Abstract

Rare neurodevelopmental syndromes often present social cognitive deficits that may underlie difficulties in social interactions and increase the risk of psychosis or autism spectrum disorders. However, little is known regarding the specificities of social cognitive impairment across syndromes while it remains a major challenge for the care. Our review provides an overview of social cognitive dysfunctions in rare diseases associated with psychiatric symptoms (with a prevalence estimated between 1 in 1,200 and 1 in 25,000 live births: 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, Angelman syndrome, Fragile X syndrome, Klinefelter syndrome, Prader–Willi syndrome, Rett syndrome, Smith–Magenis syndrome, Turner syndrome, and Williams syndrome) and shed some light on the specific mechanisms that may underlie these skills in each clinical presentation. We first detail the different processes included in the generic expression “social cognition” before summarizing the genotype, psychiatric phenotype, and non-social cognitive profile in each syndrome. Then, we offer a systematic review of the social cognitive abilities and the disturbed mechanisms they are likely associated with. We followed the PRISMA process, including the definition of the relevant search terms, the selection of studies based on clear inclusion, and exclusion criteria and the quality appraisal of papers. We finally provide insights that may have considerable influence on the development of adapted therapeutic interventions such as social cognitive training (SCT) therapies specifically designed to target the psychiatric phenotype. The results of this review suggest that social cognition impairments share some similarities across syndromes. We propose that social cognitive impairments are strongly involved in behavioral symptoms regardless of the overall cognitive level measured by intelligence quotient. Better understanding the mechanisms underlying impaired social cognition may lead to adapt therapeutic interventions. The studies targeting social cognition processes offer new thoughts about the development of specific cognitive training programs, as they highlight the importance of connecting neurocognitive and SCT techniques.

Keywords: social cognition, facial emotion recognition, theory of mind, systematic review, genetics, neurodevelopmental disorders

Introduction

Neurodevelopmental syndromes are genetic abnormalities frequently associated with behavioral and/or psychiatric phenotypes. Notably, these syndromes increase the difficulties in social interactions and present a high risk to develop psychosis or autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) (1–3). While social difficulties are generally associated with several comorbidities of genetic conditions, such as intellectual impairments, facial dysmorphology, speech problems, and psychotic symptoms, the high prevalence of social cognitive disorders recently received a growing interest. The aim here is thus to provide an overview of social cognitive abilities in developmental syndromes associated with psychiatric symptoms and shed some light on the specific mechanisms that may underlie these skills in each clinical presentation.

We focus on syndromes with a psychiatric phenotype (psychosis and/or ASD) and a prevalence estimated between 1 in 1,200 and 1 in 25,000 live births: 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11.2DS) (4–6), Angelman syndrome (AS), Fragile X syndrome (FXS) (7), Klinefelter syndrome (KS), Prader–Willi syndrome (PWS) (8, 9), Rett syndrome (RS), Smith–Magenis syndrome (SMS) (10), Turner syndrome (TS), and Williams syndrome (WS) (11). We first detail the different processes included in the generic expression “social cognition” before summarizing the genotype, psychiatric phenotype, and non-social cognitive profile in each syndrome. Then, we offer a systematic review of the social cognitive abilities and the disturbed mechanisms they are likely associated with. We finally provide insights that may have considerable influence on the development of adapted therapeutic interventions such as social cognitive training (SCT) therapies specifically designed to target the psychiatric phenotype.

Social Cognition

Social cognition is defined as the ability to understand, perceive, and interpret information about other people and ourselves in a social context. This includes abilities such as emotion recognition, theory of mind (ToM), attributional style, and social perception and knowledge (Figure 1). Broadly speaking, social cognition includes a wide range of processes that allow people to rapidly, effortlessly, and flexibly perceive and interpret rapidly changing social information, and respond appropriately to social stimuli. Besides, this ability gives meaning to the actions of others. More specifically, social cognition is an “umbrella concept” that includes many heterogeneous cognitive dimensions, such as emotional information processing, social perception and knowledge, ToM, and attributional bias (12).

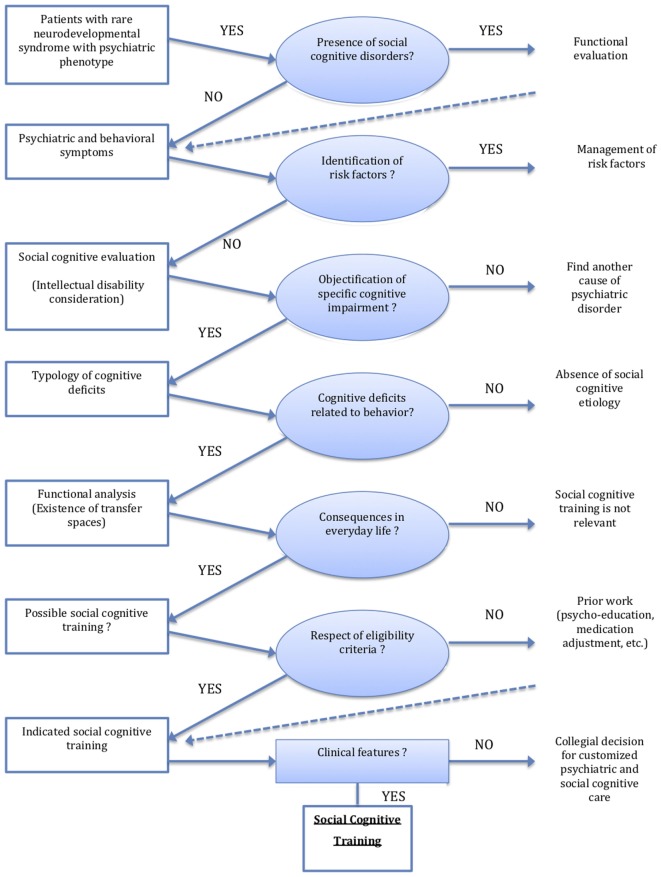

Figure 1.

Organizational decision chart of social cognitive training in rare neurodevelopmental syndromes with psychiatric phenotype.

Emotional Information Processing

Emotional information about others is conveyed by complex signals such as prosody and emotional expressions from the face or the body (13). Regarding emotional expressions, Ekman (14) described six basic emotions (happiness, sadness, fear, disgust, anger, and surprise) that can be easily discriminated from one another depending on different facial patterns (14, 15). Such categorical perception requires the processing of fine face changes and specific observation strategies.

Theory of Mind

An individual has a ToM if he imputes mental states to himself and others. A system of inferences of this kind is properly viewed as a theory because such states are not directly observable, and the system can be used to make predictions about the behavior of others (16–18). This theory comprises two dimensions: cognitive ToM (beliefs, intentions, etc.) and affective ToM (emotional state, knowledge of emotion, etc.) (19, 20). The ToM is subtended by first- and second-order representations. The first-order representation is defined as the ability to understand another person’s mental state. The second-order representation is the ability to understand what one person thinks about another person’s thoughts. These levels are both supported by the primary ability to understand how and why an individual does something (e.g., understanding motor action and eye direction) (16).

Attributional Style

Attribution refers to the way people explain their own and other people’s behaviors (21), but individuals are not objective perceivers and sometimes attribution does not properly match reality. Some individuals suffer from attribution bias, i.e., they systematically over- and under-use the available information, which leads to a misinterpretation of the world they live in.

Social Perception and Knowledge

Social perception refers to the understanding of social roles and rules that typically appear in social situations. Social knowledge is the awareness of the behavior expected in different social contexts and interactions (12). This knowledge consists of social experience, education, and ritualized practices that are not necessarily explicitly communicated. These processes are the basis of an accurate analysis of another person’s intentions, desires, or emotional states; more generally, it is linked to ToM.

Selected Neurodevelopmental Syndromes

The Table 1 presents a summary of the main medical, psychiatric, and social characteristics of the neurodevelopmental syndromes cited in this review.

Table 1.

