Abstract

The process of initiating lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) cultural competencies and educational interventions developed to increase staff knowledge on LGBT culture and health issues is discussed, including a computer-based module and panel discussion. The module intervention showed a statistically significant increase (p = .033) of staff LGBT knowledge from pretest to posttest scores. An evaluation after the panel discussion showed that 72% of staff indicated they were more prepared for LGBT patient care.

Nurse professional development (NPD) practitioners can assess for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) cultural competencies in healthcare settings and initiate interventions to increase competencies as indicated. A 2012 Gallup survey conducted in the United States of 120,000 adults found that 3.4% self-identified as LGBT (Gates & Newport, 2012). This equates to approximately 9 million LGBT adults (Gates, 2011). There are approximately 1.4 million transgender adults in the United States (Flores, Herman, Gates, & Brown, 2016). One major problem with identifying numbers of people in the LGBT population is that there is limited data collection in national surveys and within individual healthcare settings, which creates invisibility of this patient population (Makadon, 2011).

Background

In 2011, The Joint Commission published LGBT cultural competencies for healthcare settings. These competencies were created in response to a 2011 report released by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), which examined health of the LGBT population (IOM, 2011). In response to the IOM report findings of LGBT health disparities, Healthy People 2020 created a goal to improve the well-being, safety, and health of the LGBT patient population (HealthyPeople.gov, 2016).

