Abstract

Rats and mice exposed to repeated stress or a single severe stress exhibit a sustained increase in energetic, endocrine and behavioral response to subsequent novel mild stress. This study tested whether the hyper-responsiveness was due to a lowered threshold of response to corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) or an exaggerated response to a standard dose of CRF. Male Sprague Dawley rats were subjected to 3 hours of restraint on each of 3 consecutive days (RRS) or were non-restrained Controls. RRS caused a temporary hypophagia, but a sustained reduction in body weight. Eight days after the end of restraint rats received increasing third ventricle doses of CRF (0- 3.0 μg). The lowest dose of CRF (0.25 μg) increased corticosterone release in RRS, but not Control rats. Higher doses caused the same stimulation of corticosterone in the two groups of rats. Fifteen days after the end of restraint rats were food deprived during the light period and received increasing third ventricle doses of CRF at the start of the dark period. The lowest dose of CRF inhibited food intake during the first hour following infusion in RRS, but not Control rats. All other doses of CRF inhibited food intake to the same degree in both RRS and Control rats. The lowered threshold of response to central CRF is consistent with the chronic hyper-responsiveness to CRF and mild stress in RRS rats during the post-restraint period.

Keywords: HPA axis, food intake, rats, stress-responsiveness

Introduction

Rats subjected to 3 hours of restraint stress experience a sustained reduction in body weight (Rybkin et al., 1997). Repetition of restraint on three consecutive days (RRS) maximizes the weight loss (Harris et al., 2002) which is maintained for at least 3 months (Harris et al., 2006). Down-regulation of body weight has also been reported for rats exposed to other stressors including social defeat (Meerlo et al., 1996) and immobilization (Valles et al., 2000). RRS also causes sustained changes in the endocrine response to stress represented by an exaggerated corticosterone release in response to mild stress, but the same response as controls to more severe stress (Harris et al., 2004). Similar observations have been made in rats exposed to 2 hours of immobilization (Belda et al., 2008) or scrambled footshock every 90 seconds for 30 minutes (Belda et al., 2004). In addition, it is well established that acute or chronic stress modifies behavior in the post-stress period. For example, social defeat causes a long-term inhibition of social interaction (Watt et al., 2009) and impairment of working memory (Novick et al., 2013). These data suggest that exposure to stress causes a sustained change in the sensitivity or responsiveness of central mechanisms that control behavioral and physiological responses to subsequent stressors.

Hyperreactivity could be achieved either by lowering the threshold for response, or by amplifying the response to a standard concentration of receptor agonist. We measured the effect of corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) injected into the third ventricle on corticosterone release and on food intake of rats that had previously been subjected to RRS. We previously reported that third ventricle injection of the CRFR1 antagonist antalarmin prevents the sustained reduction in body weight of RRS of rats (Chotiwat and Harris, 2008), which implies that the long-term effects of RRS are initiated in an area adjacent to the ventricle.

Methods

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Augusta University and followed National Institute of Health guidelines for care and use of laboratory animals. Eighty male Sprague Dawley rats (Envigo RMS, IN) entered the study in three cohorts in which all treatment groups were equally represented. They were housed individually in hanging wire mesh cages at 21°C with lights on for 12 hours a day from 6.00 a.m. with free access to food (Harlan Teklad Rodent Diet 8604) and water except where specified. After one week of adaptation they were fitted with third ventricle guide cannula as described previously (Chotiwat and Harris, 2008). Cannula placement was verified seven days later by infusion of 20 ng angiotensin II in 2 μl of sterile saline. Rats that drank water within 2 min of infusion were included in the experiment. All infusions were delivered from Hamilton syringes controlled by an infusion pump (PHD 2000 Infusion pump, Harvard Apparatus, MA). Four rats failed to drink following the angiotensin II injection and 3 additional rats were removed later in the study when their cannulas became loose. Rats were given 2 days to recover from the angiotensin II infusion before the experiment started.

