Abstract

Introduction

Children with acute respiratory tract infections (ARTIs) are prescribed up to 11.4 million unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions annually. Inadequate parent–provider communication is a chief contributor, yet efforts to reduce overprescribing have only indirectly targeted communication or been impractical. This paper describes our multisite, parallel group, cluster randomised trial comparing two feasible interventions for enhancing parent–provider communication on the rate of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing (primary outcome) and revisits, adverse drug reactions and parent-rated quality of shared decision-making, parent–provider communication and visit satisfaction (secondary outcomes).

Methods/analysis

We will attempt to recruit all eligible paediatricians and nurse practitioners (currently 47) at an academic children’s hospital and a private practice. Using a 1:1 randomisation, providers will be assigned to a higher intensity education and communication skills or lower intensity education-only intervention and trained accordingly. We will recruit 1600 eligible parent–child dyads. Parents of children ages 1–5 years who present with ARTI symptoms will be managed by providers trained in either the higher or lower intensity intervention. Before their consultation, all parents will complete a baseline survey and view a 90 s gain-framed antibiotic educational video. Parent–child dyads consulting with providers trained in the higher intensity intervention will, in addition, receive a gain-framed antibiotic educational brochure promoting cautious use of antibiotics and rate their interest in receiving an antibiotic which will be shared with their provider before the visit. All parents will complete a postconsultation survey and a 2-week follow-up phone survey. Due to the two-stage nested design (parents nested within providers and clinics), we will employ generalised linear mixed-effect regression models.

Ethics/dissemination

Ethical approval was obtained from the Children’s Mercy Hospital Pediatric Institutional Review Board (#16060466). Results will be submitted for publication in peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

NCT03037112; Pre-results.

Keywords: quality in health care, paediatrics, primary care, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Implements a parent–provider communication intervention based on a previously effective intervention and adapted for feasibility in the US paediatric ambulatory setting.

Works closely with a multicultural group of parents, providers and other stakeholders to ensure feasibility and appropriateness of intervention components, study procedures and study materials in Spanish and English.

Adequately powered to detect differences between the higher and lower intensity interventions, with a 1:1 randomisation of providers to intervention arms and a target sample of 1600 parents/child dyads.

Data on primary outcomes (ie, rates of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing), secondary outcomes (ie, revisits and adverse drug reactions, shared decision-making, quality of parent–provider communication and satisfaction) and potential covariates will yield novel insights into the effectiveness of each intervention.

Provider training was limited to one 20 min session for all providers and one additional 50 min session for providers in the higher intensity arm.

Introduction

Antibiotic overuse and misuse contribute to the development of antibiotic-resistant infections that if left unchecked are estimated to cause 10 million deaths worldwide by 2050.1 In the USA, antibiotic-resistant infections are responsible for at least 23 000 deaths and an additional 2 million infections annually.2 Inappropriate antibiotic use also increases incidence of antibiotic-associated adverse drug reactions (eg, rash, diarrhoea, nausea and vomiting), which result in >140 000 emergency department visits every year.3

The majority of all antibiotic prescribing in the USA occurs in the outpatient setting where children receive 49 million prescriptions annually.4 Children with acute respiratory tract infections (ARTIs) receive >70% of these prescriptions of which 29% are unnecessary (ie, either to treat a viral illness or an unnecessary broad-spectrum antibiotic).4 Despite some improvements, the most recent estimates suggest that antibiotics are prescribed for approximately 50% of ARTIs while it is estimated that only 27% of ARTIs are caused by bacterial infection.5 As a result, children are receiving up to 11.4 million unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions annually.5 Strikingly, an almost identical number was noted in a similar study conducted 16 years earlier (11.1 million unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions), suggesting there are considerable gains still to be made in reducing inappropriate use.6

Inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in the ambulatory setting has many causes, but the interaction between parents/legal guardians (hereafter referred to as parents) and providers is central. For their part, some parents still harbour misconceptions that make them think antibiotics are necessary when they are not.7 Nevertheless, parents generally desire antibiotics for their children only when absolutely necessary8 and do not expect antibiotics for common colds.9 Instead, parents become dissatisfied when providers minimise children’s symptoms, fail to acknowledge parents’ appropriate concerns and/or do not offer a contingency plan if symptoms fail to resolve.10 11

Despite evidence to the contrary, providers perceive significant parental pressure for antibiotics and fear damaging the parent–provider relationship if they withhold prescriptions.12 13 Combined with the ever-increasing time constraints and focus on parent satisfaction ratings inherent in modern clinical practice, these beliefs greatly contribute to ineffective parent–provider communication about antibiotics. When providers perceive that a parent expects or hopes for an antibiotic, they are more likely to prescribe one.14 15 In a study of children with viral ARTIs where no prescription should have been given, providers gave a prescription to 52% of parents they believed were expecting an antibiotic compared with only 9% of parents who they believed were not expecting an antibiotic.16 Adding to this problem is providers’ mistaken belief that they can accurately predict parents’ desires. In fact, providers’ ability to accurately predict parents’ expectation for an antibiotic is significantly worse than chance at 24%–41% concordance.12 16 Even though parents rarely state a desire for antibiotics (1% of the time in clinical recordings), providers report frequent parent demands for antibiotics.17 Providers also mistakenly believe that meeting perceived parental expectations for antibiotics is necessary for parent satisfaction.13 Parental satisfaction, however, is not related so much to whether or not they receive an antibiotic but more to the quality of communication with their provider.10 13 In fact, a recent observational study demonstrated that the use of what they termed ‘positive treatment recommendations’ (ie, comfort care) plus ‘negative treatment recommendations’ (ie, antibiotics will not help) was associated with the highest parent satisfaction.18

