Abstract

Introduction

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) is generally used for neutropaenia. Previous experimental studies revealed that G-CSF promoted neurological recovery after spinal cord injury (SCI). Next, we moved to early phase of clinical trials. In a phase I/IIa trial, no adverse events were observed. Next, we conducted a non-randomised, non-blinded, comparative trial, which suggested the efficacy of G-CSF for promoting neurological recovery. Based on those results, we are now performing a phase III trial.

Methods and analysis

The objective of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of G-CSF for acute SCI. The study design is a prospective, multicentre, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled comparative study. The current trial includes cervical SCI (severity of American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale B/C) within 48 hours after injury. Patients are randomly assigned to G-CSF and placebo groups. The G-CSF group is administered 400 µg/m2/day×5 days of G-CSF in normal saline via intravenous infusion for 5 consecutive days. The placebo group is similarly administered a placebo. Our primary endpoint is changes in ASIA motor scores from baseline to 3 months. Each group includes 44 patients (88 total patients).

Ethics and dissemination

The study will be conducted according to the principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and in accordance with the Japanese Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act and other guidelines, regulations and Acts. Results of the clinical study will be submitted to the head of the respective clinical study site as a report after conclusion of the clinical study by the sponsor-investigator. Even if the results are not favourable despite conducting the clinical study properly, the data will be published as a paper.

Trial registration number

UMIN000018752.

Keywords: neurological Injury, spine, clinical trials

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Novel drug therapy for acute spinal cord injury (SCI) is much needed.

Randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blinded design can eliminate bias.

Patients with acute SCI are difficult to recruit to the trial.

Patient’s neurological status in acute phase is unstable, possibly resulting in dispersion of the patient’s background.

Concealment must be performed very strictly because granulocyte colony-stimulating factor apparently increases white blood cell count.

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a devastating injury by which the patient can suffer from long-lasting severe sequelae including palsy of extremities, sensory disturbance, bowel/bladder/sexual dysfunction and neuropathic pain. Conceptually, SCI is divided into two chronological phases: a primary and a secondary phase. Primary injury is mechanical damage to spinal cord tissue itself caused by fracture and/or dislocation or compression. Secondary injury is triggered by the primary injury and is a biological reaction of the spinal cord, which includes ischaemia, haemorrhage, excitotoxicity, hyperpermeability and inflammation.1 Because secondary injury can be the main target of treatment, extensive laboratory and clinical investigation of neuroprotection is needed to manage secondary injury.2

To date, the only approved neuroprotective therapy for SCI is massive methylprednisolone sodium succinate (MPSS) therapy based on the NASCIS 2 study.3 However, recent reports revealed that MPSS shows only a modest effect for SCI. In addition, several reports have described adverse events induced by MPSS for SCI including infections (pneumonia, urinary tract infection) and gastrointestinal disorders (gastric ulcer, among others).4 Therefore, the use of MPSS for SCI has become controversial.5 Accordingly, a new therapeutic drug for SCI is desirable.

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF, generic name: filgrastim) is a growth factor that affects the haematopoietic system, promoting differentiation, proliferation and survival of granulocytes.6 Clinically, in Japan, G-CSF is administered to patients with leucopenia, and to peripheral stem cell transplantation donors, G-CSF is administered to mobilise hematopoietic stem cells into the peripheral blood.7 In the central nervous system, G-CSF has properties to mobilise the movement of B cells into the brain8 and spine and, in a stroke model, has shown neuroprotective properties.9 In other countries, clinical studies of the effects of G-CSF in cerebral infarction have been reported.10

To prove the hypothesis that G-CSF has neuroprotective properties against SCI, G-CSF was administered to rat and mouse animal models of SCI, and hind limb function improved significantly after administration of G-CSF. Further investigations into the mechanism of action of G-CSF in SCI were conducted. Data obtained to date identify the following properties of G-CSF: (1) mobilisation of bone marrow-derived stem cells causing their biointegration at the site of SCI,11 (2) direct inhibition of nerve cell death,12 (3) protection of the myelin sheath by inhibiting oligodendrocyte cell death,13 (4) inhibition of inflammatory cytokine expression (TNF-α, IL-1β)13 and (5) promotion of neovascularisation.14 These properties suggest that G-CSF has a neuroprotective effect in acute SCI.

