Abstract

Introduction:

Studies examining cigarette package pictorial health warning label (HWL) content have primarily used designs that do not allow determination of effectiveness after repeated, naturalistic exposure. This research aimed to determine the predictive and external validity of a pre-market evaluation study of pictorial HWLs.

Methods:

Data were analyzed from: (1) a pre-market convenience sample of 544 adult smokers who participated in field experiments in Mexico City before pictorial HWL implementation (September 2010); and (2) a post-market population-based representative sample of 1765 adult smokers in the Mexican administration of the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Survey after pictorial HWL implementation. Participants in both samples rated six HWLs that appeared on cigarette packs, and also ranked HWLs with four different themes. Mixed effects models were estimated for each sample to assess ratings of relative effectiveness for the six HWLs, and to assess which HWL themes were ranked as the most effective.

Results:

Pre- and post-market data showed similar relative ratings across the six HWLs, with the least and most effective HWLs consistently differentiated from other HWLs. Models predicting rankings of HWL themes in post-market sample indicated: (1) pictorial HWLs were ranked as more effective than text-only HWLs; (2) HWLs with both graphic and “lived experience” content outperformed symbolic content; and, (3) testimonial content significantly outperformed didactic content. Pre-market data showed a similar pattern of results, but with fewer statistically significant findings.

Conclusions:

The study suggests well-designed pre-market studies can have predictive and external validity, helping regulators select HWL content.

Introduction

To inform consumers about tobacco-related risks, the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) recommends tobacco product packaging with prominent, rotating health warning labels (HWL) that include pictorial imagery illustrating the consequences of smoking. 1 To date, over 60 countries have adopted pictorial HWLs 2 but the design of message content varies considerably. To maximize pictorial HWL effects, research is needed on the relative effectiveness of differing HWL content, such as the use of different types of imagery and narrative genres. 3 Some experimental studies have addressed these issues but the predictive and external validity of these studies should be determined to help regulators select the most effective HWLs.

Experimental studies indicate that smokers and youth rate graphic, fear-arousing images on HWLs as more effective than other types of HWL imagery. 4–9 For example, pre-market experimental studies in Mexico and the United States found that HWLs with graphic imagery that shows gruesome diseased body parts were rated as more effective than both lived experience depicting the social and emotional impact of human suffering from smoking-related disease, and symbolic images using abstract representation of the health effects. 8–10 Experiments in Mexico and the United States also indicate that pictorial HWLs with testimonial content focusing on a real personal story work better than HWLs with didactic content, 10 , 11 although this is not always the case, especially among people with higher education. 11

While most studies on pictorial HWL content have primarily used experimental, forced-exposure designs with convenience samples, there is limited research on how results from these studies may predict general population responses under conditions of repeated, naturalistic exposure. In order to meet World Health Organization recommendations for rotating multiple HWLs and regular updating of message content, as well as legal challenges initiated by tobacco industry, regulators need robust data on the external validity of pre-market HWL assessments.

The current study examined the predictive and external validity of a pre-market experimental study to assess the efficacy of different pictorial HWL content in Mexico, where the first round of pictorial HWLs were introduced at the end of 2010. Six HWLs were chosen to appear on the Mexican packs by the Ministry of Health based upon findings from focus groups with smoker and nonsmoker adults and youth. 12 From 2004 until 2010, HWLs covered 50% of the back of the package and included four text-only messages. Thereafter, pictorial HWLs covered 30% of the package front and text only messages covered 100% of the package back, and two different messages were printed on packages every 3 months. Data for the present study were collected before pictorial HWL implementation, and after smokers had been exposed to six different pictorial HWLs implemented on cigarette packs.

Methods

Sample and Recruitment

Data were analyzed from two sources: (1) a pre-market convenience sample of 544 adult smokers aged 19 years or older who participated in field experiments conducted in Mexico City between June 2 and August 7, 2010, before pictorial HWLs were first implemented in September 2010; and (2) a population-based representative sample of 1765 adult smokers aged 18 years or older from seven major Mexican cities who participated in the wave 5 Mexican administration of the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Survey (ITC Mexico) in 2011, approximately 8 to 9 months after pictorial HWL implementation.

