorescence in situ hybridization analyses of sorted HLA+ and HLA− granulocytes showed no telomere attrition in HLA− granulocytes. The findings suggest that HLA− HSPC clones that escape CTL attack are essentially free from somatic mutations related to myeloid malignancies and are able to support long-term clonal hematopoiesis without developing driver mutations in AA patients unless HLA loss occurs in HSPCs with somatic mutations.

Visual Abstract

Introduction

Acquired aplastic anemia (AA) is an immune-mediated bone marrow failure triggered by T lymphocytes specific to hematopoietic stem progenitor cells (HSPCs). Approximately 70% of patients respond to immunosuppressive therapy (IST) and show the sustained restoration of hematopoiesis.1-4 However, 5% to 10% of AA patients develop myelodysplastic syndromes (MDSs) or acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) after a long latency period, and AA is therefore regarded as a preleukemic state similar to lower-risk MDSs. In keeping with this concept, various studies have revealed clonal hematopoiesis in a subset of AA patients. Studies using the lyonization of genes on the X chromosome have suggested the presence of clonal hematopoiesis in ∼30% of female patients with AA.5,6 Current studies using next-generation sequencing identified somatic mutations of various genes related to MDS, excluding PIGA, in 19% to 29% of AA patients.7,8 Founder mutations of some MDS-related genes, including ASXL1 and U2AF1, which are detected in AA patients at their presentation, may predispose them to MDS.9 However, it remains unclear how individual HSPCs with somatic mutations proliferate to build clonal hematopoiesis and affect the prognosis of AA.

Clonal hematopoiesis in AA patients may not always be associated with a preleukemic state. For example, the hematopoiesis of AA patients in remission may be supported by a limited number of healthy HSPCs that survived the immune attack by chance or by some escape mechanisms such as the absence of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored membrane proteins (GPI-APs) as a result of PIGA mutations,10,11 or the lack of class I HLAs due to a copy-number neutral loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in chromosome 6p (6pLOH).12,13 HLA-A allele–lacking leukocytes (HLA-LLs) are detectable in 34% of AA patients in remission and often account for >95% of the total granulocytes.14 Unlike patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) whose GPI-AP− HSPC clones expand and present signs of intravascular hemolysis, patients with complete clonal hematopoiesis by 6pLOH+ HSPCs do not show any abnormal laboratory or clinical findings, and are therefore being overlooked by physicians. Although the blood cell counts of patients possessing HLA-LLs who responded to IST remain almost normal for many years, the long-term support of hematopoiesis by small numbers of HSPCs may be associated with a risk of developing secondary genetic mutations in 6pLOH+ HSPCs. However, little is known about the quality of hematopoiesis supported by 6pLOH+ HSPC clones over long periods of time due to the underrecognition of 6pLOH in AA patients. It also remains unclear whether the initial cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) attack is directed at nonmutated or mutated HSPCs that present neoantigens via class I HLAs as a result of somatic mutations.

Recently, Shen et al identified the somatic mutations in GPI-AP− granulocytes in some patients with hemolytic PNH and suggested that the somatic mutations that occurred in PIGA-mutant HSPCs or that preceded PIGA mutations might have contributed to the clonal expansion of the PIGA-mutant HSPCs.15 Similar mutations may also contribute to the clonal expansion of 6pLOH+ HSPCs in some AA patients. Alternatively, 6pLOH+ HSPCs that are thought to be intact except for the lack of HLA class I alleles on the lost haplotype may have a different mutational architecture from PIGA-mutant HSPCs that lack all GPI-APs, some of which affect the survival and proliferation of HSPCs. To address these issues, we studied sorted populations of HLA-A allele–lacking (HLA−) granulocytes obtained from AA patients in long-term remission to determine the presence of somatic mutations and assessed a difference in the telomere lengths of HLA− and HLA-retaining (HLA+) granulocytes.

Materials and methods

Patients

A total of 89 patients who were diagnosed with AA at Kanazawa University Hospital or neighboring hospitals between June 2002 and January 2017 were screened for the presence of HLA-LLs; 21 patients (23.4%) were found to be positive for aberrant leukocytes. Fifteen of the 21 patients who had been in remission with an absolute neutrophil count of ≥1.5 × 109/L, a hemoglobin level of ≥10 g/dL, and a platelet count of ≥100 × 109/L for >2 years and who had a sufficient percentage of HLA− granulocytes (≥3%; supplemental Figure 1A) for DNA analyses were chosen for this study. Table 1 shows the patient characteristics: male/female (6/9); age (27-92 years; median, 55 years); severity at the time of diagnosis (very severe, n = 2; severe, n = 6; nonsevere, n = 7); disease duration (2-30 years; median, 13 years); treatment (cyclosporine [CsA] alone, n = 6; CsA plus antithymocyte globulin [ATG], n = 5; CsA plus anabolic steroids [AS], n = 2; romiplostim alone, n = 1; and AS alone, n = 1). The lineage combinations of HLA-LLs were granulocytes, monocytes, B cells, and T cells (GMBT), n = 8; granulocytes, monocytes, B cells (GMB), n = 5; and granulocytes, monocytes (GM) n = 2 (Table 2; supplemental Figure 1B). All of the patients provided their informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committees of the Kanazawa University Graduate School of Medical Science and its related facilities.

Table 1.

