Abstract

Background

The majority of breast cancer cases are steroid dependent neoplasms, with hormonal manipulation of either CYP19/aromatase or oestrogen receptor alpha axis being the most common therapy. Alternate pathways of steroid actions are documented, but their interconnections and correlations to BC subtypes and clinical outcome could be further explored.

Methods

We evaluated selected steroid receptors (Androgen Receptor, Oestrogen Receptor alpha and Beta, Glucocorticoid Receptor) and oestrogen pathways (steroid sulfatase (STS), 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 2 (17βHSD2) and aromatase) in a cohort of 139 BC cases from Norway. Using logistic and cox regression analysis, we examined interactions between these and clinical outcomes such as distant metastasis, local relapse and survival.

Results

Our principal finding is an impact of STS expression on the risk for distant metastasis (p<0.001) and local relapses (p <0.001), HER2 subtype (p<0.015), and survival (p<0.001). The suggestion of a beneficial effect of alternative oestrogen synthesis pathways was strengthened by inverted, but non-significant findings for 17βHSD2.

Conclusions

Increased intratumoural metabolism of oestrogens through STS is associated with significantly lower incidence of relapse and/or distant metastasis and correspondingly improved prognosis. The enrichment of STS in the HER2 overexpressing subtype is intriguing, especially given the possible role of HER-2 over-expression in endocrine resistance.

Subject terms: Breast cancer, Endocrine cancer

Introduction

Primary breast cancer survival rates have improved dramatically over the last three decades, both in relationship to itself and relative to other cancers.1 This improvement has been achieved, at least partially, through the increased effectiveness of targeted endocrine therapies such as aromatase inhibition2 and modulation of oestrogen receptor signalling, as well as the development of monoclonal antibodies targeting the HER2/neu receptor.3 Despite these manifest improvements in prognosis there are still some areas in breast cancer treatment that remain challenging. These include the identification of more aggressive vs indolent cancers, the treatment of inherently difficult subtypes such as triple negative breast cancer (TNBC; ERα, PR negative, HER2 not overexpressed), de novo and acquired resistance to therapy causing therapeutic failure during adjuvant therapy and, finally, treatment of metastatic disease.

Breast cancer has in general a well-documented dependence on classically female sex steroids, oestrogens, and progesterone. The importance of these hormones in the etiology and maintenance of breast cancer is illustrated in the effectiveness of the therapeutic approaches based on oestrogen depletion or blockade. However, in an attempt to meet the challenges above, the study of the wider range of steroidogenic pathways in the breast is becoming a core component. This wider range of targets encompasses a broader view of pathways that may modulate oestrogen action as well as other classes of steroid molecules such as androgens and glucocorticoids. The overall goal is to explore the cross-talk between the involved steroidal pathways to better understand and overcome, or at least further delay, resistance to endocrine therapy.

Steroid metabolising enzymes other than aromatase have long been considered potential candidates for breast cancer therapy and important components in the modulation of localised oestrogen levels4–8 (Fig. 1). In particular, expression of the STS, 17βHSD1, and 17βHSD2 enzymes have been considered central and important players. 17βHSD1 and 2 have opposite actions modulating the 17 C functional group between a hydroxyl (–OH) and ketone (=O) formation, and thus controlling the relative levels of, e.g., estradiol and estrone.9,10 17βHSD1 catalyses the less potent estrone to the more potent estradiol while 17βHSD2 performs the reverse function. Steroid sulfatase (STS) functions to convert sulfated steroids to their non-sulfated forms (“free steroids”).9 This is important as many steroids circulate in their sulfated form in vast excess compared to the non-conjugated forms and thus the presence of STS indicates the ability of the tumour cell to potentially tap a greatly increased reserve of steroids. Previous studies investigating the impact of these enzymes on breast cancers have found that they are influencing BC prognosis, most probably through an alternate oestrogen supply to the breast tissue.7,11–13 On the basis of this and other potential therapeutic applications a variety of STS inhibitors have been developed in the last three decades and investigated in preclinical models as potential therapeutic agents in breast cancer,14,15 comprehensively reviewed in refs.16,17 Results from initial and subsequent clinical trials examining the efficiency of a first generation STS inhibition (STX64/Irosustat) in advanced breast cancer show promising results.18,19

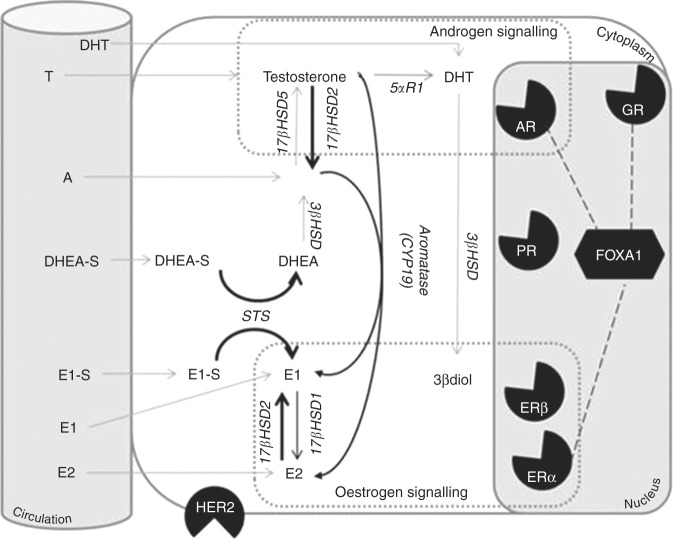

Fig. 1.