Participants in the pre-market sample were selected using standard intercept techniques of approaching every n th person encountered and inviting eligible adult smokers (who had smoked at least one cigarette in the last month) to participate in the study on the spot. 8 A 20-minute computer assisted, interviewer-administered face-to-face survey was conducted using laptop computers. Recruitment sites included two large public parks, a bus terminal, and outside five Walmart stores in Mexico City. Participants in the post-market sample were randomly selected from seven cities (Mexico City, Monterrey, Guadalajara, Puebla, Tijuana, Mérida, and Léon) using a stratified, multistage sampling strategy with face-to-face interviews. 13 Within the urban limits of seven cities, census tracts and then block groups were selected with likelihood of selection proportional to the number of households according to census data. Households were selected in random order and visited up for four times to enumerate household members and recruit eligible adult smokers (who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and smoked at least once a week). The interviewer-administrated pencil and paper survey took an average of 45 minutes to complete.

Procedures

HWL Health Effect and Theme

Participants viewed and rated subsets of HWL images, with each set unified by the health outcome of interest (eg, heart attacks, emphysema). 8 Each set of HWLs that addressed the same health effect included 5 to 7 warnings, with various themes. Images were drawn by authors from actual HWL implemented in several countries and adapted where necessary. These themes included a didactic text-only HWL, and multiple pictorial HWLs with the same didactic text, but with diverse imagery themes (ie, graphic health effects, lived experience, symbolic images); most HWL sets also included a pictorial HWL with testimonial text, and the same pictorial content as one of the lived experience warnings with didactic text. The theme of each pictorial warning was coded by two independent raters, with conflict resolved by a third rater before the study. The themes were defined as follows: (1) Graphic health effects: vivid depiction of physical effects; (2) Lived experience: depiction of personal experience, including social and emotional impact, or implications for quality of life; (3) Symbolic images: representation of message using abstract imagery or symbol; and (4) Testimonial: warnings with a brief narrative describing a personal consequence of smoking, written as a quote from a person in the image, accompanied by their name and age. 8

Rating and Ranking Tasks

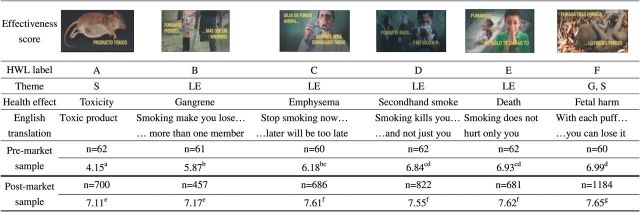

In the pre-market sample, participants were randomized to view 2 of 17 sets of HWLs on a computer screen (see all the HWLs in Hammond et al. 8 ). HWLs within each set were presented in a random order and participants rated each one while the image appeared on screen. The six HWLs that later appeared on Mexican cigarette packs were included in six of the 17 health effect sets (ie, toxicity, gangrene, emphysema, secondhand smoke, death, fetal harm; Table 1 ). After rating each HWL in a set, participants were shown the full set of HWLs (with onscreen position randomized) and asked to rank order them according to which would be most effective for discouraging smoking.

Table 1.

Effectiveness Scores of the Six Health Warning Labels (HWLs) on Mexican Cigarette Packs

Themes: S, symbolic; LE, lived experience; G, graphic. Items used to form the Effectiveness scale showed good internal consistency (α = 0.79–0.90, done for each HWL across samples; five items were whether the HWL: grabbed their attention; was believable; was frightening; would make smokers want to quit; and, overall, how effective they considered the HWL). Effectiveness scores ranged from 1 to 10 (the original scale was 1 to 5 for the post-market sample and was rescaled to 1 to 10).

Superscript letters denote significant difference at P < .05 for all pair wise comparisons of HWL effectiveness scores within the same sample set (a, b, c, d for pre-market sample set; e, f, g for the post-market sample set). HWLs with the same superscript letter are not significantly different from one another. Significance remains the same after adjusting for, sex, age, educational attainment, smoking intensity, and quit intentions.

The authors would like to thank photographer, Pablo Herrerias, for taking the original photos of the cigarette packs in Table 1 and the research team for adapting warning images from other countries.

