Abstract

Background

Recent clinical studies have shown that skin autofluorescence (AF) levels are significantly associated with diabetic complications. In contrast, data regarding the relationships between skin AF and chronic heart failure (CHF) are limited. The aim of this study was to clarify the clinical significance of skin AF in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) with CHF.

Methods

This cross-sectional study enrolled 257 outpatients with type 2 DM with CHF who were treated medically (96 men and 161 women; mean age, 79 ± 7 years). Associations between skin AF and various clinical parameters were examined.

Results

Incidence of skin AF in patients with a history of hospitalization due to HF was significantly higher than in those without a history of hospitalization due to HF (3.0 ± 0.5 AU vs. 2.7 ± 0.5 AU, respectively, P < 0.001). Significant positive correlations were found between skin AF and various clinical parameters, such as E/e′ as a maker of left ventricular diastolic function (r = 0.30, P < 0.001), high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T levels as a marker of myocardial injury (r = 0.45, P < 0.001), reactive oxygen metabolite levels as an oxidative stress marker (r = 0.31, P < 0.001), and cardio-ankle vascular index as a marker of arterial function (r = 0.38, P < 0.001). Furthermore, multiple regression analyses showed that these clinical parameters (E/e′ (β = 0.25, P < 0.001)), high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T levels (β = 0.30, P < 0.001), cardio-ankle vascular index (β = 0.21, P < 0.001), reactive oxygen metabolite levels (β = 0.15, P < 0.01), and a history of hospitalization due to HF (β = 0.23, P < 0.001) were independent variables when skin AF was used as a subordinate factor.

Conclusion

The findings of this study showed that skin AF may be a determining factor for prognosis in patients with type 2 DM with CHF. Further investigations in a large prospective study, including intervention therapies, are required to validate the results of this study.

Keywords: Skin autofluorescence, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Chronic heart failure, Heart failure admission, Left ventricular diastolic function, High-sensitivity cardiac troponin T, Oxidative stress, Cardio-ankle vascular index

Introduction

In recent years, the incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) and chronic heart failure (CHF) has been increasing worldwide due to extended life expectancy or lifestyle changes. In addition, the condition of a number of patients was complicated with type 2 DM and CHF in clinics [1, 2]. Some basic and clinical studies have shown that cardiac function is affected by DM due to various factors, including high blood glucose levels, insulin resistance, renin-angiotensin system, or other problems [3, 4]. Furthermore, some studies have reported that patients with type 2 DM with HF had poor prognosis compared with those without DM and with a history of HF [5, 6]. Therefore, considering adequate diagnosis and therapy for patients with type 2 DM with CHF is important.

Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) play an important role in the pathophisiology of DM. Among the methods used to evaluate AGEs, skin autofluorescence (AF) is known to be a simple and reliable marker of AGEs in vivo, and recent clinical studies have indicated that skin AF levels are significantly associated with diabetic complications, such as macro- or microvascular disease [7-9]. However, data regarding the relationships between skin AF and pathogenesis of CHF are limited. Therefore, this cross-sectional study attempted to clarify the clinical significance of skin AF in patients with type 2 DM with CHF.

Materials and Methods

Patients

A total of 257 outpatients were enroolied between November 2013 and October 2017 with type 2 DM with CHF who had medical treatment at the Hitsumoto Medical Clinic. CHF was defined based on ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults [10]. The patients included 96 (37.8%) and 161 (62.2%) men and women, respectively, with a mean age of 79 ± 7 years (mean ± standard deviation). All participants provided informed consent, and the local ethics committee approved the study protocol.

Skin AF measurement

Skin AF was measured using a commercial device (AGE Reader™; DiagnOptics, Groningen, the Netherlands), as previously described [11, 12]. AF was defined as the average light intensity per nanometer between 300 and 420 nm. Skin AF levels were expressed in arbitrary units (AU). All measurements were performed at the volar side of the lower arm, approximately 10 - 15 cm below the elbow, while the patients were in a sitting position. The value of pentosidine, a major component of AGEs, was measured using skin biopsy at the volar side of the lower arm and seemed to correlate with skin AF [13]. The validity and reliability of skin AF levels in the Japanese population measured using this method has been established previously [12].

