Abstract

Background

Delirium is common among seniors discharged from the emergency department (ED) and associated with increased risk of mortality. Prior research has addressed mortality associated with seniors discharged from the ED with delirium, however has generally relied on data from one or a small number of institutions and at single time points.

Objectives

Analyse mortality rates among seniors discharged from the ED with delirium up to 12 months at the national level.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Analysed data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services limited data sets for 2012–2013.

Participants

Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries aged 65 years or older discharged from the ED. We focused on new incident cases of delirium, patients with any prior claims for delirium, hospice claims or end-stage renal disease were excluded. Sample size included 26 245 delirium claims, and a randomly selected sample of 262 450 controls.

Outcome measures

Mortality within 12 months after discharge from the ED, excluding patients transferred or admitted as inpatients.

Results

Among all beneficiaries, 46 508 (16.1%) died within 12 months, of which 39 404 (15.0%) were in the non-delirium (ie, control group) and 7104 (27.1%) were in the delirium cohort, respectively. Mortality was strongest at 30 days with an adjusted HR of 4.82 (95% CI 4.60 to 5.04). Over time, delirium was consistently associated with increased mortality risk compared with controls up to 12 months (HR 2.07; 95% CI 2.01 to 2.13). Covariates that affected mortality included older age, comorbidity and presence of dementia.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate delirium is a significant marker of mortality among seniors in the ED, and mortality risk is most salient in the first 3 months following an ED visit. Given the significant clinical and financial implications, there is a need to increase delirium screening and management within the ED to help identify and treat this potentially fatal condition.

Keywords: geriatrics, delirium, mortality, claims data

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study included the entire Medicare population aged 65 and older with outpatient claims in the USA, over 5.8 million patients.

We found that delirium is a significant marker of mortality among seniors visiting the ED, and that mortality risk is most prominent in the first three months following an ED visit.

A limitation of this study is that we could not control for delirium severity or duration of illness prior to the diagnosed event as this information was not available in the claims-level data used in our analysis.

Introduction

The emergency department (ED) is often the point of entry for seniors into the healthcare system, and as such plays a unique role in setting the trajectory of care for this rapidly growing and often vulnerable segment of the population. Thus, timely screening of life-threatening conditions such as delirium is critical in the ED.

Delirium is broadly defined as an acute decline in attention and global cognitive functioning,1 which is common and often fatal in older adults.2 In the USA alone, of the nearly 20 million older adults seen in the ED each year,3 approximately 8%–17% present to the ED suffering from delirium.4 Prior research indicates that patients with delirium have a 12-month mortality rate between 10% and 26%,5 which is comparable to patients with sepsis or acute myocardial infraction.6 Additionally, the increased mortality risk for patients with delirium in the ED has been identified at multiple time points, specifically at 3, 6 and 12 months.3 5 7

Furthermore, delirium is also costly and management can be resource intensive. For example, delirium is often associated with increased length of stay among hospitalised patients, may require use of restraints, sedative medications or additional staffing (eg, sitters) and generally linked to greater functional and cognitive decline.8

Despite the growing body of research demonstrating delirium is an independent predictor of mortality, as well as increased costs, management of delirium in the ED has not been well studied. In fact, some studies suggest delirium goes undiagnosed by up to 80% of ED physicians,8 9 highlighting the magnitude of the missed opportunity to improve recognition and management of this potentially fatal condition.

While prior research has addressed the mortality risk associated with seniors discharged from the ED with delirium, much of this research has relied on data from a few, if not a single institution. Furthermore, previous research has typically examined mortality at only single points in time. Our work builds off this growing body of literature by leveraging national claims data to analyse mortality rates among seniors discharged from the ED with delirium at multiple time points up to 12 months, with implications for screening and treatment recommendations.

Methods

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not directly involved as the analysis was conducted using US claims-level data.