Overview of the steroidogenic pathways thought to be functional in the breast. The classical steroid receptors thought to govern breast cancer prognosis are the oestrogen receptor alpha (ERα) and the Progesterone Receptor (PR). In addition to these the Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2)is also part of the classical panel used to asses breast cancers. This figure demonstrate the extended endocrine environment of the breast with pathways considered in this paper in black, and additional important and potential pathways not studied in grey. This figure is not intended to be a comprehensive diagram of all possible intracrine pathways present in the breast but a guide to the reader of this paper to help orientate them to the significance of the various proteins examined. Circulating precursors such as DHEA-S and E1-S are found in high concentrations in the circulation as are smaller levels of more active steroids such as oestrone (E1), estradiol (E2), Androstenedione (A) and testosterone and cortisol (not shown). Through a series of enzymatic conversions these steroids can be modulated to have greater or lesser activity on a variety of nuclear receptors such as the androgen receptor (AR), oestrogen receptor beta (ERβ) and glucocorticoid receptor (GR) in addition to the classical hormone receptors. Beyond the actions of nuclear receptors the role of cofactors such as FOXA1 and their interactions with hormone receptors are thought to be central to understanding this complex network of interactions

In addition, androgens have been a resurgent area of breast cancer research over the last decade. Androgens were originally proposed as agonists in the treatment of breast cancer,20,21 however, their use was discontinued due to the efficacy and tolerability of tamoxifen. In the modern era of research into androgen actions in breast cancers, a great deal of focus has recently been placed on their actions in the triple negative subtype,22 partially through the appeal of androgen modulation as an effective and available therapeutic treatment for these difficult to treat cancers.23 Beyond this the potential of androgen modulation even in ER positive subtypes is once again being considered.24,25

Glucocorticoid effects in primary tumours have been a poorly investigated area of breast cancer biology. In the limited studies available, most suggest that the presence of the glucocorticoid receptor in tissue predicts a worse prognosis (Reviewed in refs.26,27). However, there is some suggestion that this may be dependent on ER status with worse prognosis observed in ER negative disease but better prognosis observed in ER positive disease.28 Overall, the effect of glucocorticoids is thought to be inhibition of both proliferation and apoptosis, the latter being the most concerning in the context of cancer chemotherapy.

Finally, often these pathways are studied in isolation yet they are inherently connected at multiple levels. Androgens serve as an obligate precursor for the local production of oestrogens, the androgen and glucocorticoid receptors are well known to share a DNA binding motif with the FOXA1 transcription factor (Fig. 1) playing an interplay role between these pathways.29–31 In this study we sought to analyse the impact of these factors individually but also and importantly in combination across breast cancer tumour subtypes and in relation to clinicopathological factors and outcomes.

Materials and methods

Patient cohort

All patients were recruited at the department of breast and endocrine surgery at the Akershus University Hospital, Lørenskog, Norway. Patients gave their written informed consent prior to sampling. The experiments were approved by the Regional Ethics Committee of South-East Norway (Project number: 2014–895). Patients' characteristics are summarised in Table 1. ER, PR, and HER2 status was drawn from the clinical records of patients and was evaluated as follows. Histological samples were fixed in Neutral buffered formalin and paraffin embedded (Table 2). For immunohistochemistry 3 micron thick sections were cut and subsequently stained with the Ventana Benchmark Ultra immunostainer (Ventana Medical Systems, Roche) with iView DAB Detection Kit (Roche) and ultraView Universal Alkaline Phosphatase Red Detection Kit (Roche). The following are the antibodies and criteria used for positivity in determining the ER/PR and HER2 status of the tumour; ER: CONFIRM anti-Oestrogen Receptor (ER) (SP1) Rabbit Monoclonal Primary Antibody (Roche) Positive nuclear staining in >1% of tumour cell nuclei registered as positive irrespective of staining intensity; PR: CONFIRM anti-Progesterone Receptor (PR) (1E2) Rabbit Monoclonal Primary Antibody (Roche).

Table 1.

Clinicopathological charateristics

| Variable | Value (N) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole cohort | Post-menopausal | Pre-menopausal | |

| Age | |||

| Mean | 60.5 | 66.4 | 41.1 |

| Highest | 92 | 92 | 51 |

| Lowest | 34 | 49 | 34 |

| Grade | |||

| 1 | 8 (5.9%) | 4 (4.3%) | 2 (12.5%) |

| 2 | 69 (50.8%) | 50 (53.7%) | 4 (25.0%) |

| 3 | 59 (43.3%) | 39 (41.9%) | 10 (62.5%) |

| Tumour size (T) | |||

| 1 (<2 cm) | 63 (45.3%) | 47 (48.9%) | 4 (25.0%) |

| 2 (2–5 cm) | 70 (50.4%) | 47 (48.9%) | 10 (62.5%) |

| 3 (>5 cm) | 6 (4.3%) | 2 (2.1%) | 2 (12.5%) |

| Nodal spread (N) | |||

| 0 (no spread to lymph) | 77 (55.8%) | 54 (56.8%) | 9 (56.2%) |

| 1 (1–3 pos. lymph nodes) | 36 (26.1%) | 26 (27.3%) | 3 (18.75%) |

| 2 (4–9 pos. lymph nodes) | 14 (10.1%) | 11 (11.5%) | 1 (6.2%) |

| 3 (>10 pos. lymph nodes) | 11 (8.0%) | 4 (4.2%) | 3 (18.75) |

| Metastasis (M) | |||

| No Met | 137 (96.6%) | 93 (97.8%) | 16 (100%) |

| Mets | 2 (1.4%) | 2 (2.2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Menopausal status | |||

| Pre-menopausal | 16 (11.5%) | ||

| Post-menopausal | 96 (69.1%) | ||

| Unknown | 27 (19.4%) | Excluded | |

| BC subtype | |||

| HER2 | 37 (26.6%) | 26 (27.2%) | 6 (37.5%) |

| LUMA | 74 (53.2%) | 49 (51.0%) | 7 (43.7%) |

| LUMB | 11 (7.9%) | 8 (8.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| TNBC | 17 (12.2%) | 13 (13.5%) | 3 (18.75%) |