Evaluation of clinical parameters

Various clinical parameters such as classic risk factors of cardiovascular disease, history of ischemic heart disease, blood glucose-related parameters, echocardiographic findings, kidney function, brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T (hs-cTnT) levels, oxidative stress, and arterial function were evaluated. Obesity was identified using body mass index (BMI), calculated as the weight (kg) divided by the squared height (m2). Current smoking was defined as smoking at least one cigarette per day over the previous 28 days. History of ischemic heart disease was defined as patients with history of myocardial infarction and/or angiography-proven significant stenosis. Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg, or those taking antihypertensive medications. Dyslipidemia was defined as low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels ≥ 140 mg/dL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels ≤ 40 mg/dL, triglyceride levels ≥ 150 mg/dL, or based on an ongoing treatment for dyslipidemia. Glucose and insulin levels were measured using the glucose oxidase method and an enzyme immunoassay, respectively. To measure insulin resistance, HOMA-IR was calculated using the following equation [14]: HOMA-IR = fasting glucose concentration (mg/dL) × fasting insulin concentration (µg/mL)/405. The hemoglobin A1c levels were expressed using the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program. Standard technique for echocardiography was performed using HI VISION Avius (Hitachi Medical Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), and valvular heart disease was diagnosed based on the guideline of the Japanese Circulation Society (Guidelines for the Clinical Application of Echocardiography (JCS 2010)). Valvular heart disease consisted of aortic or mitral valve disease (aortic stenosis, aortic regurgitation, mitral stenosis, and mitral regurgitation). Left ventricular wall thickness, left ventricular extended period diameter, left ventricular ejection fraction, left atrial dimension, and E/e′ were also measured by echocardiography. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the adjusted Modification of Diet in the Renal Disease Study equation, which was proposed by the working group of the Japanese Chronic Kidney Disease Initiative [15]. BNP levels were measured using a commercial kit (SHIONOSPOT Reader; Shionogi & Co., Osaka, Japan), and hs-cTnT levels were also measured using a commercial kit (Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland) [16]. As an oxidative stress maker in vivo [17], the reactive oxygen metabolite (d-ROM) test was performed using a commercial kit (Diacron, Grosseto, Italy). In this study, cardio-ankle vascular index (CAVI) as a physiological marker of arterial function was measured using a VaSera CAVI instrument (Fukuda Denshi, Tokyo, Japan), following the previously described methods [18]. Briefly, the brachial and ankle pulse waves were determined using inflatable cuffs, with the pressure maintained between 30 and 50 mm Hg to ensure that the cuff pressure had a minimal effect on systemic hemodynamics. Systemic blood and pulse pressures were simultaneously determined, with the participant in a supine position. CAVI was measured after a 10-min rest in a quiet room. The accuracy of CAVI is known to be less in the presence of non-sinus rhythm or obstructive arteriosclerosis. Therefore, patients with chronic atrial fibrillation and/or obstructive arteriosclerosis (ankle-brachial index < 0.9) were excluded. The mean values of the left and right sides were used for statistical evaluation of the CAVI.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Stat View-J 5.0 (HULINKS, Tokyo, Japan). Data in the study were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Between-group comparisons were performed using Student’s t-test. Simple regression analysis was performed using the Spearman rank correlation, and a multivariate analysis was performed using multiple regression or multiple logistic regression analyses. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