Summary presentation of the main medical and social characteristics of the neurodevelopmental syndromes cited in this review.

| Syndrome | Chromosome | Prevalence | Medical characteristics | Main characteristics of social behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22q11.2 DS | 22q11.2 | 1 in 2,000–4,000 births (22, 23) | Characteristic facial dysmorphology, mainly congenital heart disease, velopharyngeal insufficiency, cleft palate, neuromuscular problems, hypoparathyroidism, and thymic hypoplasia | Withdrawal [but normal social motivation and adaptive behavior according to Ref. (24)] Difficulties to maintain relationships High risk of development of psychotic disorders (25, 26) |

| Angelman syndrome | 15q11q13 | 1 in 10,000–12,000 births (27, 28) | Microcephaly, epilepsy, feeding problems | High levels of social approach behavior toward familiar (e.g., their mothers) and unfamiliar adults, strong enthusiasm for adult attention (29, 30) Autistic behaviors such as balance and movement problems, manual stereotypy such as hand-flapping (31), absence of eye contact, fascination for certain objects, and intolerance to change (32) Frequent laughter can be caused by a minimal stimulus and is often inappropriate |

| Fragile X syndrome | X | 1 in 1,500 males and 1 in 2,500 females (33) | Characteristic facial dysmorphology. Macroorchidism, hyperextensible metacarpophalangeal joints, curvature of the spine (scoliosis), seizures (epilepsy), heart murmurs | Withdrawal, anxious Autistic behaviors including avoidance of eye contact (34, 35), sensory hypersensitivity, stereotypical behavior, hand flapping, echolalia, and language delay (36, 37) |

| Klinefelter syndrome | X aneuploidy | 1 in 667 births (38) | Tall stature with disproportionally long legs and arms. Hypogonadism, gynecomastia, infertility. Comorbid symptoms such as taurodontism, osteopenia, breast cancer, thyroid dysfunction, and chronic autoimmune disease | High social anxiety levels and reduced social assertiveness (39). But level of social motivation is not impaired (40) Men with a prenatal diagnostic may present with fewer social difficulties, which may be due to an increased prenatal support to the family (40) |

| Prader–Willi syndrome | 15q11–q13 | 1 in 15,000 to 20,000 births (41) | Characteristic facial dysmorphy. Neonatal hypotonia and feeding difficulties. Hyperphagia, obsession with food, hypogonadism | Maladaptive behaviors such as outbursts, self-mutilation, impulsivity, ritualistic behaviors, repetitive conversation topics, and difficulties with routine change |

| Rett syndrome | X | 1 in 10,000 newborn girls (42) | Partial or complete loss of hand skills, apraxia, spasticity, scoliosis, abnormal breathing patterns, and seizures | Atypical socio-communicative pattern that develops prior to the period of regression: the use body movements, gestures, eye gazes, vocalization, and production of words depending on the context (expressing discomfort or happiness, making choices, requesting objects, performing activities, focusing attention, and socializing) (43–45) |

| Smith–Magenis syndrome | 17p11.2 | 1 in 25,000 births (46) | Characteristic facial dysmorphy. Brachycephaly, midface hypoplasia, prognathism, hoarse voice, infantile hypotonia, chronic otitis, sleep disorders | Strong desire for social interaction, good eye contact (47, 48) Maladaptive behaviors such as self-injury (including wrist biting, skin picking and head banging), temper tantrums, body rocking, contrasting with challenging behavior, hyperactivity, insert their hand in their mouth or objects into body orifices, sometimes with public masturbation Stereotypical behaviors including repetitive questions, routine, and the tendency to bring about recurring subjects |

| Turner syndrome | Complete or partial absence of one X chromosome | 1 in 2,000 live female births (49) | Short stature, ovarian failure, sex hormone deficiencies, webbed neck, cardiac malformation, abnormal pubertal development, and amenorrhea with infertility | Shyness, social anxiety, low self-esteem (social acceptance, romantic relationships, etc.), social withdrawal, emotionally less mature than controls (50, 51) [but normal social motivation according to Ref. (52, 53)] Good social knowledge but difficulties to put it into practice in real life, probably due to social anxiety (54) |

| Williams syndrome | 7q11.23 | 1 in 7,500 births (55) | Characteristic facial features. Cardiovascular disease, hyperopia, strabismus, feeding difficulties, hypercalcemia, joint hypermobility | Difficulties making friends, maladaptive behaviors, non-social anxiety, and difficulties in social reciprocity similar to individuals with Autism spectrum disorder (56) Heterogeneous social skills (57, 58) |

Materials and Methods

This systematic review follows the process developed by the PRISMA statement, including the definition of the relevant search terms, the selection of studies based on clear inclusions and exclusion criteria, and the quality appraisal of papers.

Search Strategy

A search of the literature was conducted using the electronic database PubMed and Google Scholar, covering the period between first January 1990 and December 2016 and focusing on articles published in English. Broad search terms were used, including “social cognition,” “theory of mind,” “mind reading,” “mentalizing,” “mentalising,” “emotion recognition,” “emotion perception,” “emotion processing,” “affect recognition,” “affect perception,” “affect processing,” “social knowledge,” “attributional style,” “facial emotion,” “auditory emotion,” “gaze processing,” “body posture,” “social cues” in combination with the diagnostic terms “22q11.2 deletion syndrome” (22q11.2DS), “Angelman syndrome,” “Fragile X syndrome” (FXS), “Klinefelter syndrome” (KS), “Prader-Willi syndrome” (PWS), Rett syndrome” (RS), “Smith-Magenis syndrome” (SMS), “Turner syndrome” (TS) and “Williams syndrome” (WS). Reference lists of the retrieved articles were also manually searched for relevant publications. All articles investigating the perception and/or recognition of affective stimuli (facial expression, prosody, and body language), ToM, social knowledge and attributional style in patients with rare neurodevelopmental syndromes were evaluated. Only studies that involved a behavioral task were included. We excluded from our evaluation the studies that only included neuroimaging data, the studies with non-humans and the reviews, and studies that did not directly assessed social cognition such as studies using only a questionnaire assessing social behavior.

A total of 256 articles were initially identified as potential papers for inclusion. After a comprehensive reading by the first author (Aurore Morel), 136 articles were excluded from the analysis (e.g., studies not focused on behavior or duplicates). A total of 120 papers met the inclusion criteria and were eligible for quality appraisal (40 duplicates).

All titles and abstracts of the identified studies were independently assessed by two authors (Elodie Peyroux and Caroline Demily) for inclusion in or exclusion from the systematic review. Papers were excluded when inclusion criteria were not met (disagreements were resolved by discussion).

Data Analysis

We extracted relevant data from the 132 studies. A meta-analysis of the studies was not feasible given the variations among study designs, social cognitive assessments used, and populations.

A thematic analysis was performed to qualitatively synthesize the data, aiming at identifying specific syndrome patterns. Data were presented in a narrative form. The analytic process was carried on through discussion between the authors (Aurore Morel, Arnaud Leleu, Elodie Peyroux, Emilie Favre, Nicolas Franck, and Caroline Demily).

Patients

We proposed a review analysis, reporting the number of subjects included, the nature of the control population, the statistical method used, and the results obtained for all current published studies (Tables 2–5).

Table 2.

Fourteen studies examining social cognition in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11.2DS).

| Reference | N | Mean age in years (range) | Full scale intelligence quotient (SD) [range] | Comparison group | Social cognition domain (task) | Data analyses | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (59) | 17 | 17.2 | 72.5 (12.7) | Typically developing (TD) | Exploring face | ANOVA | Patients with 22q11.2 spent less time observing the eye and mouth region than controls (p = 0.009) |

| (60) | 50 | 11.00 (6–16) | 65.80 (9.32) [40–94] | TD | Ability to infer first-order false beliefs (the Smarties task and on the Sally–Ann task) Ability to infer second-order false beliefs Cognitive theory of mind (ToM) (strange stories) |

Fisher’s exact test Pearson correlations |

Children with 22q11.2 did not show difficulties on the Smarties task (p = 0.52) and on the Sally–Ann task (p = 0.15) Only younger children with 22q11.2DS showed poorer performance on second-order false-belief tasks and strange stories task (p < 0.02) |

| (61) | 24 | 16.75 (12–21) | 75.88 (14.93) [56–115] | TD | Ability to infer second-order false beliefs Affective ToM |

ANOVA | Children with 22q11.2DS had difficulties to attribute emotions based on circumstances (p = 0.001) |

| (62) | 35 | 18.2 (9–33) | 69.5 (11.3) | TD | Identification of dynamic facial expression (labeling task) | MANCOVA | Individuals with 22q11.2 and controls with typical development and the same age showed similar performance (p = 0.81) But participants with 22q11.2 were slower to recognize emotions (p < 0.01) |

| (63) | 26 | 12.36 (8–15) | 74.19 (11.99) | “Idiopathic” developmental delay (DD) + TD | Exploring face | MANOVA | Participants with 22q11.2DS spent more time looking at the mouth (p = 0.002) |

| (64) | 21 | 14.86 (8–32) | – | Prodromal + schizophrenia family member + low risk | Identification of static facial expressions (labeling task) | Regression analysis | Individuals with 22q11.2DS had difficulties to label emotions (p < 0.0001) |

| (65) | 63 | 13.7 (6–25) | 80.5 (13.7) | 22q11.2DS + TD | Ability to spontaneously attribute mental state (social-attribution task) | ANOVA | In comparison to controls, individuals with 22q11.2DS showed significant impairments in the ability to explain purposeful behavior (intentionality) (p < 0.001) and to describe accurately the events going on in the scene (appropriateness) (p < 0.01) |

| (25) | 31 | 15.9 | – | Healthy control | Cognitive ToM (TASIT task) | T-test | 22qDS participants exhibited impaired performance on task of ToM (p < 0.001) and in recognition of lies (p < 0.001) and sarcasms (p < 0.001) |

| (66) | 15 | 14.67 (9–19) | – | TD | Perception of facial expression (picture-to-picture matching task with morphed face stimuli) | ANOVA | In comparison with control, individuals with 22q11.2DS had more difficulties perceiving anger (p < 0.001), fear (p = 0.049) and sadness (p = 0.028) but not disgust (p = 0.21) and happiness (p = 0.11). They had difficulties to discriminate these facial emotions when they were moderately expressed, as frequently observed in daily life |

| (67) | 17 | 17.44 (12–21) | 72.11 (12.99) | TD | Identification of static facial expressions (labeling task) | ANOVA | The 22q11DS group had significantly more problems correctly identifying the emotions of anger (p = 0.0005), disgust (p = 0.002), fear (p = 0.001) and neutral (p = 0.009) They performed similarly to controls on facial emotions such as happy, surprise and sad (p > 0.05) |

| (68) | 20 | 16.75 (8–21) | 73.75 (13.63) [56–98] | Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) + TD | Identification of static facial expressions (labeling task) Exploring face |

