Abstract

Objective

To evaluate two strategies for preparing family members for surrogate decision-making.

Design

2×2 factorial, randomized controlled trial testing whether: 1) comprehensive online advance care planning (ACP) is superior to basic ACP, and 2) having patients engage in ACP together with family members is superior to ACP done by patients alone.

Setting

Tertiary care centers in Hershey, PA and Boston, MA.

Participants

Dyads of patients with advanced, severe illness (mean age 64; 46% female; 72% white) and family members who would be their surrogate decision-makers (mean age 56; 75% female; 75% white).

Interventions

Basic ACP: State-approved online advance directive plus brochure. Making Your Wishes Known (MYWK): Comprehensive ACP decision aid including education and values clarification.

Measurements

Pre-post changes in family member self-efficacy (100-point scale), and post-intervention concordance between patients and family members using clinical vignettes.

Results

285 dyads enrolled; 267 patients and 267 family members completed measures. Baseline self-efficacy in both MYWK and Basic ACP groups was high (90.2 and 90.1, respectively), and increased post-intervention to 92.1 for MYWK (p=0.13) and 93.3 for Basic ACP (p=0.004), with no between-group difference. Baseline self-efficacy in Alone and Together groups was also high (90.2 and 90.1, respectively), and increased to 92.6 for Alone (p=0.03) and 92.8 for Together (p=0.03), with no between-group difference. Overall adjusted concordance was higher in MYWK compared to Basic ACP (85.2% vs 79.7%; p=0.032), with no between-group difference.

Conclusion

The disconnect between confidence and performance raises questions about how to prepare family members to be surrogate decision-makers.

Keywords: Advance Care Planning, surrogate decision-making, self-efficacy, family caregivers

Introduction

Each year, 2.5 million people die in the U.S., and 70% lack decision-making capacity at the end of life.1 When patients are too ill to make medical decisions, family members typically serve as surrogate decision-makers.1,2 But family members often feel ill-prepared for this role, describing such life and death decisions as extraordinarily stressful and emotionally burdensome,3–8 with the distress sometimes exceeding that experienced by survivors of natural disasters, construction accidents, and home fires.9 In one ICU-based study 82% of surrogates suffered post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms,10 and a meta-analysis found that the burden of surrogate decision-making is widespread and long-lasting.8 Though family members experience distress for many reasons,11–13 often overlooked is their inadequate preparation for becoming a surrogate decision-maker.

Efforts to prepare family members to become surrogates have included “do not escalate treatment” orders,14 designating a single point of contact for the medical team,15 encouraging family members to be present for clinical rounds,16 and involving nurse specialists in ICU family meetings.17 What has not been explored is the use of online tools for advance care planning (ACP) that include both patients and their family members.

Previously, we described a comprehensive online decision aid, Making Your Wishes Known (MYWK), that guides people through the process of ACP,18 increases knowledge about ACP, and helps users make decisions that are more consistent with their values, goals, and preferences.19–21 MYWK also helps healthcare providers better understand what future medical treatments patients would want.20 The present study focused on surrogate decision-making, seeking to understand whether use of MYWK was more effective than basic ACP, and whether ACP by patients and family members together was more effective than ACP done by patients alone. For clarity, we use the term “family member” to refer to individuals (related or close friends) identified by patients as potential surrogate decision-makers. Only after the family member makes a decision on behalf of a patient are they referred to as “surrogates.”

Methods

Study Design

This 2×2 randomized controlled trial at two tertiary care medical centers compared family members’ preparedness to make surrogate medical decisions after patients engaged in advance care planning using MYWK vs Basic ACP, and when patients did so Alone vs Together with their family member (Group 1 = Basic ACP Materials/Patient Alone; Group 2 = MYWK/Patient Alone; Group 3 = Basic ACP Materials/Patient and Family Member Together; and Group 4 = MYWK/Patient and Family Member Together). Hypothesis #1 was that family members in Groups 2 and 4 (MYWK Groups) would be better-prepared than those in Groups 1 and 3 (defined by greater self-efficacy and higher concordance between family members’ decisions and patients’ wishes). Hypothesis #2 was that ACP done with family members and patients together (Groups 3 and 4) would be superior to ACP done by patients alone (Groups 1 and 2), in terms of family member self-efficacy and concordance. Enrollment took place between August 2013 and June 2016 at Penn State Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, PA, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Boston, MA, and was approved by IRBs at participating sites. The trial was registered at ClincialTrials.gov (#NCT02429479).