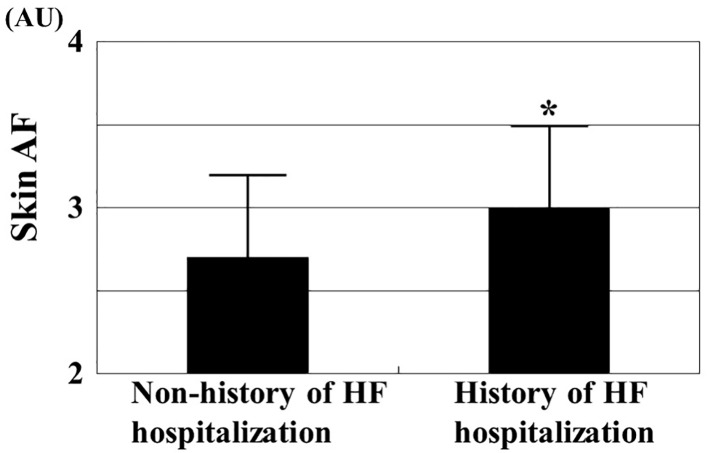

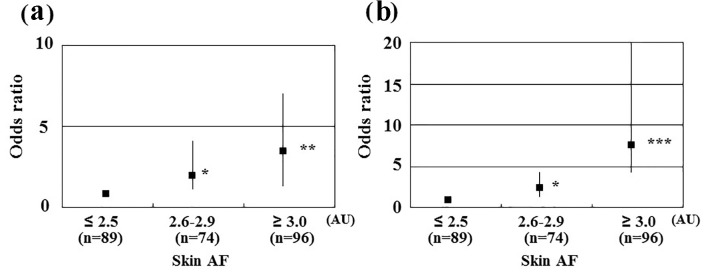

Table 1 summarizes the patient characteristics. The mean skin AF levels were 2.8 ± 0.5 AU (range, 1.7 - 4.0 AU). In total, 60 patients (23%) had a history of hospitalization due to HF. Figure 1 shows the comparisons of skin AF levels between patients with and without a history of hospitalization due to HF. The skin AF levels in patients with a history of hospitalization due to HF were significantly higher than those without a history of hospitalization due to HF (3.0 ± 0.5 AU vs. 2.7 ± 0.5 AU, respectively, P < 0.001), although the mean age was similar between the two groups. Table 2 presents the correlations between skin AF and various clinical parameters. Age, smoking habits, presence of ischemic heart disease, HbA1c, left atrial dimension, E/e′, eGFR, BNP, hs-cTnT, d-ROMs test, and the CAVI were significantly correlated with skin AF. Table 3 summarizes the results of a multiple regression analysis with skin AF as a subordinate factor. Explanatory factors were selected by examining multicollinearity among the variables or by conducting a stepwise method. Hs-cTnT, E/e′, history of hospitalization due to HF, CAVI, d-ROM test, and age were identified as independent variables when skin AF was used as a subordinate factor. The participants were divided into three groups based on their skin AF values, and a multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to describe the simple threshold of skin AF for detecting hospitalization due to HF or high hs-cTnT levels (Fig. 2). Patients with high (≥ 3.0 AU) or moderate skin AF levels (2.6 - 2.9 AU) showed a significantly higher risk (OR, 3.2 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.4 - 7.0), P < 0.01; OR, 2.0 (95% CI: 1.1 - 4.0), P < 0.05, respectively) of detecting hospitalization due to HF than those with low skin AF (≤ 2.5 AU). In contrast, patients with high or moderate ski AF levels had a significantly higher risk (OR, 7.8 (95% CI: 4.1 - 20.0), P < 0.001; OR, 2.2 (95% CI: 1.1 - 4.3), P < 0.05, respectively) of having a high hs-cTnT level (≥ 0.018 ng/mL) than did those with low skin AF.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics.

| n (male/female) | 257 (96/161) |

| Age (years) | 79 ± 7 |

| Skin autofluorescence (AU) | 2.8 ± 0.5 |

| Body mass index | 22.8 ± 0.6 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 30 (12) |

| Ischemic heart disease, n (%) | 39 (15) |

| HF hospitalization, n (%) | 60 (23) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 202 (79) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 139 ± 17 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 81 ± 10 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 172 (67) |

| Fasting blood glucose (mg/dL) | 143 ± 26 |

| HOMA-IR | 2.8 ± 1.8 |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%) | 7.3 ± 1.0 |

| Heart valvular disease, n (%) | 189 (74) |

| IVSTd (mm) | 9.8 ± 1.8 |

| LVDd (mm) | 50.0 ± 3.6 |

| LVEF (%) | 68.8 ± 12.8 |

| LAD (mm) | 42.5 ± 5.6 |

| E/e′ | 9.6 ± 3.7 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 48.4 ± 17.6 |