| Relapse (local and metastatic) | |||

| No | 94 (67.7%) | 64 (68.1%) | 11 (68.7%) |

| Yes | 45 (32.3%) | 30 (31.9%) | 5 (31.2%) |

| Relapse (metastatic) | |||

| No | 96 (69.1%) | 62 (66.7%) | 11 (68.7%) |

| Yes | 43 (30.9%) | 31 (33.3%) | 5 (31.2%) |

| Oestrogen receptor α | |||

| Negative | 36 (25.9%) | 26 (27.1%) | 5 (31.2%) |

| Positive | 103 (74.1%) | 70 (71.9%) | 11 (68.7%) |

| PGR | |||

| Negative | 74 (53.2%) | 53 (55.2%) | 7 (42.7%) |

| Positive | 65 (46.8%) | 43 (44.8%) | 9 (56.3%) |

| HER2 over-expression | |||

| No | 99 (71.2%) | 67 (69.8%) | 10 (62.5%) |

| Yes | 40 (28.8%) | 29 (30.2%) | 6 (37.5%) |

| STERSULF | |||

| Negative | 57 (41.3%) | 42 (44.2%) | 6 (37.5%) |

| Positive | 81 (58.7%) | 53 (55.8%) | 10 (62.5%) |

| Aromatase | |||

| Score 1–4 | 40 (28.2%) | 27 (38.6%) | 3 (30%) |

| Score 5–7 | 90 (71.2%) | 43 (61.4%) | 7 (70%) |

| 17βHSD Type 2 | |||

| Negative | 25 (18.1%) | 21 (22.1%) | 2 (12.5%) |

| Positive | 113 (81.9%) | 74 (77.9%) | 14 (87.5%) |

| ERβ1 | |||

| <150 H Score | 65 (46.7%) | 47 (49.0%) | 7 (43.7%) |

| >150 H score | 74 (53.2%) | 49 (51.0%) | 9 (56.3%) |

| AR | |||

| <10% | 18 (13.3%) | 12 (13.0%) | 1 (6.25%) |

| ≥10% | 117 (86.7%) | 80 (87.0%) | 15 (93.75%) |

| GR | |||

| <10% | 64 (48.5%) | 41 (45.1%) | 11 (73.3%) |

| ≥10% | 68 (51.5%) | 50 (54.1%) | 4 (26.6%) |

| FOXA1 | |||

| <10% | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| ≥10% | 132 (100% | 90 (100%) | 16 (100%) |

| KI67 | |||

| <15 | 31 (22.6%) | 21 (22.3%) | 2 (12.5%) |

| 15–30 | 37 (27.0%) | 26 (27.7%) | 2 (12.5%) |

| >30 | 69 (50.4%) | 47 (50%) | 12 (75.0%) |

Clinicopathological and histological characteristics of the cohort

Table 2.

Breast cancer subtype and marker expression

| Luminal A | Luminal B | HER2 | TNBC | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oestrogen receptor α | |||||

| Positive | 74 | 11 | 18 | 0 | — |

| Negative | 0 | 0 | 19 | 17 | |

| Progesterone receptor | |||||

| Positive | 49 | 6 | 10 | 0 | — |

| Negative | 25 | 5 | 27 | 17 | |

| STS | |||||

| Positive | 39 | 4 | 28 | 10 | 0.0274 |

| Negative | 35 | 7 | 8 | 7 | |

| 17βHSD2 | |||||

| Positive | 60 | 9 | 30 | 14 | 0.9934 |

| Negative | 14 | 2 | 6 | 3 | |

| Aromatase | |||||

| Score 1–4 | 20 | 3 | 10 | 7 | 0.69 |

| Score 5–7 | 54 | 8 | 27 | 10 | |

| Oestrogen receptor β1 | |||||

| Average±SD | 183.8 ± 76.8 | 147 ± 74.6 | 164 ± 80.9 | 126.3 ± 85.9 | 0.041 |

| Range | 21.3–300.5 | 75.6–264 | 8.5–313 | 14–264 | |

| Androgen receptor | |||||

| Positive | 62 | 10 | 35 | 10 | 0.0119 |

| Negative | 8 | 1 | 2 | 7 | |

| Glucocorticoid receptor | |||||

| Positive | 40 | 4 | 15 | 9 | 0.2898 |

| Negative | 30 | 7 | 21 | 6 | |

| Ki67 | |||||

| <15% | 25 | 1 | 4 | 1 | <0.001 |

| 15–30% | 24 | 5 | 5 | 3 | |

| >30% | 24 | 5 | 17 | 13 |

Correlation of nuclear receptors and steroidogenic enzymes with breast cancer subtype

Positive nuclear staining in >10% of tumour cell nuclei registered as positive irrespective of staining intensity. HER-2 antibody: PATHWAY anti-HER-2/neu (4B5) Rabbit Monoclonal Primary Antibody (Roche) Membrane staining evaluated as follows: no staining (=0), weak to moderate incomplete staining (=1+), moderate complete membrane staining in >10% of tumour cells (=2+) and marked/intense membrane staining in >10% of tumour cells (=3+). 0 and 1 + registered as HER-2 negative case 2+inconclusive, assessed by dual SISH (Roche). 3+ registered as positive for HER-2. INFORM HER2 Dual ISH DNA Probe Cocktail Assay and ultraVIEW SISH Detection Kit (Roche) Dual SISH with silver stained HER-2 signals and red CEP (centromere) 17 signals. A ratio gene signal number/CEP17 signal number >2.0 registers as HER-2 gen amplified. Sufficient clinical material to perform analysis of steroidogenic enzymes was available from 139 patients. The mean age of the study population was 59 years (range: 34–93 years).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for AR, GR, CYP19 (aromatase), 17βHSD2, STS, FOXA1, and ERβ was performed, as previously described.12,32–35 In brief, the following primary antibodies and conditions were employed; (Ki67 (MIB-1) DAKO 1:100; AR (AR441)DAKO 1:50; GR, (D6H2L)Cell Signalling technologies 1:400; AROM (677), Novartis, 1:500; 17βHSD2, Proteintech, 1:200; STS, (KW1049) Kyowa medix, 1:100; FOXA1 (3C1) ABCAM 1:200, ERβ1 1:1000 (Genetex, 14C8)). Heat based antigen retrieval using 10 mM citric acid buffer (ph6.0) was performed for AR, GR, ERβ, FOXA1, Ki67, STS, aromatase and 17βHSD2. In all cases the Nichirei staining system based upon streptavidin peroxidase conjugation was used for the visualisation of primary antibody binding. The robustness and reproducibility of the method was confirmed by the inclusion of a verified positive control tissue with each IHC run.

