Abstract

Background

The BES1 gene family, an important class of plant-specific transcription factors, play key roles in the BR signal pathway in plants, regulating various development processes. Until now, there has been no comprehensive analysis of the BES1 gene family in Brassica napus, and a cross-genome exploration of their origin, copy number changes, and functional innovation in plants was also not available.

Results

We identified 28 BES1 genes in B. napus from its two subgenomes (AA and CC). We found that 71.43% of them were duplicated in the tetraploidization, and their gene expression showed a prominent subgenome bias in the roots. Additionally, we identified 104 BES1 genes in another 18 representative angiosperms and performed a comparative analysis with B. napus, including evolutionary trajectory, gene duplication, positive selection, and expression pattern. Exploiting the available genome datasets, we performed a large-scale analysis across plants and algae suggested that the BES1 gene family could have originated from group F, expanding to form other groups (A to E) by duplicating or alternatively deleting some domains. We detected an additional domain containing M4 to M8 in exclusively groups F1 and F2. We found evidence that whole-genome duplication (WGD) contributed the most to the expansion of this gene family among examined dicots, while dispersed duplication contributed the most to expansion in certain monocots. Moreover, we inferred that positive selection might have occurred on major phylogenetic nodes during the evolution of plants.

Conclusions

Grossly, a cross-genome comparative analysis of the BES1 genes in B. napus and other species sheds light on understanding its copy number expansion, natural selection, and functional innovation.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12864-018-4744-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: BES1 gene family, Evolutionary trajectory, Polyploid, Positive selection, Expression pattern, B. napus

Background

Plants often suffer a series of biotic and abiotic stresses, causing a decrease in yield and quality. Transcription factors, which can bind to specific sequences, play important and critical roles in plant growth and resistance to various stresses [1]. The BES1 (BRI1-EMS-SUPPRESSOR1) gene family is a novel class of plant-specific transcription factors that regulate BR-responsive genes [2]. Brassinosteroids (BRs) are a class of plant steroid hormones that regulate various development processes, such as leaf development, stem elongation, pollen tube growth, xylem cell differentiation, senescence, and photomorphogenesis [3–5]. Plants are often protected by BRs from all kinds of environmental stresses, including low- and high-temperatures, salinity, drought, injury, pathogens, and insect attack [6–9].

The BES1 gene family plays key roles in the BR signalling pathway. BES1 binds to the promoter region of SAUR-AC1, which has become a molecular tool to dissect brassinosteroid and auxin responses [2, 10]. In addition, BES1 interacts with a bHLH protein BIM1 (BES1-interacting Myc-like1) to synergistically bind to E-box sequences that are present in many BR-induced gene promoters [2, 11]. In A. thaliana, several members of the BES1 gene family have been identified, such as BES1, BZR1, and BEH1–4. These transcription factors have a gene function that is redundant in the BR signalling pathway [2]. The BES1 genes contain an NLS (Nuclear localization signal), followed by a highly conserved amino-terminal domain (N), phosphorylation domain (P), a PEST motif, and a carboxyl-terminal domain (C). The central P domain of BES1 genes is the target of BIN2 kinase, and the PEST motif is implicated in protein degradation [2, 12].

There are few prior studies on the evolution of the BES1 gene family. Recent studies have found that the BES1 locus in A. thaliana encodes two isoforms, long and short BES1 (BES1-L and BES1-S). Among them, BES1-L has an additional 22 amino acids in the N terminal, and it has a stronger biological function than BES1-S. It can promote the nuclear localization of BZR1 and BES1-S [13]. BES1-L is an important isoform in the BR signalling pathway, and it uniquely exists in the majority of A. thaliana ecotypes. BES1-L is a more recently evolved isoform and may have contributed to the expansion and evolution of A. thaliana [13]. BES1 shows relaxed selection compared to BZR1, hallmark of sub- and neofunctionalization, and dynamic HSP90 client status across independent evolutionary paths [14]. By ChIP-chip and gene expression analyses, a comprehensive transcriptional network for BES1-regulated genes was constructed, which contained 1609 putative BES1 target genes [15]. For a member of the BES1 gene family, the phylogenetic tree indicates that angiosperm BZR1-like genes form two groups, BZR1 and BZR2/3/4. However, only one BZR1-like gene was detected in the basal extant angiosperm (A. trichopoda). These two groups may be generated by a gene duplication event before the diversification of extant angiosperms, while A. trichopoda lost the BZR1 member during its evolution [16]. Previously, we also conducted a genome-wide analysis of the BES1 gene family in Chinese cabbage, and explored its structural and functional changes in the process of evolution [17].

In that it is pivotal in its importance to plant growth, the BES1 gene family has been identified and analysed in some plants, including A. thaliana [2], O. sativa [18], and B. rapa [17]. However, in B. napus, there is a lack of studies on the function and structure of the evolution of the BES1 gene family. B. napus is an important oilseed crop grown worldwide as a member of the genus Brassica. B. napus (AACC genome), an allopolyploid, originated from hybridization of B. rapa (AA genome) and B. oleracea (CC genome) [19]. The availability of these Brassica genomes, together with those of a model species, provided an opportunity to understand the formation and evolution of the BES1 gene family.

The aims of this study were to: (i) identify and characterize the BES1 gene family in B. napus and 18 other species to understand their evolutionary pattern across plant species; (ii) to characterize their phylogenetic relationships, origin and evolution, and infer duplicated genes; (iii) by inferring gene collinearity, to find how polyploidization has contributed to the evolution of this gene family; and (iv) to explore expression patterns of BES1 genes in two tissues based on the transcriptome and microarray data. This comprehensive analyses contributes to our understanding of the functional innovation of this important gene family, as well as the effect of gene loss, retention, and expansion, especially due to recursive polyploidization.

Methods

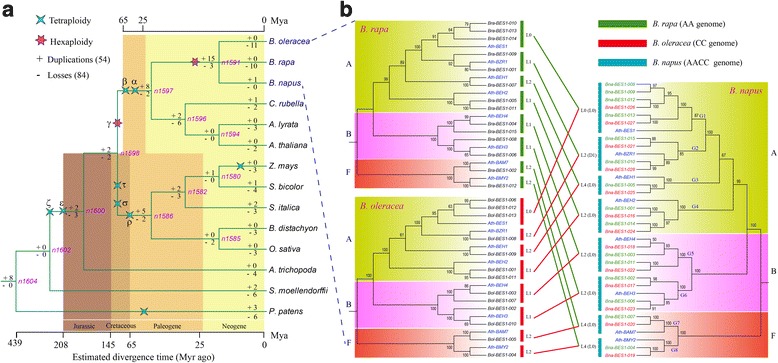

Retrieval of genome sequences

The B. napus and 18 representative genome sequences were used for comparative analyses. These species contained 6 dicots, 5 monocots, 1 basal angiosperm, 1 Pteridophyta, 1 Bryophyta, and 5 green algae (Fig. 1). The genome sequences of B. napus were downloaded from the Genoscope genome database [19]. The A. thaliana sequences were downloaded from TAIR, and the rice sequences were downloaded from RGAP [20]. The B. rapa sequences were from BRAD [21] and the B. oleracea sequences were from EMBL (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/). The A. trichopoda sequences were downloaded from the Amborella Genome Database [22]. The sequences of the other species were downloaded from phytozome [23].

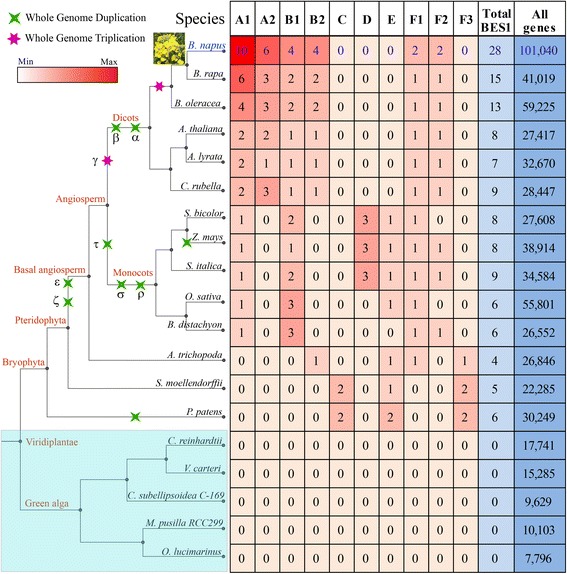

Fig. 1.

The number and classification of BES1 genes in B. napus and the other 18 species used in this study. Information regarding genome duplication was obtained from the Plant Genome Duplication Database (PGDD)

Identification and characterization of the BES1 gene family.