ANOVA | Participants with 22q11.2DS spent more time looking at the mouth compared to both the ASD and TD group (p = 0.02). No main effect of group or interaction were identified for the amount of time spent examining eye region |

| (69) | 49 | 11 | 66.33 (8.6) | TD | Identification of static facial expressions (labeling task) | Mann–Whitney U tests | Individuals with 22q11.2DS had difficulties to label emotions (p < 0.001) in comparison with the TD group |

| (70) | 60 | 10.5 | – | TD | Vocal emotion recognition in stimuli with semantic message (paralanguage test) | Chi-square | No significant differences were found in the emotional perception and processing by paralanguage subtest between the two groups |

| (71) | 29 | 15.7 | 79.52 [35–113] | TD | Identification of static facial expressions (labeling task with morphed image) Cognitive ToM (strange stories) |

Wilcoxon rank-sum tests | Individuals with 22q11.2DS was significantly less accurate in detecting the sadness (p = 4.44 × 10−7), fear (p = 8.0 × 10−4), disgust (p = 6.77 × 10−9), anger (p = 5.95 × 10−7), happiness (p = 5.0 × 10−4), sarcasm (p = 1.16 × 10−6), and sincere (p = 6.0 × 10−4) but not for the surprise (p = 0.3) |

Table 5.

Studies examining social cognition in Williams syndrome (WS).

| Reference | N | Mean age in years (range) | Full scale intelligence quotient (SD) [range] | Mental age (MA), verbal mental age (VMA), and non verbal mental age (NVMA) (SD) [range] | Comparison group | Social cognition domain (task) | Data analysis | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (93) | 27 | 17.41 (5.33–43.66) | 47 (19) [18–84] | MA 5.75 (1.1) [3.78–8.66] | Typically developing matched on mental age (TDMA) + typically developing matched on chronological age (TDCA) | Cognitive theory of mind (ToM) | ANOVA | Individuals with WS attributed less negative intentions than TDMA and TDCA groups (p < 0.001) |

| (57) | 19 | 21.5 (7.16–38.83) | – | – | TDCA + TDVA | Identification of complex emotions (RMET) |

T-test ANOVA, Tukey post hoc tests |

Adults with WS perform at similar level than TDCA group when identifying whether the actors are “deciding” (p = 0.553), “not sure” (p = 0.279), or “worried” (p = 0.553) They were less accurate at identifying “ do not trust ” in comparison to TDCA group (p = 0.001) and TDVA group (p = 0.008), “disapproving” in comparison with TDCA group (p < 001), “relieved” in comparison to TDCA group (p = 0.013) |

| (94) | 24 | 32.36 (15.4–56.9) | 65 (7.10) [50–80] | – | Typically developing (TD) | Vocal emotion recognition in multisensory emotional information (paralanguage test) | T-test | Between-group differences in performance with the emotionally congruent multisensory (visual and vocal) did not reach the adjusted significance level (p = 0.07). But the TD group outperforming the WS group with the emotionally incongruent audiovisual stimuli (p < 0.001) and the unimodal auditory stimuli (p < 0.001) |

| (95) | 12 | 11.4y (9.6–13.9) | – | – | Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) + TD | Vocal emotion recognition in stimuli without semantic message (paralanguage test) | ANCOVA | No between-group differences were found (p > 0.065) |

| (96) | 8 | 27.8y (18–42) | – | – | DD + TD | Vocal emotion recognition in stimuli without semantic message (paralanguage test) | ANOVA T-test |

The TD group outperforming the WS group (p = 0.004). The interaction effect was due to the WS group exhibiting lower recognition accuracy for negative stimuli (p = 0.001), while no between-group differences were in evidence for the processing of the positive stimuli (p =0.73) |

| (97) | 21 | 24.0 (12–40) | – | – | DD + TD | Identification of static facial expressions (emotion is associated with congruent or non congruent evocativ music) Vocal emotion recognition in multisensory emotional information (paralanguage test) |

ANOVA | Emotionally evocative and congruent music facilitated the ability of participants with WS, DD, or TD to process emotional facial expressions (p = 0.03) |

| (98) | 57 | 9.24 (6.00–12.74) | 72.93 (15.17) [40–97] | – | – | Ability to infer first-order false beliefs | WS patients had difficulties to understand false beliefs | |

| (99) | 12 | 8.10 (6.1–15.3) | – | VMA 5.8 (1.11) [3.4–9.3] | AUT (autism group) + TDVMA | Identification of static facial expressions (labeling task) | ANOVA | Individuals with WS showed emotion recognition levels similar to controls with the same mental age or individuals with developmental disabilities |

| (100) | 25 | 9.5 (6–15) | 54.7 (8.95) | – | – | Identification of static facial expressions (labeling task) | Individuals with WS recognized facial affect at an appropriate developmental level | |

| (101) | 20 | 12.25 (5.6–23.58) | – | MA 5.58 (0.75) [4.25–6.83] | DS + TDCA + TDMA | Identification of static facial expressions (labeling task) | ANOVA (pair-wise comparisons with Bonferroni correction) | In emotion recognition task, no significant differences were found between participants with WS and TDMA group but participants with WS performed significantly lower than TDCA group (p < 0.001). the DS group performed significantly lower than the WS (p ≤ 0.001) |

| (102) | 11 | 30.6 | 66.4 (11.5) | – | TD | Processing of egocentric gaze | T-test | No difference in accuracy when WS and TD groups were compared (p < 0.057). However, WS participants were slower than controls (p < 0.0001) in determining the gaze direction |

| (103) | 47 | 19.49 (12.1–32.4) | 69.08 (12.2) [51–100] | – | Learning disability + TD | Identification of static facial expressions (labeling task) Vocal emotion recognition in stimuli with semantic message (paralanguage test) |

ANCOVA | In labeling task and paralanguage test, WS group was significantly less accurate in recognition of sadness, anger and fear (p < 0.0001) than TD group. No difference is revealed between WS and learning disability groups |

| (104) | 20 | 16.13 (5.33–43.67) | – | – | DS + TDCA + TDMA | Identification of static facial expressions (labeling task) | ANOVA | Individuals with WS showed emotion recognition levels similar to TDMA group (p > 0.1). WS groups outperformed the DS group (p < 0.05). And TDCA group outperformed WS group (p < 0.01) |

| (105) | 31 | 17.02 (5.33–43.67) | – | MA 5.65 (1.31) [3.58–9.33] | TDCA + TDMA | Ability to infer first-order false beliefs (non-verbal picture-sequencing task) | ANOVA | The WS group performed significantly below the TDMA group on the false belief stories (p < 0.01). These groups performed similarly on all other story types (understanding of pretense and intent). TDCA group performed significantly better than the WS group and TDMA group on all story type (p < 0.01) |

| (106) | 16 | 25.14 (11.42–50.58) | 61 (15) [38–84] | – | TDMA | Identification of static facial expressions (labeling task) Exploring face |