Current efforts to improve appropriate antibiotic use have only indirectly targeted parent–provider communication19 20 or have been found to be impractical.21 As described in several meta-analytic and systematic reviews, interventions have typically focused on education about antibiotics for providers or patients.19 20 While many have been successful in increasing knowledge about antibiotics and nationally antibiotic prescribing has evidenced modest reductions,8 22 more effective strategies that go beyond educational targets are needed to reduce overprescribing rates to levels that will have a significant impact. A limited number of studies have been conducted that target parent–provider communication or shared decision-making, and they have already produced superior results.20 Of the communication interventions tested, only one has directly targeted provider perceptions of parental expectations alongside antibiotic education and shared decision-making.23 This study, which employed intensive provider training and a multipage patient–provider interactive educational booklet, resulted in a significant decrease in antibiotic use. The intervention, however, was viewed as burdensome by providers and impractical for most real-world settings.21 Effective, practical interventions are needed that address provider misconceptions about parent expectations, facilitate shared-decision making and improve aspects of communication that are most likely to increase parental satisfaction.

The goal of this study is to compare two feasible interventions for enhancing parent–provider communication to reduce the rate of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing. This study will compare the efficacy of a higher intensity provider education and communication skills intervention to a lower intensity provider education only intervention. We hypothesise that the parent–child dyads managed by providers trained in the higher intensity intervention will demonstrate superiority to dyads managed by providers trained in the lower intensity intervention on the primary outcome of rate of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing, as well as the secondary outcomes of revisits, adverse drug reactions and parent-rated quality of shared decision-making, parent–provider communication and satisfaction.

Methods and analysis

Patient and public involvement

In the early planning stages for this study, we conducted focus groups and individual interviews with clinical, parent, payer and community stakeholders to assess the viability and inform the design of the study. We then recruited a Parent Research Associate who is a core member of our research team, attends all meetings, contributes to all decisions about the study and co-leads our Community Advisory Board (CAB). Our CAB comprises 15 parent, provider and community stakeholders and is diverse (ie, three males, seven Latinx (three exclusively Spanish speaking) and three African-Americans). CAB meetings will occur every other month during year 1 and twice yearly in years 2 and 3. All aspect of the study design, settings, participant burden, materials, procedures, interpretation of data and dissemination of study findings have and will be informed by the CAB and Community Research Associate. Study results will be disseminated to all clinic providers. A parent summary of findings will be developed and provided to study sites who will be encouraged to post in their facilities and/or mail to parents.

Trial design, setting and participants

Trial design

A multisite parallel group, cluster randomised trial with balanced randomisation (1:1) will be performed in three ambulatory paediatric clinics in the USA. Recruitment of providers will start in January of 2017 and continue throughout the study as new providers are hired. Providers (physicians and nurse practitioners) will be randomly assigned to training in either the higher intensity or lower intensity intervention described below. Once providers have been randomised and trained, eligible parent–child dyads will be enrolled and exposed to management by a provider who was trained in one of the interventions. Recruitment of parent–child dyads will start in March of 2017 and continue through December of 2018. Parents in both arms will receive education on the pros and cons of antibiotics for common infections and tips for communicating with their provider. Blinding of providers will not be feasible in this study; however, parents will be blinded as they will not be told what study arm their provider is in, nor informed about differences between the study interventions. Study team members who conduct chart review to code appropriateness of antibiotic prescriptions and code session audiotapes for intervention fidelity will be blinded. A principal investigator (KG) will monitor recruitment, retention (bimonthly) and adverse events (quarterly; blinded to study arm) in this low-risk study. Adverse events will be collected from parents at 2-week follow-up, through chart review and spontaneously from clinic staff. Any protocol modifications will be submitted for Institutional Review Board review and communicated to all relevant parties before implementation.

Randomisation

To protect against practice effects (tendency for providers to have more consistent beliefs and behaviours within their practice compared with providers in other practices), we will randomise providers rather than clinic sites. We did this because the intervention components are not easily transferred between providers making the risk of contamination a much smaller threat to validity than practice effects. As detailed below in the higher intensity provider training section, we will employ several strategies to reduce the chance of contamination across study arms. We will use clinic data on visits among our target population from the past six months to assign each provider to a large or small patient volume group. The study statistician will then stratify the randomisation of providers to ensure each study arm is balanced across large and small volume providers and across clinics. The study statistician will place the intervention group assignment in sealed envelopes labelled with providers’ names. Providers will be given their envelopes at the conclusion of a brief study orientation and informed consent meeting and before completing the baseline assessment.

Setting

Study sites will be an academic medical centre (Children’s Mercy Hospital Primary Care Clinic (CMH PCC)) and both locations of a private practice (Heartland Primary Care (HPC)). CMH PCC sees a racially and ethnically diverse group of patients (41% African-American/black, 29% Hispanic, 18% white) from the Kansas City metropolitan area, of which 73% are covered by Medicaid. CMH PCC has 38 providers (28 paediatricians and 10 nurse practitioners) and treats approximately 2100 children with an ARTI that meet study inclusion criteria yearly. HPC is a community-based private practice with two locations in sub-urban Kansas City serving a diverse patient population (14% African-American/black, 16% Hispanic, 75% white; 42% covered by Medicaid). HPC has nine paediatric providers (six paediatricians and three nurse practitioners) who care for 2000 children that meet study inclusion criteria annually. Approximately 20% of parents at study sites are Spanish speaking.