The Pfam database (version 31.0) was used to identify BES1 genes from all protein sequences with a threshold of e-value <1e-5 [24]. BES1 genes have the typical BES1_N domain (PF05687.9). The retrieved BES1 candidates were further verified by using the SMART and Conserved Domain Database with default parameters [25, 26]. To eliminate possible pseudogenes, sequences with < 150 amino acids were removed for further analysis. MEME (version 4.12.0) was used to search for conserved motifs, and the number of motifs was set as 10 [27]. The protein structure was predicted using the Swiss-model database [28]. The interaction networks of A. thaliana BES1 genes were constructed using the STRING database (http://string-db.org). The RNA-seq data was used to analyse BES1 gene expression in leaves and roots in B. napus [19]. This dataset contained three replicates, and the RPKM value was log10 transformed. Expression data of A. thaliana genes were obtained from the BAR database (http://bar.utoronto.ca/) [29, 30]. The expression analysis of BES1 genes under heat, cold and salt treatments by qRT-PCR was conducted according to our previously reported methods [31, 32].

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analyses

Multiple sequence alignment was performed using MUSCLE with default parameters [33]. Based on alignment, we generated a phylogeny using previously reported methods [34]. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted using three methods: Neighbour-joining (NJ), Maximum Likelihood (ML), and Bayesian. NJ trees were constructed using MEGA 6.0 with 1000 bootstrap and a Poisson correction model [35]. The MrBayes v3.2.6 software was employed to construct Bayesian trees using the fixed (Jones) model for amino acid substitutions that was run for 4 × 106 generations, with 6 Markov chains, sampled every 1 × 104 generations [36]. PhyML 3.0 was employed to construct ML trees, with the Jones, Taylor and Thorton (JTT) model, and 100 nonparametric bootstrap replicates [37]. The reconstructed BES1 gene trees were compared with real species trees by lineage using Notung 2.9 software with default parameters [38].

Orthologs, paralogs, duplicated type, and collinear blocks identification

Orthologous and paralogous BES1 genes were identified using OrthoMCl (v2.0, e-value: 1e-5), and then we counted the orthologous gene pairs for each A. thaliana BES1 gene manually [39]. Their relationships were constructed using Cytoscape (v3.6.0) [40]. First, whole-genome protein sequences from all species were searched against themselves using BLASTP with an E-value of 1 × 10− 5. MCScanX v1.0 (−k 50, −s 5, −m 25) was then used to detect the duplicated type and collinear blocks according to a previous report [41]. Then, we extracted the BES1 genes located in the collinear blocks by Perl scripts.

Selective pressure detection in each group

To estimate the divergence time between collinear BES1 gene pairs, alignment of protein sequences was performed using ClustalW2.0, and then translated into CDS alignment. We applied likelihood ratio tests of positive selection based on ML methods and codon substitution models. Based on reported methods [42, 43], to find evolutionary traces of selective pressures, we analysed each group to infer ω (the ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous distances) using Codeml implemented from PAML4.9 [44, 45]. We employed a complete deletion method when analysing alignments with gaps, and eliminated sequences that contained 40% of their length or more as InDels. We detected variation in ω among sites by employing a likelihood ratio test between the M0 and M1 and M7 and M8 models.

Results

Identification and characterization of the BES1 gene family

We systematically identified BES1 genes by searching Pfam database in B. napus and 18 other representative species, including 5 dicots (B. rapa, B. oleracea, A. thaliana, A. lyrata, and C. rubella), 5 monocots (S. bicolor, Z. mays, S. italica, O. sativa, and B. distachyon), 1 basal angiosperm (A. trichopoda), 1 Pteridophyta (S. moellendorffii), 1 Bryophyta (P. patens), and 5 green algae species (Fig. 1). After filters, a total of 132 BES1 genes were identified among all species. Allotetraploid plant B. napus contained the most BES1 genes (28), being just the addition of its two diploid progenitors B. rapa (15) and B. oleracea (13) (Fig. 1). Generally, there were more BES1 genes in diploid Brassica genomes than others due to their shared genome duplication event. No BES1 gene was identified in the five green algae species. This result indicated that the BES1 genes were subjected to large-scale expansion in higher plants.

Phylogenetic and classification analysis of BES1 genes

To conduct the classification of BES1 genes, we constructed a phylogenetic tree using all of the examined species by MEGA 6.0. The 132 BES1 genes of the 14 species were clearly grouped into six groups (A to F) according to the bootstrap values and phylogenetic topology (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, groups A and B were divided into 2 distinct subgroups (A1 and A2, B1 and B2), respectively. The group F was further divided into 3 subgroups corresponding to F1 to F3. In P. patens and S. moellendorffii, all BES1 genes were assigned into C, E, and F3 groups (Figs 1, 2a). However, there was no BES1 gene detected in group C among the angiosperm species, indicating that the genes of group C might have experienced an evolutionary divergence in structure or function.

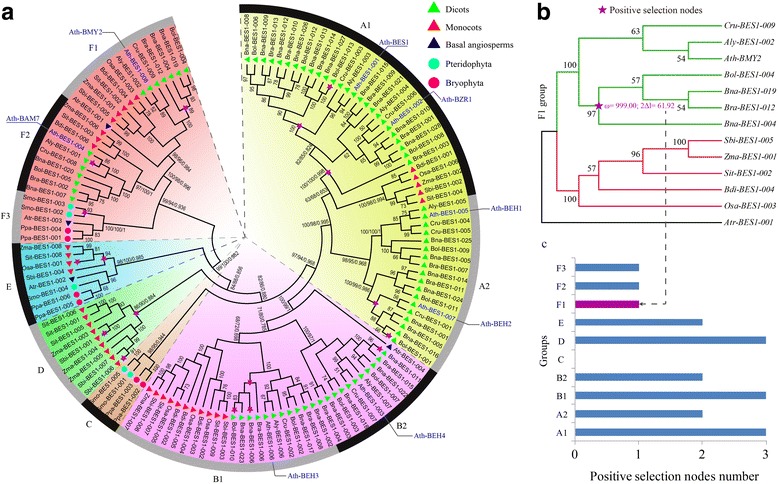

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic relationship and positive selection analyses of the BES1 gene family. a Phylogenetic tree topology was generated via MEGA6.0. For the major nodes, neighbour-joining (NJ) and maximum-likelihood (ML) bootstrap values above 50% are shown, followed by Bayesian posterior probability values (> 0.6) by MrBayes. The A to F indicate the groups obtained by the bootstrap values and phylogenetic topology. b Positive selection analyses of groups F1 in representative species. The ω on the clades is the dn/ds value under the M8 model of codeml. c The positive selection nodes number in each group in the representative species

Among B. napus and other 5 dicots, we found that more than 70% of genes belonged to groups A and B, and there was no BES1 gene in groups C, D, E, and F3 (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the results showed that the expansion of BES1 genes in 3 Brassica species mainly occurred in groups A and B due to their genome duplication events. In the 5 monocots species, there was no gene in groups A2, B2, C, and F3 (Fig. 1). Interestingly, we found that groups D and E contained BES1 genes in most of the monocots but not in the dicots. In addition, we noted that S. bicolor, Z. mays, and S. italica contained 3 genes in group D, while there was no gene in this group for O. sativa and B. distachyon. These results indicated that there have been lineage-specific expansion of BES1 genes after the divergence of dicots and monocots.

Positive selection analyses for the BES1 gene family

Strong positive selection was observed for the major nodes on the phylogenetic tree, which possibly contributed to the divergence of higher plants. To uncover whether and when natural selection had acted on the evolution of the BES1 gene family, we performed selection pressure analyses in each group using PAML program. Taking the F1 group as an example, 1 significantly nonsynonymous vs synonymous substitution (ω = 999.00, 2Δl = 61.92) was detected, showing a strong positive selection after the divergence of Brassica and other species (Fig. 2b). This branch contained 4 Brassica genes, such as Bol-BES1–004, Bna-BES1–019, Bra-BES1–012, and Bna-BES1–004.

Furthermore, we also detected positive selection for other groups (Additional file 1: Figure S1). The results showed that there were more positive selection nodes in groups A1, B1, and D than in the other groups, and the number reached 3 (Fig. 2c). In groups A2, B2, and E, 2 positive selection nodes were detected, and there was no positive selection node in group C. Generally, we found there were more positive selection nodes in dicots (12, groups A, B, F1, and F2), followed by monocots (5, groups D and E). This result indicated that BES1 genes in dicots underwent more positive selection than those in other lineages.