ANOVA | Individuals with WS showed emotion recognition levels similar to TDMA group: no significant main effect for group was revealed (p > 0.1) The WS group spent significantly more time looking at the eyes than TD controls (p < 0.05) but the groups spent a similar amount of time looking at the nose (p > 0.1) and the mouth (p = 0.1) |

| (107) | 15 | 10.41 (6.0–15.83) | – | VMA7:2 (20) | ASD + TDVMA match with WS + TDNV match with WS + VMA match with ASD + TDNV match with ASD | Perception of facial expression (picture-to-picture matching task) | T-test | Participants with WS were more accurate when perceiving happiness, sadness, anger, and surprise relative to TDVMA (p < 0.05) and TDNV (p < 0.01) group, who did not differ |

| (108) | 14 | 15.16 (8.75–28.0) | – | – | ASD + TDNV matched individually with WS + TDNV matched individually with ASD | Exploring face | T-test | Individuals with WS fixated faces for longer than participants who were developing typically (p < 0.001) |

| (109) | 15 | 13.50 (8.66–28.0) | – | – | ASD + TDNV matched individually with WS + TDNV matched individually with ASD | Processing of allocentric gaze | T-test | In comparison with TDNV, participants with WS had difficulties to interpret eye-gaze direction (p < 0.05) |

| (110) | 29 | 14.7 (7–27) | 57.8 (12.3) [40–93] | MA 8.3 (2.9) [4–17] | TDMA +TDCA | Identification of static facial expressions (labeling task) | ANOVA | No such group differences were found for photographs of real faces (WS vs. TDMA, p > 0.05; WS vs. TDCA, p > 0.05) |

| (111) | 19 | 14.4 (7–26) | 57.5 (11.0) | MA 8.3 (3.5) VMA 9.3 (3.5) PMA 7.9 (2.7) |

TD | Cognitive ToM (strange stories) | ANOVA (turkey test) | WS group were significantly less accurate on the visual than on the verbal modality (p < 0.001) |

| (112) | 19 | 13.7 (5.1–30.0) | 63.3 (12.33) | MA 6.5 (1.9) [4.1–11.2] | TDMA + TDCA | Processing of motor action | ANOVA | The WS and TDMA groups differed from performance of the TDCA group (p = 0.015 and p = 0.025, respectively). Most interestingly both the WS and the TDMA groups were significantly aided by the presence of contextual cues (p < 0.001), while the presence of contextual cueing brought no variation in performance within the TDCA group (p = 0.063) |

| (113) | 16 | 12.58 (5.08–22.66) | 64.9 (13.50) [44–87] | MA 6.5 (1.33) [4.1–11.2] | ASD + TDMA + TDCA | Processing of motor action | ANOVA | In the presence of context cues, children with WS were as accurate as children with the same chronological age and children with the same mental age in determining why others perform specific motor actions. Amount of errors made by all groups did not differ |

| (114) | 29 | 19.1 (13.1–32.1) | 68.1 (12.8) [45–94] | Learning/intellectual disability + TDCA | Identification of dynamic facial expression (labeling task) | ANOVA | Participants with WS were less accurate than controls with TDCA (p < 0.001). But they were as accurate as participants with intellectual disabilities (p = 0.87) | |

| (115) | 21 | 7.16 (4.5–8.58) | 68 (12) [43–93] | VMA 4.91 (1.33) [3.1–8.2] | Prader–Willi syndrome (PWS) + NMR | Perception of facial expression (picture-to-picture matching task) Ability to infer first-order false beliefs (similar to the Sally–Ann task) Affective ToM (explanation of action task) |

Chi-square test | On the false belief question, more of the MRU and PWS children passed than did the WMS children (p < 0.06). The three groups performed at a similar level in picture-to-picture matching test and the explanation of action task |

| (116) | 30 | 9.91 (5.00–17.08) | – | – | TD | Ability to infer first-order false beliefs (task similar to the Sally–Ann task but presented in video and without narrative) | Fisher’s exact test | More participants in the WS group failed the false belief question in contrast to the TD group (p = 0.001) |

Table 3.

Studies examining social cognition in Fragile X syndrome (FXS).

| Reference | N | Mean age in years (range) | Full scale intelligence quotient (SD) [range] | Mental age (MA), verbal mental age (VMA), and non verbal mental age (NVMA) (SD) [range] | Comparison group | Social cognition domain (task) | Data analysis | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (72) | 30 | 20.93 (16.05–25.33) | 67.78 (20.73) [40–119] | – | Comparison group (idiopathic developmental delay, intellectual disability, or learning disability) | Processing of egocentric gaze | ANOVA | Individual with FXS performed at the same level than patients with similar general cognitive abilities and autism symptoms (p = 0.53) |

| (73) | 28 | 11:2 (7–15) | – | VMA 6.91 (1.75) [4.1–10.9] | Down syndrome (DS) | Ability to infer first-order false beliefs (Sally–Ann task and the appearance-reality task) | Chi-square test | Children with FXS and individuals with DS performed at a similar level During the Sally–Ann task (p = 0.77) and the appearance-reality task (p = 0.91) |

| (74) | 22 | 47.91 (18–69) | 105.18 (10.5) | – | Typically developing (TD) (from FXS families) + TD (from general population) | Identification of static facial expressions (labeling task) Identification of complex emotions (RMET) |

ANOVA | In comparison with TD group, individuals with FXS were less proficient in discriminating basic emotion (p = 0.02) and complex emotion (p = 0.008) |

| (75) | 13 | 19.70 (6.60–34.19) | – | – | Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) | Spontaneous perception of facial expression (oddball paradigms in conjunction with a measure of preferential looking) | t-test | Individuals with FXS or autism looked significantly longer at disgusted faces compared to neutral faces (FXS: p = 0.001; ASD: p = 0.001) |

| (76) | 8 | 12.5 (10.25–14.16) | 45.3 (3.2) [40–49] | VMA 6.58 (1.66) [4.83–9.50] | Intellectual disability of unknown etiology | Ability to infer first-order false beliefs (the Smarties task) | Chi-square test | Individuals with FXS were less accurate in the Smarties task (p < 0.05) |

| (77) | 15 | 13.66 | – | VMA: 6.11 (2.0) NVMA: 6.0 (1.3) |

FXS-A + intellectual disability group | Ability to infer first-order false beliefs (Sally–Ann task) | ANOVA | Individuals with FXS or FXS-A were less accurate in the Sally–Ann task than the Intellectual Disability group (p = 0.009) |

| (78) | 10 | 16.4 (9.7–24.0) | 91 (16.2) [75–124] | – | TD | Identification of static facial expressions (labeling task) | T-test | Individuals with FXS were less proficient in discriminating neutral faces (p = 0.048), sadness (p = 0.070) and scrambled face (p = 0.016) than TD group |

| (79) | 19 | 30.47 (18–40) | 92.2 (15.3) | – | Obligate carrier + TD | Perception of facial expression (picture-to-picture matching task) | ANCOVA | Fragile X women do not demonstrate a deficit in emotion perception |

| (80) | 16 | 24.8 (12.1–56.1) | 64 (13.7) [51–96] | MA 8.4 (3.8) [6.0–21.1] | Typically developing matched on mental age (TDMA) + typically developing matched on chronological age (TDCA) | Identification of static facial expressions (labeling task) | ANOVA | FXS group performing significantly worse than both TDCA (p = 0.013) and TDMA (p = 0.044) group in their ability to recognize anger. They were also significantly worse at recognizing neutral expressions compared to TDMA group (p = 0.032) |

| (81) | 15 | 41.80 (17–66) | 36.60 (7.74) | – | Control | Identification of static facial expressions (labeling task) | ANOVA | No significant differences were found in the emotional perception and processing by paralanguage subtest between the two groups |

| (37) (first study) | 14 | 10.34 | – | VMA 5.72 (0.93) [3.9–6.9] | DS + TDMA | Perception of facial expression (picture-to-picture matching task) | ANOVA | No group difference in the ability to recognize emotion from facial expression (p = 0.110) |

| (37) (second study) | 18 | 8.16 (4–14) | – | – | DS + intellectual disability of unknown etiology | Perception of facial expression (picture-to-picture matching task) | Fisher exact test | No group difference in the ability to recognize emotion from facial expression |

| (82) | 13 | 15.5 | 61.0 (14.8) | – | Developmental delay (DD) + TDCA | Processing of egocentric gaze | MANOVA | Significant differences in task accuracy were revealed between the TD group and other groups (p = 0.02 and p = 0.03 vs. DD; p = 0.001 vs. FXS) but not between the DD and FXS groups (p = 0.99 for all) |

| (83) | 12 | 20.6 (12.1–38.1) | 64 (14.7) [52–96] | MA 9.0 (4.2) [6.1–21.1] | TDMA + TDCA | Identification of static facial expressions (labeling task) | ANOVA | FXS group performing significantly more poorly than both control groups when recognizing disgusted (TDMA p < 0.001; TDCA p = 0.001) and neutral (TDMA: p = 0.035; TDCA: p = 0.015) Facial expressions. TDCA group was significantly better at recognizing fearful facial expression compared to the FXS (p = 0.001) and (younger) TDMA (p = 0.001) groups |

| (84) | 15 | 11.75 | – | MA 4.08 (1.08) | DS + non-specific intellectual disability + TD | Perception of facial expression (picture-to-picture matching task) | ANOVA | No obvious deficit in basic emotion perception was reported in FXS group |

Table 4.

