Abstract

Oligomers of peptides are suspected as the underlying cause of Alzheimer disease. Knowledge of their structural properties could therefore lead to a deeper understanding of the mechanism behind the outbreak of this disease. As a step in this direction we have studied dimers by all-atom molecular dynamics simulations. Equilibrated structures at 300 K were clustered into different families with similar structural features. The dominant cluster has parallel N-terminals and a well defined segment Leu17-Ala21 that are stabilized by salt bridges between Lys28 of one chain and either Glu22 or Asp23 of the other chain. The formation of these salt bridges may be the limiting step in oligomerization and fibrillogenesis.

I. INTRODUCTION

A marker of Alzheimer’s disease is the presence of amyloid fibrils build of insoluble deposits of amyloid beta peptide,1,2 a 39-42 residue long peptide released from the amyloid precursor protein. However, the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease are likely not caused by the presence of fully formed fibril but by the more toxic small oligomeric intermediates in the fibril elongation pathway.3–8 The lack of experimental data on the structure of these small oligomers leaves only computational approaches9 as an alternative. Atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) of peptide fragments allow one to simulate the association of disordered trimers and tetramers that subsequently organized into -sheets.10–12 Coarse-grained simulations have shown spontaneous formation of a 100-peptide long fibrillar structure.13,14 While these studies have demonstrated that simulations can probe the transient (and experimentally not observable) intermediates, they have not yet unveiled the distribution of monomers, dimers, and higher order oligomers in the ensemble of intermediates. Especially, it is not clear whether monomer or dimer exist under physiological conditions. Roher et al.15 reported that a monomer is the predominant species for both and at 7.4, while Hilbich et al.16 claimed that dimers are the predominant species at 7.0 and at physiological salt concentrations. Finally, Barrow et al.17 found a mixture of monomer, dimer, trimer, and tetramer for and .

The disagreement may be, in part, due to sampling difficulties. Conventional all-atom MD simulations with explicit solvent are computationally expensive. Currently, they are restricted to either aggregation of a small number of fragments such as three peptides,12 or stability studies of various dimers with predetermined structures.18,19 Even with these limitations, all-atom MD simulations are confined to few microseconds,20 while protein folding and aggregation occur on time scales larger than milliseconds. In order to overcome this limitation, we use an implicit solvent model which increases the efficiency of protein folding and aggregation studies by a factor of compared to one utilizing an explicit solvent model.21

We have recently investigated the structure of the monomer22 in an implicit solvent. At room temperature, the monomer does not have a unique fold but adopts one of the several low-energy conformations. Three distinct families of mostly random coil-like structures dominate, with one cluster having turn around residues 21-27, one with a partially helical structure, and a third having turn around residues 12-17. The exposed free hydrogen bonding sites indicate that the monomer is soluble. No stable beta structure has been observed. Using the same implicit solvent, we extend these investigation in the present article to the dimerization of peptides as dimers are important intermediates and believed to present at least in low concentration.

Our results rely on simulations where the chains are confined to a sphere of a given radius in order to mimic the crowded cellular environment. Configurations are sampled both by constant temperature MD and replica exchange MD simulations. The latter technique induces a random walk of replicas in temperatures allowing replicas to escape local minima. As a consequence, sampling of low-energy configurations is improved over canonical MD at low temperatures. However, the enhanced sampling, with its possibility to calculate physical quantities reliably even at low temperatures, comes at a price. The random walk in temperature space implies a nonphysical dynamics. Hence, for studying the dynamics on the aggregation pathway we have performed additional constant temperature simulations. Most of them got stuck in local minima, and we used for our analysis only the ones that led to same structure that was observed as global minimum in free energy in the replica exchange simulation.

Our results indicate that the dimer is most stable in a configuration where either the two N-terminals or the two C-terminals are parallel. Such configurations are stabilized by contacts between hydrophobic segments of the monomers, especially the segment Leu-Val-Phe-Phe-Ala of residues 17-21. As for the isolated monomer, each chain has a “U-shape” structure with the longer arm having hydrophilic and charged residue with a lactam turn formed by residues Ala21-Lys28. The U-structure and the turn is stabilized by hydrophobic interactions between Val24 and Lys28 or Asn27 side chains. Unlike for the monomer, the salt bridge between Lys28 and either Glu22 or Asp23 is formed between different chains. Formation of this salt bridge may be a driving force for oligomerization. The region around residues Leu17-Ala21 has a well defined structure and shows considerably smaller structural fluctuations than rest of the peptide. This region is known to be a binding site for various inhibitors designed to suppress fibrillogenesis. Our in silico docking experiments indicate that by binding with this region the inhibitors interfere with salt bridge formation that stabilizes the dimer (and presumably higher oligomers).