Participants

This study involves providers and parent–child dyads. We will attempt to recruit all eligible providers at all study sites (paediatricians, paediatric nurse practitioners; n=47), defined as those who regularly treat patients that meet our inclusion criteria. Providers primarily assigned to administration, urgent care or specialty clinics that serve complex care patients will not be eligible. We will conduct brief study orientation and informed consent meetings to enrol providers during regularly scheduled clinic meetings or individual contacts.

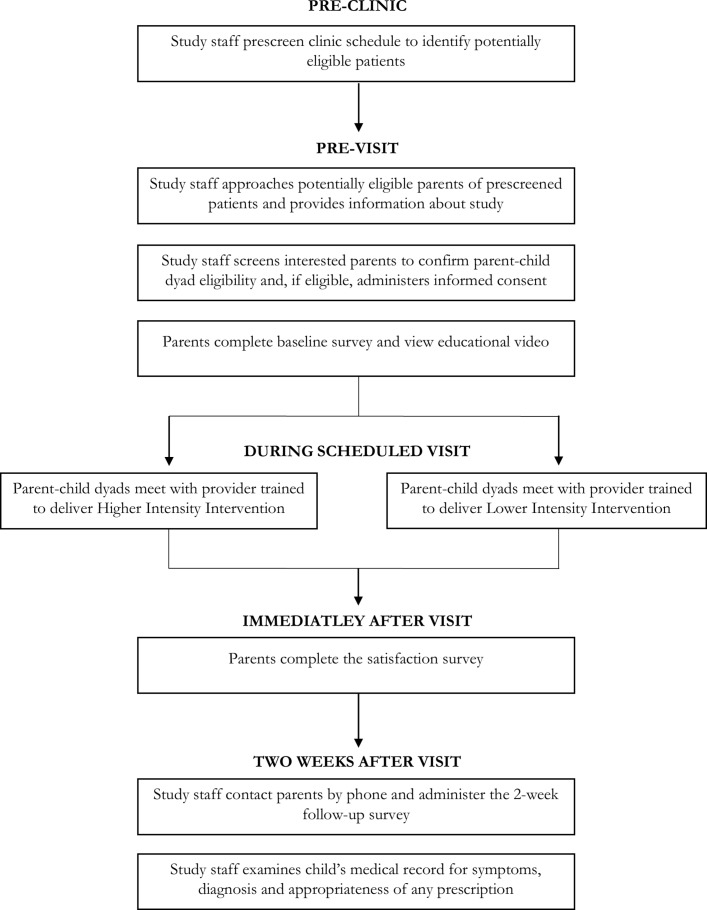

We will recruit up to 1600 parent–child dyads (see figure 1). Dyads will be eligible if the patient is between ages 1 and 5 years (ie, before sixth birthday), presents with ARTI symptoms (eg, cough, congestion, difficulty breathing, sore throat, ear ache) and his/her parent is fluent in English or Spanish. Children will not be eligible if they have received an antibiotic in the last 30 days, have a concurrent probable bacterial infection (eg, urinary tract infection, soft tissue infections), known immunocompromising conditions (eg, HIV, malignancy, solid-organ transplant, chronic corticosteroid use) or factors that make shared decision-making around prescribing an antibiotic extremely complex, like children with complex chronic care conditions (eg, cystic fibrosis),24 or who require hospitalisation during the visit. We will include patients with penicillin allergy as shared decision-making with this group is especially important given more limited treatment options. Parents or children who have previously participated in the study will not be eligible to participate again. Potentially eligible dyads will be identified through prescreening all appointments and parents will be given a study flyer on check-in. Potential eligible dyads will be greeted in the exam room before the provider arrives, given a short synopsis of the study and offered eligibility screening. If more than one caregiver is with the child, they will be asked to designate one person who will complete the informed consent and all assessments. Providers will have no role in identifying potentially eligible dyads, screening, consenting or data collection.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of parent–patient dyad participant flow.

Trial interventions

Higher intensity intervention

With attention to the feasibility in the US healthcare system, this intervention will be informed by a series of evidence-based interventions conducted in the UK and Europe: Enhancing the Quality of Information-sharing in Primary care (EQUIP),23 25 Improving the Management of Patients with Acute Cough Trial (IMPACT),26 27Stemming the Tide of Antibiotic Resistance (STAR)28 29 and Genomics to combat Resistance against Antibiotics in Community-acquired LRTI in Europe (GRACE).30

