Abstract

A positive safety culture is essential to patient safety because it improves quality of care. The aim of this study was to assess staff and student perceptions of the patient safety culture in the clinics of the College of Dentistry at King Saud University in Saudi Arabia.

A cross-sectional study was conducted in the College of Dentistry at King Saud University in Saudi Arabia. It included 4th and 5th year students, interns, general practitioners, and dental assistants. The data were collected by using paper-based questionnaire of modified version of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture. Data were entered into SPSS Version 20. Score on a particular safety culture dimension was calculated.

The overall response rate was 72.8% (390/536). Team work dimension had the highest average percent positive dimension score (72.3%) while staffing had the lowest score (10%). Dental assistant had high agreement in Teamwork dimension (87.8%); Supervisor/Manager Expectations and Actions Promoting Patient Safety dimension (66.9%); Organizational Learning—Continuous Improvement dimension (79.1%); Management Support for Patient Safety dimension (84.5%); Feedback and Communication About Error dimension (58.3%); Frequency of Events Reported dimension (54.0%); Teamwork Across Units dimension (73.2%). Most of areas perceived that there is no event reported (76.1-85.3%) in the past 12 months.

Overall patient safety grade is more than moderate in the clinic. Teamwork within Units and Organizational Learning—Continuous Improvement dimension had the highest score while staffing had the lowest score. Dental assistants perceived positive score in most dimensions while students perceived slight negative score in most dimensions.

Keywords: college of dentistry, dental clinic, patient safety culture

1. Introduction

Patient safety is a major concern for every member in the health care system. Preventing medical errors before causing harm to the patient is a priority in medicine. Investigation and studying of patient safety were initiated many years ago.[1] An example was when the British government established the confidential enquiry into maternal death in 1952 and drug committee in 1963 to promote patient safety. Moreover in 1991, a published study highlighted the risks of error in medical care by reviewing more than 30,000 patient hospital records.[1]

In 1999, the Institute of Medicine published its landmark report, “To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System” which mentioned that up to 98,000 people died in hospitals in the United States of American (USA) each year as a result of medical errors. This report emphasized and planned a strategy for improvement for patient safety.[2]

In 2003, an agency for healthcare research and quality in USA and in 2004, the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) in United Kingdom (UK) established a framework and steps to support patient safety in the practice.[1] The report reflected the actions taken towards reducing harm or risk to the patient in the clinic.

In 1993, the health and safety commission in UK defined safety culture as “The product of individual and group values, attitudes, perceptions, competencies, and patterns of behavior that determine the commitment to, and the style and proficiency of an organization's health and safety management”.[3]

Patient safety is defined as “the avoidance and prevention of patient injuries or adverse events resulting from the processes of health care delivery”.[4] Patient safety is important in the daily practice because it improves quality of care such as leading to the right diagnosis, preventing infections in the hospital, avoiding medication errors, and delivering proper management.[5]

Even though the damage caused to patient by dental staff is less severe than that caused by other medical staff, sometime accidents can occur and may lead to serious complications affecting patient's health. In the dental clinic, dentist and dental assistant handle and inject drugs (e.g., local anesthesia) and use advanced technical devices (e.g., laser, electrocautery, etc).[6] Moreover, dental staff have a direct contact with blood and body fluids of patients which can transmit infectious disease from patient to dental staff and vice versa.[6]

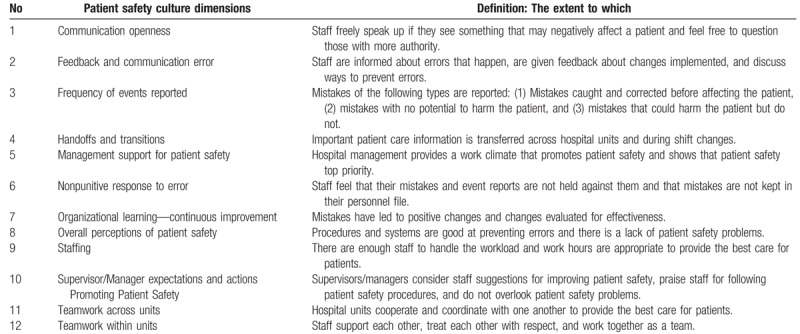

Safety culture is measured by surveys of health providers. A positive safety culture is essential to patient safety. Many tools in the literature have been used to measure patient safety culture. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) developed hospital survey on patient safety culture which is validated and used worldwide. This survey consists of 12 dimensions as shown in Table 1. This survey helps to raises staff awareness, assess the current status, and examine trends in patient safety culture change over time.[4]

Table 1.