II. METHODS

The peptide consists of 39 amino acid residues: (Asp-Ala-Glu-Phe-Arg-His-Asp-Ser-Gly-Tyr-Glu-Val-His-His-Gln-Lys-Leu-Val-Phe-Phe-Ala-Glu-Asp-Val-Gly-Ser-Asn-Lys-Gly-Ala-Ile-Ile-Gly-Leu-Met-Val-Gly-Gly-Val). The total charge of the molecule is . All calculations are carried out with the Assisted Model Building with Energy Refinement23 (AMBER 9.0) package using the all-atom force field ff99.24 The interaction between the peptides and surrounding water is approximated by a generalized Born solvent-accessible surface area25 implicit solvent model (Bond radii , solvent dielectric constant 78.5, surface tension ).

In order to mimic the crowded cellular environment we confine the molecules within a sphere of given radius through adding an attracting harmonic force. The harmonic constraint is when the distance between the center of mass of two molecules exceeded , and zero for shorter distances. In this way, we avoid states in which the separation between the two molecules is too large. Here, is the distance between the center of mass of two molecules, and is a force constant whose value is , and the value of is set . We define the centers of mass for each chain by their N, CA, and C backbone atoms.

Configurations of the system (consisting of the two chains constrained within the above defined sphere) are sampled by replica exchange MD as implemented in the sander module of AMBER9. The basic idea of replica exchange MD is to simulate different copies replicas of the system at the same time but at different temperatures values. Each replica evolves independently by MD and every states , with neighbor temperatures are swapped with a probability

| (1) |

and is the potential energy of the system. A time interval of 0.02 ps is chosen in order to allow the kinetic and potential energy of the system to relax. As a consequence of the exchange move replicas walk between high and low temperatures. The excursions to high temperatures allow the system to cross energy barriers leading to more efficient sampling than if all computing resources would be placed in simulation at the lowest temperature.26,27 In this study, 16 replicas, all starting from a fully extended configuration, are simulated over a range of temperatures from 250 to 500 K. Replica temperatures are maintained at the appropriate temperatures by a combination of velocity reassignment from the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution and Langevin thermostat with a collision frequency28 of . The SHAKE algorithm is used to constraint all bond lengths to their equilibrium distances29 and the nonbonded cutoff distance is maintained at .

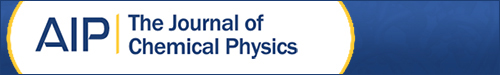

A series of control runs are performed using regular canonical MD starting from different geometries. For this purpose, dimer configurations are generated from the U-shaped-monomer structure22 by orienting and merging the two chains into the desired form, as displayed in Fig. 1: (a) A dimer with parallel N-terminals, (b) one with parallel C-terminals, (c) one where the N-terminal leg of one chain is parallel with the C-terminal leg of the second chain; [(d)–(f)] the corresponding antiparallel configurations; and a linear extended structure (not shown). About 5000 steps of steepest decent minimization are followed by a 200 ps heating stage consisting of steps of MD at 2 fs time steps with a direct space cutoff radius of .

FIG. 1.

Different starting geometries for canonical MD simulations: (a) A dimer with parallel N-terminals, (b) one with parallel C-terminals, (c) one where the N-terminal leg of one chain is parallel with the C-terminal leg of the second chain, [(d)–(f)] and the corresponding antiparallel configurations.

For both constant temperature and replica exchange MD, the initial 5 ns of production runs are discarded and only the latter 85 ns are analyzed. Using the program MMTSB,30 all configurations collected in the replica exchange MD and canonical simulation production phase are grouped according to their geometry by evaluating the root mean square deviation over backbone atoms between configurations. Only clusters containing more than ten members are further analyzed. Calculations of molecular properties rely on all snapshot structures are use the program DSSP (Ref. 31) and the ptraj module of AMBER9.