The clinical characteristics of the AA patients possessing HLA-A allele–lacking leukocytes

| Cases | PB count | % of GPI-AP− granulocytes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case no. | Age/sex | Original diagnosis | Disease duration, y | Treatment | Response to treatment | Leukocyte/ANC, ×109/L | Hemoglobin, g/dL | Platelet, ×109/L | Reticulocyte, ×106/L | At diagnosis | At sampling |

| 1 | 84/F | SAA | 8 | ATG + CsA | CR | 4.03/2.22 | 11.1 | 16.8 | 60 | 0.050 | NE |

| 2 | 79/F | NSAA | 12 | CsA | CR | 3.62/2.36 | 12.3 | 133 | 63 | 0.022 | 0.001 |

| 3 | 38/F | NSAA | 14 | CsA | CR | 5.47/4.44 | 11.9 | 136 | 75 | 1.050 | 0.001 |

| 4 | 92/F | SAA | 17 | CsA | CR | 3.43/1.67 | 11.8 | 98 | 38 | 0.005 | NE |

| 5 | 44/M | SAA | 11 | AS | CR | 3.92/2.88 | 13.7 | 182 | 37 | 0 | NE |

| 6 | 66/F | SAA | 16 | ATG + CsA | CR | 5.78/3.29 | 10.9 | 196 | 49 | 0.367 | NE |

| 7 | 39/F | VSAA | 15 | ATG + CsA | CR | 4.57/2.58 | 14.3 | 173 | 68 | 0 | NE |

| 8 | 74/F | NSAA | 25 | CsA | CR | 4.21/2.31 | 13.9 | 167 | NE | 0 | NE |

| 9 | 27/M | NSAA | 14 | ATG + CsA | CR | 2.44/1.30 | 14.8 | 132 | 68 | 1.140 | 0.052 |

| 10 | 42/M | SAA | 10 | CsA | CR | 3.00/1.74 | 14.3 | 159 | 63 | 0.180 | NE |

| 11 | 54/M | NSAA | 2 | CsA + AS | CR | 3.21/1.54 | 12.3 | 109 | 75 | 3.500 | NE |

| 12 | 53/F | VSAA | 3 | Romiplostim | CR | 6.30/3.81 | 14.2 | 147 | 47 | 0 | NE |

| 13 | 50/M | NSAA | 30 | CsA + AS | CR | 4.32/2.57 | 14.4 | 78 | 35 | 0 | NE |

| 14 | 58/M | SAA | 11 | ATG + CsA | CR | 3.76/1.77 | 14.4 | 208 | 59 | 0 | NE |

| 15 | 55/F | PNH | 13 | CsA | CR | 3.54/2.29 | 14 | 111 | 79 | 39.16 | 0.001 |

| →NSAA | |||||||||||

ANC, absolute neutrophil count; AS, anabolic steroids; ATG, antithymocyte globulin; CR, complete response; CsA, cyclosporine; F, female; GPI-AP−, glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored membrane proteins deficient; M, male; NE, not evaluated; NSAA, nonsevere aplastic anemia; PB, peripheral blood; PNH, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria; SAA, severe aplastic anemia; VSAA, very severe aplastic anemia.

Table 2.

The profiles and somatic mutations of HLA-A allele–lacking granulocytes

| Case no. | HLA-LLs | SNP array |

Mutated genes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lost allele | Lineage combination pattern | % in the total G population | 6pLOH frequency in HLA− granulocytes, % | CNV | Targeted sequencing, n = 15 | WES, n = 5 | Median VAF | |

| 1 | A24 | GM | 49.6 | 96 | NE | DNMT3A, ZRSR2, TET2 | NE | 0.36 |

| 2 | A31 | GMB | 99.7 | 36 (Discrepancy) | 6pLOH* | DNMT3A | NE | 0.19 |

| 3 | A2 | GMBT | 94.2 | 46† (Discrepancy) | 6pLOH* | LRCH1, PRR5L | NE | 0.11 |

| 4 | A31 | GMB | 99.0 | 99 | 6pLOH | CBL | NE | 0.33 |

| 5 | A2 | GMBT | 62.1 | 75† (Discrepancy) | 6pLOH | (−) | NE | — |

| 6 | A2 | GMBT | 5.5 | 70† (Discrepancy) | 6pLOH* | (−) | NE | — |

| 7 | A2 | GM | 6.4 | 92 | 6pLOH | (−) | NE | — |

| 8 | A2 | GMB | 9.8 | 96 | 6pLOH | (−) | NE | — |

| 9 | A24 | GMBT | 40.9 | 99 | 6pLOH | (−) | NE | — |

| 10 | A31 | GMBT | 98.6 | 33 (Discrepancy) | 6pLOH | (−) | NE | — |

| 11 | A24 | GMB | 25.1 | 92† | 6pLOH | (−) | (−) | — |

| 12 | A2 | GMBT | 97.7 | 92† | 6pLOH* | (−) | 11 genes (PPAP2B, MYSM1, FER1L5, SP5, OR2AT4, PEX5, FAM154B, SRRM2, GPR56, NLRP4, COX4I2) | 0.45 |

| 13 | A2 | GMBT | 99.8 | 99 | 6pLOH | (−)‡ | 2 genes (ZNF502, DHX35) | 0.49 |

| 14 | A2 | GMBT | 98.6 | 99 | 6pLOH | (−)‡ | 5 genes (GPT, ZNF462, CTCRTA1, OLFM4, SERPINF1) | 0.22 |

| 15 | A31 | GMB | 98.6 | 99 | 6pLOH | (−) | 3 genes (EDEM3, ATXN1L, AKAP10), 11pLOH | 0.44 |

“(Discrepancy)” indicates the presence of a discrepancy in the percentage between 6pLOH+ cells and HLA-LLs. —, not calculated; (−), not detected;

6pLOH, copy-number neutral loss of heterozygosity in chromosome 6p; CNV, copy-number variant; GM, granulocytes, monocytes; GMB, granulocytes, monocytes, B cells; GMBT, granulocytes, monocytes, B cells, and T cells; NE, not evaluated; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; VAF, variant allele frequency; WES, whole-exome sequencing.

Breakpoints of 6pLOH resided between the HLA-A and -C alleles were revealed by HLA-allelic sequencing.

6pLOH frequencies were estimated by HLA sequencing.

