Abstract

Peptide oligomers offer versatile scaffolds for the formation of potent antimicrobial agents due to their high sequence versatility, inherent biocompatibility, and chemical tunability. Though many methods exist for the formation of peptide-based macrocycles (MCs), increasingly pervasive in commercial antimicrobial therapeutics, the introduction of multiple looped structures into a single peptide oligomer remains a significant challenge. Herein, we report the utilization of dynamic hydrazone condensation for the versatile formation of single-, double-, and triple-loop peptide MCs using simple dialdehyde or dihydrazide small-molecule cross-linkers, as confirmed by MALDI-TOF MS, HPLC, and SDS-PAGE. Furthermore, incorporation of aldehyde-containing side chains onto peptides synthesized from hydrazide C-terminal resins resulted in tunable peptide MC assemblies formed directly upon resin cleavage post solid-phase peptide synthesis. Both of these types of dynamic covalent assemblies produced significant enhancements to overall antimicrobial properties when introduced into a known antimicrobial peptide, buforin II, when compared to the original unassembled sequence.

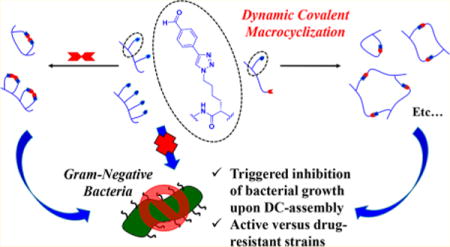

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

The recent and rapid evolution of antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains has led to the unfortunate, undeniable need for novel therapeutics to tackle this systemic problem.1–3 One approach takes inspiration from cationic antimicrobial peptides (CAMPs), integral components of the innate human immune system that ward off infections. Peptides offer a promising alternative to small-molecule antibiotics because their large sequence diversity and chemical tunability make it challenging for bacterial strains to develop resistance.4,5 However, developing resistance is still possible, and potential ramifications of utilizing CAMPs as broad-spectrum antibiotics stem from the possibility of compromising essential immune system responses that utilize natural CAMPs.6

One alternative is to incorporate unnatural functionalities into amino acid side chains as a means of disguising the CAMPs while still retaining their potent antimicrobial properties.7,8 This tactic complements those that utilize unnatural backbone structures to mimic CAMPs such as β-peptides,9,10 peptoids,11,12 and oligothioetheramides,13–15 to name a few. In contrast, dynamic combinatorial chemistry provides a highly convergent approach for the high-throughput screening of a large library of drug candidates through dynamic exchange of reversible covalent bonding moieties.16–20

The incorporation of dynamic covalent (DC) functionalities into biologically active CAMPs and CAMP mimics could provide a marriage of these two principles, offering a simple approach for incorporation of noncanonical functionalities as well as induction of topological transitions. DC functionalities have been incorporated into peptide oligomers leading to interesting applications, such as templated assembly of fluorophores,21 α-helix formation,22 macrocyclization,23 peptide–peptide ligation,24 self-replication,25 formation of catenanes,26 and formation of β-hairpin mimics.26 Very recently, our group reported the facile incorporation of aldehyde and hydrazide functionalities using solid-phase copper-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition (SP-CuAAC) “click” reactions (Scheme 1).27 Alkyne derivatives of these functionalities are “clicked” onto azidolysine (AzK) amino acid residues incorporated via solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS).

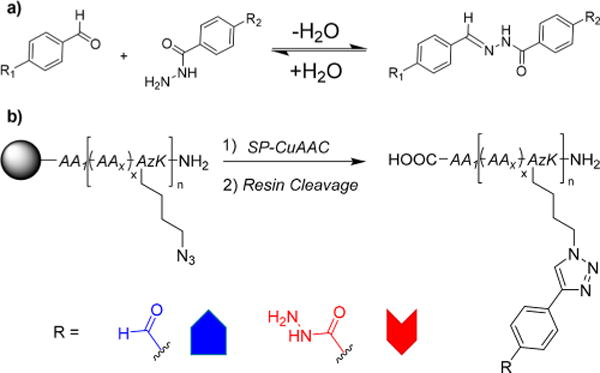

Scheme 1.

(a) Reversible Condensation of Hydrazides onto Aldehydes and (b) Solid-Phase Copper-Catalyzed Azide–Alkyne Cycloaddition (SP-CuAAC) Incorporation of Unnatural, Dynamic Covalent (DC) Aldehyde and Hydrazide Functionalities into Peptide Oligomers Containing Unnatural Azidolysine (AzK) Amino Acid Residues

When these complementary peptides are mixed, the aldehyde and hydrazide side groups rapidly react in aqueous environments to form unnatural peptide quaternary structures linked by dynamic hydrazone bonds. These unique topological quaternary structures include simple macrocycles (MCs), multi-loop macrocycles (MLCs), zipper-like assemblies, and ladder polymers. Interestingly, upon DC assembly, these abiotic peptide quaternary structures were found to increase overall antimicrobial efficiency versus Staphylococcus aureus when compared to their linear components. Of these various topological structures, the templated ladder polymers and single-loop MCs showed the most dramatic enhancements in activity. These enhancements led to overall modest antimicrobial effectiveness, as the peptide oligomers were not specifically designed to perform as antibiotics. Nonetheless, the observed trend motivated us to explore this phenomenon further.