| Log-BNP (pg/mL) | 2.0 ± 0.3 |

| Log-hs-cTnT (ng/mL) | -2.0 ± 0.3 |

| d-ROMs test (U. CARR) | 336 ± 108 |

| CAVI | 9.7 ± 1.4 |

| Medication | |

| Sulfonylurea, n (%) | 186 (72) |

| Biguanide, n (%) | 41 (16) |

| DPP-4 inhibitor, n (%) | 155 (60) |

| Insulin, n (%) | 26 (10) |

| RAS inhibitor, n (%) | 169 (66) |

| β-blocker, n (%) | 56 (22) |

| Diuretics, n (%) | 40 (16) |

| Statin, n (%) | 159 (62) |

Continuous values are mean ± SD. HF: heart failure; HOMA-IR: homeostasis assessment insulin resistance; IVSTd: interventricular septal thickness at end-diastole; LVDd: left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; LAD: left atrial dimension; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; BNP: brain natriuretic peptide; hs-cTnT: high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T; d-ROMs: derivatives of reactive oxygen metabolites; CAVI: cardio-ankle vascular index; DPP: dipeptidyl peptidase; RAS: renin-angiotensin system.

Figure 1.

Comparisons of skin AF values between patients with and without history of heart failure admission. The skin AF levels in patients with a history of hospitalization due to HF were significantly higher than those without a history of hospitalization due to HF (3.0 ± 0.5 AU vs. 2.7 ± 0.5 AU, respectively, P < 0.001) even though mean age was similar between the two groups (80 ± 7 years vs. 79 ± 7 years, respectively). *P < 0.001 vs. non-history of HF hospitalization. AF: autofluorescence; HF: heart failure; AU: arbitrary units.

Table 2. Relationship Between Skin AF and Various Clinical Parameters.

| r | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (female = 0, male = 1) | -0.01 | 0.065 |

| Age | 0.12 | < 0.05 |

| Body mass index | 0.06 | 0.363 |

| Current smoker (no = 0, yes = 1) | 0.12 | < 0.05 |

| Ischemic heart disease (no = 0, yes = 1) | 0.13 | < 0.05 |

| Hypertension (no = 0, yes = 1) | 0.03 | 0.631 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 0.09 | 0.158 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 0.02 | 0.700 |

| Dyslipidemia (no = 0, yes = 1) | 0.04 | 0.527 |

| Fasting blood glucose | 0.05 | 0.448 |

| HOMA-IR | 0.06 | 0.372 |

| Hemoglobin A1c | 0.16 | < 0.01 |

| Heart valvular disease (no = 0, yes = 1) | 0.05 | 0.433 |

| IVSTd | 0.04 | 0.523 |

| LVDd | 0.03 | 0.563 |

| LVEF | 0.04 | 0.514 |

| LAD | 0.12 | < 0.05 |

| E/e′ | 0.30 | < 0.001 |

| eGFR | -0.16 | < 0.01 |

| Log-BNP | 0.29 | < 0.001 |

| Log-hs-cTnT | 0.45 | < 0.001 |

| d-ROMs test | 0.31 | < 0.001 |

| CAVI | 0.38 | < 0.001 |

| Sulfonylurea (no = 0, yes = 1) | 0.03 | 0.684 |

| Biguanide (no = 0, yes = 1) | 0.04 | 0.507 |

| DPP-4 inhibitor (no = 0, yes = 1) | -0.07 | 0.242 |

| Insulin (no = 0, yes = 1) | 0.02 | 0.811 |

| RAS inhibitor (no = 0, yes = 1) | -0.09 | 0.158 |

| β-blocker (no = 0, yes = 1) | 0.05 | 0.429 |

| Diuretics (no = 0, yes = 1) | 0.03 | 0.679 |

| Statin (no = 0, yes = 1) | -0.02 | 0.701 |

r expressed correlation coefficient. HOMA-IR: homeostasis assessment insulin resistance; IVSTd: interventricular septal thickness at end-diastole; LVDd: left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; LAD: left atrial dimension; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; BNP: brain natriuretic peptide; hs-cTnT: high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T; d-ROMs: derivatives of reactive oxygen metabolites; CAVI: cardio-ankle vascular index; DPP: dipeptidyl peptidase; RAS: renin-angiotensin system.

