Summary

Background

Abortion can help women to control their fertility and is an important component of health care for women. Although women in the USA who live further from an abortion clinic are less likely to obtain an abortion than women who live closer to an abortion clinic, no national study has examined inequality in access to abortion and whether inequality has increased as the number of abortion clinics has declined.

Methods

For this analysis, we obtained data on abortion clinics for 2000, 2011, and 2014 from the Guttmacher Institute’s Abortion Provider Census. Block groups and the percentage of women aged 15–44 years by census tract were obtained from the US Census Bureau. Distance to the nearest clinic was calculated for the population-weighted centroid of every block group. We calculated the median distance to an abortion clinic for women in each county and the median and 80th percentile distances for each state by weighting block groups by the number of women of reproductive age (15–44 years).

Findings

In 2014, women in the USA would have had to travel a median distance of 10·79 miles (17·36 km) to reach the nearest abortion clinic, although 20% of women would have had to travel 42·54 miles (68·46 km) or more. We found substantially greater variation within than between states because, even in mostly rural states, women and clinics were concentrated in urban areas. We identified spatial disparities in abortion access, which were broadly unchanged, at least as far back as 2000.

Interpretation

We showed substantial and persistent spatial disparities in access to abortion in the USA. These results contribute to an emerging literature documenting similar disparities in other high-income countries.

Funding

An anonymous grant to the Guttmacher Institute.

Introduction

Induced abortion allows women to control their fertility, and ensuring that all women in the USA have access to abortion is a public health goal.1,2 In 2011, 2·8 million (45%) of the 6·1 million pregnancies in the USA were unintended, and 42% of unintended pregnancies ended in abortion.3 However, abortion is not always easy to access in the USA, and issues such as stigma, restrictive laws, and financial constraints can pose barriers to access. One key measure of access is how far women have to travel to reach an abortion clinic. Previous research4–7 found that the further a woman lives from a provider, the less likely she is to obtain an abortion. Most patients seeking an abortion have limited financial resources, so having to cover the cost of travel (which can include overnight stays and time off work) might prevent them from having an abortion.8

Spatial inequality—unequal access to resources and services based on location—affects access to abortion in many countries where it is legal.9 Studies10–13 in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the USA have found that, among women who have abortions, those who live in rural areas typically travel greater distances than those who live in urban areas, at least in part because of subnational variation in restrictive laws.13

At least 20 US states have adopted one or more abortion restrictions since 2011 (appendix), making analysis of spatial inequality in that country particularly timely and relevant.14 In 2008, patients in the USA travelled a median distance of 15 miles (24 km) to have an abortion.15 Although the median distance travelled was reasonably low, a substantial minority of women (17%) travelled 50 miles (80 km) or more, and 31% of women living in rural areas travelled 100 miles (161 km) or more to have an abortion. A 2016 study16 examined the change in how far women travelled for an abortion in the state of Texas after implementation of a restrictive law, which resulted in the closure of 22 (54%) of 41 abortion providers in the state. Similar to women nationally, patients in Texas in 2013 travelled a mean distance of 15 miles (24 km) to reach an abortion facility. The mean distance increased by 20 miles (32 km), to 35 miles (56 km), in 2014 after the law came into effect, and the number of patients who travelled more than 50 miles (80 km) increased from 10% to 44%.16

A limitation of those analyses was that they examined users of abortion services and did not capture women who wanted abortions but did not make it to the clinic because of distance; thus, they did not fully capture spatial inequality in access to abortions.4–7 Two studies4,7 found that the number of abortions in a county in Texas decreased as the distance to the nearest abortion facility increased between 2012 and 2014. Previous studies5,6 that used abortion data for the states of New York and Georgia in the 1970s also found that the further women lived from a county or state where abortion care was provided, the lower the abortion incidence. These studies suggest that distance has been a persistent barrier to abortion.

Between 2011 and 2014, abortion incidence in the USA decreased by 14% to 14·6 abortions per 1000 women (15–44 years) each year.17 During the same period, the number of clinics providing abortions decreased by 6%, from 839 to 788, compared with a 1% decline across the preceding 3 year period.17 The decline in clinics was greatest in the midwest (22%) and southern (13%) regions, which also had the highest number of abortion restrictions enacted over this period.17 As abortion clinics closed and service availability shifted, women might have had to travel further to have an abortion.

Using abortion-clinic data for 2014, 2011, and 2000, we examined spatial disparities in distance to the nearest abortion clinic by state and county. Because a decline in the number of abortion clinics might have increased the distance women had to travel to reach a provider,17 we also examined state-specific and county-specific changes in distance to abortion clinics between 2011 and 2014. In a supplementary analysis to assess the long-term stability of access to abortion, we also analysed change since 2000.

