Dear Editor,

Incidence of tachyarrhythmias may increase during pregnancy, possibly due to the physiological changes associated with pregnancy. Though atrial fibrillation is the most common arrhythmia, its incidence in pregnancy is rare and if present it usually occurs in patients with congenital heart disease, rheumatic heart disease and other noncardiac conditions such as thyroid and electrolyte abnormalities, medication effects (such as tocolytics) and pulmonary embolism [Walsh et al. 2008]. New-onset lone atrial fibrillation in pregnancy is extremely rare and here we report a case of a young pregnant female presented with lone atrial fibrillation without hemodynamic compromise who responded well to intravenous diltiazem.

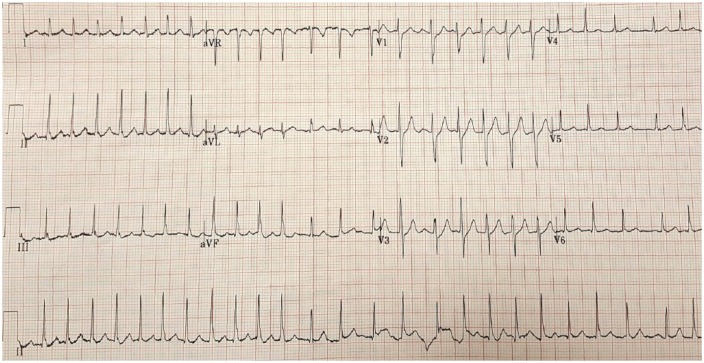

A 30-year-old woman who was 34 weeks pregnant (gravida 3, para 0-0-2-0) referred from labor and delivery to the emergency room (ER) with acute onset dyspnea, palpitations and chest tightness for 2 hours. The patient did not have any medical problems prior to presentation nor any prior history of similar symptoms. The patient was not taking any medications except prenatal vitamins, and denied any alcohol use. In the ER, the patient was found to have a rapid heart rate of 160–170 bpm with an irregularly irregular pulse, but the patient was hemodynamically stable with a blood pressure of 110/57 mmHg. A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) of the patient showed atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response (ventricular rate = 160) (Figure 1). The patient was given one dose of intravenous (IV) diltiazem (10 mg) and was started on diltiazem infusion at a rate of 5 mg/h, after which the patient’s heart rate was controlled, eventually converting to normal sinus rhythm. The patient was admitted to the telemetry floor and was monitored by cardiology and by obstetrics and gynecology (OB/GYN) clinicians. Subsequent testing showed normal electrolytes, thyroid profile and transthoracic echocardiogram and a negative drug screen. The patient remained in normal sinus rhythm and was discharged to home on the second hospital day with no anticoagulation. The patient was instructed to follow up with cardiology as an outpatient after the delivery.

Figure 1.

A 12-lead electrocardiogram of the patient showing atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response.

New-onset lone atrial fibrillation in pregnancy is extremely rare with very few cases reported until now [Gowda et al. 2003; Kuczkowski, 2004; Walsh et al. 2008; DiCarlo-Meacham and Dahlke, 2011]. Diagnosis of lone atrial fibrillation in pregnancy requires exclusion of underlying cardiopulmonary disease. Initial work up should include a 12-lead ECG, serum electrolytes, a thyroid profile, a drug screen and a transthoracic echocardiogram. Treatment of atrial fibrillation in pregnancy is challenging because of the teratogenicity of the medications. Rate control is the initial goal of treatment. Digoxin, beta blockers and nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers can be used as initial treatment in pregnant patients. Digoxin use can be problematic due to altered serum levels during pregnancy. If severe symptoms persist despite rate-controlling medications, prophylactic antiarrhythmic drugs such as sotalol, flecainide or propafenone may be considered. In hemodynamically unstable patients, direct-current (DC) cardioversion should be considered. Pharmacological cardioversion should be considered in hemodynamically stable patients with structurally normal hearts. Intravenous flecainide or ibutilide may be considered for cardioversion, but evidence regarding these agents is limited. Anticoagulation should be considered in all patients except in patients with lone atrial fibrillation and/or low thromboembolic risk. The choice of anticoagulant depends on the stage of pregnancy. Heparin is preferred in pregnancy as it does not cross the placenta and should be considered for use in the first trimester and also in the last month of pregnancy. Warfarin is generally avoided during pregnancy as it does cross the placenta and is associated with teratogenic effects in first trimester and fetal hemorrhage if used in the later stages of pregnancy. Warfarin may be considered in the second trimester until 1 month before the expected delivery in patients with high thromboembolic risk. Elective cardioversion of atrial fibrillation (pharmacological or electrical) requires prior anticoagulation for 3 weeks if the episode lasted for more than 48 hours or was of unknown duration and/or a transesophageal echocardiogram is considered to rule out intracardiac thrombus prior to cardioversion. Anticoagulation should be continued at least for 4 weeks after cardioversion in those patients [Fuster et al. 2006; Regitz-Zagrosek et al. 2011]. The new direct oral anticoagulants such as dabigatran, rivaroxaban and apixaban are not used in pregnancy due to a lack of data on efficacy and fetal safety [Bates et al. 2012].

Our patient did not have any underlying comorbidities and the atrial fibrillation episode resolved in less than 48 hours so the patient was discharged with no anticoagulation. Atrial fibrillation in pregnancy is rare and can lead to fatal hemodynamic compromise and clinicians should be aware of appropriate management choices in those situations.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in preparing this letter.

Contributor Information

Viswajit Reddy Anugu, Staten Island University Hospital, 475 Seaview Avenue, Staten Island, NY 10305, USA.

Nikhil Nalluri, Staten Island University Hospital, Staten Island, NY, USA.

Deepak Asti, Staten Island University Hospital, Staten Island, NY, USA.

Sainath Gaddam, Staten Island University Hospital, Staten Island, NY, USA.

Thomas Vazzana, Staten Island University Hospital, Staten Island, NY, USA.

James Lafferty, Staten Island University Hospital, Staten Island, NY, USA.

References

- Bates S., Greer I., Middeldorp S., Veenstra D., Prabulos A., Vandvik P. (2012) VTE, thrombophilia, antithrombotic therapy, and pregnancy: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 141(2 Suppl.): e691S–e736S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiCarlo-Meacham A., Dahlke J. (2011) Atrial fibrillation in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 117: 489–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuster V., Ryden L., Cannom D., Crijns H., Curtis A., Ellenbogen K., et al. (2006) ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 114: e257–e354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowda R., Punukollu G., Khan I., Wilbur S., Navarro V., Vasavada B., et al. (2003) Lone atrial fibrillation during pregnancy. Int J Cardiol 1: 123–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczkowski K. (2004) New onset transient lone atrial fibrillation in a healthy parturient: déjà vu. Int J Cardiol 2: 339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regitz-Zagrosek V., Blomstrom Lundqvist C., Borghi C., Cifkova R., Ferreira R., Foidart J., et al. (2011) ESC Guidelines on the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy: the Task Force on the Management of Cardiovascular Diseases during Pregnancy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 32: 3147–3197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh C., Manias T., Patient C. (2008) Atrial fibrillation in pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1: 119–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]