Previous targeted sequencing failed to reveal any mutations in 106 genes, most of which are known to be recurrently mutated in myeloid malignancies.7

Sample preparation and cell sorting

Peripheral blood (PB) samples after erythrocyte lysis were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and stained with anti-HLA-A allele-specific monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), including those specific to HLA-A2, A24, and A31, and lineage marker mAbs specific for CD33, CD3, and CD19 (supplemental Table 1). Paired fractions, including granulocytes that lacked the HLA-A allele (HLA− granulocytes) and granulocytes that retained the HLA-A allele (HLA+ granulocytes), as well as CD3+ T cells were sorted using a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS; FACSAria Fusion, BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). The sorted leukocyte populations were subjected to DNA extraction using a DNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany; supplemental Figure 1C). For 7 patients from whom sufficient numbers of HLA+ granulocytes could not be obtained due to the overwhelming percentages of HLA− granulocytes, only HLA− granulocytes were analyzed, along with T cells and buccal mucosa cells.

Targeted deep sequencing

Sixty-one genes, which were previously found to be mutated in AA, PNH, and MDS patients, were chosen for targeted capture using SeqCap EZ choice (Roche Diagnostics, Westfield, IN; supplemental Table 2).7,8,15,16 All DNA libraries of HLA− and HLA+ granulocytes and control cells (T cells or buccal mucosa cells) were prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The captured targets were subjected to the paired-end sequencing using an Illumina MiSeq system (San Diego, CA). The detail of data processing and mutation calling was described in supplemental Methods. Mutations with >20% variant allele frequencies (VAFs) were validated by Sanger sequencing whereas mutations with <20% VAFs were validated by resequencing using MiSeq.

HLA-allelic sequencing

HLA class I alleles of the sorted HLA− and HLA+ granulocyte fractions were also sequenced to determine why the HLA-A allele was missing. The allelic imbalance of HLA genes due to 6pLOH was determined by counting HLA allele–specific reads. HLA alleles were assigned using the Omixon Target software program (version 1.9.3; Omixon, Budapest, Hungary) for read alignment and genotype calling (reference sequence, IMGT/HLA Database 3.21.0). The sorted HLA− granulocytes and T cells of 2 cases were also subjected to RNA sequencing of HLA alleles and their allelic imbalances were assessed at the transcriptional level.

Whole-exome sequencing

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) was performed for the HLA− granulocytes, T cells, and buccal mucosa cells of 4 cases in which the percentage of HLA− granulocytes was particularly high (≥95%) and 1 case (case 11) involving a patient with a relatively short disease duration (2 years) and a low percentage (25.1%) of HLA− granulocytes. The captured DNA libraries were subjected to the paired-end method on a HiSequation 2500 system (Illumina). Variant analyses were performed by the same method that was used for targeted deep sequencing.

The droplet digital PCR

The percentages of 6pLOH+ granulocytes in the sorted HLA− granulocyte population were determined using a droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with a QX200 AutoDG Droplet Digital PCR System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) by comparing the copy number of each HLA allele as previously reported.17

The clonogenic assay

Colony-forming assays were performed using methylcellulose medium (MethoCult; StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. PB mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from the patients’ EDTA-containing blood using Ficoll-Hypaque (Lymphoprep; Alere Technologies, Jena, Germany), depleted of CD3+ cells using magnetic beads (phycoerythrin [PE] mouse anti-human CD3 [BD Biosciences] and anti-PE MicroBeads [Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA]), and were then incubated on a plastic plate at 37°C for 1 hour to deplete adherent cells. A total of 1.5 × 104 CD3− nonadherent cells were cultured in a petri dish containing 1 mL of Methocult for 14 days. The plucked colonies were subjected to DNA extraction for a PCR using mutation-specific primers.

The measurement of the telomere length

HLA− and HLA+ granulocytes were sorted from the patients’ PB by FACS and were subjected to the flow–fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) method (Telomere PNA kit/fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC] for flow cytometry; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) to determine the relative telomere length (RTL) according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. The RTL of the total granulocytes collected from healthy individuals and the patients were also determined using the same kit.

The human androgen receptor assay (HUMARA)

DNA extracted from female patient granulocytes and T cells was digested with HhaI and amplified using primers specific for the human androgen receptor gene. Amplified products were quantitated by an image analyzer. Skewing of the X-chromosome inactivation (XCI) pattern was assessed using the S score, which was calculated from quantities of amplified gene products from granulocyte and T-cell DNA, as described previously.3

Statistics

The differences of the telomere lengths between HLA− and HLA+ granulocytes were assessed using the paired Student t test, which was performed using the EZR software program.18

Results

Somatic mutations in HLA− granulocytes

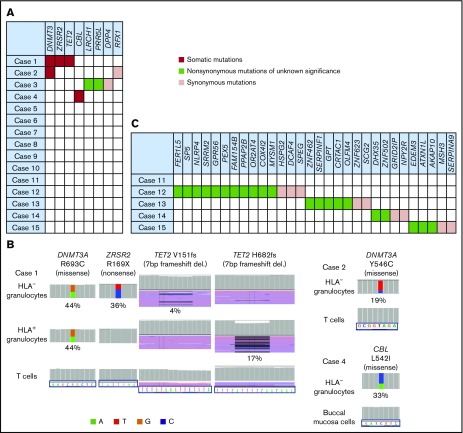

Sixty-one genes of HLA− and HLA+ granulocytes and control cells from the 15 cases were sequenced. The average coverage depth of HLA− granulocytes, HLA+ granulocytes, control cells was 493×, 534×, 391×, with more than 98.3%, 98.3%, 96.4% of the target bases covered by at least 15 reads, respectively. Somatic mutations were revealed in HLA− granulocytes from 3 of the 15 patients. The somatic mutations were those of DNMT3A (R693C and Y546C; n = 2) and TET2, ZRSR2, and CBL (n = 1); all of these mutations occurred in 3 elderly individuals (age, 79, 84, and 92 years; Figure 1A-B; supplemental Figure 3B; supplemental Table 3). With the exception of the DNMT3A (R693C) and ZRSR2 mutations of case 1, the VAFs of the 3 different mutations were far lower (4%-33%) than those of the HLA− granulocytes, which accounted for 95% of the sorted cell population in the 3 patients, suggesting that these mutations do not contribute to the expansion of the 6pLOH+ HSPCs and that the mutant HSPCs are not the targets of CTLs that allow proliferation of 6pLOH+ HSPCs.

