Abstract

Objective

Sedentary behaviour has long been associated with neck and low back pain, although relatively little is known about the thoracic spine. Contributing around 33% of functional neck movement, understanding the effect of sedentary behaviour and physical activity on thoracic spinal mobility may guide clinical practice and inform research of novel interventions.

Design

An assessor-blinded prospective observational study designed and reported in accordance with Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology.

Setting

UK university (June–September 2016).

Participants

A convenience sample (18–30 years) was recruited and based on self-report behaviours, the participants were assigned to one of three groups: group 1, sitters—sitting >7 hours/day+physical activity<150 min/week; group 2, physically active—moderate exercise >150 min/week+sitting <4 hours/day and group 3, low activity—sitting 2–7 hours/day+physical activity <150 min/week.

Outcome measures

Thoracic spine mobility was assessed in the heel-sit position using Acumar digital goniometer; a validated measure. Descriptive and inferential analyses included analysis of variance and analysis of covariance for between group differences and Spearman’s rank correlation for post hoc analysis of associations.

Results

The sample (n=92) comprised: sitters n=30, physically active n=32 and low activity n=30. Groups were comparable with respect to age and body mass index.

Thoracic spine mobility (mean (SD)) was: group 1 sitters 64.75 (1.20), group 2 physically active 74.96 (1.18) and group 3 low activity 68.44 (1.22). Significant differences were detected between (1) sitters and low activity, (2) sitters and physically active (p<0.001). There was an overall effect size of 0.31. Correlations between thoracic rotation and exercise duration (r=0.67, p<0.001), sitting duration (r=−0.29, p<0.001) and days exercised (r=0.45, p<0.001) were observed.

Conclusions

Findings evidence reduced thoracic mobility in individuals who spend >7 hours/day sitting and <150 min/week of physical activity. Further research is required to explore possible causal relationships between activity behaviours and spinal musculoskeletal health.

Keywords: sedentary behaviour, physical activity, thoracic spine, spinal mobility, spinal pain

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study employed rigorous methods and validated approaches to investigate thoracic spine mobility.

The inclusion of accelerometry would have been useful to verify self-report behaviours.

While the study sample size was based on a priori power calculation of the primary outcome, a validated measure of thoracic spine mobility, individual group sample size was insufficient to support further post hoc analysis.

Introduction

Background/rationale

Sedentary lifestyles are an undesirable hallmark of modern society, affecting a significant proportion of the population.1 Prolonged sitting (a form of sedentary behaviour) has progressively become the norm with computerisation in the work place, transportation modernisation and advances in domestic technology.2 These developments are not only detrimental for physiological health and well-being with rising levels of obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease,3 but also musculoskeletal health and well-being, with recent research finding an association between prolonged sitting (>8 hours a day) and increased neck–shoulder4–7 and low back pain.8 It is therefore reasonable to suppose that sedentary behaviours may induce musculoskeletal changes within the relatively stiff thoracic spine; contributing towards the dysfunction in the adjacent spinal regions. The term ‘regional interdependence’ describes a relationship whereby seemingly unrelated impairments in one anatomical region are associated with the development or persistence of pain in another.9 Contributing to 33% and 21% of the movement occurring during neck flexion and rotation respectively,10 it is not surprising that the thoracic spine may contribute to the development of pain surrounding the neck. Empirical evidence supports this theory, where thoracic spine or movement dysfunction has been linked to pathologies in the neck11 shoulder12 and elbow.13 Furthermore, there is a considerable body of compelling evidence to support the use of physiotherapy treatment techniques targeting the thoracic spine in clinical presentations of neck and shoulder pain.14–16 Notwithstanding the paucity of literature exploring the influence of sedentary behaviours on the thoracic spine, one large cross-sectional study (n=1886) did report a relatively high prevalence of thoracic spine pain, alongside neck and back pain in sedentary workers (36%–41%), most notably in individuals with postural constraints, such as drivers and individuals unable to change tasks regularly.17 However, the relationship between sedentary behaviour and thoracic mobility, a proxy for spinal musculoskeletal health, contributing 80% of axial spinal trunk rotation18 has not yet been established.