Table 3. Multiple Regression Analysis for Skin AF.

| Explanatory factor | β | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Log-hs-cTnT | 0.30 | < 0.001 |

| E/e′ | 0.25 | < 0.001 |

| HF hospitalization | 0.23 | < 0.001 |

| CAVI | 0.21 | < 0.001 |

| d-ROMs test | 0.15 | < 0.01 |

| Age | 0.13 | < 0.05 |

| eGFR | -0.08 | 0.144 |

R2 = 0.31. AF: autofluorescence; hs-cTnT: high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T; CAVI: cardio-ankle vascular index; HF: heart failure; d-ROMs: derivatives of reactive oxygen metabolites; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; β: standardized regression coefficient; R2: coefficient of determination.

Figure 2.

Results of multiple logistic regression analysis of heart failure hospitalization or high hs-cTnT levels. (a) Subordinate factor is heart failure hospitalization. Adjustment factors are hs-cTnT, E/e′, CAVI, d-ROMs test, and age. (b) Subordinate factor is high hs-cTnT levels. High hs-cTnT was defined as hs-cTnT ≥ 0.018 ng/mL. Adjustment factors are E/e′, history of heart failure hospitalization, CAVI, d-ROMs test, and age. *P < 0.05 vs. skin AF ≤ 2.5 AU; **P < 0.01 vs. skin AF ≤ 2.5 AU, ***P < 0.001 vs. skin AF ≤ 2.5 AU. hs-cTnT: high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T; CAVI: cardio-ankle vascular index; d-ROMs: derivatives of reactive oxygen metabolites; AU: arbitrary units.

Discussion

Ruigomez et al reported that patients hospitalized with an initial HF diagnosis or those hospitalized due to HF thereafter are at high risk of worse outcomes [19]. In addition, some researchers have observed that patients with DM with a history of hospitalization due to HF had poor prognosis compared with patients without diabetes with a history of hospitalization due to HF [20]. Thus, these reports indicated that early diagnosis or intervention therapy for patients with CHF is important to prevent hospitalization due to HF, particularly in patients with diabetes and CHF. In this study targeting patients with type 2 DM with CHF, the skin AF levels in patients with a history of hospitalization due to HF were significantly higher than in those without. Furthermore, a history of hospitalization due to HF was independently associated with skin AF levels. Thus, skin AF levels were considered as an important target factor to define the prognosis of patients with type 2 DM with CHF.

Hs-cTnT is used as a biomarker to evaluate the degree of myocardial injury in clinics. In addition, some clinical studies have shown the clinical usefulness of hs-cTnT as a prognostic value in patients with CHF [21, 22]. On the contrary, Hofmann et al reported on the relationship between AGE-modified cardiac tissue collagen levels and skin AF and found a significant relationship between cardiac tissue glycation and skin AF [23]. Their report also indicated that the AGE levels found at the volar side of the lower arm seem to reflect the degree of AGE accumulation in the cardiomyocytes. Some researchers have indicated several pathways wherein AGEs or receptors of AGEs (RAGEs) could influence myocardial injury in a diabetes model. Ma et al [24] reported that DM resulted in a significant increase in AGE and RAGE levels in the heart, particularly in the cardiomyocytes, when using mice with streptozotocin-induced DM. They also reported that AGE-induced cardiomyocyte dysfunction was linked to mitochondrial membrane depolarization and reduced GSK-3β inactivation, which are events that can be prevented by RNA interference knockdown of RAGE expression. In addition, Bucciarelli et al indicated that RAGE affected ischemia/reperfusion injury in the diabetic myocardium [25]. On the contrary, recent clinical studies noted the importance of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in the pathogenesis of HF. Furthermore, some researchers have indicated that AGEs or RAGE affected left ventricular diastolic function [26, 27]. Wang et al reported the significant relationship of E/e′ as a marker of left ventricular diastolic function and skin AF in subjects at risk for cardiovascular diseases [28]. The results of these studies also indicate that skin AF levels reflect left ventricular diastolic function in patients with type 2 DM with CHF. Thus, the results of this study and those of previous studies have shown that AGEs and RAGEs are believed to play important roles in myocardial injury or left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in patients with type 2 DM with CHF.