Studies examining social cognition in Turner syndrome (TS).

| Reference | N | Mean age in years (range) | Full scale intelligence quotient (SD) [range] | Mental age (MA), verbal mental age (VMA), and non verbal mental age (NVMA) (SD) [range] | Comparison group | Social cognition domain (task) | Data analysis | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (85) | 26 | 30.58 | – | – | Typically developing (TD) | Identification of static facial expressions (labeling task) Ability to spontaneously attribute mental state (social-attribution task) |

T-test ANOVA |

TS women are less accuracy in recognition of fear (p < 0.05) and sadness (p = 0.052) than TD group TS women being less accurate in describing the animations than TD women (p = 0.05) |

| (86) | 51 | 25.1 (15–44) | – | – | Partial X chromosome deletion + TD | Identification of static facial expressions (labeling task) | MANOVA | Children and women with TS showed a specific impairment for the recognition of fearful (p < 0.0001) and angry faces (p < 0.006) |

| (87) | 14 | 10.1 (6.92–12.92) | 90.43 (12.74) | – | TD | Identification of static facial expressions (labeling task) Affective theory of mind (NEPSY-II) |

ANOVA | Girls with TS were significantly less accurate in the classification of fearful faces compared with TD controls (p = 0.007), however, did not differ in accuracy for the other emotions (happy: p = 0.073, neutral: p = 0.106, scrambled: p = 0.179) |

| (88) | 23 | 24.6 (18–36) | – | – | TD | Identification of static facial expressions (labeling task) | ANOVA | Fear and anger were significantly less well recognized by women with TS than controls: for fear (p < 0.01); for anger (p < 0.01) |

| (89) | 18 | 32.6 (18–63) | 104.8 (16.3) | – | TD | Identification of static facial expressions (labeling task) | MANOVA | The TS group were significantly impaired in recognizing fear relative to control females, p < 0.013. None of the other emotions showed significant difference between the two groups |

| (90) | 40 | 25.44 (19–33) | 90.68 (9.30) [75–106] | – | Noonan syndrome + TD | Identification of dynamic facial expression (labeling task) | ANOVA | The mixed between-within subjects ANOVA revealed no significant effect of Group, indicating that the three groups did not significantly differ in accuracy of emotion perception |

| (91) | 71 | 27 (17–50) | 96 (9) | – | TD | Identification of static facial expressions (labeling task) | ANOVA | In comparison with TD group, women with TS showed a specific impairment for the recognition of fear (p = 0.001) and angry (p = 0.001) faces |

| (92) | 94 | 31.2 | 98 (10) | – | Women with premature ovarian failure + TD | Identification of static facial expressions (labeling task) | ANCOVA | The TS group had difficulty to recognize “anger” (p = 0.005), but no “happy,” “sad,” “fear,” “surprise,” and “disgust” |

Results

The large majority of studies assessed either emotion recognition or ToM whereas fewer studies documented attributional style and social knowledge. Moreover, in some area of social cognition, very few studies or no study at all were available for some syndromes, especially AS, RS, and SMS.

Emotional Information Processing

Recognition of Facial Emotion

Basic emotions defined by Ekman (14), namely joy, sadness, anger, fear, and surprise, are the first emotions recognized in faces by children with typical development (117). No obvious deficits in basic emotion perception were reported in females with FXS (37, 79, 81, 84). However, males with FXS looked significantly longer at disgusted faces compared to neutral faces (75), with more difficulties to recognize sadness and fear (83). The same pattern of results was revealed in children with ASD. By contrast, individuals with RS spend less time than controls exploring key facial features (eye, nose, and mouth) for all emotions (118) and have difficulties to recognize emotional expressions (happiness, fear, and sadness) in general. These results may be due to increased attentional or informative value of negative over neutral (and positive) expressions (75).

People with 22q11.2DS have difficulties to discriminate facial emotions when they are moderately expressed (66), which can explain major deficits in social interactions, especially during childhood. Moreover, they have more difficulties to perceive negative emotions such as anger, fear, and sadness and to label emotions (64, 69, 71) while happiness, sadness, and surprise recognition seems efficient (59, 67, 68). A recent study using the CANTAB ERT test (morphed images with fast cover up times to avoid ceiling effects) showed that 22q11.2DS patients are significantly less accurate in detecting sadness and happiness (71). The same results are observed in males with FXS (73, 74, 78, 80, 83, 119).

Patients with WS showed emotion recognition levels similar to controls with the same mental age or individuals with developmental disabilities (99–101, 104, 106, 107, 110, 114). They are more accurate in perceiving happiness, sadness, anger, and surprise (107) but perform more poorly on auditive stimuli for all emotions except for happiness, which seems relatively surprising considering the classical hyperacusis associated with the syndrome (103). Abnormalities in auditory processing in WS seem to be restricted to the perception of negative affective vocalizations, such as scream or gasp (96). However, children with WS had no difficulty to recognize vocal emotions compared to controls (94, 95). Emotional information can be transmitted via both visual (e.g., facial expressions and gestures) and auditory (e.g., affective prosody) channels. In social interactions, both channels are competing and require the integration of relevant multisensory emotional information. When identifying facial affects, patients with WS are as accurate as controls in both congruent and incongruent conditions. But they are less efficient when identifying non-social affects (97). These results confirmed that emotionally evocative music facilitates the ability of patients with WS to recognize emotional faces. They spend more time staring at the salient features of the face—particularly the eyes (106, 108). Interestingly, the ability to discriminate and match faces with emotions was assessed in children with WS syndrome compared to PWS syndrome, or a non-specific intellectual deficiency. The three matched groups performed at a similar level (115) without significant correlation between chronological age (CA) and performance on face perception tasks (107). Overall, neurocognitive deficits do not seem to be the only explanation of expression recognition impairments across syndromes, as illustrated in TS (88).

Adults with WS demonstrated a normal level of performance in the identification of emotions in unimodal conditions with face stimuli alone and in congruent face-voice multisensory contexts. However, they are less accurate to identify emotions in unimodal conditions with vocal emotions alone and even worse in multisensory incongruent stimuli conditions (95, 98). This difference seems to be highly specific and central to understand the hypersociability of WS (Table 1). Patients with WS may be specifically attracted by facial information, decreasing their attention to vocal information. Interestingly, when adults with WS are asked to identify complex mental states (such as worry, disinterest, etc.) from the whole dynamic face, their performance is similar to controls matched on CA (57). However, they have difficulties with “relief” and “distrust,” which may be related to hypersociability.

The deficit is more pronounced in PWS and WS, with difficulties to recognize all basic emotions (8, 99, 101). A global emotion identification impairment was documented in 22q11.2DS, FXS, PWS, and WS but the recognition of happiness seems preserved in these syndromes (101). Regarding the recognition of complex emotions, patients with PWS are less efficient than intelligence quotient (IQ)-matched individuals with WS. This result is consistent with the distinct behavioral symptoms associated to these syndromes (complex psychological disorder with maladaptive behaviors vs. frequent hypersociability).

During a task assessing the recognition of anger, fear, disgust, or sadness, individuals with KS were less accurate in recognizing angry faces, unlike other facial expressions (120). Children and women with TS show a specific impairment for the recognition of fearful and angry faces, both when the stimulus is a whole face or the upper face only (85–89, 91, 92). More specifically, in TS, fear recognition is significantly weaker compared to other emotions, including anger (88), with difficulties to correctly identify affect tones (91). In a study using dynamic facial expressions of different emotional intensities, patients with TS, 22q11.2DS and controls did not show any deficit in recognizing fear (62, 90). But patients with 22q11.2 are slower to recognize emotions (62) with a normal level of emotion recognition in auditory stimuli (70). By contrast, dynamic stimuli in WS do not change the accuracy of emotion recognition (114).

During an emotion recognition task using photographs, patients with 22q11.2 (59) spent less time than controls observing the eye region, as observed in FXS and ASD. They spent more time looking at the mouth (63, 68), which may explain why they have less difficulty to recognize happiness, surprise and, to a lesser extent, disgust. This result is correlated with the high prevalence of ASD in 22q11.2DS and FXS. By contrast, women with TS stare longer at the mouth, but only when looking at fearful faces. This result suggests a possible mechanism for selective fear deficit (89) across syndromes. Facial emotion recognition impairment may be related to an atypical observation of faces (121). Fewer fixations on the eyes region are related to difficulties to recognize specific emotions. This deficit is a core symptom in ASD controls who stare longer at the mouth for joy, fear, and disgust; at the eye for sadness; and at the eye and nose for anger (122).

ToM in Developmental Syndromes With Psychiatric Phenotype

Ability to Infer False-Belief in Others

An important mechanism of ToM is the ability to understand that other people’s beliefs or representations about the world may differ from reality.

Children with 22q11.2 did not show major difficulties in ToM tasks (60). When it comes to PWS and WS, children had difficulties attributing mental states and understanding first-order beliefs (98, 116, 123). These results were confirmed in a non-verbal picture-sequencing task, but with a preservation of the understanding of intention, social script knowledge, and physical cause-and-effect reasoning (105). These results suggest that language abilities do not influence performance on ToM in WS (116), considering the heterogeneity of the process in the syndrome (105).

Patients with FXS are less accurate in ToM tasks (76, 77) and perform at a similar level than individuals with Down syndrome (DS) (73, 74) or ASD (77), with a limited impact of autistic symptoms (124). Altogether, these findings suggest that a ToM disorder in FXS may not result solely from the high comorbidity of ASD (77).