Study design and data source

Our study was a retrospective analysis of all available national claims-level data from 2012 to 2013. We analysed data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Research Data Assistance Center data set which includes data for approximately 98% of the US population aged 65 years and older.10 CMS data are one of the richest sources of utilisation information nationally with sizeable samples, documented procedures and diagnoses, verified deaths, beneficiary demographic information and revenue centre details. For our study, we used data for each institutional and non-institutional claim type with each record representing a beneficiary claim.

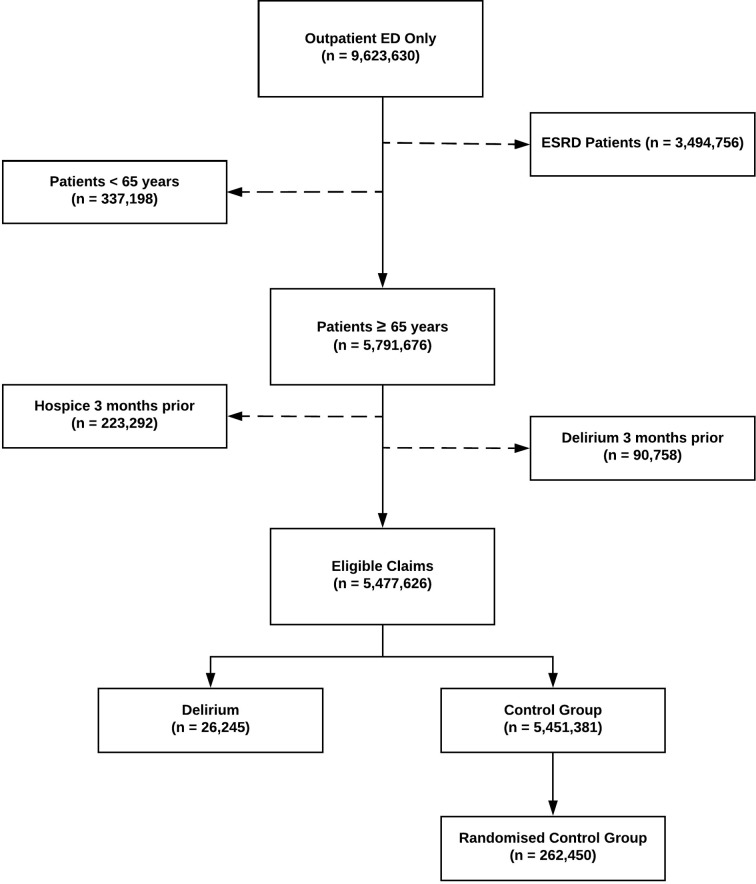

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

An ED-associated claim qualified as an index encounter if it was the beneficiary’s initial ED outpatient-only claim during the study period and if the claim had subsequent claims-level data available for 3 months before and 12 months after index encounter (15 months of available data in total). The 3-month control period prior to index ED encounter was used to exclude beneficiaries with any prior claims for delirium, hospice claims or end-stage renal disease (ESRD) to reduce the potential confounding nature of these factors and to focus largely on new incident cases of delirium. We excluded patients with ESRD from our sample population as prior literature suggests claims data for ESRD are often incompletely documented or not tracked in the Medicare data system with as much rigour as the general Medicare population.11 Index encounters that resulted in observation or an inpatient stay were also excluded due to likelihood that these cases may represent higher acuity conditions. Once exclusion criteria were applied, we removed a total of 3 808 806 claims (90 758 delirium, 223 292 hospice and 3 494 756 ESRD claims) leaving us with a total of 5 477 626 claims for our analyses. See figure 1 for a flow chart showing application of the inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for inclusion/exclusion criteria. ED, emergency department; ESRD, end-stage renal disease.