A number of studies have shown the importance of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of CHF. Several pathways wherein oxidative stress leads to myocardial injury have been reported, including dysfunction of the mitochondrial electron transport complex, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase activity, and myocardial cell apoptosis [29, 30]. In contrast, a number of basic and clinical studies have shown a close association between AGEs or RAGEs and oxidative stress. In addition, an association between AGEs or RAGEs and oxidative stress in myocardial cells has been reported [31]. In this study, a significant correlation was observed between skin AF and d-ROM test as a marker of oxidative stress in vivo, suggesting that AGEs or RAGEs and oxidative stress are associated with each other in myocardial cells, and this consequently promotes myocardial injury in patients with type 2 DM with CHF.

In this study, CAVI as one of the physiological markers of arterial function was independently associated with skin AF levels. Basic studies have reported that AGEs or RAGE can induce inflammation, oxidative stress, and calcification in vascular cells, such as endothelial or smooth muscle cells [32-34]. Clinical studies have also indicated a significant association between skin AF and physiological markers of arterial function, including CAVI [35-37]. On the contrary, some researchers have shown the importance of arterial function in the pathogenesis of CHF [38, 39]. Skin AF as a marker of AGE levels in vivo is thus considered as a considerable risk factor for progression of CHF, not only in direct influence for cardiomyocytes but also in arterial function.

Setting a target value for predicting adverse cardiovascular events in the clinical setting would be useful. In this study, the participants were divided into three groups based on the simple cut-off of values of skin AF levels to clarify the clinical significance of skin AF measurements in patients with type 2 DM with CHF, and multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to detect a correlation between hospitalization due to HF or high hs-cTnT levels (≥ 0.018 ng/mL), which has been reported as being the cut-off level for predictive cardiovascular incidence rate in patients with CHF [22]. The results of this study have indicated that patients with skin AF values ≥ 3.0 or from 2.6 - 2.9 exhibited a significantly higher risk of hospitalization due to HF and higher hs-cTnT levels than did those with skin AF values ≤ 2.5. Thus, the results of this study suggest using the cut-off skin AF level of 3.0 or 2.5 to prevent adverse cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 DM with CHF. In contrast, Yamagishi et al reported that AGEs are considered to be markers expressing hyperglycemic memory [40]. Genevieve et al performed a study regarding the association between skin AF and HbA1c levels, and they reported that skin AF level was significantly associated with the means of the last five and 10 HbA1c values [41]. Thus, these reports have shown that we should perform long-term glucose control to prevent adverse cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 DM with CHF.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the medical treatments for DM, CHF, hypertension, and/or dyslipidemia may have affected the study results. Second, the HOMA-IR has limitations as a marker of insulin resistance, particularly in patients with high blood glucose levels, and we included patients with high fasting blood glucose levels. Therefore, additional studies using another accurate insulin resistance marker, such as a glucose clamp test, are warranted to evaluate the clinical significance of insulin resistance in this study design. Third, not every patient underwent coronary angiography or coronary artery computed tomography. Therefore, asymptomatic ischemic heart disease may have remained undetected. Finally, the study design was a single-center cross-sectional study and the sample size was relatively small. Additional prospective studies, including evaluations of interventional therapies, are required to clarify the clinical significance of skin AF in patients with type 2 DM with CHF.

Conclusions

The findings of this study showed that skin AF may be a determining factor for prognosis of patients having type 2 DM with CHF. Further investigations in many prospective studies, including intervention therapies, are required to validate the results of this study.

Conflict of Interest

Author has no conflict of interest.

Grant Support

None.

Financial Disclosure

None.