Study Population

The study population consisted of dyads of patients with an advanced, severe illness22 and family members (who would become surrogate decision-makers in the event of decisional incapacity). Patients were eligible if they were ≥18 years, and had: moderate/severe heart failure (i.e. Class III or Class IV as per NYHA);23 chronic lung disease (i.e. Stage 3 or Stage 4 COPD per modified GOLD Classification); end stage renal disease (i.e. chronic kidney disease Stage 4 or 5 per National Kidney Foundation); or advanced cancer (i.e. Stage IV disease or estimated survival of ≤2 years). The Boston site exclusively recruited under-represented racial/ethnic minorities. Lists of potential patient-participants were compiled by prospectively reviewing clinic records, from which referring physicians (or their appointees) confirmed: 1) the patient had a qualifying disease, and 2) “it wouldn’t surprise you if (within 18 months) the patient had to rely on a family member to make a major medical decision on their behalf.”

Potential patient-participants were sent a letter of introduction and opt-out postcard. When feasible, research staff met with eligible patients in clinic. If no opt-out letter was returned, the patient was invited by phone to participate and asked to identify a potential surrogate who was ≥18 years of age and had in-person contact with them at least weekly. After the study was explained to patients and potential surrogates, these dyads were scheduled for a study visit. Basic demographic information was collected from study decliners for comparison. Participants received a $50 gift certificate at completion of study visits.

Study Interventions

Basic ACP

Participants in this group were provided with educational materials developed by the American Hospital Association24 and an online version of a simple advance directive (AD) identified as being one of the best in the US.25 The AD consists of a living will form plus a prompt to select a spokesperson/surrogate. It includes brief instructions followed by space to specify whether they wish to always prolong life or to sometimes not prolong life. If the latter, users provide specific treatment directions under circumstances of an end-stage medical condition or permanent unconsciousness. Unlike MYWK (described below), there are no values clarification exercises, education about medical conditions/treatments, or decision aid. Prior research showed that users spend, on average, 26 minutes (range 10-65 minutes) to complete this AD.19

Making Your Wishes Known

Participants in the intervention group used Making Your Wishes Known (MYWK), a comprehensive, interactive, online decision aid for ACP (www.makingyourwishesknown.com) developed by a multidisciplinary team with expertise in medicine, geriatrics, nursing, decision analysis, law, and instructional design. MYWK was created to be user-friendly and educational, and includes audio and video simulating a conversation with a healthcare provider. The program provides tailored education (8th grade reading level) about common medical conditions that can result in decisional incapacity, as well as treatments introduced in life-or-death situations. To help with difficult decisions, the program asks users to rank and rate the importance of factors that influence choices, using a framework based on multi-attribute utility theory.26–29 Studies with diverse populations21,30,31 have demonstrated that MYWK is easy to use,31 effective for improving knowledge about end-of-life medical decisions,19 accurate in representing patients’ wishes,20 and helpful to clinicians.32 Prior research showed that users spend, on average, 70 minutes (range 15-120 minutes) to complete MYWK.19

Study Protocol

During Study Visit 1, following informed consent, patients and family members were screened for neuro-cognitive capacity (>23 on Folstein Mini Mental State Exam)33 and 8th grade reading level (able to read to 26th word on WRAT-3).34 Patients were also screened for suicidal ideations (Beck Depression Inventory-II),35 and referred to a psychologist or psychiatrist if severely depressed or suicidal (none were). Individuals not meeting screening criteria received a gift certificate and the opportunity to complete an AD, but study data were not recorded. Patients were excluded for moderate/severe depression during the first two years of the study, but this restriction was discontinued after establishing that such patients could complete the study without undue distress.

Eligible dyads were randomized into four groups: 1) Basic ACP/Patient Alone; 2) MYWK/Patient Alone; 3) Basic ACP/Patient and Family Member Together; and 4) MYWK/Patient and Family Member Together. Randomization included three stratification factors: patient disease (heart, kidney, lung, or cancer), family member gender,36,37 and study site (Boston or Hershey). In the “Together” groups, participants shared one computer, with the family member sitting beside the patient and assisting with the intervention. In the “Alone” groups, patients completed the intervention singlehandedly, while the family members waited in a separate room. ACP was carried out at the study site and research assistants verified that the intervention was completed. Dyads returned 3-5 weeks later for Study Visit 2. Participants knew if they were completing the intervention Together vs Alone, but were blinded as to intervention group. To avoid unconscious bias, researchers did not review participants’ group designation when gathering Visit 2 data (though not formally blinded). To further safeguard data integrity, the Principal Investigators had no access to individual data and no knowledge of participants’ enrollment group when interpreting results.