Local Problem

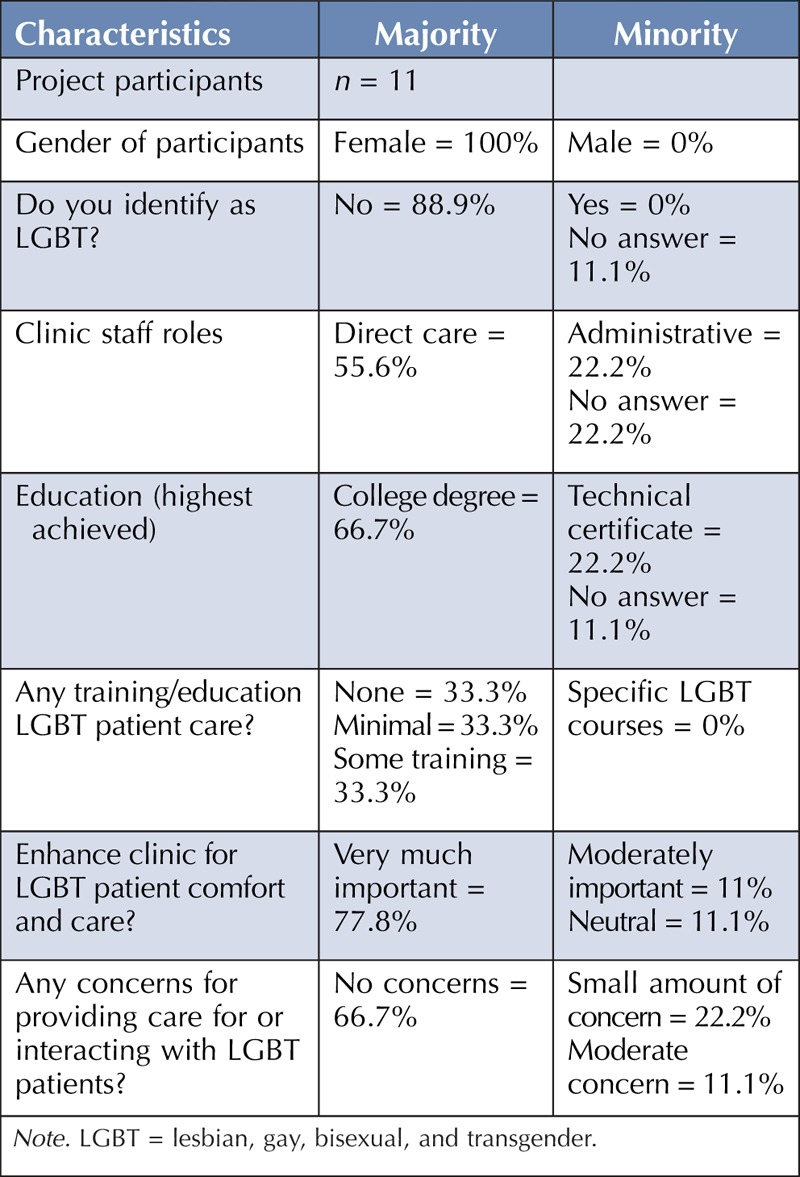

Data from the 2010 Census reported over 10,000 same-sex couples residing in the state of Minnesota (Gates & Cooke, n.d.; Gates, 2015). The Rainbow Health Initiative (RHI) Directory for the state of Minnesota listed only 28 LGBT-friendly general providers in January 2017 (RHI, n.d.). A preliminary assessment of the primary care clinic setting used for this quality improvement (QI) initiative found that limited LGBT cultural competencies were present. There were no visual signs to identify the clinic as friendly or welcoming for LGBT patients. The content of the clinic’s admission intake form did not include questions or language pertinent to providing an opportunity for patients to self-identify as LGBT; however, one clinician chart form had a question about sexual orientation (SO). No questions were present on any clinic form that inquired about the patient’s gender identity. An informal staff survey was conducted through in-person interviews. Staff members explained that care for LGBT patients had not been addressed during staff orientation or subsequent trainings. A baseline assessment of the clinic staff education revealed a lack of LGBT-specific training on patient care (see Table 1). A learning needs assessment was completed by nine clinic staff members. Results of the assessment included the following: nine (100%) wanted to learn LGBT-related terms, eight (88.9%) desired information on LGBT health-related risk factors, eight (88.9%) wanted recommendations on LGBT health screening, and eight (88.9%) desired information on websites for online LGBT educational modules.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Assessment Findings

Literature Review

Poor health outcomes occur for LGBT patients in part due to a lack of LGBT cultural competency in healthcare settings (Krehely, 2009). Guidelines for providing care to LGBT patients recommend displaying a visible LGBT symbol for patients and having LGBT visual cues present in the healthcare facility (Gay & Lesbian Medical Association [GLMA], n.d.; The Joint Commission, 2011). In October 2015, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology issued Final Rules that require electronic health records (EHRs) certified in Meaningful Use to include SO/gender identity fields (Cahill, Baker, Deutsch, Keatley, & Makadon, 2016, p. 100). Cahill et al. (2014) found that asking questions about SO/gender identity is feasible to implement and important information to provide appropriate care for LGBT patients.

Providing safe clinical environments for LGBT patients was found to be an important aspect in the literature, especially for transgender youths (Torres et al., 2015; Unger, 2015). Torres et al. (2015) found that a nurturing healthcare environment and social support from family, school, and community settings help to improve resiliency for transgender youth. The literature showed support in patient understanding and feasibility of asking questions about their SO and gender identity (Cahill et al., 2014). Most patients felt that the two-step gender identity questions (asking about their sex assigned at birth and their current gender identity) were understood for the reasons asked and felt that they were important questions for receiving proper care (Cahill et al., 2014). A knowledge gap of LGBT cultural and clinical competencies of healthcare providers and staff was a common literature finding (Unger, 2015; Moll et al., 2014; Torres et al., 2015; Klotzbaugh & Spencer, 2015). Limited formal education on LGBT patient care was provided to physicians/residents (Unger, 2015; Moll et al., 2014, Torres et al., 2015).

The GLMA guidelines on LGBT patient care include staff education on LGBT health issues, risk factors, and the use of appropriate language related to the LGBT culture (GLMA, n.d., p. 14). Professional education on LGBT health care is lacking in both formal educational and informal staff training sessions (Crisp, 2006; Kirkpatrick, Esterhuizen, Jesse, & Brown, 2015). A knowledge gap exists for providers, because less than 50% of physician education programs address LGBT health and only 16% have comprehensive training (Arbeit, Fisher, Macapagal, & Mustanski, 2016). Lim, Brown, and Kim (2014) described negative attitudes of nursing students toward care for LGBT patients and a knowledge gap in LGBT health concerns in correlation with limited experience caring for the LGBT patient population and nursing curricula that has limited content on LGBT health issues.

Training and education should be delivered by using multiple modalities due to the variety of learning style differences in adult learners (The Joint Commission, 2011). This includes providing an opportunity for staff to meet for open and honest discussions regarding questions or concerns they have about LGBT patient care (The Joint Commission, 2011). Bluestone et al. (2013) found that computer-based learning can be developed to be more cost-efficient and more effective than live instruction with use of effective techniques (Bluestone et al., 2013). This allows for learning that is self-directed, convenient, and at a comfortable pace for each learner (Bluestone et al., 2013). In addition, evidence suggests a positive influence on attitudes toward LGBT populations with use of a panel discussion (Green, Dixon, & Gold-Neil, 1993; Parkhill, Matthews, Fearing, & Gainsburg, 2014). This teaching strategy was found to be more effective than a lecture method (Angeline, Renuka, & Shaji, 2015). High-quality culturally competent staff training can be provided during orientation, diversity training, and mandatory education (The Joint Commission, 2011). To reinforce learning, it is recommended to use repetitive training that is targeted to the audience (Bluestone et al., 2013). Content for this QI project staff education program focused on enhancing equity care (a welcoming environment for LGBT patients), patient-centered care (providing an opportunity for patients to self-identify as LGBT), and quality care (addressing pertinent LGBT health issues with patients as needed) in the healthcare setting.

Rationale

The rationale for implementing LGBT cultural competencies in the chosen primary care clinic setting was based on the clinic baseline assessments indicating a staff knowledge gap in culture and health issues for LGBT patients. The Joint Commission LGBT cultural competence checklist identified gaps when assessing the clinic’s environment, intake questions, and staff knowledge. The problem of limited LGBT cultural competencies was identified in the clinic through preliminary and baseline assessments. The clinic staffs’ motivation and change capacity was determined through in-person discussions with each staff member. Lippitt’s change theory guided this QI initiative. The seven phases of change were used to assist with each step from beginning to end of the QI project (Kelly, 2008). The seven phases of Lippitt’s change theory include the following: (1) diagnose the problem, (2) assess the capacity for change and motivation, (3) assess the change agent motivation and resources, (4) select objectives for creating the change, (5) choose a role for the change agent, (6) maintain the change, and (7) terminate the helping relationship (Kelly, 2012, p. 300).

