Summary

Although many oral ulcers have similar clinical appearances, their etiologies can range from reactive to neoplastic to oral manifestations of dermatological diseases. In patients with an HIV infection, fungal diseases may cause ulceration in the oral cavity; however, there have been few studies of oral ulcerative lesions associated with Candida in patients without an HIV infection. Nevertheless, we encountered chronic oral ulcer associated with Candida among our frequent outpatients without an HIV infection. The present article reviews the causes of oral ulcers, focusing on Candida as a protractive factor for chronic oral ulcers, and it is recommended that Candida involvement be considered in diagnosis of a certain chronic oral ulcer, that remains of unknown origin even if some examinations have been performed.

Keywords: Oral candidiasis, Secondary candidiasis, Chronic oral ulcer, Candida-associated lesions

1. Introduction

Ulcerative lesions are commonly encountered in oral diseases. Although many oral ulcers have similar clinical appearances, their etiologies can vary from reactive to neoplastic. The principal causes of oral ulceration are trauma, recurrent aphthous stomatitis, microbial infections, mucocutaneous diseases, systemic disorders, squamous cell carcinoma and drug therapy [1]. Microbial infections that may cause oral ulceration include syphilis, tuberculosis, leprosy, actinomycosis, fungal diseases, and viral diseases [1], [2], [3], [4]. Although many studies have reported that fungal diseases can cause oral ulcers, there have been few reports of oral ulcers associated with Candida. Munoz-Corcuera et al. and Porter and Leao reported that the most common mycosis of the oral cavity was candidiasis, which typically resulted in non-ulcerous lesions, but other mycoses such as histoplasmosis and aspergillosis may also cause oral ulcers in immunocompromised patients [4], [5]. Oral ulcers are a common complication in patients with an HIV infection; they occur in as many as 10–15% of these patients during the course of the infection. Although these ulcers represent an important cause of morbidity and may result from many different pathogens including viruses, bacteria, fungi, tumors, medications, and other causes, the prevalence of specific causes remains undefined [6]. Oral ulcers in patients with an HIV infection are not tumefactive and do not correspond to any recognized pattern of recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Although the clinical appearance is similar to minor or major aphthae, histological features are those of nonspecific ulcers, and cultures fail to identify a specific etiologic agent [6], [7], [8]. Oral lesions may be present at all stages of HIV infection, and may include oral ulcers, oral candidiasis, oral herpes, tonsillitis, gingivitis, and stomatitis. However, biopsies are not helpful in diagnosing ulceration in these patients, as a diagnosis can be made with a degree of certainly with a thorough history and examination [9].

These opinions are summarized as follows:

-

(i)

Etiologies of oral ulcers vary, and fungal infection is a cause.

-

(ii)

Fungi may cause oral ulcers in immunocompromised patients, but Candida does not cause oral ulcers.

Few studies have reported that Candida caused oral ulcers. However, we have reported chronic oral ulcers associated with Candida among frequent outpatients [10]. The present article reviews the causes of oral ulcers, focusing on Candida as a protractive factor for chronic oral ulcers.

2. Chronic oral ulcers

It is generally accepted that if the ulcer lasts for more than 2 weeks, it can be considered a chronic ulcer [4]. Acute ulcers with abrupt onset and short duration such as traumatic ulcers, recurrent aphthous stomatitis, Behçet’s disease, viral infections, allergic reactions, and others are excluded from this category.

Numerous systemic drugs have been implicated as causative agents of oral ulceration [11]. Drugs reported to induce oral ulcers include beta-blockers (labetalol), immunosuppressants (mycophenolate), anticholinergic bronchodilators (tiotropium), platelet aggregation inhibitors (clopidogrel), vasodilators (nicorandil), bisphosphonates (alendronate), protease inhibitors, antibiotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiretrovirals, antirheumatics, and antihypertensives (enalapril, captopril) [1], [4], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]. The underlying mechanism of drug-induced oral ulceration is often unclear [1].

Oral lichen planus is by far the most common dermatological disorder to cause oral ulcers [5]. The etiology of this disease has been related to a cytotoxic T cell-mediated attack on basal keratinocytes [18], [19]. However, the precise trigger for this immunological reaction is unknown. There is no evidence that clinical features of idiopathic oral lichen planus are any different from those of drug-induced diseases [20].