Cohort selection

Of the 5 477 626 claims, we focused our analyses on two cohorts: a delirium cohort, and a control group of beneficiaries without delirium. The groups were constructed as follows:

Delirium cohort

Of the 5 477 626 eligible claims, delirium was identified based on presence of a qualifying outpatient diagnosis claim that included International Classification of Diseases Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes (293.0, 290.41, 293.89, 780.09, 292.81, 300.11, 290.11, 290.3, 293.1, and categories 308, and 584–586) (see online supplementary appendix 1 for a more detailed description of codes). We limited delirium diagnoses to claims where at least one of these ICD-9 codes was documented at least once within any diagnosis, at which point the claim was flagged as a delirium encounter. We identified a total of 25 980 beneficiaries with qualifying index encounters and a total of 26 245 delirium claims.

bmjopen-2017-021258supp001.pdf (232.6KB, pdf)

Control cohort

The control group consisted of beneficiaries with no delirium diagnosis present. Of the eligible 5 477 626 claims for our analyses, 5 451 381 qualifying index ED claims were eligible for the control group after selection of the delirium cohort from the eligible claims. Considering the size of our control group, we randomly selected from the 5 451 381 potential control beneficiaries using a 10:1 ratio following prior research on recommended statistical practice based on simulation studies of a minimum of 10 events per variable.12 Following random selection, our control group included a total of 251 971 beneficiaries and a total of 262 450 claims.

Mortality

Mortality was flagged for all individuals who died within 12 months from index encounter and flagged only if the death date was verified at 30 days, 90 days, 6 months and 12 months. The total number of deaths recorded for the delirium and control groups at 12 months was 7104 (27.1%) and 39 404 (15.0%), respectively. See table 1 for mortality rate by death date.

Table 1.

Cohort characteristics

| Characteristics | Delirium | Control (no delirium) |

| Total | 26 245 (100) | 262 450 (100) |

| Age | ||

| 65–74 | 8723 (33.2) | 106 163 (40.4) |

| 75–84 | 9500 (36.2) | 96 998 (37.0) |

| ≥85 | 8022 (30.6) | 59 272 (22.6) |

| Mean age | 79 | 77 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 16 279 (62.1) | 160 421 (61.1) |

| Male | 9966 (37.9) | 102 012 (38.8) |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 22 699 (86.5) | 222 177 (84.7) |

| African-American | 2243 (8.5) | 27 328 (10.4) |

| Asian | 345 (1.3) | 3115 (1.2) |

| Hispanic | 473 (1.8) | 4683 (1.8) |

| Native American | 134 (0.51) | 1389 (0.53) |

| Other/unknown | 281 (1.1) | 2852 (1.1) |

| Charlson comorbidity scores | ||

| None (0) | 12 423 (47.3) | 113 743 (43.3) |

| Low (1–4) | 13 182 (50.2) | 141 832 (54.0) |

| Moderate (5–9) | 595 (2.3) | 6553 (2.5) |

| High (10+) | 45 (0.17) | 305 (0.12) |

| Mean CCI score | 4 | 6 |

| Primary diagnosis (ICD-9 codes) | ||

| Infectious diseases (0–139) | 252 (1.0) | 2235 (0.9) |

| Neoplasms (140–239) | 93 (0.4) | 926 (0.4) |

| Mental/neurological (240–289) | 4651 (17.7) | 8547 (3.3) |

| Cardiovascular (390–429) | 1396 (5.3) | 17 038 (6.5) |

| Cerebrovascular (430–459) | 1117 (4.3) | 7814 (3.0) |

| Respiratory (460–519) | 794 (3.0) | 15 802 (6.0) |

| Digestive (460–519) | 312 (1.2) | 13 927 (5.3) |

| Urogenital (580–629) | 1552 (5.9) | 14 509 (5.5) |

| Musculoskeletal (710–739) | 412 (1.6) | 19 779 (7.5) |

| Symptoms (782–789) | 1803 (6.9) | 60 126 (22.9) |

| Injuries (790–799) | 151 (0.6) | 1593 (0.6) |

| Ill defined, skin or missing (680–709) | 58 (0.2) | 5299 (2.0) |

| Endocrine (240–289) | 1463 (5.6) | 10 788 (4.1) |

| Mortality | ||

| 30 days | 3129 (11.9) | 7649 (2.9) |

| 90 days | 4251 (16.2) | 15 267 (5.8) |

| 6 months | 5364 (20.4) | 24 453 (9.3) |

| 12 months | 7104 (27.1) | 39 404 (15.0) |

CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; ICD-9, International Classification of Diseases Ninth Revision.