Daily body weights and food intake corrected for spillage were recorded for 6 days and then the rats were divided into two weight-matched groups. One group was subjected to RRS. At 8.00 a.m. they were placed in a Perspex restraining tubes (21.6 × 6.4 cm, Plas Labs, MI) in an experimental room. Controls were housed in shoe box cages without food or water in the same room. After 3 hours all rats were returned to their home cage. Restraint was repeated on three consecutive days. The first day of RRS was Day 0 of the experiment, food intake was measured until 5 days after the end of restraint and body weights were recorded throughout the experiment. On Day 8 food was removed from the cages at 7.00 a.m. Control and RRS groups were each subdivided into five weight-matched groups. Starting at 9.00 a.m. a small blood sample was collected from the tail of each rat immediately before they received a 2 ul 3rd ventricle infusion of saline or 0.25, 0.5, 1.0 or 3.0 μg CRF. This was considered Time 0. Additional blood samples were collected exactly 30, 60, 90 and 120 minutes after infusion. Food was returned to cage at the end of blood sampling. Samples were centrifuged and serum corticosterone concentration measured (Corticosterone Double Antibody – 125I RIA Kit Rats & Mice, MP Biomedicals, OH).

On Day 15 food was removed from the cages at 7.00 a.m. Control and RRS rats were each subdivided into 5 weight matched groups. Starting at 5.00 p.m. each rat received a 2 ul third ventricle infusion of saline, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0 or 3.0 ug CRF. Food was returned to the cages at 6.00 p.m. and intake was recorded 1, 2, 4 and 6 hours after infusion. Body weight was monitored for an additional three days.

Significant differences in weight gain, food intake and corticosterone were determined by repeated measures analysis of variance using Statistica version 9.0 (StatSoft, OK) and post-hoc Duncans Multiple range test. P<0.05 was considered significant. Effect size comparisons were performed for ANOVA (Eta-squared = effect sum of squares/total sum of squares). Single measure comparisons were made by unpaired t-test assuming equal variance and effect size calculated as Cohen's d.

Results

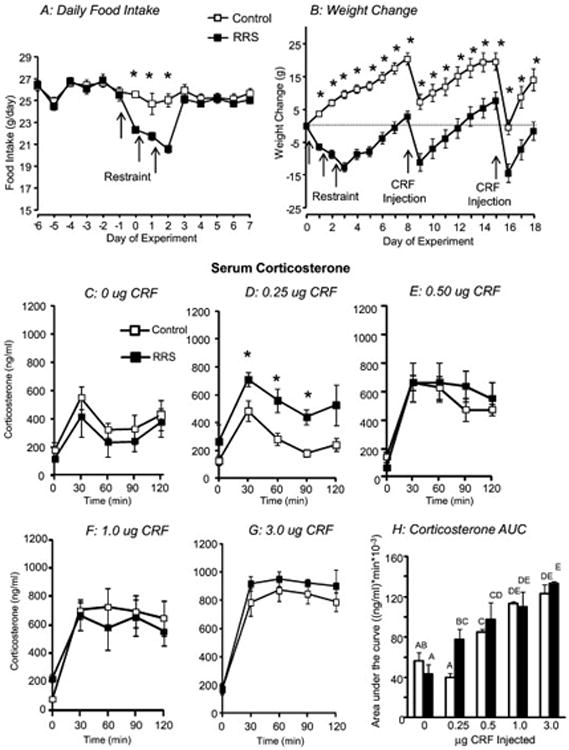

Food intake of RRS rats was inhibited on the days of restraint, but then returned to control levels (Figure 1A). Because these rats did not compensate for the hypophagia, total intake during Days 0-8 was significantly lower in RRS than Control rats (188 + 2 vs 203 + 3, df=73, Cohen's d = 0.68). Control and RRS rats weighed the same on Day 0 (Control: 324 + 3g, RRS: 318 + 3g), but RRS rats lost 16.4 + 1.4 g during RRS whereas Controls gained 5.4 + 1.9 g (RRS: P<0.001 df=1, F=134, Eta-squared = 0.91; Day: P<0.4, df= 2, F = 1, Eta-squared = 0.001; RRS × Day: P<0.001, df=2, F=72, Eta-squared = 0.08). The difference in weight was maintained to the end of the experiment because the two groups gained weight at the same rate following RRS (Figure 1B). All Control and RRS rats lost weight during the 24 hours following CRF infusion, but there was no significant effect of CRF dose in either group. They gained weight again within 48 hours, but there was no effort to compensate for the weight loss.