Arguably, those who are physically active may present with greater mobility of their thoracic region where exercise promotes joint and soft tissue mobility, countering the deleterious adaptive shortening of muscles and joint stiffness through static postures.19 However, it remains unclear what physical activity is comprised of in terms of ‘length of activity’, ‘type of activity’ and ‘how often’ the activity is performed. Physical activity has been previously defined as ‘more than 150 min of moderate to intense physical activity per week’.20 However, a focus on physical exertion seems inadequate when considering musculoskeletal health,21 and arguably biomechanical factors such as mobility and types of activity should also be considered, where some physical activities have been subclassified as linear (straight line, eg, running) or dynamic (rotational, eg, tennis) in nature.

With sedentary lifestyles becoming increasingly the norm and evidence that sitting for just 1 hour leads to increased spinal stiffness,22 it is now important to further investigate the relationship between sedentary behaviours, physical activity and thoracic spine mobility. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the influence of prolonged sitting and physical activity on thoracic spine mobility.

Objectives

Investigate the influence of sedentary behaviour on thoracic spine mobility.

Investigate the influence of physical activity on thoracic spine mobility.

To evaluate whether a relationship exists between duration of sitting and physical activity and thoracic mobility.

Methods

Design and setting

A single assessor-blinded prospective observational study was conducted between April and June 2016 within a University setting; designed and reported in line with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.23

Recruitment

Participants were recruited via email from the staff and student body of a large UK university using posters and email advertisement. Interested and eligible participants were provided with a participant information sheet, had their questions answered and were asked to provide written informed consent. Screening against eligibility criteria was performed at the point of recruitment by a research assistant (KT).

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki with participants able to withdraw at any point.

Participants

Participants comprised a convenience sample of healthy asymptomatic volunteers from within a UK university population. Eligibility criteria included young adults aged 18–30 years who fulfilled one of the following criteria based on Dunstan et al,24 for sitting duration and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Guidelines25 for duration of moderate-intensity physical activity.26 The sample size was based on a minimum of 30 per group to be able to detect a minimum clinically important difference (10°) in thoracic spinal rotation movement between the groups, based on power 0.8 and at 5% significance level.27

Individuals who participate in >150 min of physical activity per week and sit <4 hours per day (physically active).

Individuals who participate in <150 min of physical activity per week and sit >7 hours per day (sitters).

Individuals who spend between 4 and 7 hours of sitting daily and <150 min of physical activity per week (low activity).

Exclusion criteria included a current or previous neuromusculoskeletal spine condition, rheumatoid arthritis, current or chronic respiratory condition, pregnancy, current hip or knee pathology, unable to adopt heel-sit position, not fulfilling one of the criteria listed above.

Variables: demographic data and outcome assessment

Procedure

Piloting to determine the feasibility of the protocol was performed prior to the main study. For the main study, one researcher (KT) recruited, screened and took all baseline measures to characterise the sample [age, gender, body mass index (BMI), exercise type/duration, sitting duration]. The primary measure of interest, thoracic spine mobility, was recorded by a blinded assessor (GB) with the participant an a heel-sit position.28 29 Following familiarisation and three practice attempts from a position of full right to left rotation to ensure stability of measures,27 the end range position of the fourth rotation was measured three times using an Acumar digital inclinometer placed over the C7–T1 interspinous space.27 29 The mean of the three measures for full right and left rotations were recorded and retained for data analysis.27

Outcome measure

The Acumar digital inclinometer (Acumar, Model ACU 360, Lafayette Instrument Company, Indiana, USA) was used to measure thoracic spine rotation. The heel-sit position was chosen to minimise concurrent movement occurring in the relatively mobile lumbar spine, a limitation of sitting where rotation comprises motion from both regions.28 Reliability (ICC 2,1 (95% CI), 0.88 (0.78, 0.93)), and strong criterion (r=0.88) and concurrent validity (r=0.98) against a combined imaging and motion analysis approach have previously been established.28 29

Bias

A number of measures were put in place to minimise the influence of bias, including use of a validated measurement approach,29 standardisation of procedures through training of assessor, assessor blinding, controlling for environmental variables, avoidance of physical activity prior to testing, partial blinding of participants in that they were not made aware of a priori planned comparison between groups and piloting of all procedures in advance of the main study.