Participants in the post-market survey were shown laminated cards with images of each of the six HWLs that had appeared on cigarette packs by the date of the interview (in random order), and if they recalled having seen it on cigarette packs, were asked to rate that warning. 14 After rating each of the six HWLs, participants were shown one of seven health effect sets (ie, addiction, aging, impotence, lung cancer, stroke, throat cancer, quitting) that included the same stimuli as the pre-market survey and were then asked to rank order each HWL within the set in the same manner as the pre-market survey. The seven health effect sets were selected because they had more balanced themes compared to other sets. To prevent ordering effects, the arrangement of the HWLs on the laminated card was counterbalanced across interviewers.

Measures

HWL Responses

Ratings

Pre-market sample participants rated each HWL on a scale of 1 to 10 (1 = “not at all”; 10 = “extremely”) for whether the HWL: grabbed their attention; was believable; was frightening; would make smokers want to quit; and, overall, how effective they considered the HWL. Participants in the post-market sample rated HWLs on almost identical measures (ie, questions were posed in the past instead of present tense, and they were asked whether the HWL had made them want to quit) using Likert scales from 1 to 5 (1 = “strongly agree”; 5 = “strongly disagree”). Scores were reverse-coded and rescaled to 1 to 10 for ease of comparison across samples. The five items had high internal consistency across HWLs and samples (alpha range = 0.79–0.90), and were averaged to form a scale with higher scores indicating greater effectiveness.

Rankings

For each health effect set, participants were asked to rank HWLs from the most effective to the least effective, where 1 was the most effective and 7 was the least effective, given 7 HWLs in a set. Ranking data for each HWL was then dichotomized with the most highly-ranked HWL within a set coded as 1 and all other HWLs within that set coded as 0.

Sociodemographics and Smoking Status

Demographic variables included age group (18–24, 25–39, 40–54, 55 and above), sex, and education level (Low = middle school or less, Moderate = high school or technical/vocational school, High = any university). Smoking status included smoking intensity (nondaily smokers, daily smokers who smoked less than 5 cigarettes per day, daily smokers who smoked 5 or more cigarettes per day) and quit intentions (planning to quit smoking within the next 6 months vs. planning to quit sometime in the future or not planning to quit).

Analysis

Unadjusted and adjusted linear mixed effects models were used to test the relative ratings of effectiveness for the six HWLs that appeared on cigarette packs. Unadjusted and adjusted logistic mixed effects models were estimated in which effectiveness rankings served as outcome, and examined which HWL theme was most effective in the six health effects sets that had maximal variation in themes ( Supplementary Appendix 1 ). HWLs that exhibited more than one characteristics (eg, graphic and symbolic in themes), were coded as having both characteristics. Mixed-effect models accounted for repeated measures within individuals, and all models adjusted for sociodemographics (ie, sex age, educational attainment), smoking intensity, and quit intention. Models for theme analyses were also adjusted for health effect set viewed.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Compared to the analytic sample for the post-market study ( n = 1529 for ratings analysis; n = 1427 for ranking analysis; see Supplementary Appendix 2 ), the analytic sample for the pre-market study ( n = 335 for ratings analysis; n = 309 for ranking analysis) included a lower proportion of: males (ratings = 50% vs. 64%; ranking = 48% vs. 64%), older people (ratings = 29 vs. 39 years old; ranking = 28 vs. 39 years old), people with low or moderate educational attainment (ratings = 60% vs. 86%; ranking = 61% vs. 87%), daily smokers (ratings = 54% vs. 74%; ranking = 51% vs. 72%), and people without quit intention (ratings = 75% vs. 85%; ranking = 75% vs. 86%).

HWL Ratings

Pre- and post-market data showed similar relative ratings across the six HWLs that appeared on cigarette packs, with the least and most effective HWLs consistently differentiated from other HWLs ( Table 1 ). The HWL (Label F) that depicted both graphic and symbolic themes showing a fetus surrounded by cigarette butts was rated as the most effective HWL in both pre-market and post-market samples, but was significantly different from the next most effective HWL (Label E) using a lived experience theme only in the post-market sample. The HWL (Label A) describing toxic tobacco constituents including a deadly poison used to kill rats, coded as a symbolic theme, was rated as the least effective HWL in both samples, but was significantly different from the next least effective HWL (Label B) with a lived experience theme only in the pre-market sample. The other three lived experience HWLs (Labels C, D, and E) had similar effectiveness scores in both samples. However, these three lived experience HWLs were rated significantly differently from the other HWLs (Labels A, B and F) in the post-market sample, but were not completely discernible from the other HWLs (Labels B and F) in the pre-market sample.