Addressing the first phase of Lippitt’s change theory, the problem of limited LGBT cultural competencies was identified in the clinic through preliminary and baseline assessments. For the second phase, change capacity and motivation of clinic staff were determined through in-person discussions with each staff member. A personal family situation and a desire to gain knowledge about LGBT provision of care by the project leader met the third phase of the change theory. The fourth phase included the development of objectives that were approved by the project advisor and clinic director for implementation of three evidence-based LGBT cultural competencies within the time frame of February 2017 to May 2017. For the fifth phase, the project leader embraced the role of a LGBT consultant for the clinic. The sixth phase of Lippitt’s change theory was addressed by working with the clinic director on development of a plan for maintenance and sustainability through ongoing meetings with the clinic director and discussion of finding a clinic champion. For the seventh (last) phase of Lippitt’s change theory, the project leader, clinic director, and two key clinic stakeholders mutually agreed upon a time for termination of the helping relationship, and a telephone meeting occurred with these stakeholders for a final sustainability discussion and project relationship termination.

Project Aim

The identified aim of this QI project was to enhance patient care in a primary care clinic by incorporating three LGBT cultural competencies as measured with use of a checklist developed by The Joint Commission. The purpose of this project was to enhance equitable care, quality care, and patient-centered care for LGBT patients in a clinic setting. Outcome objectives of this initiative included incorporating three LGBT cultural competencies into a primary care clinic setting by May 2017 and increasing staff knowledge on LGBT patient care by 60% on pretest to posttest scores.

METHODS

There were 11 clinic staff participants for the QI project, which included 10 employees and one clinic director. The setting for this initiative was a primary care clinic located in an urban area in the Midwest region of the United States. A baseline assessment provided the project leader with information on participants that included general demographics, feedback on enhancing clinic LGBT cultural competencies, and learning needs on LGBT culture and health issues (see Table 1). The stakeholders included the project leader, project advisor, clinic director, and clinic employees. The project team included the project leader, project advisor, statistician, clinic director, and clinic manager. The project leader consulted with an outside LGBT community specialist for guidance.

Planning Process

The project leader began the planning process for the educational programs by meeting individually with each staff member to ask about their previous experience in caring for patients who identify as LGBT. The project leader also asked about the professional education they received on providing care to patients who identify as LGBT. During this preliminary assessment, it was found that most staff members had a desire to learn about the LGBT culture and health issues. Staff members disclosed that they had received either no or minimal education on LGBT culture or health issues. The preliminary findings were shared with key stakeholders who determined that this project was important to implement in this healthcare setting. The project leader then created questions for a formal three-page baseline assessment. All three components of the baseline assessment were found to have face validity.

There were three questions on the learning needs assessment form. The first question asked participants which topics on LGBT culture or health needs would be helpful. Four choices were provided with one write-in choice of “other.” The four choices included LGBT-related terms, families and relationships, health-related risk factors, and healthcare screening recommendations. All nine (100%) of the participants who completed the learning needs questionnaire identified the desire to learn about LGBT-related terms, six (66.7%) indicated they wanted information on LGBT families and relationships, eight (88.9%) indicated they wanted information on healthcare screening recommendations, and one (11.1%) participant chose to write in a request with the “other” choice. This written request stated, “Biggest ‘Do Nots’ when taking care of LGBT.” The second question on the learning needs assessment form asked if they have any specific questions about LGBT patient care that they would like addressed in the educational module with a space to write in their request. There were four (44.4%) who answered “yes” to this question. Written responses included “language to use around questions if they have had surgery during their transition”; “correct gender terms to use”; “guidance/support during transgender therapies”; and “how to address, ask questions about past med hx, current partners, appropriate term usage.” The third question asked what type of resources would be helpful to their clinic role for providing care to LGBT patients. Two choices were provided, which included a list of LGBT-friendly providers in their city or state and websites for additional online educational modules. A third choice was “other” with a space provided for writing in a type of resource they would find helpful. Results included the following: seven (77.8%) indicated that they would like a list of LGBT-friendly providers in their city/state, eight (88.9%) indicated that they would like websites for additional online educational modules, and one (11.1%) chose “other” and wrote “Preventative health measures.”

Interventions

The project leader implemented three LGBT cultural competencies present in a checklist developed by The Joint Commission. Competencies from the checklist used for this project included the following: (a) “create a welcoming environment that is inclusive of LGBT patients,” (b) “facilitate disclosure of sexual orientation and gender identity,” and (c) “incorporate LGBT patient care information in new or existing employee staff training” (The Joint Commission, 2011, pp. 35–37).