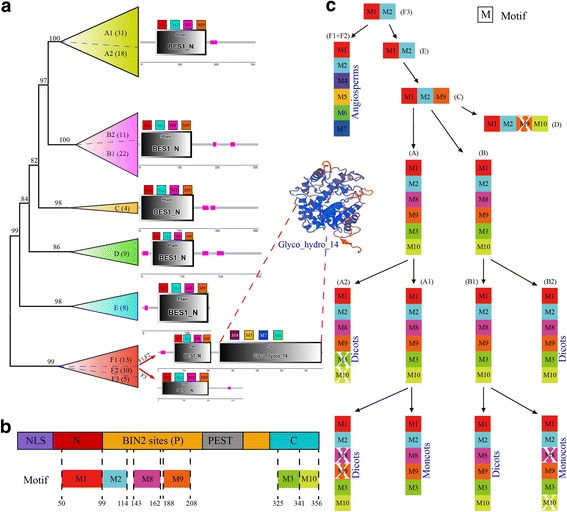

Conserved motif analysis of BES1 genes exploring their origin and evolutionary pattern

To further explore the origin and evolutionary pattern of BES1 genes, the most conserved 10 motifs (M) were detected by MEME program (Fig. 3a, Additional file 2: Figure S2). The M1 was located at the amino-terminal domain (N), and M2, M8, and M9 constituted BIN2 phosphorylation sites (P), and M3, M10 belonged to the carboxyl domain (C) (Fig. 3b). All genes had M1 and M2, while the other 8 motifs existed in some but not all groups (Additional file 2: Figure S3).

Fig. 3.

The converted motif and evolutionary trajectories analyses of the BES1 gene family in plants. a The motif 1 to motif 10 (M1 to M10) of the BES1 gene family for each group. b The correspondence relationship between schematic structures of BES1 and motifs. c The major evolutionary trajectories of the BES1 gene family. The white X indicated the motif was lost in some genes

We found specific preservation and expansion of motifs in different plant lineages (Fig. 3c). Among F subgroups, F3 contained 5 genes, including 2 P. patens, 2 S. moellendorffii, and 1 A. trichopoda genes, while subgroups F1 and F2 only contained angiosperm genes. Interestingly, we found subgroups F1 and F2 contained M4 to M7, which were absent in F3 and other groups. For group E, only M1 and M2 were detected, and this group did not contain dicot genes. For group C, M1, M2, and M9 were identified, which only contained 2 P. patens, and 2 S. moellendorffii genes. Group D was specific for monocots, and contained M1, M2, M9, and M10, while M9 might have lost some genes. Two main groups, A and B, existed in most angiosperm species. Most genes in these two groups contained M1, M2, M8, M9, M3, and M10.

For genes in groups F1 and F2, we detected an additional domain, glyco_hydro_14, being contained in M4 to M8 (Additional file 2: Figure S3). To explore the sequence divergence of BES1 genes among F1, F2 and F3, we conducted sequence alignments using all genes belonging to the F group (Additional file 2: Figure S4). The results showed that the first 70 amino acids of the BES1_N domain were very conserved among the three subgroups. We found 12, 36, 40, and 45 amino acids in the BES1_N domain were the same in the F1 and F2 subgroups, which were different from the F3 subgroup. For the Glyco_hydro_14 domain, we found that it was conserved between the F1 and F2 subgroups, while it was divergent or had lost parts in the F3 subgroup (Additional file 2: Figure S4). We further conducted protein structure analyses using the Swiss-model database. We found that its homology model was 1fa2.1.A, with a similarity of up to 46.59% (Additional file 2: Figure S5a). Further assessment also showed that this predicted model had high quality and accuracy (Additional file 2: Figure S5b–d).

Identification of orthologous and paralogous BES1 genes between B. napus and other species.

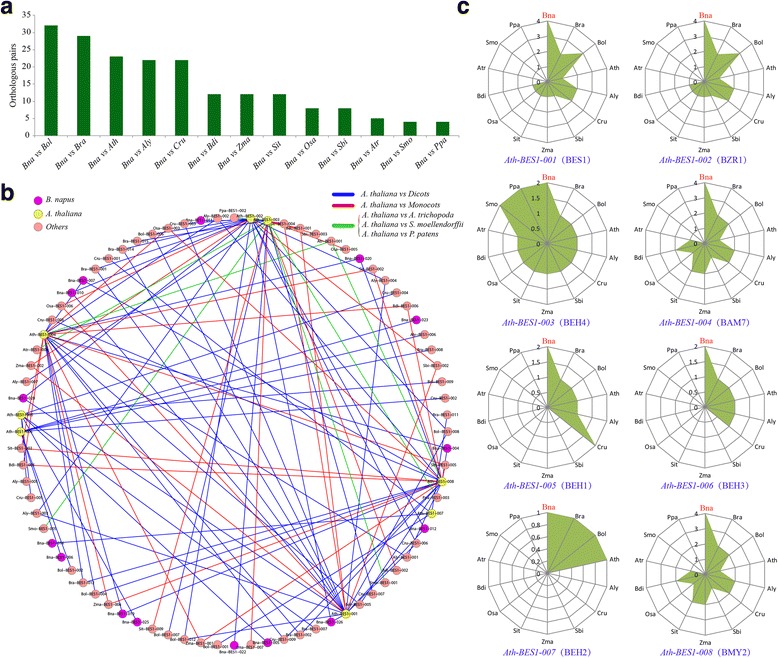

We identified orthologous gene pairs between B. napus, A. thaliana, O. sativa, A. trichopoda, S. moellendorffii, P. patens and other species, respectively using the OrthoMCL program (Additional file 3: Table S1). There were more orthologous pairs between B. napus and B. oleracea (32), followed by B. rapa (29) and A. thaliana (23) (Fig. 4a). Taking the orthologous genes between A. thaliana and other species as an example, we constructed an interaction network (Fig. 4b). There were more orthologous gene pairs for Ath-BES1, Ath-BZR1, Ath-BAM7, Ath-BEH3, and Ath-BMY2 in A. thaliana versus B. napus than versus others (Fig. 4c). For Ath-BEH2, only one orthologous gene pair was identified for A. thaliana versus each Brassica species, while there was no orthologous gene between A. thaliana and others. In O. sativa, there were more orthologous genes between O. sativa and monocots than other comparisons (Additional file 2: Figure S6a). For Osa-BES1–003, 4 orthologous gene pairs were detected between O. sativa and B. napus, which was more than for other comparisons (Additional file 2: Figure S6b). Furthermore, orthologous gene pairs were also detected between A. trichopoda, S. moellendorffii, P. patens, and other species (Additional file 2: Figure S7–9).

Fig. 4.

The analyses of orthologous BES1 genes across species. a The orthologous BES1 gene pairs between B. napus and other examined species. a The interaction network constructed using the orthologous gene pairs between A. thaliana and other species. b The number of orthologous genes in each species with 8 A. thaliana BES1 genes. The abbreviations represent the species as follows: Bna, B. napus; Bra, B. rapa; Bol, B. oleracea; Ath, A. thaliana; Aly, A. lyrata; Cru, C. rubella; Sbi, S. bicolor; Zma, Z. mays; Sit, S. italica; Osa, O. sativa; Bdi, B. distachyon; Atr, A. trichopoda; Smo, S. moellendorffii; Ppa, P. patens

Whole-genome duplication (WGD) may have contributed to the expansion of the gene family. Additionally, 15 paralogous BES1 gene pairs were identified in B. napus, which was far more than in A. thaliana and other plants (Additional file 2: Figure S10, Additional file 3: Additional file 3: Table S2). This might be a result of additional WGDs after its split from A. thaliana. In addition, we found that 4 BES1 genes in B. napus had more than 1 paralogous gene, including Bna-BES1–007, Bna-BES1–004, Bna-BES1–019, and Bna-BES1–020 (Additional file 3: Figure S10). In A. trichopoda, there were no paralogous BES1 genes. Therefore, the number of paralogous information could partly reflect species genome duplication.

Duplicated type identification and synteny analyses of B. napus and other species

Various gene duplications may have contributed to the expansion of the gene family. We found evidence that WGD likely contributed the most to the expansion of this gene family in many plant lineages. We examined 5 types of gene duplications: singleton, dispersed, proximal, tandem, and WGD or segmental duplication by MCScanX program (Table 1, Additional file 3: Table S3). The percentage of WGD was 75.0% in B. napus, B. rapa (80.0%), B. oleracea (84.6%), and A. thaliana (62.5%) (Table 1). However, WGD or segmental duplication contributed the most to gene expansion only in O. sativa (50.0%) and B. distachyon (66.7%). In the other three monocots, the dispersed duplication contributed the most to gene expansion. For A. trichopoda and S. moellendorffii, all BES1 genes belonged to the dispersed duplication. Actually, by checking gene collinearity within a genome, we found that more than 55.0% of BES1 genes in B. napus and the other 5 dicots were located in collinear blocks, showing their duplication during polyploidization (Additional file 3: Table S4). Especially for the 3 Brassica species, more than 75% of BES1 genes were located in collinear blocks. A percentage of 37.5, 37.5, and 33.3% of BES1 genes were located in collinear blocks for S. bicolor, Z. mays, and S. italica, respectively. Furthermore, we found that the percentage of BES1 genes located in the collinear blocks was larger than the average genome-wide level for all examined species except A. trichopoda and S. moellendorffii (Additional file 3: Table S4). The percentage for BES1 genes in colinearity was significantly larger than the average genome-wide level by χ2 test, and P-values were 6.69E-18 and 1.21E-17 for dicots and monocots, respectively.