References

- 1.Kannel WB, Hjortland M, Castelli WP. Role of diabetes in congestive heart failure: the Framingham study. Am J Cardiol. 1974;34(1):29–34. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(74)90089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertoni AG, Tsai A, Kasper EK, Brancati FL. Diabetes and idiopathic cardiomyopathy: a nationwide case-control study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(10):2791–2795. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.10.2791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nasir S, Aguilar D. Congestive heart failure and diabetes mellitus: balancing glycemic control with heart failure improvement. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(9 Suppl):50B–57B. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ingelsson E, Sundstrom J, Arnlov J, Zethelius B, Lind L. Insulin resistance and risk of congestive heart failure. JAMA. 2005;294(3):334–341. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.3.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pocock SJ, Wang D, Pfeffer MA, Yusuf S, McMurray JJ, Swedberg KB, Ostergren J. et al. Predictors of mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(1):65–75. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacDonald MR, Petrie MC, Varyani F, Ostergren J, Michelson EL, Young JB, Solomon SD. et al. Impact of diabetes on outcomes in patients with low and preserved ejection fraction heart failure: an analysis of the Candesartan in Heart failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM) programme. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(11):1377–1385. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hangai M, Takebe N, Honma H, Sasaki A, Chida A, Nakano R, Togashi H. et al. Association of advanced glycation end products with coronary artery calcification in Japanese subjects with type 2 diabetes as assessed by skin autofluorescence. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2016;23(10):1178–1187. doi: 10.5551/jat.30155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hitsumoto T. Impact of hemorheology assessed by the microchannel method on pulsatility index of the common carotid artery in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Med Res. 2017;9(7):579–585. doi: 10.14740/jocmr3031w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rigalleau V, Cougnard-Gregoire A, Nov S, Gonzalez C, Maury E, Lorrain S, Gin H. et al. Association of advanced glycation end products and chronic kidney disease with macroangiopathy in type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29(2):270–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, Jessup M. et al. 2009 focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Circulation. 2009;119(14):e391–479. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meerwaldt R, Links TP, Graaff R, Hoogenberg K, Lefrandt JD, Baynes JW, Gans RO. et al. Increased accumulation of skin advanced glycation end-products precedes and correlates with clinical manifestation of diabetic neuropathy. Diabetologia. 2005;48(8):1637–1644. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1828-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nomoto K, Yagi M, Arita S, Hamada U, Yonei Y. A survey of fluorescence derived from advanced glycation end products in the skin of Japanese: differences with age and measurement location. Anti Aging Med. 2012;9(5):119–124. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meerwaldt R, Graaff R, Oomen PHN, Links TP, Jager JJ, Alderson NL, Thorpe SR. et al. Simple non-invasive assessment of advanced glycation endproduct accumulation. Diabetologia. 2004;47(7):1324–1330. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1451-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28(7):412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imai E, Horio M, Nitta K, Yamagata K, Iseki K, Hara S, Ura N. et al. Estimation of glomerular filtration rate by the MDRD study equation modified for Japanese patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2007;11(1):41–50. doi: 10.1007/s10157-006-0453-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mingels A, Jacobs L, Michielsen E, Swaanenburg J, Wodzig W, van Dieijen-Visser M. Reference population and marathon runner sera assessed by highly sensitive cardiac troponin T and commercial cardiac troponin T and I assays. Clin Chem. 2009;55(1):101–108. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.106427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cesarone MR, Belcaro G, Carratelli M, Cornelli U, De Sanctis MT, Incandela L, Barsotti A. et al. A simple test to monitor oxidative stress. Int Angiol. 1999;18(2):127–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shirai K, Utino J, Otsuka K, Takata M. A novel blood pressure-independent arterial wall stiffness parameter; cardio-ankle vascular index (CAVI) J Atheroscler Thromb. 2006;13(2):101–107. doi: 10.5551/jat.13.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruigomez A, Michel A, Martin-Perez M, Garcia Rodriguez LA. Heart failure hospitalization: An important prognostic factor for heart failure re-admission and mortality. Int J Cardiol. 2016;220:855–861. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.06.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varela-Roman A, Grigorian Shamagian L, Barge Caballero E, Mazon Ramos P, Rigueiro Veloso P, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR. Influence of diabetes on the survival of patients hospitalized with heart failure: a 12-year study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7(5):859–864. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otaki Y, Arimoto T, Takahashi H, Kadowaki S, Ishigaki D, Narumi T, Honda Y. et al. Prognostic value of myocardial damage markers in patients with chronic heart failure with atrial fibrillation. Intern Med. 2014;53(7):661–668. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.53.