The slides were independently evaluated by at least two authors for each stain (KMM, FG) blinded to patients clinical outcomes. Nuclear stains were quantified using the H-score. This gives a measure of intensity and prevalence along a scale of 0–300 on the basis of 5 hot spots in the tissue and the labelling index was used for Ki67. The evaluation of CYP19/aromatase was performed by assessing the approximate percentage of cells staining (proportion score) and classifying the level into four groups: 0 = <1%, 1 = 1–25%, 2 = 26–50%, and 3 = >50% immuno-positive cells, and the relative intensity of immune-positive cells was classified as follows: 0 = no immune-reactivity, 1 = weak, 2 = moderate and 3 = strong immune-reactivity. The total score was the addition of the proportion score and the relative immune-intensity score.36 The staining of the other enzymes was assessed across the whole carcinoma section and categorised into one of three groups: no staining (0), <50% staining (1), >50% staining (2)12,33–35

Statistical analysis

Raw data were examined for distribution. Since most of the variables to be considered are categorical, the relationships between them are presented using cross-tables with raw numbers. The STS and 17βHSD2 variables are scored in 3 categories (Negative, 1–50%, greater than 50%) but for the purpose of analysis were transformed into a dichotomous variable, with “negative” coded as negative, and positive otherwise. Ki-67 is a continuous variable and was treated as such in the statistical analyses, but for tabulation purposes it is divided into three ranges: smaller than 15%, 15–30%, and greater than 30%.

Univariate logistic regression modeling was used for statistical inference of the relationship between relapse and metastasis and the enzymes and nuclear receptors. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and logistic regression was used to test association between endocrine therapy and BC subtype against enzymes and nuclear receptors.

The effect of our endocrine markers on survival from the time of surgery was analysed using Cox regression including the age of the patient as a covariate. The survival time was visualised using Kaplan–Meier curves.

As many tests were performed, it is worthwhile to keep in mind the potential effects of multiple hypothesis testing. As such in the text we have given the actual P value rather than using a cut-off point of p > 0.05. As a rule of thumb we used the more stringent p < 0.005 for considering an association to be statistically significant.

All analyses were done in R version 3.2.0.37

Results

Localisation, distribution and correlations of steroidogenic markers

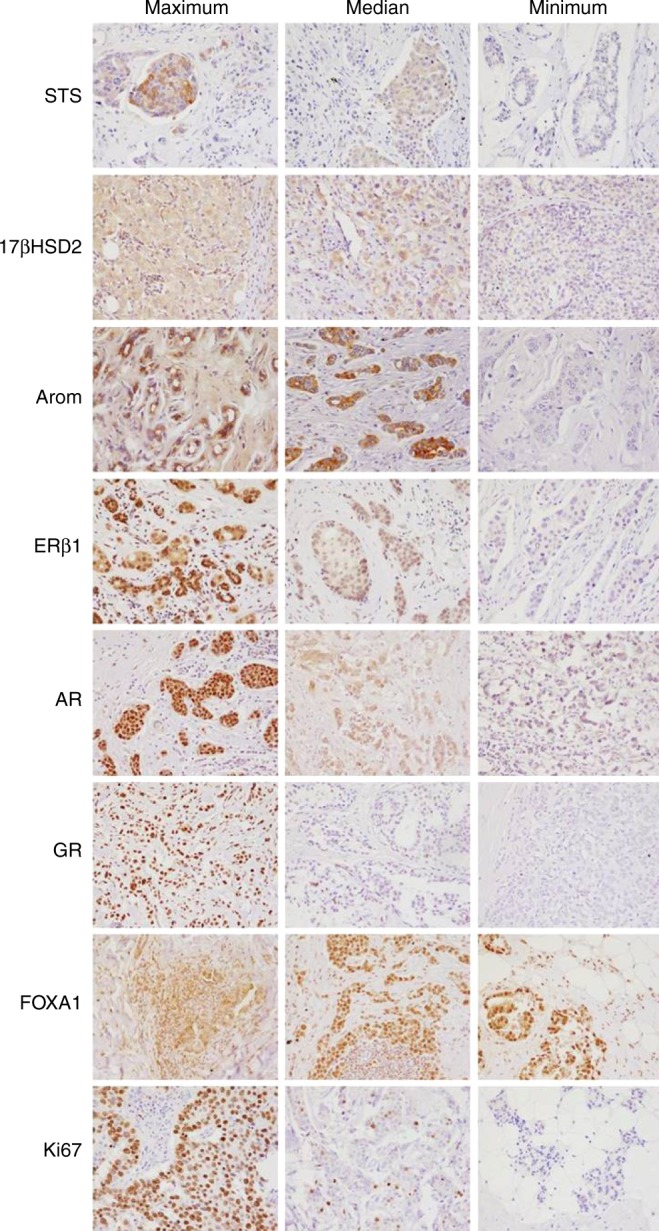

Patient cohort characteristics alongside IHC marker expression are summarised in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. As can be seen in the representative images shown in Fig. 2 the most marked immunoreactivity of all markers studied was in the carcinoma cells. AR and GR were observed in a predominantly nuclear localisation while aromatase, STS and 17βHSD2 were mostly cytoplasmic. The proportion of patients that were positive for any stain varied. Correlations between these various markers were observable but relatively weak (below r = 0.03, Supplementary Data 1). AR was strongly correlated with GR, FOXA1, ERβ and aromatase; ERβ was strongly correlated with AR, Aromatase and FOXA1; and GR was correlated with STS. FOXA1 was inversely correlated with Ki67 with a similar trend observable for ERβ1. When using a Bonferroni correction to control for multiple comparisons, the only effect that remained below p < 0.005 was the association between ERβ1 and aromatase score (p = 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Representative IHC images of immunohistochemical stains in breast cancer samples. For each stain we chose the maximal, median and minimal values of the stain and have shown the representative images (×200 magnification). Note in most cases the epithelial location of the staining. While not illustrated here is should be noted that over and entire section of cancer tissue some of these stains were heterogeneous thus the possibility of steroid expressing subpopulations within the one tumour should not be ruled out. At present however there are few scoring approaches to adequately asses this issue and as such it is not dealt with in this manuscript

For the nuclear receptors and transcription factor it was necessary for some analysis to create dichotomised values (positive/negative). This was based on a cut-off of 10% labelling index. 74% of cases were positive for ERβ, 86% of cases were considered positive for AR and 51% positive for GR. An additional marker, the important nuclear transcription factor FOXA1 was also included in the analysis. However, 100% of the samples demonstrated immunoreactivity in this cohort and thus it was not possible to dichotomise the cohort into positive and negative values. For the enzymes, dichotomised as described in methods above, a majority of cases were positive to some degree for aromatase, STS and 17βHSD2 (Table 1).