Higher intensity arm provider training

Providers in this arm will receive two trainings. First, a 20 min, in-person general education training provided by a study physician (ALM, JGN) will cover the pros and cons of antibiotics, the impact of inappropriate use, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention antibiotic prescribing guidelines, common reasons for antibiotic misuse and viewing/discussing of the parent educational cartoon (described below). Didactic and interactive learning strategies will be employed to review the appropriate diagnostic criteria to help distinguish a viral ARTI from a bacterial ARTI, as well as the recommended narrow spectrum antibiotic for bacterial ARTI. Second, providers will receive a 50 min, in-person training on parent-centred communication skills provided by a behavioural psychologist (KG). The training will use a variety of educational strategies including viewing/discussing of motivational and role model videos, lecture and group discussion. The goal is to enhance providers’ confidence in use of parent-centred communication strategies (eg, open-ended questions, affirming and elicit–provide–elicit) and the study trifold brochure to conduct key aspects of the EQUIP/IMPACT/STAR/GRACE interventions during consultations. Specifically, they will learn to (1) elicit parents’ expectations, (2) affirm parents’ concerns, (3) provide an evidence-based estimate of likely illness duration, (4) provide gain-framed antibiotic information, (5) recommend options for symptom relief, (6) identify triggers for reconsult and contingency plans and (7) elicit parents’ thoughts on the plan. Providers will also learn to use the study trifold brochure to ensure that they complete all necessary aspects of the intervention and provide written notes for parents to refer to after the visit. The inside of the study trifold brochure provides gain-framed information about when antibiotics are and are not necessary and what risks are involved in taking antibiotics. Research has shown that people react to the same trade-off in different ways depending on whether the possible outcomes are presented as losses or gains.31 In this study, we will train providers and tailor our parent materials to highlight the gains of not using antibiotics (eg, staying safe from side effects, making sure that effective cures are available in the future, knowing that their child’s body will fight off most ARTI on its own) that may increase parents’ comfort with not getting an antibiotic prescription for their child. Drawing from the EQUIP study,25 the outside of the brochure includes a place to write the child’s first name; check boxes to indicate the diagnosis, recommended home care treatments and reasons for reconsultation; expected recovery time, if antibiotics are needed, and tips for communicating with providers.

To reduce their reliance on guessing what parents want, providers will also be trained to rely on parents’ antibiotic desire ratings taken from their baseline survey and provided at the start of each visit via a sticky note on the exam room door where parent–child dyads will be waiting. To assess fidelity to the communication skills, we will audio record a subsample of visits (10%) in both higher and lower intensity arms and objectively code use of key communication strategies using established methods that we have successfully employed in other studies.32 33 We will deliver in-person provider training as studies have shown the value of an active approach over more passive web-based versions,34 but we will also develop web-based refresher trainings.

Higher intensity arm parent training

In exam rooms prior to the consultation, parents will complete the baseline survey, view a 90 s educational cartoon video with accompanying educational trifold brochure and rate their desire for antibiotics via a tablet computer. The educational video uses gain-framed messages31 35 to explain when antibiotics are and are not indicated while emphasising the risk of side effects and the creation of resistant organisms. It also highlights what information should be provided during the consultation (eg, an estimate of illness duration, recommendations for system relief and triggers for reconsult and contingency plans). Parents in this arm will receive a hard copy of the study trifold brochure.

Lower intensity intervention

This intervention will be modelled on proven parent-focused and provider-focused educational interventions used in previous studies.19 34 36–44 Providers will complete the same 20 min, in-person general education training described above. Parents will receive the same parent training described above except that parents will not receive a hard copy of the study trifold brochure and their antibiotic desire ratings will not be shared with providers.

Several measures will be taken to reduce the likelihood of contamination between arms. Specifically, we will (1) train study team members to ensure that all of our communications (written or in person) with providers in the lower intensity arm do not reveal any of the strategies from the higher intensity training, (2) review the importance of keeping intervention arms distinct in randomised controlled trial designs during training, (3) directly ask providers to pledge not to share any details of the additional communication skills training with their colleagues randomised to the lower intensity arm, (4) control the dissemination of the trifold brochure to ensure that only parents who are consulted by providers in the higher intensity arm receive them and (5) offer communication strategies for dealing with colleagues who ask for more information.

Data collection

Providers/administrators

At baseline, providers will complete a brief survey collecting demographic data and providers’ views on parent interest in antibiotics for viral illness, their comfort with telling parents that antibiotics are not necessary and their concern about parents’ responses. Once parent–child dyad recruitment is complete, a brief survey mirroring the baseline provider assessment and a brief (<10 min) semistructured individual interview will be conducted with providers and administrators to learn about their experience of being in the study, suggestions for improvement and ideas about disseminating to other settings. Providers/administrators will not receive incentives for study participation.

Parents

At baseline, immediately before their scheduled visit with a provider, parents will complete a brief tablet computer-administered Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) survey about their antibiotic knowledge and interest in antibiotics for their child’s current condition. They will then view the educational video and indicate their interest in antibiotics for their child’s current condition again and rate the likelihood of actually receiving antibiotics during their visit. After meeting with their provider, parents will complete a brief survey about their experience of the visit including their rating of shared decision-making, satisfaction with parent–provider communication and overall satisfaction with the visit. Two weeks later, parents will be contacted via phone to complete a follow-up survey to assess resolution of child’s illness, any additional healthcare visits and/or treatment, if contingency or ‘back-up’ prescriptions were filled, presence and severity of side effects from any antibiotics administered, use of home care treatment suggested by provider, assessment of the educational video and brochure, and satisfaction with study participation. Electronic medical record (EMR) data will be abstracted using a standardised data collection form and evaluated by study physicians to determine the appropriateness of antibiotic prescribing. Parents will be provided with $10 per completed survey in recognition of their time and effort.