Based on these properties, a phase I/IIa clinical study was conducted where the main objective was to confirm the safety and feasibility of G-CSF for treatment of patients with acute SCI.15 This study was an open-label, dose-titrating study with no control group. As the initial step, 5 patients were given 5 µg/kg/day of G-CSF for 5 consecutive days by intravenous infusion, and as the second step, 11 patients were given 10 µg/kg/day of G-CSF for 5 consecutive days by intravenous infusion. No serious adverse events were noted, and the safety of G-CSF administration in patients with acute SCI was confirmed.15

As a next step, to validate the efficacy of G-CSF in neuroprotective treatment, a multicentre, prospective, non-randomised, non-blinded, comparative control study (phase IIb clinical trial) was conducted.16 Based on the results of the previous phase I/IIa clinical trial, the dosage and duration of treatment with G-CSF in this study was 10 µg/kg/day for 5 consecutive days. Patients with acute cervical SCI (within 48 hours of injury) were registered in the clinical trial and allocated to either the G-CSF group (G-CSF 10 µg/kg/day×5 days intravenous infusion) or control group (no G-CSF administration) at each treatment facility. A total of 19 patients in the G-CSF group and 26 patients in the control group were observed for 3 months or longer. American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) motor score (motor: 0–100 points) was compared between the groups. ASIA motor scores were 26.1±18.9 in the G-CSF group and 12.2±14.7 in the control group showing a significant improvement of motor paralysis in the G-CSF group (p<0.01). In addition, in cases that could be followed for 1 year or longer, a significant improvement of ASIA motor score was observed in the G-CSF group.16

Based on results of these preclinical and early phase clinical trials, we are now conducting a phase III trial.

Specific objective

The objective of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of G-CSF for improving motor paralysis in acute SCI.

Methods and analysis

Design of the study

The study design of the current trial is a prospective, multicentre, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled comparative study.