Methods

Study design

We obtained the location of all abortion clinics in the USA from the Guttmacher Institute’s Abortion Provider Census (APC). Since 1973, the Guttmacher Institute has regularly surveyed all known abortion-providing facilities to collect information about number of abortions and other aspects of service provision. The APC provides the most accurate counts of abortion available in the USA.18 In the most recent APC, information was collected for 2014.17 We also used data for 2011 and 2000 in this analysis. Approval for the study was obtained through expedited review by the Guttmacher Institute’s federally registered institutional review board.

To identify clinics providing abortion services to the public, we limited the analysis to facilities that had caseloads of 400 abortions or more per year and those affiliated with Planned Parenthood that did at least one abortion in the period of interest. We included Planned Parenthood facilities that provided fewer than 400 abortions in a year because of name recognition and because their websites indicated whether they provided abortion services. These providers did 95% of all abortions in 2014; of the remainder, 2·1% occurred in hospitals, 1·4% in private physicians’ offices, and 1·5% in health clinics.

Not all locations where abortions are done are accessible and discoverable to a woman seeking abortion care. Abortion providers in the USA have been targets of domestic terrorism, and doctors might be unable to maintain a practice if they are known to be willing to do abortions. Our data collection efforts showed that facilities doing small numbers of abortions seldom advertise their services. Thus, it is possible for a woman to live near to an abortion provider without knowing of that physician or that the physician provides abortions. Such a provider would not constitute a public point of access, and these were excluded from our analysis. Moreover, confidentiality concerns did not allow us to reveal the locations of low-volume providers because doing so would threaten their safety.

Statistical analysis

To measure the distance between women and abortion providers, we first needed to specify the location of both. For women, we used the smallest publicly available geographical units, census block groups, which are geographical subdivisions of census tracts.19 For their coordinates, we used population-weighted centroids.20 For abortion providers, we geocoded (ie, determined the latitude and longitude of) each provider using Maptitude 2016, and linked each census block group to the nearest provider. Some women obtain abortions outside their state of residence; as such, in our analysis the nearest provider could be in another county or state. We used Open Source Routing Machine 4.9 to compute driving distance.21

To estimate mean and percentile distances for each state and county, we weighted each block group by the approximate number of women of reproductive age (15–44 years). We obtained population data for 2000 and 2010 from the Decennial Census.22,23 The smallest geographical area for which age and sex distributions were available was census tract; therefore, we multiplied each block group’s population by the proportion of the census tract that was made up of women aged 15–44 years. To account for population growth after 2010, the last year a census was done, we scaled each block group’s population using the Census Bureau’s 2011 and 2014 county population estimates.24

Mean distances were right skewed by the small proportion of women who lived several 100 miles from the nearest provider. For this reason, we used median distance or the value for which half of women in a county lived from the nearest provider. In our state-level analyses, we also examined 80th percentile distances.

We analysed whether distance to provider varied by the National Center for Health Statistics’ urban-rural classification scheme, an extension of the Office of Management and Budget metropolitan statistical area (MSA) classification.25

No smooth gradient was seen in the number of abortions done by providers; of the providers excluded from the analysis in 2014, 631 (62%) did fewer than 25 abortions, whereas 38 (4%) did 300–399 abortions. A concern was that a small number of abortions might have placed a provider above or below 400 abortions so as to substantively affect our results. To address this possibility, we did a sensitivity analysis that included all providers who did at least 200 abortions.

Another concern was that rural areas might have been served by providers who did very few abortions. However, although 43% of counties were rural, less than 1% of the excluded providers were in rural areas. All of these were either hospitals or physicians’ offices, except for one clinic, which did not advertise abortion services on its website.

We excluded the District of Columbia from the tables and discussion of the findings (but not from the overall analysis) because it is not a state. In both 2011 and 2014, the District of Columbia had four or more abortion clinics,17,26 and residents would have had to travel a median distance of 2 miles to reach the nearest clinic (shorter than the median distance in any state).

Role of the funding source

The funding source did not have any role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Nationally, half of all women of reproductive age in 2014 lived within 10·79 miles (17·36 km) of an abortion clinic (table). The median distance a woman would have had to travel to reach the nearest abortion clinic in 2014 was less than 15 miles (24 km) in 23 (46%) states (figure 1 and table). These states were located in all four geographical regions. Because we considered the concentration of residents in census block groups, many women in states with large rural populations would not have had to travel far to reach a clinic. For example, although a third of residents in Alaska live in rural areas,27 we found that half of all women in this state lived within 9·31 miles (14·98 km) of the nearest abortion clinic.

Table.