Patient safety culture dimensions and definitions[4].

Only a few studies were done that assess patient safety culture in dentistry. The aim of this study was to assess staff and student perceptions of the patient safety culture in the clinics of the College of Dentistry at King Saud University (KSU) in Saudi Arabia.

2. Methods

The current cross-sectional study was conducted in the College of Dentistry at KSU in Saudi Arabia which is the oldest dental college in Saudi Arabia and is established in 1957 as public college, graduates approximately 100 students per year and accommodates approximately 595 students in all levels (300 males and 185 female students). It consists of 500 dental clinics for training.

This study included all 4th and 5th year students, interns, general dental practitioners, and dental assistants in the middle of academic year 2015. Exclusion criteria were all students who did not start clinical training, all faculty, specialist, and consultants.

Research approval was obtained from the College of Dentistry Research Center with registration number: FR 0228 before the start of data collection. The data were collected by using paper-based questionnaire of modified version of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture that utilize a 5-likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

The survey tool was translated to Arabic for staff who are not fluent in English. Some questions were omitted if they were not applicable to the student and assistant experience or if students had minimal exposure to the content of the question.

A pilot test was conducted by distributing the questionnaire to 6 students, 4 interns, 2 specialists, and 4 assistants who had experience in the clinic of the college and were therefore excluded from the study.

Researchers distributed the questionnaire to all sample face to face in the clinics. An introductory first page was attached to the questionnaire explaining the purpose of the study and assuring the confidentiality of the participants’ information. Participation was voluntary, and all responses to the questions were anonymous. Respondents received no financial or other incentives for participating in the survey.

Data were entered into SPSS Version 20. Descriptive statistics (frequency and table) were used to describe the basic features of the data. An overall score for items within dimension was calculated. Score on a particular safety culture dimension was calculated by taking the average percent of the positive responses on all items included in the dimension.

Chi-square test was used to compare percent positive score between areas. P value less than .05 was considered as level of significance.

3. Result

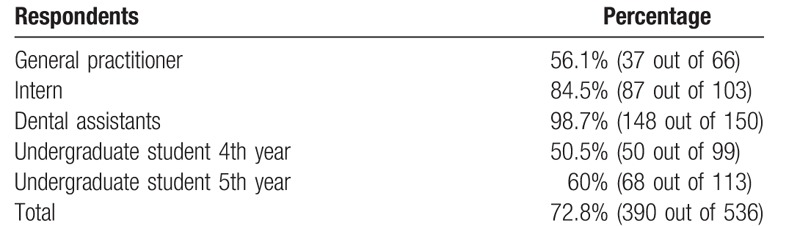

The overall response rate of the survey was 72.8% (390/536). The percentage of the respondents is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Response rate of all respondents.

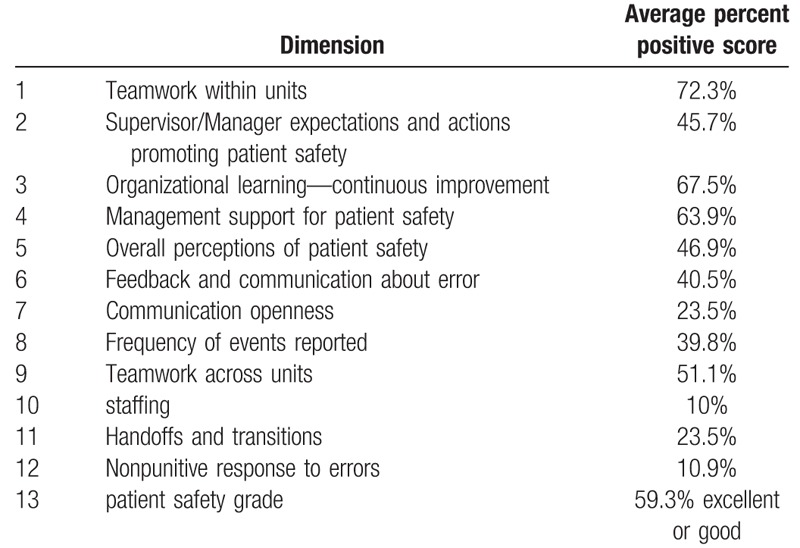

Team work dimension had the highest average percent positive dimension score (72.3%) among all respondents while staffing had the lowest score (10%) as shown in Table 3 which showed the average percent positive dimension score of all the respondents. Table 4 showed the detailed average percent positive dimension score perceptions in all areas.