Herein, we demonstrate an expansion of our previous work, showing the ability to induce DC assembly of aldehyde- and hydrazide-containing peptide oligomers using simple small-molecule cross-linkers. This approach allows for the formation of MCs when combined with dialdehyde (DiAl) or dihydrazide (DiHy) peptides or MLCs when mixed with tetra- or hexafunctionalized (TetAl/Hy and HexAl/Hy, respectively) oligomers. Additionally, we utilized hydrazide C-terminal resins (HyRes) as a means to synthesize peptide oligomers containing both hydrazide (on C-terminus post resin cleavage) and aldehyde (through SP-CuAAC) functionalities. Upon resin cleavage, these peptides spontaneously cyclize/oligomerize into various structures, depending on the overall spacing of the DC functionalities. Lastly, the effect of these various cyclization strategies on the antimicrobial properties of buforin II, a naturally occurring CAMP, was tested versus various bacterial strains, including two antibiotic-resistant strains, showing dramatically enhanced antimicrobial effectiveness when cyclized.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Peptide–Small Molecule Macrocyclizations

Several of the peptides synthesized in our previous report were used as models to examine the effect of using small-molecule cross-linkers to induce cyclization (Table 1). DiAl and DiHy peptides were found to rapidly cyclize (ca. 1–3 h) when introduced to small-molecule dialdehydes or dihydrazides at 0.5–3.0 mM concentrations. This is indicated by the presence of one dominant mass ion in the MALDI-TOF MS of these various peptide macrocyclization reactions analyzed without purification (Figure 1a,b). Four DiAl and DiHy peptides were studied with different amino acid (AA) spacing between the DC functionalities (ca. 2, 4, 6, and 8 AAs spaced for DiAl/Hy1–4, respectively). The tabulated observed and theoretical mass ions for all reported MALDI-TOF MS analysis can be found the Supporting Information.

Table 1.

Model DC Peptides Utilized for Cyclization Studies Including Peptides with 2, 4, and 6 Aldehyde or Hydrazide Functionalities (X = Al or Hy, Respectively)

| peptide | sequence |

|---|---|

| DiX1 | N-RTRXFTXGRYF-C |

| DiX2 | N-RTXRFTGXRY-C |

| DiX3 | N-RXTRFTGRXY-C |

| DiX4 | N-XRTRFTGRYXG-C |

| TetX1 | N-RTXVXTXRXY-C |

| TetX2 | N-XGXTDHRLDSXGXE-C |

| TetX3 | N-XIHEXQNRXSARXVTW-C |

| HexX | N-XRLTXTFSXSFTXGTRXSGTXLRTXTRE-C |

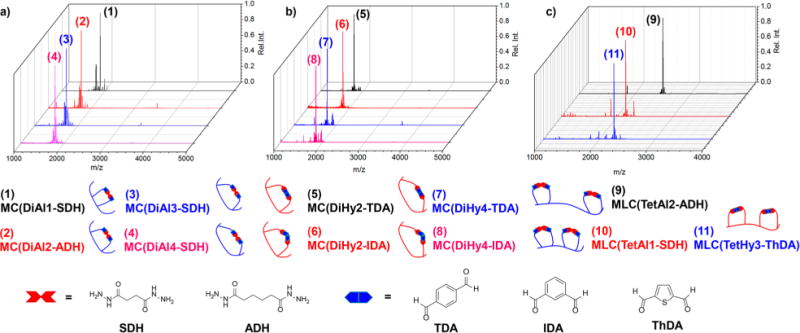

Figure 1.

MALDI-TOF MS of macrocycles (MCs; a and b) and multi-loop macrocycles (MLCs; c) with two loops formed upon reaction of DiAl/Hy and TetAl/Hy peptides, respectively, with small-molecule cross-linkers. These small molecules include flexible, aliphatic dihydrazides and rigid aromatic dialdehydes all showing efficient cyclization. All reactions were conducted at c = 1.0 mM in either 1:1 water:acetonitrile (a and c) or 1:1 PBS buffer (pH = 7.4):acetonitrile (b).