Table 1.

The identification of duplicated type for BES1 genes and all genes in B. napus and other representative species

| Species | Singleton | Dispersed | Proximal | Tandem | WGD or segmental | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome | BES1 | Genome | BES1 | Genome | BES1 | Genome | BES1 | Genome | BES1 | Genome | BES1 | |

| B. napus | 7768 | 0 | 26,907 | 7 | 2428 | 0 | 2708 | 0 | 61,229 | 21 | 101,040 | 28 |

| B. rapa | 3666 | 0 | 10,622 | 3 | 873 | 0 | 2369 | 0 | 23,489 | 12 | 41,019 | 15 |

| B. oleracea | 4807 | 0 | 25,232 | 2 | 2515 | 0 | 2523 | 0 | 24,148 | 11 | 59,225 | 13 |

| A. thaliana | 5156 | 0 | 10,670 | 3 | 1046 | 0 | 3026 | 0 | 7519 | 5 | 27,417 | 8 |

| A. lyrata | 5585 | 0 | 14,735 | 3 | 1936 | 0 | 3037 | 0 | 7376 | 4 | 32,670 | 7 |

| C. rubella | 3792 | 0 | 10,428 | 3 | 1144 | 0 | 6142 | 1 | 6941 | 5 | 28,447 | 9 |

| S. bicolor | 4756 | 0 | 12,434 | 4 | 1295 | 1 | 3684 | 0 | 5439 | 3 | 27,608 | 8 |

| Z. mays | 7468 | 1 | 16,126 | 4 | 1427 | 0 | 2182 | 0 | 11,711 | 3 | 38,914 | 8 |

| S. italica | 7408 | 0 | 14,785 | 4 | 2183 | 0 | 4365 | 2 | 5843 | 3 | 34,584 | 9 |

| O. sativa | 12,368 | 1 | 30,411 | 2 | 3761 | 0 | 3533 | 0 | 5728 | 3 | 55,801 | 6 |

| B. distachyon | 4857 | 0 | 12,877 | 2 | 1280 | 0 | 2822 | 0 | 4716 | 4 | 26,552 | 6 |

| A. trichopoda | 8608 | 0 | 13,985 | 4 | 1849 | 0 | 2195 | 0 | 209 | 0 | 26,846 | 4 |

| S. moellendorffii | 4164 | 0 | 10,621 | 5 | 2094 | 0 | 1143 | 0 | 4263 | 0 | 22,285 | 5 |

| P. patens | 9966 | 0 | 14,241 | 4 | 1083 | 0 | 979 | 0 | 3980 | 2 | 30,249 | 6 |

Differential BES1 gene losses and duplications during evolution

Expansion of BES1 genes in WGDs was also accompanied by gene losses. To clarify the evolution of the BES1 gene family, we conducted the gene loss and duplication analyses using Notung [46]. We obtained the number variations of BES1 genes at different stages of evolution according to the reconstructed phylogenies (Fig. 5a, Additional file 2: Figure S11). In the lineage leading to the common ancestor of P. patens, S. moellendorffii, and angiosperms, 8 ancestral genes were duplicated, which occurred 439 Mya, while no gene was lost. In the lineage of the common ancestor for A. trichopoda and angiosperms, 2 ancestral genes were duplicated, and 3 genes were lost, which occurred during the Jurassic period. In the lineage leading to the common ancestor of dicots and monocots, 2 ancestral BES1 genes were duplicated and lost, respectively (Fig. 5a). For the branch of the common ancestor of B. napus and 5 dicots, 8 ancestral genes were duplicated, and 2 genes were lost. Since the divergence, the A. thaliana lineage lost 2 genes and there were no duplications. For 3 Brassica species, 15 ancestral genes were duplicated, and 3 genes were lost in the branch of their common ancestor. The B. oleracea and B. rapa lineage lost 11 and 10 genes, respectively, and no duplicated genes were detected. However, the B. napus lineage had no gene losses, and only 1 duplicated gene was detected.

Fig. 5.

The duplication or losses analyses of BES1 genes. a Number variations of BES1 genes at different stages of plant evolution. Differential gene losses and gains are indicated by numbers with - or + on each branch. WGD events are indicated with a quadrilateral or hexagon, respectively. b The duplication or losses analyses of BES1 genes in A. thaliana and 3 Brassica species

For the 5 monocots, 5 ancestral BES1 genes were duplicated, and 2 genes were lost in their lineage of the common ancestor (Fig. 5a). In the common ancestor of O. sativa and B. distachyon, 2 ancestral genes were lost, and no ancestral gene was duplicated. Since the divergence, each of the B. distachyon and O. sativa lineages lost 3 genes, and there was no duplicated gene. In the common ancestor of Z. mays, S. bicolor, and S. italica, 3 ancestral genes were lost, and 2 ancestral genes were duplicated. In conclusion, there were more BES1 gene losses than duplications. The ratio of losses and duplications was 28 versus 2 in dicots, and this ratio was 16 versus 3 in monocots. These results will help us to understand the loss, retention and expansion of this gene family during the evolution of different species.

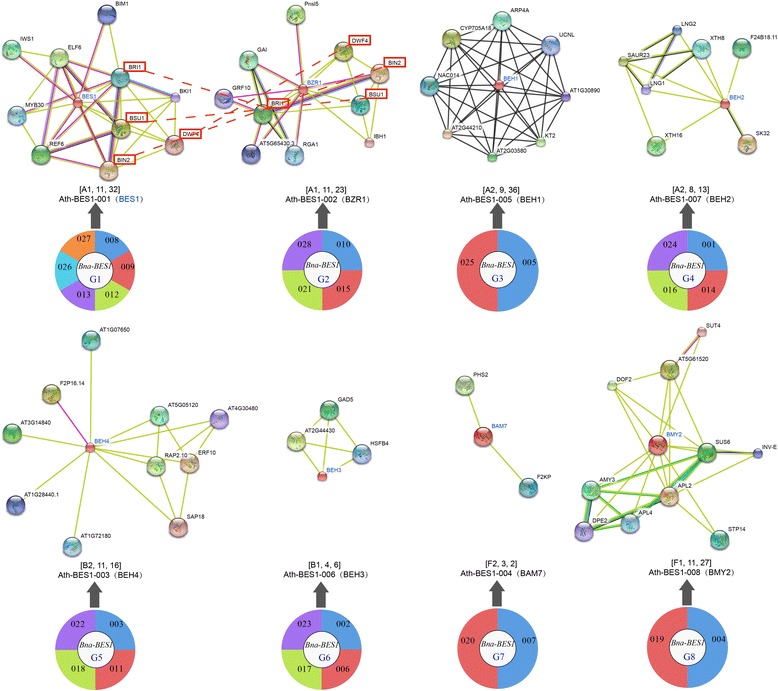

Exploring BES1 gene function in B. napus by comparing it with A. thaliana

A comparison of sequence homologs between non-model and model species might aid in understanding the function of these BES1 genes in non-model species. Taking 3 Brassica species as an example, we constructed three phylogenetic trees for these species and A. thaliana. On the phylogenetic tree, 8 groups (G1 to G8) were obtained according to the BES1 genes of A. thaliana (Fig. 5b). There was no gene loss in G1, while there were 2 or 4 gene losses in the other 7 groups. The BES1 genes within the same taxonomic group with A. thaliana might have similar functions. Therefore, we conducted comprehensive analyses to further explore the function of BES1 genes. First, we constructed interaction networks between each BES1 gene and their corresponding target genes to uncover their regulatory pathways (Fig. 6, Additional file 3: Tables S5, S6). Most target genes were identified in the networks of Ath-BES1, Ath-ZR1, Ath-BEH4, and Ath-BMY2, and the number of target genes achieved 10. Among all eight groups, there were the most B. napus genes involved in Ath-BES1 networks. Interestingly, we identified 4 target genes (BRI1, BSU1, BIN2, and DWF4), which were involved in BES1 and BZR1 networks (Fig. 6). Furthermore, we conducted enrichment analyses for the genes involved in these networks, and found that most genes responded to the brassinosteroid signalling pathway (Additional file 3: Table S7).