Clinic Environment Interventions

Creating a healthcare environment that is welcoming and friendly toward LGBT individuals is a recommendation included in nationally published guidelines by The Joint Commission (2011), the Human Rights Campaign Foundation (2016), and the GLMA (n.d.). These guidelines recommend adding LGBT signage and nondiscrimination policies as interventions. An LGBT symbol and nondiscrimination statement were placed at the front desk in the clinic’s patient waiting area to create a welcoming and friendly clinic environment (Competency 1). An 8-inch by 10-inch poster of a rainbow heart symbol with the statement “All Are Welcome Here” was framed and placed at the clinic’s front desk. The project leader and clinic director mutually chose and agreed upon this symbol.

Intake Questions Interventions

Specific intake questions that assist LGBT patients with self-identification have been published by various healthcare agencies: Health Resources and Services Administration (2016), The Joint Commission (2011), GLMA (n.d.), Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (Tagalicod, 2013), and the Center of Excellence for Transgender Health at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) (Deutsch, 2017a). Published guidelines include asking questions that address SO and gender identity (Ard & Makadon, n.d.). Evidence-based questions from the Fenway Institute and the RHI pertinent to allowing LGBT patients to self-identify were provided to the clinic director to incorporate into the admission intake (Competency 2). The project leader created a patient intake form of seven questions and provided it to the clinic director to use for all clinic patients to complete at visits.

Staff Knowledge Interventions

The training of all healthcare facility staff on competent care of LGBT patients is recommended by multiple agencies: The Joint Commission (2011), Human Rights Campaign Foundation (2016), GLMA (n.d.), and UCSF (Deutsch, 2017b). For this QI project, two educational programs were provided as interventions to increase staff knowledge of LGBT culture and health issues (Competency 3). The first session was a one-time 1-hour computer-based educational module that was completed by staff members individually. Content of the educational module was based on identified learning needs found during the baseline assessment conducted by the project leader. The second session was a one-time in-person, 90-minute panel discussion that included four experts in LGBT services. The panel consisted of professionals who provide LGBT-focused care for homeless youth, victim advocacy, transgender health care, and mental health/substance abuse counseling. The topics and content were developed based on verbal feedback that the project leader received from staff about the lack of knowledge they had of local LGBT resources. The panel discussion was videotaped for future use during orientation and annual staff trainings. Permission was obtained prior to videotaping.

Measures

The project leader created a checklist using three Joint Commission LGBT cultural competencies, which were marked as present, limited, or absent. The project leader identified a list of competencies in Appendix A of The Joint Commission Field Guide (2011), and three competencies were chosen and used as a measure to determine their presence or absence (The Joint Commission, 2011). A baseline assessment tool was developed by the project leader, which consisted of demographic questions, LGBT patient care-related questions, and learning needs questions for clinic staff. The project advisor and statistician determined that the assessment forms had face validity. Participants were deidentified on all forms.

In this QI initiative, the project leader chose a pretest and posttest design for evaluation of the computer-based module to measure staff knowledge. All participants were deidentified. The pretest and posttest consisted of the same 12-item questionnaire to determine if a change in LGBT patient care knowledge occurred among participants. The pretest and posttest had face validity as determined by the project advisor and statistician. Participants completed the pretest prior to starting the computer-based module. The posttest was administered immediately after module completion.