Figure 1. Food intake, body weight and HPA activation in RRS and control rats.

Daily food intake (A) and weight change (B) in control and RRS rats. RRS rats were subjected to 3 hours of restraint on Days 0, 1 and 2 of the experiment and Control and RRS rats were injected with different doses of CRF on Days 8 and 15. Data are means + sem for 36 or 37 rats. Serum corticosterone measured 8 days after the end of RRS during the 2 hours following a 3rd ventricle infusion of different doses of CRF is shown in Panels C- G and Panel H shows area under the curve for serum corticosterone. Data are means + sem for groups of 5 or 6 rats. Asterisks indicate significant differences between Control and RRS rats. Values for area under the curve that do not share a common superscript are significantly different.

Third ventricle infusions of CRF caused a dose-dependent increase in serum corticosterone. There was no difference in corticosterone release in Control and RRS rats receiving 0, 0.5, 1.0 or 3.0 μg CRF (Figure 1C, E-G), but corticosterone was significantly higher in RRS than Control rats infused with 0.25 μg CRF (Figure 1D: RRS: P<0.008, df =1, F=11, Eta-squared = 0.43; Time: P<0.001, df=4, F=12, Eta-squared = 0.54; Interaction: P<0.7, df =4, F= 0.5, Eta-squared = 0.02). Calculation of area under the curve indicated that 0.25 μg CRF had no effect on corticosterone in Control rats compared with those receiving 0 μg CRF, whereas it stimulated corticosterone release in RRS rats to the same levels as that achieved by 0.5 μg CRF (Figure 1H). Because peak corticosterone concentration continued to increase with CRF dose it was not possible to determine whether we had reached maximal response in rats injected with 3.0 μg CRF. Area under the curve was not different for rats receiving 1.0 or 3.0 μg CRF, but because corticosterone remained elevated at 120 min this plateau was likely an artifact of the sampling protocol.

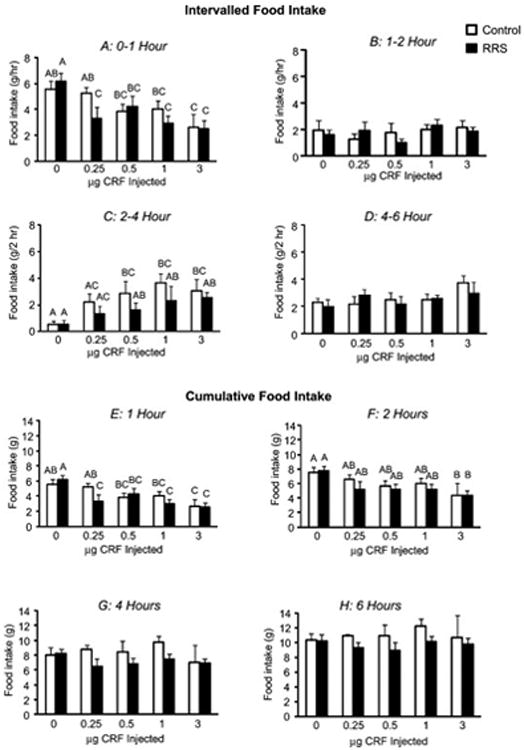

Third ventricle infusion of CRF on Day 15 of the experiment caused a dose-dependent inhibition of food intake in rats that had been food deprived during the day (Figure 2). During the first hour after the infusion both control and RRS rats infused with 0.5, 1 or 3 μg CRF ate significantly less than rats infused with saline. A dose of 0.25 μg CRF significantly inhibited food intake in RRS, but not Control rats (Figure 2A). This initial inhibition was compensated for between 2 and 4 hours after infusion (Figure 2C) and cumulative intake was the same for all of the rats at 4 and 6 hours post-infusion (Figure 2G and H).

Figure 2. The Effect of third ventricle CRF on food intake of RRS and Control rats.