Median and 80th percentile distances to nearest abortion clinic for women aged 15–44 years in 2011–14, by state

| 2011 | 2014 | Change in distance, 2011–14 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Median | 80th percentile | Median | 80th percentile | Median | 80th percentile | |

| USA | 10·59 (17·04) | 40·26 (64·80) | 10·79 (17·36) | 42·54 (68·46) | 0·20 (0·32) | 2·28 (3·66) |

|

| ||||||

| Northeast | ||||||

| Connecticut | 5·74 (9·24) | 10·65 (17·13) | 5·17 (8·32) | 9·70 (15·60) | –0·57 (–0·92) | –0·95 (–1·53) |

| Maine | 46·12 (74·22) | 129·73 (208·77) | 25·31 (40·73) | 40·36 (64·95) | –20·81 (–33·49) | –89·37 (–143·82) |

| Massachusetts | 9·67 (15·56) | 21·64 (34·82) | 9·77 (15·72) | 21·52 (34·63) | 0·10 (0·16) | –0·12 (–0·19) |

| New Hampshire | 15·08 (24·27) | 24·28 (39·07) | 14·98 (24·10) | 24·14 (38·84) | –0·10 (–0·16) | –0·14 (–0·23) |

| New Jersey | 6·70 (10·78) | 14·37 (23·12) | 5·43 (8·74) | 11·65 (18·75) | –1·27 (–2·04) | –2·72 (–4·37) |

| New York | 3·19 (5·14) | 9·66 (15·55) | 3·17 (5·10) | 9·12 (14·67) | 0·03 (–0·04) | –0·54 (–0·87) |

| Pennsylvania | 12·96 (20·86) | 51·92 (83·55) | 13·00 (20·91) | 50·92 (81·95) | 0·04 (0·06) | –0·99 (–1·60) |

| Rhode Island | 7·07 (11·38) | 18·90 (30·41) | 7·07 (11·38) | 18·83 (30·31) | 0·00 (0·00) | –0·07 (–0·11) |

| Vermont | 18·86 (30·36) | 34·98 (56·29) | 15·78 (25·40) | 34·08 (54·84) | –3·08 (–4·96) | –0·90 (–1·45) |

|

| ||||||

| Midwest | ||||||

| Illinois | 9·96 (16·03) | 29·56 (47·57) | 10·41 (16·75) | 32·67 (52·58) | 0·45 (0·72) | 3·11 (5·01) |

| Indiana | 21·34 (34·34) | 60·51 (97·37) | 21·32 (34·31) | 60·30 (97·04) | –0·02 (–0·03) | –0·21 (–0·34) |

| Iowa | 17·61 (28·33) | 47·76 (76·87) | 12·16 (19·57) | 47·92 (77·12) | –5·45 (–8·77) | 0·16 (0·25) |

| Kansas | 105·58 (169·92) | 188·93 (304·05) | 32·04 (51·57) | 100·50 (161·74) | –73·54 (–118·35) | –88·43 (–142·31) |

| Michigan | 10·92 (17·57) | 35·35 (56·89) | 12·63 (20·33) | 42·85 (68·96) | 1·71 (2·76) | 7·50 (12·07) |

| Minnesota | 16·47 (26·50) | 60·43 (97·25) | 17·77 (28·59) | 60·55 (97·44) | 1·30 (2·09) | 0·12 (0·20) |

| Missouri | 29·54 (47·54) | 97·62 (157·10) | 36·99 (59·53) | 124·38 (200·17) | 7·45 (11·99) | 26·76 (43·07) |

| Nebraska | 9·21 (14·82) | 97·16 (156·36) | 9·36 (15·06) | 98·13 (157·92) | 0·15 (0·24) | 0·97 (1·56) |

| North Dakota | 137·13 (220·68) | 284·23 (457·42) | 151·58 (243·94) | 286·78 (461·52) | 14·46 (23·27) | 2·55 (4·11) |

| Ohio | 16·43 (26·44) | 45·26 (72·83) | 15·41 (24·80) | 45·58 (73·36) | –1·02 (–1·64) | 0·33 (0·53) |

| South Dakota | 95·87 (154·29) | 327·33 (526·79) | 92·06 (148·16) | 329·85 (530·83) | –3·81 (–6·14) | 2·51 (4·04) |

| Wisconsin | 29·18 (46·96) | 66·82 (107·53) | 29·53 (47·53) | 64·78 (104·25) | 0·35 (0·56) | –2·04 (–3·28) |

|

| ||||||

| South | ||||||

| Alabama | 26·59 (42·80) | 60·91 (98·03) | 26·20 (42·16) | 60·01 (96·58) | –0·40 (–0·64) | –0·90 (–1·45) |

| Arkansas | 49·29 (79·32) | 82·10 (132·13) | 48·35 (77·81) | 81·63 (131·36) | –0·94 (–1·51) | –0·47 (–0·76) |

| Delaware | 6·65 (10·71) | 19·36 (31·15) | 6·68 (10·75) | 19·39 (31·20) | 0·03 (0·04) | 0·03 (0·05) |

| Florida | 8·34 (13·42) | 22·58 (36·33) | 7·84 (12·62) | 20·74 (33·38) | –0·50 (–0·80) | –1·84 (–2·95) |