Pemphigus vulgaris and mucous membrane pemphigoid may result in chronic oral ulcers [4]. Pemphigus vulgaris is an immune-mediated chronic vesiculobullous mucocutaneous disease that almost invariably has oral features. Over half of the patients with pemphigus vulgaris have initial lesions in the oral mucosa [4].

Bacterial infections such as syphilis, tuberculosis, and actinomycosis may also cause oral ulcers [1], [2], [4], [5]. Aspergillus fumigatum may cause long-standing ulcers of the gingiva [21] or oral mucosa, as may Histoplasma capsulatum [22]. Systemic mycoses may cause oral ulcers, typically in immunosuppressed hosts [4], [5].

Eosinophilic ulcer of the oral mucosa is an uncommon self-limited oral condition that mostly appears on the tongue [23]. Its etiology is uncertain; however, the possibility that trauma may play a role in its development has often been postulated. It can remain for weeks or months and heals spontaneously [4]. Therefore, once malignancy is excluded by biopsy, the better approach is to wait and see. In many instances, no treatment is necessary [23].

3. Oral candidiasis

3.1. Candida-associated lesions of the mouth

Traditionally, classifications of oral candidiasis include acute pseudomembranous candidiasis (thrush), acute atrophic candidiasis, chronic hyperplastic candidiasis, and chronic atrophic candidiasis [24], [25]. It is now generally accepted that oral candidiasis can be divided into two broad categories: primary oral candidiasis and secondary oral candidiasis (Table 1) [26], [27]. Candidal infections confined to oral and perioral tissues are considered primary oral candidiasis, and disorders where oral candidiasis is a manifestation of generalized systematic candida infection are categorized as secondary [27], [29]. The primary oral candidasis are subdivided into three major variants: pseudomembranous, erythematous, and hyperplastic. In addition to these well-defined candidal lesions, a group of diseases have been termed “Candida-associated lesions” because their etiology is multifactorial and may or may not include candidal infection or infestation [27]. These include Candida-associated denture stomatitis, angular cheilitis, median rhomboid glossitis, and linear gingival erythema [27], [28]. However, in 2009 we reported chronic oral ulcers associated with Candida among frequent outpatients [10], and we have clinically encountered many additional identical cases since then. Therefore, we propose that this lesion should be included as a “Candida-associated lesion.” The details of chronic oral ulcers associated with Candida are described in the following section.

Table 1.

| Primary oral candidiasis | Secondary oral candidiasis |

|---|---|

| Acute forms Pseudomembranous Erythematous Chronic forms Hyperplastic Nodular Plaque-like Erythematous Candida-associated lesions Denture stomatitis Angular cheilitis Median rhomboid glossitis Linear gingival erythema |

Oral manifestations of systemic mucocutaneous candidiasis as a result of diseases such as athymic aplasia and candidiasis endocrinopathy syndrome |

3.2. Chronic oral ulcers associated with Candida (COUC)

We previously reported chronic oral ulcers associated with Candida [10]. The summary of the study is as follows. In patients with an HIV infection, fungal diseases may cause ulceration in the oral cavity; however, there have been few studies of oral ulcerative lesions associated with Candida in patients without an HIV infection. Six patients with chronic oral ulcers of unknown origin were included in the study; these patients were referred to our department after topical steroid therapy of the lesion was ineffective. Cases of traumatic ulcers and recurrent apthous stomatitis were excluded. Blood, histopathological, culture, and direct cytological examinations were performed. Histopathological examination revealed no specific findings other than inflammatory cellular infiltration with positive hematoxylin–eosin staining in all cases. Candida spp. were isolated in four cases with a culture test, and fungal pseudohyphae were detected in four cases by direct examination. All cases were treated successfully with anti-fungal agents.