For cyclizations of DiAl2, 3, and 4 with flexible dihydrazide linkers, i.e., succinic dihydrazide (SDH) and adipic dihydrazide (ADH), complete conversion was observed in the MALDI-TOF MS, as evidenced by the complete disappearance of starting material. DiAl1, the smallest of the MCs formed with only 2 AAs spaced between aldehydes, showed a small amount of starting material, which is believed to be consequence of ionization. The conversion of the peptide macrocyclizations for DiAl1 and DiAl4 was also monitored by HPLC (Figure 2a–d), showing complete conversion to the cyclic product as evidenced by the shift in retention time from 18.9 and 18.1 min to 18.7 and 16.6 min, respectively. (All reported analytical HPLCs are 30 min gradient runs from 5% to 95% acetonitrile in water with 0.1 vol% formic acid background.) Additionally, the presence of one sharp peak in the crude reaction mixture after 2 h of reaction nicely portrays the fast, quantitative conversion of this cyclization strategy. Further evidence of the quantitative nature of this macrocyclization strategy is supported by 1H NMR, where we observe the complete disappearance of the chemical shifts associated with the aldehyde protons at ∼10.6 ppm upon cyclization of DiAl4 with ADH (Figure S1). Peptide reaction solutions remained stable over the course of monitoring for 10 days in 1:1 water:acetonitrile, demonstrating the overall usefulness of this cyclization strategy.

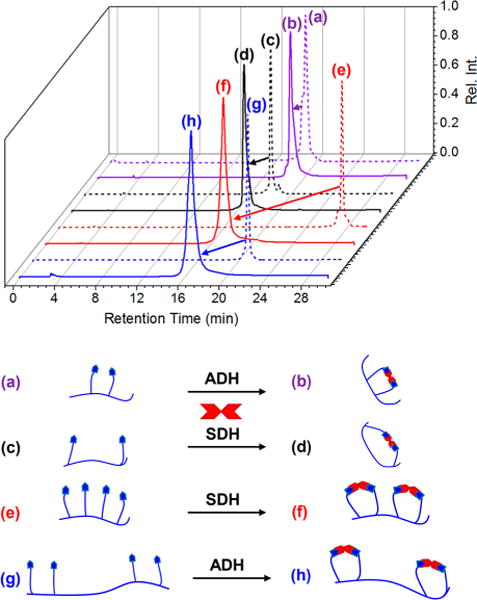

Figure 2.

Analytical HPLC chromatograms monitored at 254 nm absorbance of linear DiAl1 (a), DiAl4 (c), TetAl1 (e), and TetAl2 (g) along with the peptides macrocyclized with ADH (b and h) or SDH (c and f) showing quantitative conversion to the corresponding DC-MC or DC-MLC when reacting for 2 h at c = 1.0 mM in 1:1 water:acetonitrile.

Mixing TetAl DC-peptides with the same cross-linker molecules showed high-efficacy formation of double-loop MLCs (Figure 1c) with quantitative conversions. DC macrocyclization of TetAl derivative TetAl1, with equally spaced aldehyde units every other AA, as well as TetAl2, with two aldehyde units at either termini spaced by one AA, with SDH or ADH occurred very efficiently, as evidenced by MALDI-TOF MS. Further evidence of quantitative conversion was demonstrated using HPLC (Figure 2e–h), where the DC macrocyclization of TeAl1 and TetAl2 causes a shift in retention time when allowed to react with SDH or ADH. The presence of only one distinct peak for these reactions is again indicative of the formation of one distinct product, even though the possibility of different cyclization products is present for the formation of double-loop MLCs. For example, the presence of four aldehyde moieties on the peptide oligomer results in the potential for several different cross-linking possibilities, but the dynamic nature of the hydrazone linkage is hypothesized to allow for the most thermodynamically favored product to form through reversible exchange.

DiHy1–4, TetHy2, and TetHy3 were found to macrocyclize when mixed with rigid aromatic dialdehyde cross-linkers but with some loss of efficacy (see Figure S2). The DiHy peptides cyclizations often display the presence of other mass ions in the MALDI-TOF MS associated with reaction of the N-terminus with the dialdehyde cross-linkers to form an imine. Switching the solvent system to 1:1 PBS buffer (pH = 7.4):acetonitrile reduced the abundance of side reactions for macrocyclization of DiHy peptides but did not eliminate them in all cases, as evidenced by HPLC. Further discussion of these cyclizations can be found in the Supporting Information (section VIII). These macrocyclizations displayed one peak in the MALDI-TOF MS associated with product formation (Figure 1b,c), but due to the potential for side reactions to occur we mainly focused on cyclizations of aldehyde-containing DC peptides.

Reactions between HexAl and small-molecule dihydrazide cross-linkers resulted in gel formation due to the propensity to cross-link peptides intermolecularly. This property may hold interesting application potential in the formation of self-healable peptide hydrogels, but that is not the focal point of this study. When employing buffered systems, the HexHy macrocyclizations precipitated completely from solution. Dialdehyde cross-linkers, however, reacted more selectively, forming triple-loop MLCs when mixed with HexHy in 1:1 water:acetonitrile (Figure S4). The analytical HPLC and MALDI-TOF MS of HexHy support the quantitative formation of MLC(HexHy +TDA) and MLC(HexHy+ThDA) (where TDA = terephthalaldehyde and ThDA = 2,5-thiophenedicarboxaldehyde), similar to the aforementioned examples. This approach provides a facile method for forming controlled macrocyclic topologies with multiple ring structures built into macromolecular architectures.