In order to analyze the binding of certain inhibitor peptides with our final dimer configurations, we use the AUTODOCK4.0 program32 and ClusPro server.33 The interactions of the target peptides , , and with the inhibitor peptides BSB-KLVFF,34 LPFFD,35 LVFFA,36 and GVVIA37 (here BSB stands for beta sheet breaker, and the other capital letters characterize the amino acid sequence of the peptides in the one-letter-code) are calculated and compared to the experimental results available.34,36,37 The docking runs are performed using the Lamarckian genetic algorithm. Mass-centered grid maps are generated by AUTOGRID program with grid spacings of . AMBER force field-based 12-10 and 12-6 Lennard-Jones parameters (supplied with the program package) are used for modeling H-bonds and van der Waals interactions, respectively. The maximum number of energy evaluations is set to per run. All other parameters of the Lamarckian genetic algorithm are set as default. The target sequence and the BSB peptides are generated by deep SWISS PDBVIEWER in pleated sheet with standard and angles of the backbone. AMBER ff99 force fields are implemented for molecular mechanics optimization. The structure of the target and the BSB peptides are optimized with tolerance.

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

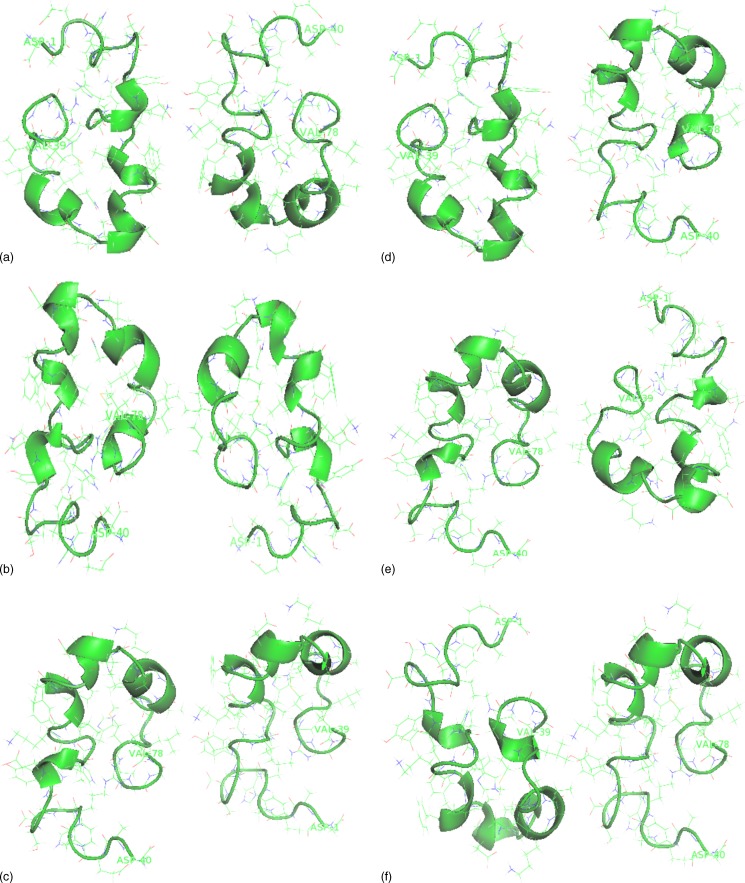

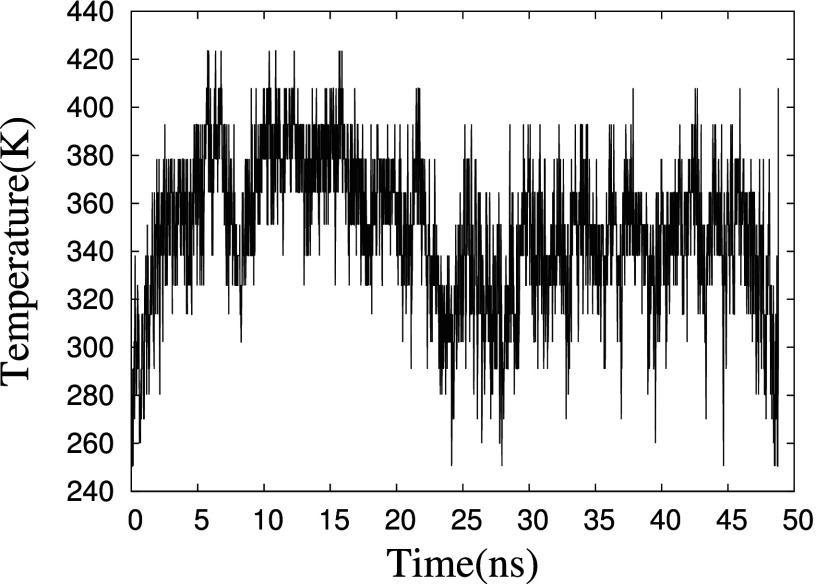

The superior sampling of replica exchange MD relies on the random walk of replicas along the ladder of temperatures. As an example, we show in Fig. 2 the last 50 ns of the random walk for one replica. Associated with it is one in energy allowing the replica to escape local minima. On the other hand, all but one of constant temperature MD simulations got stuck in local minima with the final dimer configurations not differing considerably from the initial ones. The one exception is when the MD simulation started from the extended linear configuration. In this case the final configuration is the dimer with parallel N-terminals of Fig. 3 