| Georgia | 20·11 (32·37) | 63·05 (101·47) | 17·95 (28·89) | 59·94 (96·46) | –2·16 (–3·48) | –3·11 (–5·01) |

| Kentucky | 38·88 (62·57) | 91·24 (146·83) | 38·18 (61·45) | 90·51 (145·66) | –0·70 (–1·13) | –0·73 (–1·17) |

| Louisiana | 34·39 (55·34) | 75·34 (121·24) | 35·06 (56·42) | 84·81 (136·48) | 0·67 (1·07) | 9·47 (15·24) |

| Maryland | 5·86 (9·42) | 15·53 (24·99) | 6·20 (9·97) | 16·61 (26·73) | 0·34 (0·55) | 1·08 (1·74) |

| Mississippi | 68·31 (109·94) | 95·30 (153·37) | 68·80 (110·72) | 94·92 (152·76) | 0·49 (0·78) | –0·38 (–0·61) |

| North Carolina | 19·07 (30·69) | 46·41 (74·68) | 18·34 (29·52) | 45·68 (73·52) | –0·73 (–1·17) | –0·72 (–1·16) |

| Oklahoma | 21·47 (34·55) | 75·59 (121·65) | 20·79 (33·46) | 75·09 (120·84) | –0·68 (–1·09) | –0·50 (–0·81) |

| South Carolina | 24·24 (39·01) | 52·05 (83·76) | 23·98 (38·59) | 51·71 (83·23) | –0·26 (–0·42) | –0·33 (–0·54) |

| Tennessee | 26·99 (43·43) | 68·50 (110·23) | 26·91 (43·31) | 68·54 (110·30) | –0·08 (–0·13) | 0·04 (0·06) |

| Texas | 14·01 (22·55) | 32·86 (52·88) | 17·23 (27·72) | 89·36 (143·81) | 3·22 (5·18) | 56·50 (90·93) |

| Virginia | 10·91 (17·56) | 40·22 (64·73) | 11·25 (18·10) | 39·67 (63·85) | 0·34 (0·54) | –0·55 (–0·88) |

| West Virginia | 59·94 (96·46) | 91·46 (147·18) | 59·81 (96·25) | 91·44 (147·15) | –0·13 (–0·21) | –0·02 (0·04) |

|

| ||||||

| West | ||||||

| Alaska | 9·31 (14·99) | 156·24 (251·45) | 9·31 (14·98) | 154·26 (248·26) | 0·00 (0·00) | –1·99 (–3·20) |

| Arizona | 8·13 (13·08) | 20·94 (33·69) | 11·71 (18·84) | 31·80 (51·18) | 3·58 (5·76) | 10·87 (17·49) |

| California | 4·51 (7·26) | 10·85 (17·47) | 4·50 (7·24) | 10·95 (17·63) | –0·01 (–0·02) | 0·10 (0·16) |

| Colorado | 10·26 (16·51) | 25·73 (41·41) | 9·73 (15·66) | 20·08 (32·32) | –0·53 (–0·85) | –5·65 (–9·09) |

| Hawaii | 14·00 (22·54) | 29·97 (48·24) | 14·00 (22·54) | 30·20 (48·61) | 0·00 (0·00) | 0·23 (0·37) |

| Idaho | 26·79 (43·12) | 118·29 (190·37) | 24·65 (39·67) | 115·81 (186·37) | –2·14 (–3·45) | –2·48 (–4·00) |

| Montana | 27·82 (44·76) | 113·39 (182·48) | 74·02 (119·13) | 123·83 (199·29) | 46·21 (74·37) | 10·45 (16·81) |

| Nevada | 7·22 (11·62) | 13·26 (21·33) | 7·10 (11·43) | 12·06 (19·41) | –0·12 (–0·19) | –1·19 (–1·92) |

| New Mexico | 27·27 (43·89) | 102·09 (164·29) | 26·52 (42·67) | 112·45 (180·96) | –0·75 (–1·21) | 10·36 (16·67) |

| Oregon | 8·07 (12·99) | 36·05 (58·02) | 8·16 (13·12) | 35·77 (57·56) | 0·08 (0·13) | –0·29 (–0·46) |

| Utah | 29·51 (47·49) | 53·62 (86·29) | 29·35 (47·23) | 50·97 (82·03) | –0·16 (–0·26) | –2·65 (–4·26) |

| Washington | 6·11 (9·84) | 16·53 (26·61) | 6·36 (10·24) | 15·25 (24·55) | 0·25 (0·40) | –1·28 (–2·06) |

| Wyoming | 168·36 (270·95) | 273·04 (439·42) | 168·49 (271·16) | 275·01 (442·59) | 0·13 (0·21) | 1·97 (3·17) |

Data are miles (km).