Fig. 6.

The construction of interaction networks for each BES1 gene and their target genes in A. thaliana. The pie graph indicates the B. napus BES1 genes involved in the related network of A. thaliana. The three numbers in the bracket indicate the groups, the gene number, and the connection edges

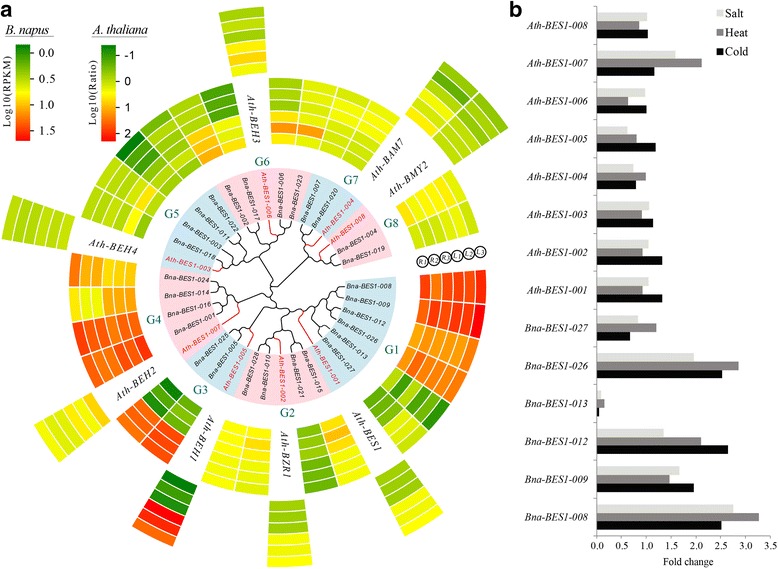

Comparative expression pattern analysis of BES1 genes between A. thaliana and B. napus

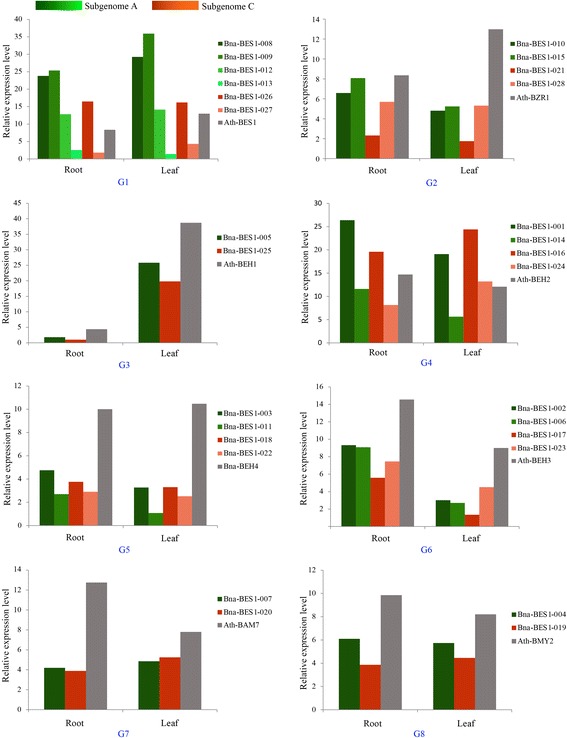

To detect the functional divergence of BES1 genes, their expression was compared in different tissues, i.e., roots and leaves, between A. thaliana (Additional file 3: Table S8) and B. napus (Fig. 7, Additional file 3: Table S9). The results showed that Ath-BEH1 had high expression (log2 (ratio) > 1.5) in leaves, whereas it showed low expression in roots. Four genes (Ath-BEH4, Ath-BEH3, Ath-BAM7, Ath-BMY2) were expressed at low levels in leaves (log2 (ratio) < 0). In roots, 3 of 8 genes showed high expression, including Ath-BAM7, Ath-BEH3, and Ath-BEH2. For B. napus, we found that several genes showed high expression in both leaves and roots, such as all 4 genes in group 4 (G4) and four genes in G1 (Bna-BES1–008,009,012, 026). Interestingly, we found there was similar expression of these genes in the same group between A. thaliana and B. napus. For example, the expression of Bna-BES1–005, and Bna-BES1–025 (G3) had similar patterns to Ath-BEH1 in both roots and leaves. However, Bna-BES1–028 and Bna-BES1–010 were also located in G3, but their expression pattern was significantly different from Ath-BEH1 (Fig. 7a). This might be due to the possibility of subfunctionalization or neofunctionalization after the divergence of A. thaliana and B. napus. In addition, we also found that the expression level of almost all genes in subgenome A was higher than that of subgenome C in roots (Fig. 8, Additional file 2: Figure S12).

Fig. 7.

Expression pattern analysis of BES1 genes in A. thaliana and B. napus. a Phylogenetic relationships were constructed and were divided into 8 groups (G1 to G8) according to the A. thaliana BES1 genes. The genes of A. thaliana, subgenome A, and subgenome C of B. napus are marked with blue, green, and red, respectively. The gene expression in roots (R1, R2, and R3) and leaves (L1, L2, and L3) were determined by the AtGenExpress Visualization Tool and B. napus RNA-Seq. b The expression level of BES1 genes in B. napus and A. thaliana under cold, heat, and salt treatments

Fig. 8.

The histogram of BES1 gene expression in roots and leaves of B. napus and A. thaliana. The G1 to G8 represent the 8 groups classified by A. thaliana BES1 genes. The genes marked with green locate the subgenome A, and red locates the subgenome C of B. napus

Furthermore, we collected and analysed the expression of BES1 genes in model species, which could be helpful for our understanding of homologous gene function in non-model species. Take the BES1 gene as an example, we investigated its expression pattern in A. thaliana under different stresses, such as cold, heat, and salt (Fig. 7b). To explore the expression pattern of the duplicated genes, we conducted the qRT-PCR analyses for BES1 genes in B. napus under cold, heat, and salt treatments. Among the G1 group, there were 6 duplicated genes in B. napus with the A. thaliana BES1 gene. The results showed that Bna-BES1–013 had a relatively low expression (Fig. 7b). This indicates that not all duplicated genes are highly expressed, and some genes may be de-functionalized after duplication.

Discussion

Origination, evolution and expansion of BES1 family genes

The evolution and origin of BES1 genes in representative plants were analysed, and their evolutionary pattern was determined using phylogenetic and conversed motif analyses. As to our phylogenetic analysis, BES1 family genes may have first originated from the group F3, which contains only the M1 and M2 motifs. Then, it developed novel genes through acquiring other motifs, such as M2 to M10. Furthermore, several specific groups or subgroups were obtained for dicot and monocot species. In groups F1 and F2, we detected an additional domain contained M4 to M8, which did not exist in the other groups. The WGD or segmental duplication contributed the most to the expansion of this gene family among all 6 dicots [47, 48]. However, the dispersed duplication contributed the most to its expansion in 3 monocots. The percentage of BES1 genes located in collinear blocks was significant larger than the average genome-wide level for nearly all examined species.

The Brassica genome has undergone genome duplication events since its divergence from A. thaliana [47, 49–51]. Furthermore, B. napus, an allopolyploid, originated by hybridization between B. rapa and B. oleracea only ~ 7500 years ago [19]. Therefore, the A. thaliana gene should have 3 corresponding B. oleracea and B. rapa genes and have 6 B. napus genes if no gene was lost. However, there is a high possibility of gene loss after WGD events. For all 7 A. thaliana BES1 genes except Ath-BES1, the loss events occurred in B. rapa and B. oleracea (Fig. 5b). On inspection, B. napus BES1 genes were lost when comparing with A. thaliana genes. In fact, we thought the BES1 gene was not lost, because B. napus originated by hybridization of B. rapa and B. oleracea, and the loss occurred during the fusion of these two genomes.

BES1 gene expression pattern and network construction in B. napus and model species

The BR signalling pathway has been studied thoroughly at the genetic and molecular level in A. thaliana [52–54]. The studies showed that BZR1 and BES1 are important components of BR signal transduction [55, 56]. Plants with impaired BR production exhibit many growth defects, such as dwarfism, or organ expansion reduction [57, 58]. BES1 genes repress the expression of several BR biosynthesis enzymes, such as CPD and DWARF4 [59, 60]. Based on the microarray and ChIP-chip data, 1609 and 953 BR-regulated target genes have been identified for BES1 and BZR1, respectively [15, 61]. The construction of an expression detection or interaction network will aid in revealing the regulation of BES1 genes.