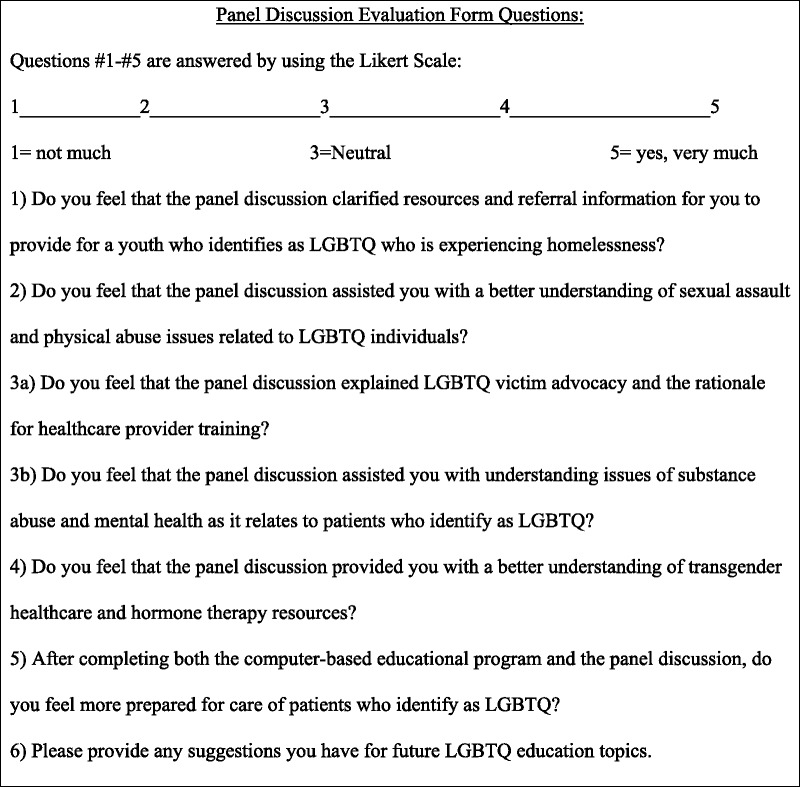

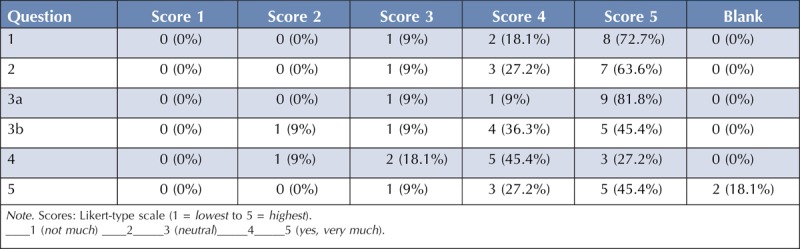

At the conclusion of the panel discussion, participants were asked to complete a five-question evaluation form, evaluating the discussion of the topics of resources and referral information for LGBT youth homelessness, sexual assault and physical abuse issues, victim advocacy, substance abuse and mental health issues, transgender health care, and if participants felt more prepared for LGBT patient care (see Figure 2). The project leader used a Likert-type scale for the evaluation form, which ranged in scoring from 1 (lowest) to 5 (highest), and included one open-ended question to collect qualitative feedback from participants.

FIGURE 2.

Panel discussion evaluation form. Note. LGBTQ = lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning.

Data Analysis

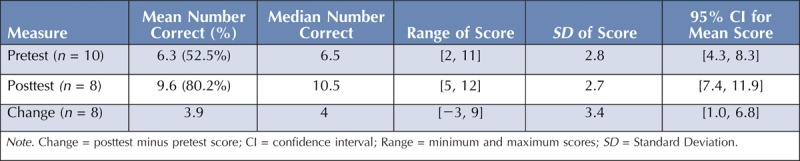

Data analysis of the pretest and posttest scoring determined the mean number (%) correct, standard deviation of score, median number correct, range (min, max) of score, and 95% confidence interval for the mean scores. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test (nonparametric version of the paired t test) was performed on the change scores to determine if there was a statistically significant relationship between the intervention and participant score results.

Ethical Considerations

An online institutional review board (IRB) determination tool for the University of Minnesota IRB was used for a review of human subjects’ protection for this QI initiative of enhancing clinic LGBT cultural competencies. This QI project did not meet the federal definition of Human Subjects Research, and therefore, no additional IRB review was required. The clinic did not require a separate IRB submission. Participants in this project were kept anonymous by using a code for deidentification. No outside funding was received for this project. The project leader had no conflicts of interest with this QI initiative.

RESULTS

The project leader used the Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) cycle for initiation and evolution of the interventions. Initiation of the computer-based module included assessing the learning needs of the staff (Plan), developing a computer-based educational module to include identified knowledge gaps (Do), studying the pretest/posttest and panel discussion evaluation form statistical data (Study), and then revising the staff educational interventions to better meet participants’ needs (Act). Modifications based on the PDSA cycle made by the project leader included changing the computer-based module by creating a series of separate training modules instead of one comprehensive module. It was determined that the module would better meet the individualized learning needs of staff with this change by allowing each participant to have the ability to choose which module sections were pertinent to their clinic role.

Findings

Upon completion of the QI project, the clinic’s LGBT cultural competencies were evaluated using The Joint Commission 2011 Field Guide checklist. Results revealed that the clinic gained three cultural competencies after completion of the project interventions. The first competency of creating a more inclusive clinic environment was obtained by the prominent display of a symbol that embraced diversity. This provides LGBT patients with a visual cue that they are welcome in the clinic. The second competency of facilitating disclosure of LGBT self-identity was achieved by the addition of SO/gender identity questions. The questions are posed to patients verbally with plans to be incorporated into the clinic EHR. Competency 3 was a gain in LGBT staff knowledge as measured with pretest/posttest score analysis (see Table 2). In addition, clinic staff acknowledged feeling more comfortable with care for LGBT patients as indicated on the responses to Question 5 of the panel discussion evaluation form. These findings revealed that 72% participants scored higher (4 or 5) than neutral (3) on the evaluation form scale for Question 5, indicating they felt more prepared to care for LGBT patients.

TABLE 2.