HWL Ranking of Themes

Table 2 shows estimates from three models in which ranking as “most effective” within a health effect set served as the outcome and HWL themes as the predictors. The first model, comparing text-only HWLs with pictorial HWLs with the same text, indicated a significantly greater likelihood of pictorial HWLs being ranked as most effective in both samples. The second set of models compared different pictorial HWL themes, and pre- and post-market results showed a similar pattern: graphic and lived experience content (alone or combined) were more likely to be ranked as more effective than symbolic content. However, this pattern was statistically significant only in the post-market sample. In the pre-market sample, statistical significance was reached only for HWLs with graphic content compared to symbolic content in the unadjusted model, and when graphic and lived experience were combined in both unadjusted and adjusted models. The third set of models compared pictorial HWLs with testimonial text to the HWLs that shared the same imagery but used standard didactic text. The results indicated that testimonial content was ranked as significantly more effective than didactic content for the post-market sample ( AOR 2.64, 95% CI = 2.27, 3.08), with no statistically significant result for the pre-market sample.

Table 2.

Relative Effectiveness of Health Warning Label Themes

| Sample | Theme | n | Probability a | Odd ratios (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted b | ||||

| Pre-market | Text-only | 67 | .18 | 1 | 1 |

| Pictorial | 294 | .23 | 1.33 (1.00, 1.78)* | 1.33 (1.00, 1.78)* | |

| Symbolic | 109 | .25 | 1 | 1 | |

| Lived experience | 90 | .29 | 1.38 (0.96, 1.98) | 1.33 (0.92, 1.93) | |

| Graphic | 126 | .3 | 1.42 (1.01, 1.99)* | 1.36 (0.96, 1.93) | |

| Graph with lived experience | 76 | .32 | 1.53 (1.05, 2.24)* | 1.53 (1.04, 2.23)* | |

| Didactic | 178 | .49 | 1 | 1 | |

| Testimonial | 185 | .51 | 1.08 (0.81, 1.45) | 1.07 (0.80, 1.43) | |

| Post-market | Text-only | 67 | .05 | 1 | 1 |

| Pictorial | 1358 | .27 | 7.69 (5.97, 9.90)*** | 7.84 (6.07, 10.11)*** | |

| Symbolic | 439 | .27 | 1 | 1 | |

| Lived experience | 400 | .31 | 2.22 (1.83, 2.70)*** | 2.22 (1.81, 2.72)*** | |

| Graphic | 627 | .33 | 2.42 (2.02, 2.91)*** | 2.44 (2.02, 2.95)*** | |

| Graph with lived experience | 206 | .32 | 2.32 (1.85, 2.91)*** | 2.29 (1.81, 2.90)*** | |

| Didactic | 538 | .38 | 1 | 1 | |

| Testimonial | 881 | .62 | 2.68 (2.30, 3.12)*** | 2.64 (2.27, 3.08)*** | |

CI = confidence interval.

a Probability of being ranked as most effective.

b Models were adjusted for sex, age, educational attainment, health effect, smoking intensity, and quit intentions.

Significance levels: * P < .05; ** P < .01; *** P < .001.

Discussion

Smokers’ evaluations of the six HWLs that were included in the first round of pictorial HWLs were generally consistent across pre- and post-market studies, suggesting the predictive and external validity of the pre-market study. Pre-market study results for HWL themes found statistically significant differences between HWL stimuli only when comparing symbolic content and graphic content combined with lived experience content. Nevertheless, the directionality of pre-market study results was similar to the post-market study and consistent with results from the larger parent pre-market study 8 which had more variation in stimuli (17 health topics), included a rating scale, and had a larger sample size and statistical power to determine effects.