In this study, we conducted expression analyses of BES1 genes in B. napus and A. thaliana by using RNA-Seq and qRT-PCR datasets. In B. napus, most genes of the G1 and G4 groups showed higher expression in both roots and leaves. Interestingly, we found that not all duplicated genes were highly expressed. In the G1 group, there were 4 and 2 homologous genes with the A. thaliana BES1 gene in subgenome A and C, respectively. However, the Bna-BES1–013 (from subgenome A) and Bna-BES1–027 (from subgenome C) had a lower expression level than the other 4 genes in roots and leaves. Similarly, this phenomenon was also found under cold, heat, and salt treatments. The results indicated that some genes may be sub-, neo- or defunctionalized during the species’ evolution. Furthermore, we conducted interaction networks for B. napus and A. thaliana. The network was more complex for BES1, BZR1, and BEH1 than for other genes. This indicated that they may play a more important core role in the regulation network. Comparative analysis of the expression pattern and construction of the regulatory network will provide a very favourable support for the study of BES1 gene function in B. napus and other related species.

Exploring BES1 gene function in non-model species

The functions of most BES1 genes have been well characterized in A. thaliana. BES1 targets are not only auxin responsive genes, but are also auxin efflux facilitators (PIN4, PIN7), which have profound effects on auxin action [15, 62]. Based on microarray and chromatin immune precipitation (ChIP), AtMYB30 was identified, which is a direct target gene of AtBES1 [63]. By spectrometry identification and genetic analysis, it was found that MAX2 mediates the ubiquitination and degradation of BES1 protein [64]. In addition, the BES1 gene is a direct substrate for MPK6 to regulate the immune response of plants [65]. BZR1 mediates a trade-off between plant innate immunity and growth [66]. Therefore, a comparison of sequence homologs between model and non-model species might aid in understanding the function of these BES1 genes in non-model species. Taking the Brassicaceae species as an example, we checked genes within the same taxonomic group on the phylogenetic tree, which could have similar functions (Fig. 5b).

We identified 3 BES1 genes (Bra-BES1–010, Bra-BES1–013, Bra-BES1–014) in B. rapa, 3 BES1 genes (Bol-BES1–006, Bol-BES1–012, Bol-BES1–013) in B. oleracea, and 6 BES1 genes in B. napus, which clustered together with the BES1 gene of A. thaliana (Fig. 5b), functionally related to cooperating with transcription factors to regulate BR-induced genes [2, 3]. Similarly, several homologous genes in three Brassica species were clustered together with other BES1 family genes, such as BZR1, BEH1–4 (Fig. 5b), functionally involving BRs regulation [13, 55, 64–66]. These comprehensive and comparative analyses in B. napus and model species provides rich valuable resources for understanding the BES1 genes’ function and regulatory mechanisms in B. napus and other non-model species.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we comprehensively analysed the evolutionary pattern, gene synteny, gene duplication or losses, orthologous and paralogous genes, positive selection, and interaction networks of BES1 genes involved in the BRs pathway. A total of 132 BES1 genes were identified among 19 representative species. This effort can serve as a first step in comprehensive functional characterization of BES1 genes by reverse genetic approaches and molecular genetics research. This study provides useful resources for future studies on the structure and function of BES1 and for identifying and characterizing these genes in other species. In addition, this study may also facilitate our understanding of the effect of duplication or losses during the evolution of polyploidy.

Additional files

Figure S1. The positive selection analyses for each group of BES1 gene family in representative species. The ω on the clades is dn/ds value under M8 model of codeml, which indicates the positive selection nodes. (PDF 634 kb)

Figure S2. The sequences of motif 1 to motif 10 of BES1 gene family among examined species. Figure S3. The conversed motifs (M1 to M10) analyses for each group using the MEME program. Figure S4. The sequences alignment of F1, F2, and F3 subgroups among examined species. The Glyco_hydro_14 domain contained in F1 and F2 subgroups is marked using the blue dashed box in F3 subgroup. Figure S5. The analyses of Glyco_hydro_14 domain, including (a) protein structure, (b) alignment with the homology model (1fa2.1.A), (c) prediction of local similarity to target, (d) comparison with non-redundant set of PDB structures. Figure S6. The analyses of orthologous BES1 genes between O. sativa and other examined species. (a) The interaction network constructed using the orthologous gene pairs between O. sativa and other species. (b) The number of orthologous genes in each species with 6 O. sativa BES1 genes. Figure S7. The analyses of orthologous BES1 genes between A. trichopoda and other examined species. (a) The interaction network constructed using the orthologous gene pairs between A. trichopoda and other species. (b) The number of orthologous genes in each species with 4 A. trichopoda BES1 genes. Figure S8. The analyses of orthologous BES1 genes between S. moellendorffii and other examined species. (a) The interaction network constructed using the orthologous gene pairs between S. moellendorffii and other species. (b) The number of orthologous genes in each species with 4 S. moellendorffii BES1 genes. Figure S9. The analyses of orthologous BES1 genes between P. patens and other examined species. (a) The interaction network constructed using the orthologous gene pairs between P. patens and other species. (b) The number of orthologous genes in each species with 6 P. patens BES1 genes. Figure S10. The analyses of paralogous BES1 genes in each of the examined species. The green lines indicated the 4 B. napus BES1 genes, which had more than 1 paralogous genes. Figure S11. The reconstructed phylogenetic tree according to the duplication and losses of BES1 genes at different stages of plant evolution. Figure S12. The histogram of BES1 genes expression in root and leaf of B. napus. The genes marked with green located subgenome A, and red located subgenome C of B. napus. (PDF 4242 kb)

Table S1. The list of orthologous BES1 gene pairs between B. napus, A. thaliana, O. sativa, A. trichopoda, S. moellendorffii, P. patens and other examined species. Table S2. The list of paralogous BES1 gene pairs in each of other examined species. Table S3. The duplicated type of BES1 genes in B. napus and each representative species. Table S4. The comparative of synteny analyses for BES1 genes and all genes in B. napus and other representative species. Table S5. The domain and annotation of the BES1 genes and their target genes in A. thaliana network for comparative ananlysis with B. napus. Table S6. The nodes information and the assessment of the interaction network for BES1 genes in A. thaliana. Table S7. The enrichment ananlyses of the genes involved in the BES1 genes networks in A. thaliana for comparative ananlysis with B. napus. Table S8. The expression information of the BES1 genes in root and leaf for A. thaliana, and the gene expression was obtained from the BAR database. Table S9. The expression level of the BES1 genes in root and leaf for B. napus and A. thaliana. The gene expression was determined by the B. napus RNA-Seq data (RPKM) and the BAR database for A. thaliana. (XLS 159 kb)

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei (C2017209103), China-Hebei 100 Scholars Supporting Project to XW (E2013100003), and the Doctoral Scientific Research Foundation of North China University of Science and Technology to XS.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study were included in this published article and the Additional files.

Abbreviations

- BES1

BRI1-EMS-SUPPRESSOR1

- BIM1

BES1-interacting Myc-like1

- BRs

Brassinosteroids

- ChIP

Chromatin immune precipitation

- JTT model

Jones, Taylor and Thorton model

- LR tests

Likelihood ratio tests

- NLS

Nuclear localization signal

- WGD

Whole-genome duplication

Authors’ contributions

The study was conceived by X.W and X.S. X.S., X.M., T.W., J.C., J.H., D.G., J.W., L.W., W.G., S.F., M.L., Q.W., W.Z., T.R., and W.G. contributed to data collection and bioinformatics analysis. X.W., X.S., X.M., Q.H., Z.W., L.Z., and J.Z. participated in preparing and writing the manuscript. All authors contributed to revising the manuscript. All authors had read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12864-018-4744-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Xiaoming Song, Email: songxm@ncst.edu.cn.

Xiao Ma, Email: maxiaoxiaos@sina.com.

Chunjin Li, Email: 1396193464@qq.com.

Jingjing Hu, Email: 1076961427@qq.com.

Qihang Yang, Email: 1165031648@qq.com.

Tong Wang, Email: 1962434740@qq.com.

Li Wang, Email: wlsh219@126.com.

Jinpeng Wang, Email: wangjinpeng1010@vip.sina.com.

Di Guo, Email: msguodi@163.com.

Weina Ge, Email: gwn-06@163.com.

Zhenyi Wang, Email: zhenyiwang0301@163.com.

Miaomiao Li, Email: 3398166593@qq.com.

Qiumei Wang, Email: 2634235353@qq.com.

Tianzeng Ren, Email: 1398385536@qq.com.

Shuyan Feng, Email: 3437719462@qq.com.

Lixia Wang, Email: 1526795026@qq.com.

Weimeng Zhang, Email: 2256869483@qq.com.