Measures

Interest in assessing patient/parent–provider communication has garnered significant attention, but measurement challenges remain. Despite a large number of published instruments, availability of valid, reliable and scalable measures is a recognised barrier to progress in research and implementation of patient-centred care.45 Lack of patient involvement in scale development has been cited as a contributing factor, so we have engaged parent and provider stakeholders in the selection of measures for this study. All measures have been adapted based on their feedback, pilot testing including cognitive debriefing was performed to ensure the briefest possible assessment of study outcomes. All measures were translated into Spanish using standard methods and appropriate pilot testing.

Primary outcome

Antibiotic prescribing

Our primary research question is which of the two interventions leads to a lower rate of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing. We hypothesise that the rate among providers in the higher intensity arm will be lower than the rate produced by providers in the lower intensity arm. If the rates do not significantly differ, we will recommend the lower intensity intervention as preferable for dissemination as its implementation requires less time and resources. Inappropriate prescribing will be assessed on a weekly basis by study physicians, blinded to study arm, who will review the medical record documentation for each enrolled patient’s visit to determine if inappropriate antibiotic prescribing occurred. Prescriptions will be considered inappropriate if they meet any of the following criteria: (1) antibiotic prescribed for a viral ARTI, (2) antibiotic prescribed for a presumed bacterial ARTI that does not meet table 1 criteria, (3) broad-spectrum antibiotic prescribed for a bacterial ARTI in a child without a penicillin allergy or (4) non-recommended alternative antibiotic prescribed for a bacterial ARTI (see table 2) in a child with a penicillin allergy.

Table 1.

Diagnostic criteria for acute respiratory tract infections (ARTIs)19 34 36 46 51

| Bacterial ARTI | Diagnostic criteria |

| Acute otitis media (either criteria) |

|

| Sinusitis (any of the three criteria) |

|

| Community-acquired pneumonia (either criteria) |

|

| Streptococcal pharyngitis (both criteria) |

|

Table 2.

Appropriate antibiotic selection19 36 46 51

| Bacterial acute respiratory tract infection | Primary antibiotic | Secondary antibiotics for penicillin allergy |

| Acute otitis media | Amoxicillin | Cefdinir, cefpodoxime, ceftriaxone, cefuroxime, clindamycin |

| Community-acquired Pneumonia | Amoxicillin | Cefpodoxime, cefprozil, cefuroxime, clindamycin |

| Sinusitis | Amoxicillin | Cefdinir, cefpodoxime, cefuroxime, clindamycin |

| Streptococcal pharyngitis | Amoxicillin | Cephalexin (preferred unless previous type I hypersensitivity reaction to penicillin) clindamycin, azithromycin |

Instead of relying on diagnostic codes as has been done in previous studies,46 47 the study physicians will assess the appropriateness of the patient’s diagnosis by reviewing detailed symptoms, physical examination findings and diagnostic tests in the EMR. This will guard against the potential bias of relying on diagnostic codes alone as clinicians sometimes match diagnostic codes to support their antibiotic prescribing.12 Children determined to have a bacterial infection will need documentation of the specific diagnoses and the clinical criteria confirming that diagnosis (listed in table 1). Ten per cent of all chart reviews will be verified by the other study physician blinded to the initial coding and study group. Overall antibiotic prescription rate for different ARTI diagnoses by arm will also be reported.

Secondary outcomes

Revisits and adverse drug reactions

We will determine if children seen by providers in the two study arms differ in terms of revisits and/or adverse drug reactions. Data on these clinical outcomes will be collected via follow-up phone calls with parents conducted 2 weeks after the visit. Parents will be asked if any additional healthcare visits and/or treatment occurred and, if antibiotics were given to the child, if any side effects or adverse drug reactions occurred. Parents will also be asked to report on when their child’s symptoms improved, if contingency prescriptions were filled, use of home care treatment suggested by the provider, assessment of the educational video and brochure, and satisfaction with study participation.

Shared decision-making

We will assess parent ratings of shared decision-making using an adapted version of the three-item CollaboRATE questionnaire.48 This very brief (<30 s) scale was developed with input of end users and assesses the ‘effort’ that providers put forward to initiate shared decision-making. Members of our community advisory board and participants in several studies have strongly preferred the CollaboRATE scale to other measures of shared decision-making, especially for more routine healthcare issues.49 Items are: ‘How much effort was made to … (1) help you understand your child’s health issue?; (2) listen to the things that matter most to you about your child’s health issues?; and (3) include what matters most to you in choosing what to do next?’ Items are scored on a 10-point response scale ranging from 0 ‘no effort was made’ to 9 ‘every effort was made.’ In a simulation study, the CollaboRATE scale demonstrated discriminative validity between six standardised patient–provider encounters that included varied amounts of shared decision-making, concurrent validity with other measures of shared decision makingDM, excellent test–retest reliability and sensitivity to change.50

Quality of parent–provider communication

We will use a single item: ‘How satisfied were you with the communication between you and your child’s healthcare provider?’ with a five-point Likert-type response format ranging from ‘very dissatisfied’ to ‘very satisfied’.

Overall satisfaction with the visit

We will use a single item: ‘Overall, how satisfied were you with the visit?’ with a five-point Likert-type response format ranging from ‘very dissatisfied’ to ‘very satisfied’.