Table 3.

Average percent positive dimension score of all respondents.

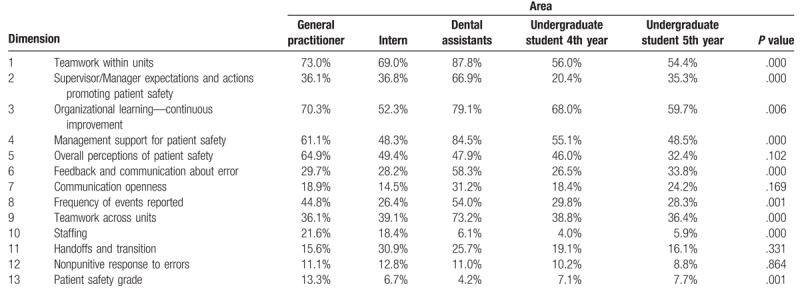

Table 4.

Average percent positive dimension score perceptions of all areas.

There were significant associations between the areas and dimensions. Results showed that in Teamwork dimension, dental assistant had high agreement (87.8%) while 4th and 5th year students had the lowest agreement (56% and 54.4%, respectively, P value: .000); Supervisor/Manager Expectations and Actions Promoting Patient Safety dimension, dental assistant had high agreement (66.9%) while 4th year students had the lowest agreement (20.4%) (P value: .000); Organizational Learning—Continuous Improvement dimension, dental assistant had high agreement (79.1%) while interns had the lowest agreement (52.3%) (P value: .006); Management Support for Patient Safety dimension, dental assistant had high agreement (84.5%) while interns and 5th year students had the lowest agreement (48.3% and 48.5%, respectively) (P value: .000); Feedback and Communication About Error dimension, dental assistant had high agreement (58.3%) while 4th year students had the lowest agreement (26.5%) (P value: .000); Frequency of Events Reported dimension, dental assistant had high agreement (54.0%) while interns had the lowest agreement (26.4%) (P value: .001); Teamwork Across Units dimension, dental assistant had high agreement (73.2%) while general practitioner had the lowest agreement (36.1%) (P value: .000). Staffing dimension, general practitioner had high agreement (21.6%) while 4th year students had the lowest agreement (4.0%) (P value: .000).

In Teamwork dimension, respondents (19.8%) perceived that when 1 area in this unit gets really busy, others help out. In Supervisor/Manager Expectations and Actions Promoting Patient Safety, respondents (33.5%) reported that whenever pressure builds up, their supervisor/manager wants them to work faster, even if it means taking shortcuts. In Organizational Learning—Continuous Improvement, respondents (15.9%) perceived that mistakes have led to positive changes. In Management Support for Patient Safety, respondents (38.9%) reported that clinic management office seems interested in patient safety only after an adverse event happens. In Overall Perceptions of Patient Safety, respondents (48.4%) reported that it is just by chance that more serious mistakes do not happen around here. In Feedback and Communication About Error, respondents (27.8%) felt that they are given feedback about changes put into place based on event reports. In Communication Openness, respondents (49.2%) perceived that staff feel free to question the decisions or actions of those with more authority. In Frequency of Events, respondents (24.3%) reported that rarely or never “mistake is reported” if it is made, but has no potential to harm the patient. In Teamwork Across Units, respondents (26.8%) reported that it is often unpleasant to work with staff from other clinical units. In Staffing respondents, respondents (57.7%) reported that they work in “crisis mode” trying to do too much, too quickly. In Handoffs and Transitions, respondents (41.3%) reported that problems often occur in the exchange of information across clinical units. In Nonpunitive Response to Errors, respondents (69.5%) perceived that staff worry that mistakes they make are kept in their personnel file.

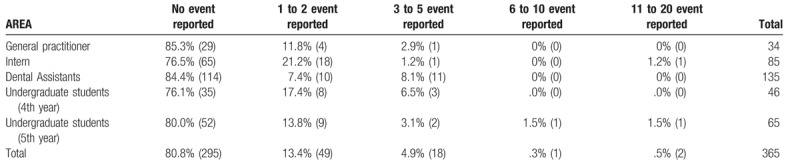

Table 5 showed the number of events reported in the past 12 months. Most of areas perceived that there is no event reported (76.1%–85.3%).