Xiyin Wang, Email: wang.xiyin@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Glazebrook J. Genes controlling expression of defense responses in Arabidopsis--2001 status. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2001;4(4):301–308. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(00)00177-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yin Y, Vafeados D, Tao Y, Yoshida S, Asami T, Chory J. A new class of transcription factors mediates brassinosteroid-regulated gene expression in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2005;120(2):249–259. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yin Y, Wang ZY, Mora-Garcia S, Li J, Yoshida S, Asami T, Chory J. BES1 accumulates in the nucleus in response to brassinosteroids to regulate gene expression and promote stem elongation. Cell. 2002;109(2):181–191. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00721-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clouse SD. Molecular genetic studies confirm the role of brassinosteroids in plant growth and development. Plant J. 1996;10(1):1–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1996.10010001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li J, Chory J. Brassinosteroid actions in plants. J Exp Bot. 1999;50(50):275–282. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bajguz A, Hayat S. Effects of brassinosteroids on the plant responses to environmental stresses. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2009;47(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jin SH, Li XQ, Wang GG, Zhu XT. Brassinosteroids alleviate high-temperature injury in Ficus concinna seedlings via maintaining higher antioxidant defence and glyoxalase systems. AoB Plants. 2015;7:1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Vardhini BV, Anjum NA. Brassinosteroids make plant life easier under abiotic stresses mainly by modulating major components of antioxidant defense system. Front Environ Sci. 2015;2:1-16.

- 9.Oklestkova J, Rárová L, Kvasnica M, Strnad M. Brassinosteroids: synthesis and biological activities. Phytochem Rev. 2015;14(6):1053–1072. doi: 10.1007/s11101-015-9446-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walcher CL, Nemhauser JL. Bipartite promoter element required for auxin response. Plant Physiol. 2012;158(1):273–282. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.187559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nemhauser JL, Mockler TC, Chory J. Interdependency of brassinosteroid and auxin signaling in Arabidopsis. PLoS Biol. 2004;2(9):E258. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang ZY, Nakano T, Gendron J, He J, Chen M, Vafeados D, Yang Y, Fujioka S, Yoshida S, Asami T, et al. Nuclear-localized BZR1 mediates brassinosteroid-induced growth and feedback suppression of brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Dev Cell. 2002;2(4):505–513. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00153-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang J, Zhang C, Wang X. A recently evolved isoform of the transcription factor BES1 promotes brassinosteroid signaling and development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2015;27(2):361–374. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.133678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lachowiec J, Lemus T, Thomas JH, Murphy PJ, Nemhauser JL, Queitsch C. The protein chaperone HSP90 can facilitate the divergence of gene duplicates. Genetics. 2013;193(4):1269–1277. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.148098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu X, Li L, Zola J, Aluru M, Ye H, Foudree A, Guo H, Anderson S, Aluru S, Liu P, et al. A brassinosteroid transcriptional network revealed by genome-wide identification of BESI target genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2011;65(4):634–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Zhang YJ, Yang BJ, Yu XX, Wang D, Zu SH, Xue HW, Lin WH. Functional characterization of GmBZL2 (AtBZR1 like gene) reveals the conserved BR signaling regulation in Glycine max. Sci Rep. 2016;6:31134. doi: 10.1038/srep31134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu P, Song XM, Wang Z, Duan WK, Hu R, Wang WL, Li Y, Hou XL. Genome-wide analysis of the BES1 transcription factor family in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp pekinensis) Plant Growth Regul. 2016;80(3):291–301. doi: 10.1007/s10725-016-0166-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vert G, Nemhauser JL, Geldner N, Hong F, Chory J. Molecular mechanisms of steroid hormone signaling in plants. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:177–201. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.090704.151241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chalhoub B, Denoeud F, Liu S, Parkin IA, Tang H, Wang X, Chiquet J, Belcram H, Tong C, Samans B, et al. Plant genetics. Early allopolyploid evolution in the post-Neolithic Brassica napus oilseed genome. Science. 2014;345(6199):950–953. doi: 10.1126/science.1253435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawahara Y, de la Bastide M, Hamilton JP, Kanamori H, McCombie WR, Ouyang S, Schwartz DC, Tanaka T, Wu JZ, Zhou SG, et al. Improvement of the Oryza sativa Nipponbare reference genome using next generation sequence and optical map data. Rice. 2013;6(1):1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Cheng F, Liu S, Wu J, Fang L, Sun S, Liu B, Li P, Hua W, Wang X. BRAD, the genetics and genomics database for Brassica plants. BMC Plant Biol. 2011;11:136. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Albert VA, Barbazuk WB, de Pamphilis CW, Der JP, Leebens-Mack J, Ma H, Palmer JD, Rounsley S, Sankoff D, Schuster SC, et al. The Amborella genome and the evolution of flowering plants. Science. 2013;342(6165):1467-+. doi: 10.1126/science.1241089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodstein DM, Shu S, Howson R, Neupane R, Hayes RD, Fazo J, Mitros T, Dirks W, Hellsten U, Putnam N, et al. Phytozome: a comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D1178–D1186. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finn RD, Bateman A, Clements J, Coggill P, Eberhardt RY, Eddy SR, Heger A, Hetherington K, Holm L, Mistry J, et al. Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D222–D230. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Letunic I, Doerks T, Bork P. SMART 7: recent updates to the protein domain annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D302–D305. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marchler-Bauer A, Derbyshire MK, Gonzales NR, Lu S, Chitsaz F, Geer LY, Geer RC, He J, Gwadz M, Hurwitz DI, et al. CDD: NCBI's conserved domain database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D222–D226. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bailey TL, Boden M, Buske FA, Frith M, Grant CE, Clementi L, Ren J, Li WW, Noble WS. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Web Server issue):W202–W208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Biasini M, Bienert S, Waterhouse A, Arnold K, Studer G, Schmidt T, Kiefer F, Gallo Cassarino T, Bertoni M, Bordoli L, et al. SWISS-MODEL: modelling protein tertiary and quaternary structure using evolutionary information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Web Server issue):W252–W258. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winter D, Vinegar B, Nahal H, Ammar R, Wilson GV, Provart NJ. An "electronic fluorescent pictograph" browser for exploring and analyzing large-scale biological data sets. PLoS One. 2007;2(8):e718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jain M, Nijhawan A, Arora R, Agarwal P, Ray S, Sharma P, Kapoor S, Tyagi AK, Khurana JP. F-box proteins in rice. Genome-wide analysis, classification, temporal and spatial gene expression during panicle and seed development, and regulation by light and abiotic stress. Plant Physiol. 2007;143(4):1467–1483. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.091900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song X, Duan W, Huang Z, Liu G, Wu P, Liu T, Li Y, Hou X. Comprehensive analysis of the flowering genes in Chinese cabbage and examination of evolutionary pattern of CO-like genes in plant kingdom. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14631. doi: 10.1038/srep14631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song X, Liu G, Duan W, Liu T, Huang Z, Ren J, Li Y, Hou X. Genome-wide identification, classification and expression analysis of the heat shock transcription factor family in Chinese cabbage. Mol Gen Genomics. 2014;289(4):541–551. doi: 10.1007/s00438-014-0833-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinform. 2004;5:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Q, Zhang N, Zhang L, Ma H. Differential evolution of members of the rhomboid gene family with conservative and divergent patterns. New Phytol. 2015;206(1):368–380. doi: 10.1111/nph.13174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(12):2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ronquist F, Teslenko M, van der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, Hohna S, Larget B, Liu L, Suchard MA, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol. 2012;61(3):539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol. 2010;59(3):307–321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stolzer M, Lai H, Xu M, Sathaye D, Vernot B, Durand D. Inferring duplications, losses, transfers and incomplete lineage sorting with nonbinary species trees. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(18):i409–i415. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li L, Stoeckert CJ, Jr, Roos DS. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 2003;13(9):2178–2189. doi: 10.1101/gr.1224503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cline MS, Smoot M, Cerami E, Kuchinsky A, Landys N, Workman C, Christmas R, Avila-Campilo I, Creech M, Gross B, et al. Integration of biological networks and gene expression data using Cytoscape. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(10):2366–2382. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, Tang H, Debarry JD, Tan X, Li J, Wang X, Lee TH, Jin H, Marler B, Guo H, et al. MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(7):e49. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mondragon-Palomino M, Gaut BS. Gene conversion and the evolution of three leucine-rich repeat gene families in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22(12):2444–2456. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mondragon-Palomino M, Meyers BC, Michelmore RW, Gaut BS. Patterns of positive selection in the complete NBS-LRR gene family of Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome Res. 2002;12(9):1305–1315. doi: 10.1101/gr.159402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang Z. PAML: a program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Comput Appl Biosci. 1997;13(5):555–556. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/13.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang Z, Nielsen R, Goldman N, Pedersen AM. Codon-substitution models for heterogeneous selection pressure at amino acid sites. Genetics. 2000;155(1):431–449. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.1.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen K, Durand D, Farach-Colton M. NOTUNG: a program for dating gene duplications and optimizinggene family trees. J Comput Biol. 2000;7(3-4):429-47. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Cheng F, Wu J, Wang X. Genome triplication drove the diversification of Brassica plants. Horticult Res. 2014;1:14024. doi: 10.1038/hortres.2014.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Song X, Wang J, Ma X, Li Y, Lei T, Wang L, Ge W, Guo D, Wang Z, Li C, et al. Origination, expansion, evolutionary trajectory, and expression Bias of AP2/ERF superfamily in Brassica napus. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1186. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang X, Wang H, Wang J, Sun R, Wu J, Liu S, Bai Y, Mun JH, Bancroft I, Cheng F, et al. The genome of the mesopolyploid crop species Brassica rapa. Nat Genet. 2011;43(10):1035–1039. doi: 10.1038/ng.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu S, Liu Y, Yang X, Tong C, Edwards D, Parkin IA, Zhao M, Ma J, Yu J, Huang S, et al. The Brassica oleracea genome reveals the asymmetrical evolution of polyploid genomes. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3930. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parkin IA, Koh C, Tang H, Robinson SJ, Kagale S, Clarke WE, Town CD, Nixon J, Krishnakumar V, Bidwell SL, et al. Transcriptome and methylome profiling reveals relics of genome dominance in the mesopolyploid Brassica oleracea. Genome Biol. 2014;15(6):R77. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-6-r77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clouse SD, Sasse JM. BRASSINOSTEROIDS: essential regulators of plant growth and development. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1998;49:427–451. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Belkhadir Y, Wang X, Chory J. Arabidopsis brassinosteroid signaling pathway. Sci Signal. 2006(364):cm5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Wang ZY, Wang Q, Chong K, Wang F, Wang L, Bai M, Jia C. The brassinosteroid signal transduction pathway. Cell Res. 2006;16(5):427–434. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guo R, Qian H, Shen W, Liu L, Zhang M, Cai C, Zhao Y, Qiao J, Wang Q. BZR1 and BES1 participate in regulation of glucosinolate biosynthesis by brassinosteroids in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2013;64(8):2401–2412. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang C, Shang JX, Chen QX, Oses-Prieto JA, Bai MY, Yang Y, Yuan M, Zhang YL, Mu CC, Deng Z, et al. Identification of BZR1-interacting proteins as potential components of the brassinosteroid signaling pathway in Arabidopsis through tandem affinity purification. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12(12):3653–3665. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.029256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gasperini D, Greenland A, Hedden P, Dreos R, Harwood W, Griffiths S. Genetic and physiological analysis of Rht8 in bread wheat: an alternative source of semi-dwarfism with a reduced sensitivity to brassinosteroids. J Exp Bot. 2012;63(12):4419–4436. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Noguchi T, Fujioka S, Choe S, Takatsuto S, Yoshida S, Yuan H, Feldmann KA, Tax FE. Brassinosteroid-insensitive dwarf mutants of Arabidopsis accumulate brassinosteroids. Plant Physiol. 1999;121(3):743–752. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.3.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu H, Si J, Xu D, Lian G, Wang X. Heterologous expression of Populus euphratica CPD (PeCPD) can repair the phenotype abnormity caused by inactivated AtCPD through restoring brassinosteroids biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Acta Physiol Plant. 2014;36(36):3123–3135. doi: 10.1007/s11738-014-1633-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sakamoto T, Matsuoka M. Characterization of CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENESIS AND DWARFISM homologs in Rice ( Oryza sativa L.) J Plant Growth Regul. 2006;25(3):245–251. doi: 10.1007/s00344-006-0041-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sun Y, Fan XY, Cao DM, Tang W, He K, Zhu JY, He JX, Bai MY, Zhu S, Oh E, et al. Integration of brassinosteroid signal transduction with the transcription network for plant growth regulation in Arabidopsis. Dev Cell. 2010;19(5):765–777. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Paponov IA, Teale WD, Trebar M, Blilou I, Palme K. The PIN auxin efflux facilitators: evolutionary and functional perspectives. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10(4):170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li L, Yu X, Addie T, Guo M, Shigeo Y, Tadao A, Joanne C, Yin Y. Arabidopsis MYB30 is direct target of BES1 and cooperates with BES1 to regulate brassinosteroid-induced gene expression. Plant J. 2009;58(2):275–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03778.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang Y, Sun S, Zhu W, Jia K, Yang H, Wang X. Strigolactone/MAX2-induced degradation of brassinosteroid transcriptional effector BES1 regulates shoot branching. Dev Cell. 2013;27(6):681–688. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kang S, Yang F, Li L, Chen H, Chen S, Zhang J. The Arabidopsis transcription factor Brassinosteroid insensitive1-ethyl methanesulfonate-suppressor1 is a direct substrate of mitogen-activated protein Kinase6 and regulates immunity. Plant Physiol. 2015;167(3):1076–1086. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.250985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lozano-Duran R, Macho AP, Boutrot F, Segonzac C, Somssich IE, Zipfel C. The transcriptional regulator BZR1 mediates trade-off between plant innate immunity and growth. elife. 2013;2:e00983. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. The positive selection analyses for each group of BES1 gene family in representative species. The ω on the clades is dn/ds value under M8 model of codeml, which indicates the positive selection nodes. (PDF 634 kb)