Figure 1.

The somatic mutations detected in HLA−granulocytes. (A) A summary of targeted sequencing of the 15 cases. Somatic mutations (red), nonsynonymous mutations of unknown significance (green), and synonymous mutations (pink) are shown. (B) The somatic mutations in HLA− granulocytes and HLA+ granulocytes (left, DNMT3A, ZRSR2 and TET2 mutations in case 1; top right, a DNMT3A mutation in case 2; bottom right, a CBL mutation in case 4). HLA+ granulocytes of cases 2 and 3 were not assessable due to the paucity of the cell populations. Two different TET2 frameshift mutations were detected in case 1’s HLA− granulocytes and HLA+ granulocytes, respectively. (C) The somatic mutations detected by whole-exome sequencing (WES) in 5 cases. del., deletion.

Another patient (case 3) showed mutations in LRCH1 and PRR5L (Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 3A), both of which were included in the targeted gene analysis as our previous exome-sequencing analysis had revealed the same mutations of the 2 genes (data not shown). The other 11 patients did not show any mutations in the 61 genes, despite the fact that they had retained high percentages of their 6pLOH+ granulocytes over 2 to 30 years (Figure 1A; Table 2).

HLA− granulocyte samples from 5 patients, including 4 patients whose HLA− cell percentages were >95% of the total granulocytes were further analyzed by WES to confirm the absence of driver mutations (supplemental Figure 2). The average coverage depth of HLA− granulocytes, T cells, and buccal mucosa cells were 1089×, 1145×, 153×, with more than 97.5%, 97.9%, 63.2% of the target bases covered by at least 15 reads, respectively. The depth of WES we used was as high as that used by current studies7,19 and supported a high level of confidence in the variant calling. As shown in Figure 1C, 22 nonsynonymous and 9 synonymous mutations were detected in 4 of the 5 patients. However, no recurrent or driver mutations were detected (supplemental Table 4). The VAFs of these mutations ranged from 20.7% to 52.5% (median, 44.1%; supplemental Figure 3C).

The secondary mutations associated with the clonal expansion of a 6pLOH+ HSPC in cases 1 and 2

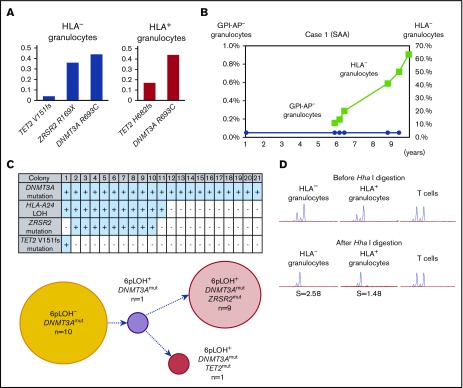

The clonal architecture and kinetic changes of HSPCs with somatic mutations in 3 patients with somatic mutations (cases 1-3) were analyzed in detail (supplemental Figure 2). The DNMT3A R693C mutation of case 1 was detected in both HLA-A24− and HLA-A24+ granulocytes and its VAF was close to 0.50, suggesting that 6pLOH occurred in an HSPC with the DNMT3A mutation (Figure 2A). The VAFs of the ZRSR2 R169X– and TET2 V151fs–mutant alleles were lower than the VAF of the DNMT3A-mutant allele in the HLA-A24− granulocytes, and the fact that the HLA-A24− granulocytes’ percentage of total granulocytes increased with time suggests that the ZRSR2 and/or TET2 mutation(s) that occurred in a DNMT3A-mutant 6pLOH+ HSPC accelerated the expansion of the mutant HSPC clone (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

The clonal expansion of HLA-A24−granulocytes associated with secondary somatic mutations in case 1. (A) The somatic mutations detected in both HLA-A24− and HLA-A24+ granulocytes and their VAFs. The numbers of nucleotide positions where mutation occurred and the resultant amino acid replacement are shown at the bottom. (B) The changes in the percentages of GPI-AP− granulocytes and HLA-A24− granulocytes during the 10-year observation period. (C) The genotypes of 21 colonies derived from PB non-T–nonadherent cells. Positivity for the amplified product of A*24:02, mutated DNMT3A, mutated ZRSR2, and mutated TET2 sequences (top panel) and their summary (bottom panel) are shown. (D) The results of HUMARA for HLA-A24− and A24+ granulocytes. Similarly skewed XCI patterns were observed in the 2 granulocyte populations in which the S scores (2.58) in HLA-A24− were higher than those in A24+ granulocyte populations (1.48), suggesting the overwhelming expansion of an HLA-A24−DNMT3AmutZRSR2mut HSPC. SAA, severe aplastic anemia.

To determine the mutual relationships between 6pLOH and the somatic mutations of DNMT3A, ZRSR2, and TET2, case 1’s PB non-T–nonadherent cells were cultured in methylcellulose medium, and individual colonies (n = 21) were examined using HLA-A*24:02 or mutation-specific primers with a PCR. All colonies showed DNMT3A mutations and only half of the colonies with ZRSR2 or TET2 mutations were 6pLOH+. The clonogenic assays confirmed the acquisition of a secondary ZRSR2-gene nonsense mutation and a TET2-gene frameshift mutation by 6pLOH+DNMT3Amut clones (Figure 2C). The predominance of single clones in both HLA-A24− and A24+ granulocyte populations was confirmed by the markedly high S score in the HUMARA (Figure 2D). The clonal architecture deduced from these results is shown in supplemental Figure 4A.

In contrast, the percentages of DNMT3A Y546C mutations in case 2 showed a slight increase over the last 4 years (Figure 3A). The patient’s granulocytes consisted of 2 different HLA-A31− populations including 36% 6pLOH+ granulocytes and 64% HLA-A31− granulocytes without either 6pLOH or A*31:01 mutations (6pLOH−A*31:01mut−; Figure 3B). Although the HLA-A31− granulocytes of case 2 had not been assessed during the first 8 years after the diagnosis, the HLA-A31− granulocyte percentage of total granulocytes remained to nearly 100% over the last 4 years (Figure 3C). Individual colony analyses (n = 4) using HLA-A*31:01 and DNMT3A mutation-specific primers showed that DNMT3A mutations were only detected in 6pLOH+ colonies (Figure 3D). The results of HUMARA suggested oligoclonality rather than monoclonality of the HLA-A31− granulocytes (Figure 3E). These results suggested that the DNMT3A mutation may have contributed to the expansion of a moderate increase in the percentage of a 6pLOH+ HSPC clone; however, the 6pLOH−A*31:01mut− HSPC was still predominant (supplemental Figure 4B).