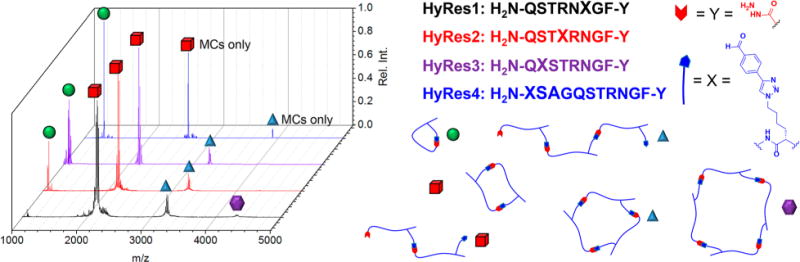

Hydrazide C-Terminal Resin (HyRes) Peptides

As a means to incorporate both aldehyde and hydrazide DC functionalities into a single peptide, we utilized a commercially available 2-chlorotrityl resin with an appended acyl hydrazide that becomes accessible post acid cleavage (HyRes) in place of the C-terminal carboxylate. Peptides were synthesized using this SPPS resin with aldehydes, incorporated using SP-CuAAC, spaced from the hydrazide terminus to varying degrees. HyRes1–4 increase the spacing between DC functionalities in ascending order, with 2, 4, 6, and 10 AAs spacing, respectively (Figure 3). This degree of spacing greatly altered the assembly process for these HyRes peptides, as revealed by MALDI-TOF MS. All HyRes peptides were dissolved at various concentrations (c = 0.05–25.0 mM) in 1:1 water:acetonitrile to observe the effect of concentration on the adopted DC assemblies. Surprisingly, the concentration played little role in the assembly process, with only small changes observed via MALDI-TOF MS or SDS-PAGE (Figures S5 and S6, respectively).

Figure 3.

DC peptides with aldehyde side chains synthesized on hydrazide C-terminal resins (HyRes) assemble into various macrocyclic and oligomeric structures (shown experiments were from c = 3.3 mM solutions), as characterized by MALDI-TOF MS, based on the number of amino acids between DC functionalities. The four peptide synthesized, HyRes1–4, are ordered by increasing number of AA spacing (2, 4, 6, and 10, respectively). The adopted DC assemblies include intramolecular macrocycles (green sphere), linear/macrocyclic dimers (red cube), linear/macrocyclic trimers (blue triangle), and macrocyclic tetramers (purple hexagon).

For HyRes1, the short relative spacing for aldehyde and hydrazide groups highly disfavors intramolecular macrocyclization, with the peptide almost completely adopting dimeric macrocyclic/oligomeric DC assemblies. Additionally, HyRes1 assembled into trimeric macrocyclic/oligomeric assemblies, as demonstrated by MALDI-TOF and SDS-PAGE, which decreased in abundance as a function of concentration. Transitioning from HyRes2 to HyRes4 showed a continuous increase in intramolecular macrocyclization of the aldehyde side group with the hydrazide terminus, with this DC assembly predominating for HyRes4. Furthermore, for HyRes1–3, mass ions corresponding to macrocyclic and linear dimers/trimers were clearly observable, whereas HyRes4 was found to adopt only macrocyclic DC assemblies.

To study the effect of incorporating more rigid or more flexible AAs into the HyRes sequence, two additional model HyRes peptides were synthesized with incorporated proline or glycine AA residues, respectively (Figure S8). HyRes2Flex was synthesized with the same sequence as HyRes2, except with presumably the most flexible and freely rotating AA (glycine) incorporated in between DC functionalities. Additionally, five adjacent proline AAs were incorporated into a HyRes peptide 12mer (HyResPro5), similar length as HyRes4, to see if rigidifying the backbone would favor linear oligomerization. Surprisingly, neither sequence manipulation had much effect on the overall adopted DC assemblies, with HyRes2flex predominantly adopting dimer macrocyclic/oligomeric assemblies, similar to HyRes2, and HyResPro5 assembling into mostly intramolecular MCs, similar to HyRes4.

Antimicrobial DC-Buforin Assemblies

As previously mentioned, the DC assembly process was found to enhance antimicrobial properties of model peptides in our previous report.25 Because these previously studied peptides were not specifically designed for use as antimicrobial agents, their assemblies displayed modest activities. Still, this discovery prompted us to test the effect of DC assembly on a naturally occurring CAMP sequence, buforin II. This 21mer peptide was first isolated from an Asian toad species, Bufo bufo gargarizans, and has been shown to inhibit cellular function of bacterial organisms upon cell membrane penetration.28,29 Furthermore, buforin II exhibits good selectivity toward bacterial organisms over human red blood cells, as reported by Kumar and coworkers.8 These are desirable properties from a therapeutic standpoint, which contributed to our choice of this sequence to screen.

Five DC-buforin II peptides were synthesized using SPPS and SP-CuAAC with two, three, and four DC-functionalities incorporated. Additionally, one HyRes buforin peptide was synthesized with the aldehyde incorporated at the N-terminus (Table 2). One of the true benefits to this method for cyclization is the versatile ability to screen a variety of different preformed peptide tertiary structures by utilizing various cross-linking agents. This versatility should mesh nicely with high-throughput screening of novel therapeutic agents using peptide scaffolds. For this study, we screened the various MC and MLC assemblies described as well as two DC quaternary assemblies from our previous report (vide infra).