Study procedures

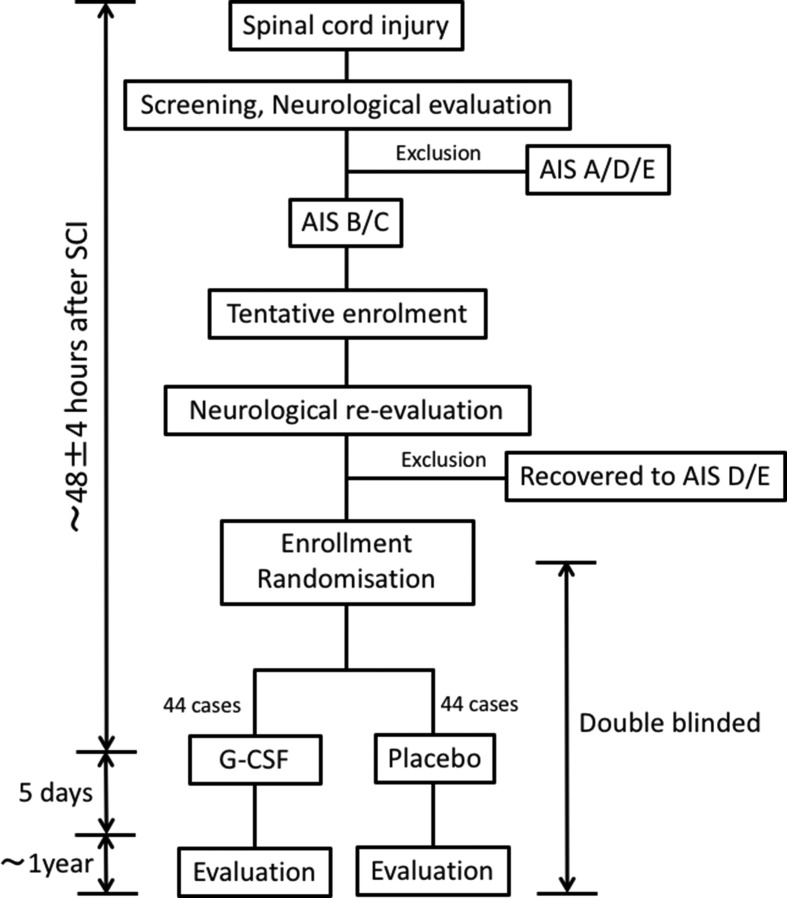

The study outline is shown in figure 1. Patients will be randomly assigned to G-CSF and placebo groups. A central registration system will be used for dynamic randomisation into the investigational treatment group (G-CSF) and control group (placebo) based on age at registration (16–64 years of age or 65–84 years of age) and severity of paralysis (AIS B or C) at 48 hours after injury. The surgical stabilisation and/or decompression was not included in stratification. Initially, screened patients with severity AIS B/C will be tentatively enrolled. Initial screening of the patients include clinical laboratory test, imaging studies including X-ray, MRI and CT and neurological/functional evaluations.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram showing trial timeline. Cervical SCI with severity of AIS B/C within 48 hours after injury is recruited. Patients are randomly assigned to G-CSF and placebo groups. The G-CSF group is administered G-CSF in normal saline via intravenous infusion for 5 consecutive days. The placebo group is similarly administered a placebo. G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; SCI, spinal cord injury.

Neurological reassessment will be performed 48±4 hours after SCI and the patients who will recover to severity AIS D will be excluded. The patients with severity AIS B/C at neurological reassessment 48±4 hours after SCI will be enrolled and randomly allocated to either the investigational treatment group (G-CSF) or control group (placebo) in a 1-to-1 ratio. The subject registration centre uses a programme based on an appropriate computer algorithm to allocate patients into groups. The first dose of investigative drugs will be administered to the patients after reassessment of neurological status and enrolment 48±4 hours after SCI.

The G-CSF group will be administered 400 µg/m2/day×5 days of G-CSF in normal saline via intravenous infusion for 5 consecutive days. The placebo group will be similarly administered a placebo. The first dose of investigative drugs will be administered to the patients 48±4 hours after SCI. The dosing schedule will be once a day in every morning (09:00–10:00 hours) for consecutive 5 days even in case that the first dosing was performed at night because of restriction on practices. Investigational drugs including both G-CSF and placebo will be stored in refrigerator which will be kept between 1 and 6°C and have temperature-logger in pharmacies in each participating institutes. The investigational drugs are packaged in ample with label only printed as serial numbers, 10 amples are packed in one box with label only printed serial numbers. Web-based allocation system will show the serial number of investigational drug which must be used to respective patients to ensure blinding.

We decided dosage of drug based on our previous non-randomised early phase clinical studies. On phase I/IIa clinical study, of which study design was open-label, dose-titrating study with no control group, patients with SCI who were administered 10 µg/kg/day G-CSF for 5 days showed marked elevation of white blood cell number (reached nearly 50 000/μL, of which white blood cell (WBC) number might cause adverse effects of G-CSF) during G-CSF administration.15 Therefore, we decided to withdraw additional titration. In addition, next phase of clinical study, of which design was multicentre, prospective, non-randomised, non-blinded, comparative control study, showed suggestive efficacy of G-CSF (10 µg/kg/day for 5 days) for acute SCI.16 Based on those results, we finally decided the dosage of G-CSF as 10 µg/kg/day×5 days for 5 days. In the current clinical trial, the dosage of G-CSF is written as 400 µg/m2/day (=10 µg/kg/day) according to the Japanese Pharmaceutical and Medical Device Agency’s (PMDA) instruction for consolidation with product labelling.

We decided to 48 hours after SCI as the therapeutic time window because our previous multicentre, prospective, non-randomised, non-blinded, comparative control study, which recruited patients with SCI within 48 hours after injury, showed that there was no significant difference in neurological outcome between the patient administered G-CSF very early after the injury and 48 hours after injury.16

Allocation will be concealed between blinded evaluators of efficacy/safety and those for laboratory data, as G-CSF markedly increases white blood cell counts that can reveal patient treatment.

Our primary endpoint is changes in ASIA motor scores (international standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury (ISNSCI),17 online supplementary figure 1) from baseline to 3 months calculated as follows: 3 months ASIA motor score change=3 months ASIA motor score – pretreatment ASIA motor score. To maintain consistency of neurological assessment among the each evaluators, attending lecture and e-learning (in website of International Spinal Cord Society: http://www.elearnsci.org/) of ASIA/ISNSCI scoring system is mandatory for every investigators participating to the present trial.

bmjopen-2017-019083supp001.jpg (958.1KB, jpg)

Secondary endpoints are as follows. (1) Change in ASIA motor scores17 at 6 months and 12 months after G-CSF administration compared with pretreatment. (2) Changes in sensory paralysis over time: change in ASIA sensory scores at 3 months, 6 months and 12 months after G-CSF administration compared with pretreatment. (3) Severity of functional compromise because of paralysis: AIS before administration and at 3, 6 and 12 months after administration of G-CSF. (4) Percentage of responders: percentage of patients whose AIS improved by 1 grade or more at 3, 6 and 12 months after administration compared with before administration of G-CSF. (5) Neurological level of injury (NLI): percentage of patients whose NLI decreased by 1 grade of more at 3, 6 or 12 months after administration of G-CSF compared with pretreatment. (6) SCIM18: change in SCIM scores at 3, 6 and 12 months after G-CSF administration compared with pretreatment (7) EQ-5D19: measured EQ-5D efficacy scores at 3, 6 and 12 months after G-CSF.