Data analyses

Power and sample size

Prior research examining our primary outcome has shown that 30% of the antibiotics prescribed in the outpatient ARTI visits are inappropriate.5 Prior behavioural intervention studies have produced 20%–81% reductions in inappropriate prescribing,46 51 with statistically significant differences between intervention and control arms (effect sizes: 8.3%46 and 13.1%).51 Based on the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) observed in the Meeker et al study which is most similar to our study, we assume an ICC of .04. Assuming 30% inappropriate prescribing at baseline and a 20% decrease in the lower intensity arm and a conservative 50% decrease in the higher intensity arm following intervention, with 40 providers (clusters), α of .05 and 80% power, we will need a sample size of 760 per arm to detect a 9% difference between arms (inappropriate antibiotic 24% in the lower intensity arm vs 15% in the higher intensity arm after intervention). Consistent with our historical retention rates in similar studies in the same setting, we will protect against an attrition rate of 5% and aim to recruit 1600 participants to ensure adequate power to assess our primary outcome and secondary outcomes.

Planned analytic strategy

All analyses will be conducted using an intent-to-treat strategy with available data. Initial analyses will examine the underlying distributions of the primary and secondary outcomes. ‘Ceiling effects’ on these measures of parent satisfaction are not uncommon and depending on the level of skewness, we may elect to dichotomise specific scales. We will construct an analytic model to assess the impact of intervention type on our primary outcome of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing. This is a two-stage nested design, with parents nested within providers (level 1 units) and study site (level 2 units). Consequently, ordinary least squares and logistic regression models are not appropriate since the data violate the independently and identically distributed assumption. We will use generalised linear mixed-effect regression models using Stata52 which allow for easy specification of both fixed and random effects, including accommodating ≥1 cluster variables. Alternative covariance structures will be investigated; though we hypothesise the exchangeable (or compound symmetry) structure will suffice. We will employ robust SEs to help minimise misspecification and examine time as a potential random effect. The data will be analysed using a post-test-only approach. Next, we will examine the effects of the potential covariates (eg, parent’s/patient’s gender, insurance type, parent’s self-reported race and ethnicity, parent’s educational attainment and provider’s years of clinical experience) on the primary and secondary outcomes. Our goal is to identify parsimonious final models with the fewest covariates that best describe the outcomes.

Additionally, we will explore the heterogeneity of treatment effect or the possibility that one or both of the interventions work better for specific groups. Variables for consideration include language spoken at home, language the visit was conducted in and age of child. We will create a binary indicator for each variable and include each as an interaction term in the regression models. We will examine these interaction terms across intervention arms and explore within-arm differential trends in our primary and secondary outcomes over time.

Missing data

All analyses will be conducted with available data. We do not anticipate important amounts of missing data as all data for primary outcomes are collected in a single visit before incentives are offered and we will require responses in the REDCap form.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval was obtained from the Children’s Mercy Hospital Pediatric Institutional Review Board (#16060466). All participants will provide written informed consent prior to participating in the study. We will employ multiple strategies to protect confidentiality of personal information about potential and enrolled participants. Prescreening of patients will be conducted exclusively by trained study staff on password-protected computers and REDCap data collection tool. Appointments with potential participants will be flagged in electronic clinic scheduling systems accessible only to clinic and study staff. Enrolled parent and patient participants will complete all measures in REDCap projects, which will only be accessible to study staff who must use multiple passwords to access REDCap through the Children’s Mercy network. Personal identifying information, namely medical record number and contact information, is marked as an identifier in REDCap and is then censored when the database is downloaded for analysis. All identifying information will be removed with the deletion of the REDCap project at the end of the study. Audio files of clinic visits will be stored in a password-protected file on the Children’s Mercy server that is only accessible to members of the study staff. Consent forms and signature logs for reimbursements will be secured in a locked file cabinet within a locked office on a secured floor.

A full data package will be maintained by the investigators at Children’s Mercy Hospital for at least 7 years after data collection is complete. Third-party access to the full data package will be addressed by Children’s Mercy Hospital on a case-by-case basis.

Results will be disseminated through publication in peer-reviewed journals and conference presentations. Study progress and findings will also be updated on clinicaltrials.gov (#NCT03037112).

Discussion

Effective parent–provider communication facilitates rapport-building, exchange of critical information and shared decision-making which ultimately has the potential to reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing and use. Nevertheless, efficacious and feasible training interventions that enhance effective parent–provider communication, shared decision-making and antibiotic prescribing are lacking. This study will be the first to compare the efficacy of two interventions directly targeting parent–provider communication about antibiotics in the US outpatient paediatric setting. It will also provide novel insights about parental expectations for antibiotics following the receipt of gain-framed information and providers’ experience of the interventions. If successful, the superior intervention could be widely disseminated and potentially lead to reduced healthcare costs through more appropriate antibiotic use, decreased additional visits by parents who may not have felt satisfied with their initial visit and ultimately less antibiotic resistance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions made by our Parent Research Associate (Carey Bickford), parent stakeholders on our Community Advisory Board and clinical stakeholders at Children’s Mercy Primary Care Clinics and Heartland Clinics in designing this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors made substantial contributions to the design of the study. KG, AB-E, ALM, BRL, EAH and JGN contributed to drafting the protocol and revising it critically for important intellectual content. KBD, SS, AR, KP, DY, KW, SL and CCB contributed critical revisions to the draft for important intellectual content. All authors reviewed and approved of the final version submitted for publication and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuing that questions related to accuracy and integrity are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Program Award (CDR-1507-31759).