Relationship between clinicopathological factors, breast cancer subtype and marker expression

In evaluating relationships between clinicopathological characteristics and breast cancer subtypes we found that there was an association between subtype and proliferation with Ki67 levels being lower in the luminal A subtype compared to HER2-positive (p < 0.001) and TNBC (p < 0.001), as expected. Moreover, luminal A cancers had the highest rates of PR positivity and were statistically more likely to be PR positive compared to HER2 subtype (p < 0.001), as expected (Table 2). Interestingly menopausal status seemed to not strongly affect marker expression (Supplementary Table 1) with GR being the only protein suggestive of being linked to menopausal status (p = 0.051, Odds ratio 3.35, increased in post-menopausal patients)

When examining the relationship between the steroidogenic proteins and breast cancer subtypes via regression analysis, only three patterns were apparent. First, AR expression (H Score) score varied between the TNBC subtype and others (p = 0.01) with significantly lower levels in TNBC compared to the Luminal A (p = 0.0025) and HER2 subgroupings (p = 0.0341). Second, STS expression (dichotomised value) also varied between the subtypes (p = 0.027) with lower rates in the luminal groupings compared to the HER2 subgrouping (p < 0.015). Finally, ERβ expression (H Score) was associated with significant differences across subtypes (p = 0.041) with highest levels in the luminal A subgrouping and the lowest levels in the TNBC grouping and differences in ERβ expression between the luminal A and TNBC groupings (p = 0.0077).

Relationship between markers and recurrence

The relationships between the markers we examined and local recurrence and distal metastasis are given in Tables 3. The marker most strongly associated with recurrence or distal metastasis was STS. Positive STS expression in a tumour correlated with a significantly lower rate of local recurrence or distal metastasis (OR = 0.25, p < 0.001; OR = 0.17, p < 0.001). 17βHSD2 exhibited a weaker effect in the opposite direction, with positive expression associating with increased rates of local or distal recurrence (OR = 4.17, p = 0.03; OR = 3.47, p = 0.055). Descriptive statistics regarding the expression of markers in the primary tumour and eventual metastatic site(s) of recurrence are given in Supplementary table 1. Unfortunately, the comparably small numbers for each individual metastatic site precluded us from doing extensive statistical analysis on the correlation between expression and relapse site.

Table 3.

Regression analysis

| Relapse | No relapse | Regression coefficient | Odds ratio | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local relapse | |||||

| Oestrogen receptor α | |||||

| Positive | 34 | 69 | 0.1132 | 1.12 | 0.787 |

| Negative | 11 | 25 | |||

| Progesterone receptor | |||||

| Positive | 20 | 45 | −0.138 | 0.87 | 0.705 |

| Negative | 25 | 49 | |||

| HER2 | |||||

| Positive | 13 | 27 | 0.008 | 1.008 | 0.984 |

| Negative | 32 | 67 | |||

| STS | |||||

| Positive | 16 | 65 | −1.367 | 0.255 | <0.001 |

| Negative | 28 | 29 | |||

| 17βHSD2 | |||||

| Positive | 41 | 72 | 1.429 | 4.176 | 0.027 |

| Negative | 3 | 22 | |||

| Androgen receptor | |||||

| Positive | 40 | 77 | 0.955 | 2.59 | 0.149 |

| Negative | 3 | 15 | |||

| Glucocorticoid receptor | |||||

| Positive | 23 | 45 | 0.346 | 1.413 | 0.365 |

| Negative | 17 | 47 | |||

| Aromatase | |||||

| Cont. | 0.039 | 1.039 | 0.802 | ||

| Oestrogen receptor β | |||||

| Cont. | −0.002 | 0.998 | 0.304 | ||

| Ki67 | |||||

| Cont. | −0.003 | 0.99 | 0.782 | ||

| Distal relapse | |||||

| Oestrogen receptor α | |||||

| Positive | 29 | 72 | −0.034 | 0.9667 | 0.938 |

| Negative | 10 | 24 | |||

| Progesterone receptor | |||||

| Positive | 19 | 46 | 0.03209 | 1.032 | 0.932 |

| Negative | 20 | 50 | |||

| HER2 | |||||

| Positive | 13 | 25 | 0.3507 | 1.42 | 0.394 |

| Negative | 25 | 71 | |||

| STS | |||||

| Positive | 11 | 68 | −1.7852 | 0.168 | <0.001 |

| Negative | 27 | 28 | |||

| 17βHSD2 | |||||

| Positive | 35 | 74 | 1.244 | 3.468 | 0.055 |

| Negative | 3 | 22 | |||

| Androgen receptor | |||||

| Positive | 34 | 81 | 0.598 | 1.819 | 0.374 |

| Negative | 3 | 13 | |||

| Glucocorticoid receptor | |||||

| Positive | 21 | 45 | 0.5647 | 1.759 | 0.167 |

| Negative | 13 | 49 | |||

| Aromatase | |||||

| Cont. | −0.065 | 0.937 | 0.680 | ||

| Oestrogen receptor β | |||||

| Cont. | −0.001 | 0.999 | 0.662 | ||

| Ki67 | |||||

| Cont. | 0.00342 | 1.033 | 0.756 |

Relationships between nuclear receptors, steroidogenic enzymes, and clinical outcome. Samples with a P value falling below 0.05 are given in italics

Relationship between markers and survival

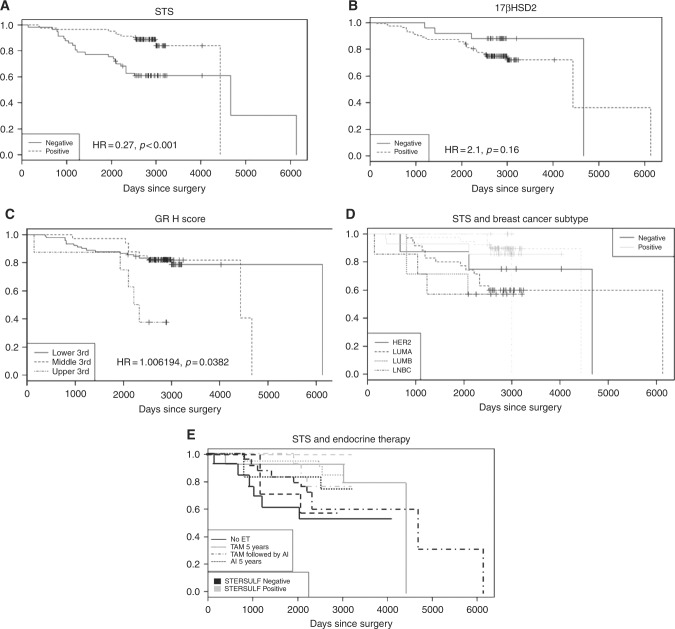

We saw no significant effects of any of our established clinico-pathological parameters (BC subtype, ER, PR, HER2, Ki67) on survival. In the steroidogenic parameters examined, only STS expression was associated with a significant survival benefit (HR = 0.27, p < 0.001). This effect was not subtype dependent. GR also impacted survival (Cox proportional hazard, adjusted for age. (HR = 1.006, p = 0.038). No other markers were associated with strong survival effects although an increased risk for relapses/metastasis was observed for elevated 17βHSD2 activity (HR = 2.1, p = 0.16).