To strengthen the analysis, more strict blindness of assessment by the evaluator for outcome measures is ideal. Therefore, every prior score/measurement should be blinded and/or not the same person should assess every midpoint motor/sensory functional measurement. However, PMDA instructed us to assess one patients’ functional evaluation by one evaluator for consistent assessment in respective patients. PMDA considers the consistency of assessment in respective patients is more important.

The precise explanation of abovementioned outcome measures is as follows (online supplementary figures). ASIA motor score is determined by examining a function of 10 key muscles with manual muscle testing (MMT) in the supine position.17 The score ranges from 0 to 25 for each extremity (MMT 0–5 in five muscles in each extremity), totalling 0–50 for the upper limbs and 0– 50 for the lower limbs, resulting in total of ASIA motor score ranges from 0 to 100. ASIA motor score shows the degree of motor impairment induced by SCI (online supplementary figure 1).17 ASIA sensory scores are determined by sensory testing of a key point in each of the 28 dermatomes (from C2 to S4-5) on the each side of the body. Two aspects of sensation are examined, light touch and pin prick, at all the key points. Light touch and pin prick sensation are separately scored on a three-point scale: 0=absent, 1=altered, 2=normal or intact. As a result, ASIA sensory scores range from 0 to 112 (online supplementary figure 1) in light touch and pin prick, respectively.17 AIS is used for gross grading of impairment: A=Complete: No sensory or motor function is preserved in the sacral segments S4-S5. B=Sensory incomplete: Sensory but not motor function is preserved below the neurological level. C=Motor incomplete: Motor function is preserved below the neurological level, and more than half of key muscle functions below the single NLI have a muscle grade less than 3 (Grades 0–2). D=Motor incomplete: Motor function is preserved below the neurological level, and at least half (half or more) of key muscle functions below the neurological level have a muscle grade >3. E = Normal:17 If sensation and motor function as tested are graded as normal in all segments, and the patient had prior deficits, then the AIS grade is E (online supplementary figure 1, footnote).17 NLI refers to the most caudal segment of the cord with intact sensation and antigravity muscle function strength, provided that there is normal (intact) sensory and motor function rostrally (online supplementary figure 1, footnote).17 SCIM is disability scale developed specifically for patients with spinal cord lesions in order to make the functional assessments of patients with paraplegia or tetraplegia more sensitive to changes18. The SCIM includes the following areas of function: self-care (subscore (0–20), respiration and sphincter management (0–40) and mobility (0–40). Each area is scored according to its proportional weight in these patients’ general activity.18 The final score ranges from 0 to 100 (online supplementary figures 2–4). EQ-5D essentially consists of two pages19 (online supplementary figures 5 and 6): the EQ-5D descriptive system and the EQ visual analogue scale (EQ VAS). The descriptive system comprises five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. Each dimension has five levels: no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems and extreme problems. The patient is asked to indicate his/her health state by ticking the box next to the most appropriate statement in each of the five dimensions.19 This decision results in a 1-digit number that expresses the level selected for that dimension. The digits for the five dimensions can be combined into a 5-digit number that describes the patient’s health state and can be converted to efficacy score with calibration scale (ranges −0.111 to 1.000).19 The EQ VAS records the patient’s self-rated health on a vertical visual analogue scale, where the endpoints are labelled ‘The best health you can imagine’ and ‘The worst health you can imagine’. The VAS can be used as a quantitative measure of health outcome that reflect the patient’s own judgement.19

Each group will include 44 patients (88 patients in total). Our protocol was approved by PMDA.