Statistical analysis

Our analyses focused on two primary areas: (1) the role of delirium as an independent predictor for mortality; and (2) identifying the effect of covariates (age, gender, dementia and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)) on mortality.

We first compared the two cohorts using independent groups t-test and χ2 test for quantitative and categorical variables and found significant differences between the cohorts with respect to demographic and clinical measures. Members of the delirium cohort were more likely than controls to be older (mean age: 79 vs 77), more likely to have a lower level of illness and severity burden (mean CCI: 4 vs 6)13 and more likely to have a primary diagnosis of mental/neurological clinical classification. The cohorts did not differ with respect to gender or ethnicity as both cohorts’ members were more likely to be Caucasian women (see table 1).

Time 0 was defined as date of index encounter and days between death date and index encounter was calculated for the model. In addition, beneficiaries were censored at the end of the 12-month follow-up period if death did not occur or no subsequent claims, whichever occurred earlier. We then used the exponential model for the survival time distribution to estimate yearly mortality rates for the delirium and control cohort using an unadjusted Kaplan-Meier survival curve. In addition, a score test (univariate Cox proportional hazards model) was used as a comparison to the unadjusted Kaplan-Meier survival curves.14

Additionally, to adjust for possible prognostic factors of delirium on mortality, we used a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model with the following covariates: age, gender, dementia and comorbidity (as defined by CCI). To address the potential interaction of delirium on mortality based on these characteristics, we evaluated all covariates in the multivariable Cox model, and then selected statistically significant interactions for further testing. In addition, to confirm results we reran these analyses using multiple randomly selected samples from within the control group and found no statistically significant differences.

Results

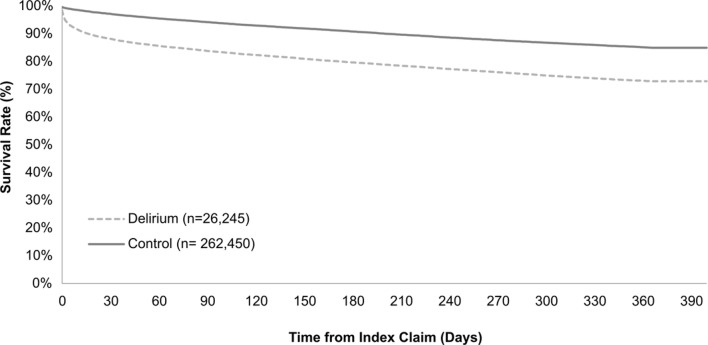

During the 12-month study period 288 695 claims were included in our analysis sample, of which 26 245 comprised the delirium cohort and 262 450 control claims. Beneficiaries were largely similar with respect to gender, and primary diagnosis distributions, however when evaluating comorbidity scores, beneficiaries had higher scores in the control group suggesting higher risk of mortality (see table 1). Among all beneficiaries, 46 508 (16.1%) died within 12 months, of which 39 404 (15.0%) were in the non-delirium (ie, control group) and 7104 (27.1%) were in the delirium cohort, respectively. In the delirium cohort, Kaplan-Meier survival curves decreased rapidly during the first 30 days after the index visit and thereafter continued to decline at a slower pace in comparison to the control group. At 30 days after index visit, the survival rate for beneficiaries with delirium was 88.2%, while the control group had a survival rate of 97.6%.

Results from the univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards model for 30 days, 90 days, 6 months and 12 months are reported in table 2. Our unadjusted results for delirium and mortality were strongest at 30 days as illustrated in the Kaplan-Meier survival curve (HR 4.35; 95% CI 4.17 to 4.54) (see figure 2). Even after adjusting for covariates, delirium was still independently associated with approximately a fivefold increase in mortality during the 30-day follow-up period (HR 4.82; 95% CI 4.60 to 5.04). Over time from index ED encounter, delirium was still consistently associated with an increased risk of mortality compared with the control group. However, mortality risk (while still significant) did decrease over time until 12 months (HR 2.07; 95% CI 2.01–2.13).