Interactions with therapeutic treatments (endocrine and chemotherapy)

In an analysis of survival and endocrine treatment no significant differences between endocrine treatment were observed. Given that one of the main presumptive functions of STS is facilitating the supply of oestrogens to the carcinoma from otherwise unavailable circulating steroids, it is interesting to test if there is an interaction between endocrine manipulations and the survival benefit shown by STS expression. In this analysis we did not see any interactions between endocrine treatment and STS effects on survival (Fig. 3), with the outcome of each treatment being affected by STS expression. Likewise there was no correlation between aromatase expression, endocrine treatment and survival outcomes.

Fig. 3.

The impact of steroidogenic proteins on overall survival. We detected an effect of STS (a), 17βHSD2 (b), and GR (c) expression on overall survival rates with high levels of STS being associated with longer survival while high levels of 17βHSD2 and GR were associated with shorter survival. Survival analysis examining the interactions of STS expression with breast cancer subtype (d) and endocrine therapy (e) revealed that the survival benefit associated with STS expression was not confined to one breast cancer subtype or related to a specific endocrine intervention

The impact of ERα positivity within the HER2 overexpressed subtype

Given the role of STS in generating oestrogens and the possibility of an ERα positive sub-population in the HER2 overexpressing carcinomas, we tested the impact of ERα expression on STS and aromatase in this grouping. There were no differences in levels of aromatase expression dependent on ERα expression in the HER2 subtype. There was however, an inverse association between ERα expression and STS expression with ERα positive cases being less likely to express STS than ERα negative cases (p = 0.039, Regression co-efficient −1.779, Odds ratio 0.16).

Principal component analysis between variables

Using principle components analysis we examined the relationship between the variables (Supplementary Figure 1). While the data did not reveal any patterns that characterise one subtype over another, it did demonstrate the independence between the set of data.

Discussion

In this study of the interactions between clinicopathological factors and the extended intracrine tumour environment in a Norwegian breast cancer cohort, our principle finding was a strong protective effect of STS expression on local and distal recurrence as well as improved overall survival. In combination with the inverse trends seen for 17βHSD2 for the same factors, our data seems to suggest that localised synthesis of potent oestrogens by alternative steroid pathways may be protective in breast cancer and/or that depletion of oestrogens via increased metabolism of oestrone may create adverse conditions for cancer cells. A second interaction observed was the strong correlation of HER2 overexpressing carcinomas and STS expression, although HER2 expression appeared to be associated with increased rates of local and distal relapse. One note of caution should be raised in the interpretation of these findings; while we examined the protein expression of STS in the tissues we have not evidence regarding its correlation of STS activity. We are unable to validate if this increased expression indicated increased activity of STS due to the nature of the experimental samples we are working with and such experiments would be an essential future step in unravelling the correlations we have seen in this study. The same cautionary note applies to the subsequent discussion regarding the significance of nuclear receptor expression in the tissues without any information regarding nuclear receptor activity.

Our finding regarding levels of STS expression in breast carcinomas confirms previous reports,8,12 while its association with HER2 has also been previously suggested.7,38 However, our findings regarding the effects of STS on survival are contradictory to previous reports in the literature, including those from our own laboratory. Previous finding have suggested that STS is increased in malignancy,7 and expressed and functional at high levels in invasive cancers.7,8,11–13,39 Virtually all previous studies have found that STS expression is associated with worse outcomes and increased recurrence7,11–13 albeit with a few dissenting findings.39

In reconciling this data with our finding in the present study, we offer a couple of points of note. Firstly, previous studies that rely on mRNA as a surrogate of protein expression7,11,13 may not truly reflect the levels of protein or enzymatic activity of STS.40 Secondly, the previous studies have focused on specific subtypes of carcinomas, (e.g., luminal A8 while the current study investigated a wider range of carcinomas, including the HER2 overexpressing type and TNBC. A final explanation may be that previous studies have predominantly been done in cohorts where the principle ethnicity is Japanese. While it seems unlikely that such drastic differences could exist, effects of ethnicity may not be completely ruled out. These explanations do not reconcile all the difference in the data and await further study in larger cohorts at the protein and ideally enzymatic level.

In meditating on the potential significance of the protective effect of STS on outcomes there are a number of possible explanations to consider. It is interesting to speculate that after the reduction in tumour burden following surgical excision, the presence of local oestrogens may help to maintain residual cells in a luminal-like differentiated state.41 This maintenance of differentiation may thus prevent tumour cell senescence and, through the regulation of proliferation, make them more vulnerable to chemotherapy while simultaneously, through actions in EMT, make them less likely to become locally or distally invasive. Established relationships between HER2 actions and stemness make this a fascinating possibility.42 Previous research has suggested that ERβ may be present in the HER2 subtype43 and that ERβ expression is associated with STS.38 While there is not complete consensus on the role or nature of ERβ actions in breast carcinomas (reviewed in5 which may be partially due to issues with antibody choice and validation44,45 many studies as well as a recent meta-analysis, do suggest it has protective roles.46 Thus, local provision of oestrogens or androgens through the DHEA-DHT-3βdiol pathway,47 by STS could be protective in this manner. An alternate potential explanation is that the protective actions of STS may not occur exclusively through its actions on oestrogens but through actions on other steroid classes such as androgens (DHEA-S)48 or, as observed for other steroidogenic enzymes,49 other molecular substrates altogether.