Children with WS, PWS, or a non-specific intellectual deficiency, perform at a similar level in standard ToM tasks (115, 125). However, children with PWS had specific difficulties to attribute second-order beliefs (123, 126).

Interestingly, 22q11.2DS seems specifically associated with a poor performance on false-belief tasks (60, 61), this deficit being highly correlated with psychotic symptoms.

Ability to Infer Mental States in Others

Children with 22q11.2 seem to have difficulties to link contextual and social relevant cues when the scene is visually complex (61) or based on circumstances (61). This deficit may be related to attentional and visuospatial disorders and requires families and therapists to clearly verbalize emotions during social interactions. Moreover, the comprehension of misunderstanding, persuasion, pretending, sarcasm, and white lie seems impaired in 22q11.2DS (25, 60, 71). These findings suggest that a cognitive ToM disorder causes a delay rather than a deficit (60). From this perspective, impairments in the spontaneous attribution of seducing, mocking, playing with one another, getting frightened, or elated mental states to abstract visual stimuli were reported in 22q11.2DS (65), suggesting that gaze direction is also a weakness in the syndrome (60).

As expected, patients with WS were proficient during a verbal task (111, 126) but their performance decreased when the ToM task was presented on a visual medium (111) with difficulties inferring mental states from visual cues, especially for negative intentions (93) and gaze direction (109). These results suggest that they may present a positive bias in the interpretation of social cues. An impaired social-perceptual ability may play a role in increased approachability and a deficit in the processing of basic social cues may have possible repercussions on ToM. The ability to observe and recognize other people’s actions contributes to understand goals and intentions (127) and may help people with WS improve their recognition of action process (113). Indeed, in the presence of context cues, children with WS were as accurate as controls (112, 113).

Overall, patients with 22q11.2DS, FXS, or WS had difficulties determining whether someone is looking at them or elsewhere (60, 82, 102, 128) but individuals with PWS seem to yield scores within the normal range (129). When patients with FXS were asked to judge the direction of eye gazes (direct or averted), they performed at the same level than patients with similar general cognitive abilities and autism symptoms (72), and patients with a developmental delay (82). Complex emotion recognition requires knowledge and analysis of interpersonal relationships, unlike basic emotion recognition. Thus, further research on the potential dissociation between the recognition of complex mental states and basic emotions, and the influence of the nature of the stimuli (static or dynamic) is needed.

Discussion

Interventions and Perspectives

This systematic review shows that social cognition deficits are present in neurodevelopmental disorders at different levels and remain strongly correlated with psychiatric phenotype. Emotion recognition and ToM skills impairments seem to be a core deficit in rare developmental syndromes, otherwise associated with psychosis and ASD. Although more research needs to be done to assess social cognition phenotypes in these syndromes, it is crucial to develop and evaluate appropriate therapeutic interventions. In this section, we briefly discuss therapeutic approaches and present future keys to improve social deficits in that indication.

In daily life, facial expressions are typically embedded in a rich context with many distractors (e.g., noises and visual stimuli) and social information from multiple sensory channels (e.g., prosody, gestures, and change in facial expression). Therefore, social interactions necessitate fast and efficient cognitive skills. They include the ability to identify visual and spatial relationships in emotion recognition, to integrate and manipulate such perceptions, to select relevant information, to inhibit irrelevant stimuli and alternate between several sensitive channels. Emotion recognition is also a complex process involving visual attention (130), visuospatial abilities (130), working memory (131), divided attention and executive functions (132). As a consequence, improvement of these functions may have a positive impact on social cognition and behavior. Visuospatial and visuoperceptual skills play a key role in everyday life. Visual information and complex visual stimuli are analyzed with a complete unawareness of the visuoperceptual process or the complexities of the stimuli involved. This process becomes conscious in a context of learning. Repetition and familiarity enable a more spontaneous approach and turn the conscious and effortful process into an automatic one. If this ability is impaired, many types of deficits can occur, ranking from a failure to process the basic elements of a visual stimulus (i.e., colors, lines, and orientation) to more complex and integrative features, such as object identification, faces, or familiar scenes. These deficits can include social cognition defects, especially in the area of facial emotion recognition, acquired slowly during childhood and reach adult levels in late adolescence (133).

Currently, two programs, named “Cognitus & Moi” (Cognitus & Me) and “Vis-à-Vis” have considered the link between neuropsychological functions and social cognition (facial emotion recognition). “Cognitus & Moi” is a cognitive remediation program with SCT, designed for 5- to 13-year-old children with developmental disorders. The program is specifically focused on attentional, visuospatial functions and emotion recognition (134). It involves a variety of exercises in a paper and/or pencil (n = 30) or a computerized format (n = 29) and a strategy coaching approach. “Vis-à-Vis” is a computerized training program based on a trial-and-error approach. It can be performed at home with parents and targets social cognition difficulties and working memory (135).

The ability to explore face efficiently develops during childhood. The eyes, nose, and mouth are the preferred attentional targets in facial exploration (121). These facial features play an important role in perception and recognition of emotion. However, the visual exploration developed by individuals with neurodevelopmental syndrome is mainly different, with a lack of eye contact according to a specific pattern previously observed in ASD. Individuals with neurodevelopmental syndrome may benefit from educational solutions targeting this impairment. In that regard, an important point is that dynamic information facilitates the perception of facial expressions (136, 137). Individuals with autism appear to benefit from slow dynamic information when categorizing emotional expressions (138). Considering the possibility of overlap between children with neurogenetic disorders and children with typical ASD (139), the question of a similar benefit in rare diseases should also be addressed in the future. More generally, the beneficial effect of motion may play a role in therapeutic intervention.

Some current treatment plans which are based on phenotype rather than etiology may be adapted for individual with neurodevelopmental syndrome.

For example, considering the well-established association between 22q11.2DS and schizophrenia, SCT, a program based on the cognitive enhancement therapy developed for individuals with schizophrenia (140) may be of interest in 22q11.2DS. This program targets general and high-level social skills such as the ability to practice calming techniques, to identify the main idea in a conversation, to determine expected behaviors in different situations (social perception and social knowledge), or to clearly express one’s own thoughts (ToM) (140).

It is necessary to define strengths and weaknesses of each participant and the exact nature of deficits. Indeed this review highlights the implication of different cognitive processes involved in social interaction deficits, which appear to have different effects across syndromes (Tables 6 and 7). Here, we show that social cognition impairments are not uniquely caused by syndrome comorbidities such as IQ. Understanding the differences in the social cognitive abilities may become a distinctive clinical tool to develop special trainings. In several cases, the severe cognitive impairment associated with rare diseases necessitates individual adaptation of therapeutic interventions. Individual may present severe limitations in their ability to communicate through speech and gestures. Single case reports have demonstrated that patients can develop communicative skills and social cognition, particularly affective and cognitive ToM with appropriate interventions. For example, communication by composing words on an alphabetic table may be improved by training communicative skills in RS (141). With a training focused on emotion, discrimination of facial emotion (joy, sadness, and anger) may be improved in RS (142). Moreover, although patients do not develop functional verbal skills, the eye-tracking technology has increased the possibilities to understand patients (143) and facilitated the access to augmentative and alternative communication (144–146).

Table 6.

Emotion processing among rare neurodevelopmental syndrome.

| 22q11.2DS | Fragile X syndrome | Klinefelter syndrome | Prader–Willi syndrome | Rett syndrome | Turner syndrome | Williams syndrome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic facial emotion perception | Deficit in anger, fear, and sadness perception in comparison with typically developing matched on chronological age (TDCA) participants. No deficit in disgust and happiness perception | No obvious deficit in basis facial emotion recognition in comparison with TDCA participants | Not deficit in basis facial emotion perception compared to participants with WS | Not deficit in happiness, sadness, anger. and surprise perception [typically developing matched on mental age (TDMA)] | |||

| Spontaneous perception of facial expression | Not deficit in happiness and disgust perception in comparison with typically developing (TD) participants | Deficit in happiness, sadness, and fear perception in comparison with TDCA participants | |||||

| Basic static facial emotion identification | Deficit in fear, anger, disgust happiness, and sadness identification in comparison with TDCA participants | Deficit in anger, sadness, and disgust identification in comparison with TDCA participants | Specific deficit in anger identification | Deficit in all basic emotion identification in comparison with TDCA participants | Specific deficit in fear and anger identification | Deficit in all basic emotion identification in comparison with TDCA participants; no deficit in basis facial emotion identification in comparison with TDMA participants | |

| Basic dynamic facial emotion identification | Not deficit in basic dynamic facial emotion identification in comparison with TDCA participants | Not deficit in fear identification | Deficit in all basic emotion identification in comparison with TDCA participants | ||||

| Complex facial emotion identification | Deficit in complex facial emotion identification (TD) | Deficit in complex facial emotion identification (TD) | Deficit in complex facial emotion identification (WS) | Deficit in static complex facial emotion identification but no deficit in dynamic facial emotion (“deciding,” “not sure,” and “worried”) identification in comparison with TDCA participants | |||

| Emotion recognition in auditory stimuli | Not deficit emotion recognition in auditory stimuli in comparison with TDCA participants | Deficit emotion recognition in auditory stimuli in comparison with TDCA participants | Deficit in all emotion recognition except happiness in comparison with TDCA participants |

Table 7.