Pretest and Posttest Data Analysis

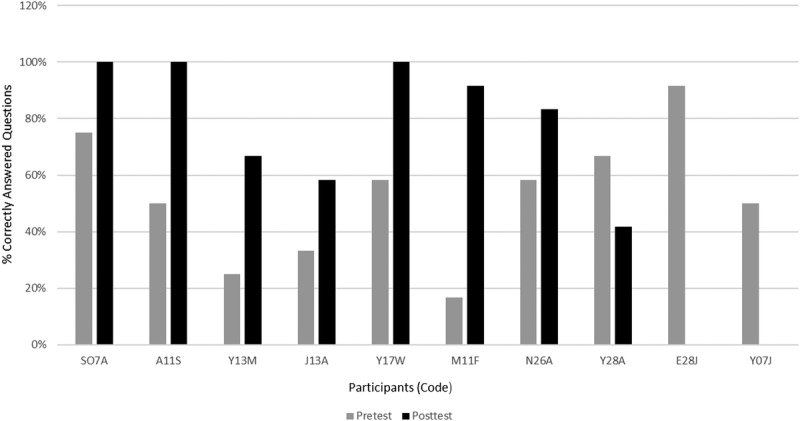

The project leader compared participant pretest and posttest scores (see Figure 1). Ten participants completed the pretest, and eight participants completed the posttest. Data analysis of pretest and posttest scores can be seen in Table 2. The median change score was 4, exhibiting a shift to the right from pretest to posttest scores. This shift signifies that the knowledge gain was related to the educational intervention and not by chance. A statistically significant increase (p = .033) of pretest to posttest change scores was found using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for participants who completed the computer-based educational module. Missing data included two posttests that were not submitted to the clinic manager. The results of one participant were an outlier with a higher pretest score than posttest score. The project leader did not know why this occurred. Prior to the panel discussion, two staff member participants explained to the project leader that they did not want to consent to being videotaped during the panel discussion. These two staff members chose to sit in the back of the room during the panel discussion and did not participate in staff discussions with panelists.

FIGURE 1.

Participant pretest and posttest scores.

Panel discussion questions are provided in Figure 2. Results of panel discussion participant evaluation form scores are in Table 3. No participants scored any of the evaluation questions with the lowest score (1 out of a total of 5) on the Likert scale. For Questions 1, 2, and 3a, most participants (72.7%, 63.6%, and 81.8% respectively) scored these questions the highest score on the Likert scale (5 out of a total of 5). Question 6 on the evaluation form asked participants to provide suggestions for future LGBT education topics in which 10 (90.9%) left this blank and 1 (9%) provided a written answer. The written answer for Question 6 stated, “The panel discussion was amazing & very educational. The computer-based program was much too long, pace could have been faster. The content should be directed toward the appropriate staff.”

TABLE 3.

Panel Discussion Evaluation Form Scores

Costs that were associated with this QI project included loss of clinic income during the 90-minute time frame that the clinic was closed for the panel discussion. In addition, staff were paid for their time to complete the 1-hour computer-based educational module and to attend the 90-minute panel discussion. Nominal costs were incurred by the project leader for purchase of a frame for the LGBT symbol and nondiscrimination statement placed at the front desk.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was met because all three cultural competencies implemented in this project were integrated into clinic patient care and measured using tools determined to have face validity. A key finding of this QI project included a significant increase (p = .033) in staff participant pretest to posttest scores, which measured knowledge of LGBT culture and health issues learned from completion of the computer-based educational module. In addition, 72% of staff identified they felt more prepared to care for LGBT patients after completing the computer-based educational module and panel discussion.

Lessons Learned

Many lessons were learned by overcoming various barriers and obstacles while implementing this QI project. Barriers exist for LGBT healthcare access and staff training (Moll et al, 2014; Torres et al., 2015). Moll et al. (2014) identified barriers to providing emergency department residents with training on LGBT health, which included perceptions that there was no need for training, no time available, no interest by faculty, and no support for training. When the project leader asked about LGBT cultural competencies in the clinic setting prior to performing assessments, the initial verbal responses from the clinic director and staff members included that they treat everyone equal and did not feel they had a need for addressing LGBT cultural competencies. Challenges included addressing employee bias, identification of the healthcare setting’s LGBT patient population, and QI team communication for implementing LGBT cultural competencies. To address the challenge of employee bias, discussing cultural humility with the staff was a good starting point. This included an individualized process of self-reflection on thoughts and biases with regard to provision of care for patients who identify as LGBT. To address the challenge of identifying the clinic’s LGBT patient population, data presently collected within the EHR to identify LGBT patients were determined. If there are no intake questions that identify LGBT patients in the EHR, it presents a dilemma for baseline data (preintervention health outcome measures or patient satisfaction survey results) to be used for comparing with postimplementation findings. This is one reason that this population of patients has difficulty with invisibility within the healthcare system.

Challenges of performing this QI project included difficulties that occurred with communication between the project leader and the clinic director, which initially impeded progress on the project. To address this challenge, the project leader and clinic director met and discussed the causes of the communication breakdown. Resolution occurred through scheduling regular telephone weekly meetings, which improved communication and project progression. Another challenge was the inability to easily incorporate the SO/gender identity questions into the EHR due to organizational constraints on altering the electronic intake form. A paper intake form with SO/gender identity questions was created to temporarily compensate.

Limitations

A limitation of this QI project included a small sample size (n = 11). The clinical site for this QI project was small with a limited number of staff employees. In addition, the patient population was low, possibly due to the clinic being new to the community. Therefore, the results from this QI project are not generalizable to other healthcare settings.