Study Outcomes

The primary outcomes were whether family members felt prepared to serve as surrogate decision makers (self-efficacy), and whether they were prepared to accurately represent patients’ wishes (concordance). Self-efficacy was assessed pre- and post-intervention using a modified version of Nolan’s 17-item scale38 based on Bandura’s framework.39 This instrument (available as Supplementary Figure S1) quantifies family members’ confidence (0-100, where 100=greatest self-efficacy) in accomplishing tasks associated with surrogate decision-making (e.g., determining specific treatments, overcoming communication barriers, and honoring patient’s wishes). Concordance was assessed using six previously tested clinical vignettes40 involving situations where major medical decisions needed to be made (CPR, mechanical ventilation, surgery, hemodialysis, feeding tube, and IV antibiotics). Patients indicated which treatments they would or wouldn’t want in each scenario, and family members separately were asked “if you had to decide now what medical treatments your loved one would want in the circumstances described, which of the following do you think he/she would want and not want?” (see Supplementary Figure S2).

An overall concordance score was calculated by summing the number of treatment decisions for which patient and family members’ responses were identical, and dividing by the total number of decisions (n=28), all equally weighted (score range 0–28), and multiplying by 100 (score range 0-100%) (see Supplementary Figure S3). Additionally, concordance scores were calculated for the 28 separate treatment decisions.

Demographic information was collected from patients and family members, including age, gender, race, education, religion, ethnicity, marital status, employment status, computer use, and prior experience with ACP and/or surrogate decision-making. These measures were later analyzed as potential confounders.

Sample Size and Statistical Analysis

We estimated 200 dyads would be needed to detect a 5 point difference in self-efficacy scores between groups, with a two-tailed α of 0.05 and a power (1-β) of 0.80. To compensate for potential attrition, we enrolled 285 dyads.

For this 2×2 study design, analyses were conducted on data from all participants who completed Study Visits 1 and 2. A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test change in self-efficacy pre- to post-intervention between group means. This was done to compare basic ACP vs. MYWK, and again to compare Alone vs. Together groups. This same approach was used for concordance scores, although concordance was not analyzed for change, as it was measured only at Visit 2. For specific treatment concordance, the same main effects were tested using logistic regression, and odds ratios quantified the direction and magnitude of the likelihood of concordance. An interaction term between the two main effects was tested in all models but was not significant. The analysis included models both unadjusted and adjusted for potential confounders, including prior completion of AD by patient or family member, patient disease category, study site, patient race and ethnicity. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Cohort demographics

Between August, 2013 and June, 2016, 285 patient-family member dyads were eligible and randomized, and 267 (93.7%) completed both Study Visits 1 and 2 and were included in the analysis (207 from Hershey and 60 from Boston). The refusal rate was 50% and exclusion rate was 38%. [Figure 1, Study Design and Consort Flow Chart]

Figure 1.

Study Design and Consort Flow Chart

For both patients and family members, baseline characteristics were similar in all four groups (see Supplementary Table S4 for detailed demographics). Because we did not see any significant overall differences in education level between groups, we did not examine differences in outcomes based on education; however, participants in Alone Group were more likely to have previously completed an AD (36.5% vs 24.1%, p=0.027). Compared to participants (n=267), non-participants who completed decliner surveys (n=378) were less educated (48.1% education beyond HS vs. 62.1%, p=0.02), more likely to already have completed an AD (60.0% vs. 45.8%, p=0.001), and less confident in their computer skills (3.8 vs 4.5 on a 1-7 scale, p=0.02). [Table 1, Demographics]

Table 1.

Study Participant Demographics

| Characteristics | Patients (n=267) |

Family Members (n=267) |

Overall (n= 534) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, female N (%) | 122 (45.7) | 201 (75.3) | 323 (60.5) |

| Age, mean ± SD, years | 63.8 ± 13.4 | 55.9 ± 13.9 | 59.9 ± 14.2 |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | |||