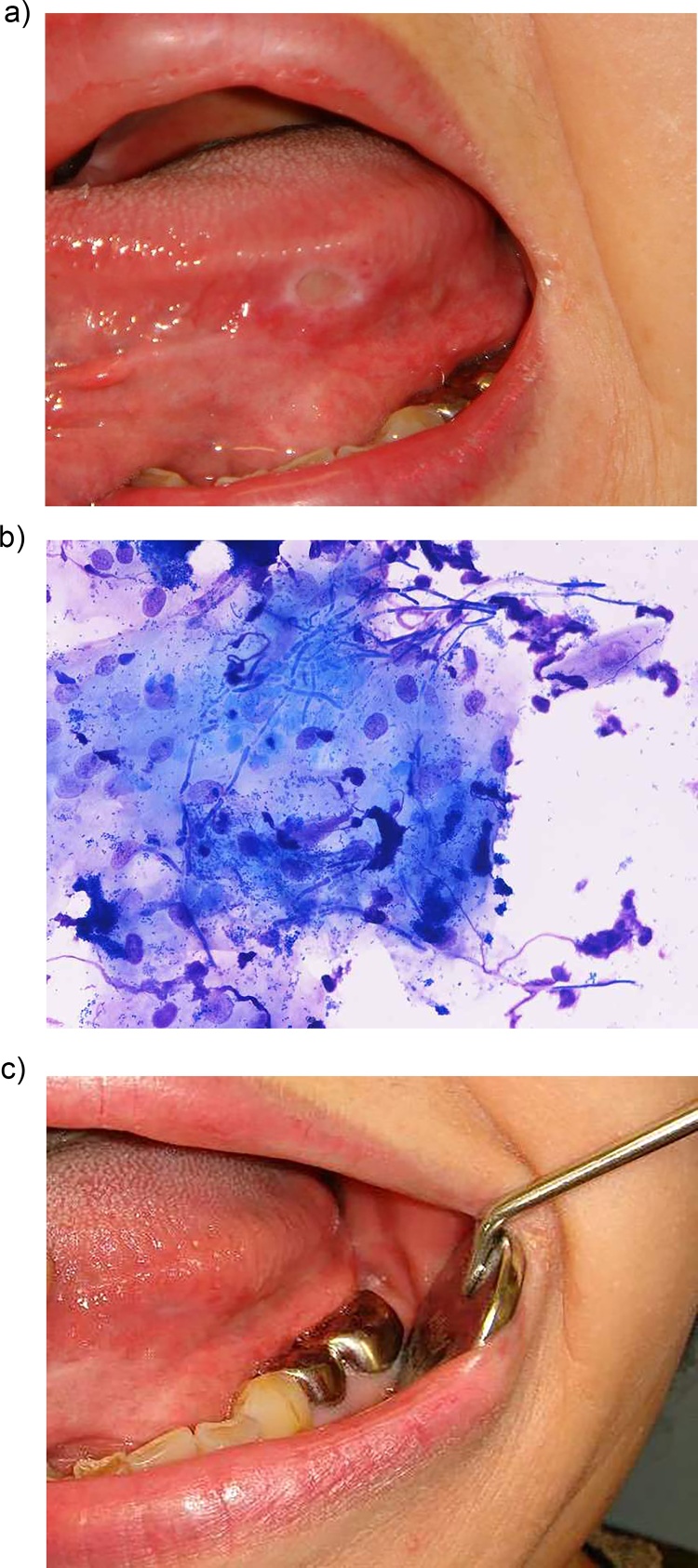

Although many oral ulcers have similar clinical appearances, their etiologies can range from reactive to neoplastic to oral manifestations of dermatological diseases. Diseases that induce erosive and ulcerative oral lesions should be considered in the differential diagnosis of chronic ulcers, including chronic ulcerative stomatitis, erosive lichen planus, pemphigus vulgaris, cicatricial pemphigoid, linear IgA bullous dermatosis, bullous lupus erythematosus, and desquamative gingivitis [30]. To diagnose COUC, we excluded these erosive and ulcerative lesions by histopathological and blood examinations. Neoplasm and viral infection were excluded on the basis of the clinical features and findings of histopathological and blood examinations. COUC presented with distinct clinical features and a usually single, nonindurated ulcer that showed no response to topical steroid and/or anti-traumatic therapy, persistent or chronic (Figs. 1, 2). Hence, COUC is different from recurrent apthous stomatitis, which recurs at intervals of a few days to up to 2–3 months and is usually treated with topical steroids. The clinical features of oral ulcers in our study can be summarized as follows: (i) the lesion had a sharply demarcated margin without induration, (ii) it was single and static despite the long disease duration, (iii) all the lesions had been clinically diagnosed as recurrent apthous stomatitis or traumatic ulcer, and (iv) histopathological examination with hematoxylin-eosin staining of biopsy specimens showed no specific findings.