Statistical methods

Data were transferred to SPSS V.22 (IBM) and checked to ensure their integrity by two researchers. Descriptive statistical analyses included a summary of participant characteristics (age, gender, BMI, types of exercise, duration of exercise and sitting) using means, SD. Inferential analysis initially included one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to explore between-group differences and post hoc comparisons to explore between-group differences. Effect size (eta squared) was calculated and interpreted using Cohen’s classification.30

Further inferential analyses included an analysis of co-variance (ANCOVA) to determine main effects including Bonferroni correction (with pairwise comparisons) to evaluate between-group differences in thoracic spine mobility with gender as a covariate (as groups were imbalanced with respect to gender). Spearman’s rank correlation correlational analyses were used to evaluate the relationships between thoracic mobility and self-report measures of sitting duration, days active and physical activity. For all analyses, statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Patient involvement

The study was conceived from our working with patients with spinal complaints over many years and their views were used to inform the design and methods used. Study findings have been disseminated to patients and participants via conference presentations including the Centre of Precision Rehabilitation for Spinal Pain, Patient and Public Involvement Group.

Results

Participants, descriptive data and outcome data

A total of 92 participants were recruited. Baseline characteristics, self-reported behaviours for physical activity (exercise duration and types of exercise) and sitting duration are presented in table 1. Groups were comparable with respect to age and BMI (p>0.05), but not for gender with more women were recruited to the low activity and sitter group.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Sitters, n=30 | Physically active, n=32 | Low activity, n=30 | |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 22.73 (2.92) | 22.03 (2.65) | 20.93 (2.49) |

| Gender (women %) | 63.3* | 47.0* | 76.7* |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 22.90 (2.47) | 23.12 (2.92) | 22.60 (2.36) |

| Thoracic rotation degrees, mean (SD) | 64.74 (8.93) | 74.96 (8.26) | 68.44 (4.36) |

| 95% CI | 62.37 to 67.14 | 72.61 to 77.31 | 66.02 to 70.86 |

| Exercise duration (minutes) | |||

| 0–30 | 7 | – | 3 |

| 30 –60 | 4 | – | 6 |

| 60 – 90 | 15 | – | 5 |

| 90 – 150 | 4 | – | 16 |

| 150 – 180 | – | 4 | – |

| 180 – 210 | – | 12 | – |

| 210 – 240 | – | 5 | – |

| 240+ | – | 11 | – |

| Types of exercise (frequency) | |||

| Gym cardio | 6 | 10 | 1 |

| Gym weights | 5 | 3 | 9 |

| Running | 10 | 6 | – |

| Cycling | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| Dance/gymnastics | – | 3 | 1 |

| Football | – | 4 | 2 |

| Netball/basketball | – | 1 | 1 |

| Tennis | – | 3 | 2 |

| Rowing | – | 1 | – |

| Martial arts | 1 | – | – |

| Other | 3 | – | 11 |

| None | 2 | – | – |

| Sitting duration (hours) | |||

| 0 –2 | – | 1 | – |

| 2 – 4 | – | 5 | 6 |

| 4 –6 | – | 11 | 17 |

| 6–7 | – | 15 | 7 |

| 7 – 8 | 9 | – | – |

| 8 – 9 | 9 | – | – |

| 9 –10 | 6 | – | – |

| 10+ | 6 | – | – |

*Statistically different p<0.001.

BMI, body mass index.

Main results

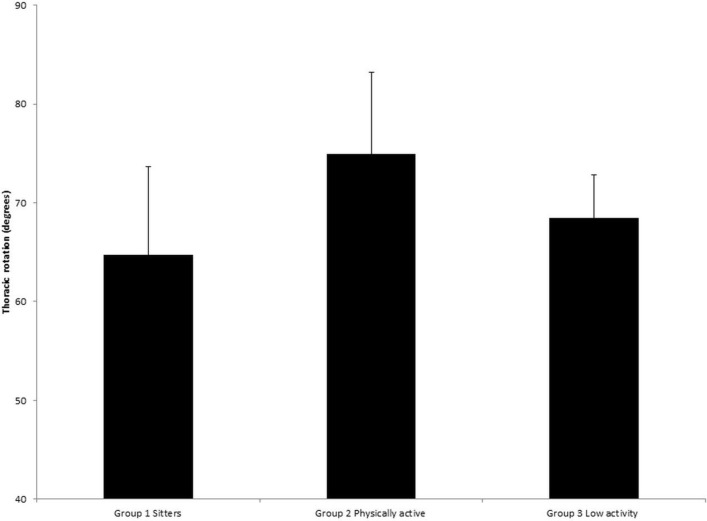

Thoracic spine mobility (mean, SD and 95% CI) for the sitters, physically active and low activity groups were 64.74°±6.33° (62.37° to 67.14°), 75.12°±8.26° (72.61° to 77.31°), 68.28°±4.36° (66.02° to 70.86°), respectively (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Thoracic rotational mobility across groups: sitters, physically active and low activity.