| Hispanic | 11 (4.3) | 12 (4.6) | 23 (4.5) |

| Black | 50 (19.7) | 44 (17.0) | 94 (18.3) |

| White | 183 (72.1) | 195 (75.3) | 378 (73.7) |

| Other | 10 (3.9) | 8 (3.1) | 18 (3.5) |

| Patient Disease Category (%) | |||

| Cardiac | 72 (27.0) | ||

| Pulmonary | 61 (22.9) | ||

| Cancer | 83 (31.1) | ||

| Renal | 51 (19.1) | ||

| Education (%) | |||

| <8th grade | 7 (2.6) | 2 (0.8) | 9 (1.7) |

| Some HS | 16 (6.0) | 8 (3.0) | 24 (4.5) |

| HS or GED | 78 (29.3) | 65 (24.3) | 143 (26.8) |

| Some College or tech | 83 (31.2) | 86 (32.2) | 169 (31.7) |

| College Grad | 42 (15.8) | 63 (23.6) | 105 (19.7) |

| Graduate School | 40 (15.0) | 43 (16.1) | 83 (15.6) |

| Marital Status (%) | |||

| Never married | 31 (11.7) | 38 (14.3) | 69 (13.0) |

| Married | 166 (62.6) | 184 (69.2) | 350 (65.9) |

| Divorced/separated | 31 (11.7) | 22 (8.3) | 53 (10.0) |

| Widowed | 27 (10.2) | 10 (3.8) | 37 (7.0) |

| Domestic Partnership | 6 (2.3) | 9 (3.4) | 15 (2.8) |

| Other | 4 (1.5) | 3 (1.1) | 7 (1.3) |

| Prior experience with ACP (%)* | |||

| Almost none | 26 (9.8) | 34 (12.7) | 60 (11.3) |

| A little | 98 (36.8) | 97 (36.3) | 195 (36.6) |

| A fair amount | 96 (36.1) | 95 (35.6) | 191 (35.8) |

| A lot | 46 (17.3) | 41 (15.4) | 87 (16.3) |

| Already have an AD† | 121 (45.8) | 80 (30.0) | 201 (37.9) |

| Assigned a Proxy | 152 (58.0) | 102 (38.5) | 254 (48.2) |

| Helped someone else prepare AD | 55 (20.8) | 80 (30.3) | 135 (25.6) |

| Helped a family member with medical decision making | 186 (69.9) | ||

| Prior ACP conversations | |||

| “The patient is my…” | |||

| Spouse/partner | 152 (56.9) | ||

| Parent | 64 (24.0) | ||

| Sibling | 9 (3.4) | ||

| Son/Daughter | 11 (4.1) | ||

| Other | 31 (11.6) | ||

| Lives with patient | 182 (68.4) | ||

| Own a computer (%) | 194 (73.8) | 222 (83.2) | |

| Hours/week using computer, median (Q1, Q3) | 6.0 (1.0, 15.0) | 10.0 (3.5, 30.0) | 8.0 (2.0, 20.0) |

“How much have you read or heard about advance care planning or living wills (i.e. documents that formally communicate your wishes regarding health care)?”

“Prior to enrollment in this study, had you prepared an advance directive/living will for yourself?”

Self-efficacy

Family members’ self-efficacy scores were high at baseline (>90 on a 0-100 scale, where 100=highest) in both the MYWK (90.2) and Basic ACP group (90.1). There was a slight post-intervention increase in both groups, which was significant in the Basic ACP Group (mean change=3.2, p=0.004).

Similarly, self-efficacy scores were high at baseline in both the Alone and Together groups. Again, there was a slight increase in self-efficacy post-intervention, but here the increase was significant in both groups (adjusted mean increase=2.3 for Alone and 2.5 for Together, p=0.033 and p=0.026, respectively). [Table 2, Self-Efficacy and Concordance]

Table 2.

Self-Efficacy and Concordance

| Self-Efficacy (pre to post change by group) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | N | Pre-Intervention | Post-Intervention | Raw Mean Change | Adjusted Mean Change* | P-value (within)* | P-value (between)* |

| Basic ACP | 135 | 90.1 (88.3, 91.8) |

93.3 (92.2, 94.4) |

3.2 (1.7, 4.7) |

3.2 (1.0, 5.3) |

0.004 | 0.054 |

| MYWK | 132 | 90.2 (88.5, 91.9) |

92.1 (90.6, 93.7) |

2.0 (0.9, 3.1) |

1.7 (−0.5, 3.9) |

0.134 | |

| Alone | 126 | 90.2 (88.3, 92.1) |

92.6 (81.4, 93.9) |

2.5 (1.0, 4.0) |

2.3 (0.2, 4.5) |

0.033 | 0.823 |

| Together | 141 | 90.1 (88.6, 91.6) |

92.8 (91.4, 94.2) |

2.7 (1.5, 3.9) |

2.5 (0.3, 4.7) |

0.026 | |

| Concordance (percentage of questions where patients and family members agree) | |||||||

| Group | N |

Raw (% agreement) |

Adjusted (% agreement)* |

P-Value (between)* | |||

| Basic ACP | 135 | 70.8 (67.3, 74.3) |

79.7 (72.7, 86.8) |

0.032 | |||

| MYWK | 132 | 76.1 (72.8, 79.4) |

85.2 (77.9, 92.4) |

||||

| Alone | 126 | 72.3 (68.7, 75.8) |

80.6 (73.5, 87.7) |

0.149 | |||

| Together | 141 | 74.4 (71.1, 77.8) |

84.3 (77.0, 91.5) |

||||

Two-way ANOVA adjusted for the pre-measurement and confounders: prior completion of advance directive, disease, study site, race/ethnicity