Table 2.

Designed Antimicrobial Buforin II Peptides with Two, Three, or Four DC Functionalities Incorporated into the Sequence (X = Al or Hy)

| peptide | sequence |

|---|---|

| DiX buforin | N-XTRSSRAGLQFPVGRVHRLLRXK-C |

| TriX buforin | N-XTRSSRAGLQFPXVGRVHRLLRXK-C |

| TetAl buforin | N-AlTRSSRAAlGLQFPVGRAlVHRLLRAlK-C |

| HyRes buforin | N-AlTRSSRAGLQFPVGRVHRLLRKF-Hy |

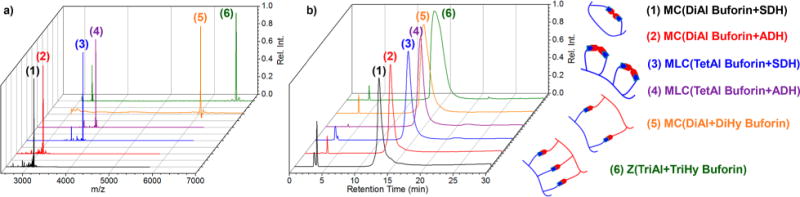

The DC-buforin assemblies were first characterized using the typical techniques: MALDI-TOF MS and HPLC (Figure 4). Overall, the trend was similar to that observed as in the model DC-peptide assemblies, with the aldehyde-containing buforin peptides (DiAl and TetAl) cyclizing very efficiently when reacting with either SDH and ADH, as evidenced by the presence of one distinct mass ion in the MALDI-TOF and one sharp peak in the HPLC chromatogram. This also marks the largest peptide MC formed in this study, with 20 AA residues between the two DC functionalities, further demonstrating the overall versatility of this cyclization strategy.

Figure 4.

MALDI-TOF MS (a) and analytical HPLC traces (b; monitored at 254 nm) of DC assemblies for antimicrobial buforin II peptides with two, three, and four aldehydes or hydrazides incorporated, including MC assemblies with DiAl buforin (1–2), MLC assemblies with TetAl buforin (3,4), DiAl + DiHy buforin intermolecular MC (5), and TriAl + TriHy buforin zipper assembly (6).

The macrocyclizations of DiHy buforin with TDA, IDA (isophthalaldehyde), or ThDA in 1:1 PBS buffer (pH = 7.4):acetonitrile displayed additional mass ions in the MALDI-TOF MS, again associated with incomplete cyclizations as well as N-terminus imine condensation, even after 3 days. Also, the HPLC traces displayed several peaks, especially when reacted with TDA, again believed to be associated with different byproducts formed. Furthermore, some observed masses corresponded to hydrolyzed hydrazide functionalities after 3 days in solution suggesting decreased stability in comparison to the cyclizations of the DiAl peptides. This would decrease their overall usefulness as antimicrobial therapeutics.

Finally, two quaternary topologies were also chosen for our antimicrobial studies, formed in an analogous manner as from our previous report, including the intermolecular MC and zipper (Z) assemblies formed upon DC -reaction between DiAl +DiHy buforins and TriAl+TriHy buforins, respectively. The MALDI-TOF MS displayed predominant mass ions associated with the desired products, with some observed starting material believed to be formed upon ionization. The analytical HPLC displayed no observable starting material, shifting the retention time between each starting material’s retention time in both cases. The slightly broadened chromatographic peaks may be indicative of formation of other topological structures, although only the MC and zipper assemblies were observed in the MALDI-TOF MS.

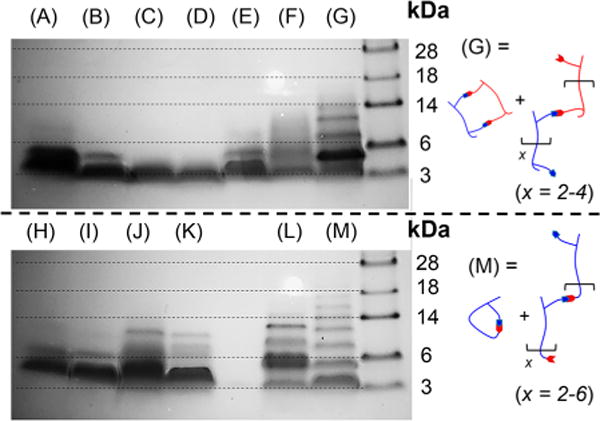

To further confirm the formation of buforin DC assemblies, SDS-PAGE was performed using tricine-SDS buffer systems for the efficient separation of peptides based on molecular weight (MW) from 3 to 30 kDa (Figure 5).30 For the DiAl, TriAl, and TetAl buforin peptides alone (lanes A, H, and J), some dimerization can be observed as a consequence of imine condensation of the N-terminus onto the aldehyde side groups. This is consistent with the results reported previously. The macrocyclization reactions of DiAl buforin with SDH and ADH (lanes C and D) conducted in 1:1 acetonitrile:water showed a single narrow band, ruling out the presence of the dimerized DiAl byproduct. The macrocyclization reactions of DiHy buforin with TDA and ThDA (lanes E and F), run in 1:1 PBS buffer:acetonitrile, displayed some N-terminus dimerization via SDS-PAGE, as evidenced by the higher MW band, consistent with our results observed previously. The formation of MLC-buforin assemblies through reaction of TetAl buforin with SDH was confirmed using SDS-PAGE (lane K) as well, showing one distinct, narrow band associated with the cyclized product.