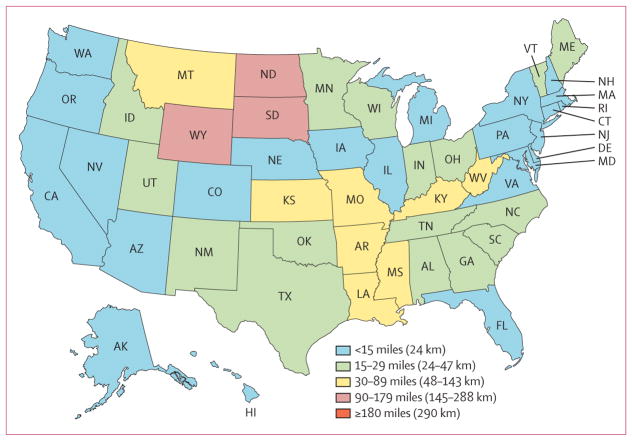

Figure 1. Median distance to the nearest abortion provider by state, 2014.

Alaska and Hawaii are inset in the bottom-left corner.

The median distance to the nearest clinic providing abortion services in 2014 was 15–29 miles (24–47 km) in 16 (32%) states and 30–89 miles (48–143 km) in eight (16%) states. At least half of all women in three (6%) states, including Wyoming (168·49 miles [271·16 km]), North Dakota (151·58 miles [243·94 km]), and South Dakota (92·06 miles [148·16 km]), would have had to travel more than 90 miles (145 km) to reach the nearest clinic.

The median state distances concealed sizable minorities of women who would have had to travel substantial distances to reach an abortion provider. For example, compared with the median distance of 9·31 miles (14·98 km) in Alaska, the 80th percentile distance showed that 20% of women in Alaska would have had to travel at least 154·26 miles (248·26 km) to reach the nearest abortion clinic in 2014 (table). In 26 (52%) states, at least 20% of women would have had to travel more than 50 miles (80 km) to reach the nearest facility providing abortion care.

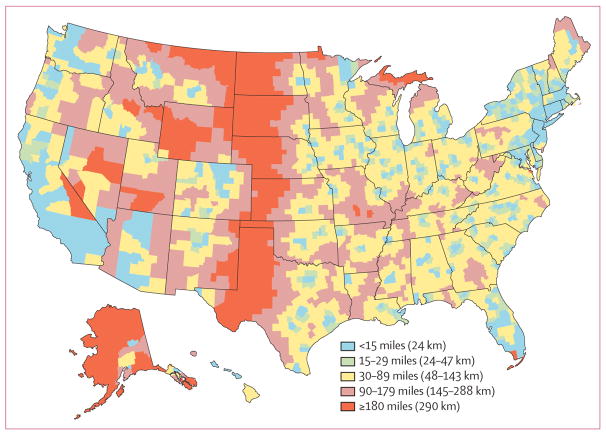

Examining distance to the nearest clinic by county provided a more complex picture (figure 2). Substantially more variation was seen between counties than between states, and women in many counties had to travel considerably further than their state median distance. However, even in states such as Texas, in which most of the landmass was far from an abortion clinic, most women lived reasonably close to an abortion clinic because of the concentration of both women and clinics in urban areas (appendix).

Figure 2. Median distance to the nearest abortion provider by county, 2014.

Alaska and Hawaii are inset in the bottom-left corner.

Counties where women would have had to travel 180 miles (290 km) or more to reach the nearest clinic were concentrated in the middle of the country, covering large portions of Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, and Texas. There were also areas with large travel distances in some states bordering Canada (Minnesota and Michigan), as well as pockets in California, Nevada, Utah, Idaho, and Missouri. Although geographically sizable, most of these areas were not densely populated and were generally rural (appendix). However, several of them were located in or near to medium or small metropolitan areas, the largest of which were located in Texas: Corpus Christi (324 000 residents), Lubbock (246 000), Amarillo (199 000), and Brownsville (183 000).

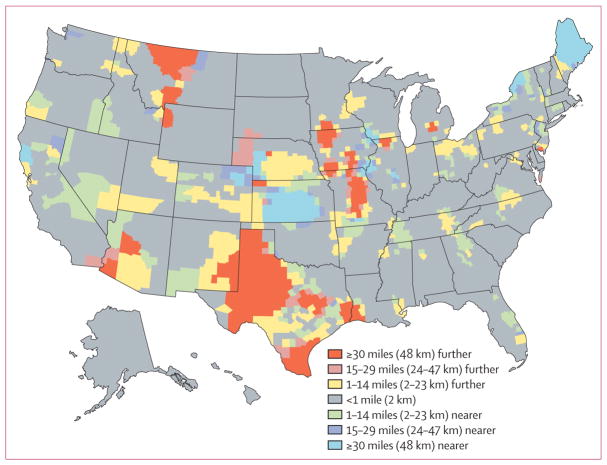

Between 2011 and 2014, the median distance a woman would have had to travel to reach an abortion clinic decreased in nine [18%] states; remained stable, changing no more than 1 mile (1·6 km) in 34 (68%) states; and increased in seven [14%] states (table). Most of the changes in distance to the nearest clinic were 5 miles (8 km) or less. The exceptions were Kansas (73·54 miles [118·35 km]) and Maine (20·81 miles [33·49 km]), where the median distance decreased, and Montana (46·21 miles [74·37 km]), North Dakota (14·46 miles [23·27 km]), and Missouri (7·45 miles [11·99 km]), where the median distance increased.