Concordance

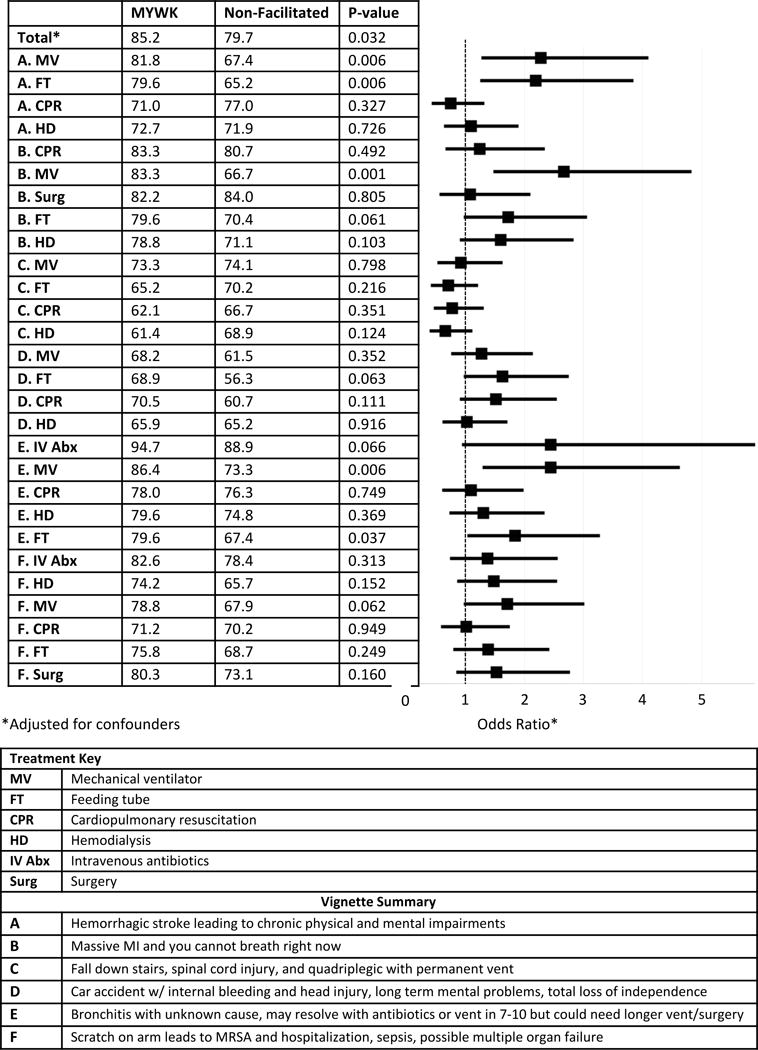

The overall adjusted concordance score was higher in the MYWK group compared to the Basic ACP group (85.2% vs 79.7%; p=0.032). For specific medical treatments, concordance scores were generally higher in the MYWK group than the Basic ACP group, reaching significance in individual vignettes for questions about mechanical ventilation and feeding tube placement. [Figure 2, Concordance Comparisons by Vignette]

Figure 2.

Concordance Comparison by Vignette

Comparing the Alone vs. Together groups, there were no significant differences in either overall concordance scores, or concordance scores for decisions within individual vignettes (Table 2).

Discussion

As hypothesized, family members more accurately predicted patients’ wishes (i.e., higher concordance) after using the comprehensive decision aid (MYWK) compared to Basic ACP materials. Surprisingly, however, this increase in concordance was not matched by a significant increase in self-efficacy in the MYWK Group, whereas those in the Basic ACP group did report greater self-efficacy.

What accounts for this unexpected finding? One possible explanation was keenly articulated 150 years ago by Charles Darwin, who observed that “ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge”.41 This adage may help explain why family members whose loved ones engaged in basic ACP felt more confident yet were less accurate at representing patients’ wishes than family members whose loved ones engaged in the more systematic and detailed MYWK. This particular cognitive bias was described by Dunning and Kruger who showed that people tend to hold overly favorable views of their abilities and, paradoxically, that improving individuals’ awareness of the skills needed to successfully complete a task can result in decreased self-efficacy because people better recognize the limitations of their abilities.42

It is also worth noting that baseline self-efficacy scores were higher than expected for all family members,38 which may constitute a ceiling effect that artificially restricts scores at the higher end, limiting potential gains in self-efficacy.43 In light of research showing that family members/surrogates are not actually well-prepared for making major medical decisions,44–46 participants’ high baseline confidence may be unwarranted.