The implications of our findings on the potential of STS inhibition as a therapeutic approach in breast cancers are also problematic. To date preclinical and clinical studies examining STS inhibition in ER positive breast cancers have shown beneficial outcomes; reduced tumour growth and proliferation in pre-clinical models14,15,50 and reduced proliferation, steroid levels and prolonged patient survival in clinical trials.18,19,51,52 Limited tests have also been done in the preclinical setting for ER negative breast cancers (MDA-MB-231 cell line, TNBC subtype) with similar promising findings.53 To the best of our knowledge no tests have been carried out in HER2 models or patients. The best explanation that we can offer to resolve our findings of STS expression being associated with beneficial survival outcomes across breast cancer subtypes, yet STS inhibition being beneficial as detailed above is similar to the explanation offered for the actions of oestrogen inhibition in ERα positive breast cancer or androgen inhibition in AR positive ERα negative breast cancer. This is while the expression of the protein (in this case STS) identifies a cancer with a less aggressive phenotype, thus better survival (e.g., better survival in ERα positive breast cancer vs negative, e.g., Viale et al., 54 better survival in AR positive TNBC vs negative55 inhibition of that protein may cause growth arrest and thus be beneficial in the long term to patient outcomes. While much of this is speculative, it highlights the importance of further investigation into STS actions and roles in breast cancer to clarify these and other issues.

Beyond the effect on survival observed with STS and 17βHSD2, other important expressions and correlations were observed. Firstly aromatase and ERβ expression were correlated suggesting an interaction between the expressions of these two proteins. While this is logically intuitive there is little data previously reporting this relationship in breast cancers. Given the very different transcriptional program enacted by ERα and ERβ (reviewed in5 it is potentially significant for the underlying biology to consider that the impact of aromatase may differ depending on the dominant oestrogen receptor present in the individual carcinoma. Secondly, the data presented in this paper also demonstrated widespread expression of both the AR and GR across breast cancer subtypes. In line with previous reports, AR expression was reduced in the TNBC subtype, albeit with our data at the upper range of what has previously been reported. It is important to note that a subset of TNBC cases retain AR expression both in our dataset and in the literature, and this may be of clinical significance (reviewed in.23,56 GR expression has likewise previously been shown to be expressed at comparative levels in breast cancers.57 Although non-significant, the sign of both AR and GR regression coefficients suggests a correlation with worse outcome which is consistent with some but not all reports in the literature. While the data from this study did not provide strong evidence as to their biological roles in carcinomas, previous studies have suggested their potential importance to breast cancer biology (reviewed in.5,27 Their presence in the tumour across subtypes in this study is of note and should be factored in future investigations.

Conclusions

The data presented in this paper highlights the presence and complexity of the extended endocrine/intracrine environment of breast cancers. This extended endocrine/intracrine environment is demonstrated by the presence of an expanded panel of nuclear receptors (AR, GR, and ERβ1), as well as the multitude of steroid metabolising enzymes that can interconvert steroid already present in the tumour or make additional pools of circulating steroid available to the tumour. The most striking finding was the existence of a beneficial effect of STS expression in the primary tumour on both local and distal recurrences and on survival. Less striking, but no less important is the data demonstrating that this extended endocrine/intracrine environment exists across breast cancer subtypes including the HER2-positive and TNBC designations. This further understanding may, in the long run, form a keystone in optimising the endocrine treatment of human breast cancer.

Electronic supplementary material

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41416-018-0034-9.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2016.html (2016).

- 2.Geisler J, Lonning PE. Aromatase inhibition: translation into a successful therapeutic approach. Clin. Cancer Res.: Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2005;11:2809–2821. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baselga J, et al. Phase II study of weekly intravenous trastuzumab (Herceptin) in patients with HER2/neu-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. Semin. Oncol. 1999;26:78–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lonning PE, et al. Tissue estradiol is selectively elevated in receptor positive breast cancers while tumour estrone is reduced independent of receptor status. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2009;117:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McNamara KM, Guestini F, Sakurai M, Kikuchi K, Sasano H. How far have we come in terms of oestrogens in breast cancer? Endocr. J. 2016;63:413–424. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ16-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sasano H, Miki Y, Nagasaki S, Suzuki T. In situ oestrogen production and its regulation in human breast carcinoma: from endocrinology to intracrinology. Pathol. Int. 2009;59:777–789. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2009.02444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suzuki M, et al. Expression level of enzymes related to in situ oestrogen synthesis and clinicopathological parameters in breast cancer patients. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2009;113:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takagi M, et al. Intratumoral oestrogen production and actions in luminal A type invasive lobular and ductal carcinomas. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2016;156:45–55. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-3739-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luu-The V, Zhang Y, Poirier D, Labrie F. Characteristics of human types 1, 2 and 3 17 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activities: oxidation/reduction and inhibition. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1995;55:581–587. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(95)00209-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nokelainen P, et al. Molecular cloning of mouse 17 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 and characterization of enzyme activity. Eur. J. Biochem. 1996;236:482–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al Sarakbi W, et al. The role of STS and OATP-B mRNA expression in predicting the clinical outcome in human breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:4985–4990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzuki T, et al. Oestrogen sulfotransferase and steroid sulfatase in human breast carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2762–2770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Utsumi T, et al. Steroid sulfatase expression is an independent predictor of recurrence in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1999;59:377–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foster PA, et al. A new therapeutic strategy against hormone-dependent breast cancer: the preclinical development of a dual aromatase and sulfatase inhibitor. Clin. Cancer Res.: Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2008;14:6469–6477. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foster PA, et al. Efficacy of three potent steroid sulfatase inhibitors: pre-clinical investigations for their use in the treatment of hormone-dependent breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2008;111:129–138. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9769-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geisler J, Sasano H, Chen S, Purohit A. Steroid sulfatase inhibitors: promising new tools for breast cancer therapy? J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2011;125:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maltais R, Poirier D. Steroid sulfatase inhibitors: a review covering the promising 2000–2010 decade. Steroids. 2011;76:929–948. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palmieri C, et al. IRIS study: a phase II study of the steroid sulfatase inhibitor Irosustat when added to an aromatase inhibitor in ER-positive breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017;165:343–353. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4328-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stanway SJ, et al. Phase I study of STX 64 (667 Coumate) in breast cancer patients: the first study of a steroid sulfatase inhibitor. Clin. Cancer Res.: Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2006;12:1585–1592. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ingle JN, et al. Combination hormonal therapy with tamoxifen plus fluoxymesterone versus tamoxifen alone in postmenopausal women with metastatic breast cancer. Update. Anal. Cancer. 1991;67:886–891. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910215)67:4<886::aid-cncr2820670405>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tormey DC, Lippman ME, Edwards BK, Cassidy JG. Evaluation of tamoxifen doses with and without fluoxymesterone in advanced breast cancer. Ann. Intern. Med. 1983;98:139–144. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-98-2-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McNamara K, et al. Androgenic pathway in triple negative invasive ductal tumours: its correlation with tumour cell proliferation. Cancer Sci. 2013;104:639–646. doi: 10.1111/cas.12121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McNamara KM, Moore NL, Hickey TE, Sasano H, Tilley WD. Complexities of androgen receptor signalling in breast cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2014;21:T161–T181. doi: 10.1530/ERC-14-0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glaser R, Dimitrakakis C. Testosterone and breast cancer prevention. Maturitas. 2015;82:291–295. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D’Amato NC, et al. Cooperative dynamics of AR and ER activity in breast cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. 2016;11:1054–1067. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-16-0167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McNamara K. M., Kannai A., Sasano H. Possible roles for glucocorticoid signalling in breast cancer. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. pii: S0303-7207(17)30358-1 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.McNamara KM, Sasano H. Beyond the C18 frontier: androgen and glucocorticoid metabolism in breast cancer tissues: the role of non-typical steroid hormones in breast cancer development and progression. Steroids. 2015;103:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan D, Kocherginsky M, Conzen SD. Activation of the glucocorticoid receptor is associated with poor prognosis in oestrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6360–6370. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marschke KB, Tan JA, Kupfer SR, Wilson EM, French FS. Specificity of simple hormone response elements in androgen regulated genes. Endocrine. 1995;3:819–825. doi: 10.1007/BF02935687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sahu B, et al. Dual role of FoxA1 in androgen receptor binding to chromatin, androgen signalling and prostate cancer. EMBO J. 2011;30:3962–3976. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Swinstead EE, et al. Steroid receptors reprogram FoxA1 occupancy through dynamic chromatin transitions. Cell. 2016;165:593–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McNamara KM, et al. The presence and impact of oestrogen metabolism on the biology of triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017;161:213–227. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-4050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McNamara KM, et al. Androgen receptor and enzymes in lymph node metastasis and cancer reoccurrence in triple-negative breast cancer. Int. J. Biol. Markers. 2015;30:e184–e189. doi: 10.5301/jbm.5000132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McNamara KM, et al. Androgenic pathways in the progression of triple-negative breast carcinoma: a comparison between aggressive and non-aggressive subtypes. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2014;145:281–293. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2942-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suzuki T, et al. 17Beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 and type 2 in human breast carcinoma: a correlation to clinicopathological parameters. Br. J. Cancer. 2000;82:518–523. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.0956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vachon CM, et al. Aromatase immunoreactivity is increased in mammographically dense regions of the breast. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011;125:243–252. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0944-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.R Development Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2015).