Similarly, little to no change was seen in the median distance to the nearest clinic in most counties (figure 3). Counties where the median distance to the nearest provider increased by 30 miles (48 km) or more were especially prominent in Texas, Iowa, Montana, and Missouri, and were present only outside large metropolitan areas (appendix). Texas and Missouri also had the largest increases in the 80th percentile distance that 20% of women would have had to travel to reach a clinic (56·50 miles [90·93 km] for Texas and 26·76 miles [43·07 km] for Missouri). Conversely, the 80th percentile distance increased by less than 1 mile in Iowa, and the median distance actually decreased by 5·45 miles (8·77 km) in this state (table). Although counties where the median distance to the nearest provider increased by 30 miles (48 km) or more were located in all four geographical regions, New Jersey was the only state in the northeast to show this degree of change. Counties where the median distance to a clinic increased by 15–29 miles (24–47 km) were more sparse than those where the median distance to the nearest provider increased by 30 miles (48 km) or more, although they too were not found in large metropolitan areas (appendix). These counties were also scattered across all four regions, although only one state in the northeast, Virginia, experienced this level of decline in access.

Figure 3. Change in median distance to the nearest abortion provider by county, 2011–14.

Alaska and Hawaii are inset in the bottom-left corner.

Counties where the median distance to the nearest clinic decreased by more than 30 miles (48 km) were most commonly in the midwest, occurring in Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, and Wisconsin. Distance to the nearest clinic also decreased by 30 miles (48 km) or more in counties in California and Colorado (in the west) and in Maine and upstate New York (in the northeast).

Our findings showed spatial disparities that were broadly unchanged in the period of 2011–14, despite several abortion restrictions being enacted during this period. We confirmed the consistency of the spatial disparities in our supplemental analysis of data from 2000. These spatial disparities have persisted for at least 15 years (appendix).

To assess the robustness of our results, we did a sensitivity analysis with inclusion of providers who did 200–399 abortions each year. State distances in 2014 were almost identical to those from the original primary analysis, with one exception: in Texas, the 80th percentile distance increased by 30 miles (48 km) because of a restrictive law that forced clinic closures (appendix).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to provide national estimates of spatial disparity in distance to the nearest abortion clinic for all women aged 15–44 years in the USA. Research has shown that living far from a provider can make abortion inaccessible.4–6 Travelling long distances can impose a substantial burden on women with respect to transportation costs, travel duration, time off work, and arrangement of childcare, particularly for women who are economically disadvantaged. However, distance can be contextualised within several factors that can affect access to abortion care. The presence of one nearby clinic does not necessarily show that the clinic meets the needs of all prospective patients, that it is open daily, or that it has the capacity to meet demand.28 Numerous barriers to access can have compounding effects on a woman’s ability to access care. For example, in 2014, 11 US states (an increase from nine states in 2011) required that a woman have in-person counselling, followed by waiting for 24–72 h, before obtaining an abortion (appendix). For these women, even seemingly short distances of 30 miles (48 km) can pose a substantial barrier to care because they would have to travel to and from the clinic twice (120 miles [193 km] in total).

Almost all patients who have an abortion in the USA are economically disadvantaged, and many either do not have health insurance or are unable to use insurance to pay for the procedure.8 These women might be able to travel to an abortion clinic, but they will be unable to access the service if they cannot afford to pay for the procedure. Distance might compound these cost barriers.

Most women would not have to travel considerable distances to reach an abortion clinic because almost all women and providers in the USA are in metropolitan areas. However, a sizable minority of women would have to travel 90 miles or more, and variation between counties is greater than between states. For example, in Alaska in 2014, half of all women lived 9·31 miles (14·98 km) or less from an abortion clinic, but a fifth of women lived 154·26 miles (248·26 km) or even further from a clinic; similar examples included Idaho, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, and Texas. Although half of all woman in the USA would have had to travel no more than 10·79 miles (17·36 km) to reach the nearest abortion clinic, 20% of women would have had to travel 42·54 miles (68·46 km) or more. Although policies are implemented at the state level, the consequences of restrictive legislation might not be felt equally across counties within a state; women in rural counties are likely to be most adversely affected by clinic closures.