Perhaps more perplexing is the finding that ACP involving patients and family members Together did not yield superior concordance compared to ACP done by patients Alone. A foundational premise of ACP is that by promoting communication between patients and their loved ones, potential surrogates will have a better understanding of patients’ wishes.8,47 So, it is counterintuitive that family members engaging in ACP side-by-side with patients would not have higher concordance scores. Though other researchers have looked at patient-surrogate concordance in the context of advance care planning, this is the first large study to evaluate the impact of a decision aid on such concordance, and no prior studies compare ACP performed together versus alone.48–51 Possible explanations for our negative findings include that: 1) study participation –regardless of study arm-- itself prompted discussions that informed family members about patients’ wishes; 2) family members did not consider patients’ wishes when making hypothetical treatment decisions; and 3) people enrolling in this study, by definition, identified family members who they trusted to represent them, leaving less opportunity for improving concordance. Our study was not designed to assess such possibilities, but future research might examine this.

The study also raises broader questions about the overall value of targeting potential surrogates with ACP interventions. MYWK was scrupulously designed to follow evidence-based guidelines for decision aids,52 and prior research has shown that it improves both patients’ knowledge about ACP as well as healthcare providers’ understanding of patients’ wishes.40 Yet, when used with family members, the increase in concordance was less than anticipated. Why? It is, of course, possible that the intervention isn’t beneficial; but multiple studies suggest otherwise, including data on accuracy,20,30 knowledge,19,53 and concordance20,40 – which leads us to ponder other explanations. Perhaps the measures were inappropriate. Or, maybe family members require a different type of intervention than patients and healthcare providers. More radically, one might ask whether ACP interventions should target potential surrogates at all. We don’t yet know which, if any, of these explanations account for our findings, thus additional research should address the surprising results that emerged from this large, systematic study of over 250 patients with severe, life-threatening illness and their named potential surrogates.

Limitations

Enrollment was challenging due to the inherent difficulty of recruiting severely ill patients and their family members into a non-therapeutic study on an uncomfortable topic, raising the possibility of selection bias. That said, the randomized controlled design helps mitigate bias, our enrollment rate is similar to other published studies on ACP,54 and there were no differences between participants and decliners in terms of age, gender, or prior experience helping others complete ADs. Second, most non-participants did not complete decliner surveys, and among those who did, decliners had lower education and less confidence in their computer skills than participants. Further, participants tended to be well-educated and had prior experience with ACP. Taken together, the study may have a selection bias that limits generalizability. Third, the surprisingly high baseline self-efficacy scores left little room for improvement, and are contrary to prior research.38 Had participants expressed lower baseline self-efficacy, the interventions may have shown a greater effect. Fourth, the concordance was based on a single post-intervention measure (rather than pre-post comparison), hence we cannot rule out an imbalance between study groups with regard to concordance. The rationale for this approach was that introducing the vignettes prior to the intervention risked introducing bias insofar as the vignettes themselves could constitute an ACP intervention. Finally, concordance scores were higher than in prior research, which may be attributable to the large proportion of patients and family members who reported previous experience with ACP and surrogate decision-making.

Conclusions

The present findings raise foundational questions about how best to prepare family members for their role as surrogate decision-makers. While a comprehensive decision aid did improve family members’ knowledge of patients’ wishes, there was no correlation between such knowledge and confidence, nor did having family members engage in ACP together with patients have any discernable effect. We cannot assume that interventions shown to be effective for patients and clinicians are likewise effective for potential surrogate decision-makers.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure S1: Self-Efficacy Instrument.

Supplementary Figure S2: Patient Vignettes.

Supplementary Figure S3: Vignette Concordance Score Sheet.

Supplementary Table S4: Participant Demographics by Study Group.

Acknowledgments

Sponsor’s Role: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health, under Award Number 5R01NR012757. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessary represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Veterans Administration. The sponsor played no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis or preparation of the paper.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests: Two of the authors (BHL & MJG) have intellectual property and copyright interests for the comprehensive decision aid used in this study, Making Your Wishes Known: Planning Your Medical Future (MYWK), which is available online free of charge. A version of MYWK that can be widely distributed is currently under development in partnership with a private commercial enterprise.