that has an energy . The same configuration corresponds also to the lowest energy found in the replica exchange MD runs, and is at the dominant configuration. The two chains of the dimer in this configuration are identical in the sense that the values of both chains differ little. The arrangement of the two chains is similar to that of the two strands in a -sheet facing each other in a plane, and slightly displaced over each other. Each chain in the dimer has the U-shape configuration, which is strongly amphipathic, with the longer arm mostly from hydrophilic and charged amino acid residues while the shorter arm formed exclusively with hydrophobic branched residues. The longer arms have both a hydrophobic and a hydrophillic stretch with some ionizable groups in their side chains at positions 22, 23, 27, and 28, and with a turn around Ala21-Asn27 as observed in the monomer.22 The side chains of hydrophobic residues Val(36), Ile(32), Phe(19), and Tyr(10) are pointing outward and hydrophobic patches around 17-21, and the C-terminal exhibits hydrogen bond contacts with residues of the same chain. These findings are in agreement with Fernanda de Felice et al.38 who reported that full length amyloid fibrils are stabilized by the hydrophobic interactions mediated by carboxyl terminal domain of the protein having nonpolar residues, and these interactions are destabilized at low temperature causing disaggregation of . Hence, our results indicate that the contribution of hydrophobic interactions to the stability of aggregates is not a bulk effect but appears already in dimers. This further supports the hypothesis that hydrophobic compounds could be effective in destabilizing and disaggregating amyloid fibrils.

FIG. 2.

Time series of temperature exchange for one of the replica in the replica exchange simulation.

FIG. 3.

(a) The dominant cluster of dimer configurations found by replica exchange sampling; (b) mapping of the binding site (labeled as Leu17-Asp23) for with the BSB peptide KLVFF using docking algorithm.