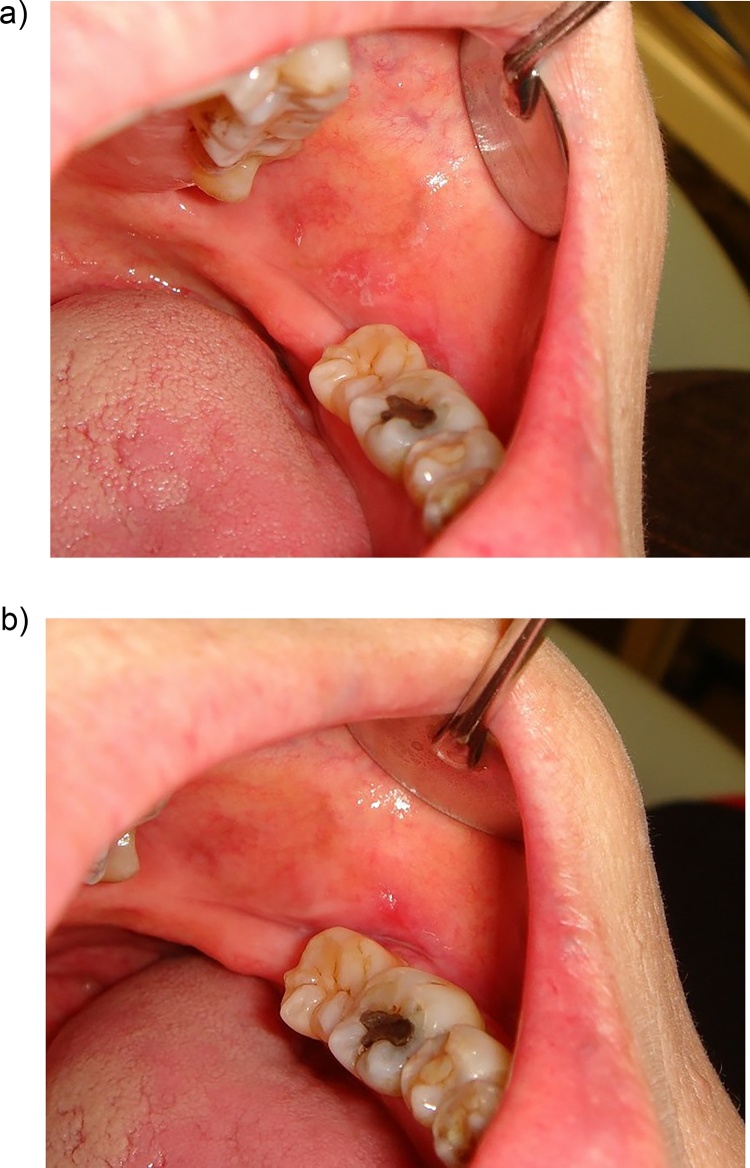

Figure 2.

Chronic oral ulcers associated with Candida (COUC) on the right border of the tongue. a: Tongue ulcer of a 2-month duration with complaint of tongue pain while eating. b: The ulcer disappeared after 2 weeks of anti-fungal treatment. However, results of cytological and mycological examinations were negative for candidiasis.

Figure 1.

Chronic oral ulcers associated with Candida (COUC) in the left border of the tongue. a: Tongue ulcer of a 3-month duration with complaint of tongue pain while eating. b: Fungal pseudohyphae revealed in the ulcer margin by quick cytological staining [10]. c: The ulcer disappeared after 2 weeks of anti-fungal treatment.