- Michael J. Green: study concept and design; methods analysis and interpretation of data; preparation of paper

- Lauren J. Van Scoy: analysis and interpretation of data; preparation of paper

- Andrew J. Foy: analysis and interpretation of data; preparation of paper

- Renee R. Stewart: subject recruitment and data collection; preparation of paper

- Ramya Sampath: subject recruitment and data collection; preparation of paper

- Jane R. Schubart: methods; analysis and interpretation of data; preparation of paper

- Erik B. Lehman: study design; statistical analysis

- Anne E.F. Dimmock: subject recruitment and data collection; preparation of paper

- Ashley M. Bucher: subject recruitment and data collection; preparation of paper

- Lisa Soleymani Lehmann: study concept and design; analysis and interpretation of data; preparation of paper

- Alyssa F. Harlow: subject recruitment and data collection; preparation of paper

- Chengwu Yang: study design; statistical analysis

- Benjamin H. Levi: study concept and design; methods; analysis and interpretation of data; preparation of paper

References

- 1.Silveira MJ, Kim SYH, Langa KM. Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(13):1211–1218. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0907901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raymont V, Bingley W, Buchanan A, et al. Prevalence of mental incapacity in medical inpatients and associated risk factors: cross-sectional study. The Lancet. 2004;364(9443):1421–1427. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17224-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bevan JL, Pecchioni LL. Understanding the impact of family caregiver cancer literacy on patient health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;71(3):356–364. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirschman KB, Kapo JM, Karlawish JH. Why doesn’t a family member of a person with advanced dementia use a substituted judgment when making a decision for that person? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(8):659–667. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000203179.94036.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meeker MA, Jezewski MA. A voice for the dying. Clin Nurs Res. 2004;13(4):326–342. doi: 10.1177/1054773804267725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meeker MA, Jezewski MA. Family decision making at end of life. Palliat Support Care. 2005;3(2):131–142. doi: 10.1017/s1478951505050212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grunfeld E, Coyle D, Whelan T, et al. Family caregiver burden: results of a longitudinal study of breast cancer patients and their principal caregivers. CMAJ. 2004;170(12):1795–1801. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wendler D, Rid A. Systematic review: the effect on surrogates of making treatment decisions for others. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(5):336–346. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-5-201103010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tilden VP, Tolle SW, Nelson CA, Fields J. Family decision-making to withdraw life-sustaining treatments from hospitalized patients. Nurs Res. 2001;50(2):105–115. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200103000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(9):987–994. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iverson E, Celious A, Kennedy CR, et al. Factors affecting stress experienced by surrogate decision makers for critically ill patients: implications for nursing practice. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2014;30(2):77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McAdam JL, Puntillo K. Symptoms experienced by family members of patients in intensive care units. Am J Crit Care. 2009;18(3):200–209. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2009252. quiz 210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petrinec AB, Daly BJ. Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms in Post-ICU Family Members: Review and Methodological Challenges. West J Nurs Res. 2016;38(1):57–78. doi: 10.1177/0193945914544176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobsen J, Billings A. Easing the burden of surrogate decision making: the role of a do-not-escalate-treatment order. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(3):306–309. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vig EK, Starks H, Taylor JS, Hopley EK, Fryer-Edwards K. Surviving surrogate decision-making: what helps and hampers the experience of making medical decisions for others. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1274–1279. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0252-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davidson JE, Powers K, Hedayat KM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004–2005. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):605–622. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254067.14607.EB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White DB, Cua SM, Walk R, et al. Nurse-led intervention to improve surrogate decision making for patients with advanced critical illness. Am J Crit Care. 2012;21(6):396–409. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2012223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green MJ, Levi BH. Development of an interactive computer program for advance care planning. Health Expect. 2009;12(1):60–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2008.00517.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green MJ, Schubart JR, Whitehead MM, Farace E, Lehman E, Levi BH. Advance Care Planning Does Not Adversely Affect Hope or Anxiety Among Patients With Advanced Cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49(6):1088–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.11.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levi BH, Heverley SR, Green MJ. Accuracy of a decision aid for advance care planning: simulated end-of-life decision making. J Clin Ethics. 2011;22(3):223–238. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hossler C, Levi BH, Simmons Z, Green MJ. Advance care planning for patients with ALS: feasibility of an interactive computer program. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2011;12(3):172–177. doi: 10.3109/17482968.2010.509865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernacki RE, Block SD, American College of Physicians High Value Care Task F Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(12):1994–2003. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dolgin M. Nomenclature and criteria for diagnosis of diseases of the heart and great vessels. 9th. Little Brown and Company; Boston, MA USA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Hospital Association. Put it in Writing: Questions and Answers on Advance Directives. American Hospital Association; 1998. revised 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Last Acts. Means to a Better End: A Report on Dying in America Today. Washington DC: Last Acts; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chapman GB, Elstein AS, Kuzel TM, Nadler RB, Sharifi R, Bennett CL. A multi-attribute model of prostate cancer patient’s preferences for health states. Qual Life Res. 1999;8(3):171–180. doi: 10.1023/a:1008850610569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torrance GW, Boyle MH, Horwood SP. Application of multi-attribute utility theory to measure social preferences for health states. Oper Res. 1982;30(6):1043–1069. doi: 10.1287/opre.30.6.