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aimo A, Januzzi JL Jr, Vergaro G, Ripoli A, Latini R, Masson S, Magnoli M. et al. Prognostic value of high-sensitivity troponin T in chronic heart failure: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Circulation. 2018;137(3):286–297. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.031560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hofmann B, Jacobs K, Navarrete Santos A, Wienke A, Silber RE, Simm A. Relationship between cardiac tissue glycation and skin autofluorescence in patients with coronary artery disease. Diabetes Metab. 2015;41(5):410–415. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma H, Li SY, Xu P, Babcock SA, Dolence EK, Brownlee M, Li J. et al. Advanced glycation endproduct (AGE) accumulation and AGE receptor (RAGE) up-regulation contribute to the onset of diabetic cardiomyopathy. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13(8B):1751–1764. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00547.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 25.Bucciarelli LG, Ananthakrishnan R, Hwang YC, Kaneko M, Song F, Sell DR, Strauch C. et al. RAGE and modulation of ischemic injury in the diabetic myocardium. Diabetes. 2008;57(7):1941–1951. doi: 10.2337/db07-0326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell DJ, Somaratne JB, Jenkins AJ, Prior DL, Yii M, Kenny JF, Newcomb AE. et al. Diastolic dysfunction of aging is independent of myocardial structure but associated with plasma advanced glycation end-product levels. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e49813. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bayraktar A, Canpolat U, Demiri E, Kunak AU, Ozer N, Aksoyek S, Ovunc K. et al. New insights into the mechanisms of diastolic dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2015;49(3):142–148. doi: 10.3109/14017431.2015.1039571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang CC, Wang YC, Wang GJ, Shen MY, Chang YL, Liou SY, Chen HC. et al. Skin autofluorescence is associated with inappropriate left ventricular mass and diastolic dysfunction in subjects at risk for cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s12933-017-0495-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li SY, Yang X, Ceylan-Isik AF, Du M, Sreejayan N, Ren J. Cardiac contractile dysfunction in Lep/Lep obesity is accompanied by NADPH oxidase activation, oxidative modification of sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase and myosin heavy chain isozyme switch. Diabetologia. 2006;49(6):1434–1446. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0229-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boudina S, Abel ED. Diabetic cardiomyopathy, causes and effects. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2010;11(1):31–39. doi: 10.1007/s11154-010-9131-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bodiga VL, Eda SR, Bodiga S. Advanced glycation end products: role in pathology of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Heart Fail Rev. 2014;19(1):49–63. doi: 10.1007/s10741-013-9374-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yan SF, Ramasamy R, Schmidt AM. The RAGE axis: a fundamental mechanism signaling danger to the vulnerable vasculature. Circ Res. 2010;106(5):842–853. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.212217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang JS, Wendt T, Qu W, Kong L, Zou YS, Schmidt AM, Yan SF. Oxygen deprivation triggers upregulation of early growth response-1 by the receptor for advanced glycation end products. Circ Res. 2008;102(8):905–913. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.165308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brett J, Schmidt AM, Yan SD, Zou YS, Weidman E, Pinsky D, Nowygrod R. et al. Survey of the distribution of a newly characterized receptor for advanced glycation end products in tissues. Am J Pathol. 1993;143(6):1699–1712. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Couppe C, Dall CH, Svensson RB, Olsen RH, Karlsen A, Praet S, Prescott E. et al. Skin autofluorescence is associated with arterial stiffness and insulin level in endurance runners and healthy controls - Effects of aging and endurance exercise. Exp Gerontol. 2017;91:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang CC, Wang YC, Wang GJ, Shen MY, Chang YL, Liou SY, Chen HC. et al. Skin autofluorescence is associated with endothelial dysfunction in uremic subjects on hemodialysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0147771. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hitsumoto T. Clinical significance of cardio-ankle vascular index as a cardiovascular risk factor in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Med Res. 2018;10(4):330–336. doi: 10.14740/jocmr3364w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chow B, Rabkin SW. The relationship between arterial stiffness and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a systemic meta-analysis. Heart Fail Rev. 2015;20(3):291–303. doi: 10.1007/s10741-015-9471-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kishimoto S, Kajikawa M, Maruhashi T, Iwamoto Y, Matsumoto T, Iwamoto A, Oda N. et al. Endothelial dysfunction and abnormal vascular structure are simultaneously present in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Int J Cardiol. 2017;231:181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamagishi S, Nakamura K, Imaizumi T. Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and diabetic vascular complications. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2005;1(1):93–106. doi: 10.2174/1573399052952631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Genevieve M, Vivot A, Gonzalez C, Raffaitin C, Barberger-Gateau P, Gin H, Rigalleau V. Skin autofluorescence is associated with past glycaemic control and complications in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. 2013;39(4):349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]