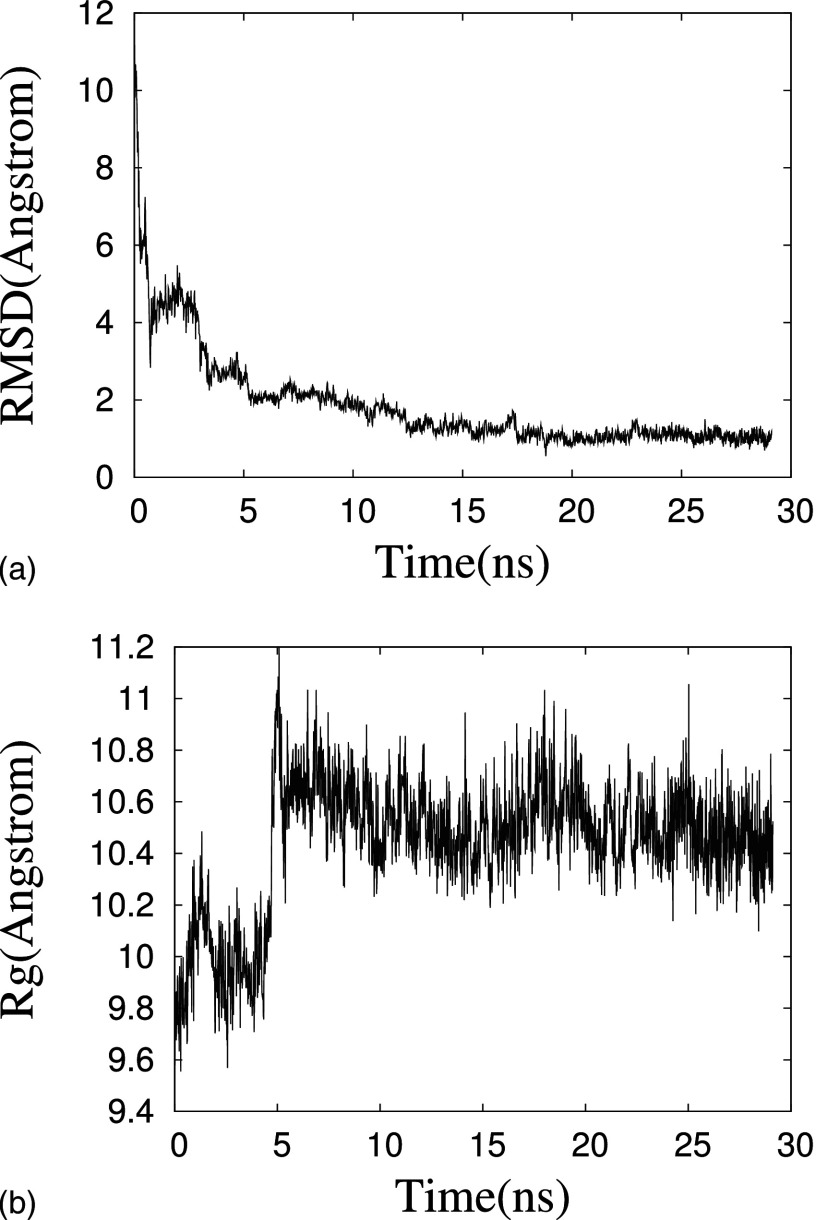

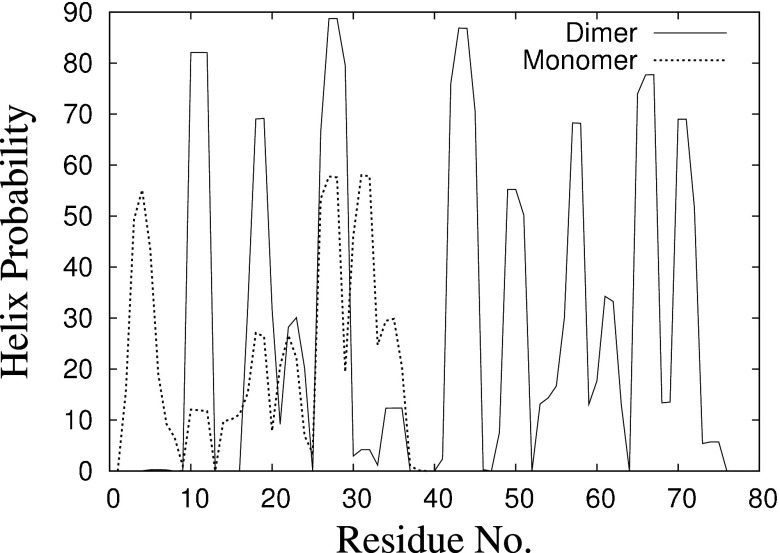

Figure 4(a) shows the root mean square deviation from the initial structure during the trajectory of the one constant temperature molecular dynamic run that did not get trapped in a local minimum. Both this quantity and the radius of gyration in Fig. 4(b) fluctuate strongly in the initial 5 ns, which indicates folding and change in the orientation of the two chains of dimer. After this initial time we find regions with 3-10 helix, -helix, and turn as measured with the DSSP program.31 While monomer do not have a significant amount of helical structure,22 this is different for the dimer. Here, the chains have a propensity for forming helices, indicating that a helix is an intermediate structure adopted by the oligomers during fibril formation, see also Fig. 5. The -strand propensity per amino acid for both monomer and dimer is negligible, with no residue having dihedral angles as typical for a -sheet. This suggests that -sheets do not form in the early stages of the disease when peptides are present in the solvable form. It is rather the changes in the microenvironment of the brain (such as ion concentrations) that leads to the -sheet formation in fibrils.

FIG. 4.

(a) Root mean square deviation to the of dimer conformation and (b) radius of gyration as a function of time during the initial 30 ns production run of an all-atom MD simulations.

FIG. 5.

Helix probability at each residue from sampled conformation of monomer (dotted) and dimer (solid), calculated using program DSSP.

The constant temperature MD run indicates a folding and assembly pathway where the turn around Ala21-Asn27 is formed in the initial 2 ns. The dimer interface is characterized by electrostatic interactions between the two chains, with the largest contribution from the salt bridge between and either or and (where and are the two chains in dimer). We conjecture that this U-shaped bend structure and the corresponding salt bridge formations are the kinetic barrier for fibril formation, and that the lactam bond in helps overcoming this barrier by restraining the two clusters of hydrophobic amino acids in a pocket, in apposition to one another, allowing the salt bridges to form. The fibril structure proposed by Petkova et al.39 indicated that the interior of the -sheet duplex in an individual peptide buries many of the hydrophobic amino acid side chains. Packing these hydrophobic residues requires that the salt bridge is formed which in turn depends on burring of the charged Asp23 and Lys28 in a dehydrated environment. This step may represent a kinetic barrier to fibril formations. Solid-state NMR data also suggest the burial of Lys28 in the fibrils and provide evidence that Lys28 is more protected against alkylation than either Lys16 or the R-amino group in fibrillar , even though all three amino groups are equally susceptible to alkylation in monomeric .40