Inclusion

Inclusion criteria are as follows: (1) Patients with cervical SCI (severity of AIS B/C) within 48 hours of injury. (2) Patients reassessed for neurological status at 48 hours after injury, and those whose palsy is AIS B/C will be enrolled. (3) Patients with NLI between C4 and C7. (4) Patients with age of 16–85 years. (5) Patients who agree to participate in the current trial and from whom informed consent was obtained orally and in writing. (6) Patients who can be followed up for 12 months after SCI.

Exclusion

Exclusion criteria are as follows: (1) Patients with neurological recovery to AIS D at neurological reassessment 48 hours after SCI, because only AIS B/C patients will be included to standardise the severity of paresis in order to stratify the patients at the initiation of drug administration. (2) Allergy to G-CSF. (3) Haematological malignancy, (4) within 6 months after invasive coronary intervention, (5) splenomegaly or (6) pregnancy, (7) consciousness impairment, (8) neurological disorders that can affect neurological evaluation in the present trial, (9) fracture of extremities that can affect the neurological evaluation and (10) massive dose administration of MPSS. Exclusion criteria 2–6 are set for safety, criteria 1, 7–9 are set to maintain homogeneity of the patient population enrolled, criteria 7–9 are set for maintenance of accuracy of functional assessment, criterion 7 is set to obtain patients’ own informed consent on participation to the trial and criterion 10 is set to omit the possible interference of MPSS on outcome assessment.

Concealment

Patients will be administered drug or placebo and be evaluated in a double-blinded manner. An evaluator blinded to the treatment will take charge of patient evaluation including clinical findings and paresis, without laboratory data because G-CSF induces an apparent increase of white blood cell count that makes it easy to distinguish G-CSF and placebo treatment. Therefore, a non-blinded evaluator for laboratory data will be assigned to evaluate laboratory data alone. From a safety point of view, the dose of G-CSF will be modulated according to excessive increase of white blood cell count. Therefore, a non-blinded evaluator will instruct the pharmacy to modulate the dose of G-CSF based on white blood cell count.

Sample size calculation

The target sample size for this randomised trial is 88. This number is based on the results of previous clinical trials.16 The estimated group difference (±SD) of change in ASIA motor scores from baseline to 3 months is 13.9 (±21.9). A sample size of 44 patients in each group will provide 80% power to detect a difference of the change in ASIA motor scores between the G-CSF and the placebo treatments, using a mixed-effects models for repeated measures (MMRM) at a two-sided 5% level of significance. A common correlation of 0.25 at each time point is assumed. A dropout rate of 10% is allowed. Thus, the total sample size of 88 patients is required for the trial.

Statistical analyses

The analyses of the primary and secondary end points will be performed as intention-to-treat analyses in a full analysis set, which includes all patients who: (1) took at least one course of treatment during the study; (2) do not present any serious violation of the study protocol and (3) have data collected after commencement of treatment. For the baseline characteristics, summary statistics will comprise frequencies and proportions for categorical variables and means and SDs for continuous variables. The patient characteristics will be compared using a χ² test for categorical variables and a t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables. Missing data including loss to follow-up and missing measurement will be supplemented with MMRM.

For the primary analysis, aimed at comparing treatment effects, a change in ASIA motor score from baseline to 3 months and its 95% CI will be estimated using the MMRM. To test for significant association of the primary endpoint, a MMRM with an unstructured covariance matrix will be applied to adjust for age (<65 years or ≥65 years) and AIS at 48 hours after the injury (B or C).

For the secondary analysis, the change in ASIA motor score will be compared using a Student’s t-test and the 95% CI will be estimated. The same method will be applied to change in sensory score, SCIM and EQ-5D. A χ² test will be applied to the frequencies of the responder in AIS and of the improvement in NLI. The frequency of American SPinal INjury Association Impairment Scale (AIS) will be summarised. The frequency of adverse events (AEs) will be compared using a Fisher’s exact test.

All comparisons are planned and all p values will be two sided. P<0.05 will be considered significant. All statistical analyses will be performed using SAS software (V.9.4; SAS, Cary, North Carolina, USA). The statistical analysis plan will be developed by the principal investigator and the biostatistician before completion of patient recruitment and fixing of data.

Data monitoring committee

The data monitoring committee consists of three clinical trial specialists, including a biostatistician, who are independent from the current study. The committee will meet at least two times per year and all the data obtained by the current trial will be checked by the committee.20

Adverse events

As for safety evaluation, adverse events will be collected as follows. ‘Adverse events’ refer to any untoward symptom or disease or signs of such (including clinical laboratory data abnormalities) in a clinical investigation subject after informed consent and does not necessarily have a causal relationship with the investigational product (G-CSF).