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Torrance GW, Feeny DH, Furlong WJ, Barr RD, Zhang Y, Wang Q. Multiattribute utility function for a comprehensive health status classification system. Health Utilities Index Mark 2. Med Care. 1996;34(7):702–722. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199607000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Torrance GW, Furlong W, Feeny D, Boyle M. Multi-attribute preference functions. Health Utilities Index. Pharmacoeconomics. 1995;7(6):503–520. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199507060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Markham SA, Levi BH, Green MJ, Schubart JR. Use of a Computer Program for Advance Care Planning with African American Participants. J Natl Med Assoc. 2015;107(1):26–32. doi: 10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30006-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Scoy LJ, Green MJ, Dimmock AE, et al. High satisfaction and low decisional conflict with advance care planning among chronically ill patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or heart failure using an online decision aid: A pilot study. Chronic Illn. 2016;12(3):227–235. doi: 10.1177/1742395316633511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green MJ, Brothers A, Whitehead M, et al. An advance care planning decision aid improves clinician understanding of the wishes of patients with ALS. European Association for Communication in Healthcare. International Conference on Communication in Healthcare; 2012; St. Andrews, Scotland. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cockrell J, Folstein M. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24(4):689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilkinson GS. WRAT-3: Wide range achievement test administration manual. Wilmington, DE: Wide Range; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beck A, Steer R, Brown G. Manual for Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) San Antonio, TX: Psychology Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arno PS, Levine C, Memmott MM. The economic value of informal caregiving. Health Aff (Millwood) 1999;18(2):182–188. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.2.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Navaie-Waliser M, Feldman PH, Gould DA, Levine C, Kuerbis AN, Donelan K. When the caregiver needs care: the plight of vulnerable caregivers. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(3):409–413. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.3.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nolan MT, Hughes MT, Kub J, et al. Development and validation of the Family Decision-Making Self-Efficacy Scale. Palliat Support Care. 2009;7(3):315–321. doi: 10.1017/S1478951509990241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bandura A. In: Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents. Pajares F, Urdan TC, editors. Greenwich, Conn.: IAP - Information Age Pub., Inc; 2006. p. xii.p. 367. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levi BH, Simmons Z, Hanna C, et al. Advance Care Planning for Patients with. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2017;18(5–6):388–396. doi: 10.1080/21678421.2017.1285317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Darwin C. The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. London: John Murray; 1871. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kruger J, Dunning D. Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77(6):1121–1134. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.6.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gall MD, Borg WR, Gall JP. Educational research: An introduction. 6. White Plains: Longman Publishers USA; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hickman RL, Jr, Daly BJ, Clochesy JM, O’Brien J, Leuchtag M. Leveraging the lived experience of surrogate decision makers of the seriously ill to develop a decision support intervention. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;30:67–69. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2015.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sullivan DR, Liu X, Corwin DS, et al. Learned helplessness among families and surrogate decision-makers of patients admitted to medical, surgical, and trauma ICUs. Chest. 2012;142(6):1440–1446. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Torke AM, Alexander GC, Lantos J. Substituted judgment: the limitations of autonomy in surrogate decision making. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(9):1514–1517. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0688-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Houben CH, Spruit MA, Groenen MT, Wouters EF, Janssen DJ. Efficacy of advance care planning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(7):477–489. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Austin CA, Mohottige D, Sudore RL, Smith AK, Hanson LC. Tools to Promote Shared Decision Making in Serious Illness: A Systematic Review. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1213–1221. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Butler M, Ratner E, McCreedy E, Shippee N, Kane RL. Decision aids for advance care planning: an overview of the state of the science. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(6):408–418. doi: 10.7326/M14-0644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oczkowski SJ, Chung HO, Hanvey L, Mbuagbaw L, You JJ. Communication Tools for End-of-Life Decision-Making in Ambulatory Care Settings: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PloS one. 2016;11(4):e0150671. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stacey D, Legare F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Volk RJ, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Stacey D, Elwyn G. Ten years of the International Patient Decision Aid Standards Collaboration: evolution of the core dimensions for assessing the quality of patient decision aids. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13(Suppl 2):S1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-S2-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Green MJ, Levi BH. Teaching advance care planning to medical students with a computer-based decision aid. J Cancer Educ. 2011;26(1):82–91. doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0146-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kolarik RC, Arnold RM, Fischer GS, Hanusa BH. Advance care planning. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(8):618–624. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10933.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure S1: Self-Efficacy Instrument.

Supplementary Figure S2: Patient Vignettes.

Supplementary Figure S3: Vignette Concordance Score Sheet.

Supplementary Table S4: Participant Demographics by Study Group.