Theory of mind among rare neurodevelopmental syndrome.

| 22q11.2DS | Fragile X | Prader–Willi | Turner | Williams | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ability to infer first-order false-belief | Deficit in first-order false-belief inferring in comparison with typically developing matched on chronological age (TDCA) participants | No deficit in first-order false-belief inferring compared to participant with DS | Deficit in first-order false-belief inferring in comparison with TDCA participants but no deficit compared to participants with WS or non-specific mental retardation | Deficit in first-order false-belief inferring in comparison with TDCA participants, but no deficit compared to participants with Prader–Willi syndrome (PWS) or non-specific mental retardation | |

| Ability to infer second-order false beliefs | Deficit in second-order false-belief inferring (for only younger participants) in comparison with TDCA participants | Deficit in second-order false-belief inferring in comparison with TDCA participants but no deficit compared to participants with WS or non-specific mental retardation | Deficit in second-order false-belief inferring in comparison with TDCA but no deficit compared to participants with PWS or non-specific mental retardation | ||

| Affective theory of mind (ToM) | Deficit in affective ToM in comparison with TDCA participants | No deficit in ToM affective compared to participants with WS or non-specific mental retardation | Deficit in affective ToM in comparison with TDCA participants | No deficit in affective ToM compared to participant with PWS or Nons specific mental retardation | |

| Cognitive ToM | Deficit for only younger participants in cognitive ToM in comparison with TDCA participants | Deficit in cognitive ToM in comparison with TDCA participants | Not deficit for a verbal task [typically developing (TD)] but deficit with a visual task (TD) | ||

| Ability to spontaneously attribute mental state | Spontaneously attribute mental state disability in comparison with TDCA participants | Spontaneously attribute mental state disability in comparison with TDCA participants | Spontaneously attribute mental state disability (not comparison group) |

Face recognition and ToM have an important role in social problem solving (14, 147, 148). These capacities allow to understand and interpret other’s emotion (149). In the social interaction, recognition of expressions leads to adapt behavior (150, 151).

Limitations

This systematic review highlights some limits. Some rare syndromes received only little interest, particularly AS, KS, RS, and SMS. The lack of results regarding some areas of social cognition in these syndromes must be interpreted with caution, as the number of published studies is limited. Furthermore, very few studies have directly compared patients considering anxiety levels. Moreover, psychiatric diagnosis has not been considered and very few studies have proposed to establish a link between social cognition and behavior in rare neurodevelopmental syndromes. In fact, the psychiatric phenotype has not yet been extensively studied. Many data are available for facial emotion recognition and ToM, but a lack of research in social perception/knowledge and attributional style has been highlighted. Thus, it remains unclear whether individuals with a rare developmental syndrome show similar impairments in these areas. Moreover, impairments may be specific to tasks and emotions, rather than all social cognitive processes. The use of relatively consistent methodology across study designs would help compare these impairments.

Summary and Conclusion

To sum up, some social trainings, such as the use of the eye-tracking technology in RS or the focus on visuospatial functions in 22q11.2DS, are created among the specific profile of individuals with a neurodevelopmental syndrome. Understanding the differences in the social cognitive abilities of people with rare neurodevelopmental disorders may lead to a more personalized medicine. This review suggests that cognitive remediation therapy and SCT may be a viable way to improve the social and functional outcomes, although many questions on its effectiveness still need to be answered.

The studies targeting social cognition processes offer new thoughts about the development of specific cognitive training programs, as they highlight the importance of connecting neurocognitive and social cognitive training techniques. They point out that individuals with social cognitive impairments may need more help in terms of social interactions. They provide keys for caregivers, who may better adjust their communication with explicit social cues by mentioning what they are thinking or feeling and why. Understanding and adjusting attitudes to individuals with social cognition impairments are required to prevent frustration and maladaptive behaviors.

Availability of Data and Supporting Materials Section

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Author Contributions

AM elaborated the PRISMA review. AM and CD wrote the paper and collected the data. EP, AL, EF, and NF collected the data. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

22q11.2DS, 22q11.2 deletion syndrome; AAC, augmentative and alternative communication; ASD, Autism spectrum disorder; AS, Angelman syndrome; CA, chronological age; DS, Down syndrome; FXS, Fragile X syndrome; IQ, intelligence quotient; KS, Klinefelter Syndrome; MA, Mental Age; NA, non available; PWS, Prader–Willi syndrome; RS, Rett Syndrome; SMS, Smith–Magenis syndrome; TD, typically developing; TDCA, typically developing matched on chronological age; TDMA, typically developing matched on mental age; ToM, theory of mind; TS, Turner syndrome; VIQ, verbal intelligence quotient; VMA, Verbal Mental Age; WS, Williams syndrome.