Increases in distance in excess of 30 miles (48 km) between 2011 and 2014 were particularly evident in numerous counties in Texas, Missouri, Iowa, and Montana. All of these states, except for Iowa, adopted abortion restrictions during this period (appendix). These states were among those that had the largest proportionate decline in clinics.17 A hostile environment might have contributed to clinic closures, meaning that more women would have had to travel further to access care in 2014 than in 2011. By contrast, Iowa enacted no major restrictions during the study period and was not considered hostile to abortion rights, although it had five fewer clinics in 2014 than in 2011 (appendix). Research has suggested that efforts to increase access to long-acting contraceptive methods in Iowa might have contributed to reductions in the number of abortions.29 Reduced need for abortion services might have contributed to the decline in clinics and, in turn, the increase in distance that some women in some counties would have to travel for an abortion. The median distance to a clinic decreased by about 5 miles (8 km) for Iowa during the study period, suggesting that abortion services were redistributed and that women, particularly those living in metropolitan areas, would not have had to travel quite as far.

Texas was an outlier in that the distance that 20% of women would have had to travel increased by about 56 miles (90 km). This finding was probably due to an abortion restriction enacted in 2013 requiring that physicians who provide abortion care have admitting privileges at nearby hospitals. This law resulted in the closure of more than half of the abortion care facilities in the state between 2013 and 2014.30 Our estimates of distance to nearest provider for women in Texas in 2014 are probably too low because they were calculated with inclusion of facilities that provided at least 400 abortions in 2014, several of which were closed at some point that year.31 Although some of the more onerous restrictions were struck down by the Supreme Court in June, 2016, most clinics have not yet reopened,4 and the distance to the nearest provider has probably not improved.

The median distance to the nearest provider decreased by more than 20 miles (32 km) in Kansas and Maine. A new clinic opened in Kansas, and two clinics in Maine had increased caseloads so that they provided 400 or more abortions in 2014. These findings suggested that abortion might have become more accessible for women in these states.

This study had several limitations. First, there are numerous barriers to abortion access in the USA, and distance is not the only obstacle. Abortion restrictions, stigma, and financial constraints could prevent a woman from having an abortion, regardless of distance. Second, our estimates might be conservative because they do not capture the effect of mandated counselling and waiting periods, which might force women to make multiple trips to an abortion clinic. Third, a woman might not visit the closest abortion provider to her home; for example, the closest provider might not offer the necessary or desired services. Fourth, our analysis did not capture women’s qualitative experiences. Fifth, the inclusion criteria might have affected the measured distances, but modifying these criteria would have led to inclusion of locations that were not public points of access. Finally, although we documented spatial disparities, it was beyond the scope of our analysis to fully address their causal determinants (eg, reduced demand for services might have affected a clinic’s ability to support itself).

In conclusion, abortion is an important component of reproductive health, and restricting access to abortions can lead to them being done later or under potentially unsafe conditions. Our analysis showed substantial and persistent spatial disparities in access to abortion. Enacting restrictions at the state level is a stated priority of many policy makers.32 Such efforts, if successful, could not only reduce access to abortion, especially for economically disadvantaged women who might not have the resources to overcome obstacles posed by travel, but could potentially exacerbate existing spatial inequality.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Between Feb 1, 2017, and April 1, 2017, we searched Google Scholar for studies about spatial inequality in abortion access using the search terms “abortion and distance”, “abortion access”, and “spatial inequality”. We reviewed the reference lists and reverse citations of relevant articles. Studies of high-income countries in which abortion is legal have identified spatial disparities in access to abortion facilities. Within the USA, studies using data from individual states have shown an inverse association between distance to nearest abortion provider and county abortion incidence. Meanwhile, many areas of the USA are implementing restrictive policies aimed at curtailing abortion. However, no national study has examined spatial inequality in access to abortion in the USA.

Added value of this study

We present the first national estimates of spatial disparities in distance to the nearest abortion provider in the USA. This study is also the first to take into account the geographical distribution of women. This approach allowed estimation of the median distance that a woman would have to travel to an abortion provider in each county and state and the 80th percentile distance that 20% of women in each state live from the nearest clinic. We characterised spatial disparities within and across states, and the stability of these disparities over a 15 year period, from 2000 to 2014.

Implications of all the available evidence

We showed persistant spatial disparities in women’s access to abortion in the USA that might be applicable to women in other high-income countries.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by an anonymous grant to the Guttmacher Institute. We thank Lawrence Finer, Kathryn Kost, Rachel Gold, Elizabeth Nash, Megan Donovan, and Adam Sonfield for reviewing drafts of this report and Liza Fuentes for her insight during peer review.