Increases in white blood counts will be considered an adverse event only when the count exceeds 50 000/µL from the perspective of a pharmacological effect of G-CSF, and any values below this will not be handled as an adverse event. Anaphylaxis and adult respiratory distress syndrome are the most representative G-CSF-related severe adverse events to be paid full attention.

All adverse events will code terminology used by the investigators according to the ICH International Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities Japanese version (MedDRA/J).

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics

The study will be conducted according to the principles of the World Medical Association (WMA) Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects with the amendments made in Seoul, South Korea, October 2008, with a Note of Clarification on Paragraph 29 added by the WMA General Assembly, Washington 2002; Note of Clarification on Paragraph 30 added by the WMA General Assembly, Tokyo 2004 and in accordance with the Japanese Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO) and other guidelines, regulations and Acts.

Patient informed consent

The principal investigator will try to prepare the informed consent form and other explanatory materials in as simple language as possible in order to obtain informed consent from the patient and the patient’s legal representative. In case that trial participants cannot sign the informed consent form due to upper extremity palsy caused by SCI, allograph by patients’ representative will be allowed.

Public disclosure and publication policy

Results of the clinical study will be submitted to the head of the respective clinical study site as a report after conclusion of the clinical study by the sponsor-investigator (includes study coordinating investigator). Even if the results are not favourable despite conducting the clinical study properly, the data will be published as a paper. Other sponsor-investigators (including the clinical study coordinating investigator), if they plan to publicise the data from this study in a specialised academic society conference or other external site, must first obtain permission from the other principal investigators and investigational product provider. In publicising the results, the confidentiality of the subjects will be maintained and proofread in advance by the other sponsor-investigators (includes coordinating investigator) and investigational product provider.

Discussion

The current trial is a confirmative trial to elucidate the therapeutic efficacy of G-CSF for SCI. If the current trial can successfully show significant improvement of motor paralysis of SCI by G-CSF, we will move forward to drug approval application to the Ministry for Health and Labor, Japan. The entire protocol of the current trial was approved beforehand for the initiation of the current trial by the Japanese PMDA. The PMDA will also permit a drug approval application if significant efficacy of G-CSF for SCI is proven.

The current trial is an important milestone for SCI clinics and research to explore G-CSF for SCI.

Trial status

The present trial is now ongoing.

Trial sites

Nineteen major hospitals in Japan constituting the G-SPIRIT study group are as follows: Tohoku University Hospital, Miyagi; Niigata University, Niigata; Dokkyo University Hospital, Tochigi; Tsukuba University Hospital, Ibaraki; Tsukuba Medical Center, Ibaraki; Chiba University Hospital, Chiba; Funabashi Municipal Medical Center, Chiba; Kimitsu Chuo Hospital, Chiba; Chiba Rosai Hospital, Chiba; Tokai University Hospital, Kanagawa; Hamamatsu University Hospital, Shizuoka; Gifu University Hospital, Gifu; Chubu Rosai Hospital, Aichi; Mie University Hospital, Mie; Kanazawa Medical Collage, Ishikawa; Kobe Red Cross Hospital, Hyogo; Hiroshima University Hospital, Hiroshima; Yamaguchi University Hospital, Yamaguchi and Nagasaki Rosai Hospital, Nagasaki.

bmjopen-2017-019083supp002.jpg (761KB, jpg)

bmjopen-2017-019083supp003.jpg (757KB, jpg)

bmjopen-2017-019083supp004.jpg (550.5KB, jpg)

bmjopen-2017-019083supp005.jpg (397.6KB, jpg)

bmjopen-2017-019083supp006.jpg (295.4KB, jpg)

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors substantially contributed to the conception or design of the present trial protocol, to the acquisition and analyses of data for the present manuscript, to drafting the manuscript and revising the present manuscript critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version of the present manuscript to be published to agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the present manuscript in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the present manuscript are appropriately investigated and resolved, consequently fulfil the ICMJE criteria for authorship.