Table 2.

Cox proportional HRs in intervals to 12-month mortality

| Mortality rate | Variable | Univariate | Multivariate |

| 30 days | Delirium/control | 4.35* (4.17 to 4.54) | 4.82* (4.60 to 5.04) |

| Age | 1.06* (1.05 to 1.06) | 1.06* (1.05 to 1.06) | |

| Male/female | 0.72* (0.69 to 0.74) | 0.70* (0.67 to 0.73) | |

| CCI | 1.29* (0.77 to 1.28) | 1.30* (1.29 to 1.31) | |

| Dementia | 1.84* (1.75 to 1.94) | 1.44* (1.35 to 1.53) | |

| Delirium†dementia | – | 0.41* (0.36 to 0.45) | |

| 90 days | Delirium/control | 3.02* (2.14 to 2.30) | 3.27* (3.15 to 3.40) |

| Age | 1.06* (1.05 to 1.06) | 1.06* (1.05 to 1.06) | |

| Male/female | 0.74* (0.72 to 0.76) | 0.72* (0.70 to 0.75) | |

| CCI | 1.32* (1.31 to 1.32) | 1.32* (1.31 to 1.33) | |

| Dementia | 2.12* (2.04 to 2.20) | 1.58* (1.51 to 1.65) | |

| Delirium†dementia | – | 0.48* (0.44 to 0.52) | |

| 6 months | Delirium/control | 2.42* (2.35 to 2.49) | 2.55* (2.47 to 2.64) |

| Age | 1.06* (1.05 to 1.06) | 1.06* (1.05 to 1.06) | |

| Male/female | 0.76* (0.74 to 0.78) | 0.73* (0.71 to 0.75) | |

| CCI | 1.31* (1.30 to 1.31) | 1.31* (1.31 to 1.32) | |

| Dementia | 2.25* (2.18 to 2.31) | 1.64* (1.58 to 1.70) | |

| Delirium†dementia | – | 0.53* (0.49 to 0.57) | |

| 12 months | Delirium/control | 2.02* (1.96 to 2.07) | 2.07* (2.01 to 2.13) |

| Age | 1.06 (1.05 to 1.06) | 1.06* (1.05 to 1.06) | |

| Male/female | 0.76* (0.75 to 0.78) | 0.73* (0.71 to 0.74) | |

| CCI | 1.30* (1.29 to 1.31) | 1.30* (1.29 to 1.31) | |

| Dementia | 2.28‡ (2.23 to 2.34) | 1.62* (1.57 to 1.66) | |

| Delirium†dementia | – | 0.60* (0.56 to 0.64) |

Data are HRs for univariate and multivariate for time periods to 1-year mortality rate (95% CI).

Of 277 951 patients, 46 508 died (16.7%) in both groups, of which 39 404 (15.0%) were in the control group (no delirium) and 7104 (27.1%) were in the delirium cohort, respectively.

*P<0.001.

†Indicates interaction.

CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Assessing changes over time in the unadjusted effect of delirium on mortality in comparison to the control group (no delirium). The dotted line represents patients with delirium and when compared with the control group the survival rate decreased rapidly during the first 30 days after the index visit and continued to decline slowly.

Other covariates that affected mortality rate included older age and higher comorbidity scores. However, women with delirium had a decreased risk of mortality compared with men with delirium (HR 0.73; 95% CI 0.71 to 0.74) at 12 months (see table 2).

The presence of dementia, on the other hand, had a stronger association in the univariate model, however our adjusted multivariate model indicated dementia was not a significant predictor of mortality and instead associated with a significant protective effect on mortality. This protective effect is demonstrated by the significant statistical interaction between delirium and dementia (p≥0.001) while adjusting for covariates (HR 0.60; 95% CI 0.56 to 0.64).

Discussion

Our study found that delirium is an independent predictor of mortality among ED patients diagnosed with delirium in the ED compared with ED patients without delirium, even after adjusting for confounding factors such as age, gender, comorbidity and dementia. While delirium had a strong effect on mortality during the entire 12-month follow-up period, the strongest association was at 30 days following index ED visit.