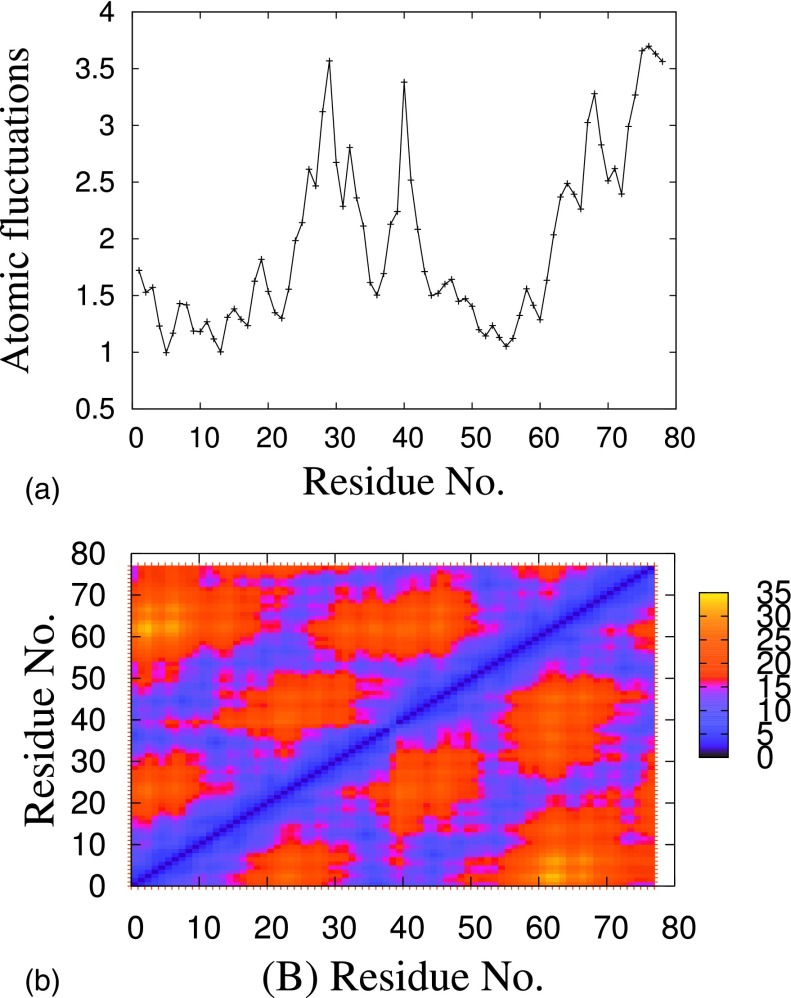

The atomic positional fluctuations of backbone atoms are displayed in Fig. 6(a) for each residue in dimer. The maximum fluctuations are around residues 23-36 in both the chains and have the minimum fluctuations at residues Leu17-Ala23. The fluctuations are not only smaller than in the rest of the peptide but also smaller than observed in the monomer.22 Hence, this short segment with its two Phe residues and the charged residue Lys and Asp seems to be important in the formation of aromatic interactions and salt bridges between the two chains. This is consistent with NMR studies41–43 that suggests a central hydrophobic region, Leu17-Ala21, with well defined structure in the peptide, and this region is found to be critical for fibril formation.44 In our constant temperature molecular dynamic simulation, we observe during the folding and assembly pathway the growth of intramolecular interactions between side chain of with , with , with or , and with . The contact map in Fig. 6(b) also indicates strong interactions between the two N-terminal ends, and further interactions between the two chains around Leu17-Ala23.

FIG. 6.

(a) Atomic fluctuations of dimer backbone. (b) Color coded graph showing the contact of the dimer, calculated by averaging over time and the trajectory. The scale on the right gives the extent of formation of a specific contact. The contacts that are formed with high probability are those between the residue in the central hydrophobic region and the salt bridge between the chains.