Figure S2. The sequences of motif 1 to motif 10 of BES1 gene family among examined species. Figure S3. The conversed motifs (M1 to M10) analyses for each group using the MEME program. Figure S4. The sequences alignment of F1, F2, and F3 subgroups among examined species. The Glyco_hydro_14 domain contained in F1 and F2 subgroups is marked using the blue dashed box in F3 subgroup. Figure S5. The analyses of Glyco_hydro_14 domain, including (a) protein structure, (b) alignment with the homology model (1fa2.1.A), (c) prediction of local similarity to target, (d) comparison with non-redundant set of PDB structures. Figure S6. The analyses of orthologous BES1 genes between O. sativa and other examined species. (a) The interaction network constructed using the orthologous gene pairs between O. sativa and other species. (b) The number of orthologous genes in each species with 6 O. sativa BES1 genes. Figure S7. The analyses of orthologous BES1 genes between A. trichopoda and other examined species. (a) The interaction network constructed using the orthologous gene pairs between A. trichopoda and other species. (b) The number of orthologous genes in each species with 4 A. trichopoda BES1 genes. Figure S8. The analyses of orthologous BES1 genes between S. moellendorffii and other examined species. (a) The interaction network constructed using the orthologous gene pairs between S. moellendorffii and other species. (b) The number of orthologous genes in each species with 4 S. moellendorffii BES1 genes. Figure S9. The analyses of orthologous BES1 genes between P. patens and other examined species. (a) The interaction network constructed using the orthologous gene pairs between P. patens and other species. (b) The number of orthologous genes in each species with 6 P. patens BES1 genes. Figure S10. The analyses of paralogous BES1 genes in each of the examined species. The green lines indicated the 4 B. napus BES1 genes, which had more than 1 paralogous genes. Figure S11. The reconstructed phylogenetic tree according to the duplication and losses of BES1 genes at different stages of plant evolution. Figure S12. The histogram of BES1 genes expression in root and leaf of B. napus. The genes marked with green located subgenome A, and red located subgenome C of B. napus. (PDF 4242 kb)

Table S1. The list of orthologous BES1 gene pairs between B. napus, A. thaliana, O. sativa, A. trichopoda, S. moellendorffii, P. patens and other examined species. Table S2. The list of paralogous BES1 gene pairs in each of other examined species. Table S3. The duplicated type of BES1 genes in B. napus and each representative species. Table S4. The comparative of synteny analyses for BES1 genes and all genes in B. napus and other representative species. Table S5. The domain and annotation of the BES1 genes and their target genes in A. thaliana network for comparative ananlysis with B. napus. Table S6. The nodes information and the assessment of the interaction network for BES1 genes in A. thaliana. Table S7. The enrichment ananlyses of the genes involved in the BES1 genes networks in A. thaliana for comparative ananlysis with B. napus. Table S8. The expression information of the BES1 genes in root and leaf for A. thaliana, and the gene expression was obtained from the BAR database. Table S9. The expression level of the BES1 genes in root and leaf for B. napus and A. thaliana. The gene expression was determined by the B. napus RNA-Seq data (RPKM) and the BAR database for A. thaliana. (XLS 159 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study were included in this published article and the Additional files.