Results from the ANOVA showed a statistically significant difference in thoracic mobility between groups (F (2,56)=20.19, p<0.001), with a large effect size of 0.31. Post hoc comparisons of group mean scores indicated significant differences between the low activity and physically active groups (6.84°, p<0.001), the physically active group and sitters (10.38°, p<0.001), although not between the low activity and sitters (3.54°).

A one-way ANCOVA was conducted having checked data met the assumptions to compare thoracic mobility between groups, while controlling for gender. There was a significant difference between groups (F (2,88)=18.66, p<0.001) with the post hoc analyses confirming differences between the low activity and physically active groups (p<0.001), the physically active group and sitters (p<0.001), although not between the low activity and sitters.

Other analyses: correlational analysis

Across the whole sample, a moderate positive correlation was found between thoracic mobility and exercise duration (r=0.62, p<0.001), a low negative correlation between sitting duration (r=−0.25, p<0.05) and low positive correlation between number of days exercised (r=0. 15, p<0.001).

Discussion

Key results

This is the first rigorous observational study to investigate sedentary behaviour, physical activity and thoracic spine mobility in young adults. While no causal relationship can be inferred from this study, findings including a large effect size, provide preliminary evidence to posit a beneficial effect of physical activity and the deleterious effects of sitting on thoracic spine mobility, a proxy for spinal musculoskeletal health.

Interpretation

The low-activity group contained the highest percentage of women, with more than half the group involved in 90–150 min of physical activity and 4–6 hours sitting duration a week. Failing to meet the national guidelines for exercise31 does appear to impact thoracic mobility, compared with those who are fulfilling the recommendations of >150 min of moderate physical activity per week25 and sit for less than 4 hours per day.24 In contrast, the findings from the physically active group endorse the Public Health England31 recommendation that exercise is beneficial for musculoskeletal health, with those involved in moderate physical activity having significantly greater thoracic spine mobility than those who are more sedentary. There is persuasive evidence from this study of a relationship between prolonged sitting and thoracic mobility, with >10° less mobility for the sitters compared with those who were physically active. Moreover, with sitters having approximately 4° less mobility than those in the low-activity group, our findings also support the need for further investigation of not only increased levels of physical activity, but also reduced sitting duration for optimal spinal musculoskeletal health. Although the majority of individuals in the low-activity group sit between 4 and 7 hours a day (comparable with the findings of the physical-activity group), it appears that some physical activity, although less than the recommended guidelines is beneficial to offset the ‘detrimental’ effects of sitting; with those in the low-activity group having >6° less thoracic mobility than those in the physically activity group.

These findings lend support for those young adults who comply with national guidelines on physical activity25 having better musculoskeletal health. Findings also support the need to further investigate types of physical activity, where consideration is made specifically to biomechanical as well as physiological parameters of physical activity such as exercise intensity. With evidence of associations between thoracic spine mobility and exercise duration (positive), number of days exercised (positive) and sitting duration (negative), further research is now required to investigate the potentially causal relationship of reduced thoracic mobility leading to musculoskeletal complaints such as neck, thoracic and low back pain.

Strengths and limitations

Reported in line with STROBE and employing rigorous methods, including assessor blinding, we have established differences in thoracic mobility in a large population of young adults. While self-reported measures of physical activity and sitting duration potentially lead to underestimation or overestimation of sitting and physical activity behaviours, they are able to capture information relating to activities which are not compatible or insensitive to accelerometry such as water-based activity or cycling and stair climbing, respectively.32

Although not examined here, patterns of sitting are a potentially important consideration in future studies, where breaks have been shown to be beneficial on proinflammatory markers; linked to development of neck–shoulder pain.7 Moreover, future studies could also usefully evaluate other sitting parameters where constrained or poor postures, ergonomic parameters, for example, keyboard position, may place greater loads on musculoskeletal tissues.17 33–35

Generalisability

To enable generalisability to different populations, further studies are required with different age groups and individuals from a range of sociodemographic backgrounds. However, it is likely that this population comprising young adults is an at ‘risk’ group for developing future musculoskeletal complaints, with many likely to work in occupations where a substantial periods of time will be sitting.7 Moreover, this population represents a group where there is potential to influence thoracic spine mobility, with spinal degenerative changes often developing at and beyond the third decade36 and therefore likely less responsive to physical therapy interventions targeting stiff joints and muscles.