However, there have been few studies of oral ulcerative lesions associated with Candida other than studies of patients with an HIV infection [6], [8]. It has been reported that the most common mycoses in the oral cavity are candidasis, which typically cause non-ulcerous lesions [4], or Candida species, usually Candida albicans, which is the most common fungal infection of the mouth but rarely causes oral ulcers [5]. These are opposite opinions to our proposal. The cause of this difference may be the difficulty of detection of Candida in COUC. Approximately one third false-negative results were obtained when testing oral candidasis such as COUC and oral atrophic candidiasis, despite performing mycological, cytological, and histopathological examinations [10], [31]. However, favorable outcomes from anti-fungal treatment suggested that Candida was involved as an etiological agent in these lesions because the ulcers resolved dramatically with only anti-fungal treatment. Furthermore, we encountered COUC among our frequent outpatients without an HIV infection. The clinical features of this lesion and outcomes of anti-fungal treatment suggest that it should be included as a “Candida-associated lesion.”

3.3. Candida infection of the primary mucosal lesion (secondary candidiasis)

Occasionally, we encounter Candida infection such as oral lichen planus after topical steroid treatment of the primary oral mucosal lesion. These secondary candidasis have been reported in some patients with oral lichen planus being treated with steroids [32], [33]. Generally, Candida species have been identified in oral lichen planus lesions with or without topical steroid treatment. Culture studies have demonstrated Candida infection in 37%–50% of cases of oral lichen planus [34], [35], [36]. However, biopsy studies of lichen planus showed a lower frequency of Candida infection than culture studies. Holmstrup and Dabelsteen [37] reported that only one biopsy specimen had Candida invasion in the 43 biopsies of oral lichen planus lesions. Concurrent with the aforementioned findings, it is very difficult to identify Candida with a biopsy and/or direct examination of Candida-associated lesions.

In the classification of oral candidiasis, secondary candidiasis is usually accepted as an oral manifestation of systemic mucocutaneous candidiasis [27] or systemic candidiasis with secondary involvement of the oral cavity [28]. However, here, secondary candidiasis indicates Candida infection of the primary oral mucosal lesion with or without topical steroids.

Here we present cases treated in our clinic.