Disclaimer: All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study protocol is in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration and was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Children’s Mercy Hospital (#16060466).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: This is a study protocol in the pre-results phase with no available data to be shared. After results are obtained, a full data package will be maintained by the investigators at Children’s Mercy Hospital for at least 7 years after data collection is complete. Third-party access to the full data package will be addressed by Children’s Mercy Hospital on a case-by-case basis.

References

- 1. O’Neill J. Antimicrobial resistance : tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations. Rev Antimicrob Resist 2014:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States 2013. Atlanta, 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/ [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shehab N, Patel PR, Srinivasan A, et al. Emergency department visits for antibiotic-associated adverse events. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47:735–43. 10.1086/591126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, Pavia AT, et al. Antibiotic prescribing in ambulatory pediatrics in the United States. Pediatrics 2011;128:1053–61. 10.1542/peds.2011-1337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kronman MP, Zhou C, Mangione-Smith R. Bacterial prevalence and antimicrobial prescribing trends for acute respiratory tract infections. Pediatrics 2014;134:e956–65. 10.1542/peds.2014-0605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nyquist AC, Gonzales R, Steiner JF, et al. Antibiotic prescribing for children with colds, upper respiratory tract infections, and bronchitis. JAMA 1998;279:875–7. 10.1001/jama.279.11.875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vaz LE, Kleinman KP, Raebel MA, et al. Recent trends in outpatient antibiotic use in children. Pediatrics 2014;133:375–85. 10.1542/peds.2013-2903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Finkelstein JA, Dutta-Linn M, Meyer R, et al. Childhood infections, antibiotics, and resistance: what are parents saying now? Clin Pediatr 2014;53:145–50. 10.1177/0009922813505902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Havens L, Schwartz M. Identification of parents’ perceptions of antibiotic use for individualized community education. Glob Pediatr Health 2016;3 10.1177/2333794X16654067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cabral C, Horwood J, Hay AD, et al. How communication affects prescription decisions in consultations for acute illness in children: a systematic review and meta-ethnography. BMC Fam Pract 2014;15:63 10.1186/1471-2296-15-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cabral C, Ingram J, Lucas PJ, et al. Influence of clinical communication on parents' antibiotic expectations for children with respiratory tract infections. Ann Fam Med 2016;14:141–7. 10.1370/afm.1892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Szymczak JE, Feemster KA, Zaoutis TE, et al. Pediatrician perceptions of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2014;35(Suppl 3):S69–78. 10.1086/677826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tonkin-Crine S, Yardley L, Little P. Antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory tract infections in primary care: a systematic review and meta-ethnography. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011;66:2215–23. 10.1093/jac/dkr279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cho HJ, Hong SJ, Park S. Knowledge and beliefs of primary care physicians, pharmacists, and parents on antibiotic use for the pediatric common cold. Soc Sci Med 2004;58:623–9. 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00231-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vinson DC, Lutz LJ. The effect of parental expectations on treatment of children with a cough: a report from ASPN. J Fam Pract 1993;37:23–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mangione-Smith R, McGlynn EA, Elliott MN, et al. The relationship between perceived parental expectations and pediatrician antimicrobial prescribing behavior. Pediatrics 1999;103:711–8. 10.1542/peds.103.4.711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mangione-Smith R, McGlynn EA, Elliott MN, et al. Parent expectations for antibiotics, physician-parent communication, and satisfaction. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2001;155:800–6. 10.1001/archpedi.155.7.800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mangione-Smith R, Zhou C, Robinson JD, et al. Communication practices and antibiotic use for acute respiratory tract infections in children. Ann Fam Med 2015;13:221–7. 10.1370/afm.1785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Andrews T, Thompson M, Buckley DI, et al. Interventions to influence consulting and antibiotic use for acute respiratory tract infections in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2012;7:e30334 10.1371/journal.pone.0030334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hu Y, Walley J, Chou R, et al. Interventions to reduce childhood antibiotic prescribing for upper respiratory infections: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health 2016:1162–70. 10.1136/jech-2015-206543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Francis NA, Phillips R, Wood F, et al. Parents' and clinicians' views of an interactive booklet about respiratory tract infections in children: a qualitative process evaluation of the EQUIP randomised controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract 2013;14:182 10.1186/1471-2296-14-182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grijalva CG, Nuorti JP, Griffin MR. Antibiotic prescription rates for acute respiratory tract infections in US ambulatory settings. JAMA 2009;302:758 10.1001/jama.2009.1163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Francis NA, Butler CC, Hood K, et al. Effect of using an interactive booklet about childhood respiratory tract infections in primary care consultations on reconsulting and antibiotic prescribing: a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2009;339:b2885 10.1136/bmj.b2885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, et al. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr 2014;14:199 10.1186/1471-2431-14-199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Francis NA, Hood K, Simpson S, et al. The effect of using an interactive booklet on childhood respiratory tract infections in consultations: study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial in primary care. BMC Fam Pract 2008;9:23 10.1186/1471-2296-9-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cals JW, Scheppers NA, Hopstaken RM, et al. Evidence based management of acute bronchitis; sustained competence of enhanced communication skills acquisition in general practice. Patient Educ Couns 2007;68:270–8. 