Conclusion

This study provides evidence of reduced thoracic mobility in individuals who spend >7 hours a day sitting and <150 min of physical activity a week. With observed associations between thoracic mobility and exercise and sitting duration, further research is now required to explore the possible causal relationship between physical activity behaviours on spinal musculoskeletal health and subsequently their relationship to spinal complaints.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: NRH was the chief investigator leading the study design, analyses and dissemination. KT and GB conducted data collection and preliminary analyses. All authors (NRH, GB, KT, DF and ABR) contributed to analysis and interpretation of results, conclusions and dissemination. NRH drafted the initial manuscript. All authors have read, contributed to and agreed on the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: School of Sport, Exercise & Rehabilitation Sciences.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Raw data are held by the lead author at the University of Birmingham in accordance with guidelines. Data are available by contacting the lead author at n.heneghan@bham.ac.uk.

References

- 1. Owen N. Sedentary behavior: understanding and influencing adults' prolonged sitting time. Prev Med 2012;55:535–9. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Owen N, Healy GN, Matthews CE, et al. . Too Much Sitting. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 2010;38:105–13. 10.1097/JES.0b013e3181e373a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wilmot EG, Edwardson CL, Achana FA, et al. . Sedentary time in adults and the association with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and death: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2012;55:2895–905. 10.1007/s00125-012-2677-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ariëns GA, Bongers PM, Douwes M, et al. . Are neck flexion, neck rotation, and sitting at work risk factors for neck pain? Results of a prospective cohort study. Occup Environ Med 2001;58:200–7. 10.1136/oem.58.3.200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hallman DM, Gupta N, Mathiassen SE, et al. . Association between objectively measured sitting time and neck-shoulder pain among blue-collar workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2015;88:1031–42. 10.1007/s00420-015-1031-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Straker LM, O’Sullivan PB, Smith AJ, et al. . Relationships between prolonged neck/shoulder pain and sitting spinal posture in male and female adolescents. Man Ther 2009;14:321–9. 10.1016/j.math.2008.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hallman DM, Mathiassen SE, Heiden M, et al. . Temporal patterns of sitting at work are associated with neck-shoulder pain in blue-collar workers: a cross-sectional analysis of accelerometer data in the DPHACTO study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2016;89:823–33. 10.1007/s00420-016-1123-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gupta N, Christiansen CS, Hallman DM, et al. . Is objectively measured sitting time associated with low back pain? A cross-sectional investigation in the NOMAD study. PLoS One 2015;10:3 10.1371/journal.pone.0121159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sueki DG, Cleland JA, Wainner RS. A regional interdependence model of musculoskeletal dysfunction: research, mechanisms, and clinical implications. J Man Manip Ther 2013;21:90–102. 10.1179/2042618612Y.0000000027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tsang SM, Szeto GP, Lee RY. Normal kinematics of the neck: the interplay between the cervical and thoracic spines. Man Ther 2013;18:431–7. 10.1016/j.math.2013.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Falla D, Gizzi L, Parsa H, et al. . People With Chronic Neck Pain Walk With a Stiffer Spine. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2017;47:268–77. 10.2519/jospt.2017.6768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Theisen C, van Wagensveld A, Timmesfeld N, et al. . Co-occurrence of outlet impingement syndrome of the shoulder and restricted range of motion in the thoracic spine--a prospective study with ultrasound-based motion analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010;11:135 10.1186/1471-2474-11-135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Berglund KM, Persson BH, Denison E. Prevalence of pain and dysfunction in the cervical and thoracic spine in persons with and without lateral elbow pain. Man Ther 2008;13:295–9. 10.1016/j.math.2007.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Heneghan NR, Rushton A. Understanding why the thoracic region is the ’Cinderella' region of the spine. Man Ther 2016;21:274–6. 10.1016/j.math.2015.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Walser RF, Meserve BB, Boucher TR. The effectiveness of thoracic spine manipulation for the management of musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Man Manip Ther 2009;17:237–46. 10.1179/106698109791352085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huisman PA, Speksnijder CM, de Wijer A. The effect of thoracic spine manipulation on pain and disability in patients with non-specific neck pain: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil 2013;35:1677–85. 10.3109/09638288.2012.750689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Roquelaure Y, Bodin J, Ha C, et al. . Incidence and risk factors for thoracic spine pain in the working population: the French Pays de la Loire Study. Arthritis Care Res 2014;66:1695–702. 10.1002/acr.22323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fujii R, Sakaura H, Mukai Y, et al. . Kinematics of the lumbar spine in trunk rotation: in vivo three-dimensional analysis using magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Spine J 2007;16:1867–74. 10.1007/s00586-007-0373-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Page P. Current concepts in muscle stretching for exercise and rehabilitation. Int J Sports Phys Ther 2012;7:109–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Steene-Johannessen J, Anderssen SA, van der Ploeg HP, et al. . Are Self-report Measures Able to Define Individuals as Physically Active or Inactive? Med Sci Sports Exerc 2016;48:235–44. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hildebrandt VH, Bongers PM, Dul J, et al. . The relationship between leisure time, physical activities and musculoskeletal symptoms and disability in worker populations. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2000;73:507–18. 10.1007/s004200000167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Beach TA, Parkinson RJ, Stothart JP, et al. . Effects of prolonged sitting on the passive flexion stiffness of the in vivo lumbar spine. Spine J 2005;5:145–54. 10.1016/j.spinee.2004.07.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. . Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007;335:806–8. 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dunstan DW, Howard B, Healy GN, et al. . Too much sitting – A health hazard. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2012;97:368–76. 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. National Insititute of Clinical Excellence. Physical Activity: for NHS staff, patients and carers. 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/QS84/chapter/Quality-statement-1-Advice-for-adults-during-NHS-Health-Checks.