NPD Practitioner Role

The NPD practitioner role for integrating LGBT cultural competencies into a healthcare setting encompassed planning, implementation, and evaluation of the staff educational programs to increase LGBT patient care knowledge. Planning entailed being a member of a QI team that began with reviewing The Joint Commission checklist for LGBT cultural competencies to determine knowledge gaps. Use of a baseline assessment helped collect preintervention data and identify aspects of LGBT patient care that needed to be addressed. The NPD practitioner determined learning objectives for the computer-based module and used measures to determine changes in staff knowledge. Using a baseline assessment and the GLMA guidelines for evidence-based care of LGBT patients, the NPD practitioner developed the training content needed for enhancing staff knowledge. Measures included a knowledge pretest and posttest and tools to determine if the panel discussion learning objectives were met and if there was a change in staff feeling more prepared to care for LGBT patients.

Conclusion

This QI project provided the clinic with an enhancement of three LGBT cultural competencies, which address equity, quality, and patient-centered care. Interventions focused on creating a welcoming environment to help increase equity of care, asking SO/gender identity intake questions to assist with patient-centered care, and increasing staff knowledge to possibly help with provision of higher-quality LGBT patient care. Because of a small sample size, this project is not generalizable to other healthcare settings. Future projects can focus on LGBT patient health outcomes and satisfaction of care following cultural competency implementation.

NPD practitioners can assist their healthcare facility to meet LGBT cultural competencies by integrating routine staff training on LGBT culture, health issues, and patient care. Content should be evidence-based and can be determined with use of staff assessments combined with integration of existing guidelines (such as GLMA guidelines) that address LGBT patient care. Planning should begin with identifying stakeholders and developing a collaborative QI team approach for a system-wide change. The NPD practitioner can take a leadership role in the development of educational interventions, and implementation should be coordinated with the management team. Communication for team collaboration for implementation of LGBT cultural competencies in a healthcare setting can be difficult if some team members have concerns about implementation. Developing a regular schedule of meetings with the QI team and addressing individual team member cultural humility may be helpful to initiate at the beginning of the QI team process. Educational program content should be updated on a regular basis to keep information congruent with recommended evidence-based guidelines. Participant feedback and data findings will assist the NPD practitioner with changes to future PDSA cycles. Measures should be used to determine outcomes of the QI implementation interventions. The NPD practitioner can oversee that staff complete a pretest before starting the computer-based module and follow up with a posttest after module completion. Other aspects to consider included providing staff with access to a computer to use for the educational intervention, a private location for participants to complete the module, and provision of time for module completion. For the panel discussion, the NPD practitioner can consider attaining a location to hold the panel discussion and work in collaboration with management to determine staff attendance and speaker compensation.

Findings of staff knowledge changes, patient satisfaction survey results, and LGBT patient health outcomes should be shared with administration, management, and staff to continue with motivation for sustainability of this initiative. NPD practitioners can provide staff training on a regular basis through orientation and annual staff education requirements. For sustainability, the NPD practitioner can identify LGBT cultural competency champions within the staff and provide any updated changes with LGBT patient care guidelines, reinforce information learned, and assist with policy development.

Footnotes

The author has disclosed that she has no significant relationship with, or financial interest in, any commercial companies pertaining to this article.

References

- Angeline K., Renuka K., & Shaji J. C. H. (2015). Effectiveness of lecture method vs. panel discussion among nursing students in India. International Journal of Educational Science and Research. 5(1), 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Arbeit M. R., Fisher C. B., Macapagal K., & Mustanski B. (2016). Bisexual invisibility and the sexual health needs of adolescent girls. LGBT Health. 3(5), 342–349. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2016.0035. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27604053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ard K. L., & Makadon H. J. (n.d.). Improving the health care of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people: Understanding and eliminating health disparities. Boston, MA: The Fenway Institute; Retrieved from https://www.lgbthealtheducation.org/wp-content/uploads/Improving-the-Health-of-LGBT-People.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bluestone J., Johnson P., Fullerton J., Carr C., Alderman J., & BonTempo J. (2013). Effective in-service training design and delivery: Evidence from an integrative literature review. Human Resources for Health. 11, 51 doi:10.1186/1478-4491-11-5. Retrieved from https://human-resources-health.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1478-4491-11-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill S. R., Baker K., Deutsch M. B., Keatley J., & Makadon H. J. (2016). Inclusion of sexual orientation and gender identity in stage 3 meaningful use guidelines: A huge step forward for LGBT health. LGBT Health. 3(2), 100–103. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2015.0136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill S. R., Singal R., Grasso C., King D., Mayer K., Baker K., & Makadon H. (2014). Do ask, do tell: High levels of acceptability by patients of routine collection of sexual orientation and gender identity data in four diverse American Community Health Centers. PLoS One. 9(9), e107104 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0107104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisp C. (2006). The gay affirmative practice scale (GAP): A new measure for assessing cultural competence with gay and lesbian clients. Social Work. 51(2), 115–126. Retrieved from http://www.geneticcounselingtoolkit.com/cases/pedigree/Gay%20Affirmative%20Practice%20Scale%20GAP[1].pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch M. B. (2017a). Creating a safe and welcoming clinic environment. Retrieved from http://transhealth.ucsf.edu/trans?page=guidelines-clinic-environment