Table 5.

Number of events reported in the past 12 months.

4. Discussion

The current study utilized modified AHRQ questionnaire to assess staff and student perceptions of the patient safety culture in the clinics of the College of Dentistry at KSU after exposing to a variety of settings during their practice. Overall, this study highlights different average percent positive dimension scores of patient safety.

Most notably, Teamwork within Units and Organizational Learning—Continuous Improvement dimension had the highest score which reflects responsibility value toward implementation of patient safety principle in the clinic. The results of current study are similar to other study which found that physicians in department of medicine had high score of teamwork within units.[7]

The results of current study are similar to findings of other studies which are conducted in different hospitals in Riyadh[8–10] and Kuwait.[11] Authors found that the average percent positive dimension score of patient safety is high in Organizational Learning and Continuous Improvement and Teamwork within units while the score is low in Non-punitive Response to Error, Staffing, and Communication Openness.

Many studies revealed that patient safety culture perceptions vary across hospital's units, which is similar to the current study that revealed that there was variation in the perceptions among areas.[12–14]

The results of the current study revealed that dental assistants had higher scores than students in different dimensions. A possible explanation for this finding was that dental assistants are employee, familiar with system and have long experience while students are trainee and are not familiar with the system and focusing in their study and completing their clinical requirements to pass the courses.

The current study found that students in “teamwork within units” and “organizational learning” had slightly higher score among all areas but they were not the highest score. In contrast to the study by Bowman et al[15] on medical students, they found that medical students had the highest score in “teamwork within units” and “organizational learning”. Moreover, current study found that students had the lowest score in “staffing dimension” which was unlike the study of Bowman et al which found that students in “communication openness” and “nonpunitive response to error” had the lowest score.

Many studies noted that “communication openness and punitive response” are strong barriers to student's engagement in patient safety behaviors.[16–18] The present study is in line with Bowman et al[19] who used AHRQ questionnaire, stated that communication openness work as barrier to engage medical students in patient safety. In current study dental students perceived “communication openness” had low percent positive score. This findings is attributed to students are afraid and lack freedom to discuss and speak up if they see negative event that may affect patient care.

Even though students in the current study had low score in “communication openness” and “nonpunitive response to errors” they perceived that they can speak up, ask question, and do not feel that mistakes were held against them which contradicts with a study[15] which stated that medical students perceived that they would not speak up when they see events that may negatively affect patient care and were afraid to ask questions if things did not seem right and feel that mistakes were held against them.

Moreover, the study by Reyna et al[20] on nurses in a nonteaching medicine indicated that nurses felt there is a lack of “communication openness and nonpunitive response to errors” which is similar to findings of current study that revealed that dental assistants had low score in “communication openness and nonpunitive response to errors” dimension.

A study by Abdou et al at the Student University Hospital, Egypt aimed to assess patient safety culture among nurses. The study[21] found that nurses had positive responses of safety culture dimensions with the highest ratings even though their study was in a medical hospital not in a dental clinic and did not use AHRQ questionnaire, their findings is similar to current study findings which revealed that dental assistants had positive response in many patient safety dimensions except “staffing” and “nonpunitive response to errors” which had low percent positive score.

In the literatures, many reasons were explained failing to report error such as reporting error will not generate change, fear and humiliation, and the system's punitive procedural processes.[22]

The presence of enough well-trained staff in the clinic will facilitate providing high quality of health care. Therefore, decreasing the number of staff can cause overwork, stress, burnout, personal accident, and conflict with other staff member which may affect patient safety and lead to medical error.[23]

One of the strengths of this study was its use of the AHRQ Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture, which is the most commonly validated tool used to assess the patient safety culture. This study also utilized the Arabic and English version to facilitate understanding and response to the specific items of the survey.

Some limitations of this study need to be considered when interpreting the results. It was done in 1 College of Dentistry that reflects local condition of staff and student which limit generalizability of the findings in other schools or in other hospital systems. Also, this study was conducted in 1 academic year only which did not reflect how dental staff and students perceive over long time to assess their perceptions of the patient safety culture.

Furthermore, achieving competency in patient safety principles is important for future dental staff (dentist and assistant), which must be fostered by the college's curriculum to establish a positive safety culture.

Well-structured strategies[1] in the clinic are important to create a culture that emphasize and promote an environment to achieve high level quality of patient safety.