The findings from our post-market study provide additional evidence for the superiority of pictorial versus text-only HWLs, but also highlighted the increased effectiveness of adding testimonial content to pictorial HWLs more than didactic contents. 15 Testimonial content may be more effective than didactic content because it is enhances emotional arousal. 15 , 16 HWLs that employed symbolic representations were perceived as less effective than other pictorial themes, perhaps because abstract depictions are less well understood or because they elicit weaker emotional responses. Furthermore, certain health effects may be more amenable to depiction through particular themes (eg, symbolic images illustrating addiction or quitting; graphic and lived experience images illustrating cancer and disease), as with antismoking advertisements. 17 While it appears that HWL imagery that combines graphic imagery and lived experiences is most powerful, more research is needed on how best to communicate about other health topics, such as cessation advice.

Limitations of this study include the modest sample size for the pre-market study, variations in range and item wording of rating scales between the pre-market and post-market studies, and timing issues of the pre-market and post-market studies. For example, the difference in the ranges of the scales used in the studies (ie, rescaling from 1–5 to 1–10) may have resulted in a narrower range in the post-market ratings, making direct comparisons in ratings between the two samples challenging. The timing of the pre-market and post-market studies could have affected our outcome measures and analytic sample size for the six HWL on the Mexican cigarette packs. It is possible that the timing of pre-market study 3 months before HWL implementation meant that some participants had previously viewed the HWLs because of media coverage of the new HWLs. However, it seems unlikely that a study conducted considerably earlier than policy implementation would produce different results. In the period before implementation of pictorial HWLs, which were just one part of a comprehensive tobacco control law, media attention to tobacco was focused more on economic issues and smoke-free policies. 18 There was no coordinated media outreach during the runup to implementation, and informal monitoring of media suggested that coverage remained null to low during the study period. Furthermore, the implementation date was for printing of the HWLs, not for their appearance in stores, which can take up to 6 months from the print date. Hence, we do not think we would have found different results if the pre-market study had been conducted earlier. The substantially different sample size of post-market study for each HWL was likely affected by the timing of the six HWL introduced in Mexico and the post-market assessment. For example, one HWL (Label F) was recalled by many more participants than other HWLs. This HWL was one of the first two to appear on market, so it was more likely to be recalled due to longer period of exposure. Furthermore, future validation research in this area should involve more comparable samples and ensure adequate power for examining key hypotheses. Nevertheless, this research represents a unique advance due to sharing of protocols across pre- and post-implementation samples, including a population-based representative sample of smokers in the post-market survey.

In conclusion, this study suggests that well-designed pre-market studies can have predictive and external validity, and may be used to assist regulators in making evidence-based decisions about the selection of HWL content. The pre- and post-implementation design provides a model to systematically test and evaluate the most effective message themes for the general public or particular target groups.

Funding

Data collection and analyses for this project were supported by grants from the US National Cancer Institute (P01 CA138389 and R01 CA167067), the Mexican National Council on Science and Technology (Salud-2007-C01-70032) and also by the Propel Centre for Population Health Impact, a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Award, and the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute Junior Investigator Award (awarded to DH). The funding sources had no role in the study design, in collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Declaration of Interests

None declared .

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Códice Comunicación Diálogo y Conciencia SC and Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública (INSP) for their assistance in conducting this work, and to acknowledge the assistance of Ana Dorantes (field manager for Mexico) and Samantha Daniel.

References

- 1. World Health Organization . WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control . Geneva, Switzerland: : World Health Organization; ; 2013. . [Google Scholar]

- 2. Canadian Cancer Society . Cigarette Package Health Warnings: International Status Report . 3 rd ed. Toronto, ON, Canada: : Canadian Cancer Society; ; 2012. . [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hammond D, Wakefield M, Durkin S, Brennan E . Tobacco packaging and mass media campaigns: research needs for articles 11 and 12 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control . Nicotine Tob Res . 2012. ; 15 ( 4 ): 817 – 831 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Elliott & Shanahan Research . Developmental Research for New Australian Health Warnings on Tobacco Products Stage 2. Prepared for the Australian Population Health Division Department of Health and Aging. Commonwealth of Australia . Sydney, Australia: : Elliott & Shanahan Research; ; 2003. . [Google Scholar]