- Deutsch M. B. (2017b). Introduction to the guidelines. Retrieved from http://transhealth.ucsf.edu/trans?page=guidelines-introduction

- Flores A. R., Herman J. L., Gates G. J., & Brown T. N. T. (2016). How many adults identify as transgender in the United States? Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute; Retrieved from http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/How-Many-Adults-Identify-as-Transgender-in-the-United-States.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gates G. J. (2015). Comparing LGBT rankings by metro area: 1990 to 2014. Los Angeles, CA: Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law; Retrieved from http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Census2010Snapshot-US-v2.pdf?r=1 [Google Scholar]

- Gates G. T. (2011). How many people are lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender? Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law; Retrieved from http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Gates-How-Many-People-LGBT-Apr-2011.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gates G. J., & Cooke A. M. (n.d.). U.S. census snapshot: 2010. Retrieved from http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Census2010Snapshot-US-v2.pdf?r=1

- Gates G., & Newport F. (2012, October 18). Special report: 3.4% of U.S. adults Identify as LGBT. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/158066/special-report-adults-identify-lgbt.aspx?utm:source=lgbt&utm:medium=search&ut

- Gay & Lesbian Medical Association. (n.d.). Guidelines for care of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients. Retrieved from http://glma.org/_data/n_0001/resources/live/GLMA%20guidelines%202006%20FINAL.pdf

- Green S., Dixon P., & Gold-Neil V. (1993). The effects of a gay/lesbian panel discussion on college student attitudes toward gay men, lesbians, and persons with AIDS (PWAs). Journal of Sex Education and Therapy. 19(1), 47–63. Retrieved from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01614576.1993.11074069 [Google Scholar]

- Health Resources and Services Administration. (2016, March 22). Approved uniform data system changes for calendar year 2016. (Program Assistance Letter No. PAL-2016-02). Retrieved from https://bphc.hrsa.gov/datareporting/pdf/pal201602.pdf

- HealthyPeople.gov. (2016). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, & transgender health: Overview. Retrieved from https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-health

- Human Rights Campaign Foundation. (2016). Healthcare equality index, 2016. Retrieved from http://www.hrc.org/hei

- Institute of Medicine, Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities. (2011). The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64801/ [Google Scholar]

- Kelly P. (2008). Nursing leadership and management (2nd ed.). Clifton Park, NY: Thomson Delmar Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly P. (2012). Nursing leadership and management (3rd ed.). Clifton Park, NY: Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick M. K., Esterhuizen P., Jesse E., & Brown S. (2015). Improving self-directed learning/intercultural competencies: Breaking the silence. Nurse Educator. 40(1), 46–50. doi:10.1097/NNE.0000000000000092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotzbaugh R., & Spencer G. (2015). Cues-to-action in initiating lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender-related policies among magnet hospital chief nursing officers: A demographic assessment. Advances in Nursing Science. 38(2), 110–120. doi:10.1097/ANS.0000000000000069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krehely J. (2009, December 21). How to close the LGBT health disparities gap. Retrieved on from https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/lgbt/reports/2009/12/21/7048/how-to-close-the-lgbt-health-disparities-gap/

- Lim F. A., Brown D. V., & Kim S. M. (2014). Addressing health care disparities in the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender population: A review of best practices. American Journal of Nursing. 114(6), 24–34. doi:10.1097/01.NAJ.0000450423.89759.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makadon H. J. (2011). Ending LGBT invisibility in health care: The first step in ensuring equitable care. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 78(4), 220–224. doi:10.3949/ccjm.78gr.10006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll J., Krieger P., Moreno-Walton L., Lee B., Slaven E., James T., … Heron S. L. (2014). The prevalence of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health education and training in emergency medicine residency programs: What do we know? Academic Emergency Medicine. 21(5), 608–611. doi:10.1111/acem.12368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhill A. L., Mathews J. L., Fearing S., & Gainsburg J. (2014). A transgender health care panel discussion in a required diversity course. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 78(4), 81 doi:10.5688/ajpe78481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainbow Health Initiative. (n.d.). Provider directory. Retrieved from http://mnlgbtqdirectory.org/

- Tagalicod R. (2013). Health IT and quality: Eliminating health disparities. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/eHealth/ListServ_EliminatingHealthDisparities.html [Google Scholar]

- The Joint Commission. (2011). Advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient- and family-centered care for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community: A field guide. Oak Brook, IL: The Joint Commission; Retrieved from http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/LGBTFieldGuide.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Torres C. G., Renfrew M., Kenst K., Tan-McGrory A., Betancourt J. R., & López L. (2015). Improving transgender health by building safe clinical environments that promote existing resilience: Results from a qualitative analysis of providers. BMC Pediatrics. 15, 187 doi:10.1186/s12887-015-0505-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger C. A. (2015). Care of the transgender patient: A survey of gynecologists’ current knowledge and practice. Journal of Women’s Health. 24(2), 114–118. doi:10.1089/jwh.2014.4918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]