3.3.1. Candida infection with oral lichen planus

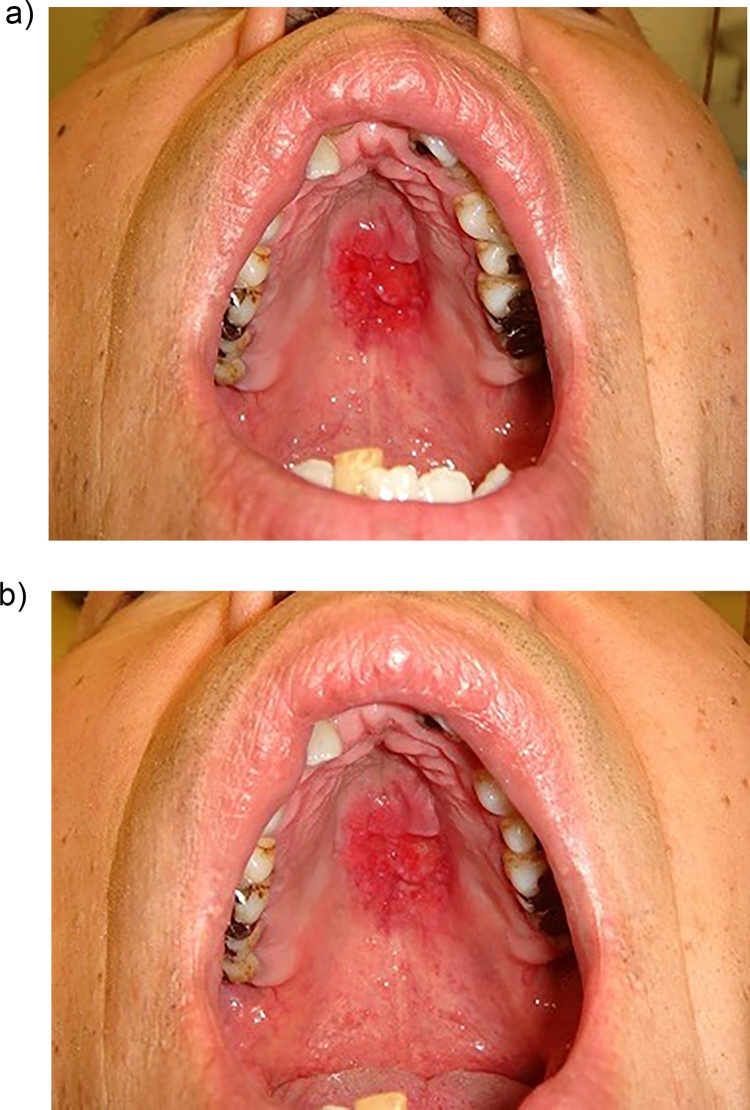

A 77-year-old woman was referred to our clinic with a 6-month history of slight pain in the left buccal mucosa. Physical examination revealed white patches with erosive areas (Fig. 3a). The result of a culture test revealed Candida albicans, and oral candidiasis was diagnosed. However, only partial improvement of the symptoms was seen after 3 weeks of anti-fungal treatment (Fig. 3b). We diagnosed a lichen planus candidal infection, and the lesion was treated successfully with additional topical steroids.

Figure 3.

Candida infection with the oral lichen planus. a: White lesion of the left buccal mucosa. b: Some remission was seen after 3 weeks of anti-fungal treatment.

3.3.2. Candida infection with the malignancy

A 55-year-old man was referred to our clinic with the chief complaint of pain in the palate. Physical examination revealed severe erosion of the mucous membranes of the hard palate (Fig. 4a). Direct examination and a culture test were positive for Candida albicans infection. However, improvement of the lesion was slight after three weeks of anti-fungal treatment (Fig. 4b). An adenocarcinoma was diagnosed by histopathological examination of a biopsy specimen.

Figure 4.

Candida infection with malignancy. a: Erosive lesion of the hard palate. b: Partial remission was seen after anti-fungal treatment for 3 weeks.

In addition, a case of Candida infection with drug-induced oral ulcer has been described elsewhere [17]. We believe that these are secondary candidasis of the primary lesion from the onset at first visit to our department. Therefore, the etiology of COUC may be one of secondary candidiasis of the primary mucosal lesion in the mouth. COUC might suggest prolonged disease duration owing to secondary candidiasis induced by primary treatment with topical steroids. It was unclear whether the primary lesion in COUC was trauma, recurrent apthous stomatitis, or another entity. However, it was suggested that Candida was involved as an etiological agent in COUC at the time of the first visit because the lesion resolved dramatically with only anti-fungal treatment and it regained a natural course of treatment only after control of the Candida infection was achieved.