Footnotes

Contributors

JMB led the conceptualisation of the research and analysis of data. RKJ led the Abortion Provider Censuses and contributed to conceptualisation of the research. KLB contributed to data collection, geocoded the data, and co-led the analysis, under the supervision of JMB and RKJ. All authors contributed to interpretation of the results and writing of this report.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. ACOG Committee opinion no 613: increasing access to abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:1060–65. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000456326.88857.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Public Health Association. Restricted access to abortion violates human rights, precludes reproductive justice, and demands public health intervention. [accessed Dec 13, 2016];Policy number 20152. 2015 https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2016/01/04/11/24/restricted-access-to-abortion-violates-human-rights.

- 3.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:843–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1506575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grossman D, White K, Hopkins K, Potter JE. Change in distance to nearest facility and abortion in Texas, 2012 to 2014. JAMA. 2017;317:437–39. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.17026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shelton JD, Brann EA, Schulz KF. Abortion utilization: does travel distance matter? Fam Plann Perspect. 1976;8:260–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joyce TJ, Tan R, Zhang Y. Back to the future? Abortion before & after Roe. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham S, Lindo JM, Myers C, Schlosser A. How far is too far? New evidence on abortion clinic closures, access, and abortions. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jerman J, Jones RK, Onda T. Characteristics of US abortion patients in 2014 and changes since 2008. New York, NY: Guttmacher Institute; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doran F, Nancarrow S. Barriers and facilitators of access to first-trimester abortion services for women in the developed world: a systematic review. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2015;41:170–80. doi: 10.1136/jfprhc-2013-100862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sethna C, Doull M. Spatial disparities and travel to freestanding abortion clinics in Canada. Womens Stud Int Forum. 2013;38:52–62. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silva M, McNeill R. Geographical access to termination of pregnancy services in New Zealand. Aust NZ J Public Health. 2008;32:519–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2008.00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nickson C, Smith AMA, Shelley JM. Travel undertaken by women accessing private Victorian pregnancy termination services. Aust NZ J Public Health. 2006;30:329–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2006.tb00844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nickson C, Shelley J, Smith A. Use of interstate services for the termination of pregnancy in Australia. Aust NZ J Public Health. 2002;26:421–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2002.tb00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nash E, Gold RB, Ansari-Thomas Z, Cappello O, Mohammed L. Policy trends in the states: 2016. New York, NY: Guttmacher Institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones RK, Jerman J. How far did US women travel for abortion services in 2008? J Womens Health. 2013;22:706–13. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerdts C, Fuentes L, Grossman D, et al. Impact of clinic closures on women obtaining abortion services after implementation of a restrictive law in Texas. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:857–64. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones RK, Jerman J. Abortion incidence and service availability in the United States, 2014. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2017;49:17–27. doi: 10.1363/psrh.12015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jatlaoui TC, Ewing A, Mandel MG, et al. Abortion surveillance— United States, 2013. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016;65:1–44. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6512a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.US Census Bureau. [accessed June 15, 2017];Geographic terms and concepts—block groups. 2010 https://www.census.gov/geo/reference/gtc/gtc_bg.html.

- 20.US Census Bureau. [accessed June 14, 2016];Centers of population. http://www.census.gov/geo/reference/centersofpop.html.

- 21.Huber S, Rust C. Calculate travel time and distance with OpenStreetMap data using the Open Source Routing Machine (OSRM) Stata J. 2016;16:416–23. [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Census Bureau/American FactFinder. 2000 Census. US Census Bureau; 2000. P12: sex by age. [Google Scholar]

- 23.US Census Bureau/American FactFinder. 2010 Census. US Census Bureau; 2010. P12: sex by age. [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Census Bureau. [accessed June 26, 2017];County population totals tables: 2010–2016. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2016/demo/popest/counties-total.html.

- 25.Ingram DD, Franco SJ. 2013 NCHS urban-rural classification scheme for counties. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones RK, Jerman J. Abortion incidence and service availability in the United States, 2011. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2014;46:3–14. doi: 10.1363/46e0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iowa Community Indicators Program. [accessed Feb 21, 2017];Urban percentage of the population for states, historical. http://www.icip.iastate.edu/tables/population/urban-pct-states.

- 28.Texas Policy Evaluation Project. [accessed July 25, 2016];Abortion wait times in Texas: the shrinking capacity of facilities and the potential impact of closing non-ASC clinics. 2015 http://sites.utexas.edu/txpep/files/2016/01/Abortion_Wait_Time_Brief.pdf.

- 29.Biggs MA, Rocca CH, Brindis CD, Hirsch H, Grossman D. Did increasing use of highly effective contraception contribute to declining abortions in Iowa? Contraception. 2015;91:167–73. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grossman D, Baum S, Fuentes L, et al. Change in abortion services after implementation of a restrictive law in Texas. Contraception. 2014;90:496–501. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fuentes L, Lebenkoff S, White K, et al. Women’s experiences seeking abortion care shortly after the closure of clinics due to a restrictive law in Texas. Contraception. 2016;93:292–97. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gold RB, Starrs AM. US reproductive health and rights: beyond the global gag rule. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2:e122–23. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30035-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]