Generally, our findings are consistent with prior research examining delirium and mortality risk. For example, Inouye et al observed that patients with delirium discharged from the ED had a significantly higher mortality risk at 3 months compared with a comparable control group (14% vs 8%), and we found similar unadjusted results at 3 months (16% vs 6%). Similarly, our findings report a twofold mortality risk for patients with delirium at 12 months following an ED visit (HR 2.07; 95% CI 2.01 to 2.13) in line with McCusker et al’s (HR 2.11; 95% CI 1.18 to 3.77), after adjusting for covariates. However, our results indicate a higher risk of mortality compared with prior research at 6 months, as Han et al found seniors to be 1.7 times more likely to be at risk for mortality (HR 1.72; 95% CI 1.04 to 2.86), compared with our study which found the risk to be over 2.5 times more likely at 6 months (HR 2.55; 95% CI 2.47 to 2.64). In addition, our findings are also consistent with prior research on delirium as an independent indicator for mortality in the inpatient setting.3 For instance, past studies report a twofold increase in mortality risk among patients with delirium, and our results point to a similar twofold increase in mortality during 12-month follow-up.

Our findings are also in line with prior research highlighting the role of dementia superimposed on delirium and its protective effect on mortality.3 Others have theorised as to why this is the case, however further research is needed in distinguishing acute behavioural changes of delirium with the longer term changes associated with dementia to properly evaluate its impact. One reason may be that delirium may be harder to distinguish in patients with dementia, leading to misclassification in claims data. Further research is needed in distinguishing acute behavioural changes of delirium with the longer term changes associated with dementia and the proper screening and measurements.

Given the clinical as well as cost implications, our results call for an increase in screening and management of delirium in the ED. A practical first step is through implementation of a validated delirium screening tool into the ED clinical workflow. Since the majority of patients with delirium have a clinically subtle presentation, it is often missed by providers, which is likely to be the case in a busy ED. While multiple resources exist for delirium screening, the most widely used in the inpatient setting is the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM). The brief CAM (b-CAM) is a modified and validated screening tool for delirium and is one of, if not the only instrument validated for use in the ED setting.15 16 The b-CAM takes less than 2 min to perform, is highly reliable, easy to use and requires minimal training, all of which make it an ideal instrument for an ED.17 While other validated screening instruments are available such as the Delirium Rating Scale, the Nurses Delirium Screening Checklist, or the 4As test, many of these tools were not designed for use in the ED and either require specialised training or more time to complete than is often available in an ED encounter.18

A growing number of EDs specialising in geriatric care (ie, geriatric EDs) are already incorporating delirium protocols and screening instruments into their ED workflow. In fact, the geriatric ED guidelines, endorsed by leading professional societies in emergency medicine, nursing and geriatrics, identify delirium screening, and specifically the b-CAM as a recommended screening instrument for use in the EDs. The Society for Academic Emergency Medicine has even recommended delirium screening as a key quality indicator for geriatric emergency care underscoring the importance of detection and management of delirium in the ED.2 15

While screening for delirium is an important first step, screening alone is insufficient and must be followed by clinical intervention to be effective. Based on screening results, decreased use of psychoactive medication or other non-pharmacologic approaches such as increased mobilisation (ie, reduced of physical restraints, bladder catheters), and reorienting the patient through cognitive stimulation are examples of interventions used in the inpatient setting that may also be appropriate for the ED.7 While it remains unclear whether instruments such as the b-CAM or follow-up interventions used in the inpatient setting are associated with reduced mortality risk in the ED, incorporating a delirium instrument into ED workflows represents an important first step to more reliably detect delirium in the ED. Future research will then need to address the most effective screening and treatment protocols.

Limitations

Our study used national claims-level data, which poses several limitations. The date of claims submission does not necessarily reflect date of service, however these differences are often considered marginal. Additionally, claims data lack information on severity and duration of illness prior to the diagnosed event. While we attempted to address this issue by including a 3-month control period prior to qualifying index encounters and focusing on outpatient claims only, this still did not address the severity of delirium, which is likely to impact mortality risk.