4. Conclusions

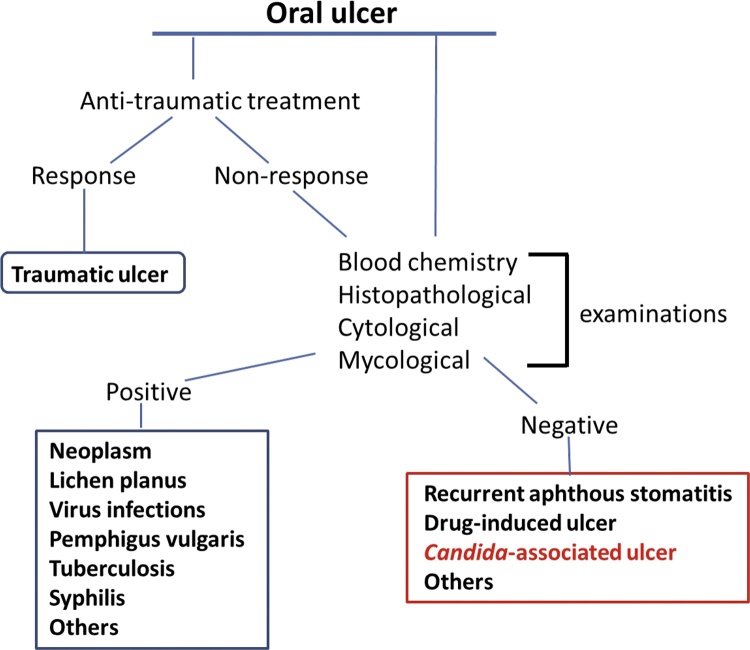

Generally, the diagnosis of oral candidiasis is based on clinical features and symptoms in conjunction with a thorough medical history. Provisional diagnoses are often confirmed through further histopathological and mycological examinations. A number of methods for the detection of Candida have been developed. Such methods include a swab, imprint culture, collection of whole saliva, oral rinse sample, and incisional biopsy [38]. Each sampling method has individual advantages and disadvantages, and the choice of technique is governed by the nature of the lesion to be investigated [39]. In pseudomembranous candidiasis, the presence of Candida hyphae can be confirmed with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining of a cytology smear of the pseudomembrane, allowing a quick and accurate diagnosis. However, in other oral candidal lesions, cytological smears usually fail to show any hyphal elements [39], [40]. We fully agree with this idea, because our previously reported cases highlighted the low detectable rate of Candida pseudohyphae by direct examinations and culture tests [10], [31]. Therefore, it is recommended that Candida involvement be considered in diagnosis of a certain chronic oral ulcer, that remains of unknown origin even if some examinations have been performed (Fig. 5). In drug-induced oral ulcers, histopathological examination usually reveals non-specific ulcer formation with marked infiltration of inflammatory cells [41]. Therefore, careful medical review of a patient’s medications is very important in such cases. When drug-induced oral ulcerations are suspected after careful clinical observation and review of medications, the prescribing doctor should be contacted to discuss the possibility of an alternative medication or a dose reduction [41]. When oral ulcers show typical clinical findings, differential diagnosis may be easy. However, the exact diagnosis is difficult in most cases. Although the most important principle for dealing with mucosal lesions in the mouth is constant observation for malignancy, clinicians should also consider Candida association in chronic and static lesions, even among frequent outpatients. Further COUC cases are required for further investigation.

Figure 5.

Diagnostic sequence of an oral ulcer.