- 5. BRC Marketing & Social Research . Smoking Health Warnings. Stage 1: The Effectiveness of Different (Pictorial) Health Warnings in Helping People Consider Their Smoking-Related Behavior. Prepared for the New Zealand Ministry of Health . Wellington, New Zealand: : BRC Marketing & Social Research; ; 2004. . [Google Scholar]

- 6. Les Etudes de Marche Createc . Final Report: Qualitative Testing of Health Warnings Messages. Prepared for the Tobacco Control Programme Health Canada . Montreal, QC, Canada: : Les Etudes de Marche Createc; ; 2006. . [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thrasher JF, Allen B, Anaya-Ocampo R, Reynales LM, Lazcano-Ponce EC, Hernandez-Avila M . Analysis of the impact of cigarette package warning labels with graphic images among Mexican smokers . Salud Publica Mex . 2006. ; 48 ( suppl 1 ): S65 – S75 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hammond D, Thrasher JF, Reid J, Driezen P, Boudreau C, Santillan EA . Perceived effectiveness of pictorial health warnings among Mexican youth and adults: a population-level intervention with potential to reduce tobacco-related inequities . Cancer Causes Control . 2012. ; 23 ( suppl 1 ): 57 – 67 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cameron D, Pepper JK, Brewer NT . Responses of young adults to graphic warning labels for cigarette packages [published online ahead of print April 26, 2013]. Tob Control . doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050645 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thrasher JF, Arillo-Santillán E, Villalobos V, et al. . Can pictorial warning labels on cigarette packages address smoking-related health disparities? Field experiments in Mexico to assess pictorial warning label content . Cancer Causes Control . 2012. ; 23 ( suppl 1 ): 69 – 80 . doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9899-8 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hammond D, Reid J, Driezen P, Boudreau C . Pictorial health warnings on cigarette packs in the United States: an experimental evaluation of the proposed FDA warnings . Nicotine Tob Res . 2013. ; 15 ( 1 ): 93 – 102 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Justino Regalado-Pineda J, Madrazo-Reynoso M. Adopción de advertencies sanitarias y su implementación: el caso de México. In: Thrasher JF, Reynales-Shigematsu LM, Lazcano-Ponce E, Hernández-Ávila M , eds. Salud pública y tabaquismo, Volumen II. Advertencias sanitarias en América Latina y el Caribe [Public Health & Tobacco, Volume 2: Warning Labels in Latin America and the Caribbean] . Cuernavaca, México: : Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública; ; 2013. : 39 – 59 . [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thrasher JF, Boado M, Sebrie EM, Bianco E . Smoke-free policies and the social acceptability of smoking in Uruguay and Mexico: findings from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project . Nicotine Tob Res . 2009. ; 11 ( 6 ): 591 – 599 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thrasher JF, Pérez-Hernández R, Arillo-Santillán E, Barrientos-Gutierrez I . Hacia el consumo informado de tabaco en México: Efecto de las advertencias en población fumadora [Towards informed tobacco consumption in Mexico: Effects of pictorial warning labels among smokers] . Revista de Salud Pública de México . 2012. ; 54 ( 3 ): 242 – 253 . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Western Opinion/NRG Research Group . Illustration-Based Health Information Messages: Concept Testing. Prepared for Health Canada . Montreal, QC, Canada: : Western Opinion/NRG Research Group; ; 2006. . [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kreuter MW, Green MC, Cappella JN, et al. Narrative communication in cancer prevention and control: a framework to guide research and application . Ann Behav Med . 2007. ; 33 ( 3 ): 221 – 235 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. National Cancer Institute . Overview of media interventions in tobacco control . In: Davis RM, Gilpin EA, Loken B, Viswanath K, Wakefield MA, eds. The Role of Media in Promoting and Reducing Tobacco Use . Bethesda, MD: : Tobacco Control. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Health, National Cancer Institute; ; 2008. : 449 – 459 . [Google Scholar]

- 18. Llaguno-Aguilar SE, Dorantes-Alonso AC, Thrasher JF, Villalobos V, Besley JC . Análisis de la cobertura del tema de tabaco en medios impresos mexicanos. [Analysis of the coverage of tobacco in Mexican print media] . Salud Pública de México . 2008. : 30 ( suppl 3 ); S348 – S354 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.