Intervalled (panels A-D) and cumulative food intake (Panels E-H) of RRS and Control rats that received third ventricle infusions of increasing doses of CRF at the start of the dark period 15 days after the end of RRS. Values on a specific axis that do not share a common superscript are significantly different. Data are means + sem for groups of 5 or 6 rats.

Discussion

Sustained changes in behavior and HPA activity following acute stress are well documented for rodent models and it has been reported that exposure to a single severe stress desensitizes the HPA axis to that stress, but increases reactivity to novel stressors (Belda et al., 2008). The neural basis of the chronic effects of acute stress has not been fully elucidated but the impact on neurogenesis and methylation of DNA are being investigated and involvement of noradrenergic (Curtis et al., 1995) and serotonergic systems (Berton et al., 1999) is well established. Noradrenergic neurons in the locus coeruleus have been implicated in the emotional and cognitive responses to stress (Sullivan et al., 1999) and recently the sustained increase in anxiety following repeated social stress has been associated with adrenergic-dependent inflammation in this area (Wohleb et al., 2011).

We have reported that RRS rats maintain a reduced body weight compared with their controls and have an exaggerated sensitivity to mild stress in the post-stress period. Hyperreactivity of the HPA axis has also been reported for animals subjected to more natural stressors such as overcrowding (Ortiz et al., 1985). This study suggests that exposure to RRS lowers the threshold of response to CRF because the lowest dose tested here (0.25 μg) increased corticosterone and inhibited food intake of RRS, but not control rats whereas there was no difference between the two groups in their response to higher doses of CRF. These results are consistent with our previous observation that RRS rats show an exaggerated corticosterone release and reduce food intake in response to the mild stress of an intraperitoneal injection of saline, whereas the response to the more extreme physiologic stress of 2-deoxyglucose-induced hypoglycemia is the same for control and RRS rats (Harris et al., 2004).

We did not test the molecular basis for the lowered threshold of response. Inhibition of CRF binding protein expression would result in an apparent lowering of the response threshold because a greater amount of free CRF would be available to bind to receptors (Behan et al., 1995), however, it has been reported that restraint stress stimulates expression of the binding protein, which would attenuate CRF response (Herringa et al., 2004). We have reported that activation of CRFR1 during RRS initiates at least some of the long-term effects of stress (Chotiwat and Harris, 2008) and we (Harris et al., 2006) and others (Imaki et al., 1996) have shown that restraint stress causes an acute increase in expression of CRFR1 in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus of rats. This could enhance the effect of CRF on HPA activity and food intake, but the increase in receptor expression is not maintained in the post-RRS period (Harris et al., 2006). Additionally, it has recently been reported that HPA reactivity is independent of CRFR1 activation (Belda et al., 2012). Recovery of homeostasis following acute stress is achieved by glucocorticoid negative feedback on the hypothalamus and pituitary, but Belda (Belda et al., 2012) also demonstrated that HPA reactivity is not due to a failure of negative feedback. Therefore, the increased sensitivity to low doses of CRF may be due to a post-receptor event, rather than the dynamics of CRF receptor binding which would be consistent with conclusions made from an earlier study measuring CRF-evoked discharge of locus coeruleus neurons in rats subjected to repeated sessions of foot-shock (Curtis et al., 1995).

Highlights.

Three hours of restraint for 3 days (RRS) makes rats hyper-responsive to novel stress

RRS rats show an exaggerated corticosterone response to low doses of central CRF

RRS rats show an exaggerated hypophagic response to low doses of central CRF

High doses of CRF produce the same changes in RRS and control rats

Post-restraint responsiveness to stress is due to a lower threshold for response to CRF