10.1016/j.pec.2007.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cals JW, Butler CC, Hopstaken RM, et al. Effect of point of care testing for C reactive protein and training in communication skills on antibiotic use in lower respiratory tract infections: cluster randomised trial. BMJ 2009;338:b1374 10.1136/bmj.b1374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Butler CC, Simpson SA, Dunstan F, et al. Effectiveness of multifaceted educational programme to reduce antibiotic dispensing in primary care: practice based randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2012;344:d8173 10.1136/bmj.d8173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bekkers MJ, Simpson SA, Dunstan F, et al. Enhancing the quality of antibiotic prescribing in primary care: qualitative evaluation of a blended learning intervention. BMC Fam Pract 2010;11:34 10.1186/1471-2296-11-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Little P, Stuart B, Francis N, et al. Effects of internet-based training on antibiotic prescribing rates for acute respiratory-tract infections: a multinational, cluster, randomised, factorial, controlled trial. Lancet 2013;382:1175–82. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60994-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Matjasko JL, Cawley JH, Baker-Goering MM, et al. Applying Behavioral Economics to Public Health Policy: Illustrative Examples and Promising Directions. Am J Prev Med 2016;50:S13–9. 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Catley D, Harris KJ, Goggin K, et al. Motivational Interviewing for encouraging quit attempts among unmotivated smokers: study protocol of a randomized, controlled, efficacy trial. BMC Public Health 2012;12:456 10.1186/1471-2458-12-456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goggin K, Gerkovich MM, Williams KB, et al. A randomized controlled trial examining the efficacy of motivational counseling with observed therapy for antiretroviral therapy adherence. AIDS Behav 2013;17:1992–2001. 10.1007/s10461-013-0467-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ranji SR, Steinman MA, Shojania KG, et al. Interventions to reduce unnecessary antibiotic prescribing: a systematic review and quantitative analysis. Med Care 2008;46:847–62. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318178eabd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bartels RD, Kelly KM, Rothman AJ. Moving beyond the function of the health behaviour: the effect of message frame on behavioural decision-making. Psychol Health 2010;25:821–38. 10.1080/08870440902893708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. van der Velden AW, Pijpers EJ, Kuyvenhoven MM, et al. Effectiveness of physician-targeted interventions to improve antibiotic use for respiratory tract infections. Br J Gen Pract 2012;62:801–7. 10.3399/bjgp12X659268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Maor Y, Raz M, Rubinstein E, et al. Changing parents' opinions regarding antibiotic use in primary care. Eur J Pediatr 2011;170:359–64. 10.1007/s00431-010-1301-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schnellinger M, Finkelstein M, Thygeson MV, et al. Animated video vs pamphlet: comparing the success of educating parents about proper antibiotic use. Pediatrics 2010;125:990–6. 10.1542/peds.2009-2916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Taylor JA, Kwan-Gett TS, McMahon EM. Effectiveness of a parental educational intervention in reducing antibiotic use in children: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2005;24:489–93. 10.1097/01.inf.0000164706.91337.5d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. González Ochoa E, Armas Pérez L, Bravo González JR, et al. Prescription of antibiotics for mild acute respiratory infections in children. Bull Pan Am Health Organ 1996;30:106–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hennessy TW, Petersen KM, Bruden D, et al. Changes in antibiotic-prescribing practices and carriage of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae: A controlled intervention trial in rural Alaska. Clin Infect Dis 2002;34:1543–50. 10.1086/340534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hingorani R, Mahmood M, Alweis R. Improving antibiotic adherence in treatment of acute upper respiratory infections: a quality improvement process. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect 2015;5:27472 10.3402/jchimp.v5.27472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Juzych NS, Banerjee M, Essenmacher L, et al. Improvements in antimicrobial prescribing for treatment of upper respiratory tract infections through provider education. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:901–5. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0198.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Smeets HM, De Wit NJ, Delnoij DM, et al. Patient attitudes towards and experiences with an intervention programme to reduce chronic acid-suppressing drug intake in primary care. Eur J Gen Pract 2009;15:219–25. 10.3109/13814780903452168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Scholl I, Koelewijn-van Loon M, Sepucha K, et al. Measurement of shared decision making - a review of instruments. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes 2011;105:313–24. 10.1016/j.zefq.2011.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Fiks AG, et al. Effect of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention on broad-spectrum antibiotic prescribing by primary care pediatricians: a randomized trial. JAMA 2013;309:2345 10.1001/jama.2013.6287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Finkelstein JA, Davis RL, Dowell SF, et al. Reducing antibiotic use in children: a randomized trial in 12 practices. Pediatrics 2001;108:1–7. 10.1542/peds.108.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Elwyn G, Barr PJ, Grande SW, et al. Developing CollaboRATE: a fast and frugal patient-reported measure of shared decision making in clinical encounters. Patient Educ Couns 2013;93:102–7. 10.1016/j.pec.2013.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Barr PJ, Elwyn G. Measurement challenges in shared decision making: putting the ’patient' in patient-reported measures. Health Expect 2016;19:993–1001. 10.1111/hex.12380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Barr PJ, Thompson R, Walsh T, et al. The psychometric properties of CollaboRATE: a fast and frugal patient-reported measure of the shared decision-making process. J Med Internet Res 2014;16:e2–19. 10.2196/jmir.3085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Meeker D, Linder JA, Fox CR, et al. Effect of behavioral interventions on inappropriate antibiotic prescribing among primary care practices: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016;315:562–70. 10.1001/jama.2016.0275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. StataCorp. Stata statistical software: release 14. 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.