Figure 3.

The clonal architecture of HLA-A3101−granulocytes in case 2. (A) Changes in the VAF of the DNMT3A mutation during the last 6-year study (7-12 years after the diagnosis). (B) The composition of HLA-A3101− granulocytes, as revealed by HLA-A allelic sequencing. 6pLOH−A*31:01mut− cells accounted for 64% of the total HLA-A3101− granulocytes. (C) The chronological changes in the GPI-AP− granulocytes and HLA-A3101− granulocytes. (D) The genotypes of 4 colonies derived from PB non-T–nonadherent cells. Whether individual colonies are positive or negative for the amplified product of A*31:01 and mutated DNMT3A (top panel) and their summary (bottom panel) are shown. (E) The results of HUMARA for HLA-A3101− granulocytes. The S score was as low as 1.17, and was in line with the results of HLA-A–allelic sequencing, which showed the presence of >2 HLA-A3101− HSPC clones. NSAA, nonsevere aplastic anemia.

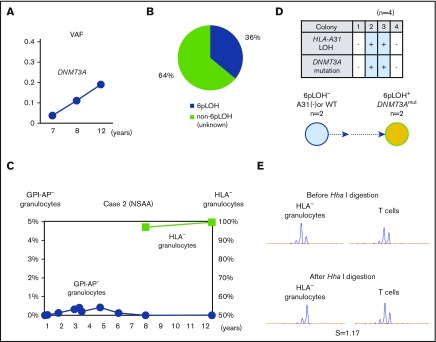

The clonal architecture of HLA-A2− granulocytes of case 3 with nonsynonymous mutations of unknown significance

The percentages of LRCH1 and PRR5L in case 3 remained stable for 10 years (Figure 4A). The patient’s granulocytes were estimated to consist of 3 different HLA-A2− populations, including 46% 6pLOH+ granulocytes, and 5% HLA-A2− granulocytes due to a nonsense mutation in the HLA-A*02:06 (A*02:06mut+), and 49% A2-lacking granulocytes due to unknown mechanisms (6pLOH−A*02:06mut−; Figure 4B). The percentage of HLA− granulocytes slightly increased from 92% to 94% over a 6-year period, whereas the percentage of GPI-AP− granulocytes gradually decreased from 2.8% to 0% (Figure 4C). A clonogenic assay using HLA-A*02:06 or mutation-specific primers revealed that both LRCH1-mutant (LRCH1mut) and PRR5L-mutant (PRR5Lmut) progenitor cells retained HLA-A*02:06, indicating that these mutations occurred in A2−6pLOH− HSPCs and that the patient’s hematopoiesis was supported by 3 HLA-A2− HSPC clones, including 6pLOH+, 6pLOH−PRR5Lmut, and 6pLOH−PRR5LmutLRCH1mut clones in addition to wild-type (WT) HSPCs (Figure 4D). The mosaicism of the patient’s hematopoiesis due to the presence of the 3 mutant HSPC clones and WT HSPCs, was in agreement with the mild skewing of the inactivation pattern of HUMARA (Figure 4E). Taken together, immune pressure on bone marrow HSPCs was thought to have given a survival advantage to HLA-A2− HSPCs, leading to the occurrence of the PRR5L mutation in a daughter clone of the A2−6pLOH− HSPCs followed by the occurrence of the LRCH1 mutation in a daughter clone of A2−6pLOH−PRR5Lmut HSPCs (supplemental Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

The clonal architecture of the HLA-A2−granulocytes in case 3. (A) The changes in the VAF of LRCH1- and PRR5L-mutant clones during the 12-year observation period. (B) The clonal composition of HLA− granulocytes, as revealed by HLA-A–allelic sequencing. An HLA-A*02:06-mutant clone (nonsense mutation) accounted for 5% of HLA-A2− granulocytes. (C) The chronological changes in the percentage of GPI-AP− granulocytes and HLA-A2− granulocytes. (D) The genotypes of 27 colonies derived from PB non-T–nonadherent cells. Whether individual colonies are positive or negative for the amplified product of A*02:06, mutated LRCH1, and mutated PRR5L sequences (top panel) and the summary of the colony genotypes (bottom panel) are shown. (E) The results of HUMARA. The relatively low S score (0.56), of the HLA− granulocytes was compatible with the results of HLA-A*02:06 sequencing, which showed triclonality.

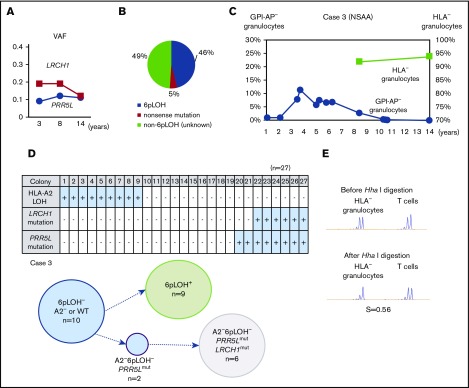

Multiple passenger mutations revealed by WES in 2 patients with large 6pLOH+ clones