The segment (17-23) of the peptide is known as an important binding site for the various inhibitors designed to inhibit fibrillogenesis.34,35 For instance, Tjernberg’s KLVFF peptide inhibitor34 is designed on this region, with good energy scores and frequencies in docking experiments. The interaction and binding with the Leu17-Ala23 fragment are also essential in the -sheet breaking feature of the KLVFF (Ref. 34) and LPFFD (Ref. 35) inhibitors. It is assumed that these BSB peptides work either by disaggregating the oligomers to monomers or by inhibiting the growth of the polymers. Our docking experiments using KLVFF,34 LPFFD,35 LVFFA, and GVVIA (Ref. 37) BSB peptides confirm the interaction with the 17-23 region of the target peptides, i.e., , as shown in Fig. 3. Stabilizing interactions are between side chain of ASP23 in chain and amino group of Lys of inhibitor KLVFF and Lys16 with amino group of Phe4 in BSB peptide. Together with our simulations of the dimer these docking experiments indicate that these BSB peptides act by binding to the 17-23 region fragment, thus inhibiting the formation of the interactions (intramolecular salt bridges and hydrophobic interactions) that otherwise stabilize the dimer or other oligomers, and therefore further inhibiting the fibril formation. This conjecture is also supported by experiments done on cellulose membrane matrix which have shown that the segments and bind radioactive more prominent than the hydrophobic patch in the C-terminal .

IV. CONCLUSION

We have performed replica exchange and constant temperature MD simulations of dimer formation of peptides. Our simulations depend on the use of an implicit solvent. Despite this limitation, our results confirm the importance of hydrophobic forces for stabilization of the dimer or the highmer that has been observed experimentally. They indicate that the parallel conformation of the dimer is preferred over the antiparallel conformation. Our simulations also point out the role of the structural stability of the LVFFA central hydrophobic cluster for stabilization of the parallel dimer structure, and suggest that this stabilization is mainly due to salt bridge between and either or and . Compounds that destabilize and disaggregate amyloid fibrils likely act by interfering with the formation of this salt bridge.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported, in part, by research Grant No. CHE-0809002 of the National Science Foundation (USA). We thank Sandipan Mohanty for useful discussions. All calculations were done on computers of the John von Neumann Institute for Computing, Research Center Jülich, Jülich, Germany.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alzheimer A., Allg. Z. Psychiat. Psych.-Gerichtl. Med. 64, Nr. 1-2, 1907, S. 146–148.

- 2.Stelzmann R. A., Norman Schnitzlein H., and Reed Murtagh F., Clin. Anat. 8, 429 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bitan G., Kirkitadze M. D., Lomakin A., Vollers S. S., Benedek G. B., and Teplow D. B., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 10.1073/pnas.222681699 100, 330 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walsh D. M., Klyubin I., Fadeeva J. V., Cullen W. K., Anwyl R., Wolfe M. S., Rowan M. J., and Selkoe D. J., Nature (London) 10.1038/416535a 416, 535 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kagan B. L. and Azimov R., J. Membr. Biol. 202, 1 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawahara M., Kuroda Y., Arispe N., and Rojas E., J. Biol. Chem. 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14077 275, 14077 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kayed R., Sokolov Y., Edmonds B., McIntire T. M., Milton S. C., Hall J. E., and Glabe C. G., J. Biol. Chem. 10.1074/jbc.C400260200 279, 46363 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quist A., Doudevski L., Lin H., Azimova R., Ng D., and Frangione B., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 10.1073/pnas.0502066102 102, 10427 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malolepsza E., Boniecki M., Kolinski A., and Piela L., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 7835 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cecchini M., Rao F., Seeber M., and Caflisch A., J. Chem. Phys. 10.1063/1.1809588 121, 10748 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu C., Lei H. X., and Duan Y., Biophys. J. 10.1529/biophysj.104.047076 87, 3000 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klimov D. K. and Thirumalai D., Structure (London) 10.1016/S0969-2126(03)00031-5 11, 295 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen H. D. and Hall C. K., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 10.1073/pnas.0407273101 101, 16180 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pellarin R. and Caflisch A., J. Mol. Biol. 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.05.033 360, 882 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roher A. E., Chaney M. O., Kuo Y. M., Webster S. D., Stine W. B., Haverkamp L. J., Woods A. S., Cotter R. J., Tuohy J. M., Krafft G. A., Bonnell B. S., and Emmerling M. R., J. Biol. Chem. 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20631 271, 20631 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hilbich C., Kisters-Woike B., Reed J., Masters C. L., and Beyreuther K., J. Mol. Biol. 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90881-6 218, 149 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barrow C. J., Yasuda A., Kenny P. T. M., and Zagorski M. G. J., Mol. Biol. 225, 1075 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tarus B., Straub J. E., and Thirumalai D., J. Mol. Biol. 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.022 345, 1141 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huet A. and Derreumaux P., Biophys. J. 10.1529/biophysj.106.090993 91, 3829 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Urbanc B., Cruz L., Teplow D. B., and Stanley H. E., Curr. Alzheimer Res. 3, 493 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teplow D. B., Lazo N. D., Bitan G., Bernstein S., Wyttenbach T., Bowers M. T., Baumketner A., Shea J. E., Urbanc B., Cruz L., Borreguero J., and Stanley H. E., Acc. Chem. Res. 10.1021/ar050063s 39, 635 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anand P., Nandel F. S., and Hansmann U. H. E., J. Chem. Phys. 10.1063/1.2907718 128, 165102 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Case D. A., Darden T. A., Cheatham T. E. III, Simmerling C. L., Wang J., Duke R. E., Luo R., Merz K. M., Pearlman D. A., Crowley M., Walker R. C., Zhang W., Wang B., Hayik S., Roitberg A., Seabra G., Wong K. F., Paesani F., Wu X., Brozell S., Tsui V., Gohlke H., Yang L., Tan C., Mongan J., Hornak V., Cui G., Beroza P., Mathews D. H., Schafmeister C., Ross W. S., and Kollman P. A., AMBER 9, University of California, San Francisco, 2006.