5. Conclusions

Overall patient safety grade is more than moderate in the clinic. Teamwork within Units and Organizational Learning—Continuous Improvement dimension had the highest score while staffing had the lowest score. Perception of patient safety culture differs among areas (dental staff, and students). Dental assistants perceived positive score in most dimensions while students perceived slight negative score in most dimensions. Communication Openness, Staffing, and Nonpunitive Response to Errors need more emphasis and strategies by the college to improve patient safety culture in the clinic.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the College of Dentistry Research Center at the King Saud University and Mr. Nassr Al-Maflehi for his guidance in statistical analysis. The authors also wish to thank staff and students for their participation in this study.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AHRQ = Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, KSU = King Saud University, NPSA = National Patient Safety Agency, UK = United Kingdom, USA = United States of American.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Pemberton MN. Developing patient safety in dentistry. Brit Dent J 2014;217:335–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington Metropolitan Area, Institute of Medicine, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Cooper D. Safety culture—a model for understanding and quantifying difficult concept. Prof Saf J 2002;30–6. [Google Scholar]

- [4].AHRQ Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture: User's Guide. In: Services HaH, ed. USA: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016:49. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Important Patient Safety Issues: What You Can Do. 2017. Available at: http://www.npsf.org/?page=safetyissuespatfam&hhSearchTerms=%22%22Important+Patient+Safety%22%22. Accessed February 5, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yamalik N, Perez BP. Patient safety and dentistry: what do we need to know? Fundamentals of patient safety, the safety culture and implementation of patient safety measures in dental practice. Int Dent J 2012;62:189–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kneeland P, Neeman N, Ranji S, et al. Assessing Safety Culture Within an Academic Department of Medicine [abstract]. J Hosp Med 2011;6(suppl 2): http://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/assessing-safety-culture-within-an-academic-department-of-medicine/http://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/assessing-safety-culture-within-an-academic-department-of-medicine/. Accessed December 28, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [8].El-Jardali F, Sheikh F, Garcia NA, et al. Patient safety culture in a large teaching hospital in Riyadh: baseline assessment, comparative analysis and opportunities for improvement. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Al-Ahmadi TA. Measuring patient safety culture in Riyadh's hospitals: a comparison between public and private hospitals. J Egypt Public Health Assoc 2009;84:479–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Alahmadi HA. Assessment of patient safety culture in Saudi Arabian hospitals. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Mohamed GM, Ghani E-rHA, Hanan M, et al. Assessment of patient safety culture in primary health care settings in Kuwait. Epidemiol Biostat Public Health 2014;11:9. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Huang DT, Clermont G, Sexton JB, et al. Perceptions of safety culture vary across the intensive care units of a single institution. Crit Care Med 2007;35:165–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kaafarani HM, Itani KM, Rosen AK, et al. How does patient safety culture in the operating room and post-anesthesia care unit compare to the rest of the hospital? Am J Surg 2009;198:70–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Singer SJ, Gaba DM, Falwell A, et al. Patient safety climate in 92 US hospitals: differences by work area and discipline. Med Care 2009;47:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bowman C, Neeman N, Sehgal NL. Enculturation of unsafe attitudes and behaviors: student perceptions of safety culture. Acad Med 2013;88:802–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wetzel AP, Dow AW, Mazmanian PE. Patient safety attitudes and behaviors of graduating medical students. Eval Health Prof 2012;35:221–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Caldicott CV, Faber-Langendoen K. Deception, discrimination, and fear of reprisal: lessons in ethics from third-year medical students. Acad Med 2005;80:866–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Vohra PD, Johnson JK, Daugherty CK, et al. Housestaff and medical student attitudes toward medical errors and adverse events. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2007;33:493–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bowman C, Neeman N, Seghal N. Assessing student perceptions of safety culture during internal medicine and surgery clerkships. J Hosp Med 2012;7(suppl 2):68. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Samra HA, McGrath JM, Rollins W. Patient safety in the NICU: a comprehensive review. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs 2011;25:123–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Abdou HA, Saber KM. A baseline assessment of patient safety culture among nurses at Student University Hospital World. J Med Sci 2011;6:17–26. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jonathan B Vangeest, Deborah S Cummins. An Educational Needs Assessment for Improving Patient Safety Results of a National Study of Physicians and Nurses. National Patient Safety Foundation, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Baldwin DC, Jr, Daugherty SR, Tsai R, et al. A national survey of residents’ self-reported work hours: thinking beyond specialty. Acad Med 2003;78:1154–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]