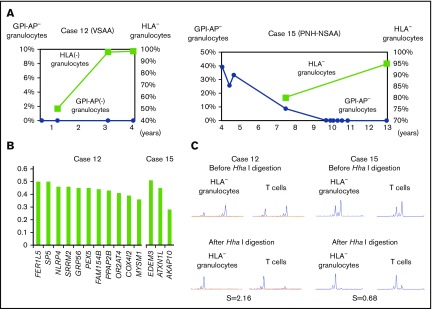

WES revealed that the VAFs of several mutated genes were very high in 2 patients (cases 12 and 15). Case 12 failed to receive ATG therapy due to cerebral hemorrhage and her refractoriness to platelet transfusions, but achieved remission after monotherapy with romiplostim (supplemental Discussion). The patient’s HLA-A2− granulocyte percentage increased from 50.1% to 98.4% during the therapy (Figure 5A left), and HLA-A2− granulocytes obtained 3 years after the start of romiplostim therapy showed various gene mutations that were thought to have occurred before or soon after the acquisition of 6pLOH (Figure 5B left), based on the high VAFs of each mutant allele and clonal predominance, as demonstrated by HUMARA (Figure 5C left). Case 15 showed spontaneous regression of PNH and an increase in the percentage of HLA− granulocytes during 5 years of observation without therapy (Figure 5A right). Three gene mutations were thought to have occurred simultaneously in a 6pLOH+ HSPC clone, given their high VAFs (Figure 5B right) and clonal predominance, as revealed by HUMARA (Figure 5C right). The deduced clonal architectures of cases 12 and 15 are shown in supplemental Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Clonal hematopoiesis revealed by WES in 2 cases. (A) The chronological changes of HLA− granulocytes and GPI-AP− granulocytes in case 12 (left) and case 15 (right). In case 15, which involved a patient who had been diagnosed with hemolytic PNH, the spontaneous resolution of PNH was observed; however, clonal hematopoiesis was subsequently developed by an HLA-A31− HSPC. (B) The VAFs of each gene mutation detected in case 12 (left) and case 15 (right). (C) The results of HUMARA for HLA-A2− granulocytes of case 12 (left) and HLA-A31− granulocytes of case 15 (right). Extremely high (2.16 in case 12) and low (0.68 in case 15) S scores indicate the presence of apparent clonal hematopoiesis in both patients. VSAA, very severe aplastic anemia.

HLA allelic sequencing

Deep sequencing of HLA alleles revealed that, in 4 cases, the breakpoints of 6pLOH resided between the HLA-A and -C alleles of the affected haplotype, resulting in the loss of HLA-A2 (cases 3, 6 and 12) or HLA-A31 allele (case 2). Moreover, a nonsense mutation of HLA-A*02:06 was detected in case 3, strongly suggesting that autoantigens were presented by HLA-A0206. On the other hand, HLA− granulocytes without either 6pLOH or allelic mutations were also seen in 5 cases (HLA-A2, n = 3; HLA-A31, n = 2). In cases 2 and 3, RNA sequencing of the sorted A31− and A2− granulocyte populations, which comprised 64% 6pLOH− and 49% 6pLOH−A*02:06mut− cells, showed markedly lower messenger RNA levels of A*31:01 and A*02:06 than those of contralateral alleles (A*02:06 and A*01:01), suggesting an underlying epigenetic mechanism that resulted in the lack of HLA-A allele expression.20,21

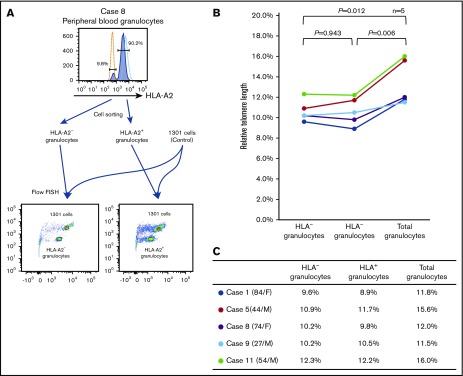

The telomere length of HLA− and HLA+ granulocytes

In 5 cases, the numbers of HLA− and HLA− granulocytes were sufficient to allow for the measurement of the telomere length using a flow-FISH method. Although the telomere length of FACS-sorted granulocytes tended to be shorter than that of unsorted total granulocytes, likely due to cell damage caused by mechanical stress (supplemental Figure 6B), a comparison of the telomere lengths of the 2 cell populations was feasible. As shown in Figure 6A-B, the telomere length of HLA− granulocytes was comparable to that of HLA+ granulocytes in all 5 patients. The RTLs (percentages) of the 5 patients are summarized in Figure 6C.

Figure 6.

The telomere length of HLA−and HLA+granulocytes. (A) A representative result of flow-FISH for case 8 is shown. (B-C) The RTLs of HLA− granulocytes, HLA+ granulocytes, and total granulocytes are shown.

Discussion

This study analyzed HLA− granulocytes derived from the 6pLOH+ HSPCs of 15 AA patients who were in remission and in whom stable hematopoiesis had been sustained for >2 years (median, 13 years). Targeted sequencing, which was performed to investigate the presence of somatic mutations, revealed that, with the exception of 1 case, no such driver mutations were involved in the sustained hematopoiesis by 6pLOH+ HSPC clones. In the 1 exception (case 1), 6pLOH was thought to have occurred in an HSPC with a DNMT3A mutation. WES of HLA− granulocytes from 4 patients whose granulocytes consisted almost solely of 6pLOH+ cells revealed several somatic mutations in all 4 patients; however, none of the gene mutations were known to be driver genes. Our previous studies using whole blood DNA and WES also failed to detect significant gene mutations in cases 2, 3, and 9 (T.I., T.Y., S.O., and S.N., unpublished observation).7 A current study by Babushok et al revealed MDS-related gene mutations and clonal evolution in AA patients possessing high-risk HLA alleles, the expression of which was often lacked as a result of 6pLOH or allelic mutations.22 However, in agreement with our study, the study revealed MDS-related mutations in only 1 of 7 6pLOH+ patients. These findings suggest that 6pLOH+ HSPCs that escape CTL attacks at the development of AA do not require driver gene mutations to sustain hematopoiesis in the majority of AA patients who remain in remission for long periods of time.