Figure 5.

Tricine SDS-PAGE of antimicrobial buforin DC peptides and assemblies after reacting for 3 days at 3.0 mM: DiAl (A), DiHy (B), MC(DiAl+SDH) (C), MC(DiAl+ADH) (D), MC(DiHy+TDA) (E), MC(DiHy+ThDA) (F), DiAl+DiHy (G; oligomer and MC), TriAl (H), TriHy (I), TetAl (J), MLC(TetAl+SDH) (K), Z(TriAl +TriHy) (L), and HyRes buforin (M; oligomers and MC).

The buforin DC quaternary structures and HyRes buforin displayed interesting patterns in the SDS-PAGE, suggesting that oligomerization was occurring. For the reaction between DiAl+DiHy buforin, the desired macrocyclic product (lane G; theoretical MW = 6030 Da) clearly predominates, as evidenced by the dark band slightly below the 6 kDa peptide reference marker. However, three other bands were observed in the higher MW region believed to be either linear oligomers or larger macrocyclic products. This is different than what we have observed previously, suggesting that increasing the spacing between DC functionalities begins to favor oligomerization over cyclization.

In a similar manner, the HyRes buforin peptide displayed even higher MW oligomerization, although only intramolecular MC assemblies were observed via MALDI-TOF MS. This is not too surprising, however, because the ablation efficiencies are much higher for lower MW species in MALDI-TOF, causing low MW products to predominate. The sequence-defined oligomerization reached a degree of polymerization of x = 6, but the predominant band still appeared to be the lowest MW intramolecular MC product. Again, it is hard to delineate whether the observed bands are associated with linear oligomers or larger MC products. Similarly, the reaction between TriAl+TriHy buforin also displayed higher MW bands, which again are believed to be associated with oligomerization. These buforin peptide assemblies are the longest and highest MW structures attempted for this DC assembly process, and the large overall spacing between DC functionalities is believed to be the cause of the oligomerization.

Enhancement of Antimicrobial Activity through DC Assembly

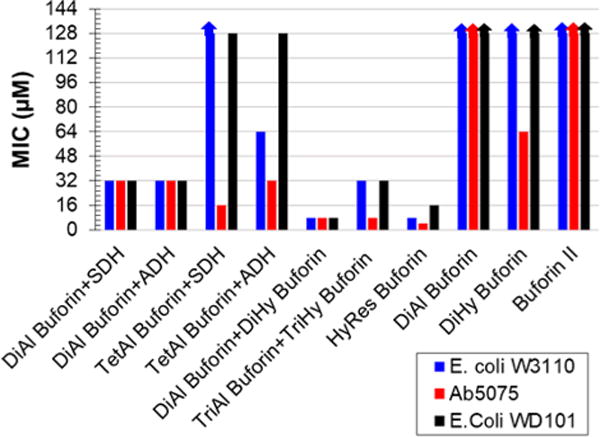

The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of each linear DC peptide, DC assembly, and positive control buforin II unaltered was determined for three Gram-negative strains: Escherichia coli W3110 (wild-type), the isogenic CAMP-resistant mutant WD101,31 and multi-drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (Ab) 507532 (Figure 6). Additionally, these samples were screened against Gram-positive multi-drug-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) but were found to have no activity. MIC determination was conducted using standard methods.33

Figure 6.

MIC values (μM) of buforin DC assemblies, DC peptides, and buforin II versus wild-type E. coli W3110, drug-resistant A. baumannii 5075, and colistin-resistant E. coli WD101 conducted in Mueller-Hinton broth showing a turn-on in antimicrobial activity upon DC assembly. with the crude reactions of TriAl+TriHy buforin, DiAl +DiHy buforin, and HyRes buforin performing the best. Arrows indicate activities greater than 128 μM which were not measured.

For all Gram-negative bacteria studied, the DC assemblies displayed vastly enhanced antimicrobial properties when compared to the uncyclized DC peptides and the unaltered control buforin II. Buforin II activity was previously reported using an agar trypticase soy broth with MIC = 16 μM versus E. coli W3110.28,29 However, we found buforin II had no antimicrobial activity (ca. MIC > 128 μM) versus the aforementioned Gram-negative bacteria when tested by standard Mueller-Hinton broth assay. Similarly, the linear DC peptides DiAl/Hy and TriAl/Hy displayed little to no activity in Mueller-Hinton broth, with the lowest MIC = 64 μM versus Ab5075 for DiHy, TriAl, and TriHy buforin. (For more plotted MIC values of linear DC peptides and cyclizing agents, see Figure S10.) All linear DC peptides showed no activity (ca. MIC > 128 μM) versus either E. coli strain.