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant MH068281 awarded to RBSH]. The author thanks Matt Hinnant for his assistance with this experiment.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: The author has no potential conflict of interest associated with publication of this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Behan DP, De Souza EB, Lowry PJ, Potter E, Sawchenko P, Vale WW. Corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) binding protein: a novel regulator of CRF and related peptides. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1995;16:362–382. doi: 10.1006/frne.1995.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belda X, Marquez C, Armario A. Long-term effects of a single exposure to stress in adult rats on behavior and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responsiveness: comparison of two outbred rat strains. Behav Brain Res. 2004;154:399–408. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belda X, Rotllant D, Fuentes S, Delgado R, Nadal R, Armario A. Exposure to severe stressors causes long-lasting dysregulation of resting and stress-induced activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1148:165–173. doi: 10.1196/annals.1410.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belda X, Daviu N, Nadal R, Armario A. Acute stress-induced sensitization of the pituitary-adrenal response to heterotypic stressors: independence of glucocorticoid release and activation of CRH1 receptors. Horm Behav. 2012;62:515–524. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berton O, Durand M, Aguerre S, Mormede P, Chaouloff F. Behavioral, neuroendocrine and serotonergic consequences of single social defeat and repeated fluoxetine pretreatment in the Lewis rat strain. Neuroscience. 1999;92:327–341. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00742-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chotiwat C, Harris RB. Antagonism of specific corticotropin-releasing factor receptor subtypes selectively modifies weight loss in restrained rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R1762–1773. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00196.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis AL, Pavcovich LA, Grigoriadis DE, Valentino RJ. Previous stress alters corticotropin-releasing factor neurotransmission in the locus coeruleus. Neuroscience. 1995;65:541–550. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00496-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris RB, Mitchell TD, Simpson J, Redmann SM, Jr, Youngblood BD, Ryan DH. Weight loss in rats exposed to repeated acute restraint stress is independent of energy or leptin status. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;282:R77–88. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2002.282.1.R77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris RB, Gu H, Mitchell TD, Endale L, Russo M, Ryan DH. Increased glucocorticoid response to a novel stress in rats that have been restrained. Physiol Behav. 2004;81:557–568. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris RB, Palmondon J, Leshin S, Flatt WP, Richard D. Chronic disruption of body weight but not of stress peptides or receptors in rats exposed to repeated restraint stress. Horm Behav. 2006;49:615–625. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herringa RJ, Nanda SA, Hsu DT, Roseboom PH, Kalin NH. The effects of acute stress on the regulation of central and basolateral amygdala CRF-binding protein gene expression. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2004;131:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaki T, Naruse M, Harada S, Chikada N, Imaki J, Onodera H, Demura H, Vale W. Corticotropin-releasing factor up-regulates its own receptor mRNA in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1996;38:166–170. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(96)00011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meerlo P, Overkamp GJ, Daan S, Van Den Hoofdakker RH, Koolhaas JM. Changes in Behaviour and Body Weight Following a Single or Double Social Defeat in Rats. Stress. 1996;1:21–32. doi: 10.3109/10253899609001093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick AM, Miiller LC, Forster GL, Watt MJ. Adolescent social defeat decreases spatial working memory performance in adulthood. Behav Brain Funct. 2013;9:39. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-9-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz R, Armario A, Castellanos JM, Balasch J. Post-weaning crowding induces corticoadrenal hyperreactivity in male mice. Physiol Behav. 1985;34:857–860. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(85)90003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybkin II, Zhou Y, Volaufova J, Smagin GN, Ryan DH, Harris RB. Effect of restraint stress on food intake and body weight is determined by time of day. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:R1612–1622. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.5.R1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan GM, Coplan JD, Kent JM, Gorman JM. The noradrenergic system in pathological anxiety: a focus on panic with relevance to generalized anxiety and phobias. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:1205–1218. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00246-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valles A, Marti O, Garcia A, Armario A. Single exposure to stressors causes long-lasting, stress-dependent reduction of food intake in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;279:R1138–1144. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.3.R1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt MJ, Burke AR, Renner KJ, Forster GL. Adolescent male rats exposed to social defeat exhibit altered anxiety behavior and limbic monoamines as adults. Behav Neurosci. 2009;123:564–576. doi: 10.1037/a0015752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohleb ES, Hanke ML, Corona AW, Powell ND, Stiner LM, Bailey MT, Nelson RJ, Godbout JP, Sheridan JF. beta-Adrenergic receptor antagonism prevents anxiety-like behavior and microglial reactivity induced by repeated social defeat. J Neurosci. 2011;31:6277–6288. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0450-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]