The somatic mutations that have been implicated in the development of MDS, including DNMT3A, TET2, ZRSR2, and CBL, were detected in only 3 patients, who were all >65 years of age at the onset of AA. These gene mutations are reported to be detectable in the leukocytes of healthy individuals of >55 years of age with VAFs of <0.20.23 According to the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) database (http://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic), 2 DNMT3A (R693C and Y546C) and ZRSR2 mutations were previously reported in malignant hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, whereas the other 2 mutations in TET2 and CBL were novel (supplemental Table 3). HSPCs with such age-related somatic mutations in elderly individuals may undergo 6pLOH and escape the CTL attack to contribute to hematopoiesis in AA patients. This secondary occurrence of 6pLOH in an HSPC that had been affected by an age-related somatic mutation was indeed observed in case 1, a 6pLOH+ HSPC that showed clonal expansion. Although the presence of DNMT3A mutations is associated with a high risk of developing MDS or AML in AA patients,7,19,24,25 how DNMT3A mutations make HSPCs prone to malignancy remains unknown. The findings of case 1 suggest that in elderly AA patients possessing HSPCs with DNMT3A mutations, the mutant HSPCs can undergo 6pLOH and may acquire a survival advantage over normal HSPCs at the onset of AA. The resultant proliferation of 6pLOH+DNMT3Amut HSPCs may have made them more susceptible to tertiary mutations such as those in TET2 and ZRSR2, leading to the extensive proliferation of the mutant HSPCs.26-31

Similar to 6pLOH+ HSPCs, the expansion of PIGA-mutant HSPCs is considered to be selected as a result of an immune attack against HSPCs, and constitute clonal hematopoiesis in PNH patients.10 It has been believed that secondary hits in PIGA-mutant HSPCs are required for patients to develop PNH. However, a recent study by Shen et al revealed secondary or ancestral somatic mutations in GPI-AP− granulocytes of only half of their PNH patients. Most of the secondary mutations to PIGA mutations that were found in 10% of the patients were not of driver genes.11 These findings are in agreement with the results of this study. Clonal hematopoiesis by mutant HSPCs that are selected as a result of the immune attack against HSPCs may therefore be supported by their intrinsic high proliferation and differentiation abilities.32

We originally hypothesized that telomere attrition might occur in HLA− granulocytes as a result of the extensive proliferation of a few HLA− HSPC clones. A previous study of PNH patients showed that the telomere length of PNH-type granulocytes was significantly shorter than that of normal granulocytes.33,34 In the current study, however, no difference was observed in the telomere length between sorted HLA− and HLA+ granulocyte populations. Some other studies of PNH patients also failed to reveal telomere attrition in sorted GPI-AP− granulocytes.35 Robertson et al demonstrated that there was no difference in the telomere length of granulocytes between elderly individuals with XCI and those without XCI.36 They hypothesized that the HSPCs responsible for clonal hematopoiesis in elderly individuals might maintain their telomere length through their adequate telomerase activity. The HLA− HSPC clones of AA patients in remission may also regulate their telomere length through their appropriate telomerase activity, which would help them to maintain their genetic stability. The findings also suggest that the extensive proliferation of healthy HSPCs may not make them susceptible to secondary MDS in AA patients.

In conclusion, HLA− HSPCs caused by 6pLOH or other mechanisms support long-term hematopoiesis without the development of driver mutations in the majority of AA patients; as such, clonal hematopoiesis by 6pLOH+ HSPCs may not portend a poor prognosis. The absence of somatic mutations in HLA− granulocytes in the majority of AA patients suggests that CTLs target mutated HSPCs rather than nonmutated HSPCs. However, careful follow-up may be needed in the case of elderly patients in whom age-related somatic mutations can precede 6pLOH in HSPCs.

Supplementary Material

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and donors and their physicians, including M. Yamaguchi (Ishikawa Prefectural Central Hospital of Kanazawa) and N. Sugimori (Kanazawa University Hospital), for contributing to this study, and the Advanced Preventive Medical Sciences Research Center (Kanazawa University) for the use of facilities.

This work was supported by Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI): Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (grant no. 24390243) (S.N.); Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (grant no. 26860363) (T.K.); Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (grant no. 17K09007) (T.K.); Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (grant no. 16H06502) (K.H.); and grant no. 221S0002. This work was also supported by the SENSHIN Medical Research Foundation (T.K.), the Hokuriku Bank Research Grant for Young Scientists (T.K.), and the Hokkoku Foundation for Cancer Research (T.K.).

T.I. is a PhD candidate at Kanazawa University and this work is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the PhD.

The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The nucleotide sequence data reported in this article are available in the DDBJ Japanese Genotype-phenotype Archive for genetic and phenotypic human data (accession number JGAS00000000094).