Remarkably, upon DC assembly, many of the peptide samples became highly active versus the bacterial strains tested, in particular the multi-drug–resistant A. baumannii strain Ab5075. Collectively, the macrocyclizations of DiAl buforin with SDH or ADH (ca. MIC = 32 μM versus all strains) outperformed the MICs formed from DiHy buforin peptides with dialdehyde cross-linkers. This is not too surprising, considering the lower overall stability of the DiHy buforin cyclizations which may be contributing to the lower activities. When cyclized with IDA, DiHy buforin showed the highest turn-on in antimicrobial effectiveness but still had relatively modest activities (ca. MIC = 64, 32, and 64 μM for E. coli W3110, Ab5075, and E. coli WD101, respectively; see Supporting Information). The TetAl buforin MLC derivatives displayed low antimicrobial efficacy versus both E. coli strains but were effective against Ab5075 with MIC = 16 and 32 μM when cyclized with SDH or ADH, respectively.

The most efficient antimicrobial agents of the DC assemblies tested were the two DC peptide quaternary assemblies (i.e., DiAl+DiHy and TriAl+TriHy buforin) and HyRes buforin, showing large increases in antimicrobial activity versus all strains tested. Interestingly, these three samples were found to oligomerize in solution, forming higher MW sequence-defined polymers mixed with macrocyclic/zipper-like DC assemblies. The crude reaction mixture of DiAl+DiHy buforin displayed the most consistently effective antimicrobial properties, with MIC = 8 μM for all Gram-negative strains tested. The DC assembly with TriAl+TriHy buforin also showed efficient antimicrobial activity versus Ab5075, with MIC = 8 μM and decent activity versus E. coli strains with MIC = 32 μM. The lowest MIC value measured for the DC buforin assemblies was that of the HyRes buforin peptide, with MIC = 8, 4, and 16 μM effectiveness versus E. coli W3110, Ab5075, and E. coli WD101, respectively.

The overall effectiveness of these DC buforin assembles versus E. coli WD101 portrays the impact of this strategy for developing antimicrobial agents. This E. coli strain is resistant to CAMPs, including polymixins,31 which are used as last line antibiotic treatments.34 DC assembly of DiAl+DiHy buforin proved to be very effective versus this resistant strain of E. coli with MIC = 8 μM, with HyRes buforin coming in second (MIC = 16 μM). This suggests that the DC assembly process can enhance CAMP activity to overcome traditional resistance mechanisms.

The antimicrobial activity for buforin II is achieved through the unusual mechanism of penetration through the cell membrane of bacterial cells without membrane disruption, followed by interacting with specific cellular factors.35 The key components of the peptide sequence responsible for cell permeation include the hinged proline region as well as the α-helical segment on the C-terminal end of the peptide sequence. The DC-cross-linking of buforin II is hypothesized to stabilize these specific tertiary structure-enabling motifs, allowing for enhanced cell permeability and leading to overall increases in antimicrobial efficiencies. In addition to this hypothesis, we also cannot rule out potential changes to the mechanistic pathways for antimicrobial activity. Clearly, this hypothesis will require further studies for conformation, but the dramatic increase in antibiotic activity found for our DC-cross-linking warrants such future work.

CONCLUSION

Herein, we report the use of small-molecule cross-linkers to induce topological transitions in peptides containing complementary DC functionalities (i.e., aldehydes and hydrazides). We also utilized commercially available resins for the design and synthesis of HyRes peptides with aldehydes and hydrazides. With these various peptides, we were able to construct peptide-based MCs and MLCs with one, two, or three loops per peptide. Furthermore, peptides with large spacing between complementary DC functionalities were shown to form sequence-defined polymers with MWs reaching ∼14 kDa.

This DC assembly process interestingly showed an enhancement of the overall antimicrobial activity of peptide systems when employing the well-known CAMP buforin II. These assemblies were found to be very efficient at inhibiting the growth of Gram-negative, drug-resistant bacterial strains, leading to potential applications as peptide-based therapeutics and broad-spectrum antibiotics. Future work includes the further development of DiAl, TetAl, and HyRes CAMPs along with the synthesis of novel cross-linkers to further screen the potential impact of ring size, amphiphilicity, and CAMP sequence on the antimicrobial effectiveness of peptide structures. Furthermore, we are exploring the combination of peptides with different properties to monitor the effect of this combination on the overall biological activity of the assembly.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The presented work was supported financially under the DAPRA Fold-Fx program (N66001-14-2-4051), NIH (AI25337), and the Welch Regents Chair (F-0046 and F-1870). We would also like to thank Maria Persons of the University of Texas at Austin Proteomics Facility and Ian Riddington of the Mass Spectrometry Facility at UT Austin for their aid in MALDI-TOF MS and HRMS acquisition.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.8b00046.