References

- 1.Crespi B. Genomic imprinting in the development and evolution of psychotic spectrum conditions. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc (2008) 83(4):441–93. 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2008.00050.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crespi B, Badcock C. Psychosis and autism as diametrical disorders of the social brain. Behav Brain Sci (2008) 31(3):241–60. 10.1017/S0140525X08004214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crespi B, Summers K, Dorus S. Genomic sister-disorders of neurodevelopment: an evolutionary approach. Evol Appl (2009) 2(1):81–100. 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2008.00056.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norkett EM, Lincoln SH, Gonzalez-Heydrich J, D’Angelo EJ. Social cognitive impairment in 22q11 deletion syndrome: A review. Psychiatry Res (2017) 253:99–106. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biswas AB, Furnis F. Cognitive phenotype and psychiatric disorder in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: A review. Res Dev Disabil (2016) 53(54):242–57. 10.1016/j.ridd.2016.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swillen A. The importance of understanding cognitive trajectories: the case of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Curr Opin Psychiatry (2016) 29(2):133–7. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bostrom C, Yau SY, Majaess N, Vetrici M, Gil-Mohapel J, Christie BR. Hippocampal dysfunction and cognitive impairment in Fragile-X Syndrome. Neurosci Biobehav Rev (2016) 68:563–74. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.06.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whittington J, Holland T. Recognition of emotion in facial expression by people with Parder-Willi syndrome. J Intellect Disabil Res (2011) 55(1):75–84. 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01348.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rice LJ, Einfeld SL. Cognitive and behavioural aspects of Prader-Willi syndrome. Curr Opin Psychiatry (2015) 28(2):102–6. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poisson A, Nicolas A, Cochat P, Sanlaville D, Rigard C, de Leersnyder H, et al. Behavioral disturbance and treatment strategies in Smith-Magenis syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis (2015) 4(10):111. 10.1186/s13023-015-0330-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher MH, Morin L. Addressing social skills deficits in adults with Williams syndrome. Res Dev Disabil (2017) 71:77–87. 10.1016/j.ridd.2017.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green MF, Olivier B, Crawley JN, Penn DL, Silverstein S. Social cognition in schizophrenia: recommendations from the measurement and treatment research to improve cognition in schizophrenia. New approaches conference. Schizophr Bull (2005) 31(4):882–7. 10.1093/schbul/sbi049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elfenbein HA, Ambady N. On the universality and cultural specificity of emotion recognition: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull (2002) 128(2):203–35. 10.1037/0033-2909.128.2.203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ekman P. Universal and Cultural Differences in Facial Expression of Emotion. Lincoln, NB: Nebraska University Press; (1972). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calder AJ, Young AW, Perrett DI, Etcoff NL, Rowland D. Categorical perception of morphed facial expressions. Vis cogn (1996) 3(2):81–117. 10.1080/713756735 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baron-Cohen S. Mindblindness: An Essay on Autism and Theory of Mind. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Premack D, Woodruff G. Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? Behav Brain Sci (1978) 1(4):515–26. 10.1017/S0140525X00076512 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wimmer H, Perner J. Beliefs about beliefs: representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children’s understanding of deception. Cognition (1983) 13(1):103–28. 10.1016/0010-0277(83)90004-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalbe E, Schlegel M, Sack AT, Nowak DA, Dafotakis M, Bangard C, et al. Dissociating cognitive from affective theory of mind: a TMS study. Cortex (2010) 46(6):769–80. 10.1016/j.cortex.2009.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shamay-Tsoory SG, Aharon-Peretz J. Dissociable prefrontal networks for cognitive and affective theory of mind: a lesion study. Neuropsychologia (2007) 45(13):3054–67. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fiske ST, Taylor SE. Social Cognition. 2nd ed New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co; (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oskarsdottir S, Vujic M, Fasth A. Incidence and prevalence of the 22q11 deletion syndrome: a population-based study in Western Sweden. Arch Dis Child (2004) 89(2):148–51. 10.1136/adc.2003.026880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shprintzen RJ. Velo-cardio-facial syndrome: 30 years of study. Dev Disabil Res Rev (2008) 14(1):3–10. 10.1002/ddrr.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Angkustsiri K, Goodlin-Jones B, Deprey L, Brahmbhatt K, Harris S, Simon TJ. Social impairments in chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11.2DS): autism spectrum disorder or a different endophenotype? J Autism Dev Disord (2014) 44(4):739–46. 10.1007/s10803-013-1920-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jalbrzikowski M, Carter C, Senturk D, Chow C, Hopkins JM, Green MF, et al. Social cognition in 22q11.2 microdeletion syndrome: relevance to psychosis. Schizophr Res (2012) 142(1–3):99–107. 10.1016/j.schres.2012.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Debbané M, Glaser B, David MK, Feinstein C, Eliez S. Psychotic symptoms in children and adolescents with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: neuropsychological and behavioral implications. Schizophr Res (2006) 84(2–3):187–93. 10.1016/j.schres.2006.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buckley RH, Dinno N, Weber P. Angelman syndrome: are the estimates too low? Am J Med Genet (1998) 80(4):385–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petersen MB, Brondum-Nielsen K, Hansen LK, Wulff K. Clinical, cytogenetic, and molecular diagnosis of Angelman syndrome: estimated prevalence rate in a Danish county. Am J Med Genet (1995) 60(3):261–2. 10.1002/ajmg.1320600317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mount R, Oliver C, Berg K, Horsler K. Effects of adult familiarity on social approach behaviours in Angelman syndrome. J Intellect Disabil Res (2011) 55:339–50. 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01364.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adams D, Horsler K, Oliver C. Age related change in social behaviour in children with Angelman syndrome. Am J Med Genet A (2011) 155:1290–7. 10.1002/ajmg.a.33964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walz NC. Parent report of stereotyped behaviors, social interaction, and developmental disturbances in individuals with Angelman syndrome. J Autism Dev Disord (2007) 37:940–7. 10.1007/s10803-006-0233-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steffenburg S, Gillberg CL, Steffenburg U, Kyllerman M. Autism in Angelman syndrome: a population-based study. Pediatr Neurol (1996) 14:131–6. 10.1016/0887-8994(96)00011-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crawford DC, Acuña JM, Sherman SL. FMR1 and the Fragile X syndrome: human genome epidemiology review. Genet Med (2001) 3(5):359–71. 10.1097/00125817-200109000-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hall SS, Frank MC, Pusiol GT, Farzin F, Lightbody AA, Reiss AL. Quantifying Naturalistic social gaze in Fragile X syndrome using a novel eye tracking paradigm. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet (2015) 168(7):564–72. 10.1002/ajmg.b.32331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murphy MM, Abbeduto L, Schroeder S, Serlin R. Contribution of social and information-processing factors to eye-gaze avoidance in Fragile X syndrome. Am J Ment Retard (2007) 112:349–60. 10.1352/0895-8017(2007)112[0349:COSAIF]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baumgardner TL, Reiss AL, Freund LS, Abrams MT. Specification of the neurobehavioral phenotype in males with Fragile X syndrome. Paediatrics (1995) 5:744–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turk J, Cornish K. Face recognition and emotional perception in boys with Fragile X syndrome. J Intellect Disabil Res (1998) 42(6):490–9. 10.1046/j.1365-2788.1998.4260490.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bojesen A, Juul S, Gravholt C. Prenatal and postnatal prevalence of Klinefelter syndrome: a national registry study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2003) 88(2):622–6. 10.1210/jc.2002-021491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bishop DV, Jacobs PA, Lachlan K, Wellesley D, Barnicoat A, Boyd PA, et al. Autism, language and communication in children with sex chromosome trisomies. Arch Dis Child (2011) 96:954–9. 10.1136/adc.2009.179747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cordeiro L, Tartaglia N, Roeltgen D, Ross J. Social deficits in male children and adolescents with sex chromosome aneuploidy: a comparison of XXY, XYY, and XXYY syndromes. Res Dev Disabil (2012) 33:1254–63. 10.1016/j.ridd.2012.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whittington J, Holland A, Webb T, Butler J, Clarke D, Boer H. Population prevalence and estimated birth incidence and mortality rate for people with Prader-Willi syndrome in one UK health region. J Med Genet (2001) 38(11):792–8. 10.1136/jmg.38.11.792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kerr AM, Witt Engerström I. The clinical background to the Rett disorder. In: Ingegerd WE, Kerr AM, editors. Rett Disorder and the Developing Brain. Oxford: Oxford University Press; (2001). p. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bartl-Pokorny KD, Marschik PB, Sigafoos J, Tager-Flusberg H, Kaufmann WE, Grossmann T, et al. Early socio-communicative forms and functions in typical Rett syndrome. Res Dev Disabil (2013) 34:3133–8. 10.1016/j.ridd.2013.06.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Didden R, Korzilius H, Smeets E, Green VA, Lang R, Lancioni GE, et al. Communication in individuals with Rett syndrome: an assessment of forms and functions. J Dev Phys Disabil (2010) 22:105–18. 10.1007/s10882-009-9168-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Urbanowicz A, Leonard H, Girdler S, Ciccone N, Downs J. Parental perspectives on the communication abilities of their daughters with Rett syndrome. Dev Neurorehabil (2016) 19:17–25. 10.3109/17518423.2013.879940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Juyal RC, Figuera LE, Hauge X, Elsea SH, Lupski JR, Greenberg F, et al. Molecular analyses of 17p11.2 deletions in 62 Smith-Magenis syndrome patients. Am J Hum Genet (1996) 58(5):998–1007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martin SC, Wolters PL, Smith ACM. Adaptive and maladaptive behavior in children with Smith-Magenis syndrome. J Autism Dev Disord (2006) 36:541–52. 10.1007/s10803-006-0093-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sarimski K. Communicative competence and behavioral phenotype in children with Smith–Magenis syndrome. Genet Couns (2004) 15:347–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stochholm K, Juul S, Juel K, Naeraa RW, Gravholt CH. Prevalence, incidence, diagnostic delay, and mortality in Turner syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2006) 91(10):3897–902. 10.1210/jc.2006-0558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lagrou K, Froidecoeur C, Verlinde F, Craen M, De Schepper J, François I, et al. Psychosocial functioning, selfperception and body image and their auxologic correlates in growth hormone and oestrogen-treated young adult women with Turner syndrome. Horm Res (2006) 66:277–84. 10.1159/000095547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McCauley E, Feuillan P, Kushner H, Ross JL. Psychosocial development in adolescents with Turner syndrome. J Dev Behav Pediatr (2001) 22:360–5. 10.1097/00004703-200112000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hong DS, Dunkin B, Reiss AL. Psychosocial functioning and social cognitive processing in girls with Turner syndrome. J Dev Behav Pediatr (2011) 32:512–20. 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3182255301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lepage JF, Dunkin B, Hong DS, Reiss AL. Impact of cognitive profile on social functioning in prepubescent females with Turner syndrome. Child Neuropsychol (2013) 19:161–72. 10.1080/09297049.2011.647900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suzigan LZ, de Paiva e Silva RB, Guerra-Júnior G, Marini SH, Maciel-Guerra AT. Social skills in women with Turner syndrome. Scand J Psychol (2011) 52:440–7. 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2011.00887.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Strømme P, Bjornstad PG, Ramstad K. Prevalence estimation of Williams syndrome. J Child Neurol (2002) 17(4):269–71. 10.1177/088307380201700406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Klein-Tasman BP, Mervis CB, Lord C, Phillip K. Socio-communicative deficits in young children with Williams syndrome: performance on the autism diagnostic observation schedule. Child Neuropsychol (2007) 13:444–67. 10.1080/09297040601033680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hanley M, Riby DM, Caswell S, Rooney S, Back E. Looking and thinking: how individuals with Williams syndrome make judgments about mental states. Res Dev Disabil (2013) 34(12):4466–76. 10.1016/j.ridd.2013.09.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Porter MA, Coltheart M. Cognitive heterogeneity in Williams syndrome. Dev Neuropsychol (2005) 27:275–306. 10.1207/s15326942dn2702_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Campbell L, McCabe K, Leadbeater K, Schall U, Loughland C, Rich D. Visual scanning of faces in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: attention to the mouth or the eyes? Psychiatry Res (2010) 177(1–2):211–5. 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Campbell LE, Stevens AF, McCabe K, Cruickshank L, Morris RG, Murphy DGM, et al. Is theory of mind related to social dysfunction and emotional problems in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (velo-cardio-facial syndrome)? J Neurodev Disord (2011) 3(2):152–61. 10.1007/s11689-011-9082-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]