Furthermore, we identified 26 245 (0.35%) patients ≥65 with delirium, which is lower compared with rates of delirium in the ED widely reported in literature, which ranges anywhere from 3.6% to 35% with a mean of 17.5%.4 5 9 Our lower incidence of delirium based on available claims may reflect a failure to diagnose, failure to code or a lower rate of patients with delirium in EDs. This potential absence of delirium diagnoses from a national claims database may limit the generalisability of our findings in helping capture the true impact of delirium on mortality.

Conclusions

Our study of national claims-level data demonstrates that delirium is a significant marker of mortality among seniors visiting the ED, and that mortality risk is most prominent in the first 3 months following an ED visit. Given the significant clinical as well as financial implications associated with seniors discharged from the ED with delirium, there is a need to increase delirium screening and management within the ED to help identify and treat underlying conditions. Specifically, future research is needed to focus on implementation and dissemination of existing delirium protocols (ie, screening and follow-up interventions) for the ED and whether doing so helps reduce mortality risk in seniors discharged from the ED with this fatal and potentially avoidable condition.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JI, TK, AL and KK contributed to study design. JI and TK performed the data analysis. JI led drafting of the manuscript, with additional manuscript writing performed by AL and KK. All authors had full access to all the data including statistical reports and tables in the study and can take full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Albert M, McCaig L, Ashman J. Emergency department visits by persons aged 65 and over. United States: NCHS Data Brief, 2013:130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fong TG, Tulebaev SR, Inouye SK. Delirium in elderly adults: diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol 2009;5:210–20. 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kakuma R, du Fort GG, Arsenault L, et al. Delirium in older emergency department patients discharged home: effect on survival. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:443–50. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51151.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Inouye SK, Westendorp RGJ, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. The Lancet 2014;383:911–22. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60688-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McCusker J, Cole M, Abrahamowicz M, et al. Delirium predicts 12-month mortality. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:457–63. 10.1001/archinte.162.4.457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gower L, Gatewood M, Kang C. Emergency Department Management of Delirium in the Elderly Western. Journal of Emergency Medicine 2012;2:194–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Han J, Wilson A, Ely W. Delirium in the older emergency department patient - a quiet epidemic emergency medicine clinics of North America. 3, 2010:611–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Han JH, Zimmerman EE, Cutler N, et al. Delirium in Older Emergency Department Patients: Recognition, Risk Factors, and Psychomotor Subtypes. Academic Emergency Medicine 2009;16:193–200. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00339.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Han JH, Shintani A, Eden S, et al. Delirium in the Emergency Department: an Independent Predictor of Death Within 6 Months. Ann Emerg Med 2010;56:244–52. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tyree P, Lind B, Lafferty W. Challenges and Advantages of Using Medicare Claims Data for Utilization Analysis. The American Journal of Medicine 2006;4:269–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wolfe R. Survival analysis methods for the end stage renal disease program in medicare: Kidney Failure & the Federal Government, 1991:353–75. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ogundimu EO, Altman DG, Collins GS. Adequate sample size for developing prediction models is not simply related to events per variable. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;76:175–82. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.02.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Smith B, Smith T, Meier K. Cox proprtional hazards modeling: hands-on survival analysis: Department of Defense Center for Deployment Health Research, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15. De J, Wand A. Delirium screening: a systematic review of delirium screening tools. The Gerontologist 2015;55:1079–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wei LA, Fearing MA, Sternberg EJ, et al. The confusion assessment method: a systematic review of current usage. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:823–30. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01674.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mariz J, Castanho T, Teixeira J, et al. Delirium Diagnostic and Screening Instruments in the ED: An Up-to-Date Systematic Review. Journal of American Geriatics Society 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grover S, Kate N. Assessement Scales of Delirium. World Journal of Psychiatry 2012;2:58–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-021258supp001.pdf (232.6KB, pdf)