Authorship

Contribution: T.I., T.K., K.H., and S.N. designed the research and wrote the manuscript; T.I. and S.N. collected clinical data and blood samples; T.I., T.K., K.H., N.N., A.T., T.Y., and S.O. performed deep sequencing; and T.I., Y.Z., V.H.N., and N.N. performed the droplet digital PCR and telomere-length measurement using a flow-FISH method.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Shinji Nakao, Department of Hematology, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kanazawa University, 13-1 Takaramachi, Kanazawa, Ishikawa 920-8640, Japan; e-mail: snakao8205@staff.kanazawa-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Scheinberg P, Nunez O, Weinstein B, et al. Horse versus rabbit antithymocyte globulin in acquired aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):430-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bacigalupo A, Bruno B, Saracco P, et al. ; European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Working Party on Severe Aplastic Anemia and the Gruppo Italiano Trapianti di Midolio Osseo (GITMO). Antilymphocyte globulin, cyclosporine, prednisolone, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor for severe aplastic anemia: an update of the GITMO/EBMT study on 100 patients. Blood. 2000;95(6):1931-1934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suzuki T, Kobayashi H, Kawasaki Y, et al. Efficacy of combination therapy with anti-thymocyte globulin and cyclosporine A as a first-line treatment in adult patients with aplastic anemia: a comparison of rabbit and horse formulations. Int J Hematol. 2016;104(4):446-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gluckman E, Esperou-Bourdeau H, Baruchel A, et al. Multicenter randomized study comparing cyclosporine-A alone and antithymocyte globulin with prednisone for treatment of severe aplastic anemia. Blood. 1992;79(10):2540-2546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishiyama K, Chuhjo T, Wang H, Yachie A, Omine M, Nakao S. Polyclonal hematopoiesis maintained in patients with bone marrow failure harboring a minor population of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria-type cells. Blood. 2003;102(4):1211-1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Kamp H, Fibbe WE, Jansen RP, et al. Clonal involvement of granulocytes and monocytes, but not of T and B lymphocytes and natural killer cells in patients with myelodysplasia: analysis by X-linked restriction fragment length polymorphisms and polymerase chain reaction of the phosphoglycerate kinase gene. Blood. 1992;80(7):1774-1780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshizato T, Dumitriu B, Hosokawa K, et al. Somatic mutations and clonal hematopoiesis in aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(1):35-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kulasekararaj AG, Jiang J, Smith AE, et al. Somatic mutations identify a subgroup of aplastic anemia patients who progress to myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 2014;124(17):2698-2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Negoro E, Nagata Y, Clemente MJ, et al. Origins of myelodysplastic syndromes after aplastic anemia. Blood. 2017;130(17):1953-1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maciejewski JP, Sloand EM, Sato T, Anderson S, Young NS. Impaired hematopoiesis in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria/aplastic anemia is not associated with a selective proliferative defect in the glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein-deficient clone. Blood. 1997;89(4):1173-1181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sugimori C, Chuhjo T, Feng X, et al. Minor population of CD55-CD59- blood cells predicts response to immunosuppressive therapy and prognosis in patients with aplastic anemia. Blood. 2006;107(4):1308-1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Afable MG II, Wlodarski M, Makishima H, et al. SNP array-based karyotyping: differences and similarities between aplastic anemia and hypocellular myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2011;117(25):6876-6884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katagiri T, Sato-Otsubo A, Kashiwase K, et al. ; Japan Marrow Donor Program. Frequent loss of HLA alleles associated with copy number-neutral 6pLOH in acquired aplastic anemia. Blood. 2011;118(25):6601-6609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maruyama H, Katagiri T, Kashiwase K, et al. Clinical significance and origin of leukocytes that lack HLA-A allele expression in patients with acquired aplastic anemia. Exp Hematol. 2016;44(10):931-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shen W, Clemente MJ, Hosono N, et al. Deep sequencing reveals stepwise mutation acquisition in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(10):4529-4538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heuser M, Schlarmann C, Dobbernack V, et al. Genetic characterization of acquired aplastic anemia by targeted sequencing. Haematologica. 2014;99(9):e165-e167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaimoku Y, Takamatsu H, Hosomichi K, et al. Identification of an HLA class I allele closely involved in the autoantigen presentation in acquired aplastic anemia. Blood. 2017;129(21):2908-2916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48(3):452-458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Makishima H, Yoshizato T, Yoshida K, et al. Dynamics of clonal evolution in myelodysplastic syndromes. Nat Genet. 2017;49(2):204-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson DR. Differential expression of human major histocompatibility class I loci: HLA-A, -B, and -C. Hum Immunol. 2000;61(4):389-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramsuran V, Kulkarni S, O’huigin C, et al. Epigenetic regulation of differential HLA-A allelic expression levels. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(15):4268-4275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Babushok DV, Duke JL, Xie HM, et al. Somatic HLA mutations expose the role of class I-mediated autoimmunity in aplastic anemia and its clonal complications. Blood Adv. 2017;1(22):1900-1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaiswal S, Fontanillas P, Flannick J, et al. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(26):2488-2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayle A, Yang L, Rodriguez B, et al. Dnmt3a loss predisposes murine hematopoietic stem cells to malignant transformation. Blood. 2015;125(4):629-638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spencer DH, Russler-Germain DA, Ketkar S, et al. CpG island hypermethylation mediated by DNMT3A is a consequence of AML progression. Cell. 2017;168(5):801-816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shlush LI, Zandi S, Mitchell A, et al. ; HALT Pan-Leukemia Gene Panel Consortium. Identification of pre-leukaemic haematopoietic stem cells in acute leukaemia [published correction appears in Nature. 2014;508(7496):420]. Nature. 2014;506(7488):328-333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malcovati L, Gallì A, Travaglino E, et al. Clinical significance of somatic mutation in unexplained blood cytopenia. Blood. 2017;129(25):3371-3378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gibson CJ, Lindsley RC, Tchekmedyian V, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes after autologous stem-cell transplantation for lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(14):1598-1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coombs CC, Zehir A, Devlin SM, et al. Therapy-related clonal hematopoiesis in patients with non-hematologic cancers is common and associated with adverse clinical outcomes. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21(3):374-382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takahashi K, Wang F, Kantarjian H, et al. Preleukaemic clonal haemopoiesis and risk of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms: a case-control study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(1):100-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yasuda T, Ueno T, Fukumura K, et al. Leukemic evolution of donor-derived cells harboring IDH2 and DNMT3A mutations after allogeneic stem cell transplantation [letter]. Leukemia. 2014;28(2):426-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sugimori C, Mochizuki K, Qi Z, et al. Origin and fate of blood cells deficient in glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein among patients with bone marrow failure. Br J Haematol. 2009;147(1):102-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baerlocher GM, Sloand EM, Young NS, Lansdorp PM. Telomere length in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria correlates with clone size. Exp Hematol. 2007;35(12):1777-1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beier F, Balabanov S, Buckley T, et al. Accelerated telomere shortening in glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-negative compared with GPI-positive granulocytes from patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) detected by proaerolysin flow-FISH. Blood. 2005;106(2):531-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karadimitris A, Araten DJ, Luzzatto L, Notaro R. Severe telomere shortening in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria affects both GPI- and GPI+ hematopoiesis. Blood. 2003;102(2):514-516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robertson JD, Gale RE, Wynn RF, et al. Dynamics of telomere shortening in neutrophils and T lymphocytes during ageing and the relationship to skewed X chromosome inactivation patterns. Br J Haematol. 2000;109(2):272-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.