- 24.Wang J., Cieplak P., and Kollman P. A., J. Comput. Chem. 21, 1049 (2000). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hawkins G. D., Cramer C. J., and Truhlar D. G., J. Phys. Chem. 10.1021/jp961710n 100, 19824 (1996). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hansmann U. H. E., Chem. Phys. Lett. 10.1016/S0009-2614(97)01198-6 281, 140 (1997). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sugita Y. and Okamoto Y., Chem. Phys. Lett. 10.1016/S0009-2614(99)01123-9 314, 141 (1999). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Izaguirre J. A., Catarello D. P., Wozniak J. M., and Skeel R. D., J. Chem. Phys. 10.1063/1.1332996 114, 2090 (2001). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Gunsteren W. F. and Berendsen H. J. C., Mol. Phys. 10.1080/00268977700102571 34, 1311 (1977). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feig M., Karanicolas J., and Brooks C. L. III, J. Mol. Graphics Modell. 10.1016/j.jmgm.2003.12.005 22, 377 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kabsch W. and Sander C., Biopolymers 10.1002/bip.360221211 22, 2577 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morris G. M., Goodsell D. S., Halliday R. S., Huey R., Hart W. E., Belew R. K., and Olson A. J., J. Comput. Chem. 19, 1639 (1998). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Comeau S. R., Gatchell D. W., Vajda S., and Camacho C. J., Bioinformatics 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg371 20, 45 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tjernberg L., Naslund J., Lindqvist F., Johansson J., Karlstrom A. R., Thyberg J., Terenius L., and Nordstedt C. J., Biol. Chem. 271, 8545 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soto C., Sigurdsson E. M., Morelli L., Kumar R. A., Castano E. M., and Frangione B., Nat. Med. 4, 822 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hetenyi C., Kortvelyesib T., and Botond P. B., J. Med. Chem. 10, 1587 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hetenyi C., Szabo Z., Klement E., Datki Z., Kortvelyesi T., Zarandi M., and Penke B., Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 292, 931 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fernanda De Felice G., Houzel J. -C., Garcia-Abreu J., P. R. F. Louzada, Jr., Afonso R. C., Nazareth M., Meirelles L., Lent R., Neto V. M., and Ferreira S. T., FASEB J. 15, 1297 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petkova A., Ishii T. Y., Balbach J. J., Antzutkin O. N., Leapman R. D., Delaglio F., and Tycko R., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 10.1073/pnas.262663499 99, 16742 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iwata K., Eyles S. J., and Lee J. P. J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 10.1021/ja015735y 123, 6728 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hou L., Shao H., Zhang Y., Li H., Menon N. K., Neuhaus E. B., Brewer J. M., Byeona I. J. L., Ray D. G., Vitek M. P., Iwashita T., Makula R. A., Byla A., and Zagorski M. G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 10.1021/ja036813f 126, 1992 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Riek R., Guntert P., Dobeli H., Wipf B., and Wu Trich K., Eur. J. Biochem. 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02537.x 268, 5930 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang S., Iwata K., Lachenmann M. J., Peng J. W., Li S., Stimson E. R., Lu Y. A., Felix A. M., Maggio J. E., and Lee J. P., J. Struct. Biol. 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4288 130, 130 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fraser P. E., Nguyen J. T., Surewicz W. K., and Kirschner D. A., Biophys. J. 60, 1190 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]