Synthetic procedures, characterization of peptide oligomers, additional characterization of DC-assemblies, and procedures for antimicrobial screening, including Tables S1 and S2 and Figures S1–S11 (PDF)

ORCID

James F. Reuther: 0000-0001-5611-0290

Eric V. Anslyn: 0000-0002-5137-8797

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Cabello FC. Environ Microbiol. 2006;8:1137–1144. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ling LL, Schneider T, Peoples AJ, Spoering AL, Engels I, Conlon BP, Mueller A, Schaberle TF, Hughes DE, Epstein S, Jones M, Lazarides L, Steadman VA, Cohen DR, Felix CR, Fetterman KA, Millett WP, Nitti AG, Zullo AM, Chen C, Lewis K. Nature. 2015;517:455–459. doi: 10.1038/nature14098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright GD. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:175–186. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loose C, Jensen K, Rigoutsos I, Stephanopoulos G. Nature. 2006;443:867–869. doi: 10.1038/nature05233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peschel A, Sahl H-G. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:529–536. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersson DI, Hughes D, Kubicek-Sutherland JZ. Drug Resist Updates. 2016;26:43–57. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuriakose J, Hernandez-Gordillo V, Nepal M, Brezden A, Pozzi V, Seleem MN, Chmielewski J. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2013;52:9664–9667. doi: 10.1002/anie.201302693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meng H, Kumar K. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15615–15622. doi: 10.1021/ja075373f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Porter EA, Weisblum B, Gellman SH. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:7324–7330. doi: 10.1021/ja0260871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raguse TL, Porter EA, Weisblum B, Gellman SH. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:12774–12785. doi: 10.1021/ja0270423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher KJ, Turkett JA, Corson AE, Bicker KL. ACS Comb Sci. 2016;18:287–291. doi: 10.1021/acscombsci.6b00039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kapoor R, Wadman MW, Dohm MT, Czyzewski AM, Spormann AM, Barron AE. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:3054–3057. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01516-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porel M, Alabi CA. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:13162–13165. doi: 10.1021/ja507262t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Porel M, Thornlow DN, Artim CM, Alabi CA. ACS Chem Biol. 2017;12:715–723. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Porel M, Thornlow DN, Phan NN, Alabi CA. Nat Chem. 2016;8:590–596. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehn J-M, Eliseev AV. Science. 2001;291:2331–2332. doi: 10.1126/science.1060066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rowan SJ, Cantrill SJ, Cousins GRL, Sanders JKM, Stoddart JF. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2002;41:898–952. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020315)41:6<898::aid-anie898>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sadownik JW, Ulijn RV. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2010;21:401–411. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corbett PT, Leclaire J, Vial L, West KR, Wietor J-L, Sanders JKM, Otto S. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3652–3711. doi: 10.1021/cr020452p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jin Y, Yu C, Denman RJ, Zhang W. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:6634–6654. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60044k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rocard L, Berezin A, De Leo F, Bonifazi D. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2015;54:15739–15743. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haney CM, Loch MT, Horne WS. Chem Commun. 2011;47:10915–10917. doi: 10.1039/c1cc12010g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haney CM, Horne WS. J Pept Sci. 2014;20:108–114. doi: 10.1002/psc.2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruff Y, Garavini V, Giuseppone N. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:6333–6339. doi: 10.1021/ja4129845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sadownik JW, Mattia E, Nowak P, Otto S. Nat Chem. 2016;8:264–269. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lam RTS, Belenguer A, Roberts SL, Naumann C, Jarrosson T, Otto S, Sanders JKM. Science. 2005;308:667–669. doi: 10.1126/science.1109999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reuther JF, Dees JL, Kolesnichenko IV, Hernandez ET, Ukraintsev DV, Guduru R, Whiteley M, Anslyn EV. Nat Chem. 2018;10:45–50. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park CB, Kim HS, Kim SC. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;244:253–257. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park CB, Kim MS, Kim SC. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;218:408–413. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schagger H. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:16–22. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trent MS, Ribeiro AA, Doerrler WT, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43132–43144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106962200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacobs AC, Thompson MG, Black CC, Kessler JL, Clark LP, McQueary CN, Gancz HY, Corey BW, Moon JK, Si Y, Owen MT, Hallock JD, Kwak YI, Summers A, Li CZ, Rasko DA, Penwell WF, Honnold CL, Wise MC, Waterman PE, Lesho EP, Stewart RL, Actis LA, Palys TJ, Craft DW, Zurawski DV. mBio. 2014;5:e01076–14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01076-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiegand I, Hilpert K, Hancock REW. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:163–175. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts KD, Azad MAK, Wang J, Horne AS, Thompson PE, Nation RL, Velkov T, Li J. ACS Infect Dis. 2015;1:568–575. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.5b00085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park CB, Yi K-S, Matsuzaki K, Kim MS, Kim SC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8245–8250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.150518097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.