Funding: This trial is supported by Center for Clinical trials, Japan Medical Association, Japan (http://www.jmacct.med.or.jp/).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Institutional Review Board (IRB) of each institution.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Oyinbo CA. Secondary injury mechanisms in traumatic spinal cord injury: a nugget of this multiply cascade. Acta Neurobiol Exp 2011;71:281–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Karsy M, Hawryluk G. Pharmacologic management of acute spinal cord injury. Neurosurg Clin N Am 2017;28:49–62. 10.1016/j.nec.2016.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Collins WF, et al. . A randomized, controlled trial of methylprednisolone or naloxone in the treatment of acute spinal-cord injury. Results of the Second National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study. N Engl J Med 1990;322:1405–11. 10.1056/NEJM199005173222001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Matsumoto T, Tamaki T, Kawakami M, et al. . Early complications of high-dose methylprednisolone sodium succinate treatment in the follow-up of acute cervical spinal cord injury. Spine 2001;26:426–30. 10.1097/00007632-200102150-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hurlbert RJ, Hadley MN, Walters BC, et al. . Pharmacological therapy for acute spinal cord injury. Neurosurgery 2013;72:93–105. 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31827765c6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nicola NA, Metcalf D, Matsumoto M, et al. . Purification of a factor inducing differentiation in murine myelomonocytic leukemia cells. Identification as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. J Biol Chem 1983;258:9017–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Roberts AW. G-CSF: a key regulator of neutrophil production, but that’s not all!. Growth Factors 2005;23:33–41. 10.1080/08977190500055836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kawada H, Takizawa S, Takanashi T, et al. . Administration of hematopoietic cytokines in the subacute phase after cerebral infarction is effective for functional recovery facilitating proliferation of intrinsic neural stem/progenitor cells and transition of bone marrow-derived neuronal cells. Circulation 2006;113:701–10. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.563668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schneider A, Krüger C, Steigleder T, et al. . The hematopoietic factor G-CSF is a neuronal ligand that counteracts programmed cell death and drives neurogenesis. J Clin Invest 2005;115:2083–98. 10.1172/JCI23559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shyu WC, Lin SZ, Lee CC, et al. . Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor for acute ischemic stroke: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ 2006;174:927–33. 10.1503/cmaj.051322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Koda M, Nishio Y, Kamada T, et al. . Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) mobilizes bone marrow-derived cells into injured spinal cord and promotes functional recovery after compression-induced spinal cord injury in mice. Brain Res 2007;1149:223–31. 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.02.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nishio Y, Koda M, Kamada T, et al. . Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor attenuates neuronal death and promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury in mice. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2007;66:724–31. 10.1097/nen.0b013e3181257176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kadota R, Koda M, Kawabe J, et al. . Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) protects oligodendrocyte and promotes hindlimb functional recovery after spinal cord injury in rats. PLoS One 2012;7:e50391 10.1371/journal.pone.0050391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kawabe J, Koda M, Hashimoto M, et al. . Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) exerts neuroprotective effects via promoting angiogenesis after spinal cord injury in rats. J Neurosurg Spine 2011;15:414–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Takahashi H, Yamazaki M, Okawa A, et al. . Neuroprotective therapy using granulocyte colony-stimulating factor for acute spinal cord injury: a phase I/IIa clinical trial. Eur Spine J 2012;21:2580–7. 10.1007/s00586-012-2213-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Inada T, Takahashi H, Yamazaki M, et al. . Multicenter prospective nonrandomized controlled clinical trial to prove neurotherapeutic effects of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor for acute spinal cord injury: analyses of follow-up cases after at least 1 year. Spine 2014;39:213–9. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kirshblum S, Waring W. Updates for the international standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2014;25:505–17. 10.1016/j.pmr.2014.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fekete C, Eriks-Hoogland I, Baumberger M, et al. . Development and validation of a self-report version of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM III). Spinal Cord 2013;51:40–7. 10.1038/sc.2012.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.https://euroqol.org/eq-5d-instruments/eq-5d-5l-about/

- 20. Aoyagi R, Hamada H, Sato Y, et al. . Study protocol for a phase III multicentre, randomised, open-label, blinded-end point trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of immunoglobulin plus cyclosporin A in patients with severe Kawasaki disease (KAICA Trial). BMJ Open 2015;5:e009562 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-019083supp001.jpg (958.1KB, jpg)

bmjopen-2017-019083supp002.jpg (761KB, jpg)

bmjopen-2017-019083supp003.jpg (757KB, jpg)

bmjopen-2017-019083supp004.jpg (550.5KB, jpg)

bmjopen-2017-019083supp005.jpg (397.6KB, jpg)

bmjopen-2017-019083supp006.jpg (295.4KB, jpg)