- 26. Department of Health. At Least Five a Week: Evidence on the impact of physical activity and its relationship to health. 2004. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/dh.gov.uk/en/publicationsandstatistics/publications/publicationspolicyandguidance/dh_4080994.

- 27. Heneghan NR, Hall A, Hollands M, et al. . Stability and intra-tester reliability of an in vivo measurement of thoracic axial rotation using an innovative methodology. Man Ther 2009;14:452–5. 10.1016/j.math.2008.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Johnson KD, Kim KM, Yu BK, et al. . Reliability of thoracic spine rotation range-of-motion measurements in healthy adults. J Athl Train 2012;47:52–60. 10.4085/1062-6050-47.1.52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bucke J, Spencer S, Fawcett L, et al. . Validity of the digital inclinometer and iphone when measuring thoracic spine rotation. J Athl Train 2017;52:820–5. 10.4085/1062-6050-52.6.05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. Hillsdael, NJ: Erlbaum, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fenton K. Preventing Musculoskeletal Disorders has wider impacts for Public Health. Public Health Matters 2016. https://publichealthmatters.blog.gov.uk/2016/01/11/preventing-musculoskeletal-disorders-has-wider-impacts-for-public-health/. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Miles L. Physical activity and health. Nutr Bull 2007;32:314–63. 10.1111/j.1467-3010.2007.00668.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Szeto GP, Straker LM, O’Sullivan PB. A comparison of symptomatic and asymptomatic office workers performing monotonous keyboard work--2: neck and shoulder kinematics. Man Ther 2005;10:281–91. 10.1016/j.math.2005.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hoe VC, Urquhart DM, Kelsall HL, et al. . Ergonomic design and training for preventing work-related musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb and neck in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;15:CD008570 10.1002/14651858.CD008570.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jun D, Zoe M, Johnston V, et al. . Physical risk factors for developing non-specific neck pain in office workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2017;90:373–410. 10.1007/s00420-017-1205-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Edmondston SJ, Singer KP. Thoracic spine: anatomical and biomechanical considerations for manual therapy. Man Ther 1997;2:132–43. 10.1054/math.1997.0293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.