Funding

There were no sources of funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Field E.A., Allan R.B. Review article: oral ulceration-aetiopathogenesis, clinical diagnosis and management in the gastrointestinal clinic. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:949–962. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reigezi J.A., Sciubba J.J. Oral Pathology — Clinical Pathologic Correlations. 3rd edition. WB Saunders; Philadelphia: 1999. Ulcerative conditions; pp. 30–82. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Munoz-Corcuera M., Esparza-Gomez G., Gonzalez-Moles M.A., Bascones-Martinez A. Oral ulcers: clinical aspects. A tool for dermatologist. Part I. Acute ulcers. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:289–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munoz-Corcuera M., Esparza-Gomez G., Gonzalez-Moles M.A., Bascones-Martinez A. Oral ulcers: clinical aspects. A tool for dermatologist. Part Ⅱ. Chronic ulcers. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:456–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porter S.R., Leao J.C. Review article: oral ulcers and its relevance to systemic disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:295–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ficarra G. Oral ulcers in HIV-infected patients: an update on epidemiology and diagnosis. Oral Dis. 1997;3(Suppl. 1):183–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1997.tb00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.EC-Clearinghouse on oral problems related to HIV-infection and WHO Collaborating Centre on oral manifestations of the immunodeficiency virus. J Oral Pathol Med. 1993;22:289–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piluso S., Ficarra G., Lucatorto M.F., Orsi A., Dionisio D., Stendardi L. Cause of oral ulcers in HIV-infected patients. A study of 19 patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1996;82:166–172. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(96)80220-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLean A.T., Wheeler E.K., Cameron S., Baker D. HIV and dentistry in Australia: clinical and legal issues impacting on dental care. Aust Dent J. 2012;57:256–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2012.01715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terai H., Shimahara M. Chronic oral ulcer associated with Candida. Mycoses. 2009;53:168–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Porter S.R., Scully C. Adverse drug reactions in the mouth. Clin Dermtol. 2000;18:525–532. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(00)00143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scully C., Bagan J.V. Adverse drug reactions in the orofacial region. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2004;15:221–239. doi: 10.1177/154411130401500405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naranjo J., Poniachik J., Cisco D., Contreras J., Oksenberg D., Valera J.M. Oral ulcers produced by mycophenolate mofetil in two liver transplant patients. Transpl Proc. 2007;39:612–614. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vucicevic Boras V., Savage N., Mohamad Zaini Z. Oral aphthous-like ulceration due to tiotropium bromide. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2007;12:E209–E210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adelola O.A., Ullah I., Fenton J.E. Clopidogrel induced oral ulceration. Ir Med J. 2005;98:282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boulinguez S., Sommet A., Bédane C., Viraben R., Bonnetblanc J.M. Oral nicorandilinduced lesions are not aphthous ulcers. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32:482–485. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2003.00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terai H., Shimahara M. Nicorandil-induced tongue ulceration with or without fungal infection. Odontology. 2012;100:100–103. doi: 10.1007/s10266-011-0015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramer M.A., Altchek A., Deligdisch L., Phelps R., Montazem A., Buonocore P.M. Lichen planus and the vulvovaginal-gingival syndrome. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1385–1393. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.9.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shichinohe R., Shibaki A., Nishie W., Tateisi Y., Shimizu H. Successful treatment of severe recalcitrant erosive oral lichen planus with topical tacrolimus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:66–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mccartan B.E., McCreary C.E. Oral lichenoid drug eruptions. Oral Dis. 1997;3:58–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1997.tb00013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myoken Y., Sugata T., Kyo T.I., Fujihara M. Pathological features of invasive oral aspergillosis in patients with hematologic malignancies. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;54:263–270. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(96)90737-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loh F.C., Yeo J.F., Tan W.C., Kumarasinghe G. Histoplasmosis presenting as hyperplastic gingival lesion. J Oral Pathol Med. 1989;18:533–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1989.tb01358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Segura S., Pujol R.M. Eosinophilic ulcer of the oral mucosa: a distinct entity or a non-specific reactive pattern. Oral Dis. 2008;14:287–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2008.01444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lehner T. Oral candidosis. Dent Pract. 1967;91:209–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lynch D.P. Oral candidiasis, history, classification, and clinical presentation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;78:189–193. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(94)90146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samaranayake L.P., Yaacob H.B. Oral candidosis. In: Samaranayake L.P., MacFarlane T.W., editors. Classification of oral candidosis. Wright; London: 1990. pp. 124–132. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samaranayake L.P., Leung W.K., Jin L. Oral mucosal fungal infections. Periodontol 2000. 2009;(49):39–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2008.00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharon V., Fazel N. Oral candidiasis and angular cheilitis. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:230–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2010.01320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Axell T., Samaranayake L.P., Reichart P.A., Olsen I. A proposal for reclassification of oral candidosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;84:111–112. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wörle B., Wollenberg A., Schaller M., Kunzelmann K.-H., Plewig G., Meurer M. Chronic ulcerative stomatitis. Br J Derm. 1997;137:262–265. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1997.18171898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Terai H., Shimahara M. Usefulness of culture test and direct examination for the diagnosis of oral atrophic candidiasis. Int J Derm. 2009;48:371–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.03925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vuckovic N., Bokor-Bratic M., Vuckovic D., Picuric I. Presence of Candida albicans in potentially malignant oral mucosal lesions. Arch Oncol. 2004;12:51–54. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luangjarmekorn L., Jainkittivong A. Topical steroid and antifungal agent in the treatment of oral lichen planus: report of two cases. J Dent Assoc Thai. 1986;36:9–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lundstrom I.M., Anneroth G.B., Holmberg K. Candida in patients with oral lichen planus. Int J Oral Surg. 1984;13:226–238. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(84)80008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krogh P., Holmstrup P., Thoron J.J., Vedtofte P., Pindborg J.J. Yeast species and biotypes associated with oral leukoplakia and lichen planus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;63:48–54. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(87)90339-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simon M., Jr., Hornstein O.P. Prevalence rate of Candida in the oral cavity of patients with oral lichenplanus. Arch Dermatol Res. 1980;267:318–328. doi: 10.1007/BF00403853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holmstrup P., Dabelsteen E. The frequency of Candida in oral lichen planus. Scand J Dent Res. 1974;82:584–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1974.tb01913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams D.W., Lewis M.A.O. Isolation and identification of Candida from the oral cavity. Oral Dis. 2000;6:3–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2000.tb00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farah C.S., Lynch N., McCullough M.J. Oral fungal infections: an update for the general practitioner. Aust Dent J. 2010;55(1 Suppl):48–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2010.01198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Farah C.S., Ashman R.B., Challacomber S.J. Oral candidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:553–562. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(00)00145-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jinbu Y., Demitsu T. Oral ulcerations due to drug medications. Jap Dent Sci Rev. 2014;50:40–46. [Google Scholar]