- 38.Yang XR, et al. Hormonal markers in breast cancer: coexpression, relationship with pathologic characteristics, and risk factor associations in a population-based study. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10608–10617. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Evans TR, Rowlands MG, Law M, Coombes RC. Intratumoral oestrone sulphatase activity as a prognostic marker in human breast carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer. 1994;69:555–561. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Newman SP, Purohit A, Ghilchik MW, Potter BV, Reed MJ. Regulation of steroid sulphatase expression and activity in breast cancer. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2000;75:259–264. doi: 10.1016/S0960-0760(00)00177-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simoes BM, et al. Effects of oestrogen on the proportion of stem cells in the breast. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011;129:23–35. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Korkaya H, Wicha MS. HER2 and breast cancer stem cells: more than meets the eye. Cancer Res. 2013;73:3489–3493. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marotti JD, Collins LC, Hu R, Tamimi RM. Oestrogen receptor-beta expression in invasive breast cancer in relation to molecular phenotype: results from the Nurses’ Health Study. Mod. Pathol.: Off. J. US Can. Acad. Pathol. Inc. 2010;23:197–204. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nelson AW, et al. Comprehensive assessment of oestrogen receptor beta antibodies in cancer cell line models and tissue reveals critical limitations in reagent specificity. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2016;15:138–150. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2016.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andersson S, et al. Insufficient antibody validation challenges oestrogen receptor beta research. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15840. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tan W, et al. Oestrogen receptor beta as a prognostic factor in breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:10373–10385. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weihua Z, Lathe R, Warner M, Gustafsson JA. An endocrine pathway in the prostate, ERbeta, AR, 5alpha-androstane-3beta,17beta-diol, and CYP7B1, regulates prostate growth. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:13589–13594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162477299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Billich A, Nussbaumer P, Lehr P. Stimulation of MCF-7 breast cancer cell proliferation by estrone sulfate and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate: inhibition by novel non-steroidal steroid sulfatase inhibitors. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2000;73:225–235. doi: 10.1016/S0960-0760(00)00077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Byrns MC, Penning TM. Type 5 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/prostaglandin F synthase (AKR1C3): role in breast cancer and inhibition by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug analogs. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2009;178:221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Foster PA, et al. In vivo efficacy of STX213, a second-generation steroid sulfatase inhibitor, for hormone-dependent breast cancer therapy. Clin. Cancer Res.: Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2006;12:5543–5549. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Palmieri C, et al. IPET study: an FLT-PET window study to assess the activity of the steroid sulfatase inhibitor irosustat in early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017;166:527–539. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4427-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coombes RC, et al. A phase I dose escalation study to determine the optimal biological dose of irosustat, an oral steroid sulfatase inhibitor, in postmenopausal women with oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2013;140:73–82. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2597-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leese MP, et al. Structure-activity relationships of C-17 cyano-substituted estratrienes as anticancer agents. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:1295–1308. doi: 10.1021/jm701319c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Viale G, et al. Immunohistochemical versus molecular (BluePrint and MammaPrint) subtyping of breast carcinoma. Outcome results from the EORTC 10041/BIG 3-04 MINDACT trial. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017;167:123–131. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4509-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang C, et al. Prognostic value of androgen receptor in triple negative breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:46482–46491. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McNamara KM, et al. Androgen receptor in triple negative breast cancer. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2013;133:66–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abduljabbar R, et al. Prognostic and biological significance of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma in luminal breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2015;150:511–522. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.